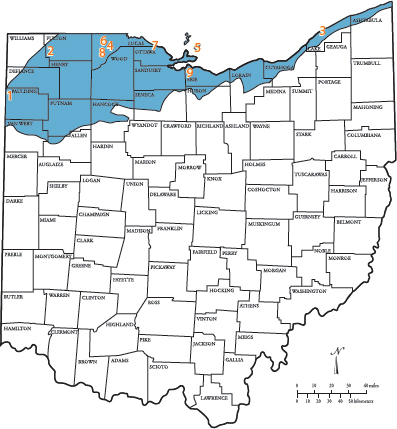

Huron-Erie Lake Plains

Forrest Woods Nature Preserve (1) • Goll Woods State Nature Preserve (2) • Headlands Dunes State Nature Preserve (3) • Irwin Prairie State Nature Preserve (6) • Kelleys Island (5) • Kitty Todd Preserve (4) • Magee Marsh Wildlife Area/ Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge (7) • Oak Openings Preserve (8) • Resthaven Wildlife Area (9)

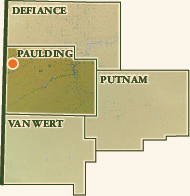

Forrest Woods Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 257

OWNERSHIP: Black Swamp Conservancy

ACCESS: By permit only through Black Swamp Conservancy

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.blackswamp.org/

Rivers are America’s arteries, distributing plants and animals throughout the landscape. Marie DeLarme Creek, a tributary of the Maumee River, flows through the center of Forrest Woods. Near Fort Wayne, Indiana, a low-lying glacial outwash terrace has provided a natural conduit from Mississippi River drainages into the Great Lakes. For eons, southern species have migrated through this gap and infiltrated western Ohio as a result. Some of them occur in Forrest Woods, perhaps the best remaining riparian woodland on the Till Plains.

Forrest Woods lies on the southern periphery of what was once Ohio’s greatest expanse of wetlands—the Great Black Swamp. The area stretched from present-day Lake Erie west to Indiana and south to the Maumee River, and early settlers avoided it like the plague. It wasn’t until the 1820s when the first roads were hacked through the swamp, but by the late 1800s nearly the entire quagmire had been drained and transformed to croplands.

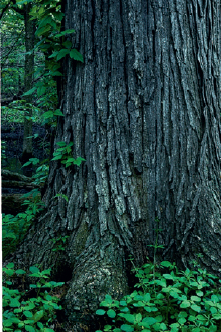

Visitors to Forrest Woods, especially during spring floods, will experience the daunting landscape faced by Great Black Swamp trailblazers. Towering wetland trees like green ash, swamp white oak, and American basswood shade the swampy oxbows. Part of the package are mosquitoes, sometimes in dense clouds. Braving the insects is worth it—this is one of Ohio’s only remaining old-growth tracts of river bottom woods in western Ohio.

Heavy spring rains inundate the bottomland swamp forests. Standing water pools for weeks in oxbows and depressions, creating habitat for specialized plants such as raven-foot sedge and leafy blue flag, both rare in Ohio. Botanists found an odd parasitic morning-glory relative here, cuspidate dodder, a first for Ohio and far removed from its western range.

Forrest Woods is a vital refuge for breeding birds, as most of the great swamp forests that covered western Ohio no longer exist. Birds like yellow-throated warbler, Louisiana waterthrush, and cerulean warbler nest here but are rare elsewhere in the region.

Protection of Forrest Woods has ramifications far beyond conserving this woodland and Marie DeLarme Creek. As the stream flows into the Maumee River, its water quality directly influences that of the Maumee, one of Ohio’s officially designated scenic rivers. The Maumee is also Lake Erie’s largest tributary, so its waters have a direct impact on the health of our greatest lake.

The vociferous red-eyed vireo is the most numerous neotropical migrant breeding in the deciduous forests of eastern North America. One male was documented singing over twenty-two thousand songs in one day. Territories can be as little as an acre or two, so even small woodlands can host several pairs.

Large and handsome, the Blanding’s turtle can easily be recognized by its high-domed carapace and bright yellow throat. Never common, this species has a rather limited range. The Forrest Woods population is the southernmost known in the state.

