![]()

The United States and the United Kingdom went into the second Persian Gulf War with three significant military advantages compared with the 1991 war. First, their own combat capability, particularly in the strike warfare arena, had improved substantially since the time of Operation Desert Storm. Both countries commanded unprecedented defense-suppression, all-weather precision attack, and battlespace awareness assets. Second, and more important, Iraq’s military posture was only a shadow of what it had been when a much larger allied coalition mobilized forces to liberate Kuwait in 1991. Third, the coalition’s air contribution to Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan in 2001 and 2002 had taught valuable lessons that would apply directly to facilitating CENTCOM’s air war against Iraq.

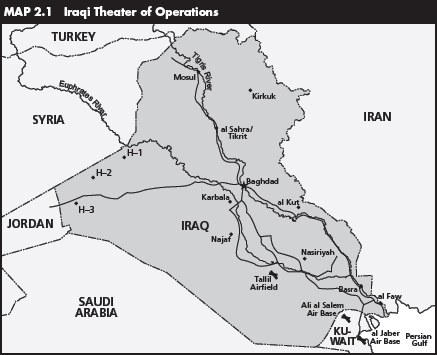

With respect to its land warfare potential, Iraq’s ground order of battle had declined from more than a million men under arms in January 1991 to only some 350,000 over the decade since Desert Storm. The regular Iraqi army had fallen in strength from 68 to 23 divisions, from 6,000 to 2,660 tanks, from 4,800 to 1,780 armored personnel carriers, and from 4,000 to about 2,700 rocket launchers and artillery pieces. The once-elite Republican Guard had been reduced from ten divisions to six, only four of which were heavy divisions equipped with T-72 tanks.1 That still, however, gave Iraq more than twice as many tanks and artillery pieces than the United States and the United Kingdom deployed for Iraqi Freedom (see map 2.1 for the disposition of those ground units on the eve of the campaign).

Iraq’s ground order of battle included 11 regular army divisions and 2 Republican Guard divisions positioned in the north, with 5 regular army divisions and the remaining Republican Guard and Special Republican Guard divisions concentrated around Baghdad. The Iraqi navy had just 2 or 3 warships remaining in service, and the number of still-operational Iraqi radar-guided SAM sites was down from 100 to only slightly more than 60, consisting of 14 MSA-2, 10 SA-2, 24 SA-3, and 15 SA-6 sites.2 Finally, Iraq’s air order of battle had declined from 820 to fewer than 300 fighter and attack aircraft, including 29 Mirage F1s, 14 MiG-29s, 12 MiG-25s, 44 MiG-23s, 98 MiG-21s, 28 Su-25s, 1 Su-24, and 51 Su-17/20/22s.3 Many of those aircraft, moreover, were thought to be unflyable because of an acute lack of periodic maintenance and spare parts. CENTCOM’s main concern with respect to the Iraqi air threat was the possibility that Iraqi UAVs carrying chemical or biological agents might be used against coalition troop concentrations as a desperation measure. The UN Security Council had limited the permissible range of Iraqi UAVs to only 150 kilometers; however, one Iraqi UAV type being flown off the backs of trucks was demonstrating a range capability of 500 kilometers. CENTCOM also had a related concern that unmanned Iraqi L-29 jet trainers might be pressed into service as drones for delivering chemical or biological weapons.

Source: Adaptation by Charles Grear based on CENTAF map

Prewar Defense-Suppression Moves

To prepare the expected battlespace in ways that would give the coalition the greatest possible starting advantage once Operation Iraqi Freedom was formally under way, CENTCOM undertook a number of measures well before the commencement of overt hostilities to diminish Iraq’s ability to resist the impending offensive. The most notable of these was a concentrated effort by CENTCOM’s air component to begin systematically degrading Iraq’s air defenses whenever and wherever opportunities to do so might present themselves.

During the briefing of the Generated Start option by Secretary Rumsfeld and General Franks to the president on February 7, 2002, a question had arisen concerning how CENTCOM might take advantage of Operation Southern Watch as a framework within which to increase the intensity of the bombing, with a view toward eliminating some critical Iraqi IADS nodes before the scheduled start of decisive combat operations.4 Over the course of the preceding 10 years, allied aircrews had flown nearly 200,000 armed overwatch sorties into Iraq’s northern and southern no-fly zones.5 They had been fired on by Iraqi air defenses numerous times, albeit with no loss of any aircraft over Iraq. That was a remarkable accomplishment, considering that the normal peacetime accident rate for that number of sorties would have occasioned as many as a dozen or more aircraft lost to in-flight mechanical failures or pilot error. Since January 2002 alone, CENTCOM had flown more than 4,000 sorties over southern Iraq, during which time Iraq’s IADS had targeted coalition aircraft at more than twice the rate registered throughout the preceding year.

Accordingly, on June 1, 2002, CENTAF initiated Operation Southern Focus, a determined effort to use Operation Southern Watch as a legitimate aegis under which to conduct intensified attacks against the Iraqi IADS in response to what General Moseley described as “more numerous and more threatening attacks” against allied combat aircraft patrolling the no-fly zones.6 Three months earlier, Moseley had laid the essential groundwork for this new undertaking by initiating a systematic transition from Southern Watch, which was geared toward maintaining the status quo in the southern no-fly zone, toward an operation aimed at “mapping the south” (i.e., cataloguing the Iraqi IADS in southern Iraq) through what he called “intrusive ISR.” That effort reflected his “desire to reseize the initiative and ensure air superiority in the southern no-fly zone and establish conditions for potential future operations to remove the Ba’athist Iraqi regime.” He also wanted to “expand targets beyond ‘self-defense’ solely against identified Iraqi ‘shooters’ to new target systems that also embraced Iraq’s IADS, regime command and control, and possible systems for the delivery of weapons of mass destruction.”7 What set this escalated concept of operations apart from the more straightforward tit-for-tat nature of Operation Southern Watch was the assumption by Southern Focus of the right to strike any IADS-related target in the southern no-fly zone in response to an Iraqi provocation, not merely the specific offending SAM or AAA site. An F-15E pilot, Capt. Randall Haskin, explained the logic: “This philosophy was basically that it was better to come back later with all of the appropriate assets on hand than it was to knee-jerk react to getting shot at and risk actually getting hit.”8

In connection with Operation Southern Watch, CENTAF had long maintained five graduated standing response options from which to choose when Iraqi air defenses fired on an allied aircraft. Counterattacks were mandatory and automatic in all cases, with the most forceful response option entailing concurrent or sequential attacks against multiple targets outside the no-fly zone. Such preplanned counterattacks required higher-level approval, in some cases from the president himself. Operation Desert Badger, to be executed in case an allied aircraft was downed by Iraqi fire, aimed at disrupting Iraq’s ability to capture the downed aircrew by attacking key command and control nodes in the heart of downtown Baghdad. Additional preplanned options were available in case an allied aircrew member was actually captured. Operation Desert Thunder was on tap in case of a Ba’athist assault against the Kurds in northern Iraq.9

Secretary Rumsfeld wielded an aggressive hand in seeking to bolster these anemic response options, which CENTCOM had inherited from the previous eight years of the Clinton administration. “Iraq’s repeated efforts to shoot down our aircraft weighed heavily on my mind,” he wrote in his memoirs. “ . . . I was concerned, as were the CENTCOM commander and the Joint Chiefs, that one of our aircraft would soon be shot down and its crew killed or captured. . . . The plan code-named Desert Badger was seriously limited. Its goal was to rescue the crew of a downed aircraft—but it had no component to inflict any damage or to send any kind of message to Saddam Hussein that such provocations were unacceptable.” Rumsfeld went on to recall: “Our friends in the region had criticized previous American responses to Iraqi aggression as weak and indecisive and had advised us that our enemies had taken comfort from America’s timidity. The Desert Badger plan was clear evidence of that problem. . . . If an aircraft was downed, I wanted to be sure we had ideas for the president that would enable him to inflict a memorable cost. The new proposals I ordered included attacks on Iraq’s air defense systems and their command and control facilities to enable us to cripple the regime’s abilities to attack our planes.”10

