Many topics within economics relate to law. A large body of work in public economics, for instance, examines the effects of legally mandated government programs such as disability and unemployment insurance (Katz and Meyer 1990; Gruber 1994; Cutler and Gruber 1996; Autor and Duggan 2003); work on the labor market examines the effects of many types of antidiscrimination laws (Heckman and Payner 1989; Donohue and Heckman 1991; Acemoglu and Angrist 2001; Jolls 2004); and recent corporate governance research studies the consequences of corporate and securities law on stock returns and volatility (Gompers et al. 2003; Ferrell 2003; Greenstone et al. 2006). But, while all of these topics relate to law in some way, neither “law and economics” nor “behavioral law and economics” embraces them as genuinely central areas of inquiry. Thus an important threshold question for the present work involves how to characterize the domains of both “law and economics” and “behavioral law and economics.”

Amid the broad span of economic topics relating to law in some way, a few distinctive features help to demarcate work that is typically regarded as within law and economics. One distinguishing feature is that much of this work focuses on various areas of law that were not much studied by economists prior to the advent of law and economics; these areas include tort law, contract law, property law, and rules governing the litigation process. A second feature of work within law and economics is that it often (controversially) employs the normative criterion of “wealth maximization” (Posner 1979) rather than that of social welfare maximization—not, for the most part, on the view that society should pursue the maximization of wealth rather than social welfare, but instead because law and economics generally favors addressing distributional issues that bear on social welfare solely through the tax system (Shavell 1981). Finally, a third distinguishing feature of much work within law and economics is its sustained interest in explaining and predicting the content, rather than just the effects, of legal rules. While a large body of work in economics studies the effects of law (as noted above), outside of work associated with law and economics only political economy has generally given central emphasis to analyzing the content of law, and then only from a particular perspective.2

Given this rough sketch of “law and economics,” what then is “behavioral law and economics”? Behavioral law and economics involves both the development and the incorporation within law and economics of behavioral insights drawn from various fields of psychology. As has been widely recognized since the early work by Allais (1952) and Ellsberg (1961), some of the foundational assumptions of traditional economic analysis may reflect an unrealistic picture of human behavior. Not surprisingly, models based on these assumptions sometimes yield erroneous predictions. Behavioral law and economics attempts to improve the predictive power of law and economics by building in more realistic accounts of actors’ behavior.

The present paper describes some of the central attributes and applications of behavioral law and economics to date; it also outlines an emerging focus in behavioral law and economics on prospects for “debiasing” individuals through the structure of legal rules (Jolls and Sunstein 2006a). Through the vehicle of “debiasing through law,” behavioral law and economics may open up a new space within law and economics between, on the one hand, unremitting adherence to traditional economic assumptions and, on the other hand, broad structuring or restructuring of legal regimes on the assumption that people are inevitably and permanently bound to deviate from traditional economic assumptions.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 4.2 traces the development and refinement of one of the central insights of behavioral economics—that people frequently exhibit an endowment effect—both outside and within the field of behavioral law and economics. Section 4.3 moves to a general overview of the features of human decision making that have informed behavioral law and economics, emphasizing points of departure from work in other areas of behavioral economics. Section 4.4 describes a series of illustrative applications of behavioral law and economics analysis. Section 4.5 introduces the concept of debiasing through law, and Section 4.6 concludes.

Early on, law and economics had a central point of contact with behavioral economics. The point of contact was the foundational debate over the Coase Theorem and the “endowment effect”—the tendency of people to refuse to give up entitlements they hold even though they would not have bought those entitlements initially (Thaler 1980, pp. 43–47). This early point of contact between law and economics and behavioral economics helped to lay the ground for a rich literature down the road on the endowment effect in both behavioral economics and behavioral law and economics.

An unquestioned centerpiece of law and economics is the Coase Theorem (Coase 1960). This theorem posits that allocating legal rights to one party or another will not affect outcomes if transaction costs are sufficiently low; thus, for instance, whether the law gives a factory the right to emit pollution next to a laundry or, instead, says the laundry has a right to be free of pollution will not matter to the ultimate outcome (pollution or no pollution) as long as transaction costs are sufficiently low. The reason for this result is that, with low transaction costs, the parties should be expected to bargain to the efficient outcome under either legal regime. The Coase Theorem is central to law and economics because of (among other things) the theorem’s claim about the domain within which normative analysis of legal rules—whether rule A is preferable to rule B or the reverse—is actually relevant.

The Coase Theorem has also played a central, albeit a rather different, role in the field of behavioral economics. More than fifteen years ago, Kahneman et al. (1990) reported the results of a set of experiments designed to provide a careful empirical assessment of the Coase Theorem. In one round of experiments, each subject was given an assigned value for a “token” (the amount for which the subject could redeem the token for cash at the end of the experiment), and half of the subjects were awarded tokens. When subjects subsequently had the opportunity to trade tokens for money or (for those not awarded tokens) money for tokens, subjects behaved precisely in accordance with the Coase Theorem. Exactly half of the tokens changed hands, as theory would predict (given random assignment of the tokens in relation to the specified values). The initial allocation of tokens proved irrelevant. These findings are a striking vindication of the Coase Theorem.

Having thus established that transaction costs in the experimental setting were sufficiently low to vindicate the Coase Theorem, Kahneman et al. went on to study subjects’ behavior when the good to be traded was not tokens but, rather, Cornell University mugs that the subjects would retain after the experiment (rather than redeeming for an assigned amount of cash). In direct contravention of the Coase Theorem, the initial assignment of entitlements to the mug mattered dramatically; those initially given mugs rarely sold them, while those not initially given mugs seldom bought them. Following Thaler (1980, p. 44), Kahneman et al. referred to this effect as the “endowment effect”—the refusal to give up an entitlement one holds initially even though one would not have been willing to pay to acquire that entitlement had one not held it initially.3 In the presence of the endowment effect, the Coase Theorem’s prediction of equivalent outcomes regardless of the initial entitlement no longer holds. This conclusion has obvious importance for the design of legal rules.

A central task of law and economics is to assess the desirability of actual and proposed legal rules. The endowment effect both preserves a larger scope for such normative economic analysis—because the Coase Theorem and the associated claim of irrelevance of legal rules no longer hold—and profoundly unsettles the bases for such analysis.

The reason that the endowment effect so unsettles the bases for normative economic analysis of law is that in the presence of this effect the value attached to a legal entitlement will sometimes vary depending on the initial assignment of the entitlement. Normative analysis will then often become indeterminant, as multiple rules may maximize the desired objective (whether wealth or social welfare) depending on the starting allocation of entitlements (Kelman 1979, pp. 676–78). As Sunstein and Thaler (2003, p. 1190) recently observed, in the presence of the endowment effect a “cost–benefit study cannot be based on willingness to pay (WTP), because WTP will be a function of the default rule.” Thus, the cost–benefit study “must be a more open-ended (and inevitably somewhat subjective) assessment of the welfare consequences.”4 The conventional normative economic analysis feasible without the endowment effect often cannot survive in the presence of this effect.

One possible approach to normative analysis when the value of an entitlement varies depending on the initial assignment of the entitlement is to base legal policy choices not on the joint wealth or welfare of the parties directly in question—because the answer to the question of which rule maximizes their joint wealth or welfare may turn on the initial rule choice—but rather on the third-party effects of the competing rules. Thus, for instance, if it is unclear whether a particular workplace rule is or is not optimal for employers and employees (because employees will value the entitlement granted by the rule at more than its value with the rule in place but less than its value otherwise), but the rule will create important benefits for employees’ families, then perhaps the rule should be adopted.