One of twenty-four species of salamanders in Ohio, the secretive four-toed salamander has been recorded from widely scattered locales throughout the state. Four-toeds breed in forested wetlands. Their eggs are laid under a cloak of moss, and adults remain to guard them until they hatch.

Goll Woods State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 321

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/location/goll_woods.html

http://www.ohiobirds.org/birdingsites/showsite.php?Site_ID=56

Among the finest stands of old-growth timber remaining in Ohio, mammoth bur and red oaks, black ash, and tulip tree form a woodland cathedral at Goll Woods. The eighty-acre big woods are about all that’s left of the Great Black Swamp, which blanketed much of the northwestern corner of the state well into the 1800s.

About 150 years ago, the region of Goll Woods was a wild place full of giant trees. The landscape was waterlogged and seemingly impenetrable. Animals long since vanished from Ohio were common: gray wolves, lynx, cougar, and black bear. An intrepid pioneer, Peter Goll, was one of the first to settle in this area, buying the land now occupied by Goll Woods in 1837 for $1.25 per acre.

Fortunately, the Goll family preserved a chunk of old-growth woods as nearly all the rest in the region fell to the axe and was converted to fields of beans and corn. In 1966 the Ohio Department of Natural Resources acquired Goll Woods, and today it is a state nature preserve.

Some of the trees stand over 120 feet tall and exceed twenty feet in circumference. Such a goliath can remove up to fifteen pounds of airborne pollutants annually and put thirty pounds of oxygen back into the atmosphere. Giant oaks also produce bumper crops of acorns. The nuts provide forage for gray squirrels, wild turkey, white-tailed deer, and others.

Spring wildflowers flourish in April and May, before leafy canopies shade the forest floor. Carpets of large-flowered trillium, cut-leaved toothwort, and bloodroot blanket the forest floor. Summer brings dense shade and fewer wildflowers, but one plant is especially noteworthy. One of few Ohio populations of the threatened three-birds orchid grows around the bases of massive American beech trees. This tiny orchid is largely subterranean and may only send stems and flowers above ground once every several years.

No Ohio forest fragment can truly be considered virgin. All have suffered some intrusion by the hand of man, and this is true of Goll Woods. As World War II accelerated and America became increasingly engaged, demand for timber to build ships escalated. Some of the huge trees in Goll Woods were harvested and their wood processed to provide flooring and other battleship accoutrements. Luckily, most of the sylvan giants have been spared for visitors to enjoy.

An outstanding feature of Goll Woods is the abundance of bur oaks. Some magnificent old trees in this old-growth forest are four feet in diameter.

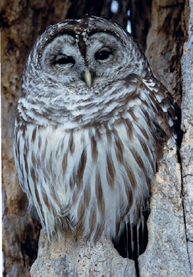

One of three species of common, widespread breeding owls in Ohio, barred owls are strictly woodland dwellers. They do best in mature, swampy forests or ravines, and are most often detected by their calls.

A delicate member of the buttercup family, hepaticas are often characteristic of rich woods, where they occur in association with many other native wildflowers.

Headlands Dunes State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 25

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/location/headlands.html

Everybody loves a beach. That’s been the downfall of most of Lake Erie’s natural shoreline habitats—they’re overrun with recreational users. At one time, over 170 miles of unsullied coastline stretched along Ohio’s north coast; today, Headlands Dunes harbors the best of the few remaining lakefront plant communities.

The low sand dunes of Headlands, carpeted with thick stands of grasses, stand in stark contrast to the state park beach immediately to the west. There, most evidence of plants is eradicated—victims of decades of unrestricted trampling by visitors.

Although abundant at Headlands, two of the dominant grasses are rare in Ohio, confined strictly to a few isolated, undisturbed beaches. American beach grass forms lush stands on the outermost dunes. The tough rhizomes of this grass provide vegetative reinforcement to loose sand, preventing erosion. Just alee in sheltered swales are blankets of coastal little bluestem, another lakefront rarity.

Like botanical museum pieces, rare Atlantic coastal plain disjuncts grow on the wave-washed forebeach. Migrants of long ago, when Lake Erie was connected to the Atlantic seaboard by a band of postglacial wetlands, a handful of species persist in the Great Lakes. One of the most interesting is seaside spurge. This diminutive annual grows pancake-flat in sands just above the waterline and quickly exploits new habitats in ever-changing conditions.