In a precursor to Operation Southern Focus, two dozen American and RAF aircraft had struck some twenty radar and command and control nodes throughout Iraq on February 16, 2001, some as close to the country’s heartland as the suburbs of Baghdad, in prompt response to intelligence reports that Iraq’s IADS was nearing a point of interconnecting some critical command and control sites with underground fiber-optic cables that were very difficult to locate. The intent of that attack, the most massive in two years, and conducted under the aegis of enforcing the southern no-fly zone, was to negate or at least hinder any such development before the installation could be completed.11 This effort by Hussein’s regime to enhance its IADS with a fiber-optic network was in part the result of an earlier loosening of economic sanctions against Iraq that had allowed French and Chinese commercial firms to provide Hussein with $133 million of telecommunications improvements, including fiber-optic cable installations and other digital enhancements to telecommunications that could be leveraged to increase the lethality of Iraq’s radar-guided SAMs.12

Indeed, well before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, CENTAF’s commander at the time, then Lt. Gen. Charles Wald, had fought to gain approval for more appropriate coalition responses to increasingly aggressive attempts by Iraq’s IADS to fire on coalition aircraft patrolling the no-fly zones in an apparent effort to shoot one down. With respect to his growing concern regarding the need for more forceful strike options, General Wald commented in an interview: “When I became the commander at CENTAF, I was not interested in just doing the status quo. My feeling was that we needed to do something different. . . . So we built a briefing and gave it to the CINC [commander in chief of CENTCOM] and the [Air Force] chief of staff, and in that briefing we recommended a change in how we did business—either we push it up, or we do the status quo, or we do hardly anything, we quit. We needed to get out of this middle road that was really dangerous . . . this cynical status quo approach to the no-fly zones and to Iraq. You can’t do this tit-for-tat thing. Our recommendation was that we do something more aggressive.”13 Rather than risk coalition aircraft in such small-scale retaliations, General Wald sought to establish restricted operating zones and gun-engagement zones that coalition aircraft were to avoid due to the concentration of Iraqi defenses, a measure that, in effect, ceded parts of the southern no-fly zone back to the Iraqis.

All of that changed dramatically with the onset in June 2002 of Operation Southern Focus, a substantially escalated initiative that allowed the coalition to reclaim the entire southern no-fly zone while at the same time drawing down Iraq’s command and control network in the southern half of the country by systematically going after enemy systems that allowed Iraq’s IADS to acquire and threaten coalition aircraft. Lt. Col. David Hathaway, General Moseley’s chief of strategy, explained how targets were chosen.

After I pitched the Southern Focus plan at CENTCOM, General Franks asked all the other component commanders for their proposed lists of desired Southern Focus targets. Both the land and maritime component commanders proposed targets in the vicinity of the Al Faw peninsula and the city of Basra, ranging from long-range artillery to Seersucker missile, naval command and control, and mine storage locations. Initially, those target nominations were deemed by CENTCOM to be insufficiently related to hostile Iraqi actions taken against coalition aircraft operating in the southern no-fly zone. It was not until the execution of OPLAN 1003V drew closer that such targets were considered and ultimately approved by General Franks.14

A pair of B-1s, for example, attacked and destroyed a Soviet-built P-15 Flat Face SAM acquisition radar near the H-3 airfield and an Italian-built Selena Pluto low-altitude surveillance radar near the Saudi and Jordanian borders.15

In a follow-up to this initiative, staff planners at CENTAF, in conjunction with those assigned to Joint Task Force Southwest Asia operating out of Saudi Arabia, generated an “RO-4” response option aimed at systematically taking down Iraq’s increasingly interconnected IADS by attacking the static surveillance radar and fiber-optic cable nodes inside the southern no-fly zone that had been providing enhanced early-warning information to Iraq’s southern air defenses. Iraq had directed AAA fire at allied aircraft at least fifty-one times since January 1, 2001, and had launched SAMs with hostile intent fourteen times. In light of this, General Franks, who had replaced Gen. Anthony Zinni as CENTCOM’s commander in chief in July 2000, approved sending the RO-4 option on to the Joint Staff for approval by the new civilian leadership of the recently inaugurated administration of President George W. Bush.16

A report of slightly more than one hundred Iraqi SAM launches against U.S. and RAF aircraft between February 16 and May 9, 2001, that were characterized as “an unusually determined effort to shoot down an [allied] aircraft” added incentive for the new administration to approve this ramped-up effort against Iraq’s air defenses.17 Furthermore, there had been a significant spike in recent incursions into the no-fly zones by Iraqi MiG-25 interceptors flying at speeds of up to Mach 2.4 at times when patrolling allied aircraft were either leaving the zones or were known to be low on fuel. By the summer of 2001 the Iraqi IADS had also begun targeting U.S. Navy E-2C Hawkeye surveillance aircraft. One Hawkeye crew reported observing the smoke trail of what its pilot thought at the time was an Iraqi SA-3 SAM that had been fired into Kuwaiti airspace (where the Hawkeye was orbiting) in an attempt to shoot it down.18

It was in light of this increasingly aggressive Iraqi activity that General Franks suggested during his briefing to President Bush on December 28, 2001, that the no-fly zones might be leveraged as a convenient framework within which to conduct the initial preparation of the battlespace for any future allied campaign against Hussein’s regime. Shortly thereafter, at the March 2002 CENTCOM component commanders’ conference at Ramstein, General Moseley formally suggested that CENTAF’s planners begin thinking about how they might take advantage of a stepped-up pace of operations in the no-fly zones to help shorten the time between A-day and G-day. By this time it had become clear that only Operation Southern Watch would be involved because the Turkish government was unlikely ever again to authorize an expanded Operation Northern Watch out of Incirlik to include major offensive strikes.19

Once this idea gained the blessing of CENTCOM and the Bush administration in principle, a more detailed concept of operations for the stepped-up patrolling of the southern no-fly zone was considered and refined at a meeting of air operations planners from CENTAF, USAFE, and Joint Task Force Southwest Asia at Camp Doha, Kuwait, on April 24, 2002. Those planners proposed that allied sorties return to patrolling north of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in aggressive pursuit of opportunities to impart real combat effectiveness to Southern Watch by using the operation as a means for both tactical intelligence collection and gradual kinetic preparation of the battlefield for what might eventually become a major offensive to liberate Iraq. CENTCOM’s director of operations, Major General Renuart, recalled in an interview with respect to this changed planning focus: “If the Iraqis keep giving us ROE [rules-of-engagement] triggers, we’ll keep degrading them.”20

The standing ROE for Southern Watch were restructured to meet a new set of operational goals in an expanded effort, now formally code-named Operation Southern Focus, that was scheduled to get under way in June 2002. Those goals included gaining and maintaining air superiority, degrading Iraqi tactical communications, using information operations to achieve strategic and tactical surprise, and eliminating surface-to-surface and antiship missiles.21 A comprehensive new target list was built at a meeting at CENTCOM headquarters in Florida between May 8 and May 10, 2002, characterized by Lieutenant Colonel Hathaway as a “systems approach to targeting” that concentrated on command and control targets associated with Iraq’s IADS in the southern no-fly area. Hathaway noted that “the list was put together using nodal analysis, fused from two separate efforts, one done by the CENTAF information operations flight and the other built at [the Joint Warfare Analysis Center]. It aimed to achieve the most effect with the least damage. It also had ‘revisit’ windows built in, allowing restrikes to be regularly undertaken if our leaflets hadn’t persuaded the Iraqis to desist from repairing the sites.”22

Accordingly, with Operation Southern Focus now shaped by this new planning emphasis and slowly ramping up as the summer of 2002 approached, a de facto undeclared allied air war against Iraq was under way aimed at taking advantage of every opportunity to neutralize key components of Iraq’s IADS and command and control network south of Baghdad piece by piece.23 By that time, even American fighter pilots still at their home bases had begun memorizing mission-specific details of the Iraqi threat environment. One F-16 squadron operations officer recalled efforts by squadron pilots who were preparing to deploy forward in the coming months to “learn everything possible about Iraq’s air defense structure and, more importantly, about their ground forces. Pilots would understand the Iraqi ground order of battle as well as be able to identify doctrinal Iraqi defensive formations from the air.”24 In connection with this expanded effort, General Franks indicated his determination to continue using CENTCOM’s standing response options in prompt reaction to any and all Iraqi provocations, with a view toward rendering Iraq’s IADS “as weak as possible.”25

