If one examines the salient economic institutions of the health sector, one might expect that sector to be a breeding ground for applied behavioral economics. Consider a set of economic activities where addictions figure prominently; where consumers have limited information that they must use to make choices in the context of fear, urgency, and trust in an expert; and where the services used are often credence goods (Emons 1997) whose applications are frequently governed by professional norms and habit. In such an economic environment, the methods of behavioral economics might be expected to be prevalent in modifying traditional models to take account of those features that appear to conflict with simple notions of rationality in economic behavior. Yet the application of behavioral economics to issues in health economics has been largely confined to understanding addictive behavior around cigarettes, drugs, and alcohol (see, for example, Becker and Murphy 1988; Gruber and Koszegi 2001; Loewenstein 2001; O’Donoghue and Rabin 1999; Schoenbaum 1997).

Research on addictions has its origins in research on household production and the demand for good health (Becker 1964; Grossman 1972). Decisions about substance abuse involve a set of harmful health choices that appear to represent extreme tradeoffs between today’s pleasures and tomorrow’s health and well-being. A substantial amount of progress has been made in both theoretical analysis and empirical testing of models in this area, and a lively program of research that encompasses behavioral economic concepts is underway.

In this chapter I draw on a different research tradition, which emanates from the seminal paper by Arrow (1963). The efficiency of health insurance markets, doctor–patient relationships, and the role of nonmarket institutions in promoting efficiency were raised by Arrow and continue to be central issues in the health economics research program. This side of health economics has received far less attention from scholars armed with the tools of behavioral economics than the addictions area. I focus on decision-making about treatment of illness, rationing of health services, and markets for health insurance.

I argue that behavioral economics may be particularly important for modifying neoclassical approaches because, as in many areas of the economy, people appear to make choices about health care that are situation- or context-specific, resulting in cognitive errors and failures to optimize. The health sector is also characterized by institutions and decision-making circumstances that, in addition to making cognitive errors more likely, create friction that impedes market adjustments that may lead to correction of errors over time (Glaeser 2003; Mullainathan and Thaler 2001). These include the stress of decision-making about one’s health, professionalism, and a lack of information about medical care. The paper is organized into four sections. This introductory section sets the intellectual context for the review. The second section focuses on physician behavior, which represents a large class of problems in the health sector, where I believe behavioral economics has much to contribute. The third section addresses some puzzles in health economics related to demand behavior and the behavior of health insurance markets. The final section offers some concluding observations and comments on normative issues in health economics.

Arrow’s (1963) paper seeks to explain the health sector’s institutions as a response to the special features of health care and health insurance. Among the special characteristics are information asymmetry and the significance of medical care in human affairs. The research program stemming from Arrow’s work has produced great understanding of health-care delivery. Among the issues at the heart of the research program have been: market failure in health insurance due to moral hazard and adverse selection; the significance of the nonprofit organizational form in health care; and the role of institutions such as professional norms, trust, and morality in medical markets.

Applying traditional economic models that rely on rational utility-maximizing consumers and physicians and efficient market equilibriums has been highly productive both theoretically and empirically, and has contributed to the design of public policy in health care (Culyer and Newhouse 2000). For example, research on hospital payment methods has advanced notably and has been very influential in public policy debates (Newhouse 2003). Yet the application of traditional models has also repeatedly faced puzzles that have served as intellectual impasses. It is in attending to such puzzles that the ideas of behavioral economics may be particularly useful in advancing the analysis of health-care markets and institutions. In the next section I focus on markets for physician services and some puzzles found in those markets. I believe that these issues are representative of broader issues in the economics of the health sector.

Early in his essay, Arrow (1963, p. 949) remarked:

It is clear from everyday observation that the behavior of sellers of medical care is different from that of businessmen in general.

No area in health economics relies on a vocabulary that is more closely linked to the work of behavioral economics than research on physician behavior. As Pauly (2001) notes, Arrow used words such as “trust” and “morals” to discuss physician behavior. These are words that tend to make economists uncomfortable.

Some of the first econometric studies of health-care markets took aim at the market for physicians’services (Feldstein 1970; Newhouse 1970; Fuchs and Kramer 1972). These studies took the competitive model as their point of departure. Each obtained results showing a positive partial correlation between the physician stock in a market and physician prices: a finding inconsistent with the competitive model. These papers set off a line of research on models of physician behavior that continues to this day. The first reactions to the surprising results were to suspect monopoly in the physicians’ market (Newhouse 1970; Frech and Ginsburg 1972). Further analysis found the evidence to be inconsistent with both monopoly and competitive models. Health economists rapidly developed a set of ad hoc explanations grounded in motivations of physicians that departed from profit maximization. Yet, as McGuire (2000) notes, “there is no agreeable alternative” model to that of profit maximization.

Feldstein (1970) sought to explain the apparent departure from simple profit maximization. He argued that physician markets experience persistent excess demand. He proposed that the reason for this is that physicians deliberately set prices below market clearing levels to enable them to choose the most “interesting cases” from among the patient pool. This explanation was not grounded in any evidence about physician motives or the details of medical practice. A second explanation attempted to import an early behavioral economics idea, namely the satisficing model (Simon 1958). Newhouse (1970) and Evans (1974) suggested that physicians might set prices so as to achieve a “target income” in part because maximizing behavior may be seen as socially undesirable. Arrow (1963) first raised this point by observing approvingly that sociologists had argued for a “collectivity orientation” of physicians that would lead them away from profit-maximizing behavior. Evans (1974) proposed that the target income level was set relative to the local income distribution.

Careful analysis of the target income model reveals a variety of shortcomings (McGuire 2000). The basis for establishing the “target” was quite fuzzy. In addition, the “target” is merely an objective. There are numerous ways of hitting the target; the theory does not explain which approach will be taken. A complete model also requires a rule of choice for pursuing the objective. The target income model is typically specified in the context of a monopolistically competitive market structure, where physicians choose a price that will achieve a target income and meets demand. This model setup yields multiple equilibria that are unstable, resulting in dramatic swings in prices in response to small changes in physician supply. In sum the target income model might be viewed as a “false start” in linking behavioral economics and health economics.

A different modeling approach introduced the notion of “physician-induced demand” in the context of a model of utility maximization. Evans (1974) posited that physicians create demand for their own services by exploiting their role as an agent for the incompletely informed patient. That is, physicians are imperfect agents in that they will recommend treatment beyond the “patient’s optimum level” in order to gain income. Medical uncertainty and asymmetric information all serve to reinforce this conception of physician behavior. This model treats demand inducement in a manner akin to how advertising is introduced into market models. That is, demand inducement is a shifter in the demand function facing the doctor. The ability to induce demand is also specified as an argument in the physicians’ objective function, so that exploiting the agency relation for self-interest reduces physician utility.2 This device serves to constrain an otherwise unbounded ability to shift demand.

While intuitively appealing, given the importance of the agency relation between physician and patient, little research has been done to understand the forces underlying the ability to induce demand as proposed in these models (McGuire 2000; Reinhardt 1978; Fuchs 1978). Most discussions of demand inducement appeal intuitively to notions of medical ethics and trust between doctors and patients; poor information, fear, and anxiety on the part of patients; and uncertainty in medical choices. The behavioral economics literature has explored how some of these circumstances and others affect decision-making and economic behavior (Rabin 1998). Demand inducement may well result from a number of psychological features of doctors and patients operating in health-care markets. There are a number of additional constructs in behavioral economics, such as self-serving behavior, wishful thinking, and the impact of the desire by patients to avoid regret, that might contribute to what appears as demand inducement (Rabin 1998; Thaler 1980). The application of these concepts leads one to consider in greater detail the nature of doctor–patient interactions in the context of models of physician decision-making.