Headlands is legendary among birders. Over 310 of the 418 bird species thus far recorded in Ohio have been found here, including many rarities. Headlands’ location, coupled with good foraging and resting habitat, conspires to create a migrant trap perhaps unequaled elsewhere in the state. Large fallouts of songbirds occur routinely in spring and fall; it’s not unusual to tally over twenty-five species of warblers in a morning.

Headlands Dunes preserves one of the last and best beach dune communities in the state. Many coastal plain plant species survive here.

Inland sea rocket is one of a small suite of Lake Erie beach plants that are Atlantic Coastal Plain disjuncts. These beachdwellers likely migrated westward via an interconnected band of lakes and wetlands that stretched east-west along the face of the retreating Wisconsin glacier some twelve thousand years ago and gradually became isolated.

Waterbirds galore are attracted to Headlands’ beach, the sheltered harbor of the Grand River (Fairport Harbor), and offshore waters of Lake Erie. In November, hordes of migrant Bonaparte’s gulls gather by the thousands, and tens of thousands of red-breasted mergansers swarm in the lake. In swirling masses so thick they resemble fast-moving storm clouds, over 100,000 mergansers have been tallied passing by within a few hours. This is also the time of year to watch for migrant loons and tundra swans. Veteran birders enjoy looking for rarities like king eider, Northern gannet, black-headed and mew gulls, and jaegers.

The pink and purple flowers of this threatened species brighten the grassy dunes of Headlands. Inland beach pea has an amazing circumboreal distribution, occurring on beaches at northern latitudes around the globe. Its far-flung range is accounted for by the seeds, which can remain viable and buoyant in water for up to five years.

Rare away from the Atlantic coast, small numbers of purple sandpipers migrate through the Great Lakes in November and December. The stone jetty at Headlands beach has become the premier locale in Ohio for finding this rarity.

Irwin Prairie State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 187

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/location/irwin_prairie/tabid/

946/Default.aspx

Irwin Prairie is Ohio’s counterpart to the Everglades. The sedge that dominates the meadows is twig-rush. Its only eastern equivalent is saw-grass, which blankets the vast Florida wetlands.

The area is waterlogged year-round; an impervious clay layer underlies the wetlands, trapping water on the surface. Fortunately, a mile-long boardwalk allows easy access to the meadows, offering an opportunity to observe unusual flora and fauna. And there’s plenty of that—at least twenty-six species of rare plants have been found. Many are sedges and other obscure species that require a skilled botanist to identify. Others are obvious.

Sharp eyes might spot the saclike flowers of large yellow lady’s-slipper in May. Stroll to the observation tower in the wettest part of the meadows and watch for the three-parted white blooms of endangered grass-leaved arrowhead. In late fall, gorgeous blossoms of small fringed gentian can be seen along the walkway, their rich cobalt flowers looking as if they were spun from silk.

A captivating avian spectacle commences in March. Wilson’s snipe, an odd sandpiper with a long bill, begin their courting antics. Males circle skyward and, at the apex of their ascent, suddenly drop landward. Wind whistling through their uniquely fluted tail feathers creates a surreal winnowing sound unlike any other aural display in Ohio.

Interesting marsh birds dwell in the wettest portions of the prairie. American and least bitterns have nested, as has Virginia rail. The metallic trills of swamp sparrows are easily heard, and sometimes marsh wrens add their sewing machine–like chatter to the mix. Rare Ohio nesters such as Canada and mourning warbler have been found in June and may occasionally breed.

The dominant plant in the wet meadows at Irwin Prairie is a sedge–twig-rush. Its close relative and ecological counterpart is the sawgrass of the Florida Everglades.

Breeding early in the spring, Northern leopard frogs utilize vernal pools. Their young leave before the pools dry out.

Irwin Prairie produces amphibians by the score. Early spring symphonies of spring peepers and western chorus frogs can be deafening, drowning out lesser songsters. Frogs are vital to wetlands; each individual is a voracious predator, consuming large quantities of mosquito larvae and other insects.