An alternative approach to normative analysis with varying entitlement values depending on the initial assignment of the entitlement is to make a judgment about which preferences—the ones with legal rule A or the ones with legal rule B—deserve greater deference. Sunstein and Thaler (2003, pp. 1190–91) offer some support for this view in the context of default terms in employee savings plans. Referring to research showing that employees are much more likely to enroll in a savings plan if enrollment is the default term and employees must affirmatively opt out to be excluded than they are if non-enrollment is the default term and employees must take affirmative steps to enroll, Sunstein and Thaler make the normative argument that the enrollment outcome is “highly likely” to be better under automatic enrollment than under a default term of non-enrollment because it turns out that very few employees drop out if automatically enrolled. They readily acknowledge that “[s]ome readers might think that our reliance on [employees’] behavior as an indication of welfare is inconsistent” with the basic point about indeterminacy of preferences, “[b]ut in fact, there is no inconsistency” because “it is reasonable to think that if, on reflection, workers realized that they had been ‘tricked’ into saving too much, they might take the effort to opt out.” Sunstein and Thaler draw an analogy to rules calling for mandatory cooling-off periods before consumer purchases: “The premise of such rules is that people are more likely to make good choices when they have had time to think carefully and without a salesperson present.” In other words, according to Sunstein and Thaler, we have reason to think that the revealed preferences of the automatically enrolled employee, or the consumer at the end of a cooling-off period, are a more appropriate basis for normative judgment than the revealed preferences of the employee who does not choose to enroll under a default term of non-enrollment, or the consumer before the cooling-off period. We will see similar issues in the discussion of bounded willpower in Section 4.3.2 below.

Particularly in light of the central relevance of the endowment effect to normative economic analysis of law, it is appropriate to emphasize the important role of context in whether this effect occurs. An early literature in law and economics is responsible for helping to shape understandings of when the endowment effect will and will not occur.

Prior to the Cornell University “mugs experiments” described above, a series of law and economics articles had demonstrated a set of domains in which the Coase Theorem was in fact empirically robust. Hoffman and Spitzer’s (1982, 1986) experiments found that in both large and small groups the predictions of the theorem were vindicated. Likewise, Schwab (1988) showed that the ultimate allocation of entitlements did not turn on their initial allocation in the setting he studied.

All of these experiments, however, shared with the tokens experiment discussed above the feature that subjects’ value of each possible outcome was directly specified in dollar terms by the experimenter. Thus, the law and economics work from the 1980s showed that if people are told specifically what each outcome is worth to them, they will generally find their way to a value-maximizing outcome, so long as transaction costs are sufficiently low. However, the later “mugs experiments” demonstrated that this result tends to collapse when actors are not instructed as to the value of outcomes to them. Viewed in light of the later work, the law and economics work from the 1980s is best understood as showing some of the important limits on when the endowment effect will be observed and, more generally, the central role of context in influencing the occurrence or nonoccurrence of this effect. The work by Plott and Zeiler (2005) provides an important recent lens on the role of context in determining the existence and degree of the endowment effect.

Within behavioral law and economics, recent research has refined the basic point about the importance of context. Korobkin (1998), for instance, raised the important question of whether the endowment effect would obtain in the allocation to either prospective sellers or prospective buyers of contract law default rights, such as the right of sellers to withhold goods or services after unanticipated natural disasters or other similar events versus the right of buyers to demand goods or services in those circumstances. (For instance, if a theater owner has promised to allow its theater to be used by another party on a specific date, but the theater then burns down before that date, does the theater owner have the right not to provide the theater, or does the other party have the right to collect damages for the harm it suffered because the theater proved unavailable?) Such contact law entitlements do not attach—and indeed are irrelevant—until and unless a contract is ultimately agreed to, and thus Korobkin noted that it was unclear whether the initial allocation of the entitlements through contract law default rules would create the sort of sense of ownership or possession that in turn would generate an endowment effect.

Korobkin’s experiments support the operation of the endowment effect in this context. He finds that if contract law allocates an entitlement to party A unless party A agrees to waive it, then a contract between that party and party B is more likely to award party A that entitlement than if contract law initially allocates the entitlement to party B—even with seemingly low transaction costs. Thus, Korobkin concludes, the endowment effect, and not the Coase Theorem, provides the best account of the effects of contract law default rights. The deepening of knowledge about when the endowment effect does and does not occur—across contract settings and elsewhere—will help refine our understanding of the scope of this effect and, as a direct consequence, the validity of and limits on conventional normative economic analysis of law.

Although the endowment effect has played a central role in behavioral law and economics, other features of behavioral economics are important as well. Following Thaler (1996), it is useful for purposes of behavioral law and economics analysis to view human actors as departing from traditional economic assumptions in three distinct ways: human actors exhibit bounded rationality, bounded willpower, and bounded self-interest. All three concepts are defined in the brief discussion below. As described below, bounded rationality consists in part of “judgment errors,” and along with the usual types of such errors discussed in the existing literature in behavioral economics, behavioral law and economics has recently emphasized a separate form of judgment error—implicit bias in how members of racial and other groups are perceived by individuals who consciously disavow any sort of prejudiced attitude; this form of judgment error provides the starting point for the discussion below.

Departures from traditional economic assumptions of unbounded rationality may be divided into two main categories, judgment errors and departures from expected utility theory.

Across a wide range of contexts, actual judgments show systematic differences from unbiased forecasts. Within this category of judgment errors, behavioral law and economics has recently emphasized errors in the form of implicit bias in people’s perceptions of racial and other group members.

Implicit Racial and Other Group-Based Bias. Perhaps the most elementary definition of the word “bias” is that a person believes, either consciously or implicitly, that members of a racial or other group are somehow less worthy than other individuals. An enormous literature in modern social psychology explores the cognitive, motivational, and other aspects of implicit, or unconscious, forms of racial or other group-based bias. This literature, however, has not featured significantly in most fields of behavioral economics. But a clear contrast is behavioral law and economics, which has recently given significant emphasis to the possibility and effects of implicit racial or other group-based bias.

The behavioral law and economics literature in this area has worked against the backdrop of a heavily Beckerian approach to discrimination. Seminal law and economics works on discrimination envision such behavior as in significant part a rational response to discriminatory “tastes” that disfavor association with particular group members (e.g., Posner 1989). The idea of implicit bias, by contrast, suggests that discriminatory behavior often stems not from taste-based preferences that individuals are consciously acting to satisfy, but instead from implicit attitudes afflicting individuals who seriously and sincerely disclaim all forms of prejudice, and who would regard their implicitly biased judgments as “errors.” A number of recent works in behavioral law and economics have begun to explore the implications for the analysis of discrimination law of various types of implicit bias (e.g., Gulati and Yelnosky forthcoming; Jolls and Sunstein 2006b).

While social psychologists have identified diverse means of assessing and measuring implicit bias against members of racial and other groups (e.g., Gaertner and McLaughlin 1983; Greenwald et al. 1998), a particular measure, known as the Implicit Association Test (IAT), has had particular influence. In the IAT, individuals are asked to categorize words or pictures into four groups, two of which are racial or other groups (such as “black” and “white”), and the other two of which are the categories “pleasant” and “unpleasant.” Groups are paired, so that respondents are instructed to press one key on the computer for either “black” or “unpleasant” and a different key for either “white” or “pleasant” (a stereotype-consistent pairing); or are instructed instead to press one key on the computer for either “black” or “pleasant” and a different key for either “white” or “unpleasant” (a stereotype-inconsistent pairing). Implicit bias is defined as faster categorization when the “black” and “unpleasant” categories are paired than when the “black” and “pleasant” categories are paired. The IAT reveals significant evidence of implicit bias, including among those who assiduously deny any prejudice (Greenwald et al. 1998; Nosek et al. 2002).