Physicians are highly educated and skilled professionals who are motivated to serve their patients in order to improve their health and well-being. They are also frequently in positions in which they face great clinical uncertainty and must persuade patients to pursue one clinical course over others. Physicians have been shown to be creatures of habit in making medical choices, and are slow to adopt new practices and technologies that would improve the quality of care and, in turn, their patients’ health (Institute of Medicine 2001). Specifically, a series of studies have shown that, in treating conditions like otitis media, diabetes, depression, and asthma, physicians regularly depart from evidence-based practice (Institute of Medicine 2001, Appendix A). This runs counter to what one might expect from market models that assume either profit maximization or maximization of a physician objective function that might include patient health benefits and income as arguments.

For example, physicians in the United States do not gain financially based on the specific drugs they choose to prescribe for their patients. Therefore one might expect physicians to choose the most cost-effective drugs on behalf of their patients, thereby serving as a “perfect agent.” Yet physicians have been observed to be habitual in their choice of pharmaceutical agents, relying on drugs they became familiar with in medical training or learned about through pharmaceutical promotions. This has meant a reluctance to use more effective new drugs or lower cost versions of older drugs (generics) (Hellerstein 1998). Also, physicians have been slow to prescribe drugs that have been widely shown to improve health outcomes, such as beta-blockers for patients following a heart attack (Institute of Medicine 2001).

Health economists attempting to address such puzzles have frequently appealed to the costs of learning about new drugs and procedures. Empirical research on the simplest substitution choices in prescription drugs, that between branded and generic versions of the same drug, show a great heterogeneity in willingness to substitute that is unexplained by factors clearly associated with experience or learning costs (Hellerstein 1998). Thus, simple extensions of the profit or utility-maximizing models have not produced satisfactory explanations of basic clinical choices.

A hallmark of medical decision-making is choice under uncertainty. Arrow’s (1963) paper begins with this premise. Microeconomic models of physician decision-making that follow in the tradition of Arrow recognize that there is uncertainty about the effectiveness of any medical technology and there is heterogeneity in patient responses to treatment and preferences about care and how the process of care will unfold. In this section, a simple model of physician behavior is set out that will enable us to examine some potential contributions of behavioral economics to modifying the model. I adopt the model of physician behavior and notation of McGuire (2000) in his review of Physician Agency.

A patient is assumed to benefit from the receipt of medical care (m) according to the function B = B(m), where B′ > 0 and B″ < 0. The negative second derivative occurs because of diminishing marginal utility of health status and because the health production function H = H (m) has a negative second derivative. We can therefore restate the benefit function to capture both of these effects as B(m) = V (H (m)). Generally, it is assumed that V″ < 0, which implies risk aversion.3 McGuire (2000) introduces uncertainty as a simple additive term to the health production function H (m). In an uncertain medical decision-making context, a patient’s benefits from medical care are viewed as expected benefits:

where u is a random error with mean 0 and variance σu.4 One implication pointed to by McGuire (2000) is that if the degree of absolute risk aversion is decreasing in income then the expected benefits of using medical care, m, rises with the level of uncertainty (σu). The implication of this observation is that patients will appear to demand “too much” medical care when judged in terms of ex post marginal contributions to health outcomes. The excess use of medical care can be seen as an attempt by uncertain patients to protect themselves against uncertain medical care.

Markets for medical care are characterized not only by uncertainty but also by asymmetric information between physician and patient. Most approaches to paying doctors in medical markets implicitly assume that outcomes are “noncontractible,” that is, it is impractical to pay doctors on outcome (Dranove and White 1987).5 Thus, most health-care markets make use of payment arrangements in which doctors are rewarded for performance through retention of patients or by attracting new patients. The vast majority of physician services are paid for either via capitation contracts (per person per year payment) or under fee for service arrangements. In either case, the physician is rewarded for having a higher volume of patients seeking his or her services (Kaiser Family Foundation 2003). Thus, if patients choose doctors or decide to stay with doctors based on performance, then physicians will have an incentive to undertake unobserved actions to improve quality and performance.

Because the health production function is affected by service delivery, physician effort, and other factors, an individual patient’s observation of performance does not allow them to easily identify the level of effort supplied by a physician. This agency problem has been a long-standing concern for health economists. Asymmetric information is captured in McGuire’s (2000) formulation by restating the benefit function to include physician effort, B = B(m, e, u), where e represents physician effort. It is assumed that e is not observable and is therefore noncontractible. So the patient is assumed to know the relationships in B(·) and to observe m and the outcome of treatment, B0. A patient is assumed to make Bayesian decisions.6 Suppose we consider a situation where a physician’s effort can be characterized as a simple dichotomous act. For example, a physician can read the literature on treatment for a condition presented by the patient. The Bayesian patient can make an inference about e based on observing m and B0.7 The inference can be viewed as a likelihood that a high level of effort was taken, L1(B0, m). The likelihood that the proper effort was not taken is L0 = 1 − L1. The physician’s profit-maximization problem with asymmetric information can be described as

where n is the number of patients seen by the physician and the term in the second set of brackets is a general statement about revenue and costs that encompasses the continuum of payment arrangements commonly used to pay doctors. These range from a capitation payment, where R > 0 and p = 0, to fee-for-service payments, where R = 0 and p > 0. If the patient infers that effort e = 1 and believes that the physician will typically undertake the desired effort then observing outcome will provide useful information. In this model incentives for quality care (high level of effort) are created by the demand response n(∂n/∂e). It is also important that the payment systems are set up so that physician earnings are affected by the demand response to inferences about effort levels taken by the physician.

The degree of demand response is central to determining the efficiency of health-care markets. The model summarized above, for example, offers an underpinning to the demand inducement model discussed earlier (Dranove 1988). That is, the doctor might misrepresent information to a patient, leading them to believe the marginal product H′ of a particular course of treatment is higher than it is in reality. The result is a higher level of demand for m than is efficient. This approach is similar to that taken in the optimal fraud literature and presumes a manipulative physician acting in a calculated self-interested manner even at a possible health cost to the patient. McGuire (2000) and others note that medical treatments frequently involve a sequence of interactions between doctor and patient that may allow a patient to learn about outcomes during the course of treatment. This may permit a patient to respond to physician actions in a manner that rewards effort.

A different modeling tack assumes that quality is an attribute of the physician that is not a matter of choice during a patient encounter. That is, e is a fixed attribute. This type of model has been used as an alternative to those of physician-induced demand (Pauly and Satterthwaite 1981). The implication of this view is that doctors are an experience good that can only be judged by sampling by a consumer or a trusted source of information (friend or family). Thus, in markets where there is a higher concentration of physicians, less may be known about any one physician, which may result in establishing market power for a doctor who is known to a patient. The implication is that an individual physician’s demand curve is steeper in markets with more doctors, allowing them to charge higher prices. Such a model is used to explain why prices for physician’s services are higher in markets with more physicians without resorting to demand inducement. Why adding a physician to the choice set would necessarily dilute information except in an average sense is unclear. For example, why would I know less about my doctor because other doctors moved into town? The approach illustrates how health economists have gone to considerable lengths to adapt the standard model to stylized facts in the health-care market place.

