Firstly, tear out the Test 1 Listening / Reading Answer Sheet at the back of this book.

The recordings of the Listening test last for about 20 minutes. There are four separate recordings, called sections. There are ten questions to answer in each section, totalling 40. Except for an example at the beginning of Section 1, everything is played once only.

Write your answers on the pages below as you listen. After Section 4 has finished, you have ten minutes to transfer your answers to your Listening Answer Sheet. You will need to time yourself for this transfer, but in an IELTS exam, a recorded voice gives you the time.

Each question in the Listening test is worth one mark, and a band from 1-9 is calculated from the mark out of 40.

After checking your answers on pp 57-61, go to page 9 for the raw-score conversion table.

PLAY RECORDING #1.

PLAY RECORDING #1.

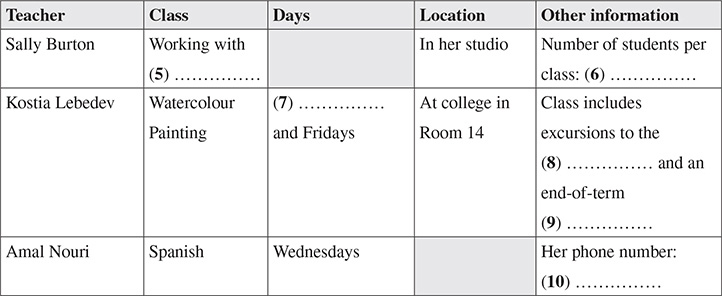

SECTION 1 Questions 1-10

COMMUNITY COLLEGE CLASSES

Questions 1-4

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

Example What does the woman, Amal Nouri, teach?

A Arabic

B Spanish √

C Korean

1 What is the principal doing at the end of the term?

A Starting another job

B Going to Spain

C Retiring

2 According to the receptionist, from whom is feedback most important for new teachers?

A Their students

B The principal

C Other teachers

3 What do a lot of people do who take an evening class?

A Make new friends there

B Not finish the course

C Find better jobs afterwards

4 What percentage of students’ fees do teachers pay for most classes they enroll in at the college?

A 70

B 50

C 10

HOW TO GET A SEVEN

Complete the table below.

Write ONE WORD OR A NUMBER for each answer.

PLAY RECORDING #2.

PLAY RECORDING #2.

SECTION 2 Questions 11-20

VOLUNTARY GUIDING

Questions 11-14

Choose FOUR answers from the box, below, and write the correct letter, A-F, next to questions 11-14 below.

A Eliezer Montefiore

B Grace Cossington-Smith

C Paul Cézanne

D Arthur Boyd

E Wendy McEwen

F A voluntary guide

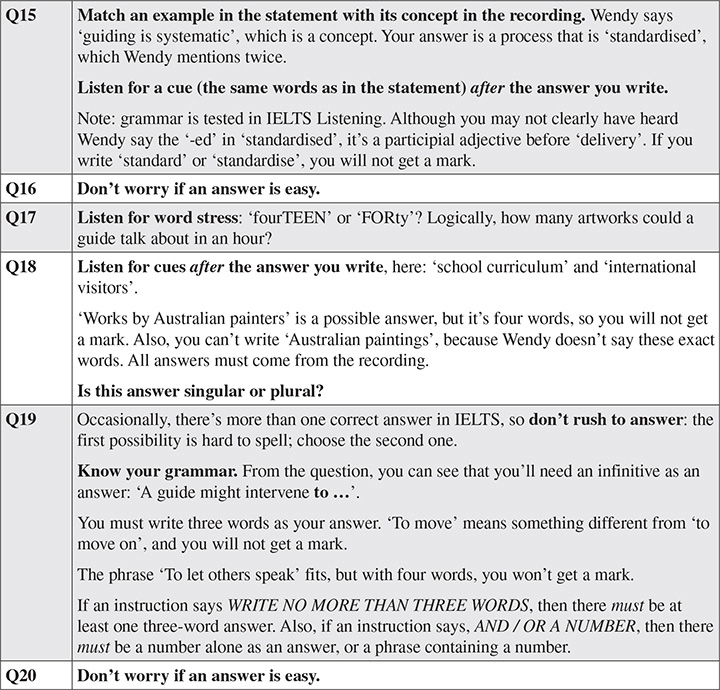

Answer the questions below.

Write NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER for each answer.

15 What is the process of giving the same information about the same artworks?

………………..………………..

16 How long is each guided tour?

………………..………………..

17 About how many artworks do guides discuss in a tour?

………………..………………..

18 What do schoolchildren and international visitors expect to see at the gallery?

………………..………………..

19 When a member of the public is talking about an artwork, why might a guide intervene?

………………..………………..

20 Which language do two of the new volunteers speak?

………………..………………..

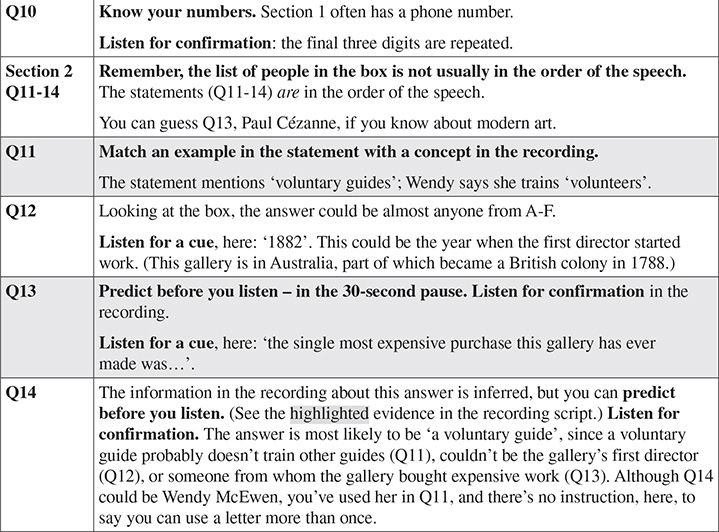

HOW TO GET A SEVEN

Below are tips for some but not all questions (#26-27).

SECTION 3 Questions 21-30

PREPARING FOR A SCHOLARSHIP INTERVIEW

Questions 21-24

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

21 The woman, Sovy, would like to study

A History.

B Development.

C Tourism.

22 Sovy works as

A a volunteer.

B a librarian.

C a Russian teacher.

23 Sovy has

A a BA only.

B a BA and part of an MA.

C a BA and an MA.

24 Sovy thinks the scholarship selectors

A favour people from big cities.

B favour people from the provinces.

C award scholarships all around the country.

Questions 25-27

Complete the sentences below.

Write ONE WORD ONLY for each answer.

25 Sovy feels………………..of her background.

26 Sovy doubts the selectors would be interested in her……………….. .

27 Sovy thinks showing her passion for………………..might help during her interview.

Choose THREE letters: A-F.

Which THREE relate to Vibol?

A He is single.

B He opened a restaurant.

C He travelled around Australia.

D He studied in Adelaide.

E He did a Master’s in International Law.

F He wants an easy life.

