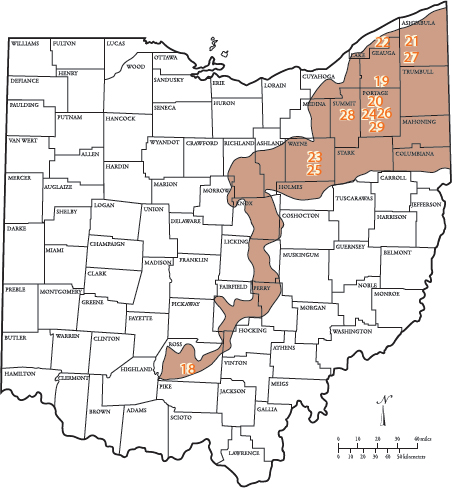

Glaciated Allegheny

Plateaus

Buzzards Roost Nature Preserve (18) • Fern Lake and Lake Kelso (19) • Gott Fen State Nature Preserve (20) • Grand River Terraces (21) • Hell Hollow Wilderness Area/Paine Creek Watershed (22) • Johnson Woods State Nature Preserve (25) • Kent Bog State Nature Preserve (24) • Killbuck Marsh Wildlife Area (23) • Mantua Bog State Nature Preserve (26) • Morgan Swamp (27) • Singer Lake Bog (28) • Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve (29)

Buzzards Roost Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: Approximately 1,200

OWNERSHIP: Ross County Park District

ACCESS: Best entered at the western terminus of Red Bird Lane off Polk Hollow Road; take Polk Hollow Rd. south from U.S. Route 50 just west of Chillicothe.

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.rosscountyparkdistrict.com/

http://www.svbnc.org/Earl%20H.%20Barnhart%20Nature

%20Preserve.html

The Paint Creek Valley is a place of geological convergence. At Chillicothe, hills of the Allegheny Plateau begin their rise, and flat Illinoian and Wisconsin till plains—remnants of our last glaciers—trickle to a stop just west of town. Perhaps most conspicuous are massive walls of black shale rising high above the valley. The largest of these are Alum Cliffs and Copperas Mountain, rising 250 and 550 feet, respectively, exposing massive banks of shale from several geologic epochs.

In the midst of this geological wonderland is the more than twelve-hundred-acre Buzzards Roost Nature Preserve. A place of diverse forests, the site—acquired and protected only in the past five years—is not well known to outsiders. As would be expected, such a mammoth, diverse landscape holds tremendous biodiversity, and much remains to be discovered. A June 16, 2004, “Botanical Blitz” conducted by two dozen botanists found over 350 species of plants—in one day! Many were new records for the preserve. Over six hundred species of plants have been found so far, and eventually seven hundred or more species may be documented.

Ridgetops high above the Paint Creek Valley are timbered in black and chestnut oaks, along with a smattering of scarlet oak, black-gum, and shagbark hickory. As one proceeds downslope, soils become richer and more moist, and tulip tree, red oak, and American beech begin to dominate. Lush stream terraces are covered with box-elder, green ash, silver maple, and Eastern cottonwood.

Along with big, diverse woodlands come lots of birds. Basic biological data is still being collected, and more additions will be added to Buzzards Roost’s bounty, but the number of breeding birds currently exceeds eighty species. Many of these nesters are neotropical species that winter in the jungles of Central and South America. Included among their ranks are the perilously declining cerulean warbler, the stunning rose-breasted grosbeak, and a burst of understory brightness, the showy hooded warbler.

One of Ohio’s best remaining streams is Paint Creek, and protection of buffering Buzzards Roost has surely helped protect its water quality. About forty-five species of fishes live in its waters, including pollution-sensitive rarities such as sand darter and the Northern madtom. The latter is a tiny catfish capable of delivering painful stings with its sharp pectoral spines. All told, nineteen species of fishes listed as endangered, threatened, of special interest, or under investigation have been found in Paint Creek.

Buzzards Roost is on the western edge of the unglaciated Allegheny Plateau. Trees tolerant of poor, acidic ridgetop soils like chestnut oak range no farther west, where limestone bedrock pushes close to the surface and sweetens the soil. This preserve is also one of our largest contiguous tracts of woodland in Ohio’s central region. Visitors can experience a taste of the vast forests that cloaked presettlement Ohio and interesting flora and fauna that inhabit them.

Heavily forested bluffs and slopes of Paint Creek create a rugged wilderness setting just outside of Chillicothe.

One of six Ohio swallowtails, Eastern tiger swallowtails often course high in forest canopies, laying eggs and dipping earthward to nectar at favored flowers.

The diminutive Sullivantia is saxicolous, or rock-dwelling. It occurs on shaded limestone cliffs along Paint Creek near Buzzards Roost. This member of the Saxifrage family has historical roots in the state. Famed botanist William Starling Sullivant of Columbus discovered Sullivantia in nearby Highland County, Ohio.

Furtive and hard to observe, male Kentucky warblers deliver a chanting song reminiscent of galloping horse hoof beats.

Few birds are more secretive than the tiny, robin-sized Northern saw-whet owl. In 2003, a banding operation was launched at Buzzards Roost that has captured and banded over 110 owls to date.

