Chapter 6

The Tough Questions

There is no other planet to which we can turn for help, or to which we can export our problems. Instead we need to learn to live within our means.

— Jared Diamond80

The earth’s atmosphere is becoming warmer. This warming is happening unusually quickly because humans are adding greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide, to the air. The effects of this accelerated warming will be at best expensive and disruptive. At worst they will bring life-threatening catastrophe, especially for the poorest people of the world.

It is too late to avoid all the harmful effects of global warming. But we can try to slow down the advance — to give ecosystems time to adapt, to reduce the threat to the world’s fresh water and food supplies, and to prepare people of all nations to cope with the changes as best as they can.

It makes sense, then, to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide we are putting into the atmosphere.

There are two obvious ways to do this:

Reduce the amount of fossil fuels we burn. We will have to stop using these fuels eventually anyway, because there is a limited supply of gas, coal and, especially, oil underground.

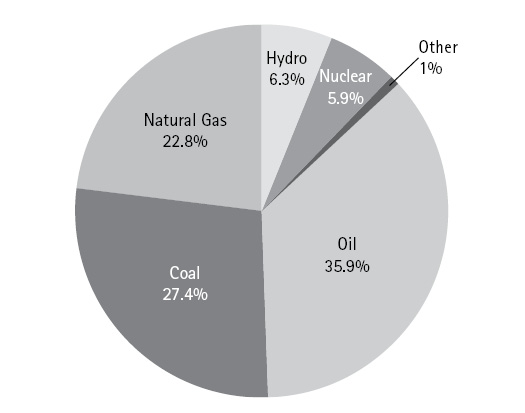

It is ridiculous to think we can simply stop using energy, but we can reduce our dependence on fossil fuels by using energy less wastefully and more efficiently, and by replacing fossil fuels with other sources of energy. We need to find other ways to run our vehicles and machines and heat our buildings. Right now fossil fuels supply more than 80 percent of the world’s energy, but the technology exists for us to obtain much more from renewable sources such as wind, solar, geothermal and biomass (fuels made from plants and other organic material).

Preserve and manage the world’s existing forests, and plant new forests. Forests are carbon sinks, so by maintaining healthy forests, we can actually remove some of the carbon dioxide that is building up in the atmosphere.

This is the logical response to the problem of global warming.

So what is standing in the way?

Where the World’s Energy Comes From82

We use a lot of energy, and our energy needs are growing quickly. This is partly because the world’s population is so big — 6.9 billion people and growing by 228,000 a day.83 Practices such as cutting down a dozen trees to build one house, clearing a field to keep a cow, burning coal to heat a room or cook a meal — even using a car to take one person to work — are no longer practical. More people, more homes, more cars and more industry equal more carbon dioxide emissions. Which means the problem is growing faster than we can keep up with it, because even while some try to reduce their energy consumption, others are using more and more. (Electricity generation, for instance, is expected to double by 2020, quadruple by 2060 and quintuple by 2100.84)

But the world’s growing energy needs are due to more than an expanding population. Societies of the industrialized world are based on producing and buying more and more goods, even though it is clear that the planet’s resources are limited. All the things that make up everyday life must be made, transported, used and thrown away, and each of these stages requires energy. We consume things, discard them, replace them, expand them — not just things we need but things we want, whether it is a new coat, house, car, computer or stereo. There is never enough because there is always a better or more stylish model, a new invention. Where you had one you can now have two, or more — cars, homes, phones, televisions.

Western culture, rapidly spreading throughout the globe, is based on acquiring stuff, and success is judged by whether one has more or better stuff than others. This is how economies grow and people and nations become rich. The whole idea of using less or producing less is unacceptable, so consumers are constantly encouraged to want more, buy more, use more.

Take the way we think about cars.