An important question raised by the results on the IAT is whether implicit bias as measured by the test is correlated with individuals’ actual behavior toward members of other groups. Several studies, including McConnell and Leibold (2001) and Dovidio et al. (2002), have found that scores on the IAT and similar tests show correlations with third parties’ ratings of the degree of general friendliness shown by individuals toward members of other groups. Other connections between IAT scores and actual behavior remain an active area of research.

Although implicit racial or other group-based bias is not conventionally grouped with other forms of bounded rationality within behavioral economics, the fit may be more natural than has typically been supposed. Such implicit bias may often result from the way in which the characteristic of race or other group membership operates as a sort of “heuristic”—a form of mental shortcut. (The concept of a heuristic is discussed more fully just below.) Indeed, recent psychology research emphasizes that heuristics often work through a process of “attribute substitution,” in which people answer a hard question by substituting an easier one (Kahneman and Frederick 2002). For instance, people might resolve a question of probability not by investigating statistics, but by asking whether a relevant incident comes easily to mind (Tversky and Kahneman 1973). The same process can operate to produce implicit bias against racial or other groups. Section 4.5.1, below, describes an example of how implicit bias has been analyzed within behavioral law and economics.

The “Heuristics and Biases” Literature. Judgment errors may arise not only from implicit bias against racial or other group members, but also from other biases studied within the so-called “heuristics and biases” literature within behavioral economics. Three types of judgment errors from this literature have received particularly sustained attention within behavioral law and economics.

One such judgment error is optimism bias, in which individuals believe that their own probability of facing a bad outcome is lower than it actually is. As a familiar illustration, most people think that their chances of having an auto accident are significantly lower than the average person’s chances of experiencing this event (e.g., DeJoy 1989), although of course these beliefs cannot all be correct; if everyone were below “average,” then the average would be lower.5 There is also evidence that people underestimate their absolute as well as relative (to other individuals) probability of negative events such as auto accidents (Arnould and Grabowski 1981, pp. 34–35; Camerer and Kunreuther 1989, p. 566). Optimism bias is probably highly adaptive as a general matter; by thinking that things will turn out well, people may often increase the chance that they will turn out well. Section 4.4.1, below, describes an application of optimism bias in the behavioral law and economics literature.

A second judgment error prominent in behavioral law and economics is self-serving bias. Whenever there is room for disagreement about a matter to be decided by two or more parties—and of course there often is in litigation as well as elsewhere—individuals will tend to interpret information in a direction that serves their own interests. In a compelling field study, Babcock et al. (1996) find that union and school board presidents asked to identify “comparable” school districts for purposes of labor negotiations identified different lists of districts depending on their respective self-interests. While the average teacher salary in districts viewed as comparable by union presidents was $27,633, the same average was $26,922 in districts viewed as comparable by school board presidents. As Babcock et al. observe, this difference was more than large enough to produce teacher strikes based on the size of past salary disagreements leading to strikes. Section 4.4.2, below, discusses an application of self-serving bias in the behavioral law and economics literature.

A third judgment error extensively discussed in behavioral law and economics is the hindsight bias, in which decision makers attach excessively high probabilities to events simply because they ended up occurring. In one striking study, neuro-psychologists were presented with a list of patient symptoms and then asked to assess the probability that the patient had each of three conditions (alcohol withdrawal, Alzheimer’s disease, and brain damage secondary to alcohol abuse). While the mean probabilities for physicians who were not informed of the patient’s actual condition were 37%, 26%, and 37%, respectively, for the three conditions, physicians who were informed of the patient’s actual condition routinely said they would have attached much higher probabilities to that condition (Arkes et al. 1988). Even when, as in the study, people are specifically instructed to give the probabilities they would have assigned had they been the one making the initial diagnosis, people seem to have difficulty putting aside events they know to have occurred. As highlighted in Section 4.4.5, below, the hindsight bias has clear relevance to the legal system because that system is pervasively in the business of adjudicating likelihoods and foreseeability after an accident or other event has occurred.

Boundedly rational individuals not only make judgment errors but also deviate from the precepts of expected utility theory. While this theory is a foundational aspect of traditional economic analysis, Kahneman and Tversky’s (1979) “prospect theory” offers a leading alternative to expected utility theory. Within behavioral law and economics, the feature of prospect theory that emphasizes the distinction between gains and losses relative to an endowment point has received by far the most attention; the relevant work on the endowment effect was discussed in some detail in Section 4.2 above.

We often observe individuals choosing to spend rather than save, consume desserts over salads, and go to the movies instead of the gym despite all of their best intentions (Schelling 1984; Laibson 1997). Why do people fail to follow through on the plans they make? Behavioral economics has emphasized the concept of bounded willpower, which has a long pedigree in economics (Strotz 1955/56). This concept has featured in behavioral law and economics as well, as illustrated in Section 4.4.4, below.

Much work in law and economics is normatively oriented, and this feature of the work brings to the fore a set of normative questions about bounded willpower—much in the way that normative questions have been prominent in law and economics discussions of the endowment effect (Section 4.2.2, above). With respect to bounded willpower, the central normative question concerns how to view a decision to spend rather than save, to consume desserts rather than salads, or to go to the gym rather than the movies. Why should (if they should) the preferences of the self who wishes to save, eat salad, or go to the gym rather than the self who wishes to spend, eat dessert, or watch movies be used as the benchmark in performing normative analysis?

One possible answer, partially reminiscent of a strand of the endowment effect discussion above, is that saving, eating salad, or going to the gym creates desirable third-party effects that are absent with spending, eating dessert, or watching movies. Another possible answer, also with an analogue in the earlier discussion, is that the preferences of the self who wishes to save, eat salad, or go to the gym reflect a considered judgment about the matter in question—the rightness of which, however, it is not possible always to keep before one’s mind (Elster 1979, p. 52). Of course, each of these two types of judgments about the relative merits of different preferences may be contentious in at least some settings.

In principle, traditional economic analysis is capacious with respect to the range of admissible preferences. Preferences that give significant weight to fairness, for instance, can be included in the analysis (Kaplow and Shavell 2002, pp. 431–34). In practice, however, much of traditional law and economics posits a relatively narrow set of ends that individuals are imagined to pursue.

Contrary to this conventional approach, bounded self-interest within behavioral economics emphasizes that many people care about both giving and receiving fair treatment in a range of settings (Rabin 1993). As Thaler and Dawes (1992, pp. 19–20) observe:

In the rural areas around Ithaca it is common for farmers to put some fresh produce on a table by the road. There is a cash box on the table, and customers are expected to put money in the box in return for the vegetables they take. The box has just a small slit, so money can only be put in, not taken out. Also, the box is attached to the table, so no one can (easily) make off with the money. We think that the farmers who use this system have just about the right model of human nature. They feel that enough people will volunteer to pay for the fresh corn to make it worthwhile to put it out there.

Of course, a central question raised by bounded self-interest is what counts as “fair” treatment. Behavioral economics suggests that people will judge outcomes as unfair if they depart substantially from the terms of a “reference transaction”—a transaction that defines the benchmark for the parties’ interactions (Kahneman et al. 1986a). In the basic version of the well-known ultimatum game, for instance, where parties divide a sum of money with no reason to think one party is particularly more deserving than the other, the “reference transaction” is something like an equal split; substantial departures from this benchmark are viewed as unfair and, accordingly, are punished by parties who receive offers of such treatment (Güth et al. 1982; Kahneman et al. 1986b). Section 4.5, below, illustrates how this conception of bounded self-interest has been applied within behavioral law and economics.

The present section offers a set of illustrative applications of behavioral law and economics. The discussion seeks to illustrate what has become essentially “normal science” within the literature in behavioral law and economics to date: identification of a departure from unbounded rationality, willpower or self-interest, followed by either an account of existing law or a proposed legal reform that takes as a fixed point the identified departure from unbounded rationality, willpower or self-interest. Section 4.5 shifts the focus to a new approach within behavioral law and economics, one that emphasizes the potential for responding to some bounds on human behavior not by taking people’s natural tendencies as given and shaping law around them but, instead, by attempting to reduce or eliminate such human tendencies through the legal structure—the approach of “debiasing through law” (Jolls and Sunstein 2006a).

