Professionalism, trust and cooperation

Professions and professional work require trust and in various senses are sustained by it (Elston, 2009). A close inspection of trust processes involving professions is thus important not only as a topic of interest in its own right, but moreover because considering what it means to trust can also shed significant light on the very nature of professions, the social contexts which they shape and within which they function. If, as we will argue, trust relations around various professions are shifting and increasingly being called into question, then this implies that the form and function of professions are also in a state of flux – and vice versa. The chapter below interrogates some of these changes, alongside some more enduring features, in exploring various ways of conceptually relating trust to a study of professions and professionals.

An awareness of the salience of trust is clearly apparent within many classic studies of professions. Some of the more critical perspectives depicted clients of professionals as relatively powerless and obligated, whereby ‘on entering the domain of the profession … the citizen is expected to give up all but the most humble rights, to put himself into the hands of the expert and trust his judgement and good intentions’ (Freidson, 1970, p. 355). Trust in such analyses could be characterized by dependency and knowledge asymmetry in the face of hegemonic powers, where trust develops either as unwitting obeisance or as a ‘forced option’ (Greener, 2003; Barbalet, 2009). Meanwhile, more positive accounts emphasized the refinement and specialization of expert knowledge applied by professionals who were bound by fiduciary obligation. The enduring legacy and significance of a profession’s symbolic value thus obliged the professional as much as the client (Parsons, 1975). Professionals were valued, therefore, through their proven ability to manage uncertainty and complexity on our behalf – with trust emerging from quality past experiences, while also underpinning interactions in the present and orientations to the future through binding mutual obligation.

As much as more classical approaches provide many useful starting points for analysing trust, the sociology of the professions has developed greatly since these earlier studies (as described elsewhere in this Companion), and moreover, the nature of trust around professions would appear to have been decidedly altered amidst the intensifying pressures of late-modern societies. This chapter will therefore focus upon more recent theoretical work on trust and professions, delineating five main themes around which the chapter will be structured: (a) the regulatory and organizational apparatus around professional work can usefully be illuminated through notions of abstract systems (Giddens, 1990) and related system-trust (Luhmann, 1979); (b) accordingly, challenges to self-regulation will be explored through the construction of a trust crisis and the contrasting narratives of professionals as self-interested knaves or more benevolent knights (Le Grand, 2010; Dixon-Woods et al., 2011); (c) ostensible changes in levels of system-trust in professionals have led to shifts in the balance between trust and checking within the governance frameworks by which professionals are monitored and held accountable for their work (Davies and Mannion, 1999); (d) at a more micro-level, the nature of professional work relies on the ability of individual professionals to successfully embody the expertise and appropriate motivations which are intrinsic to winning trust (Calnan and Rowe, 2008), whereby interactions with clients may be influenced by changing regulation; and (e) dysfunctional aspects of the regulation and (external) governance of existing mainstream professions can help us understand challenges in effective facework, status and trust building for existing professions, as well as the investment of trust and hope in (re-)emerging professions. We will conclude the chapter by reflecting upon some new formats of professional trust dynamics emerging within late modernity (Kuhlmann, 2006; Brown and Calnan, 2011).

Within the chapter we refer to various cases and country contexts but focus mainly upon the British, and especially the English, medical profession. This choice is partly pragmatic (as the context we know best), but medicine is moreover seen as the archetypal profession in terms of uniquely high levels of trust, power and social influence (Elston, 2009, p. 18), yet it is where high levels of uncertainty and unpredictability make trust more explicit. England also represents an extreme case in the way that new formats of (external) regulation of professionals – not least medical professionals – and the related imposition of new public management (NPM) have been implemented in a particularly swift and stringent manner (Alaszewski, 2002; Moran, 2003; Dixon-Woods et al., 2011). As we will explore in the first main section, trust, power and societal influence are vitally bound up with the nature of regulation and pressures towards change.

Regulation as a basis for system-trust

Systems of regulation: building trust through inclusion and exclusion

One of the key defining attributes of a profession, structures of (self-)regulation have changed dramatically over many centuries and are significant for understanding the power, status and general esteem of particular professions across wider society (Freidson, 1970). Moran (2003, p. 42) describes how in Britain the ‘ancient professions’ of clerics, lawyers and doctors came to be regulated via more formal and legal mechanisms following a series of reforms across the middle part of the nineteenth century. Yet while the British Apothecaries Act (1815), as with the Dutch Regulation of Medical Practice Act (1865 – Wet regelende de uitoefening der geneeskunst) and other laws across Europe, created much more formal legal delineations between professionals and outsiders, within the profession itself self-regulation remained relatively informal, ‘cooperative’ and ‘light touch’ (Moran, 2003, p. 42).

These nineteenth-century reforms of the ancient professions and creation of many new professions involved the instituting of a great many organizations that would go on to hold important symbolic value for how various professions have come to be viewed across wider societies. Perhaps most visible of all professions (Elston, 2009), the clear legal parameters regarding doctors’ training and registration – especially the placing of these under peer scrutiny – helped to generate a sense of appropriate checks and balances which has laid the taken-for-granted basis of patients’ interactions with medical professionals (Giddens, 1990).

The institution of the General Medical Council (GMC) (as it is now known) through the 1858 Medical Act can thus be seen as pivotal to the development of the ‘modern’ profession of medicine in Britain. The wider legislation and the GMC itself were partly the product of reformist political pressures, epitomized by the campaigning of Thomas Wakeley and The Lancet which he founded and edited. Railing against both the elitism of the medical establishment and the prevalence of ‘quackery’ in common approaches to disease, the reformists campaigned for a more meritocratic and scientifically trained medical profession (Burney, 2007). For Wakeley, the need for a more (meritocratic, non-elitist) inclusive yet (anti-quackery) exclusive profession went hand-in-hand:

By excluding the medical rank and file from full membership, the [elitist] royal colleges demeaned the majority of medical practitioners before their public, implying that their qualifications were not sufficient to distinguish them from those practicing without a licence.

