Preface

We hope this book never becomes an epitaph for what once was. Ohio is incredibly rich in biodiversity, possibly more so than any other midwestern state. But in the course of assembling a documentary book like this one, it’s impossible not to think about what we’ve lost. Some three hundred years ago the first European settlers stepped into the Ohio country, and it’s been nonstop development ever since.

Once, unchecked exploitation of our natural landscape was understandable, if not excusable. To the first pioneers, Ohio must have seemed like a land of inexhaustible bounty. But it isn’t, and that fact has been indisputably driven home.

The Buckeye State has lost over 90 percent of its original wetlands—second only to California amongst the fifty states. Wetlands (such as bogs, fens, and wet prairie) that are now great rarities once blanketed large expanses. Much of what is now Buckeye Lake in Licking County was a massive cranberry bog. The 427 acres of Cedar Bog are all that remain of an approximately seven-thousand-acre cedar fen. Grand Lake St. Marys in Auglaize and Mercer counties, the largest man-made lake in the world when it was built, flooded what must have been a spectacular wet prairie. The Great Black Swamp of northwest Ohio has been drained and cropped. Attendant with these losses has been a great diminishment of wetland flora and fauna.

Unimaginable schools of fishes choked pristine Ohio streams in John James Audubon’s time. Witness this 1848 account by Samuel Prescott Hildreth, one of the first settlers to describe the natural history of the Ohio River Valley: “[Streams] were filled with delicious fish in such abundance, that at certain times of the year, the smaller tributaries might be said to have been alive with them.” Of the 166 species of fishes documented in Ohio, seven species have vanished. Once, our lands were cloaked in dense old-growth timber that covered 95 percent of the state. Today, only a few small bits of ancient forest remain. Elk, American bison, cougar, gray wolf, and American marten all roamed our primeval landscape.

Flocks of wild parrots once plundered fruit from Ohio trees. Carolina parakeets, gorgeously colored in green, yellow, and red, were the only northern parrot. The last were seen in Ohio in 1862, and they went extinct by the early 1900s. Forests of virgin timber teemed with indescribably huge flocks of passenger pigeons; populations numbered in the billions. No one who witnessed these hordes, which might take days to pass a single point and break limbs off trees with the weight of roosting birds, would have predicted they would be extinct by 1914.

What wasn’t forest was mostly prairie—about fifteen hundred square miles of it. Stands of big bluestem and Indian grass stretched to the horizon, creating grassy seas that were a daunting sight to westward traveling settlers. In 1837 a man named Deere released a new invention, the chisel plow. Our oceans of prairie grasses and wildflowers were quickly converted to the modern prairie—corn, soybeans, and wheat. Today, less than 1 percent of original prairie survives.

Of the more than eighteen hundred species of native plants thus far documented in Ohio, 601 are listed as endangered, threatened, or potentially threatened—one-third of our flora. Statistics are similar for most animals. Our freshwater mussels have been especially hardhit. Degradation of water quality has led to the extirpation of nearly 20 percent of our original species. Of the remainder, over half are now state-listed. No one has a handle on many insect families and what losses may have occurred in those groups. There just hasn’t been time to study them thoroughly.

Loss of even a single organism can have impacts that ripple through entire ecosystems. Sometimes the effects are immediate and obvious; other times a species’s disappearance may not be noticed. In the words of conservationist Aldo Leopold, “To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.”

Ohio is a medium-sized state—the thirty-fifth largest of the fifty—covering about forty-four thousand square miles. A wealth of biodiversity fills our landscape with influences from western prairies, northern bogs, Appalachian mountains, and the mighty Mississippi River via its major tributary, the Ohio River.

Listed below are species totals for most major groups of Ohio organisms:

MOTHS—2,500 (estimated)

VASCULAR PLANTS—Approximately 1,800 native species

SPIDERS—580+

BIRDS—418

MOSSES—411

LICHENS—223 (not including 204 crustose lichens, which are not well known, and many remain to be found)

DRAGONFLIES—164

BUTTERFLIES—135

FISHES—134

FRESHWATER MUSSELS—98

MAMMALS—51

AMPHIBIANS—34

REPTILES—32

OTHER INSECTS (countless thousands; no one knows)

Poisonous Flora and Fauna: A common misconception is that poison oak occurs in Ohio. It does not; that species is southern and comes no closer than northern Virginia. Poison sumac is in Ohio, but is rare and local, confined largely to bogs and fens. Poison ivy is abundant and found in every county.