As the intensity of Southern Focus strike operations mounted, CENTAF planners placed some air-to-air fighters on “Apollo alert” to provide a quick-turn hedge in case the Iraqi air force tried to use the twice-daily Baghdad-to-Basra shuttle flown by an Iraqi Airlines Airbus A320 to mask the movement of its fighters southward into the no-fly zone.26 Evidently undaunted by the escalated allied strikes, an Iraqi SA-2 crew on July 25, 2002, fired at a U-2 flying over southern Iraq at 70,000 feet. The missile’s warhead detonated close enough for its shock wave to reach the aircraft.27

Operation Southern Focus reached full swing in September when General Moseley received approval from Secretary Rumsfeld to begin attacking Iraqi command and control targets routinely.28 This escalated effort was spearheaded by a major strike on September 5, 2002, against the nerve center of Iraq’s western air defenses, the sector operations center at the H-3 airfield in western Iraq. That attack represented the leading edge of a rolling minicampaign to grind down the Iraqi IADS. Not long thereafter, every other sector and interceptor operations center south of the 33rd parallel was successfully attacked and neutralized by precision hard-structure munitions. Concurrently with this expanded effort to chip away at Iraq’s air defense communications network, CENTAF dropped more than four million propaganda leaflets instructing Iraqi IADS operators to refrain from firing on coalition aircraft and warning Iraqi civilians to remain clear of already destroyed IADS fiber-optic nodes.29

During the last week before the formal start of Iraqi Freedom, Southern Watch operations surged to nearly eight hundred sorties a day.30 Halfway through February 2003, reflecting an evident change in the rules of engagement as the formal start of the campaign approached, CENTAF struck identified Iraqi SAM launchers in response to repeated Iraqi AAA firing at coalition aircraft, instances of which had totaled more than 170 since the beginning of 2003.31 Two days before the commencement of the campaign, CENTAF also struck Iraqi long-range artillery positions along the Kuwaiti border and on the Al Faw Peninsula. Several days before that, allied aircraft had begun attacking Iraqi early-warning radars along the Kuwaiti and Jordanian borders, as well as the air traffic control radar at Basra airport, which CENTCOM had determined to be a dual-use facility but had hitherto kept on its no-strike list.32

Allied aircrews operating within the southern no-fly zone were instructed to keep meticulous track of observed enemy tanks, artillery, and other military assets. Some missions were devoted exclusively to such reconnaissance. These so-called nontraditional ISR sorties flown by allied strike aircraft using their Low-Altitude Navigation and Targeting Infrared for Night (LANTIRN) and Litening II targeting pods, radar, fighter data link, and ZSW-1 data link pods for intelligence collection were supplemented by high-flying U-2 reconnaissance aircraft to gather signals intelligence from central Iraq, as well as by a multitude of multispectral imaging satellites. The one RQ-4 Global Hawk high-altitude UAV that was dedicated to Iraqi Freedom began flying long-duration sorties to observe changing patterns in the Iraqi order of battle and monitor movements of Iraqi SAMs and surface-to-surface missiles.33 Fine-grained mapping of the Iraqi early-warning radar system was one critical goal of these sorties. Another was scanning for any signs that Hussein and other top Ba’athist leaders might attempt a dash to political sanctuary in Syria.

Some F-16 pilots initially misunderstood this pioneering use of nontraditional ISR. Maj. Anthony Roberson, an F-16 weapons officer who had been recruited from USAFE’s 32nd Air Operations Group, where he had been serving as head of the combat plans division, to join General Moseley’s CAOC team during the workups for Iraqi Freedom, explained that the tactic required “a different mindset. For a Block 52 [the SEAD version of the F-16 called F-16CJ] guy to be told, ‘I just want you to fly to this destination and take a picture of this, then come back and show it to me,’ would seem to most fighter pilots as a total waste of time. They don’t think it’s an effect, and . . . the value of this mission was misunderstood.”34 Major Roberson went on to point out that such mission applications provided General Moseley with a much-needed picture of Iraq’s most current electronic order of battle. He added: “It is critical for an F-16CJ to be able to swing to that role and use its array of pods to get our pre-strike reconnaissance, thus providing coherent change detection—something that was there yesterday is not there today. We needed to get that information back into the analysts’ hands so that they could tell us what the adversary was doing. The Viper [its pilots’ term of endearment for the F-16] is a good platform for this tasking.”35 The various collection platforms CENTAF employed toward this end revealed the Iraqis to be repositioning high-value military equipment nearly every day, but always in ones and twos or small groups, hoping to avoid the merciless gaze of the E-8 JSTARS.36

During the first week of March 2003, the number of allied CAPs flown over southern Iraq was doubled to give aircrews more experience at operating in a high-threat environment.37 From March 1 until the start of major combat on March 19, allied aircrews flew four thousand sorties into the no-fly zones, in the process acquainting themselves with various procedures that had been established for the impending campaign and further familiarizing themselves with mission-related details of southern Iraq. Of this heightened operating tempo, a Pentagon spokesman noted that “we also want to establish different looks, different flight patterns, in order to preserve some element of tactical surprise.”38 The carrier air wings embarked in Kitty Hawk, Constellation, and Abraham Lincoln took turns participating in these patrols, with F-14s and F/A-18s armed with LGBs and supported by E-2Cs launching on combat sorties day and night. The heightened sortie rate in such a small and congested block of airspace made mission management particularly demanding.

The assistant director of operations of the 77th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron at the time, Lt. Col. Scott Manning, described a harrowing near-miss during the night of March 5, 2003, while he was leading the SEAD escort force in support of a U-2 as the latter skirted the Baghdad-area Super MEZ:

During the second refueling between tanker operations and NVG [night-vision goggles] transition, I had a very close call with [my wingman,] Rowdy. We pulled off the tanker in a right-hand climbing turn, and it was pitch black. Rowdy rotated his light switch to “off.” Having been watching him in the right turn, I could not see that he had stopped his turn. I, however, stayed in my right turn while perceiving him to still be in his. In retrospect, I should have rolled out and called for his lights. Instead, I stayed in the turn and reached up to pull my goggles down. I heard the blast of the mighty GE-129 [jet engine] pass right over my canopy, at which point I looked up to the left (keep in mind I am still in my right turn) only to see Rowdy now out on my left side and only about 20 feet away. I was fortunate that Rowdy had looked at me during this and pulled back on his stick to let my aircraft pass underneath him.39

The minicampaign against the Iraqi IADS that unfolded under the aegis of Southern Watch during the months immediately preceding the war significantly degraded Iraq’s air defense capabilities within the southern no-fly zone. That ramped-up effort had no effect in the least, however, against Iraqi IADS assets fielded in and around Baghdad, which General Leaf characterized as more robust than the defenses that had been in place there on the eve of Desert Storm more than a decade before. Iraq, Leaf said, had marshaled all of its assets for a vigorous defense of its capital city: “Countrywide, they are weaker. In Baghdad, they are stronger because they have brought everything in.” Iraq’s echeloned defenses around the capital included SA-2, SA-3, and SA-6 radar-guided SAMs; man-portable infrared SAMs; and AAA.40 Furthermore, Iraqi air defense technicians had met with their Serbian counterparts after Operation Allied Force in 1999 and had carefully studied the unique tactics Serb air defenders had applied against NATO’s combat aircraft.41

The Iraqi air force had continued to fly as many as a thousand training sorties a month in the airspace between the two no-fly zones right up to the eve of the campaign’s start, and thus could not be completely discounted as a threat to allied forces.42 Just a month before the campaign began, the Iraqis conducted a rare MiG-25 reconnaissance mission toward the west in an attempt to assess allied force dispositions.43 Barely a month before that, on December 23, 2002, a MiG-25 had succeeded in downing an MQ-1 Predator that had been especially configured with a Stinger infrared missile.44 General Moseley later explained that a special projects effort had been initiated to configure the Predator, which normally mounts AGM-114 Hellfire air-to-ground missiles, with the infrared-guided Stinger with the intent to lure the Iraqi air force to come up and engage it with a fighter. Although the Predator was shot down in the end, the bait worked and provided valuable updated intelligence on the MiG-25’s radar performance parameters and the Iraqi command and control system.45

Within the context of Operation Southern Focus, the coalition responded to 651 incidents of Iraqi firing on allied aircraft by dropping 606 bombs on what General Moseley called a “wider set of air defense and related targets.”46 Under Southern Focus, allied aircrews were authorized to attack Iraqi IADS-related facilities that had not directly threatened allied aircraft but were associated with the air defense system. Fiber-optic cable repeaters were of particular interest. Because they are about the size of manhole covers, they called for especially precise munitions delivery. Allied aircrews attacked known fiber-optic nodes whenever possible in an attempt to force Iraqi air defenders to rely on their more vulnerable shorter-range acquisition and tracking radars, which could be more easily monitored and jammed. These expanded responses continued right up to the formal start of Operation Iraqi Freedom on the night of March 19.