Behavioral economics has frequently raised questions that go to the heart of the model set out in Equation (6.2), above: max π = n(L1)R + (p − c)m. Patient demand response is key to the transmission of incentives. The model posits that patients will choose a physician based on Bayesian inferences about effort made by the doctor. This requires that patients form a prior about a doctor’s willingness to exert effort (an initial impression prior to contact) and engage in an updating process (following an initial contact) that assumes separation between previous judgments about the likelihood that high effort is undertaken and the evaluation of new evidence from, say, a new episode of care (Camerer and Loewenstein 2003). The health sector offers a unique institutional environment within which to view these decisions. When the institutional arrangements are combined with key concepts from behavioral economics a new view of market outcomes in the health sector begins to emerge.

Consider how people make choices about physicians and the sources of information used to make judgments about the quality of a physician. The methods by which patients obtain information about doctors prior to an initial contact and referrals are obtained play central roles in the formation of priors about doctor quality and willingness to exert effort. Most patients are close to fully insured, carrying cost sharing of 20% or less for physician services. The health sector in recent years has been characterized by expanded public availability of information on provider performance. State governments have published performance data on surgeons and hospitals. Local magazines and newspapers regularly report lists of top-ranking physicians. The Internet has increased the availability of information on hospitals, physicians and their practices. This expansion of information is part of a deliberate strategy to boost consumerism, improve market efficiency and presumably quality in health care (Shaller et al. 2003). Yet recent surveys of consumers show that 70% of people have not seen any information on the quality of providers (Kaiser Family Foundation 2000). These same surveys reveal that 70% of people report that they rely on family and friends and 65% on their usual physician as their most reliable sources of information on other providers of health care and their quality. In addition, patients report that they prefer providers with whom they are familiar. For example, 76% of survey respondents say they would choose a surgeon that they are familiar with over one that was more highly rated by experts such as state government or accrediting organizations.

The implications of these data are that the basis upon which priors about quality and performance are formed is the recounted experience of friends and relatives and to a lesser extent a regular doctor. Patients also put great weight on familiarity with a physician, presumably based on a relatively small number of positive interactions. In the case of choosing a primary care physician the reliance on friends and family is likely to be more important, since the choice suggests that there may be no regular doctor or that the relationship with the regular physician may not be satisfactory. This decision-making context is ripe for the types of situational influences on economic choices that are the focus of behavioral economics.

Tversky and Kahneman (1973) refer to an availability heuristic in order to describe the reliance on more vivid or memorable evidence to construct a prior about the probability that a physician is high quality or will exert adequate effort. Akerlof (1991) calls the phenomenon “salience.” Given the data cited above, it is likely that personal reports will be relied upon over examination of systematic information collected on health-care qualifications or performance. Personal testimonials on the multidimensional service provided by physicians will be far more available than any systematic data-reporting system. Reliance on reports from family and friends may create distortions in perceived quality because of what is most memorable in personal reports. Consumers of health care have been shown to be good reporters of certain attributes of care and weakly aware of others. For example, patients have been shown to accurately report information on whether a physician was respectful, attentive, clear in explaining clinical issues, and had operated a clean and efficient office. These same patients were found to be inaccurate in reporting of the technical quality of care. That is, they were not accurate in judging whether a physician supplied appropriate evidence-based treatment (Edgman-Levitan and Cleary 1996). It has also been shown that the dimensions of care that consumers understand and can accurately report are not highly correlated with so-called technical aspects of quality care (Cleary and Edgman-Levitan 1997). The implication here is that patients will commonly develop a prior about a primary care physician by relying on reports from family and friends based on observations about some dimensions of medical care and perhaps not on the dimensions that most directly affect their health outcomes. Applying notions of an availability heuristic that focuses on one dimension of physician performance in the formulation of priors on quality expands the conception of demand and demand response in markets for physician services. This offers one promising avenue for better linking of market models to the observed behavior in health care.

The decision-making environment in health care also offers a context where the formation of priors about providers of medical care may be subject to the “law of small numbers” bias (Rabin 1998, 2002). Rabin (2002) explains that when economic agents believe in the “law of small numbers” they overinterpret the extent to which information from observing a small number of events reflects the experience of the “population” from which those events are drawn. In the case of medical markets, priors about a physician may be formed based on reports from friends, family, and physicians. The reports from friends and family will typically be based on a relatively small number of encounters with a medical professional. Referrals from a physician may also be based on a relatively small number of experiences.8 In fact, health-care consumers regularly report that they have greater confidence in sources of care that are likely to rely on small numbers than they do in sources that rely on large representative samples such as accreditation agencies and health plan sponsors. National survey data also suggest a high degree of confidence by consumers that they have sufficient information to make the “right” choices about medical procedures and providers. Eighty-one percent of consumers stated they had enough information to make the right choice about a treatment option and 79% said they had enough information to make the right choice of doctor (Kaiser Family Foundation 2000).9 A key implication of a model that views consumers as believing in the law of small numbers is that priors will reflect too much confidence in an opinion formed about the quality or performance of a health-care provider (Rabin 2002).

The Bayesian consumer is assumed to assess new evidence on the performance of a health-care provider independently of the established priors on the quality of a provider. This feature of the model applies to physician encounters that are repeated, such as those with a primary care physician or a specialist treating a chronic illness. The contrasting case is a specialty surgery, where the physician choice would not involve an updating process. Health-care markets are characterized by a set of institutions and circumstances that might lead consumers to filter information so as to conflict with the Bayesian updating assumption. Arrow (1963) notes that trust is a central feature of the doctor–patient relationship. Giving trust this important role stems from the uncertainty and vulnerability of the patient. Trust is offered up as a nonmarket institution that increases efficiency by reducing the disutility and inefficiency from the uncertainty and the anxiety of illness, as well as the agency problems associated with the asymmetry of information between doctor and patient.10 The health sector is replete with complementary institutions that aim to increase trust between medical providers and patients. These include a code of medical ethics, medical education, professionalism, licensure, and, in the case of hospitals, nonprofit status. Trust is also recognized as an ingredient of treatment affecting the well-being of a patient.

Studies of the prevalence of trust show that patient trust in their doctors remains very high across income, demographic, and health-related social strata (Hall 2001). Some psychological research on the doctor–patient relationship shows a willingness to interpret data showing poor outcomes of treatment as unavoidable events beyond the physician’s control (Ben Sira 1980). This raises the question of how patients will use new information to make inferences about the physician effort parameter in the benefit function B = B(m, e, u). Recall that, in the model of doctor–patient interaction set out above, the Bayesian patient estimates the likelihood that appropriate effort will be taken, L1(B0, m). Thus, we consider how this likelihood will be formed. The filtering function of the trust relationship is related to what Rabin and Schrag (1999) refer to as confirmation bias. For example, does the confidence in a physician generated by a referral from a trusted friend, relative, or physician (the prior) serve as a filter for interpreting new information about a physician? Applying a quasi-Bayesian updating process (i.e., efficiently applying Bayes’s rule to biased information) like that proposed by Rabin and Schrag would result in patients misinterpreting certain outcomes as not being a reflection of physician quality or the level of effort exerted. The misinterpretation of physician effort or quality would most likely stem from erroneous interpretation of treatment outcomes or misperception of the nature of the production function for health. Extant literature in health psychology points to patients’ perceptions about the production function as being potentially key in confirmatory bias in drawing inferences from poor outcomes by a trusted physician.

