Professions and the migration of expert labour

Towards an intersectional analysis of transnational mobility patterns and integration pathways of health professionals

Whereas internationally mobile professionals find many more opportunities than in the past, the migration of professionals across countries is not in itself a new phenomenon. Indeed, the esoteric nature of professional knowledge is such that it can transcend national boundaries, at least theoretically. What is new is the number of countries participating in the transnational migratory movements of professionals, the rapid increase in the pace of the movement of professionals internationally, the impermanency of their migration decisions, and the growing politicization of migration (Castles and Miller, 2003). These new dynamics are transforming not only the lives of the internationally mobile professionals but the overall composition of the professional workforce and its social organization. In this chapter we use the concept ‘mobilities’ in parallel to migration to denote how the numerous new patterns of spatial mobility of professionals are transforming the social organization of professions, in ways that disrupt the very idea of professions as nationally bounded social phenomena. Indeed, we argue that a better understanding of professional mobilities has implications for all future theorizing about professions in the era of transnational globalization.

Transnational mobilities of professionals occur in new types of social networks and economic contexts that shape the mobility patterns and integration pathways of professionals. These complex mobilities can be seen as a reflection of economic globalization and the related increasing competition for international talent that has brought about new transnational flows and mechanisms (Yeates, 2009). This increased pace of professional migration raises important equity concerns, including the emigration of highly trained professionals (‘brain drain’) from so-called ‘source’ countries of the less-resourced south to destination countries in the more-resourced global north (cf. Kapur and McHale, 2005).

Internationally mobile professionals, whose strategic actions can maximize their economic circumstances and earning potential within a globalizing market, may possess significant mobility capital, defined as capacities and competencies, in relation to the surrounding physical, social and political affordances for movement (Kaufmann et al., 2004). Differential capacities and potentials for mobility are identified in the literature with the concept of ‘motility’, referring to ‘the manner in which an individual or group appropriates the field of possibilities relative to movement and uses them’ (Kaufmann and Montulet, 2008, p. 45). While professional expertise per se constitutes an attractive resource in the context of global competition for expert labour, professions differ when it comes to motility (i.e. the ease with which their expertise travels). For example, many areas of engineering, commercial and corporate law, economics, consulting and accounting have been directly influenced by the rise of an international arena of professional business, giving rise to a transnational labour market linked to such new types of service work; these are the types of transnational professionals to which Sassen (1988, 1998, 2007) refers in her analyses. By way of contrast, many human service professions, such as health care, teaching or social work, continue to be shaped by a low degree of mobility due to the ties that bind them to specific national settings and to the strict rules regarding skills assessment requirements (cf. Bourgeault et al., 2010; Wrede, 2010).

Professional mobilities are also highly gendered, classed and ‘racialized’ in ways that condition both who can be mobile and how and what kind of consequences particular mobility patterns have in origin and destination countries. While traditionally migration was analysed as ‘male’ movement, today women often outnumber men in transglobal movement (Camilin et al., 2014; Ryan, 2002), although some countries continue to restrict women’s migration due to patriarchal ideologies (Kingma, 2006). The literature now speaks of a feminization of migration, referring to how more women are migrating, not only in the professions, though the caring professions are most notable. Women’s migration has given rise to global care chains, a term first coined by Hochschild (2000) to denote how migrant care workers fill the care deficits left by women’s increased labour force participation in destination countries but at the same time women’s emigration creates care deficits in their countries of origin.

This chapter considers transnational professional migration and integration from an intersectional perspective recognizing the interconnectedness of professional identities and associated hierarchical structures relating to, for example, gender, ethnicity, race and class at different levels of society (cf. Anthias, 2012). We undertake this examination through the case of the health-care professions, with a specific focus on medicine and nursing. The health-care professions constitute a particularly interesting case that transcends the continuum between purely transnational labour markets and persistently nationally rooted professional occupations.

Health-care delivery in the global north represents a labour-intensive growth industry. Despite welfare state austerity, the demand for more health-care workers is constantly growing due to demographic and epidemiological trends of population ageing and the rising prevalence of multiple chronic conditions. The demand for health labour is compounded by the ageing of the local health workforces. Not surprisingly, recruiters of health professionals from high-income countries scout for new labour pools globally; in the OECD 11 per cent of employed nurses and 18 per cent of employed doctors were foreign-born (OECD, 2007, p. 162). The sheer magnitude of the flows of internationally mobile health professionals has sparked significant policies to address the ethics of international recruitment practices globally (e.g. World Health Report, 2006, 2010).

To capture the situatedness of professional mobilities, we need also to distinguish mobility/migration – the decision to leave a country for another – and the settlement/integration of the mobile professionals into a particular local professional labour market. Moreover, integration is more complex than the attainment of licensure to practice; it also concerns broader social and cultural integration. The drivers of professional migration briefly noted above may be similar across types of professions – but the integration processes and possibilities for internationally mobile professionals are very much tied to the integration pathways that are available in local contexts, particularly for the highly regulated health professions. Such complexity calls for analytical approaches that not only are sensitive to context but serve to tease apart the complex drivers of migration from the forces influencing the integration of migrating health professionals.

In this chapter, we review the literature examining the migration and integration of health professionals to help elucidate the distinction between globalized migration and localized integration. We then draw upon theoretical inspirations from the overlapping sociology literatures on migration, the professions and globalization, with an aim of outlining a pluralistic conceptual framework for the intersectional analysis of professional mobilities that recognizes that migration and integration have their interlinked but separate, complex dynamics. This analytic framework separates micro, meso and macro influences. The meso level, we argue, is particularly important to more fully understand local professional integration processes whereby transnationally mobile professionals are integrated into a local labour market that is controlled nationally or subnationally. An emphasis on the integration pathways that are constituted through interactions and mechanisms that operate at meso level also highlights the important contributions to these trends that literature on the professions can play and that has heretofore been neglected.

Health professional migration: an overview of micro, meso and macro influences

Health professional migration is a multi-layered phenomenon with a complex history. Historically, an internationally mobile workforce generally moved along established pathways between countries that often had their roots in colonial ties (see e.g. Choy, 2003). This was particularly notable of the Commonwealth countries and exemplified through the historically relatively straightforward migration of doctors and nurses among the UK, Australia, Canada and South Africa. From a colonial perspective, the Filipino government was the first to tap into the expanding health labour demand brought about by neoliberal globalization in the 1980s (Choy, 2003). The dynamics of health professional migration thus reflect the deep social-economic and political divisions that have come to be identified as the North–South divide that underpins the global inequalities between affluent countries and countries that lack resources. In the 1990s and 2000s, governments in the global south as well as private firms, often located in the global north, followed suit. In the present context, numerous source countries already cater for nearly all countries of the global north. While the numbers of mobile health professionals recruited to different countries varies, it is obvious that workforce planning in the global north has become a transnational practice that is structured by the uneven social development in different parts of the world.