HOW TO GET A SEVEN

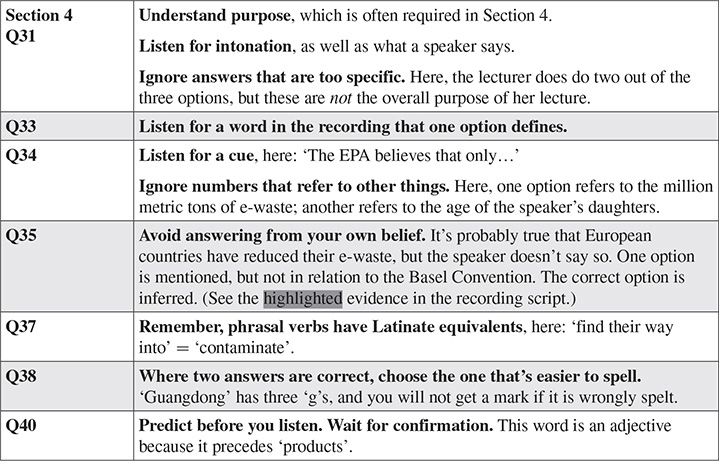

SECTION 4 Questions 31-40

E-WASTE DISPOSAL

Questions 31-35

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

31 What is the purpose of the lecture?

A To get students to recycle smartphones

B To let students know more about e-waste

C To encourage students to develop an app

32 The lecturer talks about her family’s behaviour because it is

A typical.

B exceptional.

C ideal.

33 According to the lecturer, an e-waste recycler in the US receives a……amount of cash.

A very small

B small

C moderate

34 According to the EPA, only…… of e-waste sent for recycling is actually recycled.

A 8%

B 13%

C 20%

35 European countries signed the Basel Convention,

A and greatly reduced their e-waste.

B but still send e-waste abroad illegally.

C so local recyclers have enough e-waste to process.

Questions 36-40

Complete the sentences below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS OR A NUMBER for each answer.

36 An average smartphone has about………………..different chemical elements inside.

37 Toxins from burnt electronic devices find their way into the……………….. .

38 Currently, the city of Guiyu, in……………….., deals with the most e-waste.

39 The EPA predicts that by………………., global e-waste will reach 100 million metric tons a year.

40 Only a tiny amount of recycled e-waste is used to make more………………..products.

HOW TO GET A SEVEN

Firstly, turn over the Test 1 Listening Answer Sheet that you used earlier.

The Reading test lasts exactly 60 minutes. There are three passages to read, and 40 questions to answer in total. There are no examples.

Certainly, make any marks on the pages below, but transfer your answers to the answer sheet as you read since there is no extra time at the end to do so.

Each question in the Reading test is worth one mark, and a band from 1-9 is calculated from the mark out of 40.

After checking your answers on pp 64-66, go to page 9 for the raw-score conversion table.

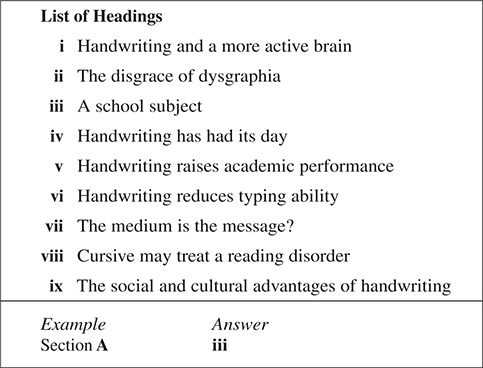

PASSAGE 1

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-14, based on Passage 1.

Questions 1-5

Passage 1 on the following page has six sections: A-F.

Choose the correct heading for sections B-F from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number, i-ix, in boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet.

1 Section B

2 Section C

3 Section D

4 Section E

5 Section F

A ‘When I was in school in the 1970s,’ says Tammy Chou, ‘my end-of-term report included Handwriting as a subject alongside Mathematics and Physical Education, yet, by the time my brother started, a decade later, it had been subsumed into English. I learnt two scripts: printing and cursive,* while Chris can only print.’

The 2013 Common Core, a curriculum used throughout most of the US, requires the tuition of legible writing (generally printing) only in the first two years of school; thereafter, teaching keyboard skills is a priority.

B ‘I work in recruitment,’ continues Chou. ‘Sure, these days, applicants submit a digital CV and cover letter, but there’s still information interviewees need to fill out by hand, and I still judge them by the neatness of their writing when they do so. Plus there’s nothing more disheartening than receiving a birthday greeting or a condolence card with a scrawled message.’

C Psychologists and neuroscientists may concur with Chou for different reasons. They believe children learn to read faster when they start to write by hand, and they generate new ideas and retain information better. Karin James conducted an experiment at Indiana University in the US in which children who had not learnt to read were shown a letter on a card and asked to reproduce it by tracing, by drawing it on another piece of paper, or by typing it on a keyboard. Then, their brains were scanned while viewing the original image again. Children who had produced the freehand letter showed increased neural activity in the left fusiform gyrus, the inferior frontal gyrus, and the posterior parietal cortex – areas activated when adults read or write, whereas all other children displayed significantly weaker activation of the same areas.

James speculates that in handwriting there is variation in the production of any letter, so the brain has to learn each personal font – each variant of ‘F’, for example, that is still ‘F’. Recognition of variation may establish the eventual representation more permanently than recognising a uniform letter printed by computer.

Victoria Berninger at the University of Washington studied children in the first two grades of school to demonstrate that printing, cursive, and keyboarding are associated with separate brain patterns. Furthermore, children who wrote by hand did so much faster than the typists, who had not been taught to touch type. Not only did the typists produce fewer words but also the quality of their ideas was consistently lower. Scans from the older children’s brains exhibited enhanced neural activity when their handwriting was neater than average, and, importantly, the parts of their brains activated are those crucial to working memory.

Pam Mueller and Daniel Oppenheimer have shown in laboratories and live classrooms that tertiary students learn better when they take notes by hand rather than inputting via keyboard. As a result, some institutions ban laptops and tablets in lectures, and prohibit smartphone photography of lecture notes. Mueller and Oppenheimer also believe handwriting aids contemplation as well as memory storage.

D Some learners of English whose native script is not the Roman alphabet have difficulty in forming several English letters: the lower case ‘b’ and ‘d’, ‘p’ and ‘q’, ‘n’ and ‘u’, ‘m’ and ‘w’ may be confused. This condition affects a tiny minority of first-language learners and sufferers of brain damage. Called dysgraphia, it appears less frequently when writers use cursive instead of printing, which is why cursive has been posited as a cure for dyslexia.

E Berninger is of the opinion that cursive, endangered in American schools, promotes self-control, which printing may not, and which typing – especially with the ‘delete’ function – unequivocally does not. In a world saturated with texting, where many have observed that people are losing the ability to filter their thoughts, a little more restraint would be a good thing.

A rare-book and manuscript librarian, Valerie Hotchkiss, worries about the cost to our heritage as knowledge of cursive fades. Her library contains archives from the literary giants Mark Twain, Marcel Proust, HG Wells, and others. If the young generation does not learn cursive, its ability to decipher older documents may be compromised, and culture lost.

F Paul Bloom, from Yale University, is less convinced about the long-term benefits of handwriting. In the 1950s – indeed in Tammy Chou’s idyllic 1970s – when children spent hours practising their copperplate, what were they doing with it? Mainly copying mindlessly. For Bloom, education, in the complex digital age, has moved on.

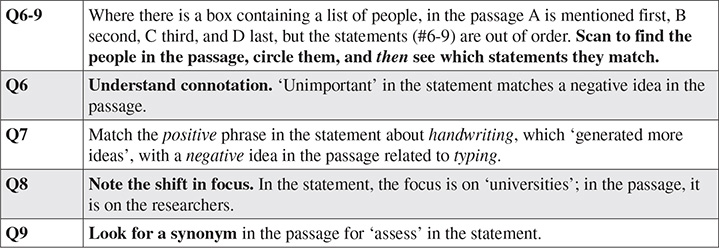

Questions 6-9

Look at the following statements and list of people below.

