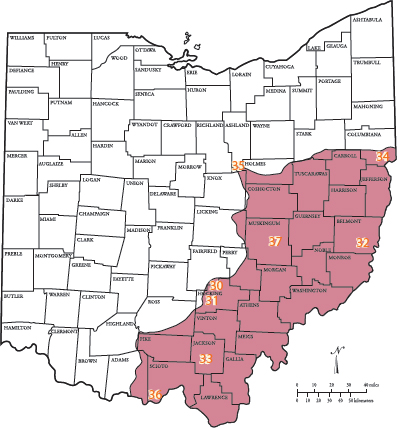

Appalachian

Plateaus

Clear Creek Metropark (30) • Conkles Hollow State Nature Preserve (31) • Dysart Woods (32) • Lake Katharine State Nature Preserve (33) • Little Beaver Creek (34) • Mohican State Forest (35) • Shawnee State Forest (36) • Tri-Valley Wildlife Area (37)

Beautiful rose-breasted grosbeaks are common breeding species of riparian corridors. Nesting in the midcanopy, their rich robinlike song can be heard up and down the creek.

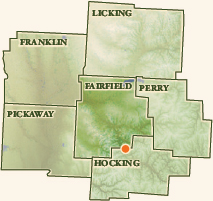

Clear Creek Metropark

ACREAGE: 5,252

OWNERSHIP: Columbus and Franklin County Metroparks

ACCESS: Open during posted hours; good network of trails

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.metroparks.net/

http://www.ohiodnr.com/dnap/location/clearcreek.htm

http://www.ohiobirds.org/birdingsites/showsite.php?Site_ID=46

Plant communities from every compass point converge at Clear Creek. This impressive valley was scoured through highly erosive Mississippian-age sandstone over millennia by nature’s great mason, water. Located on the northern fringe of the Hocking Hills and only forty minutes from Columbus, Clear Creek is one of the most beautiful and diverse ecosystems in Ohio.

Northern influences are obvious. A boreal conifer, Eastern hemlock, blankets the north-facing slopes of Clear Creek, their boughs casting deep shade over the forest floor. Interspersed is yellow birch, a tree of Appalachian coves and northern woods, with its flaky bark and twigs that taste of wintergreen. Disjunct relicts, a number of species of boreal birds rarely found this far south nest in the valley. Beautiful flutelike melodies of hermit thrushes join the songs of other northerners, such as blue-headed vireo and Canada warbler. A stone’s toss away, the south-facing stream slopes provide a world of contrast to dense hemlock groves. Deciduous forests dominate on these sunnier slopes, characterized by trees like white and red oak, shagbark hickory, tulip tree, and sourwood. The breeding birds differ radically, too. Southerners like worm-eating and Kentucky warblers, and occasionally summer tanager, are found. Black vultures, near their northern limits at Clear Creek, are common—one of few Ohio strongholds.

Appalachian flora, at its western limits in the valley, is conspicuous. Thickets of mountain laurel crest rocky summits, and a few patches of rare great rhododendron grow on steep slopes. Sourwood and chestnut oak, Appalachian trees found no farther west in this region, are common on xeric ridges. A treat is finding patches of pink lady’s-slipper in the upland woods.

Most yellow-throated warblers in Ohio are associated with sycamore trees; indeed, the bird was once known as sycamore warbler. One of our first neotropical species to return, its clear cascading notes can be heard by late March.

Black-and-white warblers forage along the trunks and limbs of trees in the manner of a nuthatch or brown creeper, aided by a hind claw much longer than that of other warblers. Interestingly for such an arboreal species, they place their nests on the ground—one of nine of the twenty-five regularly nesting Ohio warblers to do so.

Streamside habitats feature ghostly white sycamore trees, often underlain by thick carpets of scouring-rush, an odd reedlike fern and one of our most primitive plants. Its relative the ostrich fern, almost unknown in central Ohio, also grows sparingly on stream terraces.

Sandstone outcrops abound, and these rocky promontories support interesting plants like wild columbine, rock polypody, and early saxifrage. A can’t-miss rock is Leaning Lena, a sandstone slump block that tumbled from the cliffs above long ago. Clear Creek Road passes underneath the wildly tilted cabin-sized monolith, inspiring passersby to hope it doesn’t choose that moment to complete its fall. Similar sandstone blocks litter cliff bases throughout the valley; the results of water erosion of softer underlying rocks.