In order to analyse the multi-layered nature of health professional migration, it is helpful to tease apart the various levels of analysis prevalent in its literature. We begin with the more micro or individually focused level of analysis which emphasizes the motivational factors affecting individual migration decisions, including how the migration and integration processes are experienced personally. The next most frequent focus in the literature is at the macro or political economic level which addresses, among other issues, the impact of globalization on labour markets for professional services, the impact of health professional migration on source and destination countries, and how these processes are shaped by intersecting inequalities. In general, there has been a neglect of the meso or institutional factors, including the roles played by intermediaries such as employers, professional certifying and regulatory bodies, professional associations and trade unions in destination countries (Bach, 2003). It is important to note that the teasing apart of these factors is for heuristic purposes only, because there is, as we will argue further below, significant interaction of the different levels.

Micro/individual level of analysis

The mainstream literature on health professional migration is dominated by a more or less implicit rational-choice perspective that focuses on the health professionals who migrate, analysing the social, political but largely economic reasoning underpinning their decisions to migrate. This labour-market-oriented research often emphasizes how certain ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors operate at a micro or individual level, although some of the push and pull factors are often a direct result of macro, structural forces. Pull factors include the individual perceptions or experiences of better and more comfortable living and working conditions, and higher wages and opportunities for advancement (Aiken et al., 2004). Overall, the literature identifies poor wages, economic instability, poorly funded health-care systems, the burdens and risks of AIDS and safety concerns as factors that push health professionals to leave less-resourced countries (Aiken et al., 2004; Robinson and Carey, 2000).

Although this model is often cited in the migration literature, it tends towards a taxonomy, listing and describing factors, with little attention to the dominance of some factors over others, the root causes of some of these individual factors at a broader level and the interrelationship between push and pull factors. Kingma (2006) notes, for instance, that ‘pull factors’ do not solely account for mass exodus of health-care professionals from less-resourced areas of the world. Walton-Roberts (2015) similarly critiques this approach for focusing almost exclusively on labour-market conditions and failing to appreciate the role played by the broader political economy and local health professional educational systems, which we discuss more fully below. This perspective can also be critiqued for neglecting colonial relations, gender and other social divisions in its analysis of the migration dynamic (Hagopian et al., 2005). We add to these critiques that analyses focusing on push and pull factors may result in a narrow understanding of the reasoning that goes into decisions to migrate. If people are primarily approached as labour-market agents, ignoring both their private concerns and other than economic work-related aspirations, including those of professional character.

Researchers have also been interested in the integration experiences of health-care workers in their countries of destination. Despite significant differences in the countries of origins of migrating professionals, they experience remarkably similar processes of struggling to become integrated. Research shows that newly immigrated professionals often feel alienated from other members of their profession when integrated (Neiterman et al., 2015) and report discrimination in their new workplaces. Indeed, the majority of these studies deal with the racism and discrimination that health-care workers face in the country of destination (Alexis and Vydelingum, 2004; Collinds, 2004; Hagey et al., 2001; Larsen, 2007). Qualitative studies often explore how immigrant health workers are discriminated against according to race and denied career opportunities (Allan et al., 2004; Dicicco-Bloom, 2004; Turrittin et al., 2002). The instances of discrimination and racism at the workplace are especially prevalent in the nursing literature (Allan et al., 2004; Dicicco-Bloom, 2004; Hagey et al., 2001; Kingma, 2006), but it is also evident of women physicians (Giri, 1998), suggesting the importance of accounting for gender as an important dynamic in racism and discrimination.

While experiences of racism and discrimination of health workers have been documented by researchers, less is known about the process of integrating into a new country’s local labour and culture of practice. Indeed, much of the literature on health labour migration at the micro level lacks knowledge of the psychosocial experiences of health-care immigrants and how they negotiate the labyrinth of policies and procedures to practise their profession. A great deal of what we know comes from the studies undertaken by Shuval and her colleagues (Bernstein and Shuval, 1998; Shuval, 1995, 1998, 2000) of the massive emigration of physicians from the Soviet Union to Israel when it had an open, non-selective migration policy. Not surprisingly, these studies found that Soviet physicians who migrated to Israel and who were working in their profession had significantly higher well-being scores than those not working as physicians. Yet many of those physicians who were working in their chosen profession were dissatisfied with their allocation to less prestigious practice settings, with the lack of recognition of their professional backgrounds, and with the questioning of their authority by patients. The salience of professional identity is critical among immigrants who see their occupational status as core to their self-identity (Bernstein and Shuval, 1998). How this was experienced differentially by male and female physicians and those of different minority backgrounds was noted.

Building on this analysis, Neiterman et al. (2015) compared the situation of physicians migrating and integrating in Canada and Sweden utilizing the theoretical literature on othering and belonging. They argued that the construction of professional identity among migrating physicians necessitates constant comparison between ‘us’ – immigrant physicians, and ‘them’ – local doctors. In this process, one’s ethnicity and professional status are intertwined with the experience of being seen as ‘other’. Adjusting to the local culture of practice, migrating health professionals undergo a process of professional resocialization, learning the new professional landscape simultaneously with learning the cultural norms of the host country (see also Neiterman and Bourgeault, 2015a).

In brief, the micro literature focuses on both the migration and integration processes, and in recent years the traditional focus on push-pull factors has expanded to include, alongside political and economic reasons, also personal motives for migration. Increasingly, intersectional approaches that account for social divisions and cultural processes have started to appear.

Macro/political-economic level of analysis

While micro-level studies have expanded in scope, they still often remain under-contextualized. Macro-level analyses augment the micro dimension in a way that links the migration of health-care workers to broader economic forces. These analyses often take an ethical standpoint; authors opposing the migration of health professionals highlight the losses to the less-resourced countries of their highly qualified health-care personnel (Ahmad et al., 2003; Buchan, 2004; Jeans, 2006; Labonté et al., 2006), while the proponents of such movement highlight the economic benefits that remittances of migrant health-care workers return to their countries of origin (cf. Guarnizo, 2003). Similarly, the cost–benefit analysis of the use of the imported health-care workforce in the countries of destination has demonstrated how the recruitment of health-care workers from abroad helps more resourced countries to save millions on the training of health-care personnel (Labonté et al., 2006). These and other ethical concerns are raised in a context where recruitment is emerging as a growing, increasingly transnational industry (e.g. Pittman et al., 2010), and where there is a huge discrepancy between countries with high burdens of disease and disability and wealthier and comparatively well-resourced countries (Eckenwiler, 2014).

