SETTING OUT AT DAWN

From the prow of a ship, Chinese tourists gaze out at the riotous greenery and jadeite water of a river gorge as traditional music plays and a tour guide recites a poem over a loudspeaker:

| 朝辭白帝彩雲間 |

At dawn depart Baidi midst many-colored clouds |

| 千里江陵一日還 |

Across 1,000 li to Jiangling in a single day return |

| 兩岸猿聲啼不住 |

From both banks the sound of gibbons crying without rest |

| 輕舟已過萬重山 |

The light skiff has already crossed myriad-fold mountains |

When the tour guide finishes her recitation, she praises the Three Gorges Dam project for “once again drawing the attention of the world” to this rugged stretch of river and mountains, as if to make up for a long lapse in interest. Meanwhile, a television on board the ship shows images of the Chinese leaders who first imagined and then finally built the dam—Sun Yat-sen, Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping—as well as footage of its early construction, which began in 1994. As the guide mentions the projected water level of the completed reservoir, a ship full of foreign tourists passes in the opposite direction.

These nested journeys through the landscape of the Three Gorges take place in Jia Zhangke’s 賈樟柯 Still Life (Sanxia haoren 三峽好人), a 2005 film set in the city of Fengjie as its low-lying neighborhoods were being demolished to make way for the Three Gorges Dam reservoir. If the images that Jia brings together in this sequence speak to the modern history of the Three Gorges as a site of national construction, then the four-line poem that echoes through it testifies to a much longer history of imagining and representing the region. Anthologized for over a millennium and still memorized by countless schoolchildren, “Setting Out at Dawn from Baidicheng 早發白帝城,” by the Tang Dynasty (618–907) poet Li Bai 李白 (701–762), is among the most famous depictions of the Three Gorges region.1 It charts a course from the fortified settlement that lies just west of the Gorges, through the towering mountains that separate the Sichuan Basin from the lakes and plains of eastern China, and on to the city of Jiangling in modern-day Hubei Province. Until recently, the Gorges, which extend for roughly 120 miles between Baidicheng in the west and the city of Yichang in the east, squeezed the Yangzi into a narrow, angry torrent, a string of treacherous rapids, boulders, reefs, shifting sandbars, and swirling currents. Before construction of the dam, the level of the river in the Gorges could rise seventy or eighty feet during major floods before spilling out over the countryside to the east, where it has killed countless millions over the centuries.2

In “Setting Out at Dawn from Baidicheng,” the mountains that form the Gorges and the surrounding terrain appear only at the very end of the last line, not as part of the scenery, but as territory “already crossed.” We sense their presence in the third line, but only from the cries of gibbons echoing across the river. That the Gorges remain a palpable presence despite their absence reminds us that we are dealing with a cultural landscape so iconic—so fixed in the imagination—that it can easily signify from the edges of the poem. Li Bai does not need to describe this landscape because his Tang readers know to follow the gibbons’ cries back in time to Li Daoyuan’s 酈道元 (d. 527) Commentary to the Classic of Rivers (Shuijing zhu 水經注), the source of many of the images and much of the language that was used to describe the Three Gorges region in subsequent centuries:

The two banks are chains of mountains with nary an opening. Layered cliffs and massed peaks hide the sky and cover the sun. If it is not midday or midnight the sun and moon are invisible. In summer, when the waters rise up the mountains, routes upstream and downstream become impassible. If there is a royal proclamation that must be spread quickly it sometimes happens that it departs Baidi at dawn and arrives at Jiangling at dusk, a distance of 1,200 li. Even if one were to ride a swift horse or mount the wind they could go no faster.

When winter turns to spring, there are frothing torrents, green pools, and crystalline eddies that toss and turn reflections. On the highest peaks strange cedars grow in profusion, hanging springs and waterfalls gushing from their midst. Pure, luminous, towering, lush—there is so very much to delight.

Whenever the weather clears or the day dawns with frost, within forests chill and by streams swift, one hears the long cries of gibbons high above. Unbroken and eerie, the sound echoes through the empty valleys, its mournfulness fading only after a long time. For this reason the fishermen [of the area] sing: “Of Badong’s Three Gorges, Wu Gorge is longest; when the gibbon thrice cries, tears drench your gown.”3

Li Bai’s allusions work because his readers already know the landscape as literary myth, but also because, his poem suggests, the physical landscape has not changed in the centuries since Li Daoyuan immortalized it.4 The same summer currents thunder through the gorges; the same gibbons cry mournfully into the chill of clear mornings.

For most of its history, the Three Gorges region has existed in the cultural imagination as a remarkably stable collection of images, ideas, and myths. Only recently, with the rise of tourism on the Yangzi, have large numbers of people from around China and the world been able to travel to the region. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, tourists flocked to the gorges and their cities to see them before the completion of the dam and its reservoir, which required the demolition of thirteen major cities and the relocation of upwards of 1.5 million people. Before the rise of mass tourism and the infrastructure and media that support it however, the Three Gorges were first and foremost a literary landscape—more imagined than visited.