Toward the end of Southern Focus, three defensive counterair CAP stations were established inside southern Iraq, with the western position moved forward to include the airspace above the 33rd parallel at the time initial SOF operations began on the ground on March 19 (see below). Although no Iraqi aircraft attempted to fly at any time during the three-week campaign, those CAP stations were established and maintained lest Iraqi pilots try desperation attacks against vulnerable allied aircraft like tankers and ISR platforms operating in rear areas.47

By March 18, 2003, CENTCOM’s air component had flown 21,736 combat sorties into the southern no-fly zone under the aegis of Southern Focus and had destroyed or damaged 349 specific targets. The 651 known instances of Iraqi surface-to-air fire directed against CENTAF aircraft during this eight-month period were all ineffective.48 After the campaign ended, General Moseley acknowledged that the heightened intensity of allied air operations may have elicited a more intense Iraqi response, giving allied aircrews more opportunities to attack ground targets of all types: “We became a little more aggressive based on them shooting more at us, which allowed us to respond more. Then the question is whether they were shooting at us because we were up there more. So there is a chicken-and-egg thing here.”49

Viewed in hindsight, Southern Focus conferred an early advantage on CENTCOM’s effort to gain total control of the air over a large portion of Iraq once the full-up campaign was ready to be launched. More important yet, it also was a key enabler of CENTCOM’s ultimate decision to commence air and ground operations almost simultaneously because it allowed General Moseley, in effect, to start the air war more than eight months in advance of the formal execution of OPLAN 1003V. By that time, General Jumper observed, “we felt that [Iraq’s air defenses] were pretty much out of business.”50 Former Air Force chief of staff Gen. Merrill McPeak later added that it was incorrect, strictly speaking, to suggest that there had been no independent preparatory air offensive prior to the unleashing of allied ground forces against Iraq from Kuwait, as had been the case for nearly six weeks during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. On the contrary, McPeak noted, because of the prior air preparation that had been made possible under the aegis of Southern Focus, “Iraq’s air defenses stayed mostly silent, and our aircraft were able to begin reducing opposing ground forces immediately” once the major combat phase of Iraqi Freedom was under way.51

Preparatory Air-Supported SOF Operations

Precursor operations to pave the way for Iraqi Freedom also took place on the ground. Months before the campaign began, Army Special Forces A-teams (the nickname commonly used to denote numbered twelve-man Operational Detachments Alpha) were assigned individual provinces in Iraq and were directed to study their populations, terrain, infrastructure, and social setting.52 As the onset of formal combat neared, allied SOF teams rehearsed activities planned for the western Iraqi desert in the Nellis AFB range complex in Nevada. They subsequently deployed to the war zone as an integrated and combat-ready force because they had already trained together as such.53

In a related move, on February 20, 2002, the first CIA team entered the Kurdish area of northern Iraq to lay the groundwork for a planned insertion of paramilitary teams that would comprise the CIA’s northern Iraq liaison elements.54 CIA operatives on the ground in Iraq soon began providing solid human intelligence reports on Iraqi air defenses hitherto unknown to CENTCOM.55 CENTCOM asked the CIA to provide geographic coordinates for the reported sites, and once those coordinates were in hand, successfully struck the sites during Southern Focus operations. Woodward later reported that “the quantity and quality of [this] intelligence . . . was dwarfing everything else.”56

As allied preparations for war continued toward the final countdown, CIA operatives reportedly recruited an active-duty Iraqi air force Mirage pilot and a MiG-29 mechanic. From those two sources the CIA learned that Iraq’s air arm was in a state of near-collapse and was capable of performing only suicide missions, and that Iraqi pilots were feigning illness on scheduled flying days to avoid having to fly barely airworthy aircraft.57

On March 19 at 2100 local time, nine hours before the scheduled start of the ground war, more than fifty allied SOF units (including both Special Forces A-teams and similar British and Australian units) covertly entered Iraq’s western desert and neutralized some fifty enemy observation posts along Iraq’s borders with Jordan and Saudi Arabia. As those initial SOF operations began to unfold, RQ-1 Predator UAVs flying overhead streamed live video into the CAOC, showing the observation posts being systematically taken down in accordance with the plan. Additional SOF teams poured into the western desert and fought a series of fierce battles to secure the areas from which Iraq had launched Scud missiles against Israel in 1991. The principal aim of this operation was to give Israel every incentive to refrain from intervening militarily.58 Allied SOF units also promptly isolated and captured the H-1, H-2, and H-3 military airfields in Iraq’s western desert where chemical munitions and Scud missiles had been stored prior to Operation Desert Storm.

The SOF operations were backed up by airborne strike aircraft armed with PGMs, including thirty-six F-16C+ fighters of the Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve Command, eighteen A-10s, eight RAF Harrier GR7s, ten B-1s, four RAF Tornado GR4s on call if needed, and a variety of airborne and space-based ISR assets.59 To support the counter-Scud mission and other SOF operations in the western desert, General Moseley had established the 410th Air Expeditionary Wing composed of aircraft from the RAF in addition to the Guard and Reserve. This was the first instance in which a SOF task force drew all of its apportioned CAS, as well as much of its air interdiction support, from a single wing that had been expressly task-organized for the purpose. In a major first in the annals of air-land operations, General Franks gave General Moseley control of the counter-Scud mission as the supported component commander. He also gave the subordinate commander of Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force (CJSOTF) West the responsibility for interdicting ground-based time-sensitive targets in support of that mission. Never before had the air component of a joint task force been given operational control of an extensive portion of enemy territory; nor had a SOF task force commander on the ground served in a supporting role to the air component commander.60

The vice director of operations on the Joint Staff at the time, Maj. Gen. Stanley McChrystal, noted later during the campaign that these SOF-dominated operations represented “probably the widest and most effective use of special operations forces in recent history.”61 In contrast to the five hundred or so coalition SOF troops who deployed for Operation Enduring Freedom, active SOF involvement in Iraqi Freedom soared to nearly ten thousand personnel from U.S. and allied services. During the counter-Scud operations in the Iraqi western desert, a commentator noted, allied SOF teams went “quail hunting” with harassing raids intended to flush out Iraqi military units, “which then became targets for U.S. air strikes. Indeed, air power proved to be the Special Forces’ trump card.”62

The B-1s used in these operations were essentially precision bomb-carrying trucks, each loaded with as many as twenty-four JDAMs. They also were equipped with a Ground Moving Target Indicator (GMTI) radar that could detect any Iraqi ground force movement.63 (At a unit cost of less than $20,000, the JDAM tail-kit that was affixed to standard 2,000-pound and 1,000-pound general-purpose high-explosive bombs during the major combat phase of Iraqi Freedom in 2003 yielded a nominal 10-meter attack accuracy against mensurated target coordinates that had been further reduced to a 3-meter circular error probable, barely more than the length of the munition.)64 New onboard jamming systems and ALE-50 towed decoys protected the B-1s in defended Iraqi airspace, with the decoy reportedly having performed “smashingly.”65

Allied SOF teams operating in the western desert encountered unanticipated resistance from Iraqi ground units and required greater-than-expected air interdiction and CAS. The counter-Scud mission eventually evolved into three additional missions: maintaining an allied western presence, blocking attempted escape of Ba’athist leaders, and direct action against Iraqi ground forces. The SOF units, supported by the air assets noted above, quickly established fairly secure operating areas and were able to block both escape and incoming materiel reinforcements. In the process, all Iraqi forces in the region were destroyed or forced to surrender, obviating the need for allied conventional ground forces.66 Commenting on this operation shortly after the campaign ended, a senior U.S. official noted that “there were a lot of dead bad guys left in that desert who were planning some really nasty things, from shooting Scuds at Israel to blowing up oil and air fields to messing with Jordan.”67 In fact, there was no indication after the campaign ended that any of the allied SOF teams encountered Iraqi Scuds.68