Fern Lake and Lake Kelso

ACREAGE: 302

OWNERSHIP: Cleveland Museum of Natural History; Geauga Park District

ACCESS: Lake Kelso/Burton Wetlands open to public during posted hours; Fern Lake by permit through the Cleveland Museum of Natural History

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.cmnh.org/site/Conservation_NaturalAreas_Map

_FernLakeBog.aspx

http://www.geaugaparkdistrict.org/parks/burtonwetlands.shtml

Pristine wetland complexes like Burton Wetlands/Lake Kelso and Fern Lake have become very rare in Ohio. Thanks to protection efforts by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and Geauga County Park District, we can enjoy a northern bogscape in Ohio.

Glacial kettle bogs are one of our scarcest habitats. Prior to establishment of laws to protect wetlands, and the efforts of conservation organizations, most of our peatlands were either filled or mined for peat. A study published in 1992 showed that about 98 percent of Ohio’s bogs and fens have been destroyed in the past century.

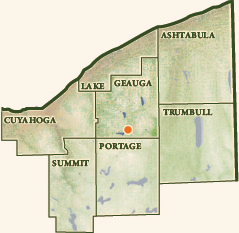

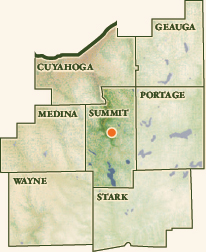

The 302 protected acres of Fern and Kelso lakes are part of a much larger system sometimes called the Cuyahoga Wetlands. Encompassing nearly one thousand acres, this region is dotted with small glacial kettles, swamp forests, and seepage meadows. Rarities abound, including the endangered American emerald dragonfly with its brilliant green eyes. This predatory insect is at the southern limit of its range here, with only a few known sites in Geauga and Portage counties.

At least twenty-nine species of state-listed rare flora have been documented at Fern and Kelso. Many are boreal relicts; travel to northern bog country and most would be common. About ten thousand years ago, in the wake of the retreating Wisconsin glacier, these plants would have been frequent in Ohio, too. The postglacier landscape was cool, boggy, and wide open—prime habitat for bog species. As the climate warmed, tundralike environments developed into deciduous forests. Today, specialized peatland flora only occurs in our best remaining bogs and fens.

Plants in the heath family dominate bog mats. A small shrub, leather-leaf, glosses up the carpets of Sphagnum moss in May, when it produces abundant racemes of small white flowers. Creeping along the surface is large cranberry, the same species elsewhere cultivated for its fruit. Of special note are small patches of the endangered small cranberry, only known from a few Ohio bogs. Of the twenty-one native Ohio heaths, seven are found only in peatlands and most are rare.

This is one of few Ohio sites that harbor pitcher-plants. Carnivorous plants like bladderworts and sundews, pitcher-plants are typical of bogs and evolved a meat-eating lifestyle to survive in nutrient-deficient substrates. Through different mechanisms, these plants lure insects to their modified leaves, which serve as killing traps. Once snared, the plant slowly digests the animal and extracts its proteins and nitrogen.

A tiny carnivore, sphagnum sprites are less than an inch long. This damselfly is rare and local in Ohio peatlands.

Beautiful Lake Kelso seems more apropos of northern Michigan or Canada than Ohio. Concentric bands of vegetation, layered in different plant communities based on substrate and water depth, ring the lake. Extending farthest into the depths is fragrant water-lily, which produces creamy-white floating blossoms.

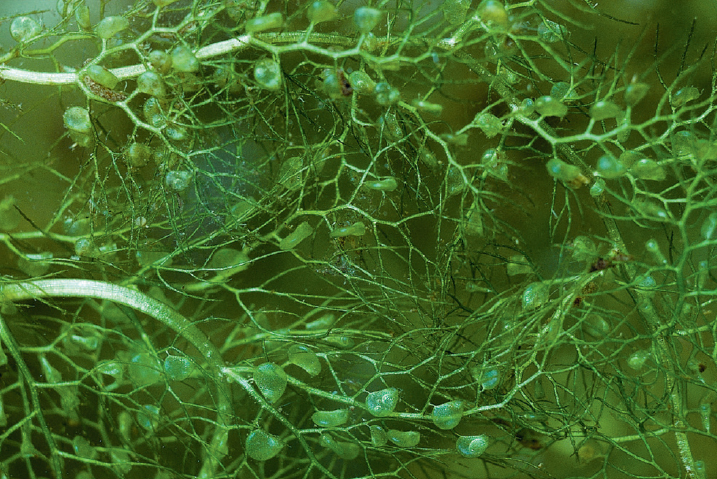

Bladderworts are the largest group of carnivorous plants in the world. Six species occur in Ohio, including this common bladderwort. Their roots are heavily beset with tiny bladders, which trap aquatic animals.

The waterthrush genus name Seiurus means to “wave tail.” Northern waterthrushes incessantly bob their rear ends as they forage along the margins of boggy areas. They are common Ohio migrants, but very rare as breeders.

The City of Akron also owns land in the Cuyahoga Wetlands. As part of a visionary effort to protect a major water source, the Upper Cuyahoga River, this municipality began acquiring large chunks of land buffering the stream. Included in its holdings is the best white pine bog in Ohio. A soupy, hard-to-traverse morass, this rare wetland supports towering old-growth pines along with many rare plants.

Protection of Lakes Fern and Kelso and other areas of the Cuyahoga Wetlands has only been possible due to the efforts of several organizations. The Cleveland Museum of Natural History, The Nature Conservancy, Geauga County Park District, and the City of Akron have forged an alliance of partners working together to conserve one of Ohio’s most biologically significant regions.