For “Setting Out at Dawn from Baidicheng” to be recited in 2005, in the middle of the Gorges, with the dam nearing completion and its reservoir expanding, as though nothing had changed in nearly thirteen hundred years, demonstrates the enduring appeal of that landscape and the texts that shaped it. In reality, the tour guide’s use of the poem suggests a relationship between poetry and landscape very different from the one that made Li Bai’s original work possible. Its recitation in the place it describes establishes a connection between poem and landscape based less in the recognition of literary allusions than in the ability of tourists to retrace the poet’s journey in real time, even though that journey is mostly absent from his poem. Its appearance in Still Life, a film that captures the demolition of the modern city that now contains Baidicheng, forces us to confront the discrepancy between the air of timelessness that poems like “Setting Out at Dawn from Baidicheng” still lend the landscape and the radical changes the region has undergone in the last two decades. As much as the tourists might imagine themselves reenacting the poet’s journey, the historical footage that plays on the boat and the images of displacement that fill the film tell a different story. The moment the tour guide shifts from poem to dam and reservoir, she reminds us that the shoreline separating mountain from river in Li Bai’s poem will soon be submerged, just as the swift currents that he described will be slowed. Against touristic images of pristine nature, of the landscape of Li Bai protected and promoted as a world-class tourist destination, Still Life presents a landscape of spatial and social ruination.

⋆

Fixing Landscape maps the many points of connection between the seemingly timeless landscapes of the past and the spatial production of modern and contemporary China. We have become habituated to seeing the former as the sacrificial victim of the latter, but this book moves beyond simple narratives of loss to show how the recent reshaping of China as a modern nation-state is grounded not only in the political and economic transformations of the last few centuries, but also in the traditions that preceded them and against which they have so often signified. The story I tell here is not of a hitherto obscured cultural continuity, however, but of the shifting representational and spatial forms that have actively produced the Three Gorges as a famous landscape over the course of more than two millennia.

Though the Three Gorges Dam has already been built, its reservoir filled, and many residents of the region displaced, this remains an urgent story. As the scene of touristic wonder from Still Life shows, from certain angles the landscape of the Gorges looks unchanged. The level of the Yangzi has risen by close to six hundred feet, but the mountains that form the Gorges are more than three thousand feet high and the river still narrows dramatically when it enters the Qutang Gorge (Qutang xia 瞿塘峽) east of Fengjie. Even Baidicheng is still standing. No longer a promontory, it is now an island, its banks reinforced with concrete to protect them from the enormous water pressure of the reservoir. The Gorges have been flooded but not erased; they remain awe-inspiring. With the passage of time, this sense of awe will make it harder to remember what has been lost—not only the sights, sounds, and ecosystems of an undammed river and the fields, farms, homes, and relics of the people who occupied its banks, but also knowledge of the river as something enduring and changeable, a figure for and a site of history’s flux.

Fixing Landscape recovers the fluidity of the Three Gorges as a cultural concept and physical reality that has been shaped over time, inscribed and reinscribed to support shifting values. My approach is inspired in part by what Ann Laura Stoler calls “concept-work,” a critical method that rejects stability “as an a priori attribute of concepts.”5 By considering the Three Gorges as a concept that is “provisional, active, and subject to change,” we remain sensitive to its multiplicity and the frequency with which it has been reinscribed to bear new meanings that are, more often than not, grounded in myths of cultural stability.6 The stability of the Three Gorges as a cultural, geographical, and national landscape is an effect, a product of physical and representational processes that have homogenized and simplified the region. These processes have not only facilitated the region’s cooptation by the state, but also obscured how the poetic and pictorial landscapes of the past relate to both the Three Gorges Dam project and the contemporary works of art it has inspired. This book refuses to take the Three Gorges as a given—whether historical, cultural, or even geographical—so that we might better understand how landscape emerges from the interaction of the representational and the physical. To readers interested in technical histories of hydropower and state building in China, my approach may seem unorthodox, but I encourage them to read on and take a closer look at the cultural and aesthetic grounds of our material entanglements. Poems do not build dams, but this book shows that the Three Gorges Dam would not exist as we know it without them.

To do this, Fixing Landscape takes seriously the power that supports the Three Gorges Dam’s massive reorganization of space and the power of the landscape traditions that the region has inspired. By tradition, I have in mind neither the academically debunked but still popular vision of an unbroken lineage of cultural production based on a shared set of techniques, forms, or themes nor an “invented traditions” critique of that idea.7 Instead, I treat tradition the way a poet such as Li Bai treats his own poetry—as an iterative form that draws on the past but redefines it with each iteration. Holding on to tradition might seem to run counter to the concept of iterability (and hence to go against the Derridean grain), but it allows us to discuss the workings of borrowed language and shared images beyond the old oppositional discourse of tradition versus modernity.8 By focusing on tradition as a process of incremental reinvention that gains cultural potency by maintaining some resemblance to an imagined past, I hope to further bridge some of the many divides that separate the study of premodern, modern, and contemporary culture in the place that we now call China. The forms of representation I discuss here are part of a tradition not only because they draw on a shared cultural vocabulary, but also because they reinstantiate landscape in response to shifting historical conditions and forms of power.