Clear Creek Valley has been studied by naturalists for many decades. Legendary biologist Edward S. Thomas had a cabin in a side valley he dubbed Neotoma, named for the genus of the Allegheny wood rat. That rare mammal no longer occurs, but plenty of other biodiversity does. To date, about eight hundred species of plants have been documented in Clear Creek’s varied habitats. Over 110 species of birds nest in and around the valley, including several of Ohio’s rarest breeding species.

First-time visitors would do well to hike the Hemlock Trail, which offers a taste of many of the valley’s habitats. A trip to Clear Creek won’t disappoint, at any season.

The ethereal song of the hermit thrush is an unforgettable melody. Along with a small suite of species that includes Canada warbler and winter wren, the thrush is a boreal disjunct.

Conkles Hollow State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 87 acres

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Open during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/location/conkles_hollow.html

http://www.ohiobirds.org/birdingsites/showsite.php?Site_ID=62

In Hocking Hills, a region renowned for spectacular scenery, Conkles Hollow stands out. Countless thousands of visitors have hiked the gorge, awed by massive sandstone formations, lush beds of ferns, and thick stands of hemlock, all conspiring to create the illusion of being in Canada’s north woods.

The story of the gorge dates back about 360 million years ago, when Mississippian shales that comprise much of the Hocking Hills began to form. Numerous geologic upheavals in the intervening millions of years formed the rugged terrain of this region, and nonstop forces of water and gravity carved impressive valleys in softer, more permeable rock strata.

Plant life in the box canyonlike gorge is totally different than along the summits above. Perpetual shade rules in the valley, cast by towering Eastern hemlock trees. The rich humus of stream terraces is lush with ferns, most commonly the fancy fern. It forms luxuriant clumps in profusion and is one of the gorge’s most conspicuous botanical features. Other plants of moist shady habitats are easily found, including miterwort, foamflower, and wild stonecrop, the last our only native Sedum.

Sharp ears will soon detect summer bird songs not often heard in Ohio. The boreal nature of the hemlock forest attracts many species normally breeding far to the north, such as hermit thrush, black-throated green, Blackburnian, Canada, and magnolia warblers, and blue-headed vireo.

Venture up steep trails to the summits of Conkles Hollow and a completely different woodland awaits. Dry oak-hickory forests rim the canyon below. Barren rocky precipices along the summits host heaths such as deerberry, huckleberry, and our only tree in the family, sourwood. The other Ohio habitat in which heaths dominate are peat bogs. Dry, acidic ridges of the unglaciated hill country are their ecological counterparts.

A little-studied facet of Ohio’s natural history is lichens, which abound at Conkles Hollow. Lichens are the symbiotic pairing of a moss and a fungus, and oak trunks and sandstone rocks provide excellent substrates for their growth. Several dozen species occur in and along the gorge. The rarest may be the distinctive pink-dot lichen, found in only a few other locales. Easily dismissed as crusts on rocks or trees, lichens serve several important ecological roles. They begin the long process of rock erosion by collecting moisture and stimulating stress fractures. Insects such as lacewing larvae hide among them, and gnatcatchers and hummingbirds shingle their nests with larger species like greenshield lichen. Lichens also are sensitive air-quality indicators, among the first groups of organisms to vanish if pollution becomes oppressive. American Electric Power, the energy giant, has long used lichens as bio-indicators to gauge plant emissions.

One of Ohio’s most inspiring vistas is the view from the upper-rim trail overlooking Conkles Hollow. The tallest cliff in the state, a vertical sandstone face extends nearly two hundred feet above the valley. In autumn, a tapestry of oak, hickory, sourwood, maple, tulip tree, and other trees tint the forest in rich hues of red, yellow, and orange.

Hooded warblers are denizens of the dense, shady forest understory. As an adaptation to the gloom of their heavily forested haunts, hooded warblers have evolved the largest eyes of any warbler species.

Beautiful Blackburnian warblers are one of Ohio’s rarest breeding species. Near the southern edge of their nesting range in Ohio, they occupy only the highest quality hemlock gorges.