Core concepts in behavioral economics seem to fit well with institutions that govern the flow of information and evidence on the manner in which patients use information to make choices. The psychology of forming priors and Bayesian updating, discussed above, points to hypotheses about the nature of demand response to quality signals in markets for medical care. One hypothesis that emerges from applying behavioral concepts to the formation of priors is that the quality signal based on extant market information, or even improved public reporting of quality, may not yield strong demand response to quality signals, as has generally been assumed. The normative implication is that improved information may not result in an efficient quality equilibrium in the market unless some other institution is introduced that overrides the type of patient decision-making we have described (e.g., employers guiding provider choice based on systematic data). Integrating behavioral economics into models of physician behavior would result in different specifications of econometric models of physician services. For example, the degree of demand response might be expected to depend on how patients reach a physician. Those who were referred by family or a physician would be expected to respond differently to quality signals than those referred by a health plan or the local medical society.

Medicine is, I have found, a strange and in many ways disturbing business. The thing that still startles me is how fundamentally human an endeavor it is.

Gawande (2002)

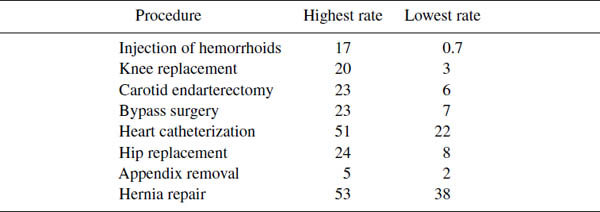

Embedded in the model of physician behavior set out above is a process by which a physician chooses among a complex set of possibilities to treat a particular patient or type of patient. A physician’s choices (assuming profit maximization) depend on her view of the production function, which has also been characterized as a Bayesian learning process (Phelps and Mooney 1993). These models recognize the institutions through which physicians learn after completion of their training. Key sources of learning are peers with whom a physician practices (partners, fellow employees, peers on a hospital staff), continuing medical education courses, pharmaceutical promotion personnel, and medical journals. The application of traditional Bayesian updating models has emphasized local sources of information because they are asserted to be low-cost sources of learning (Phelps 2000). These models have been used to explain the persistent variation across geographic areas in the use of medical procedures that cannot be explained by patient illness characteristics, demographics, or indicators of preferences.

For example, in 1999 Medicare spending was $9,941 per enrollee in Miami, FL, and $4,886 in Minneapolis, MN. The difference cannot be accounted for by health or demographics factors such as age, gender, and race, or differences in medical care prices. Instead, the spending variation is mostly due to more frequent physician visits, diagnostic tests, and hospitalizations and procedures (Wennberg and Cooper 1997). Consistent with this, Phelps (2000) reports coefficients of variation in hospitalization rates across New York State. He shows that coefficients of variation for conditions such as pediatric otitis media, depressive neurosis, and chronic obstructive lung disease were 0.49, 0.42, and 0.35, respectively. These contrast with services where little discretion can be exercised, such as heart attacks, where the coefficient of variation was 0.12.

In the Bayesian updating model of physician choice of treatment technology, the prior about the appropriate use of a particular procedure to treat a specific illness (e.g., cesarean section for deliveries) is formed in medical training (medical school and residency) according to the observed share of total cases of a given illness treated with the procedure. The physician is then assumed to combine new local observations with prior information, giving each case equal weight in order to form the posterior distribution. The result is a weighted average of accumulated observations from medical training and subsequent practice. This model can be used to explain how a “local style” of medical practice can persist and why adoption of new treatments may be slow.

In this model it is assumed that the Bayesian physician overweights information from local sources or that data from medical journals or medical conferences get ignored or are given little weight when assessing the use of medical technologies. Phelps and Mooney (1993) argue that low-cost local sources of information are emphasized. They also note the importance of personal advice from colleagues about how to apply specific medical techniques. This latter point is consistent with the availability heuristic, where people tend to overemphasize more vivid personal descriptions of successes and failures than perhaps more representative reports of data from the literature.

Another behavioral construct that is potentially relevant for understanding why local opinions should receive such high weight is the notion of regret (Thaler 1980). Physicians commonly must choose from among many competing approaches to treating a particular condition and trusting patients rely centrally on the recommendations of the physician. This makes the physician largely responsible for the consequences of the complex choice. Moreover, these choices are commonly made under considerable time pressure. The typical physician visit is about fifteen minutes. Thus, the potential for regret is high and the physician has incentives to attempt to lower the responsibility costs of medical decision-making. One institution that has long been recognized as an important influence on physician behavior is the professional norm (Arrow 1963). In this case the norm might be viewed as the local approach to treatment that a physician can point to as guiding her choices. In the event of a poor outcome, the physician that practices according to local norms can note that they followed standard operating practices, whereas they could more easily be individually tied to a choice if they departed from local practice (Thaler 1980). Giving great weight to local data therefore reduces responsibility costs and might therefore help explain the particular way that Bayesian updating works in medical decision-making. These behavioral influences on decision-making are reinforced by local health plan attempts to affect practice patterns through local profiling of physicians.11

This Bayesian physician decision model has been coupled with ideas about how innovations take hold in order to also explain the establishment and persistence of geographic differences in patterns of treatment. The existence of this variation that is unexplained by patient characteristics or outcome implies substantial differences in economic welfare across markets that are not competed away. While not formally acknowledged, ideas from behavioral economics are at least casually invoked in some of this literature. In one example, Phelps (2000) speculates about why different markets might differentially perceive the value of a new medical technique. He proposes that a physician innovator might be exposed to a new technique through the medical literature or by attending a conference. She tries out the new technique on twenty cases and then makes a judgment about whether the new technique is “better” than existing treatment methods. Phelps (2000) notes in passing that the physician may not be entirely unbiased because they are invested in the new method. This scenario highlights the potential relevance of the law of small numbers in creating very different views of a particular medical procedure across geographic areas based on a tendency to overinterpret the results from a small trial. It also suggests the potential role for confirmatory bias or filtering of data among physician innovators and adherents of older methods. These ideas can be applied to a Bayesian model of decision-making to help explain the high degree of variation in patterns of treatment across geographic areas and the slow adoption of many new and effective treatment technologies.

The empirical implications of this line of thinking lead to the view that it would be important to include data reflecting a physician’s own experiences and those of the immediate community in econometric analyses of physician treatment patterns. These factors may also be important in understanding diffusion of new technologies and reduced use of dominated technologies (sometimes referred to as “exnovation”). Such measures have typically not been included in econometric models of physician behavior.

A recent natural experiment highlights the potential contribution of the ideas set out above. In 1989 the New York State Department of Health initiated a program that would use market forces to improve the quality of care for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) surgery. The idea was that, by improving the standardization, reliability, and availability of information on physician- and hospital-specific outcomes, consumers who are largely insured would be better equipped to make choices based on performance. That is, demand response to outcome signals would discipline poorly performing providers of care and would improve quality of care. The State Department of Health developed a very detailed approach to “risk adjustment” of mortality outcomes for both physicians and hospitals, so that outcomes would be standardized for systematic patient mortality risk.12 Beginning in November 1992, mortality data were released publicly on surgeons performing 200 or more operations per year at one hospital. The Department of Health took great pains to inform the media on issues of quality improvement and interpretation of risk-adjusted mortality rates. The surgeon-specific mortality rates were published in major newspapers, including the New York Times and Newsday.