There are three species of venomous snakes in Ohio: copperhead, massasauga rattlesnake, and timber rattlesnake. Only the copperhead is fairly wide-ranging and somewhat common; it is found throughout the unglaciated Appalachian Plateaus and sparingly elsewhere in southern Ohio. The other two snakes are quite rare and local and discussed later in this book. Cottonmouths (sometimes called water moccasins) are often mistakenly attributed to Ohio. This southern species ranges no closer than southwestern Kentucky, and all Ohio reports are misidentifications.

Two well-known spider groups are found in Ohio that can inflict unpleasant bites: recluses and widows. Two species of recluses are known: brown and Mediterranean. Neither is thought to be native nor likely to be encountered. Typically they are found in buildings and probably can’t survive Ohio’s winters outside. Black and northern widows are found sporadically statewide but are generally rare. Females bite, and the effects can be nasty. Widows normally live in wood piles, rocky debris, under logs, and similar haunts. Exercising common sense, such as not reaching into crannies sight unseen, will probably eliminate most risk of spider bites.

PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS AND ORIGINAL VEGETATION OF OHIO

Sites in this book are divided by the five physiographic regions that occur in Ohio. Each has a unique character in regard to geology and plant communities. The map is courtesy of the Ohio Division of Geological Survey.

Vegetation as it looked prior to European settlement. Map by Robert B. Gordon, 1966. Courtesy of the Ohio Biological Survey.

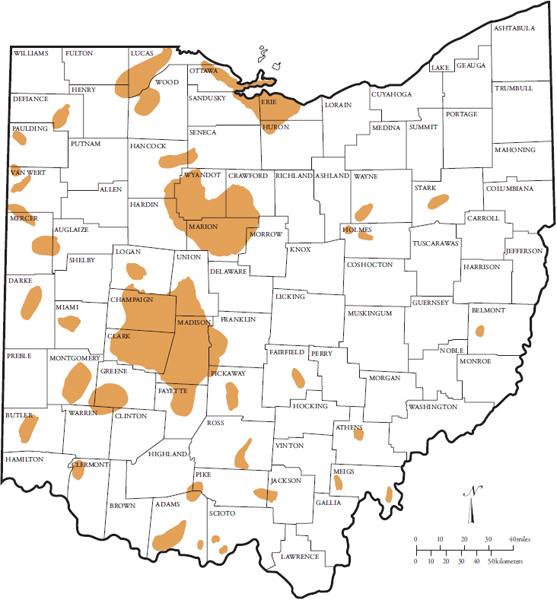

Approximate extent of Ohio’s original prairie prior to European settlement. Map created courtesy of Lisa Van Doren, Ohio Division of Geological Survey.

Forests: The largest contiguous forested tracts are in southeastern Ohio hill country. Dry ridges feature oak and hickory, while stream bottoms and lower slopes support mesophytic species such as tulip tree and green ash. The most extensive forests remain in this region, as the hilly topography is not generally conducive to farming or other large-scale development.

Glaciated regions of the state are forested with oak-hickory on well-drained sites, ranging to elm-ash swamps on poorly drained lands. Most forests in glaciated Ohio have been cut and converted to croplands or have been urbanized. Hardly any woods of substance remain in some western counties where agriculture dominates. The once vast Great Black Swamp that covered the northwestern corner of the state has been completely drained and cut over.

Prairie: Approximately four to eight thousand years ago, Ohio’s climate was much hotter and drier—an age known as the Xerothermic period. These conditions discouraged trees and encouraged eastward expansion of prairies from the Great Plains. At the time of European settlement, an estimated fifteen hundred square miles of prairie was present. Scattered pockets still occur well to the east of traditionally delineated prairie regions, such as in Athens and Holmes counties.

Most prairies occurred in large, contiguous regions such as the Darby Plains west of Columbus, the Pickaway Plains south of Circleville, and the Sandusky Plains near Marion. After machinery was invented that could cut thick prairie sod, this habitat soon vanished as settlers realized that lush crops could be grown in the rich soil. Today, less than 1 percent of our original prairie remains. The prairies of the Bluegrass Region, which encompass parts of Adams, Highland, and Pike counties, predate the Wisconsin glacier and are much older than other Ohio prairies. These small prairie openings harbor a number of globally rare plants.

Wetlands: At the time of settlement, vast expanses of wetlands covered Ohio. Now Ohio has the dubious distinction of being second only to California in wetland acreage lost—over 90 percent. The most common type was and is swamps, which are wooded wetlands. The largest tract of Ohio swampland was the Great Black Swamp of northwestern Ohio, but much of the glaciated Till Plains was also swamp forest.