Interesting flora aside, the climb to the top is justified by the sensational views. The tallest cliffs in the state are here, and vistas over extensive surrounding forests are unsurpassed in the region.

There are about twenty-five hundred species of moths in Ohio. One of our most beautiful species is the luna moth. The caterpillars feed mainly on cherry, hickory, and walnut.

Dysart Woods

ACREAGE: 50

OWNERSHIP: Ohio University

ACCESS: Open to the public any time

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.plantbio.ohiou.edu/epb/facility/dysart/dysart.htm

Dysart Woods is a museum piece of giant timber. This magnificent woodlot offers a glimpse back to the presettlement wilds of southeastern Ohio. Some of the largest trees left in the state occur here. Massive red and white oaks and tulip trees push 140 feet into the sky and attain diameters exceeding four feet. This small tract of woodland is perhaps the least disturbed of any forest remaining in the state.

Visitors to Dysart will be instilled with a sense of awe. Trees that weigh many tons and rise to the height of a fourteen-story skyscraper are the eastern counterparts of western redwoods and almost defy belief. It’s a testimony to human ingenuity and energy that we managed to clear the landscape of woodland behemoths so rapidly after settlement.

Huge trees create multidimensional habitats on a vertical plane. Their roots play host to specialized fungi and odd hemiparasitic plants like beech-drops and squaw-root, as well as bind the soil and prevent erosion. Massive trunks provide substrates for myriad arboreal lichens, mosses, and fungi, some of which provide habitat for insects, material for bird nests, and, in the case of lichens, excellent barometers of air quality.

The crowns of such mammoths have worlds of their own. Many species of birds, such as cerulean warblers and pileated woodpeckers, require mature timber. Untold varieties of Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) live and forage in the leaves. One rare butterfly, the early hairstreak, may be more common than we think. Apparently it is reluctant to leave sky-high leafy canopies. Massive American beech and oaks provide bumper crops of mast, which in turn fuel many species of birds and mammals—everything from gray squirrels to wild turkeys.

A tree-top dweller, the cerulean warbler sings a buzzy, spirally ascending song. Ohio supports some of the best remaining breeding populations. Cutting of our eastern deciduous forest has eliminated much breeding habitat for this imperiled species.

Dysart Woods is renowned for containing some of the largest trees in Ohio. These giant red oaks are several hundred years old. Primeval forests such as Dysart can be counted on one hand. Here, a visitor can get a taste for what Ohio’s early pioneers would have seen.

Emitting a loud, explosive song that sounds like peet-sa, the Acadian flycatcher is a common mid-canopy breeding bird of rich deciduous eastern forests.

Sylvan colossi as are found at Dysart once covered over 90 percent of Ohio. Now, only an almost immeasurably small fraction of a percent of old-growth woodland remains. One would think that we would protect these remnants from any intrusion, without debate or caveat. Unfortunately, as is often the case in southeastern Ohio, property owners of surface lands don’t own subsurface mineral rights. The owners of the latter are free to access their holdings, which in the case of Dysart Woods involve subterranean coal seams.

After a prolonged legal battle, environmentalists lost a fight to prevent a coal company from boring under Dysart to extract the combustible mineral. Claims have been made that a technique known as longwall mining is noninvasive and won’t harm the forest above. Hopefully that’s true, but only time will tell.

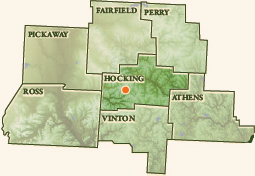

Lake Katharine State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 2,000

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/location/lake_katharine/tabid/904/

Default.aspx

Knobs and outcrops of Sharon conglomerate sandstone form the substrate at Lake Katharine and make for interesting rock-watching. Trailside cliffs offer educational portals into Ohio’s geological past. Sandstone walls often exhibit honeycombed erosion patterns, sedimentary stratification, and recessed rock shelters. Sharon conglomerate formed during the Pennsylvanian subperiod of the Paleozoic era, some three hundred million years past. At that time, vast swampy forests covered the land, and evidence of this past is obvious in the Sharon conglomerate. Various fossilized clams, snails, pebbles, and shells embedded in the rock provide proof that this high and dry land was once wetland.