Oak Openings wetlands like Irwin Prairie are difficult to protect. As development expands in the region, insidious threats arise that impact sensitive habitats. Basements and waterline excavations wick groundwater away, speeding desiccation of nearby moist habitats. Drying of wetlands gives an edge to invasive plants like glossy buckthorn, a scourge of Oak Openings ecosystems. Extensive areas of Irwin have been overtaken by this noxious shrub. Fortunately control measures implemented by the Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves have beaten it back, at least temporarily.

No place in Ohio resembles the Oak Openings, nor hosts the tremendous number of rare species found here. Lucas County, the Oak Openings epicenter, has more state-listed rare plants and animals than any other Ohio county. Conservation of these sensitive habitats is a challenge, especially as development pressures grow.

The small fringed gentian appears in late summer, growing in wet meadows and seeps. The beauty of this plant inspired poet William Cullen Bryant to pen a poem entitled “To the Fringed Gentian.”

Wilson’s snipe are at the extreme southern end of their breeding range in Ohio. Irwin Prairie is one of few reliable sites where the peculiar aerial courtship displays of male snipe can be observed.

Kelleys Island

ACREAGE: 2,800

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Department of Natural Resources (710 acres), Cleveland Museum of Natural History (120 acres), the remainder private

ACCESS: Park and museum lands open to public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/location/alvar/tabid/916/Default.aspx

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/location/NorthPond/tabid/952/Default.aspx

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/parks/lakeerie/tabid/753/Default.aspx

http://www.cmnh.org/site/Conservation_NaturalAreas_Map_KelleysIsland.aspx

The Lake Erie islands have been heavily developed, and most have lost much of their natural attributes. Kelleys Island, thanks to conservation efforts by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, has retained many of its ecologically significant features.

Devonian-age rock that forms Kelleys Island is part of the Columbus limestone formation. This rock formation is harder and more resistant to erosion than the surrounding strata, which have eroded away leaving elevated knobs, now surrounded by the waters of Lake Erie. These offshore islands are referred to as the Marblehead archipelago. Kelleys Island is the geological standout because of its famous grooves etched deeply in the rock, an excellent example of glacial scouring.

Much of Kelleys Island’s eighteen-mile shoreline is rimmed in low, rocky cliffs. On the exposed northern exposure of the island is a superb example of an alvar, one of Ohio’s rarest habitats. Alvars are wave-battered rocky shorelines that support specialized flora, and this one is protected as North Shore Alvar State Nature Preserve. Many beautiful, intriguing plants grow on the alvar. In May, golden blooms of balsam squaw-weed and deep purple Northern bog violets stand in stark contrast to their barren rocky habitat. Both plants are endangered in Ohio.

In warmer months, offshore waters sport plenty of Lake Erie water snakes. Like mini seaserpents, these rare reptiles often swim with just their heads protruding. Demonstrating an excellent example of geographic isolation, this subspecies of the widespread Northern water snake has become separated from the parent species and only occurs on Lake Erie islands. It is listed as federally threatened.

The giant swallowtail is commonly seen on Kelleys Island, where one of its primary host plants, wafer-ash, is frequent.

One of Ohio’s most famous and widely viewed geological features are the glacial grooves of Kellys Island. Some thirty thousand years ago, tongues of ice from the Wisconsin glacier moved south, cutting three-foot grooves in the Columbus limestone.

The Eastern fox snake has one of the most localized distributions of any North American snake, occurring only in Michigan, Ohio, and Ontario, Canada. In Ohio, they are only found on the Lake Erie islands and in some northwestern counties.

Harebells typically grow on wave-splashed limestone cliff faces above the waters of Lake Erie. Endangered in Ohio, harebells only occur on the Lake Erie islands, with the exception of one isolated Miami County population.

The finest remaining wetland on a Lake Erie island is North Pond State Nature Preserve. This mixed-emergent marsh supports native wetland vegetation like swamp rose-mallow, giant bur-reed, and the endangered wapato. Swampy woods buffer the wetland and attract scores of migrant birds. Warblers, vireos, tanagers, thrushes, and others settle here in migration to rest and refuel. Over 260 species have been recorded on Kelleys Island, including the federally endangered Kirtland’s warbler. Catch a good fallout in May or September migratory peaks, and the trees can be dripping with songbirds.

