Central Lowland—

Till Plains

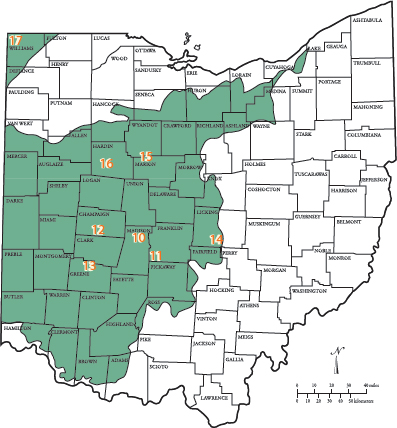

Bigelow/Smith Cemeteries State Nature Preserves (10) • Big and Little Darby Creeks (11) • Cedar Bog State Memorial (12) • Clifton Gorge State Nature Preserve (13) • Cranberry Island State Nature Preserve (14) • Killdeer Plains/Big Island Wildlife Areas (15) • Lawrence Woods State Nature Preserve (16) • Mud Lake Bog State Nature Preserve (17)

Bigelow/Smith Cemeteries State Nature Preserves

ACREAGE: 1½ (Bigelow ½; Smith 1)

OWNERSHIP: Pike and Darby townships (Bigelow and Smith, respectively) of Madison County. Managed by the Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves.

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.ohiodnr.com/dnap/location/bigelow_prairie.html

The first pioneers penetrating west-central Ohio ran into a daunting wall of vegetation—the unbroken expanse of tallgrass prairie of the Darby Plains. Sprawling over some 385 square miles, the prairie was dominated by Indian grass and big bluestem. These grasses grew so tall that a man on horseback could scarcely see over them.

Fire and prairie go together, and the Darby Plains regularly went ablaze. These conflagrations must have been awe inspiring but horrific spectacles to settlers. Dr. Jeremiah Converse, an early pioneer, wrote: “The blaze of the burning grass seemed to reach the very clouds … [flames] would leap forty or fifty feet in advance of the base of the fire. Then add to all this a line of the devouring element three miles in length, mounting upward and leaping madly forward with lapping tongue, as if it were trying to devour the very earth, and you have a faint idea of some of the scenes that were witnessed by the early settlers of this country” (Jeremiah Converse, History of Darby Township, Ohio, 1883).

As fearsome as fire can be, it is essential to prairie ecosystems. Prairie plants co-evolved with fire and are adapted to the specialized conditions that fire causes. Burning doesn’t affect deep-rooted prairie forbs and grasses but kills off shallowly rooted non-native grasses and invading woody plants.

Today, nearly nothing remains of the original Darby Plains prairie. This is true of Ohio’s prairies in general; over 99 percent have given way to the plow or development. That’s why these postage-stampsized graveyards are so special. As they were founded before the area was settled and tamed, Bigelow and Smith cemeteries harbor some of the only unplowed prairie sod in Ohio. Pioneers probably augmented the cemeteries with showy flowers as grave decorations, brought from surrounding prairie. Bigelow and Smith are the prairie equivalent to virgin forest, and the flora of the cemeteries offers a tiny glimpse into the spectacular, primeval prairie that our first settlers encountered.

One of the most amazing stories of the insect world is the annual peregrination of Monarchs to wintering grounds in lofty Mexican fir forests. From Ohio and points north, Monarchs wing their way south. Prairie remnants often host large numbers, as the butterflies gather to feed on blooms of various wildflowers.

Few plants are as characteristic of Ohio’s former prairie regions as royal catchfly. It was probably abundant in the presettlement prairie landscape. Today it is considered threatened and found in few locales. The odd name “catchfly” refers to the sticky calyx—the cup subtending the flower.

In the wild, showy purple coneflowers are nearly always associated with prairie remnants. Lush stands cloak Smith Cemetery in a blanket of midsummer purple.

Midsummer flowers bloom in profusion in small but spectacular Bigelow Cemetery. Sprays of scarlet royal catchfly and gray-headed coneflower brighten the faded headstones of prairie pioneers.

Big and Little Darby Creeks

Circle denotes location of Battelle Darby Creek Metro Park, one of the best sites to access the streams.

ACREAGE: Combined properties of Franklin County Metroparks, TNC, and ODNR total over 7,000 acres

OWNERSHIP: Miscellaneous

ACCESS: Best access via Columbus and Franklin County Metroparks. Metroparks open to the public during posted hours.