An excellent trail system offers access to the varied habitats of Lake Katharine. Plant communities change markedly from bone-dry ridgetops to moist creek bottoms. Atop sandstone crests are three of Ohio’s four native pines: pitch, shortleaf, and Virginia. Large conifers support breeding pine warblers, a species that must have mature pine stands. The arid, acidic soils of these sandstone ridges are similar to peat bogs floristically, if not in appearance. Heaths dominate, among them several species of low-growing blueberry, wintergreen, trailing arbutus, and sourwood.

Barren cliff faces provide fascinating botanizing. Many species of ferns colonize fissures and ledges of rock formations, including diminutive lobed spleenwort and mountain spleenwort. Sometimes a sharp eye can spot Trudell’s spleenwort, a cross between the two, and one of twenty-one hybrid ferns documented in Ohio. Far more conspicuous are bright red flowers of round-leaved catchfly, which grow in loose sand at cliff bases.

Tangles of mountain laurel often festoon the bluffs of sandstone outcrops on southern Ohio ridges. This shrub is a host plant for the rare brown elfin butterfly.

Seeing a colony of exquisite pink lady’s-slippers is an unforgettable spectacle. Like many orchids, lady’s-slippers require specialized soil conditions involving a poorly understood relationship with mycorrhizal fungi.

Floodplain terraces along Salt Creek and its tributaries have much richer soil than the highlands, and plant life is very different. Thick stands of pawpaw form mini-jungles along streams and produce vigorous populations of zebra swallowtails. This striking butterfly depends on pawpaw as a host plant. Towering sycamores, green ash, and tulip trees form one-hundred-foot-high canopies that shelter riparian birds such as Northern parula, yellow-throated warbler, Baltimore oriole, and cedar waxwing. About half of Ohio’s 180 nesting bird species breed at Lake Katharine.

The most significant feature of the preserve may be its magnolias. Four species of these mostly southern trees occur in Ohio, and only the tulip tree is common and widespread. Rare umbrella magnolias grow on stream terraces, startling visitors with their massive leaves. Jackson County is as far north as they get. Even more amazing, and much rarer, are endangered bigleaf magnolias. The leaves of this small tree can eclipse two feet in length and create an almost jarring tropical flavor in otherwise typical Appalachian woodlands. Bigleafs are only known from Lake Katharine and the immediate vicinity.

One of five native lizards in Ohio, fence lizards are lightning fast and are most often heard as they scuttle through dry leaf litter. Perseverance will reward an observer, and with patience Eastern fence lizards can be closely approached and admired.

Rough green snakes are easily overlooked, as they are arboreal and spend much time hunting insects in the branches of shrubs and trees. This species is confined to Ohio’s southernmost counties.

A long-dead river known as the Teays delivered magnolias and other southern flora to Lake Katharine. This stream flowed during the Tertiary period, which commenced sixty-five million years ago. Glaciation obliterated the Teays River about two million years ago. The Teays had its headwaters near what is now the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina and ran north, entering Ohio near Portsmouth and exiting near present-day Grand Lake St. Marys. Over its eons of existence, Appalachian flora—rhododendrons, magnolias, and many others—migrated northward along the Teays. Some of these plants—the northernmost outliers of their species—still remain. In a sense they were marooned by the prehistoric river.

With two-foot leaves, the umbrella magnolia nearly sets the record for the largest simple leaves of any Ohio plant. Not a large tree, it rarely reaches a height of fifty feet.

Little Beaver Creek

ACREAGE: ODNR lands total nearly 3,200 acres

OWNERSHIP: Miscellaneous

ACCESS: Best access via state park lands and state nature preserve. Sheepskin Hollow State Nature Preserve; Beaver Creek State Park

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.ohiodnr.com/parks/parks/beaverck.htm

Slicing through the western Appalachian foothills of Columbiana County, Little Beaver Creek offers a taste of presettlement Ohio. Few Ohio streams are as wild in character, a fact supported by its status as a State and National Wild River.

Little Beaver’s rushing waters cascade down a rapid forty-five-foot drop at Purgatory Hollow Falls, carving through Lower Freeport sandstone formations. Elsewhere in Beaver Creek State Park, promontories of sandstone jut above the valley, providing sensational scenery.