Gott Fen State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 44

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: By permit only

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/permitonly.htm

Fens are wetlands created by outflows of mineral-rich artesian springs. Water that has percolated through subterranean limestone aquifers, becoming infused with calcium bicarbonates, eventually is forced to the surface by hydrostatic pressure. Exploding from pores in the earth’s surface, the chilled water rushes along small rivulets and saturates soils in the vicinity.

The end result is the fen meadow: lush, densely vegetated landscapes filled with specialized plants. The combination of cold root-zone temperatures, thoroughly saturated and highly alkaline soils, and sizzling aboveground summertime heat precludes most plants that didn’t coevolve with fen habitats.

Baltimore checkerspots can be found in fens and wet meadows. The young caterpillars band together within a communally constructed silken, bagwormlike nest.

Showy lady’s-slippers are North America’s largest terrestrial orchid. The huge, saclike flower has a large opening that permits bumblebees to enter and pollinate. Look, but don’t touch; handling the foliage can cause dermatitis similar to poison ivy. This orchid is threatened in Ohio; only five populations are known.

Some ecologists classify Ohio fens into two types: prairie fens and boreal fens. Gott Fen is among the latter; many of its plants are northerners at the southern limits of their ranges in Ohio.

To a botanist, few Ohio habitats are more interesting than fens. These wetlands are loaded with rarities, many of which grow in no other habitat. Gott Fen has at least twenty-three species of state-listed rare plants. Perhaps the most significant is bayberry, a small shrub with whitish waxy berries. Bayberry is endangered and only occurs in one other nearby locale. Bayberries, including this species, are sometimes used in candle-making.

Another noteworthy rarity is our smallest dogwood, bunchberry. This tiny shrublet stands but six inches tall and is endangered in Ohio. While wide-ranging and abundant across boreal forests of Canada and the northern United States, it barely reaches our latitude. It is thought that bunchberry is intolerant of soil temperatures with an average mean of greater than sixty-five degrees; thus most Ohio habitats are too warm.

Adequately protecting fens is difficult. While the fen proper can be purchased and managed, that is but part of the equation. Groundwater that feeds the hydrology of these rare wetlands is derived from expansive underground aquifers, and waters that eventually percolate into the fen may have entered the ground miles away. Thus, alteration of far-off habitat may adversely impact the quality and quantity of water feeding the fen.

The diminutive grass-of-parnassus brightens the fen meadows in mid to late summer. This saxifrage species is habitat-specific. It only occurs in saturated alkaline soils.

Grand River Terraces

ACREAGE: 745

OWNERSHIP: Cleveland Museum of Natural History

ACCESS: By permit only

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.cmnh.org/site/Conservation_NaturalAreas_Map_

GrandRiverTerraces.aspx

During the Pleistocene, misshapen lobes of ice jagged off the advancing face of the Wisconsin glacier, drilling valleys into the rugged landscape of northeast Ohio. When these icy spurs shoved against impervious sandstones not far south of Lake Erie, glacial progress halted. The results were valleys eroded into softer shales abutted by more resistant rocks. The odd, sinuous course of the Grand River is the result of this glaciation; the river was forced into a valley created by glacial scouring.

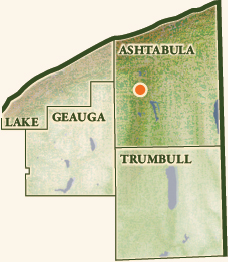

Located in our largest county, Ashtabula, the Grand River Terraces stretches for about a mile along the Grand River. Acquisition began in 1982 when the Cleveland Museum of Natural History took possession of the original seven hundred acres. The property contains excellent examples of floodplain forests and vernal pools. The finest hemlock swamp in Ohio occurs here.

Hemlocks are northern conifers and, in Ohio, almost always are found on steep slopes of cool ravines. Their occurrence in flat, swampy ground is rare, and as befits such an unusual habitat, a number of rare plants also are found in hemlock swamps. Among the scarcest is an odd member of the rose family, robin-run-away. This unroselike oddity creeps low over the ground, and the terraces host Ohio’s largest population.

Five species of orchids have been recorded thus far. One of the most interesting is crane-fly orchid. The insect-shaped blooms are noctodorous—they produce a fragrance at night. The aroma attracts certain moths, and the shape of the flower forces pollen into contact with their fuzzy eyes.

Woodland pools harbor noteworthy breeding populations of at least three species of mole salamanders. Jefferson, silvery, and spotted salamanders migrate to these vernal wetlands in early spring, mate, drop egg masses, and return to subterranean haunts where they spend most of the year.

The streamside habitats of the Grand River Terraces directly protect the water quality of one of Ohio’s most pristine rivers. The ninety-eight-mile-long Grand River drains 712 square miles of northeast Ohio, and a thirty-three-mile section has been named a state scenic river. Twenty-three miles are designated as wild, one of few Ohio streams to merit that classification.

Because corridors along the Grand River have been protected, many sensitive aquatic organisms still flourish. Riffles in the terraces support thriving freshwater mussel beds that include at least eleven species, among them the rare black sandshell and round pigtoe. Not far downstream of the terraces, a bizarre aquatic plant, riverweed, grows in midriver rapids. This mosslike plant is extremely sensitive to water-quality degradation, and the Grand River supports Ohio’s only population.

Turk’s-cap lilies are amongst Ohio’s most spectacular wildflowers. Reminiscent of a Turkish turban, this lily occurs in alluvial soils of floodplain forests.