Match each statement with the correct person: A, B, C, or D.

Write the correct letter, A, B, C, or D, in boxes 6-9 on your answer sheet.

6 According to him / her / them, education is now very sophisticated, so handwriting is unimportant.

7 He / She / They found children who wrote by hand generated more ideas.

8 Universities have stopped students using electronic devices in class due to his / her / their research.

9 He / She / They may assess character by handwriting.

List of people

A Tammy Chou

B Victoria Berninger

C Paul Mueller and Daniel Oppenheimer

D Paul Bloom

Complete the summary using the list of words, A-H, below.

Write the correct letter, A-H, in boxes 10-14 on your answer sheet.

Educators in the US have decided that handwriting is no longer worth much curriculum time. Printing, not cursive, is usually taught. Some (10)……………….. and neuroscientists (11)……………….. this decision as there seems to be a(n) (12)……………….. between early reading and handwriting. Children with the best handwriting produce the most neural activity and the most interesting schoolwork. (13)……………….. of cursive consider it more useful than printing. However, not all academics believe in the necessity of handwriting. In the digital world, perhaps keyboarding is (14)……………….. .

PASSAGE 2

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 15-27, based on Passage 2 below.

Growing up in New Zealand

It has long been known that the first one thousand days of life are the most critical in ensuring a person’s healthy future; precisely what happens during this period to any individual has been less well documented. To allocate resources appropriately, public health and education policies need to be based upon quantifiable data, so the New Zealand Ministry of Social Development began a longitudinal study of these early days, with the view to extending it for two decades. Born between March 2009 and May 2010, the 6,846 babies recruited came from a densely populated area of New Zealand, and it is hoped they will be followed until they reach the age of 21.

By 2014, four reports, collectively known as Growing Up in New Zealand (GUiNZ), had been published, showing New Zealand to be a complex, changing country, with the participants and their families’ being markedly different from those of previous generations.

Of the 6,846 babies, the majority were identified as European New Zealanders, but one quarter were Maori (indigenous New Zealanders), 20% were Pacific (originating in islands in the Pacific), and one in six were Asian. Almost 50% of the children had more than one ethnicity.

The first three reports of GUiNZ are descriptive, portraying the cohort before birth, at nine months, and at two years of age. Already, the first report, Before we are born, has made history as it contains interviews with the children’s mothers and fathers. The fourth report, which is more analytical, explores the definition of vulnerability for children in their first one thousand days.

Before we are born, published in 2010, describes the hopes, dreams, and realities that prospective parents have. It shows that the average age of both parents having a child was 30, and around two-thirds of parents were in legally binding relationships. However, one third of the children were born to either a mother or a father who did not grow up in New Zealand – a significant difference from previous longitudinal studies in which a vast majority of parents were New Zealanders born and bred. Around 60% of the births in the cohort were planned, and most families hoped to have two or three children. During pregnancy, some women changed their behaviour, with regard to smoking, alcohol, and exercise, but many did not. Such information will be useful for public health campaigns.

Now we are born is the second report. Fifty-two percent of its babies were male and 48% female, with nearly a quarter delivered by caesarean section. The World Health Organisation and New Zealand guidelines recommend babies be breastfed exclusively for six months, but the median age for this in the GUiNZ cohort was four months, since almost one third of mothers had returned to full-time work. By nine months, the babies were all eating solid food. While 54% of them were living in accommodation their families owned, their parents had almost all experienced a drop in income, sometimes a steep one, mostly due to mothers’ not working. Over 90% of the babies were immunised, and almost all were in very good health. Of the mothers, however, 11% had experienced post-natal depression – an alarming statistic, perhaps, but, once again, useful for mental health campaigns. Many of the babies were put in childcare while their mothers worked or studied, and the providers varied by ethnicity: children who were Maori or Pacific were more likely to be looked after by grandparents; European New Zealanders tended to be sent to day care.

Now we are two, the third report, provides more insights into the children’s development – physically, emotionally, behaviourally, and cognitively. Major changes in home environments are documented, like the socio-economic situation, and childcare arrangements. Information was collected both from direct observations of the children and from parental interviews. Once again, a high proportion of New Zealand two-year-olds were in very good health. Two thirds of the children knew their gender, and used their own name or expressed independence in some way. The most common first word was a variation on ‘Mum’, and the most common favourite first food was a banana. Bilingual or multi-lingual children were in a large minority of 40%. Digital exposure was high: one in seven two-year-olds had used a laptop or a children’s computer, and 80% watched TV or DVDs daily; by contrast, 66% had books read to them each day.

The fourth report evaluates twelve environmental risk factors that increase the likelihood of poor developmental outcomes for children, and draws on experiences in Western Europe, where the specific factors were collated. This, however, was the first time for their use in a New Zealand context. The factors include: being born to an adolescent mother; having one or both parents on income-tested benefits; and, living in cramped conditions.

In addition to descriptive ones, future reports will focus on children who move in and out of vulnerability to see how these transitions affect their later life.

To date, GUiNZ has been highly successful with only a very small dropout rate for participants – even those living abroad, predominantly in Australia, have continued to provide information. The portrait GUiNZ paints of a country and its people is indeed revealing.

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 2?

In boxes 15-20 on your answer sheet, write:

15 Findings from studies like GUiNZ will inform public policy.

16 Exactly 6,846 babies formed the GUiNZ cohort.

17 GUiNZ will probably end when the children reach ten.

18 Eventually, there will be 21 reports in GUiNZ.

19 So far, GUiNZ has shown New Zealanders today to be rather similar to those of 25 years ago.

20 Parents who took part in GUiNZ believe New Zealand is a good place to raise children.

Questions 21-27

Classify the following things that relate to:

A Report 1.

B Report 2.

C Report 3.

D Report 4.

Write the correct letter, A, B, C, or D, in boxes 21-27 on your answer sheet.

21 This is unique because it contains interviews with both parents.

22 This looks at how children might be at risk.

23 This suggests having a child may lead to financial hardship.

24 Information for this came from direct observations of children.

25 This shows many children use electronic devices.

26 This was modelled on criteria used in Western Europe.

27 This suggests having a teenage mother could negatively affect a child.

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 28-40, based on Passage 3 below.

LET THERE BE LIGHT?

A ‘Incandescent light bulbs lit the 20th century; the 21st will be lit by LED lamps.’ So stated the Nobel Prize Committee on awarding the 2014 prize for physics to the inventors of light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

Around the world, LED systems are replacing most kinds of conventional lighting since they use about half the electricity, and the US Department of Energy expects LEDs to account for 74% of US lighting sales by 2030.

However, with lower running costs, LEDs may be left on longer, or installed in places that were previously unlit. Historically, when there has been an improvement in lighting technology, far more outdoor illumination has occurred. Furthermore, many LEDs are brighter than other lights, and they produce a blue-wavelength light that animals misinterpret as dawn.

According to the American Medical Association, there has been a noticeable rise in obesity, diabetes, cancer, and cardio-vascular disease in people like shift workers exposed to too much artificial light of any kind. It is likely more pervasive LEDs will contribute to a further rise.