Protecting forests is integral to protecting rivers; buffering woodlands prevent silt and other pollutants from entering the stream. And forests aplenty are along the course of Little Beaver Creek, keeping its waters pristine. There is an abundance of life, both aquatic and terrestrial. Anglers enjoy smallmouth bass fishing, and birders will be dazzled by an incredible diversity of avifauna.

The melodies of feathered songsters fill summer mornings: species such as black-and-white warbler, scarlet tanager, and wood thrush are common. All told, some 120 species have been documented breeding along Little Beaver. Many of them have come from far-flung haunts—the three listed above winter in Central and South America and are merely temporary visitors to our latitude.

One of the most picturesque streams in Ohio, Little Beaver is also one of the most pristine. Large forested buffers, as seen along the North Fork of Little Beaver Creek in this photo, are vital to the protection of the stream. Riparian woodlands play host to many specialized terrestrial plants and animals, and the lush cover serves as a buffer filter against contaminants. By reducing sediment and other contaminants that would otherwise enter the stream, forests ensure that water quality remains high, thus protecting the aquatic organisms.

In late summer, wildflowers bloom in profusion on the banks of Beaver Creek. Unlike diminutive spring flora, autumnal herbs reach for the sky, with some species like tall iron-weed and wingstem growing head high.

Flora is spectacular, especially in May. Some upland oak–dominated ridges support colonies of pink lady’s-slippers, an extraordinary orchid whose looks rival any tropical species. Rich slopes are carpeted with Ohio’s official wildflower, large-flowered trillium, and stream terraces host blankets of gorgeous blue-eyed Marys. Accomplished botanists have fun seeking rarities like speckled wood-lily, mountain-fringe, and rock skullcap.

An important modern-day discovery was documentation of common mergansers nesting along Little Beaver—the first Ohio record. Breeding had been suspected for several years, but confirmation came in 2006 when an adult was found with a brood of young chicks. These large fish-eating ducks require clear, swift rivers with ample forests, and their presence along Little Beaver is a symbol of the wildness of this river.

The spritely Northern parula is our smallest warbler, weighing but eight grams—same as a fifty-cent piece—and measuring 4½ inches in length. A neotropical migrant, parulas winter in the Caribbean and in Central America. Protecting mature riparian habitats such as are found along Little Beaver is imperative to conserving this tiny but amazing bird.

The hellbender is our largest salamander. Big ones can be nearly two feet in length. Little Beaver Creek harbors one of Ohio’s few remaining populations of this endangered species.

Mohican State Forest

ACREAGE: 5,664 (4,525 state forest; 1,110 state park; 29 state nature preserve)

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Divisions of Forestry, Parks, and Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.ohiodnr.com/forests/mohican/tabid/5160/Default.aspx

http://www.ohiodnr.com/parks/mohican/tabid/769/Default.aspx

http://www.ohiodnr.com/dnap/location/clear_fork/tabid/928/Default.aspx

Clear Fork Gorge is the centerpiece of Mohican, a three-hundred-foot-deep gash carved through Mississippian-age sandstones. Massive ice sheets of the Wisconsin glacier skidded to a stop just a mile northward and glacial meltwaters flumed through this valley, excavating the steep-sided canyon. The two sides of the gorge differ dramatically. North-facing slopes are shaded and much cooler, with thick stands of hemlock shrouding the steep hills. Other botanical northerners include Canada yew, yellow birch, and white pine. Craggy sandstone cliffs and outcrops are dominant features, and fissures vent fifty-six-degree air from subterranean pockets, further chilling the valley. It might be ten or more degrees cooler in the valley’s depths than in the uplands on a hot summer day. These cool valleys were given the name Neotomas.

Mohican ranks tenth largest among Ohio’s twenty state forests, but in spite of its relatively small size it may harbor more breeding bird diversity than any other Ohio woodland. The forest is a rich tapestry of plant communities, including mature hemlock-covered slopes. Although only five thousand acres, Mohican State Forest supports over one hundred species of breeding birds.