Rocky shorelines and open waters of Lake Erie also harbor significant congregations of water birds. Gulls and terns of several species are common, including great black-backed gulls. This massive scavenger weighs 3½ pounds and has a 5½-foot wingspan, making it the world’s largest gull. Adults are striking with charcoal-colored mantles contrasting with pure white underparts.

The smallest duck in Ohio is the thirteen-ounce bufflehead. These piebald divers are hardy, and migrant flocks collect in icy Lake Erie waters off Kelleys Island in November and December. Several thousand of the ducks sometimes gather—a significant percentage of their global population.

Late summer and fall bring migrating Monarch butterflies to the island. These globetrotters are powerful fliers and routinely cross Lake Erie. Compounds within the butterflies engage the earth’s magnetic field, pulling them on a steady southwestern course toward Mexican wintering grounds. Kelleys Island offers a resting spot after the lake passage, and occasionally masses of butterflies encrust the trees.

One of only six federally listed rare plants in Ohio, the state-endangered Lakeside daisy is only known from the Marblehead Peninsula of Ohio, and a few sites in Michigan and Ontario, Canada. While not indigenous to Kelleys Island, plants were transplanted here from Marble-head—three and one-half miles away—in the early 1990s to establish new colonies. The mass blooming of this very rare plant is one of Ohio’s greatest botanical spectacles.

Kitty Todd Preserve

ACREAGE: 500

OWNERSHIP: The Nature Conservancy

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.nature.org/wherewework/northamerica/states/ohio/

preserves/art162.html

The Oak Openings were named for the open, parklike savannas that were present at the time of European settlement. Scattered large black and scarlet oaks shadowed an understory of grasses and unusual herbaceous flora—a landscape so unfettered by trees and shrubs that settlers could easily pilot wagons through the region.

Fire was the instrument that maintained these habitats, and Indians were the main incendiary agents. For thousands of years native tribes lit infernos that raced through the Oak Openings, torching saplings and brush but sparing thick-barked fire-resistant big oaks. Many herbaceous prairie plants co-evolved with fire, as heat and flame are essential ingredients for their survival.

Fire performs several essential roles in the Oak Openings. Burning creates open, sunny conditions necessary for sun-loving plants. Periodic blazes scrub duff layers—dead mats of plants—from the soil, promoting easier growth of new plants. Following a burn, massive infusions of ash coat the soil, providing a burst of nutrients into the ground. Lastly, some prairie plants seem to require the tremendous heat of burns to crack dense seed coats and permit germination.

Man fears seemingly uncontrolled wildfires, and for roughly two hundred years postsettlement, fire was largely suppressed. After The Nature Conservancy acquired Kitty Todd, managers began to reintroduce fire. The results have been spectacular, and this preserve is among the finest examples of an Oak Openings savanna ecosystem.

In May, clumps of blue-flowered wild lupine dot sandy savanna soils. This plant nearly disappeared during the fire suppression era as its open haunts became overgrown with invading trees and shrubs. Tangential to lupine decline was the loss of the Karner blue butterfly. Now that the butterfly’s host plant has made a comeback, efforts to reintroduce the blue to Kitty Todd have met with some success. This is currently the only Ohio locale where enthusiasts have a shot at finding this endangered species.

A large snake of the sandy barrens is the blue racer. They can exceed six feet in length and are tinted in rich indigo hues. As the name implies, they are speedy, and adults can hit twelve miles per hour for short bursts. Hunting racers move about with heads elevated, cobra style, and look intimidating. They’re best left alone; if molested, racers won’t hesitate to bite. Racers are arboreal and may climb trees when pursued.

Damp swales concentrate rare wetland plants, many of which seldom or never occur outside the Oak Openings in Ohio. In early July, white spires of colic-root flowers pepper low-lying areas of the prairie. This rare lily produces an interesting aloelike rosette of broad leaves. Where spikes of colic-root blooms are seen, further botanical investigation is warranted. Other rarities often accompany it, such as twisted-yellow-eyed-grass, Atlantic blue-eyed-grass, cross-leaved milkwort, and lance-leaved violet.

In a good year, there probably aren’t more than a few dozen pairs of lark sparrows breeding in Ohio. Shifting eastward from the Great Plains during the warmer and drier Xerothermic period, the Oak Openings population is the easternmost known.