B In some cities, a brown haze of industrial pollution prevents enjoyment of the night sky; in others, a yellow haze from lighting has the same effect, and it is thought that almost 70% of people can no longer see the Milky Way.

When a small earthquake disabled power plants in Los Angeles a few years ago, the director of the Griffith Observatory was bombarded with phone calls by locals who reported an unusual phenomenon they thought was caused by the quake – a brilliantly illuminated night sky, in which around 7,000 stars were visible. In fact, this was just an ordinary starry night, seldom seen in LA due to light pollution!

Certainly, light pollution makes professional astronomy difficult, but it also endangers humans’ age-old connection to the stars. It is conceivable that children who do not experience a true starry night may not speculate about the universe, nor may they learn about nocturnal creatures.

C Excessive illumination impacts upon the nocturnal world. Around 30% of vertebrates and over 60% of invertebrates are nocturnal; many of the remainder are crepuscular – most active at dawn and dusk. Night lighting, hundreds of thousands of times greater than its natural level, has drastically reduced insect, bird, bat, lizard, frog, turtle, and fish life, with even dairy cows producing less milk in brightly-lit sheds.

Night lighting has a vacuum-cleaner effect on insects, particularly moths, drawing them from as far away as 122 metres. As insects play an important role in pollination, and in providing food for birds, their destruction is a grave concern. Using low-pressure sodium-vapour lamps or UV-filtered bulbs would reduce insect mortality, but an alternative light source does not help amphibians: frogs exposed to any night light experience altered feeding and mating behaviour, making them easy prey.

Furthermore, birds and insects use the sun, the moon, and the stars to navigate. It is estimated that around 500 million migratory birds are killed each year by collisions with brightly-lit structures, like skyscrapers or radio towers. In Toronto, Canada, the Fatal Light Awareness Program educates building owners about reducing such deaths by darkening their buildings at the peak of the migratory season. Still, over 1,500 birds may be killed within one night when this does not happen.

Non-migratory birds are also adversely affected by light pollution – sleep is difficult, and waking up only occurs when the sun has overpowered artificial lighting, resulting in the birds’ being too late to catch insects.

Leatherback turtles, which have lived on Earth for over 150 million years, are now endangered as their hatchlings are meant to follow light reflected from the moon and stars to go from their sandy nests to the sea. Instead, they follow street lamps or hotel lights, resulting in death by dehydration, predation, or accidents, since they wander onto the road in the opposite direction from the sea.

D Currently, eight percent of all energy generated in the US is dedicated to public outdoor lighting, and much evidence shows that lighting and energy use are growing at around four percent a year, exceeding population growth. In some newly-industrialised countries, lighting use is rising by 20%. Unfortunately, as the developing world urbanises, it also lights up brightly, rather than opting for sustainability.

E There are several organisations devoted to restoring the night sky: one is the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), based in Arizona, US. The IDA draws attention to the hazards of light pollution, and works with manufacturers, planners, legislators, and citizens to encourage lighting only what is necessary when necessary.

With 58 chapters in sixteen countries, the IDA has been the driving force behind the establishment of nine world reserves, most recently the 1,720-square-kilometre Rhon Biosphere Reserve in Germany. IDA campaigns have also reduced street lighting in several US states, and changed national legislation in Italy.

F Except in some parks and observatory zones, the IDA does not defend complete darkness, acknowledging that urban areas operate around the clock. For transport, lighting is particularly important. Nonetheless, there is an appreciable difference between harsh, glaring lights and those that illuminate the ground without streaming into the sky. The US Department of Transportation recently conducted research into highway safety, and found that a highway lit well only at interchanges was as safe as one lit along its entire length. In addition, reflective signage and strategic white paint improved safety more than adding lights.

Research by the US Department of Justice showed that outdoor lighting may not deter crime. Its only real benefit is in citizens’ perceptions: lighting reduces the fear of crime, not crime itself. Indeed, bright lights may compromise safety, as they make victims and property more visible.

The IDA recommends that where streetlights stay on all night, they have a lower lumen rating, or are controlled with dimmers; and, that they point downwards, or are fitted with directional metal shields. For private dwellings, low-lumen nightlights should be activated only when motion is detected.

G It is not merely the firefly, the fruit bat, or the frog that suffers from light pollution – many human beings no longer experience falling stars or any but the brightest stars, nor consequently ponder their own place in the universe. Hopefully, prize-winning LED lights will be modified and used circumspectly to return to us all the splendour of the night sky.

Reading Passage 3 has seven sections, A-G.

Which section contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-G, in boxes 28-32 on your answer sheet.

28 A light-hearted example of ignorance about the night sky

29 An explanation of how lighting may not equate with safety

30 A description of the activities of the International Dark-sky Association

31 An example of baby animals affected by too much night light

32 A list of the possible drawbacks of new lighting technology

Questions 33-35

Complete the sentences below.

Choose ONE WORD OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 33-35 on your answer sheet.

33 Too much ……………….. light has led to a rise in serious illness.

34 Approximately ………………..% of humans are unable to see the Milky Way.

35 About ……………… million migratory birds die crashing into lit-up tall buildings each year.

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 3?

In boxes 36-39 on your answer sheet, write:

36 It is alarming that so many animals are killed by night lighting.

37 It is good that developing countries now have brighter lighting.

38 Italians need not worry about reduced street lighting.

39 Bright lights along the road are necessary for safe driving.

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

Write the correct letter in box 40 on your answer sheet.

According to the writer, how much night lighting should there be in relation to what there is?

A Much more

B A little more

C A little less

D Much less

The Writing test lasts for 60 minutes. It has two tasks. Task 2 is worth twice as much as Task 1. Although candidates are assessed on four criteria for each task, an overall band, from 1-9, is awarded.

Spend about 20 minutes on this task.

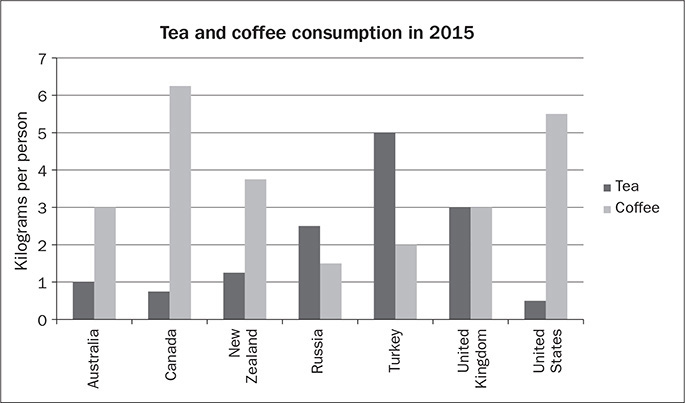

The chart below shows tea and coffee consumption in 2015.

Write a summary of the information. Select and report the main features, and make comparisons where necessary.

Write at least 150 words.

Spend about 40 minutes on this task.

Write about the following topic:

In some countries at secondary or high school, there may be two streams of study: academic or vocational.*

What are the advantages for students and society of putting students into two streams at the age of fifteen?

Provide reasons for your answer, including relevant examples from your own knowledge or experience.

Write at least 250 words.

The Speaking test lasts for eleven to fourteen minutes. There are three parts, and a candidate answers around 25 questions in total. An overall band from 1-9 is awarded by the Speaking examiner although he or she assesses the candidate on four individual criteria: Fluency and Coherence; Vocabulary Range and Accuracy; Grammatical Range and Accuracy; and, Pronunciation.