Next to electricity generation, one of the largest and fastest-growing sources of carbon dioxide emissions is road vehicles. Cars and trucks produce 30 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions. There are more than 500 million cars on the road today, and millions of new vehicles are manufactured each year.85 (If every family in India and China owned a car, there would be one billion more cars on the roads.86)

Early on we learn that cars are more than just a way to get from place to place. Cars symbolize freedom and status. People can see right away what kind of car you drive, and that tells them what kind of person you are. Are you rich and cool or geeky and shabby? Your car says it all.

Cars are so expensive that most people have to borrow money to buy one. (The average Canadian spends more money owning and operating a car than on housing, food or education.87) Yet many families in industrialized countries have two or more. Most are driven with just one person in them. We buy new cars even when the old ones still work, because manufacturers keep coming up with new colors, styles and accessories — cars with iPod docks and phones, air-conditioners and seat warmers, built-in DVD players, mini fridges, navigation systems and crash-warning sensors.

Most cars can already go about as fast as highways will bear, so car companies make models that are more powerful, heavier and bigger, with more accessories. Things like air-conditioners, power windows and seat warmers add to fuel consumption by making cars heavier or by using more electricity. (The average vehicle contains forty pounds of wiring alone, needed to connect all of the car’s electrical components.88) Automobile manufacturers know that heavy, powerful cars contribute directly to the rising level of greenhouse gases because they use more fuel, but they make them because people want to buy them. SUVs, which have been called one of the fastest-growing causes of global warming,89 burn 45 percent more fuel than regular cars (even though they are mostly used for everyday driving in cities), but they have bigger profit margins because they are basically fancy pick-up trucks.

Cars even determine where and how we live. Modern suburbs are built for people who have cars. Shopping malls are surrounded by parking lots. There are drive-through restaurants, banks and libraries. Multi-lane highways, tunnels, bridges, overpasses and parking lots are built and then widened to accommodate growing amounts of traffic. (Two-thirds of the land in downtown Los Angeles is used for streets, highways and parking.90)

While people in industrialized countries drive their cars to their homes in the suburbs, people in the developing world look on. Almost half of the world’s people still live near or below the international poverty line of two US dollars per day. Yet through television and advertising they can see what they are missing, and they want to have the same thing.

They say they should not be the ones to suffer because the climate is changing. It’s not the developing world that created global warming by burning huge amounts of fossil fuels in the first place. Surely the rich countries (20 percent of the world’s population using 80 percent of the world’s resources91) should pay for the damage they have caused, as well as reducing their own energy use, while the developing countries catch up.

But the idea of reducing greenhouse gas emissions is, for many, simply unacceptable. Powerful forces — governments and corporations — actively campaign against climate change action by trying to dispute the science and by playing on the fears of people who don’t want to put their good life at risk. (The biggest and most profitable company in the world, ExxonMobil, has refused to invest in clean technologies and instead pressures governments to resist action on global warming.) Governments in industrialized nations want to avoid the hard political decisions required to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Corporations fear that reducing the use of fossil fuels will mean reduced profits. Meanwhile, people in the developing world want their own economies to grow, which means using more energy.

It’s true that people are gradually using more energy from renewable energy sources, but so far these industries are far too small to fill the world’s needs, and each one has its drawbacks. Wind and solar power cannot be stored and must be backed up by other sources. And the initial setup costs are expensive. (It takes a lot of money and energy, for example, to make the photovoltaic panels needed to produce solar electric power.) The International Energy Agency predicts that by 2035 renewables (excluding biomass) will contribute only 7 percent of the world’s energy needs.97 Even nuclear power cannot fill the gap.

As well, renewable energy cannot be competitive unless consumers pay the true cost of burning fossil fuels. Governments often subsidize the fossil fuel industry — by providing money to help companies discover and develop new oil fields, by giving oil companies tax breaks. Subsidies mask the true price of the gasoline we buy at the pumps, at times making gas in the United States, for example, less expensive than bottled water. If people paid the true costs of transporting oil, cleaning up oil spills, the military costs of protecting access to oil, the cost to public health of smog and pollution produced by tailpipe emissions, fossil fuels would be far more expensive. Consumers would balk at paying so much of their incomes just to keep themselves warm and their appliances running, individuals and industries would use energy more efficiently, and the prospect of, say, using wind power or buying a hybrid car would be considerably more attractive.