Grand River Terraces is an excellent example of a Lake Plain hemlock swamp. Lush beds of cinnamon and royal ferns grow on hummocks surrounding the woodland pools.

Sand darters are found on clean, sandy stream bottoms. This darter has declined significantly in Ohio and is listed as a species of concern. Excessive siltation of our waterways has eliminated this species from many of our streams.

In total, the Grand River Terraces and other riverine habitats in the watershed support at least fifty state-listed rare plants, about one hundred species of breeding birds, twenty-eight species of amphibians and reptiles, and seventy-four fish species—incredible biodiversity by any standard, making the Grand River Terraces and the Grand River one of Ohio’s most significant natural resources.

Hell Hollow Wilderness Area/Paine Creek Watershed

ACREAGE: 783

OWNERSHIP: Lake County Metroparks

ACCESS: Open to public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://lakemetroparks.com/select-park/hell-hollow.shtml

Steep, deep ravines in the Paine Creek Watershed harbor boreal flora unlike most of Ohio. Lying in the middle of the Snow Belt, it receives an average of 106 inches of snow annually. Habitats here resemble coniferous woodlands of Canada. Gorges such as Hell Hollow host dense stands of hemlock, and understory shrubs include rare northern species such as hobblebush. Adventurers seeking the cool ravine bottoms can hike down a 262-step wooden staircase.

Some of the standout rarities of the region are birds. A potpourri of unusual breeders occupies hemlock glens in Hell Hollow, such as black-throated green; Canada, magnolia, and Blackburnian warblers; hermit thrush; and winter wren. The last, a four-inch-long ball of feathers, sings one of the most complex songs in the bird world. This tune seems to perfectly match the shadowy beauty of the hemlock gorges.

Because streamside habitats have been well protected in the Paine Creek drainage, aquatic habitats are outstanding. One of two species of rare dragonflies found along local watercourses is Uhler’s sundragon, an Ohio endangered species. Rather dull except for brilliant green eyes like others in the emerald family, adults often shun streamside haunts and forage in sunny forest openings.

The claybank tiger beetle is one of nineteen species of tiger beetle occurring in Ohio. Shale banks along Paine Creek support the only known Ohio populations of this rare insect.

Dense forests buffer the steep slopes along Paine Creek, protecting the water quality of the stream. Biodiversity is exceptionally high in this watershed because much of the adjacent lands have been protected.

Riffle snaketails, so named for their serpentlike abdomen, are intimately tied to streams. The adults loaf on rocks in the current, making regular patrols over the water to capture small insects and ward off rival males. This dragonfly is threatened in Ohio, and Paine Creek supports one of few populations.

Dragonflies serve as excellent barometers of stream health. Although adults aren’t necessarily water-dependent, larvae are. Often called nymphs, dragonfly larvae spend anywhere from a few months to several years in the water, feeding and growing. Like miniscule aliens from a horror movie, they sport ejectable mandibles. In a flash, the nymph lunges its jaw forward an extraordinary distance and seizes unsuspecting prey.

Some 360 million years ago, conditions here were far more aquatic than today, although water remains a conspicuous feature. During the Devonian period, a shallow sea covered the land, and as it receded, shale deposits were left behind. Today, an impressive bank of Chagrin Shale can be seen from Hell Hollow Wilderness Area. The Paine Creek Watershed also contains a number of fine waterfalls. About 250 million years ago the first dragonflies took wing, and members of the Odonata have probably been hunting the waters of Paine Creek’s watershed ever since.

Breeding dark-eyed juncos are rare and locally distributed in northeastern Ohio. Hell Hollow’s ravine supports many pairs of this species.

Five species of dace inhabit Ohio streams. Breeding in clear pools, redside dace populations are found along the unglaciated Allegheny Plateau.

Johnson Woods State Nature Preserve

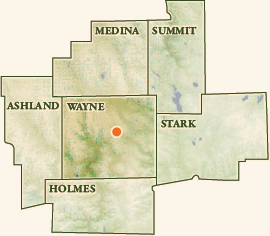

ACREAGE: 206

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/location/johnson_woods/tabid/

898/Default.aspx

There are precious few Ohio woods that harbor trees over three hundred years old, but this site is one. A walk through the giants at Johnson Woods is sure to inspire awe among visitors. Some of the trees climb well over 130 feet skyward and have girths the size of big dinner tables. Once, over 90 percent of Ohio was covered with similar forests.

The trees at Johnson Woods, old and mature when Ohio achieved statehood in 1803, stood firmly rooted when the first pioneers swept into the region. It’s likely that gray wolves and elk—creatures long gone—once roamed in their shade. To Jacob Conrad, the original owner of Johnson Woods, such a landscape would have been mundane in 1823 when he made his claim. Little did he know that, less than two hundred years later, only a tiny fraction of a percent of Ohio’s primeval timber would remain.

The largest trees are red and white oaks, and shagbark hickory. Some of these leviathans are near the end of their lifespan. As upland oaks and hickories gradually fade from the scene, faster-growing and shorter-lived species that flourished in the shady understory dominate. Sugar maple and American beech will one day be the principal tree species at Johnson Woods. This shift in plant communities is known as ecological succession and is inevitable. Fire was far more frequent in presettlement landscapes than is widely recognized. Burns did not affect thick-barked, heat-resistant oaks and killed softwoods like maple. People have a natural aversion to wildfires, though, and fire suppression has become the norm in modern times, accelerating the shift from oaks to maples.