Two initial observations were made that pose a puzzle for health economists. The first is that risk-adjusted mortality rates associated with CABG declined from 4.17% in 1989 to 2.45% in 1992 (Chassin et al. 1996). The second is that no demand response was observed. There were no significant shifts in patient volume from surgeons and hospitals with relatively high mortality rates to those with low rates (Schneider and Epstein 1998). This was initially thought to be a result of the low awareness of the mortality reports among the public. Subsequent analyses that reexamined patient volume changes at points later in time, when public awareness of the mortality data was higher, show no evidence of significant demand response to the new information.

Little attention from health economists has been accorded the demand response result that represents a challenge to basic models of quality competition in health like the one set out above and like that of Dranove and Satterthwaite (1992). Some facts about doctor–patient roles in decision-making suggest some direction for applying behavioral economics ideas. Data reported above and elsewhere suggest that patients place the greatest weight on recommendations of friends, family, and primary care doctors. The patient appears to become even more reliant on the known professional when making choices about treatments for severe medical conditions. Research on the division of labor in medical decision-making shows that, for medical conditions such as breast cancer and colorectal cancer, the majority of patients prefer the physician to make the treatment decision (78% for colorectal cancer and 52% for breast cancer). In addition, only 20% of the breast cancer patients wanted to be actively involved as opposed to sharing decision-making (Beaver et al. 1999). This research also shows that, when faced with major procedures such as surgery, patients often prefer to be informed but want the physician to make key treatment decisions. In fact, a substantial number of patients report being pushed into more active roles in decision-making than preferred. Such evidence is consistent with the importance of trust in forming priors and the idea of regret as a limiting factor in people playing an active “consumer” role. Patients frequently appear not to want to carry the consequences of having made a choice if outcomes are poor.

Economics research has instead focused on selection incentives on the supply side and how the reduction in mortality observed should be interpreted (Dranove et al. 2002). The arguments advanced have been that physicians are risk averse, presumably to a loss of reputation, and as a result will avoid more risky patients. This is possible because of imperfections in the risk-adjustment mechanism. As a result, physicians are less willing to perform surgery on the most severely ill patients. The result is a misleading inference that mortality declined due to improved quality based on the simple morality trends.

The empirical analysis performed by Dranove and coworkers offers evidence consistent with the hypothesized selection behavior. Controlling for selection, they show a reduction in severity of patient illness accompanied by a spending increase. (It is worth noting that other analyses of the New York experience show that nearly one in five doctors with low performance ratings (bottom quartile) left the practice of cardiac surgery in New York State, which implies an alternative explanation of the observed data (Jha and Epstein 2004).) Dranove et al. (2002) interpret the evidence as pointing to a loss in welfare. To make this interpretation they presume that, prior to the reporting initiative, the sickest patients were being appropriately treated: an assumption not clearly supported by evidence. The analysis therefore asserts a type of reputation-maximizing behavior that dominates concerns about the well-being of the sickest patients. Another interpretation might be that the public reporting of data led physicians to reweight how they use information that comes from sources other than their own or the immediate local experience. This could well generate observations consistent with selection and the observed compression of variance, but might have a less depressing normative conclusion. This might be the case if at baseline physicians were offering CABG to “too many” very sick patients.

One prominent theme in health policy that has only begun to receive careful attention from economists is the issue of disparities in treatment and health-care utilization according to race and ethnicity (Institute of Medicine 2002). Balsa and McGuire (2003) suggest a behavioral approach to modification of the type of model of doctor–patient interactions discussed above. They propose a central role for a stereotyping heuristic that is used by physicians who face important time constraints and must quickly make assessments of complex clinical circumstances. Such a heuristic can offer an efficient method of making uncertain judgments with limited information. It can also result in important errors. Because personal attributes and health habits are typically important for deciding upon a course of treatment, the use of stereotypes might particularly distort clinical choices. For example, physicians have been shown to hold beliefs that African-American patients are more likely to abuse drugs and less likely to comply with recommended treatments than are otherwise similar (with respect to socioeconomic characteristics) white patients (van Ryn and Burke 2000). The fact that physicians hold such beliefs potentially affects the nature of the efforts that physicians take in administering a particular treatment, because judgments about patient compliance, for example, influence expected outcomes.

A second area of application involves the complexity of the medical practice. American doctors practice in an environment where they treat patients associated with a wide range of insurance arrangements, meaning that the patients face different out-of-pocket prices for differing services and doctors are compensated in a variety of ways. For example, a physician will typically encounter fifteen or more different formulary arrangements that define which prescription drugs are paid for and how.13 In addition, they will face similar numbers of compensation schemes, bonus arrangements, quality reporting methods, and patient cost-sharing rules. A recent analysis by Glied and Zivin (2002) shows that physician behavior is not consistent with simple maximization models. They examine physician choices about intensity of treatment as measured by duration of visits, test orders, and medications prescribed. Their results show that physicians respond to incentives but not necessarily to the incentives of the marginal patient. They report that the intensity of treatment received by a given patient has as much to do with the payment incentives associated with other patients in the practice as with their own.14 Similar patients should get similar treatment.15 If physicians have a collectivity orientation (possibly reinforced by professional norms) as proposed by Arrow (1963), then treating patients similarly may have intrinsic value and may constrain how a physician can respond to heterogeneous incentives in payments. Kahneman et al. (1986) explore how notions of fairness constrain profit-maximizing choices. The notion that there are established standards or entitlements that are internalized by physicians and that these influence the supply responses to heterogeneous incentive arrangements constitutes an extension to the ideas of how fairness constrains profit-seeking.16

Another tack that may complement the idea of incorporating fairness into models of physician behavior is that of applying a heuristic in the face of a complex environment in which it is costly to optimize. Fairness in this manner would contribute to the choice of rules of thumb in responding to the daunting array of payment arrangements commonly faced by medical practices (Conlisk 1996).

This chapter has focused primarily on markets for physician services, in part because they serve as an excellent model for a large class of prevalent health sector issues related to the supply and demand for treatment under conditions of asymmetric information and uncertainty. There are also other issues in health economics where traditional models of economic behavior have not resolved some important puzzles and these may lend themselves productively to the application of behavioral economics. I raise several puzzles that relate to demand and health insurance to illustrate the possibilities.

In the discussion of physician behavior, considerable attention was devoted to consumer demand for individual physician services. Here we briefly identify several other issues in the demand for health care where behavioral economics may have a constructive role in aiding the explanation of persistent puzzles. It is commonly observed by health policy analysts concerned with efficiency and quality that there is persistent overuse, underuse and inappropriate use of care (Institute of Medicine 2001). The discussion of physician behavior offered some explanations for what has been termed overuse and inappropriate use of services. The demand-side sources of underuse that are commonly used in the health sector rely primarily on factors such as externalities, as is the case with the demand for vaccines or lack of insurance. The existence of external effects results in inefficiently low levels of demand even when vaccines are made available at a price of zero. The policy response is to install some coercive measures such as requiring childhood immunizations to be documented as a condition of entry into school. Another major source of underuse is the existence of financial obstacles. However, underuse exists in insured populations. In the absence of externalities, understanding the demand side of underuse in the context of a nearly fully insured population is more difficult.

Existing literature on demand for health care offers several directions for studying the issue of underuse of medical care. One line of research incorporates ideas of stigma into the preference function in a fashion that assigns stigma the role of a “price.” Research on the demand for mental health services and treatment for HIV-related disorders are cases in point (McGuire 1981; Frank and McGuire 2000). In these models getting treatment serves to reveal a stigmatizing condition, thereby imposing an additional cost on the patient if they get care. Stigma has been used to explain the low rates of treatment among people with mental disorders (e.g., 27% of people with depression and about 50% of people with schizophrenia).