Allied SOF operations in northern Iraq followed a roughly similar pattern. Because the issue of Turkish basing and overflight had not yet been resolved, the SOF component started with only a small presence of forces on the ground, with B-1s providing support. The CAOC was unable to provide more significant air support because CENTAF could not use its strike aircraft based at Incirlik. As a result, air superiority over the area had not yet been established in a situation in which tankers had to be pushed into Iraq to refuel the fighters that were escorting the B-1s. Iraqi troops attempted some halfhearted attacks on Kurdish forces in the north, but they made no determined effort actually to penetrate Kurdish-controlled areas. Iraqi AAA positions did on one occasion fire on 6 MC-130s that were attempting to insert some 250 allied SOF personnel into a predesignated operating area, hitting one and forcing it to make an emergency landing at Incirlik on 3 engines.69

A typical tactical air control party (TACP) of Air Force joint terminal attack controllers (JTACs) operating in northern Iraq consisted of two SOF airmen paired up with a Kurdish Peshmerga militiaman and armed with a .50 caliber sniper rifle and a Viper laser target designator configured with a 50´ magnification telescope.70 The fire support procedures involving kill boxes and the fire support coordination line (FSCL, pronounced “fissile”) that predominated in kill-box interdiction and close air support (KI/CAS) operations in the south (see below) generally did not apply in northern Iraq because there was never a clear moving line of advance for allied forces.71 In light of the largely guerilla-type war that Kurdish Peshmerga fighters were conducting in this part of the war zone, allied aircrews performing CAS missions could determine the precise location of friendly troops on the ground only by contacting them by radio during the final stages of preparation for an air-support attack.72

For the first two days of the war, the aircraft of Carrier Air Wing (CVW) 3 embarked in Harry S. Truman and those of Air Wing 8 in Theodore Roosevelt operating in the eastern Mediterranean could not support allied SOF operations in northern Iraq because they lacked permission to transit the airspace of any of the countries that lay between the carrier operating areas and their likely targets. After Turkish airspace was finally made available to the coalition by D+3, however, numerous carrier-based strike sorties were flown over Turkey and were pivotal in forcing the eventual surrender of Iraqi army units in the north. In the end, having sustained no combat fatalities as a result of enemy fire, a mere thousand SOF combatants enabled by allied air power effectively neutralized eleven Iraqi army divisions in the north, whose troops, by one account, “simply took off their uniforms and walked home.”73 This successful synchronization of allied SOF teams and air power was a direct result of the deep mutual trust relations between the two communities that had been cemented by their highly successful joint combat operations during Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan.74

An Unplanned Start

As D-day neared, CENTCOM had settled on a plan that called for the allied air and ground offensives to kick off more or less concurrently, with a view toward undermining the cohesiveness of Iraq’s highly centralized political and military establishment. A heavy opening round of air attacks would be closely followed by allied ground forces advancing in strength to secure such time-sensitive objectives as the oil fields in southern Iraq. This carefully arranged plan was abruptly preempted on the afternoon of March 19, 2003, however, by an eleventh-hour report from CIA director George Tenet that the intelligence community had learned of a “high probability” that Saddam Hussein and his two sons Qusay and Uday would be closeted with their advisers for several hours in a private residence in a part of southern Baghdad known as Dora Farms.75 Tenet took this information directly to Secretary Rumsfeld, and both men went to President Bush with the news that a timely decapitation opportunity had arisen that might bring down the Ba’athist regime in a single stroke and perhaps make the full-scale allied offensive unnecessary.

Earlier that day, President Bush had held a final video teleconference with General Franks, who was in the CAOC at Prince Sultan Air Base with General Moseley, and CENTCOM’s other component commanders. The president had polled the component commanders one by one, asking each in turn if he had what he needed to proceed comfortably with the planned campaign. General Moseley replied: “My command and control is all up. I’ve received and distributed the rules of engagement. I have no issues. I am in place and ready. I have everything we need to win.” The other commanders replied in much the same way. Franks then reported to Bush: “The force is ready to go.” Bush replied: “I hereby give the order to execute Operation Iraqi Freedom.”76 The plan called for forty-eight hours of covert operations to insert SOF teams into Iraq as the campaign’s initial moves. At that point, thirty-one SOF teams quietly entered western and northern Iraq.

Up to that point, CENTCOM’s campaign plan had called for A-day to commence two days later on March 21 at 2100 local time, nearly 24 hours after the scheduled start of the allied ground push. The tantalizing prospect of beginning—and ending—the campaign with a single surgical strike, however, was simply too good to pass up. President Bush approved the decapitation attempt. A CAOC staffer later observed that OPLAN 1003V in its initial planning stages had been aimed at Hussein principally in a figurative sense; now, the Iraqi dictator “would literally be in the crosshairs.”77

General Myers immediately phoned General Franks and asked him if he could prepare the needed TLAMs within two hours to meet the required time-on-target. Franks replied that he could. General Myers subsequently reported intelligence indications that there was a hardened bunker within the target complex that TLAMs could not penetrate, thus necessitating the use of 2,000-pound penetrating EGBU-27 laser-guided and satellite-aided bombs that could be delivered only by F-117 stealth attack aircraft. Franks initially told Myers that he did not believe he could have an F-117 ready to launch in sufficient time, but then he checked with General Moseley in the CAOC.

The air component commander immediately summoned his subject-matter expert on the F-117, Maj. Clinton Hinote, and told him: “The answer I owe the president is, is this doable, and what is the risk?” Major Hinote pondered the question for a moment and replied: “Sir, it is doable, but the risk is high.”78 Hinote outlined various operational considerations that would figure in any such gamble, offered a couple of alternative strike options that might work, and listed support assets that would be needed to maximize the chance of mission success. Armed with Hinote’s input, General Moseley informed Franks that a single F-117 could promise only a 50 percent chance of mission success and that it would take two of the stealth aircraft to ensure an effective target attack. Moseley added that the bombs could be salvoed in pairs, even though that delivery mode had never before been attempted.

As good operators would naturally be expected to do with a major offensive looming, mission planners in the 8th Fighter Squadron that operated the forward-deployed F-117s had already been “leaning forward” and had arranged to have one aircraft fully loaded with the penetrating munitions that would be required for any such short-notice mission. Intelligence experts in the CAOC, however, did not have accurate information regarding the precise location of the presumed bunker. CAOC weaponeers hypothesized that the bunker would most likely be buried beneath a field near the main house in the Dora Farms complex, and accordingly spread four weapon aim points across the field to maximize the likelihood that one bomb would penetrate the suspected bunker.79 (Only after the campaign ended and U.S. forces were able to examine the site did it become certain that there was no underground bunker and no evidence that Saddam Hussein had been at Dora Farms at the time.)80

As soon as it was clear that the two F-117s could be made ready in sufficient time, General Franks told the president that he needed a committal decision from the White House by 1915 eastern standard time if the aircraft were to have any chance of safely exiting Iraqi airspace before dawn. The sun would rise over Baghdad the following morning at 0609 local time, with first light occurring about a half-hour earlier, rendering the F-117s visible and hence vulnerable to optically guided Iraqi AAA fire. President Bush gave the “go” order at 1912, three minutes before Franks’ stipulated deadline.

The F-117s took off from Al Udeid Air Base at 0338 local time, less than ten minutes before the cutoff time of 0345 local. CAOC mission planners hastily scrambled to round up needed tanker support for the F-117s by diverting tankers that had been flying night missions near southern Iraq in connection with Southern Focus. The TLAMs in the scheduled strike package were then launched in sequence as planned, starting at 0439. They would arrive at their assigned aim points within minutes after the impact of the EGBU-27s as SOF operations concurrently unfolded in the west and south and on the Al Faw Peninsula. Immediately before the F-117s’ scheduled time-on-target, four F-15E Strike Eagles, in the one and only use of the GBU-28 hard-structure munition throughout the entire campaign, successfully neutralized the interceptor operations center at the H-3 airfield in the western Iraqi desert.81 That was the last bomb dropped during a Southern Watch mission.