Low-lying woodland pools are ringed with pin and swamp white oak, red maple, and green ash. In the wettest areas is an interesting shrub, buttonbush. A member of the coffee family, buttonbush is thick with balls of white flowers in summer. Butterflies, especially silver-spotted skippers, swarm to the blooms seeking nectar.

Visit Johnson Woods in early May, before leaves have yet to mask the true dimensions of the grand trees. The forest floor will be a carpet of wildflowers: yellow trout-lilies, large-flowered trillium, spring-beauties, wild geraniums, and dozens of others. Newly arrived neotropical birds like scarlet tanager, yellow-throated vireo, and great crested flycatchers send down their melodies from the canopy. Then imagine that thirty-seven thousand square miles of Ohio looked like this only two hundred years ago.

We owe the existence of Johnson Woods to the generosity of Clela and Andrew Johnson and their family, who ensured that this 206-acre patch of primeval timber remained uncut. Many of the trees here are over 300 years old and tower to 120 feet in height in this outstanding woodlot.

Large-flowered trillium was declared the Ohio state wildflower in 1986. Fresh blooms are creamy white; as the flower ages, it becomes tinged with pink. White-tailed deer enjoy snacking on trillium and other lilies and have caused localized population declines.

This is the largest woodpecker remaining in North America. It favors mature forests. Pileated woodpeckers excavate large, ovalshaped nest holes that are utilized by many other animals.

Kent Bog State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 42

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/location/KentBog/tabid/900/Default.aspx

Ohio bogs were created about twelve thousand years ago, spawned during the retreat of the Wisconsin glacier. Enormous ice chunks calved from the glacier’s face created gigantic divots in soft, mucky soil, and these depressions filled with water.

Over time, plants colonized the kettle lakes, and Sphagnum mosses formed thick layers. Eventually, Sphagnum proliferate to the point where it became the dominant substrate. As a byproduct of its growth, these spongy mosses exude acidity, thus influencing the types of plants that can grow within the bog. Most plants aren’t acid-tolerant, and many of those that are tend to be rare in Ohio and confined to bogs.

After thousands of years, plants eventually squeeze out open water and overtake the kettle lake. The amount of time required for this ecological process varies and is dependent upon the size and depth of the lake, but ultimately plants will win out.

Kent Bog is far along in its life. No open water remains and the bog mat is thickly overgrown with tamarack and gray birch. The gnarly tamarack forest at Kent Bog is the largest stand found this far south. Interesting shrubs form dense thickets in the bog, including catberry and winterberry, two of the three native Ohio hollies. Eight-foot-tall hedges of highbush blueberry produce bounties of sweet berries in summer. The most characteristic bog shrub is leather-leaf, which grows in profusion and is covered with bell-shaped white flowers in May.

Several rare sedges grow on wet mossy hummocks in Kent Bog, and the showiest is tawny cotton-grass. Long, plumelike bristles extend from their seeds, forming billowy cotton candylike tufts. Much less obvious and rarer yet is the spindly few-seeded sedge, only known in a few Ohio bogs.

Unusual moths often occur in kettle bogs, and the rarest known at Kent Bog is the graceful underwing. Endangered in Ohio, this night-flier’s larvae feed on blueberry leaves. Underwing moths are drab and undistinguished—until startled. When threatened, they quickly flash their underwings, which are normally concealed. Bright orange-yellow patterns explode into view like giant eyes, frightening off predatory birds.

It’s interesting to ponder changes in Ohio’s environment when ensconced among the tamarack stand at Kent Bog, surrounded by northern plants in this glacial relict habitat. Only ten thousand years ago—an incalculable iota of the earth’s 4.5 billion years—much of Ohio looked like this. Boreal forests of tamarack and spruce cloaked quaking peaty soils, and plants that we now consider rare and protect were commonplace. Long-lost animals like mastodon, saber-toothed tiger, and muskox ranged the landscape. At Kent Bog, visitors can glimpse our glacial past.

This site is formally known as the Tom S. Cooperrider Kent Bog State Nature Preserve, in honor of the Kent State University botanist who has played a major role in describing Ohio’s flora.

Before dropping from the trees in late fall, the needles of tamarack, our only deciduous conifer, turn a striking golden yellow. In Ohio, tamarack is confined to peatlands. The small cones shown here are valuable food for squirrels and birds.

Choked with tamarack and gray birch, Kent Bog contains the largest southern stand of tamarack in the United States.

Saddleback caterpillars are small moth larvae that look like they are wearing tiny lime-green horse blankets trimmed in white. Look, but don’t touch. Admire them from afar. Stiff clumps of bristles are stinging spines. These hairs can deliver perhaps the most powerful sting of any North American caterpillar.

A widely recognized symbol of wetlands, great blue herons are common throughout Ohio. Their colonies of nests are known as rookeries and can range in size from a few nests to several hundred.

Killbuck Marsh Wildlife Area

ACREAGE: 5,521

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Wildlife

ACCESS: Open to public during posted hours. Some areas may be access restricted.

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/Home/wild_resourcessubhomepage/

WildlifeAreaMapsRepository/tabid/10579/Default.aspx

Modern-day floods pale in comparison to the gully-washers of twelve thousand years ago. Meltwaters from enormous ice sheets of the retreating Wisconsin glacier ripped through the landscape in torrents, carving massive channels and creating the vast Killbuck Valley.