For four to five minutes, the examiner asks the candidate questions on familiar topics, such as where the candidate lives, and what he or she does. Then, the examiner asks questions on two topics of general interest.

How might you answer the following questions?

1 Could you tell me what you’re doing at the moment: are you working or studying?

2 What do you do in your job?

3 Do you like your job?

4 What do you remember about your first day in this job?

5 Now, let’s talk about taking photos. Do you mainly take photos with your phone, or do you use a camera?

6 Is there anything in particular you like to take photos of?

7 Typically, what do you do with your photos after you’ve taken them?

8 Would you like to take classes in photography?

9 Let’s move on to talk about parks. Do you go to any parks near where you live?

10 Do you prefer a park with designated areas for leisure activities, or one that has mostly open space?

PLAY RECORDING #5 TO HEAR PART ONE OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

PLAY RECORDING #5 TO HEAR PART ONE OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

The examiner gives the candidate a topic, which is often a recount of a personal experience. The candidate has one minute to think about this and may make notes. Then he or she should speak for two minutes. The examiner may ask one or two brief questions at the end.

How might you speak about the following topic for two minutes?

I’d like you to tell me about an embarrassing experience you have had with food.

* Where were you?

* What happened?

* How did you feel afterwards?

And, what did other people think about this event?

PLAY RECORDING #6 TO HEAR PART TWO OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

PLAY RECORDING #6 TO HEAR PART TWO OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

For four to five minutes, the topic from Part 2 is developed more generally. Questions the examiner asks the candidate become more abstract, and the candidate should be able to do the following:

1 agree or disagree

2 identify and describe

3 compare or contrast

4 explain or defend

5 give reasons for

6 suggest or outline

7 evaluate or assess

8 speculate, and

9 predict.

PLAY RECORDING #7 TO HEAR PART THREE OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

PLAY RECORDING #7 TO HEAR PART THREE OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

Which of the above did Carla do?

How might you answer the following questions?

1 First of all, natural versus processed food.

Do people these days eat enough natural food?

To what extent are food producers responsible for the health of consumers?

2 Now, let’s consider global food security.

There are predictions of serious global food insecurity within our lifetime. What do you think about these predictions, and what might be done to improve global food security?

Go to pp 65-67 for the recording scripts.

Section 1: 1. C; 2. A; 3. B; 4. C; 5. Wool; 6. 7/seven; 7. Tuesdays (must have an ‘s’ at the end); 8. river; 9. exhibition; 10. 0212 064 993. Section 2: 11. E; 12. A; 13. C; 14. F; 15. Standardised/Standardized delivery; 16. 1/One hour; 17. 14/Fourteen; 18. Iconic works; 19. To alter misconceptions // To move on; 20. Japanese. Section 3: 21. B; 22. A; 23. B; 24. A; 25. proud; 26. politics; 27. development; 28-30. BDF (in any order). Section 4: 31. B; 32. A; 33. A; 34. C; 35. B; 36. 60/sixty; 37. food chain; 38. China // Guangdong Province; 39. 2020; 40. electronic.

The highlighted text below is evidence for the answers above.

Narrator : Recording 1.

Practice Listening Test 1.

Section 1. Community College Classes.

You will hear a receptionist and a teacher talking about classes at a community college. Read the example.

Receptionist : Good evening. How may I help you?

Amal : My name’s Amal Nouri. I’m a new teacher.

Receptionist : Nice to meet you, Amal.

You’re teaching Arabic, aren’t you?

Amal : Spanish, actually. I’m from Argentina.

Narrator : The answer is ‘B’.

On this occasion only, the first part of the conversation is played twice.

Before you listen again, you have 30 seconds to read questions 1 to 4.

Receptionist : Good evening. How may I help you?

Amal : My name’s Amal Nouri. I’m a new teacher.

Receptionist : Nice to meet you, Amal.

You’re teaching Arabic, aren’t you?

Amal : Spanish, actually. I’m from Argentina. My relatives moved there a long time ago. You’d be surprised how big the Arab community is in Latin America.

Receptionist : But Spanish isn’t on tonight – it’s tomorrow, Wednesday.

Amal : I know. I just thought I’d introduce myself. When I came for my interview, I only met the principal.

Receptionist : Mr Andrews?

Amal : Yes, Trevor Andrews. I must say he made me feel welcome, especially since he speaks Spanish himself.

Receptionist : Trevor’s a lovely guy. We’re going to miss him when he leaves at the end of the term.

Amal : Oh, why’s he leaving? Has he found another job?

Receptionist : (1) No, he’s retiring. He wants to spend more time with his grandchildren.

Amal : Right. He did mention them to me.

Receptionist : Did Trevor also mention that he likes to sit in on new teachers’ classes – just for a few minutes?

Amal : Umm…

Receptionist : It’s the policy of the college that new teachers are observed either by Trevor or by the vice-principal. I’m sure it’s in your contract.

Amal : Probably.

Receptionist : Don’t worry, it’s all quite informal – you won’t need to submit a lesson plan. (2) In general, student feedback at the end of the term is taken more seriously.

Amal : I see.

Receptionist : One more piece of advice, Amal. (3) Don’t be upset about the fact that you’ll start the term with fifteen students, but end up with five. That’s just what happens with evening classes. People sign up for things without really knowing what’s involved, or something else comes up on that night. (3) The high dropout rate is no reflection on your teaching.

Amal : Thanks for the tip.

Anyway, the real reason I’m here, tonight, is that I’d like to enroll in a class. I saw in the contract that (4) teachers can take one class themselves, paying only 10% of tuition, which seems a pretty good deal.

Receptionist : Indeed. When I was teaching Keyboarding Skills, I did Korean and Car Maintenance.

However, for a few courses, like Life Drawing, where students have to pay for a model, or Cooking with Seafood, where the ingredients are expensive, I’m afraid teachers can’t pay only (4) 10% – they have to pay the full fee.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 5 to 10.

Receptionist : So, Amal, what would you like to do?

Amal : I’m interested in Sally Burton’s class called ‘Working with (5) Wool’. I read about her in the local paper.

Receptionist : Yes, she’s very popular.

Amal : She made those amazing sculptures near the Town Hall. I’d no idea that (5) wool could be used in such huge artworks. I’d always thought of it just in clothing or carpets.

Receptionist : Unfortunately, Sally’s class is full. You see, she holds it in her studio, so she only accepts (6) seven students. And, we’ve already had (6) seven enrollments. I could put you on the waiting list.

Amal : It’s all right. My second choice was Watercolour Painting on (7) Tuesdays and Fridays. Yikes! There’s a class tonight.

Receptionist : Kostia’s class is also popular, but someone’s just cancelled, so there is a place for you.

Amal : Great.

Receptionist : For the first few nights, he’s in Room 14, but later in the term, when it’s lighter in the evening, he takes his class on excursions to the (8) river. There were some gorgeous paintings of the (8) river in our end-of-term (9) exhibition last year.

Amal : Sounds good.

By the way, where will my class be, tomorrow?

Receptionist : I’m not sure yet. We’ve had to make a few changes, but I’ll give you a call or send you a text when I know.

Amal : OK.

Receptionist : Ah… I don’t think I’ve got your phone number.

Amal : (10) It’s 0212 064 993.

Receptionist : Double nine three or double five three?

Amal : Double nine three.

Receptionist : Thanks.