Recent surveys on behavioral law and economics by Guthrie (2003), Korobkin (2003), and Rachlinski (2003) have examined existing legally oriented work on bounded rationality, devoting extensive attention to both judgment errors and departures from expected utility theory.6 The present section, by contrast, focuses on a limited number of applications of bounded rationality, willpower and self-interest, attempting to give a fuller picture of some of the relevant work in these areas.

As noted in Section 4.1, above, one distinctive feature of law and economics is its frequent focus on wealth maximization—giving legal entitlements to those most willing to pay for them, without regard for distributional considerations—rather than social welfare maximization as the criterion for normative analysis. Many law and economics scholars object to “distributive legal rules”—non-wealth-maximizing legal rules chosen for their distributive consequences—because they believe that distributional issues are best left solely to the tax system (Kaplow and Shavell 1994).

A leading law and economics argument in favor of addressing distributional issues through the tax system rather than through nontax legal rules is the argument that any desired distributional consequence can be achieved at lower cost through the tax system than through distributive legal rules. Of course, pursuit of distributional objectives through the tax system is not costless; higher taxes on the wealthy will tend to distort work incentives. But under traditional economic assumptions precisely the same is true of distributive legal rules: “[U]sing legal rules to redistribute income distorts work incentives fully as much as the income tax system—because the distortion is caused by the redistribution itself . . .” (Kaplow and Shavell 1994, pp. 667–68). Thus, for example, under traditional economic analysis a 30% marginal tax rate, together with a non-wealth-maximizing legal rule that transfers an average of 1% of high earners’ income to the poor, creates the same distortion in work incentives as a 31% marginal tax rate coupled with a wealth-maximizing legal rule. However, the former regime also entails costs due to the non-wealth-maximizing legal rule. (For instance, under a distributive legal rule governing accidents, potential defendants may be excessively cautious and thus may be discouraged from engaging in socially valuable activities.) Thus, whatever the desired distributive consequences, under traditional economic analysis they can always be achieved at lower cost by choosing the wealth-maximizing legal rule and adjusting distributive effects through the tax system than by choosing a non-wealth-maximizing rule because of its distributive properties (Shavell 1981).

A basic premise about human behavior underlies this analysis. Work incentives are assumed to be distorted by the same amount as a result of a probabilistic, nontax mode of redistribution, such as the law governing accidents, as they are as a result of a tax. Thus, for example, if high-income individuals face a 0.02 probability of incurring tort liability for an accident, then a distributive legal rule that imposes $500,000 extra in damages (beyond what a wealth-maximizing rule would call for) would distort work incentives by the same amount as a tax of $10,000, assuming risk-neutrality.8

Why would distributive tort liability and taxes have the same effects on work incentives? “[W]hen an individual . . . contemplates earning additional income by working harder, his total marginal expected payments [out of that income] equal the sum of his marginal tax payment and the expected marginal cost on account of accidents” (Kaplow and Shavell 1994, p. 671).

The expected costs of the two forms of redistribution are the same, and thus behavior is affected in the same way. At least that is the assumption that traditional economic analysis makes.

Is this assumption valid? From a behavioral economics perspective, it is not clear that an individual would typically experience the same disincentive to work as a result of a more generous (to victims) tort-law regime as would be experienced as a result of a higher level of taxation.9 The discussion here will highlight one important reason, related to the phenomenon of optimism bias noted in Section 4.3, above, that behavioral law and economics suggests work incentives may be distorted less by distributive tort liability—which operates probabilistically rather than deterministically—than by taxes. Other reasons for different effects of the two regimes, based on different contextual factors across the regimes, are discussed in Jolls (1998).

As just noted, a salient feature of distributive tort liability is the uncertainty of its application to any given actor. The effect of such liability “tends to be limited to those few who become parties to lawsuits” (Kaplow and Shavell 1994, p. 675). While one knows that one will have to pay taxes every year, one knows that one is quite likely not to become involved in an accident. To be sure, the possibility of uncertain or randomized taxation has received some discussion in the public finance literature. Even supporters of this approach, however, suggest that it is unrealistic from a practical perspective (Stiglitz 1987, pp. 1012–13).

Bounded rationality in the form of optimism bias—the tendency to think negative events are less likely to happen to oneself than they actually are—suggests that uncertain events are often processed systematically differently from certain events. Section 4.3.1.1 above referred to the general body of evidence suggesting the prevalence of optimism bias; there are also empirical studies suggesting that people offer unrealistically optimistic assessments in areas directly related to the effects of distributive tort liability. For instance, most people think that they are less likely than the average person to be sued (Weinstein 1980, p. 810). Likewise, people think that they are less likely than the average person to cause an auto accident (Svenson et al. 1985; DeJoy 1989). They also think that their own probability of being caught and penalized for drunk driving is lower than the average driver’s probability of being apprehended for such behavior (Guppy 1993).

What does optimism bias with respect to the probability of the negative event of tort liability imply for the distortionary effects of distributive tort liability as opposed to taxes? People will tend to underestimate the probability that they will be hit with liability under distributive tort liability; therefore, their perceived cost of the rule will be lower. As a result, their work incentives will tend to suffer a lesser degree of distortion than under a tax yielding the same amount of revenue for the government. For instance, in the numerical example from above, risk-neutral individuals may not attach an expected cost of $10,000 to a 0.02 (objective) probability of having to pay $500,000 extra in damages under distributive tort liability; they may tend to underestimate the probability that they will incur liability—and thus they may tend to underestimate the expected cost of liability—as a result of optimism bias.10

Of course, optimism bias is not the only phenomenon that affects how people assess the likelihood of uncertain events. In some cases people may tend to overestimate rather than underestimate the probability of a negative event because the risk in question is highly salient or otherwise available to them—for instance, contamination from a hazardous waste dump (Kuran and Sunstein 1999, pp. 691–97). However, the overestimation phenomenon seems relatively unlikely to affect the assessment of distributive tort liability, at least insofar as individuals rather than firms are concerned. Consider, for instance, the quintessential event that can expose an individual to tort liability: the auto accident. As noted above, people appear to underestimate the probability that they will be involved in an auto accident (relative to the actual probability); this presumably results from a combination of underestimation of the general probability of an accident (Lichtenstein et al. 1978, p. 564) and further underestimation of people’s own probability relative to the average person’s (Svenson et al. 1985; DeJoy 1989). The situation would probably be different, of course, for an event such as contamination from a hazardous waste dump, the probability of which might be overestimated due to its availability; but highly available events tend to involve firm, not individual, liability. It is difficult to come up with examples of events giving rise to individual liability the probability of which is likely to be overestimated rather than (as suggested above) underestimated. And with underestimation of the probability of liability, work incentives will typically be distorted less by distributive legal rules than by taxes.

Section 4.1, above, noted that an important aspect of work in law and economics is analysis of various areas of law that were not previously studied by economists. One such area concerns the rules governing the litigation process. When someone believes that a law has been violated, how does the legal system go about deciding the legitimacy of that claim? The U.S. system relies centrally upon an adversary approach, under which competing sides are represented by legal counsel who argue in favor of their respective positions.

Of course, maximally effective advocacy for a position often requires one to obtain information under the control of one’s opponent, and thus the U.S. legal system contains a set of rules governing when and how one side in a legal dispute may obtain (“discover”) information from the other side. Since 1993 these rules have required opposing parties to disclose significant information even without a request by the other party (Issacharoff and Loewenstein 1995). Under conventional economic analysis this approach should tend to increase the convergence of parties’ expectations and, thus, the rate at which they settle disputes out of court (e.g., Shavell 2004, p. 427).