To better understand how the Three Gorges has served as an important site for the creation and contestation of Chinese traditions, I have produced a book that ranges over more than two millennia and weaves premodern accounts of famous sites and figures together with modern and contemporary representations of the same places and people. Part I, which moves between the Tang, Song (960–1279), and Qing (1640–1911) dynasties and the present day, shows not only how the Three Gorges landscape was once defined by the fading and often ambiguous traces of historical and mythological figures but also how anxieties about the loss of those traces inspired attempts to “fix” them in and as landscape. Part II centers on the introduction of radically new ways of seeing, representing, and moving along the Yangzi in the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries. It was during this period that the Three Gorges were inscribed as a “Chinese landscape,” first through the cartographic imagination of Western travel writers, explorers, and amateur scientists and then through a nationalist discourse of modernization. Part III centers on contemporary filmmakers and visual artists who documented the transformation of the Three Gorges region in the lead-up to completion of the dam. These artists responded to the nationalist embrace of a development scheme that began as an imperialist project of mapping and penetrating the Chinese interior by reaching back to the premodern traditions that I describe in Part I.

The three parts of this book explore the complex and often elusive relationship between the art and science of landscape and the acts of landscaping that have indelibly shaped the Three Gorges region. Though they unfold chronologically, they do not tell a linear story. Each chapter is a microcosm of the project as a whole, a constellation of premodern, modern, and contemporary sources, and a melding of material and symbolic ways of engaging with landscape. Read in dialogue with one another, these diverse sources help us navigate the problems we face in confronting a landscape as richly overdetermined as the Three Gorges region is; they show us, for instance, how an eighth-century poem can change our understanding of a twenty-first-century film about a socialist experiment in spatial production developed in part by the American Bureau of Reclamation.

To further work against the pull of linear narratives, I have included a sequence of “passages” after parts I, II, and III that lead us back through Li Bai’s “Setting Out at Dawn from Baidicheng.” Like a recurring stratum in the sedimentary record of the landscape’s representational composition, this poem’s repetition as a quintessential expression of Chinese culture continues to lend the Three Gorges landscape an air of timelessness and stability. Its repetition in Fixing Landscape, however, is meant not only to destabilize conventional understandings of the entity that we call the Three Gorges, but also to inspire new ways of thinking about tradition as both concept and iterative practice. This is in some ways a methodological experiment, but I believe it is the method the topic demands. There are few places where the past and the present, the aesthetic and the material, have come together so intimately and violently as in the Three Gorges; this requires new ways of thinking and writing. My hope is that this approach will offer readers in both Chinese studies and neighboring fields new methods for rethinking spatial configurations across the globe with similarly storied cultural meanings. By bringing together genres and media normally segregated from one another, shifting between micro- and macro-temporal frames and intercutting historical moments, I have situated the dam project as an environmentally destructive and socially disruptive structure of “real-world” action and thought inextricably linked to the images and metaphors that constitute the Three Gorges as landscape. That the aesthetic may be an unacknowledged accomplice to material and political worlds is easy to claim, but harder to show; this book is, among other things, an illustration of this claim and a sourcebook for scholars working through similar problems in other real and representational worlds.

WHENCE THE THREE GORGES (DAM)?

A source of power for a flailing empire, a boon to the economy of the nation, a way of fixing the faults of nature—for a century, the Three Gorges Dam has been both a mirror and a cure for the anxieties of the men who imagined it. At 1.4 miles long, more than six hundred feet high, and with a reservoir that stretches four hundred miles, it exists in the realm of the mathematical sublime, a testament not only to China’s wealth and power, but also, as some would have it, to the spirit of its people (figures I.1–I.3). For those opposed to the project, it has appeared otherwise: as an environmental and social catastrophe, uprooting people, destroying cities and villages, and ravaging the ecosystems of the world’s third-longest river.9 The embodiment of the Chinese spirit stands against the erasure of local culture; the generation of hydropower against the sovereign power of the state; the aesthetics of the engineered against the beauty of a natural landscape. For most, the dam is a Manichean figure, black or white; reality, as always, is a grayer affair.

FIGURE I.1 The Three Gorges Dam in operation. See also color plate 1.

Source: iStock/Getty Images

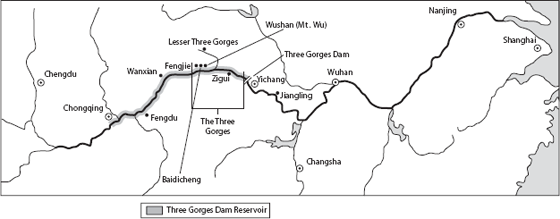

FIGURE I.2 Area affected by the Three Gorges Dam and its reservoir

This book does not weigh the benefits of the Three Gorges Dam against its costs. It treats the project first and foremost as a social, environmental, and cultural problem of massive proportions. The dam and its reservoir have indelibly inscribed the power of the state onto the surface of the earth. Its environmental and social consequences are still coming into view and will follow the Chinese people for centuries, if not millennia, to come. They constitute what Rob Nixon calls an “attritional catastrophe…marked above all by displacements—temporal, geographical, rhetorical, and technological displacements that simplify violence and underestimate, in advance and in retrospect, the human and environmental costs.”10 If, as Nixon argues, “such displacements smooth the way for amnesia, as places are rendered irretrievable to those who once inhabited them,” this book is an aide-memoire, but one that reconfigures how we see the present and reimagines how we might see the future by tracing the displacements of the Three Gorges Dam into the distant past and back again, into a strange new world just now forming, where memories of the past become haunting visions of the future.11

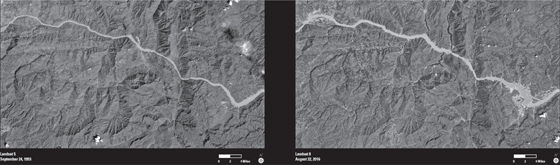

FIGURE I.3 Side-by-side satellite images from 1993 (left) and 2016 (right) show the extent of the Three Gorges Dam reservoir after completion of the dam.