A new approach to understanding demand behavior draws on research in behavioral economics by Caplin and Leahy (2001). Koszegi (2003) makes use of Caplin and Leahy’s psychological expected utility model, where mental states that affect utility are influenced by both beliefs and observed outcomes.17 Information affects beliefs and in turn the mental states that are related to utility. Koszegi uses this framework to show how anxiety might affect the demand for specific information, tests, and treatment. He identifies a trade-off between seeking treatment and obtaining information. Information, for some patients, can create lost utility from anxiety if the news is bad, but having more complete information enables a patient and their doctor to more optimally choose a treatment strategy. Depending on the net contribution of the information to utility, a patient will demand contact with providers and information about their condition. Not having all the available information can cause anxiety in other patients. Applying models of consumer behavior that incorporate anticipatory feelings into quasi-Bayesian updating models about how medical information and associated physician contacts are used and in turn affect demand for services has the potential to address a range of “underuse” problems such as noncompliance with treatment regimens (Loewenstein 1987).

A third direction for studying demand is suggested by observations made by decision scientists who have attempted to study health utility states. They have noted a rather dramatic ability of people to adapt to changing health states. That is, people who develop significant chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes, strokes, limited mobility) tend to rate their well-being at levels similar to that of the general population. The usual specifications of preferences propose inter-temporal and inter-state stability in preferences.18 These observations suggest a somewhat different process than that studied in hyperbolic discounting (Thaler 1981). Modeling adjustment to health states may contribute to explaining behavior with respect to hospice care, end-of-life care, and the use of advance medical directives.

Unrelated to issues of “under treatment” is a demand-side puzzle that has come to light in recent studies of demand response to different drug formulary designs (see, for example, Huskamp et al. 2004). Those studies estimated demand response to changes in the relative prices, created by implementation of a formulary design change, for different drugs within a therapeutic class (e.g., proton pump inhibitors). Several therapeutic classes were studied. Some classes contained drugs that were found in clinical studies to be highly substitutable in production (they produce comparable clinical benefits and have similar side effect profiles), while others are considered more heterogeneous and less substitutable. Estimated demand responses across classes were generally quite modest and of similar magnitude across therapeutic classes. In particular, the demand response for proton pump inhibitors (a treatment for gastritis) was small, even though studies of the clinical properties of these drugs indicate that they are highly substitutable in production (Wolfe 2003). Moreover, physicians appear to view these drugs as clinically similar. The implication is that consumers are reluctant to change drugs. Why should consumers be unresponsive to substantial relative demand price differences (100%) given the evidence on the high degree of substitution in production?

The parallels between the observations made in the preceding paragraphs and the theoretical and experimental research on reference levels and status quo bias is striking (Knetsch 1989; Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988). It appears that the initial choice of products affects preferences even in the context of low transaction costs and high degrees of similarity in product attributes. This may explain why pharmaceutical promotion relies so heavily on providing free samples that are commonly used by physicians to start a patient on a new drug regimen. Models of demand for prescription drugs might therefore profitably incorporate information on the history of individual product use. Such considerations have been allowed for when empirical studies of demand response examine new prescriptions separately from refills. The normative implications are potentially significant in that evidence of such preference structures would potentially constitute a rationale for the design of formularies that override consumer preferences. Closed formularies, which will only pay for drugs on the list of preferred products, represent one mechanism that would override consumer preferences and cause a shift to a new reference or status quo product.19

One puzzle from the health insurance markets that has received some treatment from behavioral economics is that of why insurance plans with close to first-dollar coverage dominate health insurance markets. Economists have long been concerned with the nature of the trade-off between moral hazard and risk spreading (Zeckhauser 1970). The fact that health insurance markets persistently have equilibrium policies with levels of cost sharing that approximate first-dollar coverage is puzzling in that there appears to be a surprisingly high willingness to pay for the least valuable forms of insurance protection.

Thaler (1980) addressed this issue by appealing to the idea of regret. He argued that insurance features such as deductibles that force consumers to trade-off medical care use for money impose important psychic costs because of the potential for regret. In order to avoid making trade-offs that they might later regret, consumers are posited to demand health insurance designs that allow them to remove themselves from making such choices. The result is an increased willingness of people to pay premiums to obtain first-dollar coverage.

Finally, an issue related to the use of markets to purchase health insurance. A longstanding debate in health policy and health economics involves the trade-off between the efficiency gains from competitive insurance markets and the losses that stem from adverse selection (Cutler and Zeckhauser 2000). The empirical health economics literature offers evidence of both substantial price reductions when competition is intense and large losses from adverse selection (Cutler and Reber 1998). There is a presumption in much of health economics that more choice is better. In fact, the de facto model of health-care delivery in the United States and other nations is that of “managed competition” (Enthoven 1988). The assumption is that consumers find the right health plans and that overall the net gains of wider choice are positive.

At the same time consumers appear to know little about health plans in their choice sets. Recent consumer surveys suggest that only about 36% of consumers believe they understand differences between health plans offered to them (Kaiser Family Foundation 2000). For example, less than 50% of surveyed consumers knew that health maintenance organizations (HMOs) were plans that place greater emphasis on preventive care. In addition, employers that organize markets for health insurance frequently limit the range of consumer choice of health insurance. Nevertheless, U.S. public policy has in recent years encouraged the broadest choices possible in the design of health insurance schemes such as Medicare and the Federal Employees Health Benefit program. Little research has been conducted on the effectiveness of consumer choice in health insurance markets.

General lessons from the behavioral economics literature may lead one to conclude that the analysis of the trade-off from expanding choice among competing health plans may be quite incomplete. Research in behavioral economics shows that, as the number of choices among complicated products expands, consumers appear to consider a decreasing number of the available options, or they attempt to avoid choices altogether by putting off decisions or reverting to a default option (Johnson et al. 1993). It has also been shown that, as decisions become more complex, people adopt increasingly simple rules of thumb to make their choices (Payne et al. 1993). Loewenstein (2000) applies these ideas to the problem of U.S. Social Security reform. He argues that, in that case, the costs of more choice may exceed the benefits. The health insurance market is filled with natural experiments in complex, seemingly high-stakes choices where the choice set varies dramatically. Empirical analysis motivated by the behavioral economics concepts noted here may offer valuable information for better understanding of the net benefits of expanding choice in health insurance.20

For example, the U.S. Medicare program offers a rich laboratory for such investigations. There is a great heterogeneity in the number of managed care plan options available to Medicare beneficiaries across the United States. Yet in all markets there is a common default plan, the traditional fee-for-service Medicare plan. Policy makers and researchers have been repeatedly surprised by the low rates of enrollment in Medicare managed care plans given the richer assortment of insurance coverage they frequently offer (e.g., prescription drugs at no additional premium cost). Understanding how the structure of the choice set affects the willingness to depart from the default option would be important for understanding trade-offs in program design choices. Specifically, are Medicare beneficiaries who face larger numbers of choices more likely to choose traditional Medicare over managed care plans? This would be important information for a U.S. Congress that has shown such a strong interest in encouraging enrollment in managed care arrangements for Medicare beneficiaries.21

The health sector has long offered a challenging venue for applied economists. Arrow recognized this in the early 1960s. Following the tradition of Arrow, I have focused the discussion here on markets for health services and health insurance. Health economists have become habituated to dealing with institutions and facts that raise questions about the usefulness of applying the neoclassical model to health-care markets. The nature of the doctor–patient interaction in the presence of insurance is at the heart of many of the most challenging problems in health policy and health economics. The first empirical studies in health economics came face to face with the issue of characterizing the doctor–patient interaction, and it remains a central problem in health economics. The application of standard principal–agent models has produced an increasingly sophisticated ability to describe doctor–patient interactions and to develop refutable hypotheses about parameters that affect price, quantity, and quality outcomes. Nevertheless, observed demand and supply responses in markets for physician services are incompletely understood. The case of public reporting of physician performance in CABG surgery offers a vivid example of the limited ability of the standard model to explain market behavior.