The phenomenon of self-serving bias described in Section 4.3.1.1, above, however, suggests that individuals often interpret information differently depending on the direction of their own self-interest. Experimental work by Loewenstein et al. (1993), Babcock et al. (1995), and Loewenstein and Moore (2004) has examined self-serving bias in the specific context of litigation. In the first paper in the series, Loewenstein et al. found that parties assigned to the role of plaintiff or defendant interpreted the very same facts differently depending on their assigned role; subjects assigned to the plaintiff role offered higher estimates of the likely outcome at trial than subjects assigned to the defendant role even though they both received identical information about the case. Moreover, the authors found that subjects who exhibited the highest levels of self-serving bias were also least likely to succeed in negotiating out-of-court settlements. This work provided opening evidence of the role of self-serving bias in shaping the effect of information disclosure on the rate at which legal disputes are settled.

The initial study just described could not rule out the possibility that the relationship between the degree of self-serving bias and the frequency of settlement was non-causal, for it is possible that an unmeasured factor influenced both the degree of self-serving bias and the frequency of settlement. In a follow-up study, however, Babcock et al. (1995) provided strong evidence that the relationship was in fact causal. They found that parties who were not informed of their roles until after reading case materials and offering their estimates of the likely outcome at trial both failed to exhibit statistically significant degrees of self-serving bias and settled at significantly greater rates than parties who were informed of their roles before reading the case materials. The timing of exposure to the case materials matters because “[s]elf-serving interpretations are likely to occur at the point when information about roles is assimilated,” for the simple reason that it “is easier to process information in a biased way than it is to change an unbiased estimate once it has been made” (Babcock et al. 1995, p. 1339). The recent study by Loewenstein and Moore (2004) underlines the fact that self-serving bias will operate when there is some degree of ambiguity about the proper or best interpretation of a set of information, as will frequently be the case in litigation.

The prospect that litigants will interpret at least some information in a self-serving fashion means that the exchange of information in litigation may cause a divergence rather than convergence of parties’ expectations. Relying in part on this argument, Issacharoff and Loewenstein (1995) suggest that mandatory disclosure rules in litigation may be undesirable. As they describe, self-serving bias undermines the conventional wisdom that “a full exchange of the information in the possession of the parties is likely to facilitate settlement by enabling each party to form a more accurate, and generally therefore a more convergent, estimate of the likely outcome of the case” (Posner 1992, p. 557; quoted in Issacharoff and Loewenstein 1995, p. 773).

Consistent with Issacharoff and Loewenstein’s argument, a set of amendments in 2000 significantly cut back—although they did not completely eliminate—the mandatory disclosure rules noted above (192 Federal Rules Decisions 340, p. 385).

The third distinctive feature of law and economics discussed in Section 4.1, above, concerned the field’s interest in explaining and predicting the content of law—what the law allows and what it prohibits. Law and economics has emphasized the idea that laws may be efficient solutions to the problems of organizing society; it has also emphasized—as has the field of political economy—that laws may come about because of the rent-seeking activities of politically powerful actors (Stigler 1971).

Behavioral law and economics has extended this conventional account of the content of legal rules in two important ways. The first, which is the focus of the discussion in this subsection, is that in many cases incorporation of insights about bounded rationality, willpower and self-interest is needed for a satisfactory understanding of law’s efficiency properties. A law may be efficient in part because of the way in which it accounts for one of the three bounds on human behavior, as the discussion below illustrates. The second extension of the conventional law and economics account of the content of law is the expansion of behavioral law and economics beyond the two familiar categories from the traditional account—the category of law-as-efficiency-enhancing and the category of law-as-the-product-of-conventional-rent-seeking. Section 4.4.5 discusses and illustrates this second extension developed by behavioral law and economics.

A prominent behavioral law and economics work seeking to understand and explain the efficiency of the content of law is Rachlinski (1998). Rachlinski examines a number of areas of law, including corporate law. A central rule of U.S. corporate law is the “business judgment” rule, according to which corporate officers and directors who are informed about a corporation’s activities and who approve or acquiesce in these activities have generally fulfilled their duties to the corporation as long as they have a rational belief that such activities are in the interests of the corporation. This highly deferential standard of liability makes it difficult to find legal fault for the decisions of corporate officers and directors.

Rachlinski suggests that the business judgment rule may be corporate law’s sensible response to the problem of hindsight bias. As described above, hindsight bias suggests that the sorts of decisions routinely made by the legal system, adjudicating likelihoods and foreseeability after a negative event has materialized, will often be biased toward excessively high estimates—and thus in favor of holding actors responsible—simply because the negative event materialized. But under the business judgment rule, officers and directors will not be held liable for decisions that turn out badly—“even if these decisions seem negligent in hindsight” (Rachlinski 1998, p. 620). Hindsight bias suggests that things will often seem negligent in hindsight, once a negative outcome has materialized and is known, so the business judgment rule insulates officers and directors from the risk of such hindsight-influenced liability determinations. In the absence of the business judgment rule, Rachlinski argues, officers and directors would fail to make the risk-neutral business decisions desired by investors who can limit their overall investment risk through diversification; “[e]nsuring that managers effectively represent this concern and do not avoid business decisions that have a high expected payoff but also carry a high degree of risk is a central problem of corporate governance” (Rachlinski 1998, p. 622). In this respect, hindsight bias can help to explain the efficiency of the content of law governing corporate officers and directors.

The behavioral law and economics applications discussed thus far have involved bounded rationality, but other applications have drawn on the other two bounds on human behavior. This subsection describes an application of the concept of bounded willpower within behavioral law and economics.

As discussed above, an individual with bounded willpower will often have difficulty sticking to even the best-laid plans. With respect to decisions about consumption versus saving, for instance, individuals who earnestly plan to save a substantial amount of next year’s salary for retirement may tend, once next year arrives, to save far less than planned. If the failure to stick to the initial plan is understood in advance, then individuals may seek to precommit themselves to their initial plan. An obvious potential means of achieving such precommitment is a contract between the individual suffering from bounded willpower and a bank or other savings institution; but the efficacy of this approach from the standpoint of the individual at the time of contemplating such a contract depends critically on whether contracts are, or can be made, nonrenegotiable. Down the road it will always be in the parties’ mutual interest to renegotiate the initial contract, for at later points the individual will be better off if the individual can consume more and save less than the amount the original contract called for, and thus at that point there is a surplus from renegotiation to be divided between the parties. Only if renegotiation is impossible can the parties avoid the effects of bounded willpower and achieve commitment to the initial plan.

The obvious question is then whether contract law allows nonrenegotiable contracts. Certainly the default rule of contract law is that renegotiated agreements are enforceable. The primary exception to enforcement of such agreements concerns renegotiated agreements coerced by one party’s threat to breach the original contract if renegotiation does not occur.12 But in the model discussed here, renegotiation is truly welfare-enhancing—at the time at which it occurs—for both parties relative to the original contract, so the coercion concern does not apply, and thus the default rule would allow enforcement of the renegotiated agreement.

Does contract law allow the parties to supplement the default rules governing renegotiation with additional terms of their own? Perhaps surprisingly, the answer to this question is generally “no.” Justice Cardozo’s 1919 opinion in Beatty v. Guggenheim Exploration Co. provides a classic example of the rule and its underlying rationale:

Those who make a contract, may unmake it. The clause which forbids a change, may be changed like any other. . . . ‘Every such agreement is ended by the new one which contradicts it.’ . . . What is excluded by one act, is restored by another. You may put it out by the door, it is back through the window. Whenever two men contract, no limitation self-imposed can destroy their power to contract again.