Lovely to meet you, Amal. I hope you’ll enjoy your time with us.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 1.

Narrator : Recording 2.

Section 2. Voluntary Guiding.

You will hear a woman talking to voluntary guides at an art gallery.

Before you listen, you have 30 seconds to read questions 11 to 14.

Wendy McEwen : Good morning. (11) I’m Wendy McEwen. Please call me Wendy. I train volunteers at the gallery, and it’s my great pleasure to meet you today.

To begin, I’d like to quote from a speech made in 1882 by (12) our first director, Eliezer Montefiore. He said, ‘The Australian public should be afforded every facility to avail themselves of the educational and civilising influence engendered by an exhibition of works, bought at the public expense.’ We now live in a world where the notion of civilisation is seldom discussed, so let me mention some of its synonyms: enlightenment, refinement, and conformity with the standards of a highly developed society. In my view, this is what the creation and enjoyment of art can do for the public – conform, refine, and enlighten.

The idea of civilisation may be unfashionable, but an interest in different civilisations has certainly grown. Australian art is well represented in our collection – we have some wonderful paintings by Grace Cossington-Smith and Arthur Boyd – but there are Asian and European works to rival those abroad. In fact, (13) the single most expensive purchase this gallery has ever made was a 16.2-million-dollar landscape, painted in 1888, by Paul Cézanne. Visitors will ask you for this figure, just as they’ll be curious about Cézanne’s career as a banker in France and his time with his lover in Tahiti. (14) Sometimes, it seems the public is more interested in trivia than in art, so it’s your job to inform about the techniques of production, the themes an artwork deals with, as well as the culture from which it came. Elevate cultural discourse rather than stoop to the level of the popular press. Bear in mind those words of Eliezer Montefiore.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the talk, you have 30 seconds to read questions 15 to 20.

Wendy McEwen : While guides are diverse, guiding is systematic. By this I mean, we adhere to (15) standardised delivery whether tours be for viewers on Saturday morning, for school groups, or for VIPs. (15) Standardised delivery means that guides give the public virtually the same information about the same artworks. Sure, we all have our personal styles, but the content needs to be the same. To that end, guides are tested on information before taking their first tour.

Guides also have to keep an eye on the clock. Guided tours last (16) one hour. Since the building is large, part of that time is taken up in walking as well as mentioning the location of toilets, fire exists, and drinking fountains. After recent additions, the gallery is twice the size it was in 2013. So, ask your group where they’d like to go first, then calculate how many artworks you can see on each level. Aim for a total of (17) fourteen in your (16) hour. In each room, there’s lots to see, but you’ll only be talking about one or two items. By all means, when people in your group want to know about a work not on your list, go to it, but be brief. For the (18) iconic works by Australian painters, you’ll need to take longer. Some of these (18) iconic works are part of the school curriculum, and many are known to international visitors, who come just to see them.

In the past, guides stood beside an artwork and gave a short speech. To a certain extent, that’s still what happens with an audio tour. However, we now try to involve the public. One technique is called elicitation: when a guide asks questions about an artwork to see what knowledge already exists among the visitors. That way, you don’t appear as the ultimate authority, and often visitors know considerably more than you. On that note, there will be times when you need to intervene: to let others in the group speak, (19) to alter misconceptions, or, simply, (19) to move on.

As I said earlier, before you’re let loose on the public, each voluntary guide is evaluated.

Oh, that reminds me, I recall from your applications that two of you are (20) Japanese speakers, so we’ll probably ask you to take around groups of Japanese.

Now, let’s go into the gallery itself.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 2.

Narrator : Recording 3.

Section 3. Preparing for a Scholarship Interview.

You will hear a woman who is going to be interviewed for a scholarship talking to a man who previously received one.

Before you listen, you have 30 seconds to read questions 21 to 27.

Sovy : Hi, Vibol. Thanks for coming.

Vibol : No problem, Sovy. I hope I can help.

When’s the interview?

Sovy : On Thursday.

Vibol : Which course do you want to do?

Sovy : (21) A Master’s in Development Studies.

Vibol : Whereabouts?

Sovy : In Australia – Melbourne, actually.

Vibol : Well, Melbourne’s a great place. I visited in my semester break.

Sovy : (28-30) But you studied in Adelaide, didn’t you?

Vibol : Yeah.

Sovy : Why Adelaide?

Vibol : I heard before I applied for the scholarship that most applicants want to go to Sydney or Melbourne, so by choosing Adelaide I thought I’d have a better chance.

Sovy : D’you think I should go to Adelaide? Or not do (21) Development Studies?

Vibol : I think the key is to choose a course you’re really interested in, no matter where it is.

Sovy : Why’s that?

Vibol : Because the workload is heavy. My Master’s was probably the most difficult thing I’ve done in my whole life.

Sovy : I see.

Anyway, I bet the interview panel asks the same questions every year. What did they ask you?

Vibol : Firstly, about why I wanted to go to Australia.

Sovy : What did you say?

Vibol : I told them I’d been there already, and I liked it.

Sovy : What else did the panel ask?

Vibol : About my undergraduate degree. About my job. About how a Master’s would improve my performance and the performance of my organisation.

Sovy : Where are you working now?

Vibol : Oh, and they asked about my family – whether I’d take my wife with me.

Sovy : Well, I’m single, and planning to stay that way.

As to the course’s helping me at work, you know I quit my regular job, working in the university library.

Vibol : Yeah, I heard that. What are you doing now?

Sovy : (22) I’m a volunteer at a rehabilitation centre.

Vibol : How ever do you survive, financially?

Sovy : I teach English at night, and I live cheaply.

Vibol : Good for you.

You could say an MA would improve your prospects of finding permanent work.

Sovy : (23) I wonder what the interview panel will think about my undergraduate degree. It’s in Russian and History. I studied Russian so I could get a scholarship to Russia for a Master’s degree, but I only lasted six months in Europe.

Vibol : If I were you, (23) I wouldn’t mention you already have an incomplete Master’s. I’d focus on the work you’re doing now. Use phrases like ‘grass roots activism’ and ‘capacity building’. The panel will love that.

Sovy : Oh?

I do worry about my background. My family comes from a village on the coast. (24) I seem to recall that most people who were awarded scholarships in the last three years came from big cities and were socially successful.

Vibol : In the past, that was true. Indeed, all the interviews were held here, in the capital, but this year, they’re also taking place in the provinces, so scholarships will go to a more diverse group of people.

I don’t think you should beg for assistance, Sovy, but you don’t need to hide your background either. Be (25) proud of it.

Sovy : I am (25) proud of it.

Vibol : After all, it means you can empathise with the people you volunteer for. However, when you come back with a Master’s degree, you’ll be able to mix with more influential people – I mean, politically influential. I’d emphasise that if I were you.

Sovy : I’m not sure the selectors will want to know about my (26) politics, but they may want to see that I’m passionate about (27) development.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 28 to 30.

Sovy : By the way, (28-30) Vibol, in Adelaide, what did you do your Master’s in?

Vibol : Taxation Law.

Sovy : And what are you doing now?

Vibol : (28-30) I, well, I-I set up a restaurant.

Sovy : A restaurant? With a Master’s in Taxation Law?

Vibol : Taxation is a nightmare here.

To be honest, Sovy, (28-30) I just want an easy life.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 3.

Narrator : Recording 4.

Section 4. E-Waste Disposal.

You will hear a lecture on the disposal of electronic or e-waste.