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.metroparks.net/

http://www.ohiodnr.com/dnap/sr/bdarby.htm

http://www.nature.org/wherewework/northamerica/states/ohio/bigdarby/

Flowing eighty-eight miles south from headwaters in the rolling hills of Logan County, the Darby confluences with the mighty Scioto River at Circleville. In spite of close proximity to the major metropolis of Columbus, this stream remains one of the most pristine in the country.

The Nature Conservancy declared the Darby watershed one of the “Last Great Places” in North America. Rightly so; this national treasure harbors an incredible array of aquatic life. Of 166 species of fish documented in Ohio, 103 are known from the Darby and its tributaries, including one that is likely extinct and was Ohio’s only endemic fish. On November 4, 1943, famed ichthyologist Milton B. Trautman was seining a fast-flowing riffle in Pickaway County when he netted a small, unknown catfish. It turned out to be new to science and was named the Scioto madtom. Collected on eight separate occasions afterward, it was last caught on November 17, 1957. It hasn’t been seen since.

Yet life aplenty remains in Darby waters, including a spectacular group of fishes—the warblers of the underwater world. Darters, tiny members of the perch family, live primarily in turbulent waters of riffles and chutes, foraging among gravelly substrates. Males morph into gaudy hues in late winter, rivaling anything found in domestic aquaria.

Hardest hit of all aquatic animals in Ohio are freshwater mussels, or unionids. Because of their specific foraging tactics, burrowing into stream bottoms and filtering out small organisms, mussels are vulnerable to smothering by sediment runoff. Fourteen of the eighty species once known to occur are extirpated from Ohio. The Darby, because of its excellent water quality, still harbors at least thirty-eight mussel species, including eight listed as endangered. Two of them, Northern riffleshell and clubshell, are federally endangered—the rarest of the rare.

One of twenty-four species of darters recorded in Ohio, greenside darters are common in the Darby and throughout much of Ohio. Males in breeding colors are striking. Unlike most fish, darters lack air bladders. This adaptation allows them to easily anchor on the stream bottom in the fast-flowing torrents that they favor.

The best populations of endangered spotted darters occur in the Darby, which is a stronghold for other rare fish and aquatic organisms.

Beautiful American rubyspots are common along the edges of Ohio streams, particularly around beds of water-willow.

Of the forty-seven species of sandpipers and plovers reported in Ohio, six remain to nest, and only three are common breeders. The spotted sandpiper nests along many Ohio waterways. A characteristic behavior is their habit of bobbing their tail.

Conserving streams and associated riparian corridors may have greater largescale impacts that any other preservation efforts. Protecting the Darby sends purer water into the Scioto River and then to the Ohio River. That great stream, which drains much of the Midwest, flows into the mighty Mississippi, then into the Gulf of Mexico. There is now a dead, deoxygenated zone the size of New Jersey in the gulf at the Mississippi’s mouth. This aquatic desert is caused mainly by farmland fertilizers and sewage running into the vast labyrinth of streams that form the Mississippi drainage.

Although seemingly dull, freshwater mussels have many interesting names. Pictured above are at least ten species. They include pink heelsplitter, lilliput, rabbitsfoot, and clubshell. Mussels have a reproductive cycle that defies belief. Some species lure suitable host fish near with an enlarged mantle—fleshy appendages that look like tasty food. When the fish draws near, the mussel blasts it with a spray of glochidia, or larval clams. The glochidia mature within the gills of the host fish and, once of a suitable size, drop off into the stream bottom. There, they may live for many decades.

Big Darby Creek and its major tributary, Little Darby, were designated a State Scenic River in 1984. A further recognition of wildness was awarded in 1994, when it received National Scenic River status by the federal government. As Ohio’s capital city, Columbus, sprawls outward, protecting the Darby will become one of our greatest environmental challenges. Hopefully we are up to the task.

Cedar Bog State Memorial

ACREAGE: 427

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Historical Society

ACCESS: Located at 980 Woodburn Road, one mile west of U.S. Route 68 and about two miles south of Urbana. Open during posted hours. Donations are very welcome at entrance kiosk.