The aerial attack against the three-building Dora Farms complex was conducted just before sunrise at 0536 Baghdad time by the two F-117s, each of which dropped two EGBU-27s directly on their assigned aim points. Scant minutes after those four bombs detonated, a wave of conventional air-launched cruise missiles (CALCMs) from B-52s operating at safe standoff ranges struck the Dora Farms compound, followed by forty Navy TLAMs launched from the North Arabian Gulf and Red Sea by four surface warships (Milius, Donald Cook, Bunker Hill, and Cowpens) and two nuclear fast-attack submarines (Montpelier and Cheyenne), partly to help further suppress Iraqi radar-guided SAM defenses in the area.82

This was the first combat use of the EGBU-27, which featured both laser guidance for precision targeting and GPS guidance for all-weather use, a combination that greatly improved its combat versatility.83 The F-117s were supported by Air Force F-16CJs that performed preemptive defense-suppression attacks against selected Iraqi SAM sites and by three Navy EA-6B Prowlers that were launched on short notice from Constellation to jam enemy IADS radars.84 As the preplanned time for EGBU-27 weapon release neared, a partial cloud cover obscured the designated aim points within the target complex. A lucky break in the cover gave the F-117 pilots roughly six seconds to identify the target visually and drop their bombs. The pairs of munitions in each drop were clustered so closely together after release that they almost collided on their way to the target. The two pilots observed all four detonations, which occurred about ninety minutes after President Bush’s deadline for Hussein and his two sons to leave Iraq had expired.

Capt. Paul Carlton III, an F-16CJ pilot who was airborne that night leading a two-ship element, later recalled the campaign’s impromptu opening as he observed hints of its evolution from a distance:

On March 19/20, we were flying on-call SEAD. . . . I was a night guy, flying only at night, and it was early in the morning. I had one more vul [vulnerability period] to cover before I went home. We were covering six-hour vul times, where we’d come away to get gas when we needed it and then go back in again. I came out of the [operating area], contacted the appropriate agency, and they said, “Copy. You’re going to support Ram 01.” That’s all I got. Who’s Ram 01!? I had no idea what was going on. I asked, “Can you tell me who Ram 01 is, what their TOT [time-on-target] is and where they’re going?” I got nothing back. . . . The [rules of engagement] at the time were that we couldn’t shoot or drop anything unless we were given permission to do so. . . . So I sent [my wingman] off to get permission to fire our weapons if needed, and at the same time I start looking for Ram 01 on the radio. I had no idea what he was or what was going on. . . .

Ram 01 came up on the radio and told me roughly where he was and the coordinates of where he was going. He also gave me the coordinates of his IP [initial point] and his target, which I plugged into my jet so as to figure out where he was going and what his target was. His target plot fell into the little map of Baghdad. That clued me in to what he was about to do, and I knew that things were about to get much more exciting.

Having learned the TOT and seen where he was going, I knew all I needed to know. I knew what threats he was up against, and now I was thinking about how best I could support him. . . . Having devised a basic strategy, I flew back into the [area of operations], but chose not to go up near his target, even though we were now allowed to cross the no-fly zone. The F-16 is a radar-significant target, and I didn’t want to trip anything off or stimulate the air defenses before they needed to be. I never heard anything else from Ram 01, which, thinking about it now, makes sense to me as the pilot always “cleans up” as they go to war [i.e., the F-117 retracts its communications antennas when entering defended airspace].85

Carlton and his wingman continued to watch the Super MEZ for about an hour. “Then,” he said,

I hit Bingo fuel [the fuel level at which an aircraft must either initiate a return to base or depart the area to seek a tanker]. I’ve not seen anything happen or anything to suggest what’s happened to Ram 01, so I told the controlling agency, “I’m Bingo and have to go home.” I got handed off to different agencies and headed back to the tanker down south to get gas for the trip home. We were on the tanker when Ram 01 came over the radio and said, “Tanker 51, Ram 01 behind you and checking in for gas.” As I came off the tanker with my wingman, I looked behind me and there’s this Stinkbug [fighter-pilot slang for the F-117] taxiing up. That was the first clue that I had that we’d just helped start the war.86

Roughly two hours after the mission had been completed and all its aircraft had safely returned, President Bush announced to the nation and the world: “On my orders, coalition forces have begun striking selected targets of military importance to undermine Hussein’s ability to wage war. These are the opening stages of what will be a broad and concerted campaign. . . . I assure you this will not be a campaign of half measures, and we will accept no outcome but victory.”87 Franks later recalled: “We did not want President Bush to speak in a way that sounded good to America and our allies, but inadvertently compromised our plan.”88 Shortly after the eleventh-hour decapitation attempt, the chairman of the JCS, General Myers, declared that “regime leadership command and control is a legitimate target in any conflict, and that was the target that was struck last night.”89 Early reports that Hussein had been killed or injured in the attack proved to be false.90

Iraq promptly responded to the attempted decapitation attack by launching five surface-to-surface missiles into Kuwait in a move that obliged allied troops and Kuwaiti civilians to don chemical warfare protective garb. One of those missiles, an Ababil 100 (an Iraqi variant of the Soviet FROG [free rocket over ground] missile), was fired from a launch basket south of Basra. USS Higgins, a Navy Aegis destroyer positioned in the North Arabian Gulf, detected the missile on radar within two seconds after its launch, determined its launch point, and generated a firing solution within fourteen seconds. An Army Patriot PAC-3 SAM from one of the twenty-seven Patriot batteries stationed in Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia destroyed the Iraqi missile in flight.91 Moments thereafter, a pair of airborne F-16s geolocated the two offending Iraqi mobile missile launchers and destroyed them.92

Technical evidence suggested that Patriot PAC-3 SAMs destroyed all of the intercepted Iraqi missiles, including the Ababil 100 and an Al Samoud 2 (an Iraqi modification of the Soviet SA-2 SAM with a maximum range of about 112 miles). One Iraqi missile that got through allied defenses was believed to have been a Chinese-made CSSC-3 Seersucker cruise missile that flew low over the water from the Al Faw Peninsula into Kuwait, beneath the field of regard of nearby Patriot radars that were scanning for higher-flying ballistic missiles.93 Four of the incoming Iraqi missiles were intentionally not fired at because they posed no threat. Two landed in the water, one impacted in the empty desert, and the fourth exploded shortly after being launched.94 Later that day, Franks reported to Rumsfeld that “we have air supremacy in the battlespace.”95

The abrupt change in the initially planned timeline for Iraqi Freedom occasioned by the decapitation attempt had far-reaching consequences. Fearing a loss of tactical surprise, heightened vulnerability of exposed allied ground troops in Kuwait to missile and artillery attack, and an Iraqi move to torch the country’s vital oil wells in a punitive response, CENTCOM unleashed the lead elements of deployed Army, Marine Corps, and British ground troops thirty-six hours ahead of the originally planned start of heavy air operations, essentially reversing the plan that had been so painstakingly developed during the preceding months.96 That eleventh-hour reversal was rendered more palatable for CENTCOM because its air component had already established air superiority over southern Iraq by means of Operation Southern Focus, thereby freeing up the coalition’s strike aircraft to concentrate almost entirely on supporting the allied ground units.

The most detailed of the postcampaign assessments of V Corps’ land offensive noted that

crossing the berm [into southern Iraq] was a major combat operation. Erected to defend the Kuwaiti border by delaying attacking Iraqi troops, the berm now had the same effect on coalition troops heading the other way. Breaching in the presence of Iraqi outposts required rapid action to deny the Iraqis the opportunity to attack vulnerable coalition units while they were constrained to advance slowly and in single file through the lanes in the berms. . . . Literally a line in the sand, the berm was a combination of massive tank ditches, concertina wire, electrified fencing, and, of course, berms of dirt. The breaching operation required four major tasks—reducing the berms, destroying the defending Iraqi forces along the border (mostly observation posts), establishing secure lanes through the berms, and then passing follow-on forces through to continue the attack into Iraq.97

In conjunction with this major movement into southern Iraq by V Corps, Navy sea-air-land commandos (SEALs) and British Special Air Service (SAS) troops conducted an air assault on an oil manifold and metering station on the tip of the peninsula and promptly secured that high-value objective. The start of the allied push into the Al Faw Peninsula was set for 2200 local time on the night of March 20, 2003. It was preceded by supporting JDAM attacks by carrier-based F/A-18s as well as by highly accurate optically directed cannon fire from AC-130 gunships that were orbiting nearby. Carrier-based jets also attacked command and control targets in southern Iraq and delivered leaflets containing capitulation instructions to Iraqi troops who might be inclined to surrender without a fight. Promptly on the heels of these preparatory air attacks, allied SOF and regular forces entered on the ground and secured the remainder of the objective.