Before you listen, you have 45 seconds to read questions 31 to 40.

Lecturer : Normally in this class, we design and evaluate apps, and we’ll get back to that tomorrow. This afternoon, (31) I’d like to raise your awareness about the issue of electronic waste disposal.

As some of you know, I’ve got twin daughters, who turn thirteen on Tuesday. Like many children their age, they’re totally in love with electronic devices. My husband gave his old smartphone to one of them, and I was forced to give my newish phone to the other. That was two years ago. Now, they’re both demanding brand-new smartphones of their own. As an anxious parent, I would’ve given in to this demand had I not just read an article about e-waste. Let me add that I read part of it on my tablet at home, the rest on my desktop computer at work, and, afterwards, I counted how many electronic items my family and I have at home, at school, and at work. And we’ve got 24. Yup, 24. (32) An average American family, no doubt.

Anyway, I finally agreed to birthday phones for my girls on condition that my husband and I shed some of our own devices as responsibly as we could. In the past, we’ve just put them out in the garbage as though they were banana peel or broken plates. This time, I decided to take two laptops and my girls’ phones to a recycler accredited by the Environmental Protection Agency or EPA. I found an interactive map on the EPA website showing companies that sign up to recycling schemes, called E-Stewards and Responsible Recycling Practices. It’s easy enough to drop stuff off at these companies, and receive cash in return. I do regret to say that (33) in the US the cash return is tiny because there are currently insufficient volumes of electronic trash for these companies to turn into treasure. Since I’d like to encourage this recycling practice among my students and colleagues, there’s a web link on my Facebook page.

Frankly, I don’t think Americans recycle enough. Yet, even with these companies that have popped up recently, there’s still a huge problem. I mean, the collection of the e-waste is fine, but who knows how it’s processed! (34) The EPA believes that only 20% is actually recycled, and the rest is incinerated or put in landfill. The auditing of this process has yet to begin. The majority of local e-waste, around eight million metric tons a year, is sent off abroad, mostly to Asia or Africa, where health and safety regulations scarcely exist.

One reason the US still banishes most of its e-waste is because it refused to sign the 1989 Basel Convention that controls the export of hazardous waste from rich countries to poorer ones. Needless to say, it wasn’t the only rich country to spurn the convention. Neither Canada nor Japan consented to a 1995 amendment banning such trade completely. (35) However, European signatories to the Basel Convention may not, in reality, behave any better. Inspections at ports in Germany and the Netherlands have proven that e-waste, like much other cargo, is deliberately mislabelled, so it passes unnoticed through Customs.

So, what’s inside e-waste, and who deals with most of it? Well, the list of chemicals is very long indeed. An average smartphone contains around (36) 60 different chemical elements. Heavy metals, like lead and mercury, exist alongside arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, and polyvinyl chloride – all toxic to humans in quite small amounts. When electronics are incinerated, unless at extremely high temperatures, many more toxins are produced, including halogenated dioxins and furans, which seriously contaminate the (37) food chain.

India and China are two major processors of e-waste. At present, the city of Guiyu in (38) Guangdong Province, in (38) China, is considered the world’s e-waste capital. American, Japanese, and European containers loaded with e-waste arrive in Guiyu hourly, but these days there’s also considerable waste from the rest of China, itself.

The EPA estimates that by (39) 2020, 100 million metric tons of e-waste will be produced globally each year, and, of that, only an infinitesimal amount will see its way back into more (40) electronic products.

So, designing apps for this digital age is important. As an extra assignment, I’d like those of you who are interested to create one that lets users responsibly end the lives of their many electronic devices.

Narrator : That is the end of the Listening test.

You now have ten minutes to transfer your answers to your answer sheet.

READING: Passage 1: 1. vii; 2. i; 3. viii; 4. ix; 5. iv; 6. D; 7. B; 8. C; 9. A; 10. G; 11. B; 12. A; 13. F; 14. E. Passage 2: 15. T/True; 16. T/True; 17. F/False; 18. NG/Not Given; 19. F/False; 20. NG/Not Given; 21. A; 22. D; 23. B; 24. C; 25. C; 26. D; 27. D. Passage 3: 28. B; 29. F; 30. E; 31. C; 32. A; 33. artificial // night; 34. 70; 35. 500; 36. Y/Yes; 37. N/No; 38. NG/Not Given; 39. N/No; 40. D.

The highlighted text below is evidence for the answers above.

If there is a question where ‘Not given’ is the answer, no evidence can be found, so there is no highlighted text.

A ‘When I was in school in the 1970s,’ says Tammy Chou, ‘my end-of-term report included Handwriting as a subject alongside Mathematics and Physical Education, yet, by the time my brother started, a decade later, it had been subsumed into English. I learnt two scripts: printing and cursive,* while Chris can only print.’

The 2013 Common Core, a curriculum used throughout most of the US, requires the tuition of legible writing (generally printing) only in the first two years of school; thereafter, teaching keyboard skills is a priority.

B ‘I work in recruitment,’ continues (9) Chou. ‘Sure, these days, applicants submit a digital CV and cover letter, but there’s still information interviewees need to fill out by hand, and (9) I still judge them by the neatness of their writing when they do so. Plus (1) there’s nothing more disheartening than receiving a birthday greeting or a condolence card with a scrawled message.’

C (10) Psychologists and neuroscientists may concur with Chou for different reasons. (11 and 13 are inferred; 12) They believe children learn to read faster when they start to write by hand, and they generate new ideas and retain information better. Karin James conducted an experiment at Indiana University in the US in which children who had not learnt to read were shown a letter on a card and asked to reproduce it by tracing, by drawing it on another piece of paper, or by typing it on a keyboard. Then, their brains were scanned while viewing the original image again. (2) Children who had produced the freehand letter showed increased neural activity in the left fusiform gyrus, the inferior frontal gyrus, and the posterior parietal cortex – areas activated when adults read or write, whereas all other children displayed significantly weaker activation of the same areas.

James speculates that in handwriting there is variation in the production of any letter, so the brain has to learn each personal font – each variant of ‘F’, for example, that is still ‘F’. Recognition of variation may establish the eventual representation more permanently than recognising a uniform letter printed by computer.

(7) Victoria Berninger at the University of Washington studied children in the first two grades of school to demonstrate that printing, cursive, and keyboarding are associated with separate brain patterns. Furthermore, children who wrote by hand did so much faster than the typists, who had not been taught to touch type. (7) Not only did the typists produce fewer words but also the quality of their ideas was consistently lower. (2) Scans from the older children’s brains exhibited enhanced neural activity when their handwriting was neater than average, and, importantly, the parts of their brains activated are those crucial to working memory.

(8) Pam Mueller and Daniel Oppenheimer have shown in laboratories and live classrooms that tertiary students learn better when they take notes by hand rather than inputting via keyboard. As a result, some institutions ban laptops and tablets in lectures, and prohibit smartphone photography of lecture notes. Mueller and Oppenheimer also believe handwriting aids contemplation as well as memory storage.

D Some learners of English whose native script is not the Roman alphabet have difficulty in forming several English letters: the lower case ‘b’ and ‘d’, ‘p’ and ‘q’, ‘n’ and ‘u’, ‘m’ and ‘w’ may be confused. This condition affects a tiny minority of first-language learners and sufferers of brain damage. Called dysgraphia, it appears less frequently when writers use cursive instead of printing, which is why (3) cursive has been posited as a cure for dyslexia.