Compared to reducing our dependency on fossil fuels, planting and preserving forests may seem to be an easy way to tackle global warming. Yet this, too, is not as simple as it sounds. Without careful supervision and management, only a fraction of replanted trees survive, so many more trees must be planted to replace those that have been cut. As well, it is difficult to recapture areas that were once forest because they have been used for farmland and cities. Sometimes the soils have been depleted and are no longer suitable for trees.

Meanwhile, our consumption of wood continues to grow. (In spite of the “paperless” promise of the internet, for example, we are using more paper than ever.99)

Tropical forests are especially difficult to preserve and replace, because they are such complicated ecosystems and because the people of developing countries have a growing need for cooking fuel, shelter and farmland. So much of the Amazon rainforest is being cleared for timber, cattle ranches and soybean farming that 40 percent of the remaining forest (the Amazon contains more than half of the world’s existing rainforests) is expected to be gone by 2050.100 Besides, developing countries deeply resent rich nations telling them not to cut their trees, when the greenhouse gas problem was created by the industrialized world in the first place. As one Brazilian official pointed out, “We’re not going to stay poor because the rest of the world wants to breathe.”101

80. Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (New York: Viking, 2005), 521.

81. Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture, www.leopold.iastate.edu; Worldwatch Institute, www.worldwatch.org.

82. Energy Information Administration, 2006 data, www.eia.gov/iea/overview.html.

83. Population Reference Bureau, www.prf.org.

84. International Energy Association, www.iea.org.

85. John Whitelegg, “The Global Transport Challenge,” Open Democracy, April 26, 2005; World Book 2001; Peter Gwynne, “Green Cars Move into Top Gear,” Physics World, July 2002.

86. Mark Maslin, Global Warming: Causes, Effects and the Future (Osceola, Wisconsin: Voyageur, 2002), 22.

87. Tim Grant and Gail Littlejohn, Teaching About Climate Change: Cool Schools Tackle Global Warming (Gabriola Island, BC: New Society, 2001), 52.

88. Globe and Mail, “To Lose Pounds, Even Wires Get Skinny,” June 2, 2005.

89. Linda McQuaig, It’s the Crude, Dude: War, Big Oil, and the Fight for the Planet (Toronto: Random House, 2004), 5.

90. Clive Ponting, A Green History of the World: The Environment and the Collapse of Great Civilizations (New York: Penguin, 1991), 213.

91. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Beginner’s Guide, 1994, www.unfccc.org/resource/beginner.html.

92. World Bank, “China Quick Facts,” web.worldbank.org.

93. Stephen Kurczy, “China energy use surpasses US. Who didn’t see that coming?” Christian Science Monitor, July 20, 2010.

94. “Changes in Vehicles per Capita around the World,” US Department of Energy, Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, April 5, 2010, www1.eere.energy.gov/vehiclesandfuels/facts/2010_fotw617.html.

95. Keith Bradsher, “China Outpaces U.S. in Cleaner Coal-Fired Plants,” New York Times, May 11, 2009.

96. World Bank, “China Quick Facts,” web.worldbank.org.

97. IEA, World Energy Outlook 2010, www.iea.org/work/2011.

98. Andrew Heintzman and Evan Solomon, eds., Fueling the Future: How the Battle Over Energy Is Changing Everything (Toronto: Anansi, 2003), 135.

99. Michael Williams, Deforesting the Earth (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 496.

100. Britaldo Silveira Soares-Filho et al, “Modelling Conservation in the Amazon Basin,” Nature, March 23, 2006.

101. Chicago Tribune, March 12, 1989, quoted in Williams, 499.