Wild lupine, with its racemes of blue flowers, contrasts with the orange flowers of plains puccoon. Both plants are rare in Ohio. Wild lupine is the host plant for the endangered Karner blue butterfly.

Forty-six native orchid species have been recorded in Ohio. Like the threatened yellow fringed orchid, most have become rare due to habitat loss.

Almost an Oak Openings exclusive, the spathulate-leaved sundew grows on moist sand. Sticky hairs on the leaves trap insects.

The highest, driest sand knolls may shock botanical neophytes. Some are carpeted with thorny growths of prickly-pear, Ohio’s only native cactus. They bear stunning yellow blossoms in June. Other rare xerophytes grow nearby, including Bicknell’s sedge, scaly blazing-star, and dotted horsemint. Among the rarest is the endangered prairie fern-leaved false foxglove. Despite its cumbersome moniker, it is one of our showiest wildflowers and is known from only a handful of Oak Openings locales.

Magee Marsh Wildlife Area/Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge

ACREAGE: 11,000 (Magee 2,000; Ottawa 9,000)

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Wildlife, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours. Some areas off-limits

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/Portals/9/Images/wildarea/magee.gif

http://www.ohiobirds.org/birdingsites/showsite.php?Site_ID=69

Ohio’s greatest natural resource and most dynamic geological feature is Lake Erie. Only sixteen thousand years old, this geological youngster has been in its present configuration for only five thousand years. Shoreline conditions change rapidly, and beaches and wetlands have shifted dramatically over the past century. Events called seiches, caused by strong winds, can pile up water sixteen feet higher than on the downwind side of the lake. Overnight, wetlands with two feet of water become mudflats, only to fill again later that day.

While natural phenomena has changed western Lake Erie’s vast marshes, so have people in the past 150 years. Much former marshland has been drained and converted to farmland. Most areas have been impacted by dike construction to manage water levels. Roads and railroad tracks have obstructed natural drainage. Nonetheless, the western Lake Erie marshes remain our biggest contiguous wetlands and one of the most significant biological hotspots in North America.

Magee Marsh is one of the most famous birding locales in the country. Tremendous fallouts of neotropical migrants fill trees and bushes in May, attracting thousands of observers from all over the country. On International Migratory Bird Day (the second Saturday in May), over five thousand birders often converge here. They come to visit a seven-acre woodlot bisected by the “bird trail.” This elevated boardwalk traverses wet woods of box-elder, cottonwood, and green ash, and migrant birds are often at one’s fingertips.

If suitable weather conditions create a “big day,” this coppice of trees may be packed with migrating songbirds. Mid-May brings peak numbers and diversity, and a skilled birder might tally over one hundred species in a morning. Staggering numbers of colorful jewels like scarlet tanager, Baltimore oriole, rose-breasted grosbeak, and indigo bunting are everywhere, with warblers generating the most excitement. All thirty-seven species that migrate through Ohio pass through this region, and most can be seen on a good day at Magee. Scores of magnolia, black-throated green, Nashville, bay-breasted, and blackpoll warblers feed in a frenzy along the trail. This is the best spot in Ohio to catch the federally endangered Kirtland’s warbler. More migrants have been detected at Magee and vicinity than any other locale.

Small numbers of red-necked phalaropes pass through Ohio en route between Arctic breeding sites and marine wintering grounds in southern oceans. The impoundments at Ottawa can be a good place to view shorebirds.

March and November are prime months to find migrant tundra swans at Magee Marsh and vicinity. During mild winters, large numbers remain in the region.

Upon their return from wintering grounds in the Caribbean and in Central America, large numbers of indigo buntings can bunch up at migratory hotspots like Magee Marsh. This is a common breeding species, found in all eighty-eight counties.

To reach the bird trail one must drive the causeway road that bisects one of Ohio’s finest marshes. Filled with diverse native flora, these wetlands support myriad migrant and breeding birds. All of the regularly occurring waterfowl can be found, as well as rarer birds such as king rail, American and least bitterns, black tern, and snowy egret. The overall feel is Floridian, with dozens of great egrets and great blue herons stalking prey in roadside ditches.

Just to the west of Magee is Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge, Ohio’s only federal refuge. Part of Ottawa includes rocky West Sister Island, an eighty-two-acre outcrop nine miles out in Lake Erie. Our only federally designated wilderness area, the island supports a rookery of several thousand water birds, mostly great blue herons, black-crowned night-herons, great egrets, and double-crested cormorants. Most herons seen foraging at Magee and Ottawa nest on West Sister Island.