Because of the ethical dilemmas of recruiting health personnel from less-resourced nations, the British National Health Service (NHS) produced a Code of Practice for NHS employers involved in the international recruitment of health-care professionals (NHS, 2001) prohibited direct recruitment of nurses from Africa. It did not, however, initially cover private sector employers, but because the NHS recruits from private employers, its own Code was circumvented. African nurses continued to emigrate to the UK (Aiken et al., 2004). Later Commonwealth countries in 2004 developed a similar Code of Practice, but it too was limited by coverage and lacked an enforcement mechanism. These limitations hold true to a certain extent for the WHO Code recently signed by all countries in 2010, even though it covers the widest possible range of employers in both the public and private sectors, and includes NGOs, professional associations and regional health authorities (Bourgeault et al., forthcoming). Notwithstanding the ethical issues arising from active recruitment, another ethical dilemma associated with the international migration of health professionals is in their effective integration when they choose to migrate so as not to let their skills go to waste (Bourgeault, 2007). This issue has only been addressed in the most recent WHO Code. These codes have, however, failed to stem the tide of migrating health workers largely because they are voluntary, have no financial implications, and because they are difficult to apply to the rapidly growing involvement of private-sector recruitment agencies (Labonté et al., 2006; Tankwanchi et al., 2014).

The resulting flows of human and economic capital from lower- to higher-resourced countries can be linked to the historically colonial nature of the relationship between nations. In the past, old colonial ties gave rise to migration pathways between Australia, Canada and the UK, similarly to the migration in the Nordic region, where low cultural distance facilitated health professional mobility (Bourgeault and Wrede, 2011). Drawing on post-colonial theory, McNeil-Walsh (2004) seeks to explain the migration and easy integration of South African nurses to the UK. She describes how Britain, as a colonial power, shaped the structure of South African society, including its health-care delivery and education system. South Africans therefore had an immigration advantage with policies that recognized their British-like credentials and immigration policies which favoured those who hailed from the former colonies to move to Britain without restriction. Any thorough analysis of current migration trends cannot, according to McNeil-Walsh (2004), ignore this historical context. The historical context in which migration of health-care workers was established from the colonies also cannot be reduced to simple economic explanations. For instance, scholars have found the culture of migration to be firmly rooted in Nigerian and Ghanaian physicians’ visions of their medical future – to move to the West upon completion of their education (Hagopian et al., 2005).

Other literature stresses the importance of looking beyond the particular policy contexts of the nation state, or its pre-existing colonial ties, to understand the broader impact of trade agreements, such as the European Union (EU), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) on the flow of health labour (Bach, 2003; Orzak, 1998). These trade agreements urge national governments to reduce or eliminate requirements and regulatory devices that impede or block the movement of goods and services. So where national boundaries historically separated licensing, regulatory and credentialing systems, the facilitation of enhanced international trade in services may weaken the autonomy and authority of nationally based professional regulatory systems (Orzack, 1998).

The EU, for example, has been keen to promote the free movement of labour as well as encourage migration into certain regions and sectors. The EU has established an inclusive model of mutual recognition of qualifications in which a number of regulated health professionals, including physicians and nurses, are free to work in any other member states. Similarly, NAFTA has made it easier for some Canadian nurses to find work in the USA (Aiken et al., 2004), but there has not been a similar migration of nurses from Mexico to the United States, due largely to issues of educational equivalence (Squires, 2011). This speaks to the importance of the meso regulatory level, discussed more fully below.

The overarching GATT also facilitates increased labour migration because of its efforts towards aligning the competency and recognition requirements for health professionals between countries. This has had important impacts on the education systems in source countries, shifting their orientation from local health-care needs to global health workforce markets. Indeed, there are overarching trends towards the internationalization of health professional education which is typically focused on standards in well-resourced countries of the north. Choy’s (2003) analysis of the nursing export labour policy of the Philippines reveals how its educational system under US neo-colonialism became structured toward US health-care market demands, with most nursing schools following US-based curricula and utilizing US-based textbooks. Walton-Roberts (2015) describes this in the case of nursing training in India, and specifically on how the increasingly private and indeed corporate health-care training systems evolving in India are more and more aligned with the production of professionals dominated by US-based curricula and orientated to globally integrated health labour markets. She argues for a global political economy approach in order to better understand the impact of the rise of international health human resource systems and circuits and how practices originating outside of the state, involving interaction and integration across and between places and scales, are comprising, altering and constraining ‘national’ processes (p. 375).

In sum, macro-level analyses help to elucidate the broader contextual factors influencing migration, why health professionals move from where and to where, and also in terms of highlighting dynamics related to gender, ‘race’ and ethnicity. Attention to the meso level of analysis would, however, help to contextualize the agency of migrating health professionals by elucidating some of the structural constraints on their actions when they attempt to and become integrated into local labour markets.

Meso/institutional level of analysis

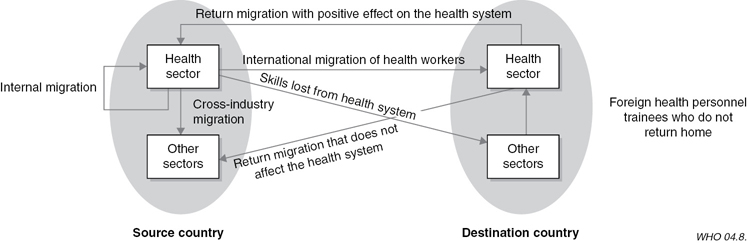

As noted above, meso-level analyses are less frequent in the health professional migration literature. It is not accidental that the notable exceptions focus more on professional integration processes than the migration decision. Diallo (2004) elucidates the distinction between the migration decisions and actions of health professionals and the contextual factors and forces influencing their integration into the local professional market. In Figure 20.1, Diallo (2004) teases apart the process and outcomes of migration from integration and also captures both the primary and return migration trajectory that may be evidenced for some migrating health professionals. In addition, the figure helps us to visualize how skills can be lost to source countries (i.e. ‘brain drain’) but also to destination countries (i.e. the ‘brain waste’ issue noted above) when migrating health professionals work in sectors other than health.

One of the earliest scholars to undertake a more meso-level analysis of the integration of health professionals is Shuval and colleagues (1995; Bernstein and Shuval, 1998) in the examination of the experiences of Russian émigré physicians in Israel discussed above. The context in Israel for these integration efforts was marked by an already oversaturated medical market exemplified by under- and unemployment. The migration of over 12,000 Jewish physicians from the Soviet Union between 1989 and 1994 essentially doubled the supply of physicians in Israel. Although there has never been overt opposition to the entry of immigrants by the established medical profession in Israel, Shuval (1995) describes three key strategies undertaken in response to this flooding of the medical labour market: (1) the Israeli medical profession applied stringent quality control with regard to the licensure of migrating physicians, including the same qualifying examinations as those administered to Israeli medical graduates, but strictly limited to general practice in the primary care system; (2) senior Israeli physicians exerted full control of the employment options for Russian émigrés in the local health-care system; and (3) Israeli physicians promulgated widespread negative stereotypes regarding the professional skills of immigrant physicians. These three strategies together served to exclude a sizeable proportion of the émigré physicians from practising as physicians in Israel.