Source: U.S. Geological Survey

While I am concerned with what the dam has done, and will address artistic responses to it in the final part of Fixing Landscape, one of my primary concerns is how it came to be, in both the short and (very) long term. How did this particular dam become the Three Gorges Dam? What does it mean to modify the word “dam” with the geographical designation “Three Gorges,” and how does the resulting name link an engineered structure to the rich cultural history of this region? I contend that rather than violently severing the links between aesthetic landscapes and physical lands, the dam reinforces them, even as it ends certain ways of seeing and moving through the Gorges. This is in no way an attempt to wash the dam in the healing waters of tradition—they are not necessarily salutary—but rather an effort to show not only how a geological formation along the Yangzi River became the Three Gorges, but also how the Three Gorges themselves became both a national “Chinese landscape” and a locus of “Chinese traditions.” These are neither unidirectional nor completed processes. Attending to the multiplicity of the Three Gorges as landscape and concept raises fundamental questions about how to define the traditional in contemporary China, a pressing task when both the political establishment and independent artists are appropriating Chinese traditions to promote radically different interests.

If the Three Gorges are especially attractive as a site of political inscription and artistic expression, it is due in part to the mysterious qualities long associated with the region. Depictions of the Gorges in literature, painting, and film abound with supernatural figures, clouds and rains that coalesce into beautiful goddesses, howling gibbons, and wildly changeable currents. In early geographical texts, writers even argued about where the Gorges began and ended and which sections of the river should be counted among the three.12 When the Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu 杜甫 (702–772), who is central to the story I tell in chapters 1 and 2, confronts the towering mountains that form Kuimen 夔門, the western gate of the Gorges, he invokes these debates by posing and immediately answering a rhetorical question:

| 三峽傳何處 |

The Three Gorges—from where do they come down to us? |

| 雙崖壯此門 |

Paired palisades secure this gate13 |

According to a widely repeated gloss, Du Fu is toying with his readers by invoking old textual debates to ask, “Where, according to tradition, are the Three Gorges?”14 The third character in the opening line, chuan 傳, generally refers to the transmission of scholarly learning, moral precepts, modes of governance, and esoteric practices rather than the continuity of a physically extended landmark. It is only by bracketing this interpretation and opting for an unconventional translation of the poem’s first line, however, that we can account for the spatial logic generated by the couplet’s parallelism. While Du Fu is certainly alluding to competing textual traditions, the argument for translating chuan as “according to tradition” is undermined by the transitive verb zhuang 壯 (to strengthen or secure something), which appears in the same position in the second line. As the title of the poem—“The Two Palisades of Qutang 瞿塘兩崖”—reminds us, it is the cliffs of Kuimen that secure the gorges, just as it is the Three Gorges that “come down” or “issue” from this specific spot.

The strangeness of Du Fu’s use of chuan is easily smoothed over by translation and our reliance on explanatory commentaries. To disregard it, however, is to miss an all-too-fleeting opportunity for exploring how the textual frames the physical. In both the second line of the first couplet and the next couplet, the textual ambiguities to which Du Fu alludes are already gone, overridden by the disorienting monumentality of Kuimen:

| 入天猶石色 |

Entering the sky—still the color of stone |

| 穿水忽雲根 |

Piercing the river—suddenly the roots of clouds |

That traditions of classifying this imposing landscape clashed must have seemed strange to Du. Formed by towering mountains on either side of the Yangzi just east of modern Fengjie, the gatelike Kuimen channels the river’s surging waters into the narrow confines of the gorges, beyond which they enter the network of lakes and channels that make up the middle and lower Yangzi before flowing into the East China Sea near modern-day Shanghai. As entry to the Three Gorges, Kuimen marks the treacherous boundary separating the riches of Sichuan—the “Land of Heaven’s Storehouse” (Tianfu zhi guo 天府之國)—from eastern China and the world beyond.