Behavioral economics offers some concepts and analytical tools that fit well with the institutions of the health sector. The doctor–patient decision-making context of limited information, a noisy health production function, fear, anxiety, insurance coverage, and trust is well suited to the concerns of behavioral economics. I have attempted to highlight how relatively simple models of the doctor–patient interactions can be extended using ideas from behavioral economics to enrich the ability to understand and develop empirical models of health-care markets. The issues identified go to the core concerns of health economics. These include: how information affects equilibrium quality in health-care markets; how physician competition might affect prices and quantities; what produces persistent variations in treatment patterns across markets and the associated welfare losses; and what explains racial and ethnic disparities in health-care use. I have emphasized the role of behavioral economics in extending positive models of health-care markets. Behavioral economics offers direction for addressing long-standing impasses in positive health economics.

There are also important normative implications. Clearly, if doctors and patients make the types of context-specific choices and cognitive errors described here, demand functions can no longer be given the normative interpretations that are common even in health economics (Rice 1998). Critics of the use of standard demand models in health care have clearly and persuasively highlighted the limits to using these for normative model analysis. They have also failed to offer new approaches to understanding such behavior.

One direction pointed to by Thaler and Sunstein (2003) is to use cost–benefit analysis of alternate polices that aim to account for the type of cognitive errors described here. Cost-effectiveness is widely applied in health care to make efficiency judgments about competing medical practices and policies. There are, however, a variety of difficulties in applying these tools in the context of trying to account for consumer preferences for making welfare judgments (Garber 2000).

Another interesting approach is known as case-based decision theory (Gilboa and Schmeidler 2004). In this case the normative analysis is conducted by assessing whether a policy action results in a reduction in the type of decision-making “errors” that serve to undermine the types of expected utility models frequently used in health economics. Thus, policies that reduce distortions in decision-making would be viewed as “welfare-improving.” These are new ideas and to date there is no clear path toward a new normative approach that might be applied in fields such as health economics.

The policy implications stemming from the application of behavioral economics in analyzing health-care markets are potentially profound. Two cornerstones of recent U.S. health policy are the presumption that increasing the availability of information to consumers will result in improved quality of care, and that more choice of health plans and providers will inevitably make consumers better off. Examining the basic laboratory and psychological research used in behavioral economics immediately raises challenges to these policy fundamentals. I have attempted to identify some specific areas where these ideas might have particular importance for ongoing policy debates. I expect that a sustained program of research involving the ideas of behavioral economics applied to health-care markets will likely result in at least some intelligent modification of these articles of faith.

Akerlof, G. 1991. Procrastination and obedience. American Economic Review 81:1–19.

Arrow, K. J. 1963. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. American Economic Review 53:941–73.

Balsa, A. J., and T. G. McGuire. 2003. Prejudice, clinical uncertainty and stereotyping as sources of health disparities. Journal of Health Economics 22:89–116.

Beaver, K., J. B. Bogg, and K. A. Luker. 1999. Decision-making role preferences and information needs: a comparison of colorectal and breast cancer. Health Expectations 2:266–76.

Becker, G. 1964. Human Capital. Columbia University Press.

Becker, G., and K. Murphy. 1988. A theory of rational addiction. Journal of Political Economy 96:675–700.

Ben Sira, Z. 1980. Affective and instrumental components in the physician–patient relationship: an added dimension of interaction theory. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 21:170–80.

Camerer, C. F., and G. Loewenstein. 2003. Behavioral economics: past present and future. In Advances in Behavioral Economics (ed. C. Camerer, G. Loewenstein, and M. Rabin). Princeton University Press.

Caplin, A., and K. Eliaz. 2003. AIDS and psychology: a mechanism design approach. RAND Journal of Economics 34:631–46.

Caplin, A., and J. Leahy. 2001. Psychological expected utility theory and anticipated feelings. Quarterly Journal of Economics 116:55–80.

Chassin, M. R., E. L. Hannan, and B. A. DeBuono. 1996. Benefits and hazards of reporting medical outcomes publicly. New England Journal of Medicine 334:394–98.

Cleary, P. D., and S. Edgman-Levitan. 1997. Health care quality: incorporating consumer perspectives. Journal of the American Medical Association 278:1608–12.

Conlisk, J. 1996. Why bounded rationality? Journal of Economic Literature 34:669–700.

Culyer, A., and J. P. Newhouse. 2000. The Handbook of Health Economics. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Cutler, D. M., and S. J. Reber. 1998. Paying for health insurance: the trade-off between competition and adverse selection. Quarterly Journal of Economics 113:433–66.

Cutler, D. M., and R. Zeckhauser. 2000. The anatomy of health insurance. In The Handbook of Health Economics (ed. A. Culyer and J. P. Newhouse). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Dranove, D. 1988. Demand inducement and the physician/patient relationship. Economic Enquiry 26:281–98.

Dranove, D., and M. Satterthwaite, 1992. Monopolistic competition when price and quality are not perfectly observable. RAND Journal of Economics 23:518–34.

Dranove, D., and W. D. White. 1987. Agency and the organization of health care delivery. Inquiry 24:405–15.

Dranove, D., D. Kessler, M. McClellan, and M. Satterthwaite. 2002. Is more information better? The effects of report cards on health care providers. NBER Working Paper 869.

Edgman-Levitan, S., and P. D. Cleary. 1996. What information do consumers want and need? Health Affairs 15:42–56.

Emons, W. 1997. Credence goods and fraudulent experts. RAND Journal of Economics 28:107–19.

Enthoven, A. C. 1988. The Theory and Practice of Managed Competition in Health Care Finance. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Evans, R. G. 1974. Supplier-induced demand: some empirical evidence and implications. In The Economics of Health and Medical Care (ed. M. Perlman). Wiley.

Feldstein, M. S. 1970. The rising price of physicians’ services. Review of Economics and Statistics 51:121–33.

Frank, R. G., and T. G. McGuire. 2000. Economics and mental health. In Handbook of Health Economics (ed. A. Culyer and J. P. Newhouse). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Frech, H. E., and P. B. Ginsburg. 1972. Physician pricing: monopolistic or competitive comment. Southern Economic Journal 38:573–77.

Fuchs, V. R. 1978. The supply of surgeons and the demand for operations. Journal of Human Resources 13 (supplement):35–55.

Fuchs, V. R., and M. J. Kramer. 1972. Determinants of Expenditures for Physician Services in the United States. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Services Research.

Garber, A. 2000. Advances in cost effectiveness analysis. In Handbook of Health Economics (ed. A. Culyer and J. P. Newhouse). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Gawande, A. 2002. Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science. New York: Picador.