(Burney, 2007, p. 56)

This quotation, written regarding a historical moment which was crucial to the forging of the modern medical profession, points to a number of important social dynamics around professions which are salient for our concerns regarding trust. First, the societal view of how a profession functions at an organizational level has important implications for how individual practitioners or groups of practitioners are perceived. Second, such a colouring of views of professionals often remains more implicit than explicit. Yet nevertheless, and third, changes to the central legal-organizational structures and functioning of a profession have important implications for members and non-members and how they are viewed by ‘their public’.

Interpersonal trust interacting with system-trust

In further analysing the first of these three concerns, it is useful to consider interpersonal trust, placed in individual professionals, alongside broader views of a profession as an abstract system of expert knowledge (Luhmann, 1988; Giddens, 1990). Interpersonal trust has been defined as ‘the optimistic acceptance of a vulnerable situation in which the truster believes the trustee will care for the truster’s interests’ (Hall et al., 2001, p. 615). In accounting for such acceptance, Luhmann (1988, pp. 95–96) encourages us to think about the ways in which we make assumptions based upon what is familiar or, moreover, how we start to make sense of contexts which are unfamiliar. In both types of setting, we might navigate uncertainty by implicit reference to the symbolic meanings we associate with social actors and their actions, in relation to wider social systems (Luhmann, 1988; Möllering, 2005). Alternatively, in some other settings, we abstractly consider or assume the functioning of systems as a proxy for the actions of many individual professionals – in the absence of direct encounters with these professionals (Luhmann, 1988).

Whether we are trusting in a (familiar) family doctor with the drug she is asking us to ingest (but which could harm us), or whether we are ‘trusting’ in the system of aircraft maintenance which seeks to render our pending flight a safe one (but which could fall out of the sky), we adopt an ‘attitude’ which overlooks risk through a ‘previous structural reduction in complexity’ (Luhmann, 1988, p. 103). Our more or less precise understandings and/or assumptions regarding social systems of professional expertise, training in this expertise and the ongoing regulation of practice – in line with the state of the art – help us rule out large swathes of complexity such as those regarding the family doctor knowing nothing about that medicine or the aircraft engineers casting nothing more than a cursory glance at a plane before granting permission to fly. When heeding the doctor or while boarding the plane we take these and other basic premises for granted. Luhmann (1988) calls this confidence, facilitated through systems.

There are, of course, important differences between the two cases above. The interaction with a specific individual doctor may be underpinned by certain assumptions regarding the abstract system of the medical profession, but it also involves interaction dynamics and a relational proximity through which we develop further understandings of this professional’s competence, but also of her motives and the compatibility of these with our own goals and concerns (Brown, 2008, p. 351). This interaction between a professional and patient can be seen as taking place at an ‘access point’ into the abstract system – ‘the meeting ground of facework and faceless commitments’ (Giddens, 1990, p. 83), where these facework commitments exist as more relational and interactive (rather than more abstract or symbolic) bases of trust (p. 80). Ideally, the competence of the medical expert is embodied in the caring professional.

While our experiences at access points are rooted in knowledge of abstract systems and a host of related assumptions regarding the medical profession, healthcare system and local organizational dynamics – with these forming the basis of an interpersonal (dis-)trust – so do our experiences at access points come to shape our generalized views of the abstract system (Giddens, 1990; Brown and Calnan, 2012). Broader, more or less positive, views of professional abstract systems are described by Luhmann (1979) as ‘system-trust’, which by way of its non-specific, non-interpersonal dynamics is qualitatively different to interpersonal trust. Both Luhmann (1988) and Giddens (1990) argue that everyday life in late modernity is characterized by an increased reliance upon such systems, implicitly involving the work of faceless expertise such as our example involving aircraft engineers. Whereas interpersonal trust is built on views of specific professionals’ competence and care in light of system-trust, experiences of reliance on professionals which are wholly devoid of interaction with these professionals are purely based on ‘function’ (Jalava, 2006, p. 25): ‘Such system trust is automatically built up through continual, affirmative experience … it needs constant feedback’ (Luhmann, 1979, p. 50).

Trust, power and maintaining a monopoly of knowledge: challenges to self-regulation

A shift from confidence to trust

In seeking to assure continual affirmative experiences with professionals, regulation of professional work would seem vital for system-trust in professions. Luhmann’s description of system-trust requiring ongoing positive feedback suggests that a profession’s status and esteem within a society are somewhat more precarious than the coercive and monopolistic depictions of some classic texts. If a profession’s status is significantly dependent upon system-trust then, according to some of Luhmann’s (1988) arguments, it may only be as good as the last medicine prescription written by one of its members or the last plane granted permission to fly.

System-trust may be especially prone to lapses in a highly mediatized environment where the public’s likelihood of hearing about failings is made more likely by the willingness of news media to report negative stories and the experiential immediacy of more distant dysfunctions through mediated knowledge flows (Butler and Drakeford, 2005; Warner, 2015). Failings, such as harm from medical treatment, deaths of neglected children or plane crashes, can certainly dent views of a wider profession (Warner, 2015), but Luhmann (1988, p. 104) goes on to qualify that system-trust may be protected, despite dysfunctions, through compelling performances of individual professionals when engaging with clients at access points. Positive first-hand experiences with healthcare professionals may incline patients to explain away failings as one-off aberrations (Brown and Calnan, 2012; Solbjør et al., 2012). Even amidst more regular failings, we may continue to enact trust on the basis that our doctor or our preferred airline (even though we never meet their engineers) possesses special qualities (Luhmann, 1988), regardless of problems elsewhere (Brown, 2009).