Deep hemlock forests on the gorge’s north slope support some of Ohio’s rarest breeding birds. Fiery-throated Blackburnian warblers deliver high-pitched songs, inaudible to those of less-than-perfect hearing, and Canada warblers shout their short explosive warbles. Eclipsing all in sheer melodic descant are the speckled, shy, and rarely seen hermit thrushes, whose rich tunes are among nature’s most extraordinary lyrics. All of these birds are abundant nesters in the expanse of boreal forest that sweeps across northern North America—a forest ecosystem greater in scope than the jungles of the Amazonian basin. At latitudes this far south, they are rare disjuncts confined to remnant boreal forests like Mohican.

South-facing hillsides of the Clear Fork gorge are warmer and dominated by mixed-mesophytic forests. Stream terraces support massive sycamores, and as one advances upslope, trees shift between tulip tree, white ash, red oak, white oak, hickory, and others. In contrast to the northerners on the opposite slope, birds on south slopes include southerners near their northern limits. Dry monotonic trills of worm-eating warblers mix with the bold ringing churee churee churee of Kentucky warblers. Inquisitive Carolina chickadees search boughs and cavities for prey, emitting four-noted fee-bee fee-bay songs. Mohican is their northern boundary—black-capped chickadees occupy the lands beyond.

Common migrants, scores of magnolia warblers can be seen on a good spring or fall migration day. Not so for breeders—they are at the southern end of their boreal breeding range in Ohio and only a few isolated populations occur.

A little-seen aspect of Mohican biodiversity is bats. These nocturnal mammals are abundant in the gorge, holing up during daylight hours under exfoliating tree bark and in rocky crevasses. At night, they emerge to hunt nighttime insects over the waters of the Mohican River. At least six of Ohio’s eleven bat species have been found in the Clear Fork gorge. A common one is the Northern myotis. Possessed of Vulcanlike ears à la Mr. Spock, these bats often glean insects from foliage rather than engaging in the fabulous aerial pursuits of their counterparts. Local researchers have been tagging bats in the gorge for years, and a Northern myotis recaptured in May 2007 had been tagged in July 2002. Extraordinary creatures, bats play vital roles in insect control and are an underappreciated constituency of Ohio’s natural diversity.

Because of its close proximity to major urban centers, Mohican is especially valuable to people wishing to see wild lands close at hand. This forest is an irreplaceable ecological treasure invaluable for education, research, conservation of species diversity, and enjoyment of the outdoors.

American redstarts forage actively in the forest understory. The brilliant flashes of orange displayed from their constantly flicking wings and tail serve to flush insects from the foliage.

An early spring migrant, the wheezy zee zee zee zoo zee song of the black-throated green warbler becomes a common sound by mid-April. While an abundant migrant, breeders are much scarcer and largely confined to our biggest and best hemlock gorges such as Mohican.

Mohican is one of the few Ohio regions in which white pine grows naturally. The trees pictured in this grove are over two hundred years old. The state champion is 153 feet tall and nearly nine feet in circumference at breast height.

Shawnee State Forest

ACREAGE: 65,000

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Forestry

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.ohiodnr.com/forests/shawnee/tabid/5166/Default.aspx

http://www.ohiodnr.com/parks/shawnee/tabid/788/Default.aspx

http://www.ohiobirds.org/birdingsites/showsite.php?Site_ID=16

Shawnee State Forest is Ohio’s greatest remaining wilderness. Seemingly endless woodlands stretch across jagged razorback ridges bisected with steep chasms bottomed with clear, rushing streams. Animals once common throughout the state and symbols of wild lands still occur here, such as bobcat, timber rattlesnake, and occasional black bears. Miles of sparsely traveled lanes traverse the woodlands, and cars are only seldom encountered.

Acquisition by the State of Ohio began in 1922, and Shawnee was a different place then. Many of the steep slopes had been cleared for small farms, and forests were grazed by farm animals. Lack of modern forestry practices caused severe erosion; many hillsides were devoid of timber, and chiseled gulches pocked barren hillsides. It’s hard to imagine such lunar landscapes when gazing on today’s Shawnee, carpeted with mature trees of many species filled with songs of woodland birds.

The botanical diversity of Shawnee is tremendous, possibly unrivaled elsewhere in Ohio. About one thousand species of native plants grow here, of the 1,800+ known statewide. The underlying geology strongly influences plant communities. Devonian- and Mississippianage bedrock form the mantle on which the forest sets, and high, dry ridges are acidic and shaley. Chestnut and scarlet oaks dominate and overgrow huckleberries and blueberries. As one moves downslope, tree associations progressively become more mesophytic, and tulip tree, sweet gum, and white basswood dominate stream terraces.