Groutsis’ (2003) examination of the integration paths of overseas doctors in Australia focuses similarly on the meso level. She juxtaposes the role of the state, as the major driver of policy shifts enabling the migration of overseas-qualified health-care professionals, with the role of the local medical profession, a group that has exercised its professional power to operate above and beyond the state’s interest in controlling health professional supply conditions. Groutsis’ (2003) analysis reveals how the medical profession’s strict control of the registration of migrating physicians, and therefore their labour market access, through its licensure examination was met with a more activist approach by the state. This was afforded through policy ‘work arounds’, such as the Areas of Need programme, which enabled the direct recruitment of overseas-trained doctors with a restricted licence to work in remote locales for a period of up to ten years.

Similarly, studies of professional integration in Nordic countries have problematized other features of professional integration. As noted above, the member countries of the EU are obligated to mutually recognize the professional qualifications of professionals from other member countries. EU rulings do, however, recognize the need for language controls which thus become the key focus for defining the conditions of entry for mobile EU nationals (see European Commission, 2013). A Norwegian study focusing on the experiences of health professionals found that even when they were working in their profession, they often encountered exclusion related to a dynamic in which ‘Norwegianness’, defined as locale-specific cultural knowledge, has emerged as an important informal criterion of competence (Dahle and Seeberg, 2013). Other Nordic research has uncovered similar ethnic hierarchies in organizations that do not recognize the institutional racism involved in work organization that privileges locale-specific cultural knowledge (Laurén and Wrede, 2008); deteriorated terms of employment within welfare services, as well as institutional racism negatively impacting the families of the mobile professionals (Isaksen, 2010); and the rise of ‘migrancy’ as an exclusionary boundary within the medical profession that assigns immigrant doctors to low-prestige positions within the profession (Salmonsson, 2014).

Thus, one of the key problematics at the meso level is how migrating health professionals integrate and the multiple meanings this has both for their integration context and for their social position in the destination country. Integration involves admittance into often highly regulated fields of practice controlled by local professional organizations, as well as assimilation into the culture of the health-care system and local health professional practice. For example, in the case of the Russian émigré physicians in Israel who were able to secure a licence, they expressed dissatisfaction with the questioning of their authority by Israeli patients (Bernstein and Shuval, 1998), showing that complex ethnic boundaries may result from the integration of foreign personnel, requiring attention from the perspective of discrimination.

The gendered dynamics of health professional migration in the era of transnational mobilities

More recent analyses of health professional migration depict an even more complex picture than the terms ‘source’ and ‘destination’ country entail, emerging in the current era of transnational health professional mobilities. Some countries can be both source and destination, to varying degrees. For example, while Canada has both historically and more recently relied on migrating health professionals to help solve shortages in particular areas and sectors, there have been, from time to time, laments about its own health-care ‘brain drain’ to the United States. Similarly, while Ireland still provides a great deal of nursing labour to neighbouring countries, especially, it has recruits from other labour markets, most notably the Philippines (Yeates, 2004). Beyond this dynamic, there is an increasing trend of ‘chain’ migration and ‘transition’ countries, particularly through the Middle East (of which we know very little), which reflects a decreasing permanence of professional migration. Figure 20.2 represents this type of chain migration using the OECD countries as an example.

Some of the reasons behind particular chains of migration may reflect post-colonial ties between specific localities, as noted above. Other drivers result from the global political economy of the increasingly prevalent bilateral and multilateral agreements, both those that explicitly address health professional migration as well as those agreements for which health professional migration is incidental (e.g. trade agreements).

Scholarly research framed by approaches rooted in globalization and feminist political economy have increasingly studied such mobilities as gendered (Walton-Roberts, 2015). The literature on the migration of nurses has particularly considered how gender is implicated in the migration decisions of health-care workers through gender discrimination, inequality, traditional societal attitudes towards female migration and gender-based networks (e.g. Adhikari, 2013; Byron, 1998; Ryan, 2008). Ryan’s (2008) work on Irish nurses who migrated to Britain in the post-war period reveals, for instance, that most of them were encouraged to migrate by female relatives, especially sisters, aunts and cousins. Adhikari (2013) illustrates how female nurses in Nepal are encouraged to migrate by their families as their migration is seen as collective family investment. Although the same could be said about male migration, female migration is a relatively new phenomenon because it overcomes previous (and in some places continued) restrictions on women’s mobility which are rooted in patriarchal relations. Moreover, being a son who migrates versus being a daughter has very different social implications, not the least of which are social issues of purity and economic issues of family remittances. It is also important to note that the gendered meanings of family ties change over time. Transnational mobilities may serve to disrupt traditional gender roles and relations within the family at a relatively rapid pace, as shown by George’s (2005) examination of the migration of nurses from Kerala, India, to the United States.

As noted above, the concept of ‘global care chains’ has also been applied in the case of more highly skilled health professional work. Yeates (2004), for example, argues that the concept enriches our understanding of the complex relationship between international migration and care-giving, which helps to contextualize the migration of nurses. The burden of the global care chain can have multiplicative negative effects on the lives of these women in terms of increased workload and social isolation (Bourgeault, 2015; Eckenwiler, 2014).

When examining the process of professional integration, gender is similarly important to consider. Some researchers have found, for example, that women physicians seem to adjust to a new system better than men (Remennick and Ottenstein-Eisen, 1998), but others have noted greater psychological distress among female health professionals who migrate (Factourovich et al. 1996). Given that they tend to shoulder greater family responsibilities, many female migrating health professionals have been found to delay the process of accreditation, retraining and occupational integration in favour of supporting their male spouse (Bernstein and Shuval, 1998; Neiterman and Bourgeault, 2015b).

In a comparison of the experiences of discrimination among nurses and doctors coming to Canada from abroad, Neiterman and Bourgeault (2015b) found that there is an interplay of ethnic, gender and professional inequalities in the instances of discrimination and racism to which these migrating health professionals are exposed in their workplace (cf. Hankivsky et al., 2010). Migrating nurses tend to be exposed to more instances of discrimination and racism than physicians. The status of the medical profession can serve as a shield of protection from the experiences of racism and discrimination. That is, the relatively high status of the profession of medicine and the lower status of nursing, a profession considered inherently ‘feminine’, suggests that the role of gender and professional status intersect in the experiences of discrimination.

In sum, the emergence of globalized health labour markets entails that mobility pathways become more diverse, but these mobilities continue to be structured by gender that intersects with other local and global forms of inequality, such as ethnicity, ‘race’ and class. These sociocultural hierarchies further intersect with conceptions of professionalism and skill that are always situated and socially constructed along gender lines (Wrede, 2010).