Where views of a profession as a whole are importantly shaped by ongoing encounters at access points, coupled to more enduring symbolic significance (Luhmann, 1988), then the more or less successful way expertise is embodied through a professional’s presentation-of-self is fundamental to trusting (as will be considered in a later section). The concreteness of the experiential knowledge derived from direct encounters with professionals, compared with more remote media accounts, explains the relative importance of the former for trust (Brown, 2009). In the case of medical professionals in England, system-trust in professionals remained steadfastly high despite a spate of highly publicized professional failings during the mid to late 1990s, where a family doctor killed many of his patients (Harold Shipman) and where surgeons operating on infants were found to have been undertaking overly risky operations, with mortality rates unusually high as a consequence (Bristol Royal Infirmary). These were merely the two most high-profile incidents amongst many others, yet survey research suggested the percentage of the British public reporting trust in doctors remained very high at close to 90 per cent, even rising the year after Shipman’s conviction for multiple murders (MORI, 2004).

While such survey research may be criticized for its reliability in measuring trust (this survey, for example, focused on professionals’ ‘veracity’), qualitative research in England involving cervical cancer patients receiving treatment in a local area where related services had suffered a number of high-profile problems also found high levels of trust in medical professionals, despite concerns about the healthcare system (Brown, 2009; see also Kuhlmann, 2006). Similarly, in Norway, Solbjør and colleagues (2012) found that patients who developed breast cancer which had not been picked up within (sometimes recent) screening often continued to trust, emphasizing the quality of care they had received, the success of the overall screening programme and explaining away their situation as an exception. Taken together, these quantitative and qualitative findings appear to counter broader discussions about a decline of trust in scientific and professional expertise (c.f. Furedi, 1997).

One way of working through this tension is to distinguish between professionals and healthcare systems, with the former being trusted more than the faceless latter. Another approach would be to return to Luhmann’s conceptual distinction between confidence and trust. We noted earlier that confidence relates to taken-for-granted assumptions about an outcome, one where doubt is not experienced. Luhmann (1988) contrasts this with trust, which involves an awareness of alternative outcomes, doubt and the possibility for regret. Arguably, the professional failings reported above, alongside a more general awareness of the limitations of expertise and fallibility of experts in late modernity, have shifted patients from a position of relative confidence to one of trust, but this is qualitatively different from saying doctors are trusted less than they were (Brown, 2008). This important distinction is implicit elsewhere in the trust literature, for example in denoting a shift along a spectrum from a more blind non-reflexive trust towards more conditional-critical trust (Poortinga and Pidgeon, 2003; Calnan and Rowe, 2008), as we explore below.

The politicization of ‘lost trust’

If trust in some professions has remained high while becoming more critical, it nevertheless entails a change in power dynamics around these professions and professionals’ work (Dent, 2006). At the micro-level, shifts towards more critical forms of trust render different power dynamics in professional–client encounters – whereby the professional is more likely to be questioned, confronted with client perspectives and expert knowledge gathered by the client, and to be required to include the clients’ concerns within any decision-making or advice-giving (Dent, 2006; Buetow et al., 2009). While it is important not to exaggerate such changes and to acknowledge the extent to which more critical-conditional professional–client interactions may be dependent on the cultural capital and educational background of the client, the general direction of changes does indicate a reducing (albeit still strong) power-asymmetry and knowledge monopoly (Brown et al. 2015).

At the more meso-organizational level, that of professional regulation, the impact of changes in trust has arguably been more profound (Moran, 2003; Power, 2004; Dixon-Woods et al., 2011). For while we suggested above that trust in British medical professionals had changed but not necessarily declined, the political machinations around the failings in professional practice provided a very different emphasis. Alaszewski (2002) argues that although dysfunctions in care such as those that took place at Bristol Royal Infirmary in England were not new, the failings nevertheless attracted significant media attention and were successfully politicized and ‘used by the incoming [1997] Labour Government as evidence of the failure of public services and justification of its programme of modernization’ (Alaszewski, 2002, p. 375).

At this broader level of analysis, the position and esteem of a profession has to be analysed in relation to both its public (client-base) and the state which enacts and maintains the legal framework by which, as we saw in the preceding section, the profession’s monopoly of practice is maintained (Moran, 2003; Dent, 2006). A historical perspective on professions notes periods of relatively stable settlements involving these three groups, as well as other moments when these triangular ‘compacts’ break down – resulting in regulatory change (Ham and Alberti, 2002; Moran, 2003). In describing the position of the medical profession before the latter years of the twentieth century, Waring and colleagues follow Salter in denoting:

a triangular regulatory ‘bargain’ that, in its ideal type, provided benefits to civil society through offering some assurance as to the standards of healthcare, benefits to the state in the form of enhanced legitimacy from civil society, and benefits to the profession in the form of trust and the privilege of self-regulation. Its practical effect was that the medical profession was allowed to monitor the conduct and performance of members, for the most part free of external scrutiny.

(Waring et al., 2010, p. 542)

Regardless of what the British public really thought, the successful characterization of the medical profession as having lost public trust (MORI, 2004) was used by successive governments to rework this ‘bargain’, chiefly through a reduced autonomy of the profession – undermining self-regulation, significantly reforming the GMC, requiring revalidation and imposing increasing levels of external governance (Dixon-Woods et al., 2011). Far from mere passive acceptance, elite representatives of the profession were very much involved in such restructuring, echoing and thus legitimizing notions of lost trust.

Trust, checking and control: transaction costs and inter-professional knowledge exchange

Shifts towards new forms of regulation and trust

Where professional organizations fail to successfully regulate the work of their members, to the extent that their publics become harmed, then prima facie there is a case for further intervention by the state. Or, where a professional group has come to depend on the state for much of its employment, then the state may increase its oversight of such professional work to ensure effective use of taxpayers’ money. These were some of the underlying arguments behind a wave of reforms enacted in Britain over the past twenty years, especially between 1997 and 2002, which has been characterized by Moran (2003) as a period of unusually speedy and expansive regulatory reform. In contrast to the very gradual change whereby, for example, teaching had grown increasingly independent of state interference during the first half of the twentieth century, the last decade of the millennium was characterized by a paradigm shift towards a new format of regulatory politics in Britain, with manifold changes across many professions (Moran, 2003).