Despite the grandeur of the landscape that Kuimen opens onto, tourists who travel along the Yangzi today may still find themselves living out the ambiguous grammar of Du Fu’s lines, confused about where the Three Gorges end and begin. The Three Gorges—Qutang, Wu (Wu xia 巫峽), and Xiling (Xiling xia 西陵峽)—are in fact made up of multiple subgorges, each with its own evocative name—Bellows Gorge (Fengxiang xia 風箱峽), Military Texts and Precious Sword Gorge (Bingshu baojian xia 兵書寶劍峽), Ox Liver and Horse Lung Gorge (Niugan mafei xia 牛肝馬肺峽), to name a few. Along a tributary that feeds into the Yangzi at Wushan one even finds Three Little Gorges (Xiao sanxia 小三峽), once famous for their crystalline waters, now made murky by the reservoir. In Du Fu’s time, as now, the neatness of the Three Gorges designation and the seeming solidity of its mountains belie a murkiness on the ground that distracts us from changes—small and great—not only in how the meaning and power of the landscape have been inscribed, transmitted, and contested over millennia, but in how the physical landscape has been altered to suit human needs. The neatness of the Three Gorges designation is the product of a process that rejects the spatial, cultural, and even ethnic messiness of the past for the political and touristic expedients of the present.

Fixing Landscape recovers some of that messiness by paraphrasing Du Fu’s question: whence the Three Gorges? It treats the Gorges not as a uniform figure moving ineluctably toward the status of national landscape, but as a surface open to the inscription of personal and political desires and a constantly shifting concept that simultaneously attracts and repels attempts to “fix” it. To fix the landscape is not only to unify its heterogeneous qualities or to preserve and stabilize historical sites, but also to try to improve the Yangzi as a source of power and a route for travel and trade by blocking it behind a wall of concrete and steel. In recounting how people have gone about trying to fix the landscape, this book also shows how the landscape has resisted being fixed, how it has maintained a wondrous multiplicity and changeability. In this I follow Du Fu, who characterized the area around Kuizhou 夔州, the city directly to the west of Kuimen, as having a “changeable nature,” a land of clouds, winds, rains, and mists, a landscape fragmented, obscured, but ultimately made new by its transformations:

| 江城含變態 |

This Yangzi city has a changeable nature |

| 一上一回新 |

Once I climbed, now I return, finding all made new15 |

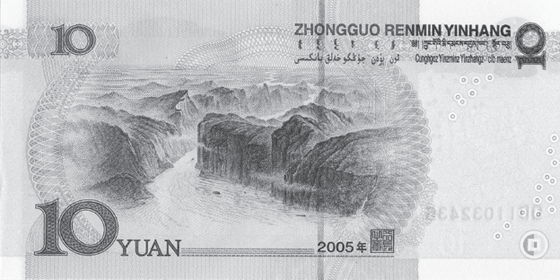

It is precisely this changeability that the myth of the Three Gorges as national landscape, indelibly fixed as an aerial vista on the back of the ten-yuan banknote (figure I.4), rejects.

FIGURE I.4 Ten-yuan note: looking east through Kuimen, with Baidicheng in the lower left and the Three Gorges extending into the distance. See also color plate 2.

ABOUT LANDSCAPE

In shaping this book on the Three Gorges as landscape, I have tried to synthesize methods and critical frames gleaned from geography, postcolonial studies, landscape studies, and art history with scholarship on premodern Chinese aesthetic traditions. If the former disciplines have provided a critical language for reframing landscape culture as a force for spatial production, the latter has offered a clear sense of the history of Chinese landscape as an aesthetic and ideological form. While I use the English term “landscape” for convenience in the chapters that follow, what I am talking about is really a hybrid concept—landscape/shanshui 山水—that encompasses not only premodern traditions centered on the Three Gorges and the modern landscaping of the region, but also the interaction of the two in the official discourse surrounding the dam and in artistic responses to it.

The literal meaning of the Chinese phrase shanshui 山水—is “mountains and water.” Before the seventh century, shanshui described the coexistence of these two elements rather than a generalized “landscape,” which is how the term is conventionally translated. In premodern poetry, shanshui operates as a spatial organizing principle for balanced depictions of the physical world and a symbolic method of conveying internal states, qualities, and religious beliefs. The phrase was adopted as a generic term for a category of painting only in the Tang Dynasty. In classical Chinese texts before and after the Tang, an aesthetically pleasing view is usually described in visual terms as a scene or prospect (jing 景), not a shanshui. In Chinese today, shanshui remains closely associated with pictorial or poetic landscapes done in a recognizably premodern style, while the modern word fengjing 風景 is used to refer to both physical and artistic landscapes produced in a Western style (e.g., fengjinghua 風景畫, or “landscape painting”).16

Though representations of the physical world appear in some of the earliest extant examples of Chinese painting, most scholars trace the rise of shanshui as an independent pictorial genre to the end of the Tang and beginning of the Song dynasties (early to mid-tenth century).17 Images of towering mountains, gnarled pines, and bucolic scenes of fishing villages and eremitic retreats evolved from earlier forms to support the new political and personal identities that defined the postaristocratic order of the Song.18 Rather than mere setting or backdrop, shanshui came not only to serve as a virtual site for religious and philosophical practices of self-cultivation, but also to promote the Neo-Confucian belief in the correspondence between the order of the physical and human realms.19 In images of mountains that embodied the ideal monarch and ancient pines that expressed the loyalty of literati, certain shanshui painters turned Confucius’s famous dictum—“The wise delight in waters, the benevolent delight in mountains 知者樂水, 仁者樂山”—into a model approaching pictorial allegory.20