Building a pluralistic framework for the intersectional analysis of mobility patterns and integration pathways of health professionals

We have made the case for the importance of a multi-layered analysis that includes micro, meso and macro levels, with attention to the intersections of gender, ethnicity, class, etc. as cross-cutting features. In this section we will use this structure to develop a conceptual framework that marries theoretical approaches to migration and professions with theoretical insights from studies of globalization and transnationalism. Instead of lamenting ‘the absence of a single, coherent, interdisciplinary theory that is able to explain the full complexity of the migration processes’ (de Haas, 2010), we argue for the need to be more pluralist in seeking different and ideally complementary theories to explain the different layers of the factors and forces influencing professional migration in a way that links these analyses.

We propose a pluralistic conceptual framework of theories, not an overarching theory in and of itself. Figure 20.3 begins to tease apart the various layers of analysis and their impact on migration and integration separately (though there are some for which there is overlapping influence) and maps some of the different theories next to the factors and forces they emphasize; we highlight in the text below a few of these theoretical perspectives, particularly those which draw upon professions theory. An intersectionality lens, described above as including critical social divisions such as gender, ethnicity, class, etc., cuts across all levels of analysis as well as the migration and integration processes. This is important because the, identification of interlinkages is necessary in order to grasp the complexities of mobility patterns and integration pathways.

Micro-level theoretical inputs

We acknowledged above that health professionals from different countries and in different professions have access to differential capacities and potentials for mobility. It is important to note how more conventional understandings of migration tend to ignore such differences and instead assign ample room for individual migrants as strategic actors. This kind of research on expert labour tends to draw from classical migration theory that builds on neoclassical economic theory and economic spatial analyses. For example, such approaches assume that migration decisions are powerfully influenced by how individuals assess supply and income differentials (without acknowledging how these differentials arise). Early migration studies sought to demonstrate how such assessments lead to an equilibrium of workers moving to a context of low supply and higher incomes (e.g. Harris and Todaro, 1970). Other early theories of migration developed spatial approaches, focusing, for example, on an interplay between distance and opportunities for migrants (Stouffer, 1940) or on ways that migrants move within established ‘streams’ where there is a pre-existing flow of workers and information (Lee, 1966).

Analyses that assume the autonomy of professional migrants as strategic actors shaping their transnational careers have an intuitive appeal and may indeed be undertaken, but in and of itself this is an insufficient and inadequate framework for analysing mobility patterns and integration pathways. There is agency involved, but there are also structural determinants which ultimately affect the weight of push and pull factors. This perspective does not, as Hazarika (2015) describes, ‘take into consideration factors such as human capital characteristics, segmentation of destination country labour markets as well as immigration policies that are important determinants in the migration process’ (p. 22).

Social and cultural dimensions are also explored in migrant network theories (Massey et al., 1993), which are described as ‘sets of interpersonal ties that connect migrants, former migrants, and non-migrants in origin and destination areas through bonds of kinship, friendship, and shared community origin’ (p. 448). Massey et al. (1993) further argue that migrating can become self-perpetuating once a critical mass of migrants establishes a de facto social structure enabling migration. Connell (2008) writes about how such a culture of migration is endemic to the Pacific Islands such that the retention of health workers seems impossible.

With respect to the integration side of the framework, we could draw more fully on professional socialization theory to examine how the integration experiences of mobile health professionals involve a process of professional resocialization (Neiterman and Bourgeault, 2015a). These reworked concepts are helpful in denoting how migrating health professionals must learn a new local professional culture in their new country, layering over their original professional socialization in their home country.

Meso-level theoretical inputs are at the local labour market level reflecting both economic supply and demand factors that affect social-closure activities of professional groups. Here we can build upon Shuval (1995) and colleagues’ (Bernstein and Shuval, 1998) application of a professional closure model by broadening this to include a more dual or parallel systems focus from the work of Abbott (1988). Shuval explored the intra-professional tensions in the Israeli medical profession when confronted with the massive emigration of physicians from the Soviet Union by drawing upon a professional closure model (Parkin, 1979). Briefly, this approach delineates how exclusion based on credentials serves to limit and control the supply of entrants to professional practice, depending on the key market factors of need, supply and distribution. Using this approach, Shuval describes how Israeli physicians maintained control over international medical graduates in a highly saturated medical market.

To expand, social-closure theorists within the sociology of professions describe the relations between professions when boundaries of professional jurisdiction are negotiated within a single-system perspective (Abbott, 1988); they also analyse the dynamics within professions, such as the inclusion or exclusion of particular subgroups. Indeed, Witz (1992) utilized the concepts of inclusion and exclusion to describe the historical treatment of women in medicine in Britain. Analyses of the dynamics of inclusionary and exclusionary social closure strategies have tended to focus more narrowly on the dynamics within a nationally bound profession. Indeed, these internal dynamics within nationally bound health systems (and their consequences) are increasingly under scrutiny/surveillance and/or problematized by a range of stakeholders external to national systems.

What might be useful would be an expansion of Abbott’s (implicitly nationally focused) system to include dual or parallel systems of professions in ‘source’, ‘destination’ and transit countries influencing the migration pathways of health professionals. Visually, these could be represented by the two circles in Figure 20.1 as the ‘source system’ and the ‘destination system’, acknowledging the important distinctions made in that figure. Inclusion and exclusion could still be utilized as the main tools of social closure. Migration (in, out and return) of the parallel systems could be considered as external system disturbances (drawing upon Abbott’s terminology) influencing jurisdiction within nationally bound professions. But there are also a number of other external system disturbances reflecting more macro-level inputs (codes of practice, trade agreements, etc.), which would enable a natural tie from meso- to macro-level analyses. This conceptualization would also enable the recognition of highly segregated/regulated internal systems – which could help to address what is sometimes a ‘brain waste’ phenomenon in destination countries. It would also help to recognize the inequalities between ‘source’ and ‘destination’ countries – which addresses the more typically discussed ‘brain drain’ issues.

While a professional closure model may be useful in helping to explain the dynamics within a profession, it sometimes does not fully attend to the broader political and economic factors, including relations between various professional organizations and government agencies, which are critical to examine in the case of the integration of health professionals trained abroad. It can, however, incorporate a gender and intersectionality lens, as discussed above. Witz’s (1992) discernment of different types of gendered social closure strategies, for example, represents an as yet untapped resource in gendered analyses of health professional migration. That is, just as Witz (1992) encouraged us to gender the actors of professional projects, we argue here that we need to gender migrating health professionals. Gender matters in decisions to migrate and in the opportunities that male and female migrating health professionals have in integrating into local labour markets.