Le Grand (2010, p. 56) argues that the political organization of education systems or healthcare services is based around certain underlying perceptions and assumptions regarding the respective professionals involved: ‘that is, the extent to which they are “knaves,” motivated primarily by self-interest, or “knights,” motivated by altruism and the desire to provide a public service’. As professionals have been increasingly construed as prone to mishaps and failures to act in the public or client interest, so have they also been depicted as knavish – in keeping with the narrow rational-choice models which dominate much recent policy-making logic (Taylor-Gooby, 2006). In turn, these views have underpinned various new forms of regulation which have emerged in place of the traditional compacts which had their roots in the informal ‘club government’ approach to regulation of the nineteenth century (Moran, 2003).

It is not new to perceive professionals as self-interested – Aneurin Bevan, a founding father of the British National Health Service (NHS) in the 1940s, famously referred to having to ‘stuff [doctors’] mouths with gold’ (Thomas-Symonds, 2010, p. 161) to ensure their cooperation – but the recent intensification of this more instrumental manner of overseeing professions has led to profound changes in their regulation and, accordingly, in the nature of professional work. Common emerging features of this new regulation, in Britain and elsewhere, are the result of ‘complex bargains’, usually involving the acceptance or imposition of some form of external oversight, with certain levels of autonomy retained in return for requiring professionals to work with more encoded forms of knowledge and guidelines of practice (Moran, 2003, p. 81). Moran draws out further common features of the legal and medical professions’ experiences in terms of a much tighter and interwoven relationship between (self-)regulatory organizations and the state (p. 85).

In considering the effects of this more formal, external and imposed regulation, the medical profession in Britain again represents a prototypical case where doctors’ work has been redefined in many ways by the expansion of governance and audit (Flynn, 2002; Harrison and Smith, 2003; Brown, 2011). Clinical governance, a variant of NPM, has combined a proliferation of guidelines and targets with the increased recording and ‘checking’ of professionals’ compliance. ‘Softer’ forms of governance have also been described (Sheaff and Pilgrim, 2006) that impact on knowledge-work in medicine and other professions. Here, we concentrate on a number of implications of these forms of professional oversight for trust.

The impact of new forms of governance on trust and professional work

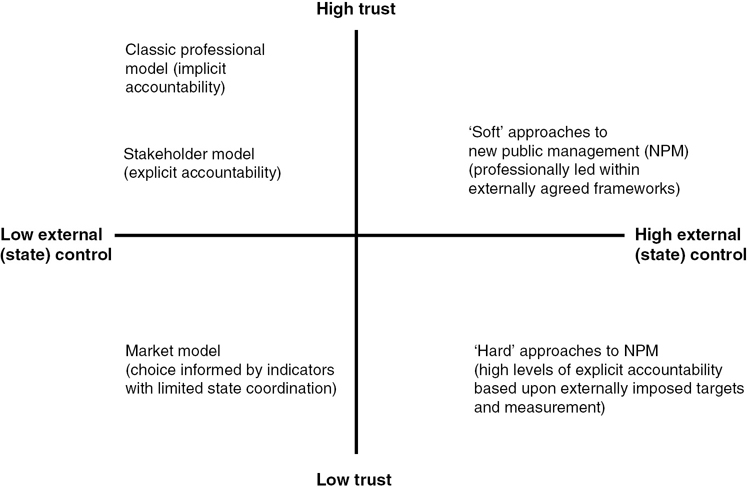

The impact of external governance and NPM reforms can be usefully conceptualized from the perspective of transaction cost economics, whereby transactions of goods, services and knowledge can be managed through markets incentivized via price, bureaucratic stipulations incentivized by hierarchy, or trust incentivized through social norms (Adler, 2001). These three bases of transactions are ideal-types and various combinations of these approaches will be interwoven across any organizational–professional context. Professional work has always been structured around hierarchy and financial contracts to some degree, but the move away from more informal forms of self-regulation within various configurations of NPM certainly represents a diminished role for trust (see Figure 9.1).

Source: adapted from Rowe and Calnan (2006, p. 381).

The shift towards a reliance upon guidelines, audit and checking not only implies a reduced trust in professionals but has been further criticized as positively undermining trust within the organizations in which professionals operate. Davies and Mannion (1999, p. 6) emphasize that while other ways of managing organizational transactions exist, the effective functioning of bureaucratic or market-oriented alternatives to trust are nevertheless ‘underpinned’ by ‘softer information and informal relationships’ grounded in trust. The way in which new forms of auditing professional work may undermine traditional normative-fiduciary structures and related informal commitments is therefore a concern. Where forms of audit are implemented by those outside the profession, who are perceived as not understanding the nuances and intricacies of professional work, then various forms of instrumental and subversive actions may result, from gaming to fabrication of recorded data to selective appropriation of guidelines (Bevan and Hood, 2006; Brown, 2011; Spyridonidis and Calnan, 2011).

Such deleterious effects of new forms of external regulation, through a neglect of trust, would be problematic for any organizational or working context but may be especially dysfunctional for much professional work which is innately ‘knowledge intensive’ (Adler, 2001, p. 216). Trust has been argued to drive efficiencies and quality outcomes in its enabling of informal knowledge exchange, refinement of practices and other key features of organizational learning (Davies and Mannion, 1999; Sheaff and Pilgrim, 2006). Forms of hierarchy and market are not inherently undermining of trust, but the variants of quasi-markets and related forms of regulatory bureaucracy which have emerged within many northern European welfare states and educational systems have resulted in forms of audit-checking which are often described as creating organizational dynamics which distract from the first-order goals of effective professional work (Rothstein, 2006) and usher in “tyrannous” tendencies (Strathern, 2000; Bevan and Hood, 2006), thus undermining quality and efficiency.