(225 N.Y. 380, pp. 387–88 (citations omitted))

While existing contract law thus prohibits enforcement of contractual agreements not to renegotiate, a natural question is whether a contrary rule would be of any effect. Any clause limiting or prohibiting renegotiation will be effective only if some party to the contract has an incentive to enforce the clause. Jolls (1997) provides discussion of circumstances in which this will be the case. Consistent with the discussion here, the law has started to move away from the formalistic principle described above and in some instances now permits parties by contract to remove their future power to renegotiate their original contract orally (although written renegotiated agreements are still generally enforceable) (Uniform Commercial Code sec. 2-209).

A final illustration of behavioral law and economics reveals the way that work in this area has expanded upon the traditional law and economics notion that law’s content reflects either efficiency or conventional rent-seeking. The notion that laws emerge from these two considerations would probably strike most citizens as odd. Instead, most members of society—which is to say most of the people who are entitled to elect legislators—believe that the primary purpose of the law is to codify “right” and “wrong.” Can this idea be formalized, drawing in part on the notion of bounded self-interest from Section 4.3.3 above?

Consider the case of consumer protection law, which imposes bans on certain market transactions including (in many jurisdictions) “usurious” lending and some forms of price gouging (see, e.g., Uniform Consumer Credit Code sec. 2.201). What accounts for these laws, which impose constraints on gain-producing transactions for ordinary commodities such as television sets and lumber? The bans seem difficult to justify on efficiency grounds; rules prohibiting mutually beneficial exchanges without obvious externalities are not generally thought to have a large claim to efficiency. The laws also do not generally seem well explained in terms of conventional rent seeking by a politically powerful faction.14

By contrast, laws banning usurious lending and price gouging when such activities are prevalent are a straightforward prediction of the theory of bounded self-interest described above. (The analysis here assumes that self-interested legislators are responsive to citizens’ or other actors’ fairness-based demands for the content of law.15) In the case of such bans, the transaction in question is a significant departure from the usual terms of trade in the market for the good in question—that is, a significant departure from the “reference transaction.” The account above of bounded self-interest suggests that if trades are occurring frequently in a given jurisdiction at terms far from those of the reference transaction, there will be strong pressure for a law banning such trades. Note that the prediction is not that all high prices (ones that make it difficult or impossible for some people to afford things they might want) will be banned; the prediction is that transactions at terms far from the terms on which those transactions generally occur in the marketplace will be banned.

Consider this example:

A store has been sold out of the popular Cabbage Patch dolls for a month. A week before Christmas a single doll is discovered in a store room. The managers know that many customers would like to buy the doll. They announce over the store’s public address system that the doll will be sold by auction to the customer who offers to pay the most.

Kahneman et al. (1986a, p. 735)

Nearly three-quarters of the respondents judged this action to be either somewhat unfair or very unfair, though, of course, an economic analysis would judge the auction the most efficient method of assuring that the doll goes to the person who values it most. Although the auction is efficient, it represents a departure from the “reference transaction,” under which the doll is sold at its usual price.

As in the doll example, if money is loaned to individuals at a rate of interest significantly greater than the rate at which similarly sized loans are made to other customers, then the lender’s behavior may be viewed as unfair. Likewise, because lumber generally tends to sell for a particular price, sales at far higher prices in the wake of (say) a hurricane, which drives demand sky high, are thought unfair. How then should popular items be rationed? Subjects in one study asked whether a football team should allocate its few remaining tickets to a key game through an auction thought that this approach would be unfair, while allocation based on who waited in line longest was the preferred solution (Kahneman et al. 1986b, pp. S287–88). Of course, waiting in line for scarce goods is precisely what happens with laws against price gouging. Thus, pervasive fairness norms appear to shape attitudes (and hence possibly law) on both usury and price gouging. While “[c]onventional economic analyses assume as a matter of course that excess demand for a good creates an opportunity for suppliers to raise prices” and that “[t]he profit-seeking adjustments that clear the market are . . . as natural as water finding its level—and as ethically neutral,” “[t]he lay public does not share this indifference” (Kahneman et al. 1986a, p. 735).

Note that the behavioral law and economics analysis does not imply that these views of fairness are necessarily rational or compelling. Many of those who think “usurious” lenders are “unfair” might not have thought through the implications of their views (for example, that paying an outrageous price for a loan may be better than paying an infinite price, or that a loan to a riskier borrower is a product different in kind from a loan to a safer borrower). Still, if such views are widespread, they may underlie certain patterns in the content of law, such as the legal restrictions on usury and price gouging. The claim here is a positive one about the content of the law we observe, not a prescriptive or normative one about the shape practices or rules should take. As a positive matter, behavioral law and economics predicts that if trades are occurring with some frequency on terms far from those of the reference transaction, then legal rules will often ban trades on such terms.

Of course, further inquiry would be needed to offer a definitive explanation for the full pattern of usury and price gouging laws we observe. Usury seems to be broadly prohibited, so one is not faced with the question of why we observe bans in some states but not others. The same cannot be said of price gouging, which is prohibited only in certain states. Price gouging appears to be prohibited primarily by states that have recently experienced (or whose neighbors have recently experienced) natural disasters; but more in-depth research would be required to determine if this pattern comprehensively bears out.

The applications described in Section 4.4 illustrate the usual approach in behavioral law and economics work to date: the analysis identifies a departure from unbounded rationality, willpower or self-interest and then offers either a proposed legal reform or an account of existing law that takes as a fixed point the identified departure from unbounded rationality, willpower or self-interest. This approach might be said to focus on designing legal rules and institutions so that legal outcomes do not fall prey to problems of bounded rationality, willpower or self-interest—a strategy of insulation of those outcomes from such bounds on human behavior.

A quite different possibility, focused most heavily on the case of judgment errors by boundedly rational actors, is that legal policy may respond best to such errors not by structuring rules and institutions to protect legal outcomes from the effects of the errors (which themselves are taken as a given), but instead by operating directly on the errors and attempting to help people either to reduce or to eliminate them. Legal policy in this category may be termed “debiasing through law”; the law is used to reduce the degree of biased behavior actors exhibit (Jolls and Sunstein 2006a). The primary emphasis is on judgment errors rather than either other aspects of bounded rationality or bounded willpower or self-interest, for the simple reason that those alternative forms of human behavior cannot uncontroversially be viewed as “biases” in need of debiasing. (Recall, for instance, the normative complexities discussed above in connection with both the endowment effect and bounded willpower. And clearly it would not generally be desirable to “debias” boundedly self-interested actors.) As described below, the basic promise of strategies for debiasing through law is that these strategies will often provide a middle ground between unyielding adherence to the assumptions of traditional economics, on the one hand, and the usual behavioral law and economics approach of accepting departures from those assumptions as a given, on the other.

The idea of debiasing through law draws on a substantial existing psychology literature on the debiasing of individuals after a demonstration of the existence of a given judgment error (e.g., Fischhoff 1982; Weinstein and Klein 2002). Those who have investigated debiasing in experimental settings, however, have generally not explored the possibility of achieving debiasing through law. A few behavioral law and economics papers have examined the possibility of debiasing through the procedural rules governing adjudication by judges or juries; a well-known example builds on the studies described in Section 4.4.2, above, of self-serving bias in litigation and shows how requiring litigants to consider reasons the adjudicator might rule against them eliminates their self-serving bias (Babcock et al. 1997). However, the potential promise of debiasing through law is far broader, for it is not only the procedures by which law is applied in adjudicative settings but the actual substance of law that may be employed to achieve debiasing.