Macro-level theoretical inputs

Attention to the global political economy in research on the migration of health professionals draws from the rise of critical theorizing about globalization with roots in, among others, Wallerstein’s (1974) World System’s Theory. Wallerstein’s perspective is an important example of the historical-structural theoretical approach that describes how goods and capital flow from the powerful ‘core’ to the ‘periphery’ in search of raw materials, labour and new consumer markets. In the current context, critical approaches within a post-colonial global sociology seek to develop a sociology of connections that takes seriously the histories of interconnection that have shaped the current global inequalities (Bhambra, 2014). As implemented in the study of professional mobilities, Wallerstein’s theory of a world organized as centres and peripheries and Bhambra’s sociology of connections would allow us to understand professional mobility from peripheral locales in less-resourced countries to central locales in more-resourced countries and through them to marginal positions in their professional order as constitutive of the histories of the professions (see Bhambra, 2014, p. 155). This means recognizing that modern professions emerged in a colonial world, and that contemporary patterns of mobility make use of such historical connections as well as global ideas (Wrede, 2010).

Currently, the debates are formed around the practices of transnational communication and the impact of migration on the home and hosting countries’ economies and cultures (Levitt, 2001; Orum, 2005). While transnational studies incorporate many aspects of inquiry to better capture the dynamic of the relationship between migrants, host countries, and the countries of origin, scholars continue to engage in methodological and theoretical debates about what constitutes ‘transnationalism’, as well as how it should be studied and measured (Levitt and Jaworsky, 2007). Although definitions rendered by researchers of the transcultural movement vary, the vast majority of scholars appear to agree that research on migrants should contextualize the agency of migrants in the structural and institutional dynamics of both countries. This new approach is reflected in many works looking into the experiences of immigrants in their countries of destination. Scholars often link migrants’ personal experiences to the structural forces in their home countries and the modes of communication that shape their experiences as newcomers in their countries of destination (Behnke et al., 2008; Calavita, 2006; Waldinger et al., 2007)

The sociology literature has addressed the issue of professional migration as one of the key features in economic globalization. Sassen (1988, 1998, 2007), for example, describes the tensions between transnational economies and national migration policies. The author notes that ‘There is a causal relationship between immigrant receiving countries, foreign investment, and political-military and cultural involvement, on the one hand, and immigrant flows, on the other’(Sassen, 2007). Transnational economic policies, such as the World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Policies, have been critical in encouraging the large-scale out-migration of workers she terms an offshore proletariat. On the opposite end of the spectrum of the division of labour, she also describes the portable rights of a new transnational professional class, acquired through free-trade agreements, the International Monetary Fund and other such supranational institutions which can supersede national migration policies. These are indeed important insights but they may be less relevant to highly regulated local markets of certain professional domains, such as in health care. That is, national or subnational regulatory policies may still limit the integration of migrating professionals despite the system of health professions. Such regulations may serve as a mechanism for gatekeeping that may result in the emergence of a migrant division of labour within health professions where the transnationally mobile health professionals only have access to specific positions, not to equal inclusion (see Yeates, 2009; Wrede, 2010). This not only speaks to the continued importance of meso-level analysis, it also highlights how it is important to tease apart factors and forces influencing migration and those influencing integration. These are two overlapping yet distinct processes with different inputs and outputs.

In terms of the gender dimensions of translocal economic connections, Sassen’s (2002) analysis of the current transnational migration of women for largely female-typed activities identifies centres and peripheries as dynamic configurations, that is, as global cities and as sets of survival circuits emerging as a response to growing impoverishment of governments and whole economies in the global south. Even though Sassen’s ideas have often been applied to lower-skill workers, analyses that recognize the intersected inequalities ordering professional mobilities benefit from recognizing these connections as survival circuits that are often complex, involving multiple locations and sets of actors constituting increasingly global chains of traders and ‘workers’. Indeed, it is evident that health-care systems in the global north can build new economies of health care on the availability of supposedly rather valueless economic actors – low-wage and poor health professionals, the majority of whom are women.

In this chapter, we have categorized the literature on health professional migration according to different levels of analysis to inform the creation of a pluralistic theoretical framework that draws upon migration, globalization and professions theory. Our aim has been to build a basis for capturing the complexity of contemporary mobility patterns and integration pathways that are structured by intersecting global and local inequalities. A framework enabling interconnected theories recognizes the complexity of the migration and integration processes in a way that encourages us to look in new places for new connections and mechanisms that are disrupting and transforming migration and integration processes. It explicitly acknowledges that although health professionals are rational agents, their agency is structured by the different degrees of mobility they have access to and integration pathways. It also encourages us to undertake research in ways that do not ignore these new connections, thus avoiding the situation where our scholarship has less and less relevance to what is happening on the ground. It is meant to be a framework within which to situate one’s analysis and to acknowledge that there are other relevant levels that should not be ignored but that may not necessarily be the focus of one’s analysis. The next challenge is to develop a sound methodology to capture the impact of these complex migration and integration processes. Another possible direction is to develop typologies to help to analyse the uneven distribution of mobility capital among professionals from different countries and different professions.

References

Abbott, A. D. (1988) The System of Professions: An Essay on the Division of Expert Labor. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Adhikari, R. (2013) ‘Empowered wives and frustrated husbands: Nursing, gender and migrant Nepali in the UK’. International Migration 51(6), pp. 168–179.

Ahmad, A., Amuah, E., Mehta, N., Nkala, B. and Singh, J. A. (2003) ‘The ethics of nurse poaching from the developing world’. Nursing Ethics 10(6), pp. 667–670.

Aiken, L. H., Buchan, J., Sochalski, J., Nichols, B. and Powell, M. (2004) ‘Trends in international nurse migration’. Health Affairs 23(3), pp. 69–77.

Alexis, O. and Vydelingum, V. (2004) ‘The lived experience of overseas black and minority ethnic nurses in the NHS in the South of England’. Diversity in Health and Social Care 1(1), pp. 13–20.

Allan, H. T., Larsen, J. A., Bryan, K. and Smith, P. (2004) ‘The social reproduction of institutional racism: Internationally recruited nurses’ experiences of the British health services’. Diversity in Health and Social Care 1(2), pp. 117–125.

Anthias, Floya (2012) ‘Transnational mobilities, migration research and intersectionality’. Nordic Journal of Migration Research 2(2), pp. 102–110.

Bach, S. (2003) International Migration of Health Workers: Labour and Social Issues. Paper prepared for the Sectoral Activities Department, International Labour Office, July.

Behnke, A., Taylor, B. A. and Parra-Cardona, J. R. (2008) ‘“I hardly understand English, but”: Mexican-origin fathers describe their commitment as fathers despite the challenges of immigration’. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 39, pp. 187–205.