The broad, poorly drained valley is filled with wetlands—our largest complex south of Lake Erie. Two types of plant communities dominate: marshes and swamps. Marshes are open wetlands characterized by herbaceous plants like cattails, arrowheads, bulrushes, and water-lilies. Swamps feature woody plants and shrubs, like buttonbush and trees such as green ash, silver maple, swamp white oak, and cottonwood.

Birds rule at Killbuck. Excellent numbers and diversity of waterfowl peak in March, when wetlands are rejuvenated by spring floods. It’s possible to find twenty-seven of Ohio’s thirty-five species of regularly occurring geese, swans, and ducks—in one day! Hundreds of American wigeon are eagerly picked through by birders seeking the occasional and far rarer Eurasian Wigeon. American wigeon are fun to watch. These colorful dabbling ducks are kleptoparasites; they frequent deeper waters with lesser scaup, redhead, and ring-necked ducks, snatching tasty underwater plants from these diving ducks when they surface.

Four-foot-tall sandhill cranes are on the upswing in Ohio, breeding in perhaps a dozen locales. Until 1987, they hadn’t bred in the state for nearly one hundred years. That year, a pair successfully nested at Killbuck, and cranes have bred here ever since, expanding to several nesting pairs.

The only eastern cavity-nesting warbler, prothonotary warblers inhabit swamp forests. Their rich lemon-yellow plumage is practically luminescent. The presence of suitable nesting cavities is a limiting factor in prothonotary warbler distribution. The numerous standing dead trees in the swamps of Killbuck support some of the best populations in Ohio.

Rails are chickenlike marsh birds with laterally compressed bodies that allow them to easily slip through thick stands of cattails. Virginia rails are far easier to hear than see. They emit a metallic kiddick kiddick series of notes.

Killbuck’s wetlands support many significant breeding birds. Tracts of swampland dead timber are riddled with cavities, and red-headed woodpeckers are frequent. So beautiful are these crimson-headed birds that they inspired the “Father of American Ornithology,” Alexander Wilson, to study birds.

Strange sounds emanate from marshy tangles, produced by chickenlike sora and Virginia rails, pied-billed grebes, common moorhens, and least bitterns. Obvious and plucky marshland songsters are marsh wrens. Producing liquid gurgles that sound like a flute being played underwater, marsh wrens are common in cattail and bur-reed colonies. All of these birds have declined due to habitat loss—over 90 percent of Ohio’s wetlands have been destroyed.

Aerialists supreme, masses of dragonflies patrol Killbuck wetlands hunting tiny insects. Prominent are skimmers, the largest group of Ohio dragonflies with thirty-seven species thus far recorded. Kaleidoscopelike patterned wings of widow skimmers, twelve-spotted skimmers, and common whitetails shimmer in the sunlight as these insects dart and jag with impossible speed, snapping up gnats and mosquitoes. Jumbo swamp darners also occur; these giants measure three inches and are our largest Ohio dragonfly species.

Wings fill the air at Killbuck, and those with an interest in creatures that fly won’t be disappointed.

In 1986, the Ohio Division of Wildlife reintroduced 123 river otters in four locales in eastern Ohio. Their recovery since that time has been swift and successful—an estimated five thousand animals roam the state today, and Killbuck is one of the best places to see one.

Mantua Bog State Nature Preserve

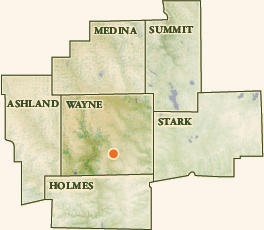

ACREAGE: 44

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: By permit only

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/dnap/permitonly/tabid/863/Default.aspx

This small preserve is rich in rare flora and fauna. Mantua Bog is a classic example of a boreal fen; many of the plants have strong northern affinities and are at their southern limits here. Although open fen meadows are but a few acres, they are packed with unusual plants. At least twenty-five state-listed rare plants have been found in the preserve.

Thick, spongy hummocks of Sphagnum moss create lush specialized substrates for plenty of odd plants. While even hardened botanists are spooked by the daunting prospect of learning sedges, this group of plants is interesting and ecologically important. The genus Carex is the largest group in the family, with about 155 species reported in Ohio. Many sedges are habitat-specific and excellent ecological indicator species, like little yellow sedge. Its bristly fruit looks like tiny maces, the medieval weapon used by knights of yore. This rare sedge grows only in fens and other alkaline wetlands. Many other sedges add to the floristic composition of Mantua Bog.

One of Ohio’s rarest plants grows in shrubby openings in the fen. Dragon’s-mouth is a gorgeous, magenta-flowered beauty and one of North America’s showiest orchids. In a good year, perhaps a dozen or two dragon’s-mouths appear, and Mantua Bog supports the only known Ohio population. Management activities have helped this orchid to survive, but its existence is tenuous. Although most Ohioans will never see this plant in the wild, at least in their home state, many might be heartened to know that such a beautiful botanical still persists.

Dragonflies abound in Mantua Bog and vicinity, including some rare and local species. By far the most unusual is the brush-tipped emerald. Each end of this dragonfly is an eye-catcher. The front is capped with two enormous brilliant green eyes, each containing thousands of individual facets. Each facet is the equivalent of a tiny eye; woe to the prey that falls into view of a hungry brush-tipped emerald. The emerald’s posterior is adorned with a pair of ferocious-looking hooks, or claspers. These are used to hold the female in place during mating. This endangered dragonfly is only known from Mantua and two other Ohio locales, the southernmost known populations.