Art historical and literary scholarship of the last two decades has radically reshaped our understanding of shanshui painting and poetry. Rather than simply an emblem of Chinese ideas about “nature”—a modern concept that was misleadingly translated using the ancient philosophical and cosmological term ziran 自然 beginning in the mid-nineteenth century—shanshui has come into view as a dynamic representational form.21 Martin Powers and Foong Ping have helped recover the ideological, political, and bureaucratic origins of shanshui painting in the Northern Song Dynasty, while Lothar Ledderose has offered a provocative theory of landscape’s origins in early religious iconography.22 In literary studies, Paul Kroll and Stephen Owen have undermined the “nature” of medieval Chinese landscape poetry by showing how subjective experiences of the physical world were filtered through texts, producing what Kroll calls “lexical landscapes and textual mountains,” and Owen, “bookish landscapes.”23 More recently, Paula Varsano has offered an important corrective to Kroll’s and Owen’s influential work by drawing attention to how vision and direct experience remained central to landscape poetry despite its textual character.24

These and other scholars of Chinese poetry and painting have illuminated the symbolic power of landscape/shanshui and its relation to subjective experience. Yet their work has not always accounted for the innumerable ways that repeated actions and habits combine to form everyday landscapes or for the mechanisms by which landscape ideas come to act materially in the production of space.25 In the first case, landscape is a lived phenomenon, the gradual and shifting product of paths taken and fields hoed over years, decades, centuries. Scholars working in a range of disciplines have traced the genesis of such “vernacular landscapes” while also describing their frequent cooptation or destruction by powerful political and economic forces.26 Throughout this book, I pay careful attention to the often violent relationship between vernacular and official landscapes. In the second case, which is of special concern here, landscape is more than a symbolic mode or a mirror of the natural world; it is also a cultural practice that actively changes the physical world—landscape is also a verb. When W. J. T. Mitchell first made this claim in his 1994 book Landscape and Power, he drew implicitly on ideas about space that had been percolating for decades in Marxist and Foucauldian approaches to geography.27 Scholars building on the work of Foucault, Henri Lefebvre, and Edward Soja have focused mostly on urban space or questions of regional and global uneven development under capitalism and imperialism, but their insistence on linking the social, representational, and spatial together offers an important starting point for my approach to landscape over the course of this book.28

In Part II of Fixing Landscape, I combine methods of spatial analysis borrowed from landscape studies, critical geography, and postcolonial studies in order to reframe the contemporary spatial reorganization of the Yangzi in terms of China’s colonial and imperial histories. I argue that the introduction of various spatial and representational technologies—from photography and mapmaking to travel writing and tourism—that supported the “opening” of the Chinese interior in the second half of the nineteenth century marked the proximate, if not ultimate, horizon of possibility for the Three Gorges Dam project. By textually and visually fixing the volatile Yangzi according to the standards of modern science and geopolitics, these technologies made it possible to reconceptualize the river as a stable geographical entity and, eventually, a natural resource that could be harnessed to produce energy. Anti-imperialist motivations notwithstanding, the development of the Yangzi by the Republican and Communist governments continues and in many ways perfects a partial and abortive attempt by foreign powers to master Chinese territory and resources.

Aspects of this part of my story will sound familiar to students of imperial knowledge production in other parts of the world. Landscape representation, geography, and cartography have been understood for decades as ways of seeing the world as intimately bound up with the extractionist and expansionist ideologies of capitalism and imperialism.29 I treat these spatial technologies as offering not just visual prospects, but also material ones that are actively produced as objects of exploitation. Although China was never fully colonized, the workings of imperial technology and discourse remained fully operable in China. It is, as Rey Chow wrote more than twenty years ago, “in spite of and perhaps because of the fact that [China] remained ‘territorially independent,’ [that] it offers even better illustrations of how imperialism works—i.e., how imperialism as ideological domination succeeds best without physical coercion, without actually capturing the body and the land.”30 There is, of course, more than one way to “actually” capture the land, just as there is more than one type of imperialism. The construction of China in the imperial imagination has had significant material effects that do not necessarily fit within the normal sequence of colonial conquest, expansion, and decolonization. What happened in Taiwan, Korea, and India or across the South American and African continents is different from what happened in China, but China was still an important site for perfecting imperial technologies and aesthetic forms.

Imperialism and colonialism in China are often understood in terms of “free trade,” the semicolonial occupation of treaty ports, or, in the case of Manchuria, settler colonialism. What makes the “opening” of the upper Yangzi so important to our understanding of how imperialism worked (and continues to work) in China is that it combined territorial and commercial interests with a nascent discourse of resource imperialism. European, Japanese, and American powers introduced ways of seeing the natural world as a source of extractable resources that could be captured as part of an imperial enterprise or kept under the control of a sovereign nation-state. In their struggle to establish China as a viable nation-state, both the Qing and Republican governments embraced forms of knowledge that made extractionist imperialism possible, even if they were never in a position to fully exploit the Yangzi.31 This form of imperialism lives on not only in the development of the Yangzi and other rivers in southwestern China (many of which flow into south and southeast Asia), projects that blur the line between national landscape and imperial prospect, but also in China’s global search for resources.32 For China to “see like a [modern] state” it first had to see like a modern imperial power.33 Keeping in view the “durability” of colonial and imperial dispositions, which reappear as so many “partial, distorted, and piecemeal” effects, allows us to look beyond the founding myths of the dam project as well as other narratives of origin and rupture that continue to segregate the “past” from the “present.”34