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.cedarbog.org/index.htm

Stepping into Cedar Bog is akin to taking a leap back into the Pleistocene age. Many plants and animals here are glacial relicts, holdovers from long ago. A visitor will instantly notice something unique at this site. No other Ohio wetland is cloaked with dense growths of white cedar. This northern conifer is the defining feature of Cedar Bog, but only one of its many rare plants.

While the name is charismatic, Cedar “Bog” is actually a fen. “Bog” is an oft-employed catchall phrase for various wetlands. True bogs are glacial kettle lakes that fill with water and, over time, distinct vegetation. Fens flush. There is a constant energetic flow of water derived from subterranean aquifers. By the time cold artesian water bursts to the surface, it is supercharged with calcium precipitates derived from long passages through limestone beds. Fens are essentially big sheets of water upon which rests a blanket of highly specialized plants. The combination of high pH, cold root-level temperatures, and saturated soils creates growing conditions too tough for most plants.

Fens are built on sedges. Most plant biomass in Cedar Bog’s meadows is sedges, and as they die and decompose, gramineus peat is formed. Green cotton-grass (actually a sedge) is an Ohio rarity, as most cotton-grasses are true northerners. Only two species occur in Ohio, and both are scarce.

Creamy blossoms of the rare fen Indian-plantain ornament Cedar Bog meadows in June. Cedar Bog is filled with rare plants that are extremely habitat specific and often typical of boreal habitats found far to the north.

Endangered in Ohio, seepage dancers are known from only four other sites. Cedar Bog hosts the largest population of this tiny damselfly.

Rare plants abound here, foot for foot, more than any other Ohio habitat. At least thirty-five state-listed rarities occur, including some of the state’s most endangered species. One of the most spectacular is North America’s largest orchid, the showy lady’s-slipper. Pink and white blooms are the size of a small fist, and an opening in the pouch-shaped flowers accommodates large bumblebees, their principal pollinator. Other noteworthy plants include bog aster, prairie valerian, shrubby cinquefoil, and wand-lily.

A few species of carnivorous plants adorn Cedar Bog’s meadows. These miniature wonders of evolution have amazing strategies of coping with nutrient-deficient fen soils. The endangered horned bladderwort grows in the most alkaline barrens of marl flats, pushing forth beautiful yellow violetlike flowers. Their slender roots are beset with tiny bladders that capture miniscule animals. Bladders are armed with guard miniscule hairs surrounding a trap door of sorts, and prey is lured by specialized cells that secrete sugary chemicals. If a victim trips a few guard hairs, the trap opens inward so forcefully that the animal is instantly sucked inside. The door slams tight and internal secretions break down the bug, making its nitrogen and proteins available to the plant.

Rare animals persist at Cedar Bog, and two of the most interesting are the Eastern Massasauga rattlesnake and the spotted turtle. Both of these species have become scarce in Ohio as their wet prairie habitat has been largely destroyed. The turtle is our smallest species; a big one is five inches long. Shiny black and polka-dotted with yellow, spotted turtles are secretive and lurk in wet sedge meadows. Furtive in the extreme, Eastern Massasaugas are hard to find and sometimes live in crayfish burrows. They average about two feet in length and are often docile, but like any poisonous snake they can bite quickly. A colloquial name is black snapper (there are also many other colloquial names).

The 427 acres of Cedar Bog is a shard of the former seven-thousand-acre fen that once covered this region. Protecting what’s left is not without challenges. In the 1960s plans were forged that would have routed U.S. Route 68 hard on the east border of Cedar Bog. That intrusion would have been detrimental to the fen’s delicate ecology, and environmentalists successfully derailed the scheme. Today’s biggest challenge may be protection of groundwater that feeds the wetland. As development expands locally, degradation and disruption of hydrology become more likely and safeguarding wide-ranging water sources won’t be easy.

Few Cedar Bog visitors will be fortunate enough to glimpse the Eastern Massasauga. It is rare anywhere in Ohio. Most of its original wet prairie habitat has been converted to cropland.

Clifton Gorge State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 269

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Open during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.ohiodnr.com/dnap/location/clifton.html

http://www.ohiodnr.com/parks/parks/jhnbryan.htm

http://www.ohiobirds.org/birdingsites/showsite.php?Site_ID=5

The waters of the Little Miami River sluice through the rocky confines of Clifton Gorge. Steep walls of sheer limestone contain the stream, which jigs around gigantic slump blocks calved from the cliffs long ago. Ferns and other interesting flora grow thickly on the bedrock, and rare white cedars shoot precariously from rock-face crevasses.