In late summer, the fen meadow at Mantua Bog is covered with ferns, asters, and joe-pye-weed. The reds of poison sumac add to the riot of color.

With brilliant green eyes, state-endangered brush-tipped emeralds can be found at Mantua Bog. Almost all Ohio emeralds are uncommon or rare.

Mantua Bog supports the only known Ohio population of dragon’s-mouth orchids. Habitat management at Mantua has helped this orchid to survive.

Although small, Mantua Bog is significant, a living museum preserving relicts rare or nonexistent elsewhere in Ohio. Protection of sites like this is critical to conserving our state’s overall biodiversity.

Morgan Swamp

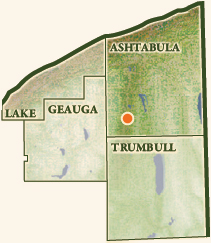

ACREAGE: Approximately 1,000

OWNERSHIP: The Ohio Chapter of The Nature Conservancy

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.nature.org/wherewework/northamerica/states/ohio/

preserves/art3029.html

Gazing upon seemingly pristine Morgan Swamp, it’s difficult to imagine the rough history of these tranquil marshes and swamps. The wetlands set on largely impervious clay layers up to fifty feet deep, deposits from twelve millennia ago when this area was covered by a glacial lake. Beginning in the 1850s, loggers began removal of virgin timber that blanketed the swamp, and by 1880 all the trees had been cut. Opening the wetlands to sunlight created drier conditions, and farmers exacerbated drainage efforts in an attempt to grow crops. Fires regularly raged, furthering deteriorating the marsh. Morgan Swamp was described by Lawrence Hicks, one of Ohio’s early chroniclers of natural history, as covering about three thousand acres in the early 1930s.

But nature is resilient, and after cessation of logging and farming efforts, Morgan Swamp began to recover. In 1985, the Ohio chapter of The Nature Conservancy began to acquire land here, and has built the preserve into one of Ohio’s most expansive privately protected natural areas. Today, the area looks much as it did before European settlement, excepting one sad loss. Before logging, a twelve-hundred-acre primeval hemlock swamp filled much of this low-lying basin, and the giant hemlock were among the first trees harvested. Consequently Ohio lost what may have been our best example of an exceptionally rare habitat.

Beaver have aided greatly in wetland restoration. These large rodents, which can grow to seventy pounds, are tireless workers and brilliant engineers. Relentlessly pursued for their valuable pelts, beaver were extirpated in Ohio by the 1830s. Their reappearance a century later was first recorded in Ashtabula County in 1936. Today they are once again common and creating wetlands. Intricate dams pool water and create a variety of wetland habitats that greatly increase biodiversity.

Morgan Swamp is for the intrepid. The vast, flat terrain pocked with soupy wetlands and tangled vegetation doesn’t lend itself to easy navigation, and a compass is recommended. The effort pays off, though—rare plants hard to find elsewhere in Ohio grow on elevated hummocks and in boggy quagmires. At least fifteen state-listed plants have so far been found, and other discoveries await. The rarest is Clinton’s wood fern. Found nowhere else in Ohio, this elegant beauty is a northerner, barely nipping into northeast Ohio. There are eighty-five species of ferns documented in the state, and this group is an important component of forest ecology. Other plant rarities include wild calla, robin-run-away, and pipsissewa.

Spatterdock, marsh fern, and soft rush bedeck a wetland at Morgan Swamp. The dwelling of nature’s ecological engineer juts in the background—a beaver lodge. Beaver play a vital role in creating wetlands, and their efforts benefit an enormous diversity of plants and animals.

Many of the bogs and fens in which the spotted turtle occurred have been destroyed. Always hard to find, they forage under the bog mat.

Two mammals evince the wildness of Morgan Swamp. There are recent records of both black bear and bobcat, former symbols of Ohio wilderness that are now rare. The former are on the increase, especially in this area where émigrés from expanding Pennsylvania populations turn up. The latter, our only extant wild cat, is more common than thought. Little felines—a big male is forty pounds—they are secretive and more likely to be heard caterwauling in the breeding season than seen.

One of Ohio’s last remaining wild streams flows through Morgan Swamp: the Grand River, which ultimately flows into Lake Erie. Dedicated as a scenic and wild river in 1974, its clean waters harbor exceptional aquatic life. Several rare animals sensitive to water-quality degradation survive in this stretch of river. Oddest of all may be the endangered Northern brook lamprey. Primal snakelike fishes, six native lampreys occur in Ohio streams; none are common. Adult brook lampreys don’t feed; they exist only to mate and reproduce. Other species are parasitic, attaching to host fish via suckerlike mouths by which they grind openings and extract fluids.

Star-nosed moles are almost completely subterranean and voraciously pursue small prey to fuel their unquenchable metabolisms. Like many moles, they are superb swimmers and often occur in wetland habitats.

The wild lands of Morgan Swamp play a key role in preserving rare biodiversity of northeastern Ohio, including flora and fauna seldom encountered elsewhere. Protection of this area also plays into the big picture of preservation of the Grand River watershed, one of Ohio’s last great places.

The crimson bull’s-eye center of the crisp white flower renders painted trillium unmistakable. Don’t expect to see this dazzler in Ohio. A species of northern woods, our showiest trillium barely enters northeastern Ohio.