Gilboa, I., and Schmeidler D. 2004. Case-based decision theory. In Advances in Behavioral Economics (ed. C. F. Camerer, G. Loewenstein, and M. Rabin), pp. 659–88. Princeton University Press.

Glaeser, E. L. 2003. Psychology and the market. NBER Working Paper 10203.

Glied, S., and J. G. Zivin. 2002. How do doctors behave when some (but not all) of their patients are in managed care. Journal of Health Economics 21:337–53.

Grossman, M. 1972. On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. Journal of Political Economy 80:223–55.

Gruber, J., and B. Koszegi. 2001. Is addiction rational? Theory and evidence. Quarterly Journal of Economics 116:1261–1303.

Hall, M. A. 2001. Arrow on trust. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 26:1131–44.

Hellerstein, J. K. 1998. The importance of the physician in the generic versus trade-name prescription decision. RAND Journal of Economics 29:108–36.

Huskamp, H. A., R. G. Frank, K. McGuigan, and Y. Zhang. 2004. The demand response to implementation of a three-tiered formulary. Harvard University Working Paper.

Institute of Medicine. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm. Washington, DC: NAS Press.

——. 2002. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: NAS Press.

Jha, A. K., and A. M. Epstein. 2004. The predictive accuracy of the New York State bypass surgery reporting system and its impact on volume and surgical practice. Manuscript, Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard School of Public Health.

Johnson, E. J., J. Hershey, J. Meszaros, and H. Kunreuther. 1993. Framing probability distortions, and insurance decisions. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 7:35–51.

Kahneman, D. 2003. A perspective on judgment and choice: mapping bounded rationality. American Psychologist 58:697–720.

Kahneman, D., J. L. Knetsch, and R. H. Thaler. 1986. Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: entitlements in the market. American Economic Review 76:728–41.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2000. National Survey on Americans as Health Care Consumers: An Update on the Role of Quality Information. Highlights of a National Survey. Rockville, MD: Kaiser Family Foundation, and the Agency for Health-care Research and Quality. (Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/kffhigh00.htm.)

——. 2003. Trends and indicators in a changing health care marketplace. Kaiser Family Foundation publications. (Available at http://www.kff.org/insurance/7031/index.cfm.)

Knetsch, J. 1989. The endowment effect and evidence of non-reversible indifference curves. American Economic Review 79:1277–84.

Koszegi, B. 2003. Health, anxiety and patient behavior. Journal of Health Economics 22: 1073–84.

Loewenstein, G. A. 1987. Anticipation and the valuation of delayed consumption. Economic Journal 97:666–84.

——. 2000. Costs and benefits of health and retirement-related choice. In Social Security and Medicare: Individual vs Collective Risk and Responsibility (ed. S. Burke, E. Kingson, and U. Reinhardt). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

——. 2001. A visceral account of addiction. In Smoking: Risk Perception and Policy (ed. P. Slovic), pp. 188–215. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

McGuire, T. G. 1981. Financing Psychotherapy: Costs, Effects and Public Policy. Cambridge, MA: Ballentine Books.

——. 2000. The economics of physician behavior. In Handbook of Health Economics (ed. A. Culyer and J. P. Newhouse). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Mullainathan, S., and R. H. Thaler. 2001. Behavioral economics. In International Encyclopedia of Social Sciences, 1st edn, pp. 1094–1100. New York: Pergamon.

Newhouse, J. P. 1970. A model of physician pricing. Southern Economics Journal 37:174–83.

——. 2003. Pricing the Priceless. Harvard University Press.

O’Donoghue, T., and M. Rabin. 1999. Addiction and self-control. In Addiction: Entries and Exits (ed. J. Elster), pp. 169–206. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Pauly, M. V. 2001. Kenneth Arrow and the changing economics of health care: foreword. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 26:829–34.

Pauly, M. V., and M. Satterthwaite. 1981. The pricing of primary care physician’s services: a test of the role of consumer information. Bell Journal of Economics 12:488–506.

Payne, J. W., E. J. Johnson, and J. R. Bettman. 1993. The Adaptive Decision Maker. Cambridge University Press.

Phelps, C. E. 2000. Information diffusion and best practice adoption. In Handbook of Health Economics (ed. A. Culyer and J. P. Newhouse). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Phelps, C. E., and C. Mooney. 1993. Variations in medical practice: causes and consequences. In Competitive Approaches to Health Care Reform (ed. R. Arnould, R. Rich, and W. White). Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Rabin, M. 1998. Psychology and economics. Journal of Economic Literature 36:11–46.

——. 2002. Inference by believers in the law of small numbers. Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Rabin, M., and J. Schrag. 1999. First impressions matter: a model of confirmatory bias. Quarterly Journal of Economics 114:37–82.

Reinhardt, U. 1978. Comment on monopolistic elements in the market for physician services. In Competition in the Health Sector (ed. H. Greenberg), pp. 121–48. Aspen, CO: Aspen Press.

Rice, T. 1998. Health Economics Reconsidered. Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press.

Samuelson, W., and R. Zeckhauser. 1988. Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 1:7–59.

Schneider, E. C., and A. M. Epstein. 1998. Use of public performance reports: a survey of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Journal of the American Medical Association 279:1638–42.

Schoenbaum, M. 1997. Do smokers understand the mortality effects of smoking? Evidence from the health and retirement survey. American Journal of Public Health 87:755–59.

Shaller, D., S. Sofaer, S. D. Findlay, J. H. Hibbard, D. Lansky, and S. Delbanco. 2003. Consumers and quality-driven health care: a call to action. Health Affairs 22:95–101.

Simon, H. 1958. Theories of decision making in economics and behavioral science. American Economic Review 49:253–283.

Stano, M. 1987. A further analysis of the physician inducement controversy. Journal of Health Economics 6:229–38.

Thaler, R. H. 1980. Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 1:39–60.

Thaler, R. H., and R. Sunstein. 2003. Libertarian paternalism. American Economic Review 93:175–79.

Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1973. Availability: a heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology 5:207–32.

Van Ryn, M., and J. Burke. 2000. The effect of patient race and socioeconomic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Social Science and Medicine 50:813–28.

Wennberg, J. E., and M. M. Cooper (eds). 1997. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Publishing.

Wolfe, M. W. 2003. Overview and comparison of the proton pump inhibitors for the treatment of acid-related disorders. (Available at http://patients.uptodate.com/topic.asp?file=acidpep/10094.)

Zeckhauser, R. 1970. Medical insurance: a case study in the trade-off between risk spreading and appropriate incentives. Journal of Economic Theory 2:10–26.

There are few, if any, sectors in the economy where the growing paradigm generally termed “behavioral economics” seems to be as relevant and important as the market for health services. Starting with Arrow (1963), many economists have recognized the fact that, in the health services and health insurance market, consumers and providers cannot (on the basis of their behavior) reasonably be described as rational agents acting to maximize their expected utility or profit. Furthermore, motives and considerations such as altruism, trust, and norms, often outside the economists’ usual playground, appear to play an important role in the agents’ decision-making process. Most of these researchers, however, have implemented their own, often ad hoc, assumptions about how agents behave in these markets and very few have actually relied on models developed and results obtained in related behavioral fields such as psychology, sociology, and, especially, the more recently emerging field of behavioral economics. It is perhaps for this reason that, in spite of the voluminous research addressing this issue and the tremendous effort it has involved, many economists feel that we have not yet come up with a good model (or models) for understanding one of the most important activities in health care: the doctor–patient interaction (see McGuire (2000) for a thorough discussion on this issue).