You will often hear Clifton Gorge before you see it. The swift, rushing waters of the Little Miami River create a low roar that drifts up to the rim trails, providing an aural greeting for hikers.

This is an outstanding example of interglacial and postglacial stream cutting. Clifton Gorge’s birth dates to the Silurian age, over 400 million years ago. Then, a large sea covered what is now the Buckeye State. As this sea gradually receded, dolomite limestone—the substrate of Clifton Gorge—was formed by crystallization of various minerals. Much later, as modern patterns of drainage evolved, water exploited weaknesses in the rock and began carving the vast fissure today’s visitor sees.

Sheer rock walls line either side of the river, creating an impressive canyon unmatched elsewhere in western Ohio. Because of the depth of the gorge and the streams of subterranean fifty-six-degree air jetting from crevasses, the depths of the valley stay cool and shaded. This specialized microclimate allows northern plants to abound—far south of most of their brethren.

Boldest of the northern vegetation are white cedars, rooted precariously on the limestone escarpments and slump blocks. Plenty of botanical rarities can be found, most of which rarely occur this far south. A practiced eye might spot the crimson fruit of red baneberry, snowy blossoms of rock serviceberry, or the showy false melic grass. In all, over a dozen species of state-listed rare plants have been found.

The vertical cliffs and underlying talus slopes are a fern lover’s paradise. A few dozen species can be found, including cliff-face oddities such as smooth cliff-brake and mountain spleenwort. Streamside boulders are covered with colonies of walking fern, an interesting plant that arcs its leaf tips outward until they touch rock, whence they grow roots and shoot out a new leaf. Over time, they walk their way into new terrain and enlarge the colonies.

A diminutive rarity, the threatened wallrue is found in but a few Ohio sites. It is one of about twenty of Ohio’s eighty-five species of ferns that is an obligate saxicole—it only occurs on cliff faces.

Ohio plays an important role in the history of snow trillium. It was first discovered by pioneer botanist John Riddell in 1834 along limestone cliffs bordering the Scioto River in Franklin County. It also occurs in Clinton Gorge.

Centerpiece of the gorge is the Little Miami River, among our most pristine streams. The first river to be dedicated as scenic in Ohio (1969), it has also been federally designated as a scenic river, the first waterway to receive that status. Nearly ninety species of fishes and three dozen freshwater mussel species live in its waters—exceptional diversity and proof of the Little Miami’s outstanding aquatic habitats.

Louisiana waterthrushes are a true harbinger of spring. One of about sixty species of neotropical birds that nest in Ohio, the waterthrush is one of the first warblers of this group to return. Their loud rollicking song fills Clifton Gorge beginning in late March.

Cranberry Island State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 12

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: By permit only

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/location/cranberry.html

A need for improved commerce to service Ohio’s burgeoning postsettlement population accidentally created Cranberry Island. The 1830s ushered in the canal era; waterways accommodating horse-drawn barges were hailed as the answer to moving goods around the state.

Around 1834, construction of Buckeye Lake began. Its purpose was as a feeder lake for the Ohio-Erie Canal, allowing the channel to cross the divide between Ohio River and Lake Erie watersheds. The valley where the lake now sets was the site of an extensive bog, and as the newly created waters of Buckeye Lake slowly rose after damming, the youngest, most buoyant part of the bog began to rise.

As the bog ascended like a botanical phoenix, it remained rooted to the substrate; thus, Cranberry Island doesn’t really float. When it first surfaced, the island was about sixty-five acres; today it is perhaps twelve. A constant chemical clash between alkaline lake waters and acidic bog substrates melts away the island. A large tree occasionally topples along the edges, taking big chunks of the bog along. The island’s lifespan isn’t long, so see it while you can.

Cranberry Island is built on Sphagnum moss—peat—and these bryophytes exude acidity as a byproduct of their growth. Thus, the substrate is low in pH, holds water like a sponge, and creates refrigeratorlike root zone temperatures. Life in the bog is tough, and only specialized plants can thrive. One common plant every visitor should learn is poison sumac, which causes a blistering dermatitis.