Consider an example of debiasing through law developed by Jolls (forthcoming), drawing on the work on implicit racial or other group-based bias described in Section 4.3.1.1, above. Might substantive rules governing employment discrimination play a role in debiasing individuals who exhibit such bias? Empirical studies suggest that implicit racial or other group-based bias is profoundly influenced by environmental stimuli. Individuals who view pictures of Tiger Woods and Timothy McVeigh before submitting to testing of implicit racial bias, for example, exhibit substantially less bias than individuals not exposed to the pictures of Woods and McVeigh (Dasgupta and Greenwald 2001). This study and, more broadly, the large social science literature on debiasing in response to implicit racial or other group-based bias (e.g., Macrae et al. 1995; Dasgupta and Asgari 2004) have an intriguing practical counterpart in the ongoing controversies at many universities and the U.S. Capitol over the frequent pattern of largely or exclusively white, male portraits adorning classrooms and ceremonial spaces (Gewertz 2003; Stolberg 2003). In the employment context, it may not be irrelevant to the degree of implicit racial or other group-based bias found in employment decision makers whether, for instance, the walls of the workplace feature sexually explicit depictions of women—the source of frequent sexual harassment lawsuits—or instead feature more positive, affirming images of women. Employment discrimination law’s policing of what can and cannot be featured in the workplace environment, described in detail in Jolls (forthcoming), is thus an illustration of debiasing through substantive law.

It is important to emphasize the limits of the domain of this analysis of employment discrimination law as a mechanism for achieving “debiasing” in the sense in which the term is used here. In some cases racial or other group-based bias may reflect genuine tastes rather than, as discussed above, a divergence of implicit attitudes and behavior from non-discriminatory tastes. Of course, the features of employment discrimination law just referenced might still be desirable, and would certainly remain applicable, in the case of consciously discriminatory tastes, but they would no longer illustrate a form of debiasing through law in the sense used here because no form of judgment error would be under correction in the first place.16

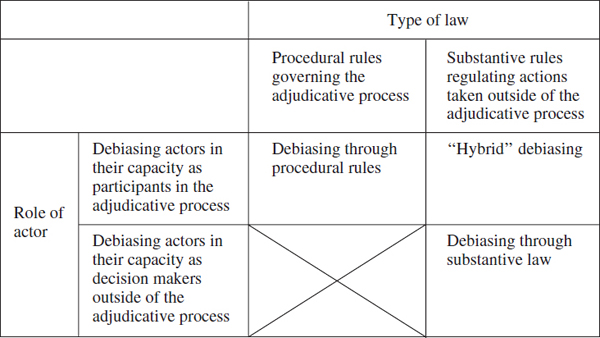

The example of debiasing through employment discrimination law and the earlier example from Babcock, Issacharoff and Loewenstein’s work of debiasing through restructuring the adjudicative process together illustrate the basic distinction between debiasing through substantive law and debiasing through procedural rules. Figure 4.1 generalizes the point by mapping the terrain of strategies for debiasing through law more fully. The column division marks the line between procedural rules governing the adjudicative process and substantive rules regulating actions taken outside of the adjudicative process. The row division marks the line between debiasing actors in their capacity as participants in the adjudicative process and debiasing actors in their capacity as decision makers outside of the adjudicative process. The upper-left box in this matrix represents the type of debiasing through law on which the prior work on such debiasing has focused: the rules in question are procedural rules governing the adjudicative process, and the actors targeted are individuals in their capacity as participants in the adjudicative process (Babcock et al. 1997; Peters 1999).

Figure 4.1. Typology of strategies for debiasing through law.

Moving counterclockwise, the lower-left box in the matrix is marked with an “X” because procedural rules governing the adjudicative process do not have any obvious role in debiasing actors outside of the adjudicative process—although these rules certainly may affect such actors’ behavior in various ways by influencing what would happen in the event of future litigation. The lower-right box in the matrix represents the category of debiasing through law emphasized in Jolls (forthcoming) and Jolls and Sunstein (2006a,b): the rules in question are substantive rules regulating actions taken outside of the adjudicative process, and the actors targeted are decision makers outside of the adjudicative process.

Finally, the upper-right corner of the matrix represents a hybrid category that warrants brief discussion, in part to demarcate it from the category (just discussed) of debiasing through substantive law. In this hybrid category, it is substantive, rather than procedural, law that is structured to achieve debiasing, but the judgment error that this debiasing effort targets is one that arises within, rather than outside of, the adjudicative process. For example, Farnsworth’s (2003) work on self-serving bias suggests that such bias on the part of employment discrimination litigants (actors in their capacity as participants in an adjudicative process) might be reduced by restructuring employment discrimination standards (substantive rules regulating action outside of the adjudicative process) to increase the reliance of such standards on objective facts as opposed to subjective or normative judgments. This type of debiasing through law operates through reform of substantive law rather than procedural rules, but the actions to be debiased are those of litigants within the adjudicative process. In the case of debiasing through substantive law, by contrast, both the legal rules through which debiasing occurs and the capacities in which actors are targeted for debiasing are distinct from the context of the adjudicative process.

In Richard Thaler’s view, the ultimate sign of success for behavioral economics will be that what is now behavioral economics will become simply “economics.” The same observation applies to behavioral law and economics. Debiasing through law, discussed in Section 4.5, may hasten the speed at which this transition occurs by pointing to a wide range of possibilities for recognizing human limitations while at the same time avoiding the step of paternalistically removing choices from people’s hands (Jolls and Sunstein 2006a). Because debiasing through law cannot be applied in every context, however, future work in behavioral law and economics should also seek to refine and strengthen analyses concerned with structuring legal rules in light of the remaining (post-debiasing) departures from traditional economic assumptions of unbounded rationality, willpower and self-interest.

Acemoglu, D., and J. D. Angrist. 2001. Consequences of employment protection? The case of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Journal of Political Economy 109:915–57.

Allais, M. 1952. Fondements d’une Théorie Positive des Choix Comportant un Risque et Critique des Postulats et Axiomes de L’Ecole Americaine. (Translated and edited by M. Allais and O. Hagen, 1979, as “The foundations of a positive theory of choice involving risk and a criticism of the postulates and axioms of the American school.” In Expected Utility Hypotheses and the Allais Paradox: Contemporary Discussions of Decisions Under Uncertainty, pp. 27–145, with Allais’s Rejoinder. Dordrecht: Reidel.)

Arkes, H. R., D. Faust, T. J. Guilmette, and K. Hart. 1988. Eliminating the hindsight bias. Journal of Applied Psychology 73:305–7.

Arnould, R. J., and H. Grabowski. 1981. Auto safety regulation: an analysis of market failure. Bell Journal of Economics 12:27–48.

Autor, D. H., and M. G. Duggan. 2003. The rise in the disability rolls and the decline in unemployment. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118:157–205.

Babcock, L., G. Loewenstein, S. Issacharoff, and C. Camerer. 1995. Biased judgments of fairness in bargaining. American Economic Review 85:1337–43.

Babcock, L., X. Wang, and G. Loewenstein. 1996. Choosing the wrong pond: social comparisons in negotiations that reflect a self-serving bias. Quarterly Journal of Economics 111:1–19.

Babcock, L., G. Loewenstein, and S. Issacharoff. 1997. Creating convergence: debiasing biased litigants. Law and Social Inquiry 22:913–25.

Bar-Gill, O., and O. Ben-Shahar. 2004. Threatening an “irrational” breach of contract. Supreme Court Economic Review 11:143–70.

Camerer, C., S. Issacharoff, G. Loewenstein, T. O’Donoghue, and M. Rabin. 2003. Regulation for conservatives: behavioral economics and the case for “asymmetric paternalism”. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 151:1211–54.

Camerer, C. F., and H. Kunreuther. 1989. Decision processes for low probability events: policy implications. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 8:565–92.

Coase, R. H. 1960. The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics 3:1–44.

Cutler, D. M., and J. Gruber. 1996. Does public insurance crowd out private insurance? Quarterly Journal of Economics 111:391–430.

Dasgupta, N., and A. G. Greenwald. 2001. On the malleability of automatic attitudes: combating automatic prejudice with images of admired and disliked individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81:800–14.