Bernstein, J. and Shuval, J. T. (1998) ‘The occupational integration of former Soviet physicians in Israel’. Social Science & Medicine 47(6), pp. 809–819.

Bhambra, Gurminder K. (2014) Connected Sociologies. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Bourgeault, I. L. (2007) ‘Brain drain, brain gain and brain waste: Programs aimed at integrating and retaining the best and the brightest in health care’. Canadian Issues/Thémes Canadiens, pp. 96–99.

Bourgeault, I. L. (2015) ‘The double isolation of immigrants undertaking older adult care work’. In C. Stacey and M. Duffy (eds) Caring on the Clock. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, pp. 117–125.

Bourgeault, I. L. and Wrede, S. (2011) ‘Caring across borders: Contrasting the contexts of nurse migration in Canada and Finland’. In C. Benoit and H. Hallgrimsdottir (eds) Valuing Care Work: Comparative Perspectives. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 65–86.

Bourgeault, I. L., Neiterman, E., LeBrun, J., Viers, K. and Winkup, J. (2010) Brain Gain, Drain and Waste: The Experiences of IEHPs in Canada. Available for download: www.healthworkermigration.com (last accessed 28 January 2016).

Bourgeault, I. L., Labonté, R., Packer, C., Runnels V. and Tomblin Murphy, G. (forthcoming) ‘Knowledge and potential impact of the WHO Global Code of Practice on the international recruitment of health personnel: Does it matter for source and destination country stakeholders?’. Human Resources for Health.

Buchan, J. (2004) ‘International rescue? The dynamics and policy implications of the international recruitment of nurses to the UK’. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 9(1), pp. 10–16.

Byron, M. (1998) ‘Migration, work, and gender: The case of post-war labour migration from the Caribbean to Britain’. In M. Chamberlain (ed.) Caribbean Migration: Globalised Identities. London: Routledge, pp. 226–242.

Calavita, K. (2006) ‘Gender, migration, and law: Crossing borders and bridging disciplines’. International Migration Review 40(1), pp. 104–132.

Camlin, C. S., Snow, R. C., and Hosegood, V. (2014). ‘Gendered patterns of migration in rural South Africa’. Population, Space and Place 20(6), pp. 528–551.

Castles, S. and Miller, M. J. (2003) The Age of Migration (3rd edn). New York & London: The Guilford Press.

Choy, C. (2003) Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Collinds, E. M. (2004) Career Mobility among Immigrant Registered Nurses in Canada: Experiences of Caribbean Women. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Connell, J. (2008) ‘Niue: embracing a culture of migration’. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34(6), pp. 1021–1040.

Dahle, Rannveig and Seeberg, Marie Louise (2013) ‘“Does she speak Norwegian?” Ethnic dimensions of hierarchy in Norwegian health care workplaces’. Nordic Journal of Migration Research 3(2), pp. 82–90.

Diallo, K. (2004) ‘Data on the migration of health-care workers: Sources, uses and challenges’, Bulletin of the World Health Organization 82(8), pp. 601–607. www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/82/8/en/601.pdf (last accessed 28 January 2016).

Dicicco-Bloom, B. (2004) ‘The racial and gendered experiences of immigrant nurses from Kerala, India’. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 15(1), pp. 26–33.

Eckenwiler, L. (2014) ‘Care worker migration, global health equity, and ethical place-making’. Women’s Studies International Forum 47, pp. 213–222.

European Commission (2013) Modernisation of the Professional Qualifications Directive: Frequently Asked Questions. Memo Brussels, 9 October 2013. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-13-867_en.htm (last accessed 1 July 2015).

Factourovich, A., Ritsner, M., Maoz, B., Levin, K., Mirsky, J., Ginath, Y., Segal, A. and Natan, E. B. (1996) ‘Psychological adjustment among Soviet immigrant physicians: Distress and self-assessments of its sources’. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences 33(1), pp. 32–39.

George, S. (2005) When Women Come First: Gender and Class in Transnational Migration. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Giri, N. M. (1998) ‘South Asian women physicians’ working experiences in Canada’. Canadian Woman Studies 18(1), pp. 61–64.

Groutsis, D. (2003) ‘The state, immigration policy and labour market practices: The case of overseas-trained doctors’. The Journal of Industrial Relations 45(1), pp. 67–86.

Guarnizo, L. E. (2003) ‘The economics of transnational living’. International Migration Review 37(3), pp. 666–699.

de Haas, H. (2010) ‘Migration and development: A theoretical review’. International Migration Review 44(1), pp. 227–264.

Hagey, R., Choudhry, U., Guruge, S., Turrittin, J., Collins, E. and Lee, R. (2001) ‘Immigrant Nurses’ Experiences of Racism’. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 33(4), pp. 389–394.

Hagopian, A., Ofosu, A., Fatusi, A., Biritwum, R., Essel, A., Hart, L. G. and Watts, C. (2005) ‘The flight of physicians from West Africa: Views of African physicians and implications for policy’. Social Science & Medicine 61(8), pp. 1750–1760.

Hankivsky, O., Reid, C., Cormier, R., Varcoe, C., Clark, N., Benoit, C. and Brotman, S. (2010) ‘Exploring the promises of intersectionality for advancing women’s health research’. International Journal for Equity in Health 9(5), pp. 1–15.

Harris, J. R. and Todaro, M. P. (1970) ‘Migration, unemployment and development: A two-sector analysis’. The American Economic Review 60(1), pp. 126–142.

Hazarika, I. (2015) Flight of International Medical Graduates: A Cross-Country Comparative Study Examining Key Events in the Trajectory. PhD thesis, University of Melbourne.

Hochschild, A. R. (2000) ‘Global care chains and emotional surplus value’. In W. Hutton and A. Giddens (eds) On The Edge: Living with Global Capitalism. London: Jonathan Cape.

Isaksen, L. W. (2010) ‘Transnational care: The social dimensions of international nurse recruitment’. In L. W. Isaksen (ed.) Global Care Work: Gender and Migration in Nordic Societies. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, pp. 137–157.

Jeans, M. E. (2006) ‘In-country challenges to addressing the effects of emerging global nurse migration on health care delivery’. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 7(3), pp. 58S–61S.

Kapur, D. and McHale, J. (2005) Give Us Your Best and Brightest: The Global Hunt for Talent and Its Impact on the Developing World. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Kaufmann V. and Montulet B. (2008) ‘Between social and spatial mobilities: The issue of social fluidity’. In W. Canzler, V. Kaufmann and S. Kesselring (eds) Tracing Mobilities: Towards a Cosmopolitan Perspective. Farnham and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, pp. 37–56.

Kaufmann V., Bergman M. and Joye D. (2004) ‘Motility: Mobility as capital’. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28(4), pp. 745–756.

Kingma, M. (2006). Nurses on the Move: Migration and the Global Health Care Economy. Ithaca, NY and London: ILR Press.