Facework and abstract systems: embodying trustworthy practice at access points

Regulatory (mis)trust impacting upon clients’ (mis)trust

The preceding section noted that a perceived need to recast formats of professional regulation, based on doubts around the competence and motives of professionals, has ushered in new forms of governance which have been critiqued for impeding quality professional work but moreover for fostering ‘knavish’ motives rather than overcoming these: ‘a system that does not trust people begets people that cannot be trusted’ (Davies and Lampel, 1998 – quoted in Davies and Mannion, 1999, p. 15). Professionals acting in a more purposive-rational manner are less likely to win the trust of their colleagues, and hence new regulatory systems founded on the premise of limited trust undermine the functioning of this valuable organizational lubricant.

Stimulating more instrumental tendencies within professional work may be problematic for building trust with clients. Earlier in this chapter we briefly addressed the importance of facework for generating interpersonal trust in a particular professional, as well as for galvanizing system-trust in the broader profession. It is possible to identify a number of ways in which new forms of governance may hinder professionals’ trust-building facework, though of course the nature of this facework will vary greatly across different professions and cultural settings.

Effective presentation-of-self within client encounters may be especially crucial for professionals working within health and social care contexts, not least due to the way their emotional labour, embodied interactions and hands-on care-work may provide a rather intense form of experiential knowledge, as drawn upon by the client when inferring the clinical competencies and/or caring qualities of the professional (Brown, 2008). Where the demands placed upon professionals to account for their work create a substantial bureaucratic burden, this may detract from the time which professionals have to engage in facework and trust-building activities (Brown and Calnan, 2012). Trust may still be generated ‘swiftly’ by skilled communicators within certain contexts, especially when certain positive starting assumptions already exist about the professional, though more time may be necessary if trust is to move beyond more calculative and superficial forms towards those based upon mutual knowledge and commitment (Dibben and Lean, 2003, p. 243). These latter deeper forms of trust relations may be very important in facilitating the knowledge exchange and cooperation between client and professional which generate quality outcomes and perpetuate trust over the longer term.

Professional–client interactions impeded by governance

There are further ways in which less-trusting governance systems may impact on professional–client trust. In our research into trust within mental health services, we found that the various professionals involved (psychiatrists, nurses, social workers) experienced high levels of uncertainty in their day-to-day work – not least regarding the diagnostic processes, notions of good care and the management of risk – which were far from straightforward in contexts of psychosis care (Brown and Calnan, 2012). Tensions emerging between the uncertainty which was so characteristic of professionals’ work, on the one hand, and the bureaucratic demands for calculability and control within governance arrangements, on the other, led to many professionals describing heightened experiences of pressure and work-stress (Brown and Calnan, 2012). Stress appeared to vary in relation to level of seniority (senior psychiatrists had greater decision latitude which insulated them from stress) as well as the extent of trust demonstrated by middle managers. Where more junior professionals experienced pressurized work within more low-trust contexts, high levels of absences due to illness (primarily work-stress) were reported. Such effects could, in turn, be seen to affect the quality of care, consistency and time that professional teams were able to provide for clients.

Amidst such pressurized work environments, professionals’ defensive practice may also change the very nature of their work, with a wariness of blame coming to warp the ends and means of professional practice (Power, 2003; Bevan and Hood, 2006; Brown and Calnan, 2012). In various contexts, clients may come to see governance frameworks, not least those pertaining to risk, as driving professionals’ agendas ahead of their own expressed interests (Power, 2004; Rothstein, 2006). This compromising of motives which precludes putting clients first – as inferred from access-point encounters – may lead to negative views of these professionals and, correspondingly, of the profession more broadly (Brown and Calnan, 2012).

Alongside the influence of new forms of regulation and governance, there are also broader societal changes which can be seen as creating challenging dynamics for the maintenance of trust within professional–client interactions. We have already noted how demands for calculability and control from professionals, which have been described as intensifying through cultural developments within modernity, may place professionals working with uncertainty under pressure. These demands may be especially difficult to negotiate as their emergence coincides with a growing awareness of the uncertainty present within abstract systems of knowledge and the fallibility of the professionals who apply this knowledge (Giddens, 1990).

Amidst these shifting features of late modernity, professionals’ presentation or veiling of uncertainty within the encounter may come to bear decisively upon trust dynamics:

There is no skill so carefully honed and no form of expert knowledge so comprehensive that elements of hazard or luck do not come into play. Experts ordinarily presume that lay individuals will feel more reassured if they are not able to observe how frequently these elements enter into expert performance.

(Giddens, 1990, p. 86)

Yet the masking of back-stage uncertainty by front-stage presentation has its limitations. Referring to the actions of family doctors, Fugelli (2001, p. 577) warns that where ‘patients experience too large a difference between “front stage medicine” and “back stage medicine”, trust is lost’.

Trust in (re-)emerging professions

Challenges to mainstream professions amidst a more critical public sphere

In earlier sections we suggested that historic shifts in regulatory structure can be seen as enabling a more homogeneously trusted profession, while concurrently distancing these professionals from non-professionals in the eyes of their publics (Burney, 2007). Establishing the trust of a public is thus one vital source of power for a profession; but so is discrediting outsiders. Much of the politics in the mid-nineteenth-century consolidation of medical professions across various national contexts involved scathing critiques of quackery, which professionals defined themselves against (Burney, 2007). Indeed, organizations such as the Association Against Quackery (Vereniging Tegen de Kwakzalverij) in the Netherlands remain outspoken critics of various complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) techniques within contemporary national public spheres. Undermining trust and hope in CAM is an important feature of this critical discourse (VtdK, 2010, p. 1).

This particular organization also lobbies the Dutch Ministry of Public Health and insurance providers regarding what should and should not be included within basic healthcare insurance coverage for Dutch citizens. The challenging of various ‘alternative’ treatments is seemingly effective, for example in recent laws in the Netherlands prohibiting claims for effectiveness on packaging of homeopathic treatments (Rijksoverheid, 2012, Art.73, para.2) and the recent limiting of tax dispensations to mainstream ‘protected professions’, excluding most CAM practitioners (Rijksoverheid, 2013). These and other recent policy developments elsewhere ward against narratives regarding the inexorable rise of CAM in recent years.