Our mightiest river, the Ohio, forms Shawnee’s southern boundary. The river valley has its own microclimate. Wintertime temperatures remain milder than over the hills just to the north. Formed approximately 120,000 years ago, the Ohio serves as a conduit for southern plants to migrate northward. Some plants reach their northern limits at Shawnee. Among them is American mistletoe, the same species we hang in doorways at Yule. Orbicular masses of this evergreen parasite festoon riverside American elms and silver maples.

In April, redbud and flowering dogwood blushes the woodland edges of Shawnee State Forest.

Occurring in remote woodlands, timber rattlesnakes are a true wilderness symbol. Shawnee harbors the state’s best populations.

Another stream, far older than the Ohio, made Shawnee a botanical treasure trove. The Teays River, which capitulated to glacial advances of Pleistocene ice sheets two million years ago, flowed north from the Carolinas and into Ohio at Portsmouth. Over eons it transported Appalachian plants along its channel, and some still occur here, botanical relicts of glacial history. Examples include golden-star, small-flowered scorpion-weed, gall-of-the-earth, wedge-leaved violet, Southern monkshood, and early stoneroot. All are state-endangered, and none are found elsewhere north of the Ohio River.

Obvious evidence of Appalachian links are rhododendrons and azaleas. In May, aromatic pink flowers ornament pinxter-flower azaleas, and great rhododendron is sparingly scattered. Another southerner, umbrella magnolia, unfurls giant two-foot leaves on shady stream terraces. Rarest of all is Appalachian spiraea, a colonial shrub with showy panicles of white blooms. This federally threatened plant grows on gravel bars in nearby Scioto Brush Creek.

One of twenty-one species of Ohio salamanders, the mud salamander is among the rarest. New populations have recently been discovered within its known range.

Zebra swallowtails swarm in spring at Shawnee. The larvae feed on abundant pawpaw.

Large numbers of worm-eating warblers find Shawnee’s ravines ideal for nesting. Shawnee is one of Ohio’s top birding areas.

The forest is an avian paradise. Staggering numbers of woodland breeders fill the air with a riot of song in spring and summer. Cerulean warblers, a declining neotropical species, are abundant. Their buzzy spiraling songs drift from oak canopies; they’re much more muted in Colombian and Venezuelan jungles where they winter. Woodpeckers abound; six species can be found nesting. Hairy and pileated woodpeckers are common; both require more extensive mature woods than do their brethren. Flycatchers of four species nest, including large, showy great crested flycatchers. Exhaling war-whoop wheeep calls, this cinnamon, yellow, and gray mid-canopy inhabitant is our only cavity-nesting flycatcher. Entrance holes are often adorned with a snakeskin.

Shawnee State Forest’s biological significance cannot be understated. Species richness is probably unparalleled north of the Ohio River. At least forty-eight state-listed rare plants grow, including many found nowhere else in Ohio. One of only two Ohio records of the federally threatened small whorled pogonia orchid was found in Shawnee. New botanical finds are routinely made. Clear brooks have threatened rosyside dace; rare tiger spiketail dragonflies patrol overhead. Reptiles abound: four species of lizards, seventeen of snakes, and five turtle species. Twenty-nine species of amphibians have so far been tallied as well as forty-four mammals. Several dozen butterfly species help pollinate the plants. Moth diversity? No one really knows how many might be here, and that’s true of most insect groups.

Birds really tie Shawnee to the global bio-economy. Over half of the state’s sixty-one species of breeding neotropical birds nest here. Yellow-throated warblers travel to Caribbean islands for the winter. Ruby-throated hummingbirds journey from Shawnee to Central America, a trip that includes five hundred nonstop miles across the Gulf of Mexico. In all, birds that nest in Shawnee will disperse to ancestral habitats in Mexico and in every country of the Caribbean, Central America, and South America. How we treat Ohio habitats has an impact far beyond our borders.

The entire golden-star population blooms within the space of a few early April days. It resembles the far commoner yellow trout-lily. The rarest lily in Ohio, it was discovered in the Rocky Fork drainage by Ohio botanist Emma Lucy Braun.