Marshes are wetlands dominated by herbaceous plants such as bulrushes and cattails, and the biggest remaining marshlands are the wetlands buffering western Lake Erie. Our second most frequent wetland type, marshes are still commonly found throughout Ohio.

Much of our former prairies were also wetlands, vegetated by specialized wetland prairie plants such as wheat sedge and prairie cord grass. Wet prairie verged into fens in the wettest, most alkaline areas. Fens are “sweet bogs,” wetlands fed by cool artesian groundwater and populated by distinct plant life restricted to fen habitats.

Bogs are glacial kettle lakes filled with acid-loving plants growing on a substrate of Sphagnum moss. This wetland type was never plentiful in Ohio, at least in the last several thousand years, and is mostly found in the northeastern corner of the state.

Unique among Ohio wetlands is Cedar Bog (pages 39–41), which is a white cedar–dominated wetland. This is a habitat normally found far to the north, and which probably never occurred elsewhere in Ohio, although Cedar Bog was far larger at one time.

Lake Erie: The second smallest of the Great Lakes buffers most of Ohio’s northern border and has a profound influence on our biodiversity. Lake Erie ecosystems support some of the most important migratory bird habitat in the Midwest and it is the most biologically rich of the five Great Lakes. Open lake waters attract masses of water birds and support world-class fisheries. Shoreline habitats are varied, from sand beaches to cliffs to marshes.

Oak Openings: The old beach ridges and dunes of preglacial Lake Warren, Lake Erie’s predecessor, cover about 130 square miles west of Toledo. Now found mostly in Lucas County, the Oak Openings originally covered three hundred square miles. Ohio’s greatest concentration of rare species occurs here.

Rivers: Ohio has over sixty thousand miles of streams, and they play a vital role in supporting our diverse flora and fauna. Our largest river is the Ohio, of which about 451 miles serve as the state’s southern border. Many species of animals and plants migrated northward into Ohio via this Mississippi River tributary, and a number of them occur no farther north. Large lock and dam projects designed to facilitate shipping have largely destroyed the natural character of the Ohio River.

The Teays River was a prehistoric drainage that flowed northward into Ohio from southern Appalachian regions up until about two million years ago. Over the Teays’ existence, numerous Appalachian plant species such as rhododendrons and magnolias migrated north along the river and can be found in southern Ohio to this day.

The Lake Erie drainage St. Marys River of western Ohio forms a natural connection with the Mississippi drainage Wabash River, and serves as a vital conduit for animals and plants to migrate between the drainages. Many species entered the Great Lakes drainage through this natural portal. Big Lake Erie tributaries such as the Maumee, Sandusky, and Grand rivers provide critical spawning habitat for lake fishes such as walleye.

Ohio founded the nation’s first scenic rivers program in 1968 and has long been at the forefront of river conservation. To date, 754 river miles on parts of twenty-three streams have been designated as scenic rivers. This program is administered by the Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves.

SELECTION OF SITES AND OTHER NOTES

Few seasoned Ohio naturalists would dispute that the places included in this book belong in a listing of our best remaining natural areas. There are plenty of other worthy candidates, though. Space precludes detailing them all. We wanted to feature areas that exhibit the best attributes of the habitat or ecosystem in question. The one exception is Tri-Valley Wildlife Area, which is the product of strip mine reclamation and is now a mammoth artificial grassland. After debate we decided that its importance to grassland birds warrants its inclusion. Tri-Valley also represents a habitat of which as many as 250,000 acres are now found in southeastern Ohio, with important ramifications for bird conservation.

All of the areas in this book are available for public access, although permits or special arrangements may have to be made for some. There are many other outstanding natural areas that are privately held, and we didn’t want to get into the complexities of publicizing such sites.

Fifteen agencies and organizations own the sites discussed in this book. Collectively, they protect examples of every major habitat type in Ohio and nearly 100 percent of our flora and fauna.

In the main text, only common or English names of plants and animals are used. Fortunately, animals have increasingly had their English names standardized, and there is less ambiguity when referring to them without using a scientific name. Not so with plants, and botanists will often be puzzled if no scientific name is provided, particularly for groups like grasses and sedges. Because of the hundreds of species of flora and fauna mentioned in the text, we wanted to avoid cluttering it by pairing scientific names with every organism mentioned. A separate index lists all animals and plants alphabetically by English name, along with their scientific name.

Finally, we encourage you to visit these places and view the greatest natural resources that Ohio has to offer.