Yet anti-quackery claims become harder to substantiate within late-modern public spheres, where the multiplicity of scientific theories is commonly recognized, where an emphasis on evidence-based medicine is drawing attention to many interventions commonly used in ‘mainstream’ medicine which are evidence-deficient or where contrasting evidence of (non-)effectiveness exists (e.g. Kirsch et al., 2008), and where a few CAM practices are becoming more professionalized and appealing to evidence-based reasoning (Broom and Tovey, 2008; Gale, 2014). This has led some researchers to suggest a shift away from (bio-)medical hegemony-monopoly towards a reversion to medical pluralism (Cant and Sharma, 2004), even if this cannot be seen as a straightforward unidirectional process.

Micro-dynamics in professional–client interactions: new professions winning trust through facework

Amidst these broader macro-level conditions, which render neat distinctions between system-trust in professions and system-distrust in certain outsiders harder to maintain, there exists an array of conditions at the micro-level which further assist the (re-)emergence of some former outsiders towards gradual professionalization. As addressed in the preceding section, the increasing employment of professionals within health, welfare and other state-run institutions and the later influence of various management and efficiency drives have compromised these mainstream professionals’ interactions and, correspondingly, their relationships with their clients.

Mechanic (2001) argues that despite doctors’ concerns to the contrary, average time spent with a patient in primary care consultations increased rather than decreased between the mid 1960s and the mid 1990s. However, this measure of ‘objective’ time does not take into account the increasingly negotiated rather than deferential nature of these encounters, so the subjective ‘cadence’ of these interactions may indeed be less satisfactory for patients and professionals alike. In contrast to the stipulated nine-minute consultations which English patients may expect with their family doctors (Mechanic, 2001), clients of CAM practitioners refer to the extent and cadence of time as one of many features which underlie their usage of these services (Siahpush, 2000). Gale summarizes Siahpush’s (2000) review of reasons for the growing popularity of CAM as including ‘dissatisfaction with the health outcomes of orthodox medicine; dissatisfaction with the medical encounter/doctor–patient relationship; preference for the way alternative therapists treated their patients, including being caring, individualized attention, ample time and information’ (Gale, 2014, p. 807), as well as noting a preference for natural solutions, and the role of some CAM approaches in assisting sense-making amidst illness and death after the decline of organized religion. Although not mentioned explicitly in this list, processes pertaining to trust are very much implicit. As Siahpush (2000, p. 167) states, CAM practitioners are able to be far more patient-oriented in the way they may ‘pay close to attention to trivial symptoms, spend a lot of time with patients and therefore gain their trust and patronization’.

The quality of interpersonal trust building may, very gradually, be furnishing an emerging system-trust which accompanies – drawing upon while helping facilitate – a creeping professionalization in some CAM fields in Britain. Broom and Tovey’s research into patients’ use of CAM in the often staunchly biomedical context of oncology care describes patients’ preferences for the depth and holism of various CAM encounters which

were valued, primarily, for their subjectified (rather than abstracted) and individualized (rather than depersonalized) approach to cancer care; an approach which was seen to allow for, and promote, agency, self-determinism and ultimately hope.

(2008, p. 43)

The extent to which CAM is integrated within British oncology care varies a lot across different institutional and professional settings (Broom and Tovey, 2008), again emphasising the micro and structural dynamics of syncretism-pluralism across professional domains. Gale (2014) similarly points to some broader variations in CAM use which are highly relevant to studies of trust in (new) professions more broadly. In the United States, the increased propensity towards CAM usage amongst African-Americans who have been victims of discrimination, and/or the influence of social network ‘membership’ (Gale, 2014, p. 808), are two examples which underline the salience of a more nuanced and textured attentiveness to different publics and contrasting attitudes towards different professions.

Effects of wider social membership and/or marginalization may be important therefore in noting varying levels of trust in some professions and distrust in others. Distrust amongst certain marginalized groups towards hegemonic professions – which clients are compelled to use despite misgivings in doing so – helps us understand the darker side of professional monopolies, the difficulties faced in professional work and, in extreme situations, the violence and hostility experienced by some professionals more than others (Elston and Gabe, 2008; Newburn, 2014). These nuances underline the limitations of accounts of homogeneous national system-trust in professions, with Hohl and colleagues’ (2013) research into variations in views of the police profession being one useful example.

Nuanced variations in system-trust towards professionals represent a challenge to neat analyses of professions’ status and the structure of professional–client relations. They also pose a challenge to professionals themselves – in the requirement to gauge a client’s attitudes and expectations and respond appropriately. Some clients will expect a more egalitarian, negotiated approach where back-stage issues of evidence and uncertainty are openly worked through when informing clients’ choices. Others will neither expect nor appreciate such interactions, preferring more traditional, professional-driven encounters. The ability of the professional to accurately ‘read’ the client and deliver the appropriate level of (in-)formality, complexity and choice may be increasingly important.

Meanwhile, clients may be more attuned to the varying quality of professionals, with alternative sources of expert information and/or ‘visible markers’ such as league tables being used to negotiate trust amidst a heightened awareness of uncertainty (Greener, 2003; Kuhlmann, 2006). Assessments of the presentation-of-self nevertheless remain vital to the development of (dis-)trust in specific professionals. To the extent that clients adopt this newer more critical-conditional approach, trust in professionals necessitates more active and continual maintenance than in the past (Giddens 1990). Such trust dynamics epitomize a rather different regulatory environment which in some senses may more effectively ensure the quality of individual professional work than earlier forms of a less conditional, more enduring and blanket trust (Brown and Calnan, 2011).