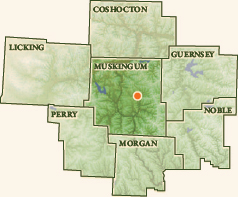

Tri-Valley Wildlife Area

ACREAGE: 16,200

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Wildlife

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.ohiodnr.com/Home/wild_resourcessubhomepage/

ildlifeAreaMapsRepository/tabid/10579/Default.aspx

http://www.ohiobirds.org/birdingsites/showsite.php?Site_ID=93

A visitor blindfolded and plunked down unawares in the midst of Tri-Valley might think he or she landed in Africa. This sprawling grassland resembles plains where zebra and rhino roam, quite unlike anything found naturally in Ohio.

And Tri-Valley is anything but natural, and thus a big departure from every other site included in this book. But it is worthy of inclusion, as through sheer serendipity this grassland and others like it have imperfectly duplicated Ohio’s former prairies, more than 99 percent of which have been destroyed. Along with the loss of native prairies came a great reduction in grassland birds that depended upon prairie landscapes.

The story of Tri-Valley is inextricably linked to coal. Massive subterranean seams of black gold underlay the hills of southeastern Ohio, and to extract it mining companies developed a technique called strip mining. Massive draglines were built to scoop away overlying topsoil, allowing the coal to be chiseled out and carted off. The downside was the destruction of hundreds of thousands of acres of fertile deciduous forest and their attendant biodiversity.

Many birders make pilgrimages to reclaimed mine sites like Tri-Valley to see this secretive, declining species. Ohio sites harbor some of the largest Henslow’s sparrow populations anywhere.

Formally dressed blackbirds, bobolinks are common breeders in the meadows at Tri-Valley.

Northern harriers are rare breeders in Ohio. Reclamation grasslands support some of the few nesting pairs of this state-endangered species.

The cheerily whistled bob-BOB-WHITE! was once a ubiquitous sound in Ohio’s countryside. As farming practices became less bird-friendly, suitable habitat for our only native quail steadily diminished. A reintroduction program at Tri-Valley by the Ohio Division of Wildlife has been successful, and quail are easily heard here.

Savannah sparrows are frequent nesters at sites such as Tri-Valley, where their insectlike tsee-tsayyy trill is a common sound.

In 1972, Ohio legislators enacted House Bill 521, requiring miners to rehabilitate the lunar landscapes caused by strip mining. Reclamation involved smoothing away jagged contours of the land, and planting the newly smoothed ground to grasses to stabilize soil. Perhaps a quarter million acres of reclamation lands now sprinkle southeastern Ohio. Virtually all grasses and other plants used in reclamation are non-native. Nonetheless, many species of birds that had declined due to prairie destruction and the loss of smaller, more ecofriendly farms flourished at Tri-Valley and similar sites.

Today, birders visiting Tri-Valley in summer will be dazzled by a medley of bobolinks, dickcissels, Eastern meadowlarks, grasshopper sparrows, and many more. This site and others like it now harbor Ohio’s largest and most significant concentrations of many grassland birds, including rare breeders such as the Northern harrier and short-eared owl.

Of particular interest to ornithologists is the mouselike, cryptic Henslow’s sparrow. This shy, retiring bird has suffered the greatest population decline of any eastern sparrow. They have taken to reclamation grasslands like Tri-Valley with a vengeance, and these areas now contain the largest Henslow’s sparrow colonies in Ohio.

Grasslands such as Tri-Valley become globally significant when one considers the bobolink, which sometimes nests here in large numbers. A colorful blackbird, bobolinks have a delightful song. Males, while on the wing, deliver a bubbly cacophony of gurgling whistles, melodies so sweet they inspired William Cullen Bryant to commemorate them in poetry. Bobolinks make long journeys to return to Muskingum County. Most winter in Argentina.

Wintering raptors exploit Tri-Valley and other reclamation grasslands. Large numbers of Northern harriers, rough-legged and redtailed hawks, and short-eared owls converge to feast on abundant meadow voles—mobile furry sausages to the birds. Another reclamation grassland, the Wilds, has hosted golden eagle and prairie falcon—very rare wintertime visitors. Unnatural as they may be, Tri-Valley and other former strip mines still play host to important elements of Ohio’s bird life.