The year 1979 marked the low point of breeding Ohio bald eagles, with only four nests. With the ban on DDT, eagle populations rebounded. In 2008, there were 184 nests known in Ohio.

The raspy cadences of scarlet tanagers are a common sound in Ohio woodlands. One can get great looks at this species as well as many other neotropical migrants at the Magee Marsh boardwalk.

Ottawa’s several thousand acres of marshes lure birds galore, and when low water levels coincide with shorebird migration, scores of waders congregate. Most plovers and sandpipers breed in the high arctic and spend the winter along the southern U.S. coast and as far south as Argentina. Resting habitat is vital in transit, and Lake Erie marshes are critical stopovers for these transglobal wanderers. August mudflats can support up to twenty-five species simultaneously, including rarities like marbled godwit, American avocet, and buffbreasted sandpiper.

Stubby little semipalmated sandpipers, which stop at Ottawa in large numbers, illustrate the global significance of this resource. These six-inch shorebirds weigh less than an ounce and breed in tundra 1,200 miles or more to the north of Ohio. They winter along South American coasts, and some of these diminutive sprites travel 8,500 miles one way, 17,000 miles round-trip. Vast mudflats that allow them to rest and refuel are essential. How we protect and manage Ohio lands links intimately to global biodiversity.

Oak Openings Preserve

ACREAGE: 3,668

OWNERSHIP: Metroparks of the Toledo Area

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.metroparkstoledo.com/metroparks/oakopenings/

No area in Ohio supports a greater density of rare flora and fauna than this 130-square-mile region. At present, over one hundred species of state-listed rare plants and at least twenty rare animals have been documented.

Sand defines the Oak Openings; the region is like an enormous sandbox. To what do we owe all this sand? Lake Erie, from a time long ago, when it was much larger. Prior to the last glaciation about twelve thousand years ago, our Great Lake sprawled into present-day Fulton, Henry, Lucas, and Wood counties. As glacial ice retreated northward, outlets were opened that partially drained Lake Warren—Erie’s much larger predecessor—stranding its beaches and dunes far from the water.

A striking example of an Oak Openings dune is near the junction of Girdham and Monclova roads. The open sandscape supports all manner of rare flora and fauna, from miniscule antenna-waving wasps to robust blunt-leaved milkweeds. Nature abhors a vacuum, though, and open sands are constantly under siege by pioneering plants. Most dunelike Oak Openings habitats have long been overgrown in a process known as ecological succession. Also, many of the wet prairies have been tiled and drained. The greatest botanical diversity occurred in the 1920s and prior, before development pressure claimed many of the wetlands.

Botanical pioneers of open sand are themselves rare. Starved panic grass and low sand sedge form dense tussocks, stabilizing shifting sands and providing other plants a foothold. Eventually, various herbs spring up within grass and sedge colonies, followed by shrubs such as sand cherry and ultimately seedling oak trees. The ecological finale is one of mature oaks, a forest entirely different floristically than the ancestral sandy dunes.

Oaks tinge woodlands in muted reds, oranges, and yellows in October. Progressive, interventive management by a variety of land-managing agencies has restored some of the Oak Openings savannas to their original condition.

Rare animals and rare plant communities go together, and some extraordinary beasts roam the Oak Openings. This is one of few Ohio locales where American badgers are regular. Big and ill-tempered, these burly brutes excel at burrowing. They probably migrated into Ohio four thousand years ago during the warmer Xerothermic period, hot on the heels of favored prey, thirteen-lined ground squirrels.

At the other end of the scale is the tiny Karner blue butterfly. Endangered and only found in the Oak Openings, this insect tells an ecological tale. Most butterflies are linked to specific plants, and Karner blues require wild lupine. Lupines need open sandy habitats that are maintained by fire. When fire is suppressed, as it was through much of the twentieth century, lupines disappear as shrubs and trees invade. Several management agencies have reintroduced fire management, and lupines and Karner blues once again brighten the landscape.

State-endangered fringed polygala is an Oak Openings rarity. Ironically, it is an abundant species of the north woods.