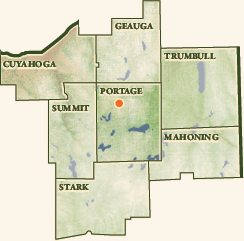

Singer Lake Bog

ACREAGE: 344

OWNERSHIP: Cleveland Museum of Natural History

ACCESS: By permit only

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.cmnh.org/site/Conservation_NaturalAreas_Map_SingerLake-Bog.aspx

The tale of Singer Lake is one of Ohio’s great stories of preservation. Among the state’s most significant wetlands, this bog went largely unexplored until the late 1980s despite being in a populous region. Staff of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History made their inaugural visit in 1989. That day, they found the first Ohio record of variegated orange moth. A day-flier, this gorgeous insect depends on cranberry as a host plant—a rare species in its own right. This discovery opened the floodgates of amazing new finds. About forty state-listed rare plants have been documented to date, along with several rare animals.

The bog is vast and intimidating. As with any good peatland, getting around isn’t easy, and the careless may drop through the quaking Sphagnum mat like an opened trapdoor. Acres of large cranberry carpet spongy ground, and this wetland supports Ohio’s largest stand of leather-leaf, a small bog shrub.

On June 1, 2000, intrepid entomologists found two rare dragonflies at Singer Lake: elfin skimmer and chalk-fronted corporal. The tiny skimmer was known only from two other locales. Also endangered, the corporal find was even more incredible. In all, sixty-seven species of dragonflies and damselflies have been found at Singer Lake—perhaps the richest diversity in Ohio, proof of the outstanding quality of these wetlands.

Aquatic plant communities further attest to the pristine nature of Singer Lake. Two endangered species, grass-like pondweed and spotted pondweed, grow in the lake’s deep waters. Pondweeds play important ecological roles: fish hide in their dense tangles, insects utilize them for food and shelter, and wetland birds eat the kernellike fruit. They are sensitive ecological indicators, and most have declined alarmingly in Ohio. These imperiled plants require clear waters to photosynthesize; murkiness caused by excessive sediments quickly eliminates them. No group of water plants has been harder hit by pollution. Of the twenty-three pondweed species recorded in Ohio, ten are state-listed rarities and five are extirpated.

The elfin skimmer, the smallest dragonfly in North America, is endangered in Ohio. The females resemble large hornets.

Diverse and expansive, Singer Lake Bog harbors more rare species than any other Ohio bog. Finding unusual flora and fauna isn’t easy here; one misstep and an explorer might find themselves neck deep in Sphagnum peat.

Few intact relicts of Ohio’s postglacial peatland heritage remain. A well-researched 1992 paper published in the Ohio Journal of Science documented the loss of 98 percent of the bogs and fens that were present at the time of European settlement. The primary cause of destruction was draining and development. The Natural Areas program of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History worked diligently to save this exceptional peatland. Its labors were successful, and virtually the entire ecosystem is now under protection.

An unusual member of the gentian family, spring-blooming buckbean occurs in a handful of bogs.

A northern species, the racket-tailed emerald inhabits bogs and fens.

Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve

ACREAGE: 61

OWNERSHIP: Ohio Division of Natural Areas and Preserves

ACCESS: Open to the public during posted hours

WEB SITE RESOURCES:

http://www.ohiodnr.com/dnap/location/triangle/tabid/967/Default.aspx

About twelve millennia ago, massive ice sheets of the Wisconsin glacier were in full retreat, melting back to the north. At its southernmost extent, ice covered all but the rough hill country of southeastern Ohio. At the glacier’s southern face, occasional gargantuan blocks of ice calved from the sheer frozen walls, leaving great depressions. Water gradually replaced the melting ice, forming a small lake. At first the water was clean and cold and largely barren of life. In time, specialized flora colonized the lakeshores and eventually expanded into the water. Today, most of Ohio’s kettle bogs have long since vanished—filled in by vegetation.

Triangle Lake, because of its depth, is still relatively young in the cycle of a bog and offers a snapshot of Ohio’s kettle-hole history. Classic bog plant patterns can be studied here. The outer reaches of the kettle are swamp forest, with many red maples. Inside of that zone is tamarack, a deciduous conifer intimately associated with peat bogs. Closer to the lake are shrub zones filled with highbush blueberry, poison sumac, catberry, and other woody plants. Finally, ringing the open lake waters is an open bog mat, composed of various Sphagnum mosses.

Bog mats are wonderful, treacherous places. A misstep can land one neck-deep in water, or worse. The risk is worth it to adventurous botanists. Many interesting plants grow on the mat, such as the carnivorous pitcher-plants and sundews. Several bladderwort species grow in little pools amongst the moss. Also carnivorous, these tiny aquatic plants have roots covered with saclike bladders that serve as killing traps, sucking in and ingesting tiny animals.

Triangle Lake Bog is Ohio’s finest example of a glacial kettle hole. It is an excellent place to learn about the fascinating biology of bogs.

Shown here are two botanical carnivores, pitcher-plant and round-leaved sundew. These plants have evolved highly modified leaves that enable them to capture insects, which serve as their source of proteins and nitrogen.

Masked shrews, Ohio’s second smallest mammal, inhabit wetlands. Their bite injects mild neurotoxins to subdue prey.

Triangle Lake, Ohio’s finest kettle lake bog, supports an outstanding diversity of damselflies and dragonflies, many of which are very rare this far south. Among them are Hagen’s bluet and frosted white-face. These rarities require pristine waters and specialized habitats, and few such sites remain in Ohio.