Following a short boat ride from the mainland, visitors can easily traverse the bog via a boardwalk. The place lives up to its name—large cranberry blankets the meadows, so much so that locals once made cranberry-harvesting trips to the island. Pitcher-plants are everywhere and seem right at home here. However, they are thought to be the spawn of intentional introductions in the early 1900s.

To attract insect prey, pitcher-plants secrete aromatic compounds that lure victims into their pitcherlike leaves. Pitcher-plant juice is filled with proteins and nitrogen that allow the plant to grow in the harsh substrate of a peat bog. An American toad hides among these plants.

Many orchids, grass-pinks included, lack nectar. To compensate, grass-pinks rely on botanical subterfuge to attract insect pollinators.

The rose pogonia is one of forty-six species of native Ohio orchids. Addicted to acid soils, this striking species begins to flower in June.

Mid- to late June may be the best time to visit. That’s when bright pink blooms of two rare orchids, rose pogonia and grass-pink, enliven the meadows. The latter lures bees with an appealing brush of hairs on the upper lip. Seeking nectar, the insect alights and is promptly catapulted downward onto the column and is dusted with pollen. The bee, duped, gets nothing in return.

When naturally formed, bogs usually surround lakes, eventually filling them in with vegetation. Here, the opposite has occurred—possibly the only such site anywhere. While “unique” is an often misapplied and overused descriptor, truly it is accurate in regard to Cranberry Island.

Killdeer Plains/ Big Island Wildlife Areas

ACREAGE: 13,659

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Wildlife

ACCESS: Open to the public except for signed restricted zones

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

Short-eared owls were no doubt a common breeder in Ohio’s original prairies. Killdeer and Big Island can be productive locales for these grassland owls.

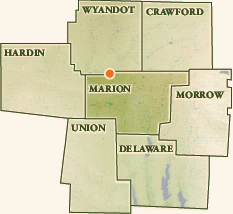

One of Ohio’s largest prairie expanses was the Sandusky Plains, which covered areas of Crawford, Hardin, Marion, and Wyandot counties. Until settlement, this mosaic of wetlands and oak savannas covered 192,000 acres. By far the largest protected piece of the Sandusky Plains is within these two wildlife areas, although they conserve but 7 percent of the original landscape.

Botanical remnants of our prairie past are especially evident at Killdeer Plains. Wet swales and roadside ditches support stands of prairie cord grass, wheat sedge, Riddell’s goldenrod, and prairie-dock. One of about one hundred plants originally discovered in Ohio, the goldenrod was first found in the 1830s by pioneer botanist John Riddell and named in his honor.

A great rarity is rope dodder. An odd morning-glory relative, it lacks chlorophyll and forms thick braidlike strands resembling orange pipe cleaners. Deriving nutrients by parasitizing host plants, it usually attacks Canada goldenrod or sawtooth sunflower. Heat from prairie fires is apparently necessary to crack the dodder’s thick seed coats and allow germination.

Grassy meadows at Killdeer provide refugia for three of Ohio’s rarest snakes. Small and ribbonlike, the plains garter snake is only known from Killdeer Plains. This relict colony is the easternmost known population. Eastern Massasauga rattlesnakes also inhabit wet fields and remain fairly common—Killdeer is one of their best Ohio strongholds. Stunning lime-colored smooth green snakes, which seldom reach two feet in length and are quite docile, also share the grasslands.

Big Island is mostly wetlands, which host myriad waterfowl, nesting bald eagles, migrant shorebirds, and rare breeding marsh birds. Three wetland cells at the south side of the area total nearly four hundred acres. Ducks and geese pack these marshes in spring and fall, and rare Ohio nesters such as American and least bitterns, king rail, redhead, and Northern pintail sometimes breed. Lush oases in seas of cropland, Big Island and Killdeer have lured many rarities, to the excitement of birders. Notables include long-billed curlew, Northern wheatear, white ibis, and black-necked stilt. The winter season brings roosts of long-eared and short-eared owls to Killdeer Plains. Raptors such as Northern harrier and rough-legged hawk become common.

Although most prairie sod in the Sandusky Plains has been tilled and planted to beans, corn, and wheat, birds that evolved migrations that correlate with prairie ecosystems still sweep through on great passages. Muddy fields of black prairie humus grow verdant crops but still lie bare in early spring. In April, large flocks of American golden-plover pass through; sometimes over a thousand whirl about fields delivering melodious haunting whistles. Returning from Argentinean pampas, they are headed to Arctic breeding sites, and the Sandusky Plains provide critical resting stops.