Always a very rare Ohio breeder, golden-winged warblers have essentially disappeared. Until the mid-1900s, the Oak Openings was our stronghold for them. A cause of decline is genetic introgression with a closely related species, the blue-winged warbler.

Not often thought of as home to cacti, Ohio does have one native species. Prickly-pear is a relict of a time when Ohio was much hotter and drier but persists on Oak Openings dunes.

One of the rarest breeding bird species in the Oak Openings is the lark sparrow. Perhaps two dozen pairs of this handsome sparrow occur in a good year. Lark sparrows also prosper by changes wrought by controlled burning. Southern specialty birds at their northern limits are also of interest. Resplendent blue grosbeaks decked in hues of rich indigo set off by cinnamon wing bars are found no farther north. Another southerner is the summer tanager. This species needs open oak woodlands, and management practices have benefited this brick-red beauty.

Young but complex, Oak Openings habitats are always interesting to explore and offer finds that can’t be made elsewhere in Ohio.

Eastern hognose snakes are at home in the sandy soils of the Oak Openings. This toad-eating species is a dramatic bluffer; hissing, striking, and finally playing dead if the former strategies fail to intimidate.

Resthaven Wildlife Area

ACREAGE: 2,272

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Wildlife

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.ohiodnr.com/Home/wild_resourcessubhomepage/

WildlifeAreaMapsRepository/tabid/10579/Default.aspx

http://www.ohiobirds.org/birdingsites/showsite.php?Site_ID=33

Before settlement, Castalia Prairie stretched nearly to Sandusky, merging with vast prairie wetlands buffering Lake Erie’s western basin. The only significant surviving remnants are in Resthaven Wildlife Area. Prior to acquisition by the Ohio Division of Wildlife in 1942, the prairie was mined for marl, a limey mineral formed by artesian waters and used in the cement-making business. Evidence of marl extraction can still be seen in the form of linear excavations separated by elevated berms.

In spite of past disturbances, prairie plants abound. Species in the sunflower family are important prairie components, and many of them are obvious in summer and fall. Gray-headed coneflower, prairie-dock, whorled rosinweed, and black-eyed Susan all shoot forth yellow blooms that attract armies of insects. Of Ohio’s thirteen species of milkweeds, eight can be found here. Preeminent is Sullivant’s milkweed, which was discovered in Ohio and named for its finder, William Sullivant of Columbus. Like most milkweeds, its sweet nectar lures scores of butterflies.

There are some must-see botanical events in Ohio. The mid-May blooming of thousands of white lady’s-slippers in Castalia Prairie is one of them. The Ohio Division of Wildlife manages this endangered orchid by regularly burning the meadows in which they occur. Like many prairie plants, white lady’s-slippers orchids co-evolved with fire and need regular burns to survive and thrive.

Brushy wetlands and open meadows of Resthaven Wildlife Area support many species of birds, both breeders and migrants. In March, numerous American woodcock create a spectacle. At dusk, these long-billed sandpipers begin their odd courtship rituals. The male stakes out a patch of turf and emits short nasal peent calls. Eventually he launches skyward, circling high above the female observing from the ground, all the while emitting peculiar chirping sounds. For the finale, the woodcock drops rapidly earthward, creating squeaky chirping sounds from air rushing through specially shaped primary wing feathers.

In 1998 a new species of moth, Spinopogon resthavenensis, was discovered in prairie remnants at Resthaven Wildlife Area. It is drab and obscure—easily overlooked, and few lepidopterists would have recognized it as different. It tells a story, though; even in a well-explored place like Ohio, flora and fauna remain undiscovered and unstudied.

Indian grass, shown here, and big bluestem together form the classic components of Eastern tallgrass prairie. Moisture-seeking roots may penetrate eight feet into the ground.

Numbers of yellow-breasted chats, our largest warbler species, inhabit Resthaven Wildlife Area’s prairie openings. These avian oddities have one of the largest repertoires of any songbird.

Blazing-star, goldenrod, boneset, and sunflowers create a colorful palette amongst prairie grasses in late summer at Resthaven Wildlife Area.

White lady’s-slippers need fire to maintain a suitable habitat. The Ohio Division of Wildlife manages for this rare orchid by periodically burning the meadows in which they occur.