Dasgupta, N., and S. Asgari. 2004. Seeing is believing: exposure to counterstereotypic women leaders and its effect on the malleability of automatic gender stereotypes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 40:642–58.

DeJoy, D. M. 1989. The optimism bias and traffic accident risk perception. Accident Analysis and Prevention 21:333–40.

Donohue III, J. J., and J. Heckman. 1991. Continuous versus episodic change: the impact of civil rights policy on the economic status of blacks. Journal of Economic Literature 29:1603–43.

Dovidio, J. F., K. Kawakami, and S. L. Gaertner. 2002. Implicit and explicit prejudice and interracial interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82:62–68.

Ellsberg, D. 1961. Risk, ambiguity, and the Savage axioms. Quarterly Journal of Economics 75:643–69.

Elster, J. 1979. Ulysses and the Sirens: Studies in Rationality and Irrationality. Cambridge University Press.

Farnsworth, W. 2003. The legal regulation of self-serving bias. U.C. Davis Law Review 37:567–603.

Ferrell, A. 2003. Mandated disclosure and stock returns: evidence from the over-the-counter market. Harvard Law and Economics Discussion Paper 453.

Fischhoff, B. 1982. Debiasing. In Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (ed. D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, and A. Tversky), pp. 422–44. Cambridge University Press.

Gaertner, S. L., and J. P. McLaughlin. 1983. Racial stereotypes: associations and ascriptions of positive and negative characteristics. Social Psychology Quarterly 46:23–30.

Gewertz, K. 2003. Adding some color to Harvard portraits. Harvard University Gazette (May 1), p. 11.

Gompers, P. A., J. L. Ishii, and A. Metrick. 2003. Corporate governance and equity prices. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118:107–55.

Greenstone, M., P. Oyer, and A. Vissing-Jorgensen. 2006. Mandated disclosure, stock returns, and the 1964 Securities Acts Amendments. Quarterly Journal of Economics 121:399–460.

Greenwald, A. G., D. E. McGhee, and J. L. K. Schwartz. 1998. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74:1464–80.

Gruber, J. 1994. The incidence of mandated maternity benefits. American Economic Review 84:622–41.

Gulati, M., and M. Yelnosky. Forthcoming. Behavioral Analyses of Workplace Discrimination. Kluwer Academic.

Guppy, A. 1993. Subjective probability of accident and apprehension in relation to self–other bias, age, and reported behavior. Accident Analysis and Prevention 25:375–82.

Güth, W., R. Schmittberger, and B. Schwarze. 1982. An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 3:367–88.

Guthrie, C. 2003. Prospect theory, risk preference, and the law. Northwestern University Law Review 97:1115–63.

Heckman, J. J., and B. S. Payner. 1989. Determining the impact of federal antidiscrimination policy on the economic status of blacks: a study of South Carolina. American Economic Review 79:138–77.

Hoffman, E., and M. L. Spitzer. 1982. The Coase Theorem: some experimental tests. Journal of Law and Economics 25:73–98.

——. 1986. Experimental tests of the Coase Theorem with large bargaining groups. Journal of Legal Studies 15:149–71.

Issacharoff, S., and G. Loewenstein. 1995. Unintended consequences of mandatory disclosure. Texas Law Review 73:753–86.

Jolls, C. 1997. Contracts as bilateral commitments: a new perspective on contract modification. Journal of Legal Studies 26:203–37.

——. 1998. Behavioral economics analysis of redistributive legal rules. Vanderbilt Law Review 51:1653–77.

——. 2002. Fairness, minimum wage law, and employee benefits. New York University Law Review 77:47–70.

——. 2004. Identifying the effects of the Americans with Disabilities Act using state-law variation: preliminary evidence on educational participation effects. American Economic Review 94:447–53.

——. Forthcoming. Antidiscrimination law’s effects on implicit bias. In Behavioral Analyses of Workplace Discrimination (ed. M. Gulati and M. Yelnosky). Kluwer Academic.

Jolls, C., and C. R. Sunstein. 2006a. Debiasing through law. Journal of Legal Studies 35:199–241.

——. 2006b. The law of implicit bias. California Law Review 94:969–96.

Jolls, C., C. R. Sunstein, and R. Thaler. 1998. A behavioral approach to law and economics. Stanford Law Review 50:1471–1550.

Kahneman, D., and S. Frederick. 2002. Representativeness revisited: attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. In Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment (ed. Th. Gilovich, D. Griffin, and D. Kahneman), pp. 49–81. Cambridge University Press.

Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky. 1979. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47:263–91.

Kahneman, D., J. L. Knetsch, and R. Thaler. 1986a. Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: entitlements in the market. American Economic Review 76:728–41.

——. 1986b. Fairness and the assumptions of economics. Journal of Business 59:S285–300.

——. 1990. Experimental tests of the endowment effect and the Coase Theorem. Journal of Political Economy 98:1325–48.

Kaplow, L., and S. Shavell. 1994. Why the legal system is less efficient than the income tax in redistributing income. Journal of Legal Studies 23:667–81.

——. 2002. Fairness versus Welfare. Harvard University Press.

Katz, L. F., and B. D. Meyer. 1990. Unemployment insurance, recall expectations, and unemployment outcomes. Quarterly Journal of Economics 105:973–1002.

Kelman, M. 1979. Consumption theory, production theory, and ideology in the Coase Theorem. Southern California Law Review 52:669–98.

Korobkin, R. 1998. The status quo bias and contract default rules. Cornell Law Review 83:608–87.

——. 2003. The endowment effect and legal analysis. Northwestern University Law Review 97:1227–93.

Kuran, T., and C. R. Sunstein. 1999. Availability cascades and risk regulation. Stanford Law Review 51:683–768.

Laibson, D. 1997. Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. Quarterly Journal of Economics 112:443–77.

Lichtenstein, S., P. Slovic, B. Fischhoff, M. Layman, and B. Combs. 1978. Judged frequency of lethal events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory 4:551–78.

Loewenstein, G., and D. A. Moore. 2004. When ignorance is bliss: information exchange and inefficiency in bargaining. Journal of Legal Studies 33:37–58.

Loewenstein, G., S. Issacharoff, C. Camerer, and L. Babcock. 1993. Self-serving assessments of fairness and pretrial bargaining. Journal of Legal Studies 22:135–59.

McConnell, A. R., and J. M. Leibold. 2001. Relations among the implicit association test, discriminatory behavior, and explicit measure of racial attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 37:435–42.

Macrae, C. N., G. V. Bodenhausen, and A. B. Milne. 1995. The dissection of selection in person perception: inhibitory processes in social stereotyping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69:397–407.

Nosek, B. A., M. R. Banaji, and A. G. Greenwald. 2002. Harvesting implicit group attitudes and beliefs from a demonstration website. Group Dynamics 6:101–15.

Peters, P. G. 1999. Hindsight bias and tort liability: avoiding premature conclusions. Arizona State Law Journal 31:1277–314.

Plott, C. R., and K. Zeiler. 2005. The willingness to pay–willingness to accept gap, “endowment effect,” subject misconceptions, and experimental procedures for eliciting valuations. American Economic Review 95:530–45.

Posner, E. A. 1995. Contract law in the welfare state: a defense of the unconscionability doctrine, usury laws, and related limitations on the freedom to contract. Journal of Legal Studies 24:283–319.

Posner, R. A. 1979. Utilitarianism, economics, and legal theory. Journal of Legal Studies 8:103–40.

——. 1989. An economic analysis of sex discrimination laws. University of Chicago Law Review 56:1311–35.

——. 1992. Economic Analysis of Law, 4th edn. Boston, MA: Little Brown.

Rabin, M. 1993. Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. American Economic Review 83:1281–1302.