Killdeer and Big Island are part of the formerly vast Sandusky Plains, which historically blanketed thousands of acres. Virtually the entire original prairie is now farmland. Prairie plants such as prairie-dock still persist at Killdeer.

The loss of more than 90 percent of Ohio’s original wetlands has greatly reduced populations of water birds. The least bittern is now listed as threatened in Ohio. Small numbers of this heron species breed at Big Island and Killdeer.

Few animals better represent successful conservation in North America than the wood duck. Because of rampant overhunting and habitat loss in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, populations plummeted to the point where some ornithologists were predicting possible extinction by 1930. Increased protection of wetlands, regulation of hunting, and erection of nest boxes turned the tables, and today wood ducks are once again common.

Recent wetland restorations at Big Island have demonstrated the reclamation potential of former prairie. In the late 1990s the hydrology of hundreds of acres of former wetlands was revived by busting drainage tiles and constructing berms to trap water. Within two years, blue-winged teal, American coot, pied-billed grebes, and other water birds were nesting. In 2000, a pair of Wilson’s phalarope, a very rare prairie breeder, nested, then returned and bred again in 2002. This project showed that with a bit of creativity, prairies and the animals that use them can bounce back.

Lawrence Woods State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 1,035

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/location/lawrence_woods/tabid/905/

Default.aspx

Rescued in the nick of time, many large trees in Lawrence Woods were already marked with paint to indicate their imminent harvest when the site was acquired in 1997. Because the Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves successfully intervened, Ohioans can enjoy the largest protected old-growth woodland in western Ohio.

Prior to European settlement, woodlands like this were commonplace. Excepting some prairie regions, much of the western Ohio till plains were blanketed with forest, ranging from beech-maple and oak-hickory associations on higher grounds to elm-ash-dominated swamps on poorly drained sites.

A trip around the Lawrence Woods boardwalk offers a historical perspective into the vast forests that once covered this region. Elevated knolls, although only a few feet higher than the lowlands, support upland trees such as shagbark hickory and white oak. An interesting example of the latter occurs near the trail entrance. Twisted from some long-ago disturbance, this ancient white oak’s distorted trunk creates an almost perfect silhouette of a rhinoceros.

The lowest spots hold water and are choked with buttonbush, an aquatic shrub. Buttonbush swamps are pools of diversity within forest ecosystems, and the large one at Lawrence Woods is an outstanding example. Copious white blooms of buttonbush attract legions of pollinators: bees, moths, butterflies, and others. Tranquil black waters of buttonbush pools are usually fishless; thus, aquatic insect and amphibian larvae survival soars. Perhaps the most interesting amphibian breeding here is the tiger salamander. A behemoth, an adult may reach a foot in length.

A loud, ringing Teacher, Teacher, Teacher announces the ovenbird. This ground-feeding warbler walks about the forest floor gleaning through leaf litter. The nest is placed on the ground and resembles an old-fashioned Dutch oven.

Spring-beauties carpet Ohio woodlands in April with boldly striped pink flowers. It and scores of other wildflowers provide a visual vernal feast in Lawrence Woods.

A summertime visit to Lawrence Woods’ buttonbush swamp bears out the importance of this habitat for dragonflies. Myriad Eastern pondhawks, common green darners, black saddlebags, and blue dashers hunt, mate, and fight over the sheltered waters.

The soupy outflow of the buttonbush swamp forms a swampy wetland with a plant community unique in Ohio. A mucky quagmire sports over one thousand plants of the endangered heart-leaved plantain. Their large, cabbagelike leaves contrast with the strap-shaped fleshy leaves of tubercled rein orchid, which grows intermixed. Nowhere else in Ohio do these two rarities occur together.

Plenty of birds breed here, and woodpeckers are especially obvious. All six of Ohio’s common nesting species are found. Large oval-shaped excavations from crow-sized pileated woodpeckers are conspicuous, and visitors are likely to hear the maniacal laughing calls of this giant, if not actually see the birds. Old pileated nest holes are particularly valuable to the forest ecosystem. Multitudes of other animals utilize these cavities, including Eastern screech-owl, gray and Southern flying squirrels, Virginia opossums, black rat snakes, and raccoons.