As far as they are able to capture what matters, visible markers of performance applied within new governance frameworks may be useful in generating conditional trust (Kuhlmann, 2006). However, we have noted various perverse tendencies which warp the meaning of these markers and professional practices as a result. Where governance frameworks and markers are developed by professionals themselves, then their enhanced sensitivity to the subtleties of professional work and, correspondingly, their legitimacy amongst professionals, may render them highly effective in facilitating both trust and professional work which merits this trust (Kuhlmann, 2006; Brown and Calnan, 2011). But these processes may only function effectively in the absence of the more instrumental ‘checking’ which otherwise undermines the socio-normative fabric through which trust functions in “civilizing” practice (Brown and Calnan, 2011).

As professional work is increasingly performed within ‘audit societies’, the civilizing influence of trust upon professionals may be increasingly inhibited. Ironically, obstructions to effective trust relations are partly motivated (or at least justified) by ostensible crises of trust. By exploring shifting trust dynamics in the archetypal profession of medicine (Elston, 2009), especially within a national context where trust has been especially problematized and NPM ‘solutions’ fervently pursued, our analysis has sought to provide insights with much broader cross-professional relevance.

Amidst organizational contexts seen as becoming more faceless and bureaucratically and technologically mediated, the value of individual professional faces may be less obvious. Yet we must remember that ‘to ask why societies incorporate their knowledge in professions is thus not only to ask why societies have specialized lifetime experts, but to ask why they place expertise in people rather than things or rules’ (Abbott, 1988, p. 323). Professionals were initially trusted to deal with complexity and, while trusting these professionals has itself become more complex, both these forms of complexity are most satisfactorily resolved by interacting individuals.

References

Abbott, A. (1988) The System of Professions: An Essay on the Division of Expert Labour. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Adler, P. (2001) ‘Market, hierarchy and trust: The knowledge economy and the future of capitalism’. Organization Science, 12(2), pp. 215–234.

Alaszewski, A. (2002) ‘The impact of the Bristol Royal Infirmary disaster and inquiry on public services in the UK’. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 16(4), pp. 371–378.

Barbalet, J. (2009) ‘A characterisation of trust and its consequences’. Theory and Society, 38(4), pp. 367–382.

Bevan, H. and Hood, C. (2006) ‘What’s measured is what matters: Targets and gaming in the English public health care system’. Public Administration, 84(3), pp. 517–538.

Broom, A. and Tovey, P. (2008) Therapeutic Pluralism: Exploring Experiences of Cancer Patients and Professionals. London: Routledge.

Brown, P. (2008) ‘Trusting in the new NHS: Instrumental versus communicative action’. Sociology of Health & Illness, 30(3), pp. 349–363.

Brown, P. (2009) ‘The phenomenology of trust: A Schutzian analysis of the social construction of knowledge by gynae-oncology patients’. Health, Risk and Society, 11(5), pp. 391–407.

Brown, P. (2011) ‘The concept of lifeworld as a tool in analysing health-care work: Exploring professionals’ resistance to governance through subjectivity, norms and experiential knowledge’. Social Theory and Health, 9(2), pp. 147–165.

Brown, P. and Calnan, M. (2011) ‘The civilising processes of trust: Developing quality mechanisms which are local, professional-led and thus legitimate’. Social Policy &Administration, 45(1), pp. 19–34.

Brown, P. and Calnan, M. (2012) Trusting on the Edge: Managing Uncertainty and Vulnerability in the Context of Severe Mental Health Problems. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Brown, P., Elston, ME. and Gabe, J. (2015) From patient deference towards negotiated and precarious informality: An Eliasian analysis of English general practitioners’ understandings of changing patient relations. Social Science & Medicine 146:164–172.

Buetow, S., Jutel, A. and Hoare, K. (2009) ‘Shrinking social space in the doctor–modern patient relationship: A review of forces for, and implications of, homologisation’. Patient Education and Counselling, 74(1), pp. 97–103.

Burney, I. (2007) ‘The politics of particularism: Medicalization and medical reform in 19th century Britain’. In R. Bivins and J. Pickstone (eds) Medicine, Madness and Social History: Essays in Honour of Roy Porter, pp. 46–57. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

Butler, I. and Drakeford, M. (2005) Scandal, Social Policy and Social Welfare. Bristol, UK: Polity Press.

Calnan, M. and Rowe, R. (2008) Trust Matters in Healthcare. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

Cant, S. and Sharma, U. (2004) A New Medical Pluralism: Complementary Medicine, Doctors and the State. London: Taylor & Francis.

Davies, H. and Lampel, J. (1998) ‘Trust in performance indicators’. BMJ Quality and Safety, 7, pp. 159–162.

Davies, H. and Mannion, R. (1999) ‘Clinical governance: Striking a balance between checking and trusting’. Centre for Health Economics – discussion paper 165, online at: www.york.ac.uk/media/che/documents/papers/discussionpapers/CHE%20Discussion%20Paper%20165.pdf (last accessed 25 January 2016).

Dent, M. (2006) ‘Patient choice and medicine in health care: Responsibilisation, governance and proto-professionalisation’. Public Management Review, 8(3), pp. 449–462.

Dibben, M. and Lean, M. (2003) ‘Achieving compliance in chronic illness management: Illustrations of trust relationships between physicians and nutrition clinic patients’. Health, Risk and Society, 5(3), pp. 241–248.

Dixon-Woods, M., Yeung, K. and Bosk, C. (2011) ‘Why is UK medicine no longer a self-regulating profession? The role of scandals involving “bad apple” doctors’. Social Science & Medicine, 73(10), pp. 1452–1459.

Elston, M. A. (2009) ‘Remaking a trustworthy medical profession in twenty-first century Britain?’. In J. Gabe and M. Calnan (eds) The New Sociology of the Health Service, pp. 17–36. London: Routledge.

Flynn, R. (2002) ‘Clinical governance and governmentality’. Health, Risk and Society, 4(2), pp. 155–170.