A coalition SOF contingent crossed into Iraq from Arar in Saudi Arabia that same night, with a similar contingent launching from a more northward departure point to seize and hold the strategically vital H-2 and H-3 airfields in the Iraqi western desert and the equally important Haditha dam. This operation was backed by a strong air element of B-1s, F-15Es, and F-16s carrying LGBs and satellite-aided JDAMs. The SOF teams marked Iraqi vehicles and other targets with hand-held laser designators, and the strike aircraft destroyed or disabled seventeen ZSU-23/4 AAA guns and some twenty-three other Iraqi armored vehicles, as well as numerous trucks and barracks. Shortly thereafter, two C-17s that had flown nonstop from North Carolina landed on an unprepared strip in western Iraq, in the first direct combat insertion of a U.S. mechanized force.98

Allied strike and combat support aircraft were subsequently launched from carriers in the North Arabian Gulf and selected land bases throughout the theater to begin the air war in a measured fashion during the night of March 19–20. Although the ATO for that day (the carefully preplanned D-day for Operation Iraqi Freedom) generated 2,184 sorties in all, the initial round of air strikes was carefully meted out, as one defense official put it, to “see if we can try to tip things first.”99 Secretary Rumsfeld continued to urge Hussein’s government to concede, saying, “We continue to feel that there’s no need for a broader conflict if the Iraqi leaders act to save themselves.”100

The initial strikes were directed mainly against Republican Guard headquarters and related targets with the goal of trying to separate the Iraqi rank and file from the regime. As one account later recalled in this respect, the allied coalition “did not attack with overwhelming force, and operations over the first 40 hours were characterized by judicious use of the minimum force necessary.”101 General Moseley’s chief of strategy described the underlying nuances of the minimum-force approach as follows:

While all planners, both air and ground, began with a desire to go in with overwhelming force (General Franks’ initial Generated Start), the president and secretary of defense kept pushing us toward a leaner and more quickly moving force. This forced me to be more deliberate with effects-based planning. It is fairly easy to get many of the desired effects when you have overwhelming force. In the end, with a more fine-tuned effects-based approach, we found ways (both kinetic and nonkinetic) to achieve the desired effects with our forces split against all of the planned major combat phase objectives at once.102

By the end of the campaign’s first full day on March 20, the air component was well into the Scud hunt in the Iraqi western desert; allied SOF teams had begun infiltrating into the west, north, and south of Iraq and were in partial control of the western desert that constituted a quarter of Iraq’s entire territory; and the land component’s forces were fully poised in attack positions on the planned line of departure.103 Remarking on CENTCOM’s last-minute need to reset its plans, British defense analyst Michael Knights observed that “in contrast to the beginning of Operation Desert Storm, which had been a triumph of orchestration, the opening of Operation Iraqi Freedom would prove to be a triumph of improvisation.”104

The initial hope that Hussein’s regime might quickly implode led CENTCOM at the last minute to remove many high-value targets within the city limits of Baghdad from the initial target list (see below). A senior CAOC staffer later explained this sudden truncation of the initially planned ATO for that day: “There was a hope that there would be a complete and utter collapse of the regime early on. In order to let that come to fruition, [CENTCOM’s leaders] initially held back on those targets.”105 As it turned out, however, many of the air component’s planned A-day southern targets had been either already destroyed by earlier Southern Focus attacks or overrun by the advancing land component and SOF units during the first day.

The Full Campaign Begins

The actual start of preplanned offensive air operations, designated A-hour by CENTCOM, took place precisely on schedule at 2100 Baghdad time on the night of March 21 with large-scale air attacks that would total more than 1,700 sorties in all, including 700 strike sorties against roughly 1,000 target aim points and an additional 504 cruise-missile attacks in the opening round. This start sequence had been essentially set in stone almost from the outset of campaign planning because of the complex and inflexible orchestration of allied strike platform takeoff times required to enable those aircraft to achieve a simultaneous time-on-target in the Baghdad area from widely dispersed operating locations ranging from nearby Kuwait all the way to the United Kingdom and the continental United States.

The commander of Carrier Air Wing 2 in Constellation, who led the initial strike force, recalled that he deemed the potential for midair collisions both inside and outside Iraq

one of the greatest risks we faced. . . . In concert with the CAOC planners and our CVW-14 teammates, we created simple procedural airspace deconfliction measures—three-dimensional “highways in the skies,” complete with off-ramps, reporting points, and altitude splits that helped mitigate the midair hazard. Still, the prudent aviator always stayed on altitude, did belly checks, and kept his head on a swivel when joining the tanker. . . . The indispensable U.S. Navy and Marine Corps EA-6B Prowlers provided continuous multiple-axis jamming in support of approximately 70 aircraft attacking nearly 100 different targets throughout Baghdad.106

The target list for the opening-night attacks consisted of known or suspected leadership locations, regime security, communications nodes, airfields, IADS facilities, suspected WMD sites, and elements of Iraq’s fielded forces. Regime security targets on the initial strike list, approximately 104 in all, included facilities of the Ba’ath Party, Fedayeen Saddam, Internal Intelligence Service, Special Security Organization, Directorate of General Security, Special Republican Guard, and the personal security units that were assigned to protect the regime’s leaders. The roughly 112 communications targets that were attacked during the initial round consisted of cable and fiber-optic relays, repeater stations, exchanges, microwave cable vaults, radio and television transmitters, switch banks, satellite antennas, and satellite downlinks. Sea- and air-launched cruise missiles were the main weapons used in the initial wave, followed by a concentration of F-117 and B-2 stealth attack aircraft that were supported by fully integrated conventional strike and electronic warfare aircraft packages. During one of those attack segments, a B-2 dropped two 4,700-pound GBU-37 satellite-aided hard-structure penetrators on an Iraqi communications tower in Baghdad. (The B-2 can carry eight GBU-37s and is the only aircraft in the Air Force’s inventory configured to deliver the munition.)107

Although it could not be immediately determined how many Ba’ath regime leaders, if any, were caught by surprise and killed in these attacks against headquarters buildings, command centers, and official residences—some fifty-nine buildings in all—the impact of the attacks was broadly reflected in the failure of the leadership to attempt to rally the Iraqi people, the limited scope and impact of Iraqi information operations, the slowness of the Iraqi army to react, the absence of any observed enemy ground maneuver above the battalion level, the slowness of Iraqi forces to reinforce Baghdad, and the complete failure of the Iraqi air force to defend Iraqi airspace. The general absence of hard and reliable intelligence on Iraqi WMD sites precluded a robust attempt against that target set, although such WMD delivery systems as surface-to-surface missiles, artillery, and UAVs were struck whenever they were located and positively identified. CENTCOM made a high-level decision not to focus attacks on WMD infrastructure unless there were indications of an imminent threat to coalition forces.108

Initial SEAD Operations

The defense-suppression portion of the A-hour offensive unleashed on the night of March 21 was led by a barrage of allied sea- and air-launched cruise missiles that were targeted against the eyes, ears, and lifeblood of Iraq’s still-intact and highly distributed IADS. In this initial assault wave, more than one hundred TLAMs took down the ring of high-power, low-frequency acquisition and tracking radars that surrounded Baghdad. The capital city’s main defense node was its air defense operations center, which fed threat information to subordinate sector operations centers that, in turn, fed that information to interceptor operations centers. All of these nodes were attacked, as were microwave landlines and fiber-optic cables that relayed air defense information and key long-range early-warning radars.109

These initial counter-IADS attacks struck the most critical fire control and communications nodes of the many SAM batteries aggregated in the Super MEZ around Baghdad and Tikrit, as well as leadership and other regime facilities in central Iraq. The Super MEZ, which appeared on aircrew navigational charts as a racetrack with extensions on the opposite sides of each end (see map 2.2), consisted of a profusion of SA-2, SA-3, and SA-6 missile launchers, as well as some French-made Roland SAMs and at least one American-produced I-Hawk SAM complex that had been captured when Iraq occupied Kuwait in late 1990 and early 1991. Each radar-guided SAM site was also accompanied by a profusion of AAA guns of calibers ranging up to 100 mm.110 Many of these sites had never been precisely geolocated by U.S. intelligence.111