April and May are spectacular. The woodland teems with dozens of species of wildflowers in nearly every hue of the rainbow. Violets are especially eye-catching, and at least a third of the twenty-seven native species can be found. The forest floor is thick with other species, including various trillium and waterleaf, cut-leaved toothwort, wild geranium, wild blue phlox, and bloodroot.

Wood frogs congregate in shallow breeding pools. Their ducklike quacking call is distinctive. This one is with early blooming hepatica.

With the first warm rains of spring, spotted salamanders migrate to vernal breeding pools, where females lay jellylike egg masses.

Mud Lake Bog State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 74

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Access by permit only

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.ohiodnr.com/dnap/permitonly/tabid/863/Default.aspx

Mud Lake is the best remaining example of a glacial lake in northwestern Ohio. There aren’t many competitors. Williams County was once dotted with numerous kettle hole bogs, but most have succumbed to the inexorable forces of ecological succession. Only from the air in leafless winter can one get a true sense of the former abundance of bogs, as circular depressions grown over with vegetation dapple the landscape.

Almost perfectly round, Mud Lake is ringed with rare flora. The western side is dominated by tamarack underlain with luxuriant beds of Sphagnum moss. The eastern side is more fenlike; alkaline seeps foster vegetation characteristic of high pH soils. Everywhere things are wet, and visitors on foot must tread carefully or risk being sucked into the mire.

Although the lake and its associated habitats cover only sixteen acres, rare animals and plants abound, offering one of Ohio’s densest concentrations of extraordinary species. Thirteen species of threatened or endangered plants grow here, and nine species of equally rare animals live in or around the lake.

The muck-bottomed lake’s cold water harbors noteworthy aquatic plant communities. Rare floating and flat-stemmed pondweeds grow with threatened American water-milfoil, forming dense underwater tangles. Iowa darters and lake chubsuckers, fish species dependent upon excellent water quality and intact aquatic plant associations, live in the submerged foliage. Showy white blooms of fragrant water-lily hang on the water’s surface, their circular floating leaves providing landing pads for one of Ohio’s rarest damselflies, the lilypad forktail. This tiny insect is only known from Mud Lake and wasn’t discovered here until 1992. On the other end of the dragonfly size scale are Canada and mottled darners, both endangered. These large mosaic darners are brightly colored with tints of blue, green, and yellow and occur no farther south.

Nearby swamp forests harbor the federally threatened copperbelly water snake. A bruiser, this fiery-tempered reptile can reach six feet in length. Like most snakes they are furtive, but this species is particularly difficult to locate as it occurs in wet, hard to access habitats and is quite secretive. Shiny coal-black above, and bright orange-red below, copperbellies are extraordinarily showy reptiles. Williams County habitats support some of the few remaining relict populations of this snake.

A botanist can’t take two steps along the shore without finding a rare plant. Shrub thickets are populated with swamp birch and slender willow, threatened and endangered, respectively. Boggy mats are rich with unusual flora, including one of the few Ohio stands of small purple foxglove. This diminutive figwort has stunning magenta blossoms prominently streaked with violet nectar guides to lure insect pollinators. Rarer yet is swaying-rush. This sedge of northern glacial lakes grows in deep lake waters, only its flowering tips protruding. Rooted in quicksandlike mire, it is physically impossible to reach on foot. Swaying-rush is one of nine state-listed rare sedges growing at Mud Lake.

Mud Lake Bog contains an outstanding odonate fauna. Beautiful dragonflies like this painted skimmer can be seen as well as rarer species like Canada darner.

Most of the 108 glacial lakes in Ohio have been degraded and no longer support high fish diversity. Lake chubsuckers require abundant aquatic plants, clear cold water, and clean lake bottoms.

Breeding primarily in peatlands, alder flycatchers are local in Ohio. Alder and the more common willow flycatcher can only be identified by song.

Protection of the waters that flow into glacial lakes is a key to their conservation. Many aquatic organisms that inhabit pristine habitats such as Mud Lake are sensitive to water-quality degradation. Fortunately, the Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves has protected much of Mud Lake’s drainage, ensuring that future generations can study the flora and fauna of this fascinating ecosystem.

An endangered species, purple fringed orchids are known from perhaps six Ohio sites, with few individuals present in each population. Collectively, there may be fewer than one hundred plants in the state.