Freidson, E. (1970) Profession of Medicine: A Study of the Sociology of Applied Knowledge. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

Fugelli, P. (2001) ‘Trust in General Practice’. British Journal of General Practice, 51, pp. 575–579.

Furedi, F. (1997) Culture of Fear: Risk Taking and the Morality of Low Expectation. London: Cassell.

Gabe, J. and Elston, M. A. (2008) ‘“We don’t have to take this”: Zero tolerance of violence against healthcare workers in a time of insecurity’. Social Policy & Administration, 42(6), pp. 691–709.

Gale, N. (2014) ‘The sociology of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine’. Sociology Compass, 8(6), pp. 805–822.

Giddens, A. (1990) The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Greener, I. (2003) ‘Patient choice in the NHS: the view from economic sociology’. Social Theory and Health, 1(1), pp. 72–89.

Hall, M., Dugan, M., Zheng, B. and Mishra, A. (2001) ‘Trust in physicians and medical institutions: What is it, can it be measured, and does it matter?’. Millbank Quarterly, 79(4), pp. 613–639.

Ham, C. and Alberti, K. (2002) ‘The medical profession, the public and the government’. British Medical Journal, 324, pp. 838–841.

Harrison, S. and Smith, C. (2003) ‘Neo-bureaucracy and public management: The case of medicine in the National Health Service’. Competition and Change, 7(4), pp. 243–254.

Hohl, K., Stanko, B. and Newburn, T. (2013) ‘The effect of the 2011 London disorder on public opinion of police and attitudes towards crime, disorder, and sentencing’. Policing, 7(1), pp. 12–20.

Jalava, J. (2006) Trust as a Decision: The Problems and Functions of Trust in Luhmannian Systems Theory. PhD thesis, University of Helsinki.

Kirsch, I., Deacon, B., Huedo-Medina, T., Scoboria, A., Moore, T. and Johnson, B. (2008) ‘Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: A meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration’. PLOS Medicine, 5(2), e45.

Kuhlmann, E. (2006) ‘Traces of doubt and sources of trust: Health professions in an uncertain society’. Current Sociology, 54(4), pp. 607–620.

Le Grand, J. (2010) ‘Knights and knaves return: Public service motivation and the delivery of public services’. International Public Management Journal, 13(1), pp. 56–71.

Luhmann, N. (1979) Trust and Power. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Luhmann, N. (1988) ‘Familiarity, confidence, trust: Problems and alternatives’. In D. Gambetta (ed.) Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations, pp. 94–108. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Mechanic, D. (2001) ‘How should hamsters run? Some observations about sufficient patient time in primary care’. British Medical Journal, 323, pp. 266–268.

Möllering, G. (2005) ‘The trust/control duality: An integrative perspective on positive expectations and others’. International Sociology, 20(3), pp. 283–305.

Moran, M. (2003) The British Regulatory State: High Modernism and Hyper-Innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MORI (2004) In Search of Lost Trust. London: MORI.

Newburn, T. (2014) ‘Civil unrest in Ferguson was fuelled by the Black community’s already poor relationship with a highly militarized police force’. LSE American Politics and Policy (29 Aug 2014) Blog Entry. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/59363/ (last accessed 25 January 2016).

Parsons, T. (1975) ‘The sick role and the role of the physician reconsidered’. Millbank Quarterly, 53(3), pp. 257–278.

Poortinga, W. and Pidgeon, N. (2003) ‘Exploring the dimensionality of trust in risk regulation’. Risk Analysis, 23(5), pp. 961–973.

Power, M. (2003) ‘Evaluating the audit explosion’. Law and Policy 25, pp. 185–202.

Power, M. (2004) The Risk Management of Everything: Rethinking the Politics of Uncertainty. London: DEMOS.

Rijksoverheid (2012) Geneesmiddelenwet. [Medicines Act]. The Hague: Dutch Government.

Rijksoverheid (2013) Wet op de Omzetbelasting [Sales Tax] 1968. The Hague: Dutch Government. Artikel 11, g, 1; Policy revision made on 14 May 2013.

Rothstein, H. (2006) ‘The institutional origins of risk: A new agenda for risk research’. Health, Risk and Society, 8(3), pp. 215–221.

Rowe, R. and Calnan, M. (2006) ‘Trust relations in health care: Developing a theoretical framework for the “new” NHS’. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 20(5), pp. 376–396.

Sheaff, R. and Pilgrim, D. (2006) ‘Can learning organisations survive in the new NHS?’. Organisational Science, 1, p. 27.

Siahpush, M. (2000) ‘A critical review of the sociology of alternative medicine: Research on users, practitioners and the orthodoxy’. Health, 4(2), pp. 159–178.

Solbjør, M., Skolbekken, J. A., Saetnan, A., Hagen, A. and Forsmo, S. (2012) ‘Mammography screening and trust: The case of interval breast cancer’. Social Science & Medicine, 75(10), pp. 1746–1752.

Spyridonidis, D. and Calnan, M. (2011) ‘Are new forms of professionalism emerging in medicine? The case of the implementation of NICE guidelines’. Health Sociology Review, 20, pp. 394–409.

Strathern, M. (2000) ‘The tyranny of transparency’. British Educational Research Journal, 26(3), pp. 309–321.

Taylor-Gooby, P. (2006) ‘The rational actor reform paradigm: Delivering the goods but destroying public trust?’. International Journal of Social Quality, 6(2), pp. 121–141.

Thomas-Symonds, N. (2010) Attlee: A Life in Politics. London: I.B. Tauris.

VtdK – Vereniging Tegen de Kwakzalverij (2010) ‘Handelaren in valse hoop’. www.kwakzalverij.nl/756/Handelaren_in_valse_hoop (last accessed 25 January 2016).

Waring, J., Dixon-Woods, M. and Yeung, K. (2010) ‘Modernising medical regulation: Where are we now?’. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 24(6), pp. 540–555.

Warner, J. (2015) The Emotional Politics of Social Work and Child Protection. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.