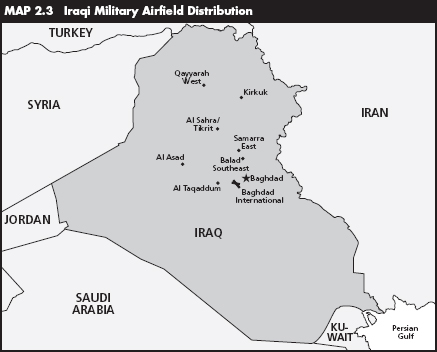

Concurrently, all major airfields of the Iraqi air force were rendered unusable by JDAM attacks that cratered the main runways and taxiways (see map 2.3). CENTAF planners had intended to use TLAMs against the SA-2 and SA-3 sites defending fighter airfields, but the absence of good real-time intelligence confirming their locations most likely precluded those attacks.112 These cruise missile strikes were followed at 2146 by the first attacks by stealthy B-2s and F-117s. Eight of the twelve F-117s scheduled in this initial attack wave had to abort without expending their munitions because of their inability, in the confusion of the opening hours, to make their scheduled tanker connections. By 2300, nonstealthy Air Force and Navy strike aircraft had entered the fray in large numbers, bringing the total number of target aim points attacked to about a thousand by the end of the first night of air attacks. As a result of the assessed effectiveness of these attacks, General Moseley deemed it safe to push the first E-3 AWACS aircraft into Iraqi airspace to support joint and combined air and SOF operations in northern Iraq.113 As a testament to the extent of air dominance achieved by the coalition at that point, B-1s operated in the heart of the most heavily defended Iraqi airspace, including night missions on the campaign’s second day and daylight missions beginning on the third.114

Source: Adaptation by Charles Grear based on CENTAF map

Source: Adaptation by Charles Grear based on CENTAF map

During the course of these initial counter-IADS attacks, allied strike aircraft, supported by SEAD assets armed with AGM-88B/C high-speed antiradiation missiles (HARMs), used penetrating hard-structure munitions to attack underground command centers and overwhelm Iraq’s IADS operators, who thereafter elected to launch all of their SAM shots ballistically (i.e., without radar guidance). The cutting edge of the air component’s SEAD capability during these initial forays into still heavily defended Iraqi airspace was the Air Force’s F-16CJ, which had been expressly configured to perform this demanding mission.115

The SEAD escort mission required the F-16CJs fly in close coordination with strike aircraft en route to their targets, remaining alert to Iraqi IADS radar activity and specific pop-up SAM threats, and firing HARMs periodically from standoff ranges in a preemptive effort to suppress the Iraqis’ ability to engage the strikers with radar-guided SAMs. One account explained that this preplanned HARM operating mode, called preemptive targeting (PET),

allows [the missile] to be fired at a suspected [SAM] site regardless of whether [the site] is emitting or not. Based on precise and thorough preflight planning, the timings are calculated so that the HARM will be in the air as the strikers are over the target, or at their most vulnerable point. If the threat radar comes on line during the missile’s time of flight, the HARM’s seeker will detect the radar energy and issue corresponding guidance commands to steer it toward the source. The main priority . . . was to get threat emitters off the air as soon as possible, or to dissuade them from coming on line at all.116

A related tasking for the F-16CJs came in the form of so-called lane SEAD, in which the aircraft patrolled the ingress and egress lanes used by coalition strike aircraft. Because seeking out enemy IADS targets of opportunity required flexibility, aircraft assigned to lane SEAD missions typically carried, in addition to their standard HARMs, GBU-31 JDAMs and CBU-103 wind-corrected munitions dispenser (or WCMD, pronounced “wick-mid”) canisters for potential pop-up hard-kill opportunities. During the campaign’s first five days, the HARM was used almost exclusively in its preemptive targeting mode because pilots flying the SEAD missions had no way of knowing what tactics the Iraqi SAM operators might attempt or which enemy threat systems might suddenly come up and start emitting—although, as one F-16CJ pilot noted, “the Iraqis knew for sure that if they came on the air, they were going to get a face full of HARM.”117 SEAD sorties typically lasted six to nine hours, with the longest ones continuing up to twelve hours, during which time the pilot could anticipate as many as nine tanker hookups.

Allied strike aircraft kept up the pressure on Iraq’s IADS in the Super MEZ for three days. During that time General Moseley continued to limit offensive air operations to night missions flown solely by stealthy B-2s and F-117s (only twelve of the latter had deployed forward for the war) or to standoff missile attacks either from high altitude, such as conventional air-launched cruise missiles carried by B-52s, or from ship-launched TLAMs.118 He directed a “staggering” of alternating waves of TLAM and manned aircraft attacks so that the enemy’s air raid alarms would be going off constantly.119 Only when Iraq’s air defenses in the Baghdad area were assessed without question to be down for the count did the CAOC begin operating nonstealthy aircraft throughout Iraqi airspace during daylight hours.120 It was only during the first week of the campaign that allied fighter aircrews operating in the relatively safe altitude regime above 20,000 feet repeatedly encountered heavy, if ineffective, Iraqi AAA fire.121 The commander of CVW-14, who led the opening-night strike package, recalled that “the Iraqi defenses were spectacular but ineffective. None of the SAMs were guiding, no one had any indication of being illuminated by fire control or target track radars, and the vast majority of the fireworks were in front of and mostly below us. Still, co-altitude AAA bursts and SAM trajectories rising through our altitude kept our jets in constant maneuver and our eyes out of the cockpit for the entire attack.”122

An F-16CJ pilot who was supporting a night F-117 strike near the heart of the Super MEZ recounted his tense experience while conducting such operations:

It was my first ride in country, and I had no idea. We had the Navy guys, who also wanted to go downtown, on our assigned tanker, and they wouldn’t let us get gas. . . . We all had HARMs, eight in total, and we didn’t know if the Iraqis were going to turn on their radars or not, so we were going to be firing preemptive shots. [W]e only got about 2,000 lb of gas each [from the tanker], meaning that our external tanks were still dry and that we had only our internal fuel to rely on. We turned off all our lights and pressed downtown in an offset container [box formation] in full afterburner. I was on NVGs, and all I could see were three big afterburner plumes racing downtown. Flying at 30,000 feet and Mach 1.2, I wanted to know what the guys in the AWACS must have been thinking. It was full on. I was a little light on gas, so I kept creeping up on everyone else, trying to find the right afterburner setting to keep in position. We got to about two minutes from Baghdad, and we knew that the F-117s should be just about to reach downtown. In plain English, we worked our target sorting—“I’ll take this one, you take that one”—and I was ready to shoot. I didn’t want to shoot first, though, as I wasn’t keen to be the one who screwed everything up! I was waiting and waiting, and nothing happened. Then there was this big freakin’ freight train of a missile whooshing right next to my canopy. You could smell the burnt powder of the rocket motor. What I didn’t realize was that it wouldn’t go high straight away. Instead, it was heading straight for [my flight leader and his wingman]. I was scared stiff until the missile eventually climbed and did its thing. . . .

We were still over the Mach [the speed of sound], and there was all this stuff coming up from the city. I was thinking to myself, “It’s going to be the one you don’t see that gets you.” My head was now literally looking everywhere in the sky and on the ground. In fact, I don’t think I was actually looking at anything, because my head was moving so fast. We finally shot our second missiles, and then we realized we had used up a lot of gas. We were right over the Super MEZ, and we turned around nice and slowly and went looking for a tanker. At this time, the tankers were still over Saudi Arabia, but we eventually found a guy who flew into Iraq with all his lights on, blinking away. Everyone else in Iraq must also have seen him, and then [my wingman] overshot him! We asked if he’d make another turn north, and he told us that he’d do it, but that it would be better for him if he headed south, as he was already over Iraq! I [finally] hooked up with only 800 lb of gas remaining. That’s about five minutes’ flying time, and we were still about an hour away from [our home base].123

The four F-16CJs took turns taking fuel from the tanker until each had enough to make it home.

Also in connection with the counter-IADS effort, several BQM-34 Firebee drones equipped with chaff dispensers and launched from airborne DC-130s were used as decoys to draw Iraqi SAM and AAA fire. Two Predator UAVs at the end of their service life (characterized by their operators as “chum”) were likewise pressed into service. These Predators, the oldest in the Air Force’s inventory, were stripped of their sensors and weapons and launched on missions that lasted between twenty-four and thirty-six hours to try to provoke a response from Iraqi air defenses and expose any remaining pockets of potential threats. The fact that the Predators survived as long as they did in the still-defended Super MEZ before running out of fuel was yet another testament to the intimidation effect that the coalition’s SEAD capabilities had on Iraq’s SAM operators in the Baghdad region.124

Leadership and Other Strategic Attacks