Labonté R., Packer C. and Klassen N. (2006) ‘Managing health professional migration from sub-Saharan Africa to Canada: A stakeholder inquiry into policy options’. Human Resources for Health, 4(22). Available online: www.human-resources-health.com/content/4/1/22 (last accessed 28 January 2016).

Larsen, J. A. (2007) ‘Embodiment of discrimination and overseas nurses’ career progression’. Journal of Clinical Nursing 16(12), pp. 2187–2195.

Laurén, J. and Wrede, S. (2008) ‘Immigrants in care work: ethnic hierarchies and work distribution’. Finnish Journal of Ethnicity and Migration 3(3), pp. 20–31.

Lee, E. S. (1966) ‘A theory of migration’. Demography 3(1), pp. 47–57.

Levitt, P. (2001) ‘Transnational migration: Taking stock and future directions’. Global Networks 1(3), pp. 195–216.

Levitt, P. and Jaworsky, B. N. (2007) ‘Transnational migration studies: Past developments and future trends’. Annual Review of Sociology 33, pp. 129–156.

McNeil-Walsh, C. (2004) ‘Widening the discourse: A case for the use of post-colonial theory in the analysis of South African nurse migration to Britain’. Feminist Review 77, pp. 120–124.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A. and Taylor, J. E. (1993) ‘Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal’. Population and Development Review 19(3), pp. 431–466.

Neiterman, E. and Bourgeault, I. L. (2011) ‘Conceptualizing professional diaspora: international medical graduates in Canada’. Journal of International Migration and Integration 12(3), pp. 39–57.

Neiterman, E. and Bourgeault, I. L. (2015a) ‘Professional integration as a process of professional resocialization: Internationally educated health professionals in Canada’. Social Science & Medicine 131, pp. 74–81.

Neiterman, E. and Bourgeault, I. L. (2015b) ‘The shield of professional status: Comparing discriminatory experiences of IENs and IMGs in Canada’. Health 19(6), pp. 615–634.

Neiterman, E., Salmonsson, L. and Bourgeault, I. L. (2015) ‘Navigating through otherness and belonging: A comparative case study of international medical graduates professional integration in Canada and Sweden’. Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 15(4), pp. 773–795.

NHS (Department of Health, UK) (2001) Code of Practice for NHS Employers Involved in the International Recruitment of Healthcare Professionals. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4006781 (last accessed 28 January 2016).

OECD (2007) ‘Immigrant health workers in OECD countries in the broader context of highly skilled migration’. International Migration Outlook. www.oecd.org/els/mig/41515701.pdf (last accessed 28 January 2016).

Orum, A. M. (2005) ‘Circles of influence and chains of command: The social processes whereby ethnic communities influence host societies’. Social Forces 84(2), pp. 921–939.

Orzack, L. (1998) ‘Professions and world trade diplomacy: National systems and international authority’. In V. Olgiati, L. Orzack and M. Saks (eds) Professions, Identity, and Order in Comparative Perspective. Onati: Institute for International Study of the Sociology of Law.

Parkin, F. (1979) Marxism and Class Theory: A Bourgeois Critique. New York: Columbia University Press.

Pittman, P. M., Folsom, A. J. and Bass, E. (2010) ‘US-based recruitment of foreign-educated nurses: Implications of an emerging industry’. American Journal of Nursing 110(6), pp. 38–48.

Remennick, L. I. and Ottenstein-Eisen, N. (1998) ‘Reaction of new Soviet immigrants to primary health services in Canada’. International Journal of Health Services 28(3), pp. 555–574.

Robinson, V. and Carey, M. (2000). ‘Skilled international migration: Indian doctors in the UK’. International Migration 38(10), pp. 89–108.

Ryan, J. (2002) ‘Chinese women as transnational migrants: Gender and class in global migration narratives’. International Migration 40(2), pp. 93–116.

Ryan, L. (2008) ‘“I had a sister in England”: Family-led migration, social networks and nurses’. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34(3), pp. 453–470.

Salmonsson, L. (2014) The ‘Other’ Doctor: Boundary Work within the Swedish Medical Profession. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Uppsala University.

Sassen, S. (1988) The Mobility of Capital and Labor: A Study in International Investment and Labor Flow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sassen, S. (1998) Globalization and Its Discontents: Essays on the New Mobility of People and Money. New York: The New Press.

Sassen, S. (2002) Global Networks, Linked Cities. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

Sassen, S. (2007) A Sociology of Globalization. New York: W.W. Norton.

Shuval, J. (1995) ‘Elitism and professional control in a saturated market: Immigrant physicians in Israel’. Sociology of Health and Illness 17(4), pp. 330–365.

Shuval, J. (1998) ‘Credentialling immigrant physicians in Israel’. Health & Place 4(4), pp. 375–381.

Shuval, J. (2000) ‘The reconstruction of professional identity among immigrant physicians in three societies’. Journal of Immigrant Health 2(4), pp. 191–102.

Squires, A. (2011) ‘The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and Mexican nursing’. Health Policy and Planning 26, pp. 124–132.

Stouffer, S. A. (1940) ‘Intervening opportunities: A theory relating mobility and distance’. American Sociological Review 5(6), pp. 845–867.

Tankwanchi A., Vermund S.H. and Perkins D.D. (2014) ‘Has the WHO global code of practice on the international recruitment of health personnel been effective?’. The Lancet Global Health 2(7), pp. e390–e391.

Turrittin, J., Hagey, R., Guruge, S., Collins, E. and Mitchell, M. (2002) ‘The experiences of professional nurses who have migrated to Canada: Cosmopolitan citizenship or democratic racism?’. International Journal of Nursing Studies 39, pp. 655–667.

Waldinger, R., Lim, N. and Cort, D. (2007) ‘Bad jobs, good jobs, no jobs? The employment experience of the Mexican American second generation’. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33(1), pp. 1–35.

Wallerstein, I. (1974) The Modern World System I, Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York: Academic Press.

Walton-Roberts, M. (2015) ‘International migration of health professionals and the marketization and privatization of health education in India: From push-pull to global political economy’. Social Science & Medicine 124, pp. 374–382.

WHO (2006) Working Together for Health. World Health Report. Geneva: World Health Organization.

WHO (2010) Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Witz, A. (1992) Professions and Patriarchy. London: Routledge.

Wrede, Sirpa (2010) ‘Nursing: Globalization of a female-gendered profession’. In E. Kuhlmann and E. Annandale (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Gender and Healthcare. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 437–453.

Yeates, N. (2004) ‘Broadening the scope of global care chain analysis: Nurse migration in the Irish context’, Feminist Review, 77, pp. 79–95.

Yeates, Nicola (2009) Globalizing Care Economies and Migrant Workers: Explorations in Global Care Chains. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.