TRACE WORK

Fixing Landscape has been shaped by each of these rich approaches to the study of the representation, transformation, and exploitation of the earth. Perhaps its greatest influence, however, comes from two seemingly simple insights: First, the word “landscape” is an inherently ambiguous term that refers not only to a demarcated stretch of land that can be encompassed visually but also to the artistic framing and depiction of such a landscape. Second, our tendency to see these two landscapes as separate and stable concepts establishes a misleading hierarchy between the physical and the representational while obscuring the ambiguities that define their relationship. “Land” does not precede landscape; it is something already transformed, framed in visual and artistic terms, viewed from certain angles and not others, shaped by our experiences of other places and images. The physical land that appears at first glance as the raw material for artistic landscapes is always already artistic, particularly in culturally important places like the Three Gorges. To paraphrase Denis Cosgrove, we have inherited a way of seeing the world as landscape.35 This now-familiar conception of landscape was developed in the context of European and American culture; to make it productive in the story I tell here, I have refracted it through the social and historical lenses of shanshui while also triangulating these two concepts with a third figure—ji 跡 (also written 迹 and 蹟), or trace—which appears at the foundations of the Chinese tradition.

At its most basic, ji is a “footprint,” an impression on the earth that combines negative space and physical outline to show that someone has stepped in a particular spot. It is a mark of presence that signifies through absence; it is materially empty but culturally full. The footprint is depicted as a generative force in a number of early myths, including the Book of Odes’ (Shijing 詩經) account of the birth of Hou Ji 后稷, ancestor of the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) royal house, who was conceived when his mother “trod on the big toe of God’s [Di 帝] footprint.”36 Footprints also figure at the mythological origin of the Chinese writing system, which was supposedly modeled by the ancient sage Cang Jie 倉頡 on the tracks of birds (niaoji 鳥跡).37 These marks are not simply footprints, but also accidental textual inscriptions—the very first—a prelinguistic script that inspired the invention of the Chinese writing system. In both cases, the trace of the foot produces cultural narratives and forms that are themselves productive, whether of imperial legitimacy or textual tradition.

Ranging from the monumental to the microscopic, the traces that follow these mythical footprints are fundamentally paradoxical, simultaneously full (shi 實) and empty (xu 虛), present (you 有) and absent (wu 無). They index the moment and place of their creation and the presence of their creators, but only through the absence of the creator and the passage of time. They materialize the passage of time through decay, gaining in historical power and symbolic presence as they fade; even after they are totally effaced, they linger in the form of surrogate traces (marks adjacent to or commemorating the original trace). As an historically and culturally important landscape, it is inevitable that the Three Gorges region should be considered a palimpsest of such traces. But it is also a single, monumental trace: According to Chinese mythology, the Yangzi, along with all the rivers of China, were dug out by the deity turned founding emperor of the Xia Dynasty (the first dynasty in Chinese history), Yu the Great 大禹, sometime in the late third millennium BCE. For millennia, the Gorges have been described in poetry and prose as traces of Yu’s dredging: “As for the Gorges of eastern Ba, they were dredged and bored by the Lord of Xia. Sheer cliffs that soar 10,000 zhang high, like a wall they stand, streaked and striated.”38

In this book, landscape/shanshui is a way of seeing the world as a site of inscription constituted by innumerable ji/traces and acts of tracing, whether historical (landmarks, ruins, monuments) or aesthetic (poems, travelogues, paintings), which stand always in the shadow of the “traces of Yu” (Yuji 禹跡). This approach resonates with Paul Carter’s notion of “dark writing,” the traces of human movements that are so often erased from contemporary renderings of the world, but that constitute “the way in which we figure forth the places we inhabit.”39 To follow traces in a place like the Three Gorges is to “figure forth” the landscape by participating in an endless retracing, covering the same territory that others have covered, and thus touching a range of pasts that extend far beyond those that immediately precede you. Reading the world through the dark writing of these traces allows one “to associate formerly distant things on the basis of some imagined likeness…[and] to draw together things formerly remote from one another.”40 It is the capacity of the trace to “draw together things” that makes it possible to write this book not as a strictly linear history of representations of the Three Gorges, but as a juxtapositional account of landscape as the product of overlapping and intersecting traces and acts of trace making.41

TRACING THE TECHNO-POETIC LANDSCAPE

Written in the long shadow cast by the completed Three Gorges Dam, Fixing Landscape might appear elegiac—a lament for what once was and could have been—but this is not a work of mourning. I believe that the people and environments of the Three Gorges deserve our anger over the destruction caused by the dam, but the landscape traditions centered there have not died. If anything, they have grown stronger, richer, and stranger in the face of change. What we are witnessing in the artistic responses to the dam project that I describe in chapters 5 and 6 is not an ending, but rather the beginning of new ways of seeing and being in the world, indebted to the past but looking forward to an uncertain future.42 What will become of these new ways of seeing and being is hard to predict. If the past is any guide, they will confront, but also conceivably feed, the powers that brought them into being. Landscape aesthetics are not necessarily benevolent. As a constellation of ideas “embedded in social practices,” the culture of landscape can become a powerful “material force” for historical change, both good and bad.43 One of the arguments of this book is that poetry, film, painting, cartography, travel writing, photography, and other forms of landscape are not simply representational modes but material forces for spatial change. This claim has a structure that will sound familiar to postmodern ears, but one that has also been easier to repeat than to substantiate. Here, through a series of deeply researched close readings of phase states in the transformed yet enduring cultural landscape of the Three Gorges, I show that such aesthetic forms have long perpetuated ideas that either contribute directly to environmental ruin or make effective action against threats to the environment more difficult.

The complex and often ambiguous interplay between literature and the environment has become the focus of serious scholarly interest, as, for example, in Patricia Yaeger’s focus on the “real world consequences” of literary tropes that “encourage humans to treat [the world] as an inexhaustible storehouse of goods”; Timothy Morton’s critique of nature writing as a form of phenomenological “eco-mimesis” ill-equipped to deal with the temporal and spatial scale of climate change; Amitav Ghosh’s suggestion that many of our most unsustainable desires have been “midwifed” by the modern novel; Karen Thornber’s theory of the “ecoambiguity” of East Asian literatures that have long been seen as emerging from cultures that are somehow closer to nature; and Ursula Heise’s study of the cultural frameworks and narratives that shape our understanding of animal endangerment and extinction.44 Indeed, these are only few examples of how aesthetic forms have been reconceived as more than responses to or reflections of their environments, but also as active cultural and material agents—with a variety of potential consequences, good and bad. To overstate the negative impact of aesthetic forms would be to risk an excessively paranoid form of reading, but to ignore the possibility that dams and poems have something in common, or more especially that the latter might help make the former possible, would be to disregard the material force of representation.

In seeking to better understand the connections between landscape and the exploitation of the physical world, I have heeded Yaeger’s call for an ecocritical method that fuses the poetic with the technological, a “techno-poetics” that begins by looking beyond the metaphors that shape our experience of the natural world to the material realities of our current environmental crises and ends by asking not only how those metaphors might blind us to our predicament but also how they have contributed to it. For Yaeger, this method is founded on two observations: first, our relationship with the world “is always-already technological”;45 and second, the world “is [now] more techno than” natural.46 A vision of the Yangzi River as an inexhaustible natural resource or an “organic machine” would not appear until the early twentieth century, but over the course of two millennia, artists and writers have produced an aesthetic landscape grounded in an alternative set of technological images, metaphors, and tropes.47 The Three Gorges that they created is not an unambiguously natural landscape but rather a space produced through Yu the Great’s superhuman feat of dredging and clearing as well as a powerfully symbolic landscape bearing traces of some of the most famous figures in the Chinese tradition.

The geology and hydrology of the upper Yangzi make the Three Gorges Dam possible, but the structure exists partly because these long-standing technological and cultural tropes have made the region so attractive as a site for the inscription of a technologically modern China. As we shall see, the early lore and literature of the region have been mined for imagery and used to establish a link between deepest antiquity and the technological glories of the present. With the completion of the dam, the Three Gorges region has become a techno-poetic landscape—the ultimate expression of a conception of landscape as an inscribable and trace-bearing surface combined with the modern view of the world as an inexhaustible natural resource.48 If the landscape has become definitively technological, however, then the Three Gorges Dam is more than a feat of engineering; it is also something poetic—a soaring “wall of stone erected across the western Jiang (xijiang shibi 西江石壁),” as Mao envisioned it in his verse.49 It is only by acknowledging the poetic force of the dam that we can fully account for both the cultural legacy of the space it so radically altered and the many new works of art it has inspired.

The poetic in techno-poetic refers to more than just poetry; it encompasses the act of making or bringing into being, the productive capacity of representation to do things in the real world. Here we enter the more ambiguous side of the story. In place of oversimplified timelines that trace the dam project from Sun Yat-sen to Mao Zedong to Jiang Zemin, or grandiose speeches that link it to the mythological past, I offer a reappraisal not only of the forms of representation that remade the region in the modern period, but also of the poems, paintings, and works of prose that helped make the landscape famous in the first place and the works of art that have been produced in response to the dam project. It might seem that premodern travelers have, to adapt the old environmentalist guideline for nature-seekers, written only poems and left only footprints, but in reality they have helped fuel a dynamic that opposes poetic conceptions of the region as changeable with a powerful desire to fix it as a cultural site. As we shall soon see, the prestige accorded a poet such as Du Fu, for example, inspired later figures to search for the sites from which he described Kuizhou’s transformations. When they found his traces fading or irretrievable, they simply reinscribed them by repairing or building them anew, despite the fact that Du Fu’s finest poetry on the Three Gorges draws its power from processes of decay and displacement. This is a modest example of how techno-poetic culture works, but it is an important reminder that although landscape poetry in premodern China is a complexly intertextual affair, it also deeply influences how people interact with the land. To see the world poetically is potentially to demand that it look more like the texts that have shaped our vision, whether those texts are poems from the mid-eighth century or engineering schematics from the 1940s.