E Berninger is of the opinion that (4) cursive, endangered in American schools, promotes self-control, which printing may not, and which typing – especially with the ‘delete’ function – unequivocally does not. In a world saturated with texting, where many have observed that people are losing the ability to filter their thoughts, a little more restraint would be a good thing.

A rare-book and manuscript librarian, Valerie Hotchkiss, worries about the cost to our heritage as knowledge of cursive fades. Her library contains archives from the literary giants Mark Twain, Marcel Proust, HG Wells, and others. (4) If the young generation does not learn cursive, its ability to decipher older documents may be compromised, and culture lost.

F (6) Paul Bloom, from Yale University, is (5) less convinced about the long-term benefits of handwriting. In the 1950s – indeed in Tammy Chou’s idyllic 1970s – when children spent hours practising their copperplate, what were they doing with it? Mainly copying mindlessly. For Bloom, (5, 6 & 14) education, in the complex digital age, has moved on.

It has long been known that the first one thousand days of life are the most critical in ensuring a person’s healthy future; precisely what happens during this period to any individual has been less well documented. (15) To allocate resources appropriately, public health and education policies need to be based upon quantifiable data, so the New Zealand Ministry of Social Development began a longitudinal study of these early days, with the view to extending it for two decades. Born between March 2009 and May 2010, (16) the 6,846 babies recruited came from a densely populated area of New Zealand, and (17) it is hoped they will be followed until they reach the age of 21.

Of the 6,846 babies, the majority were identified as European New Zealanders, but one quarter were Maori (indigenous New Zealanders), 20% were Pacific (originating in islands in the Pacific), and one in six were Asian. Almost 50% of the children had more than one ethnicity.

The first three reports of GUiNZ are descriptive, portraying the cohort before birth, at nine months, and at two years of age. Already, the first report, (21) Before we are born, has made history as it contains interviews with the children’s mothers and fathers. (22) The fourth report, which is more analytical, explores the definition of vulnerability for children in their first one thousand days.

Before we are born, published in 2010, describes the hopes, dreams, and realities that prospective parents have. It shows that the average age of both parents having a child was 30, and around two-thirds of parents were in legally binding relationships. However, one-third of the children were born to either a mother or a father who did not grow up in New Zealand – a significant difference from previous longitudinal studies in which a vast majority of parents were New Zealanders born and bred. Around 60% of the births in the cohort were planned, and most families hoped to have two or three children. During pregnancy, some women changed their behaviour, with regard to smoking, alcohol, and exercise, but many did not. Such information will be useful for public health campaigns.

(23) Now we are born is the second report. Fifty-two percent of its babies were male and 48% female, with nearly a quarter delivered by caesarean section. The World Health Organisation and New Zealand guidelines recommend babies be breastfed exclusively for six months, but the median age for this in the GUiNZ cohort was four months, since almost one-third of mothers had returned to full-time work. By nine months, the babies were all eating solid food. While 54% of them were living in accommodation their families owned, (23) their parents had almost all experienced a drop in income, sometimes a steep one, mostly due to mothers’ not working. Over 90% of the babies were immunised, and almost all were in very good health. Of the mothers, however, eleven percent had experienced post-natal depression – an alarming statistic, perhaps, but, once again, useful for mental health campaigns. Many of the babies were put in childcare while their mothers worked or studied, and the providers varied by ethnicity: children who were Maori or Pacific were more likely to be looked after by grandparents; European New Zealanders tended to be sent to day care.

(24) Now we are two, the third report, provides more insights into the children’s development – physically, emotionally, behaviourally, and cognitively. Major changes in home environments are documented, like the socio-economic situation, and childcare arrangements. (24) Information was collected both from direct observations of the children and from parental interviews. Once again, a high proportion of New Zealand two-year-olds were in very good health. Two thirds of the children knew their gender, and used their own name or expressed independence in some way. The most common first word was a variation on ‘Mum’, and the most common favourite first food was a banana. Bilingual or multi-lingual children were in a large minority of 40%. (25) Digital exposure was high: one in seven two-year-olds had used a laptop or a children’s computer, and 80% watched TV or DVDs daily; by contrast, 66% had books read to them each day.

(26) The fourth report evaluates twelve environmental risk factors that increase the likelihood of poor developmental outcomes for children, and draws on experiences in Western Europe, where the specific factors were collated. This, however, was the first time for their use in a New Zealand context. The factors include: (27) being born to an adolescent mother; having one or both parents on income-tested benefits; and, living in cramped conditions.

In addition to descriptive ones, future reports will focus on children who move in and out of vulnerability to see how these transitions affect their later life.

To date, GUiNZ has been highly successful with only a very small dropout rate for participants – even those living abroad, predominantly in Australia, have continued to provide information. The portrait GUiNZ paints of a country and its people is indeed revealing.

A ‘Incandescent light bulbs lit the 20th century; the 21st will be lit by LED lamps.’ So stated the Nobel Prize Committee on awarding the 2014 prize for physics to the inventors of light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

Around the world, LED systems are replacing most kinds of conventional lighting since they use about half the electricity, and the US Department of Energy expects LEDs to account for 74% of US lighting sales by 2030.

(32) However, with lower running costs, LEDs may be left on longer, or installed in places that were previously unlit. (40) Historically, when there has been an improvement in lighting technology, far more outdoor illumination has occurred. Furthermore, many LEDs are brighter than other lights, and they produce a blue-wavelength light that animals misinterpret as dawn.

According to the American Medical Association, there has been a noticeable rise in obesity, diabetes, cancer, and cardio-vascular disease in people like shift workers exposed to too much (33) artificial light of any kind. (40) It is likely more pervasive LEDs will contribute to a further rise.

B In some cities, a brown haze of industrial pollution prevents enjoyment of the night sky; in others, a yellow haze from lighting has the same effect, and it is thought that almost (34) 70% of people can no longer see the Milky Way.

When a small earthquake disabled power plants in Los Angeles a few years ago, (28) the director of the Griffith Observatory was bombarded with phone calls by locals who reported an unusual phenomenon they thought was caused by the quake – a brilliantly illuminated night sky, in which around 7,000 stars were visible. In fact, this was just an ordinary starry night, seldom seen in LA due to light pollution!

Certainly, light pollution makes professional astronomy difficult, but it also endangers humans’ age-old connection to the stars. It is conceivable that children who do not experience a true starry night may not speculate about the universe, nor may they learn about nocturnal creatures.

C (40) Excessive illumination impacts upon the nocturnal world. Around 30% of vertebrates and over 60% of invertebrates are nocturnal; many of the remainder are crepuscular – most active at dawn and dusk. (36) Night lighting, hundreds of thousands of times greater than its natural level, has drastically reduced insect, bird, bat, lizard, frog, turtle, and fish life, with even dairy cows producing less milk in brightly-lit sheds.

Night lighting has a vacuum-cleaner effect on insects, particularly moths, drawing them from as far away as 122 metres. As insects play an important role in pollination, and in providing food for birds, (36) their destruction is a grave concern. Using low-pressure sodium-vapour lamps or UV-filtered bulbs would reduce insect mortality, but an alternative light source does not help amphibians: frogs exposed to any (33) night light experience altered feeding and mating behaviour, making them easy prey.

Furthermore, birds and insects use the sun, the moon, and the stars to navigate. It is estimated that around (35) 500 million migratory birds are killed each year by collisions with brightly-lit structures, like skyscrapers or radio towers. In Toronto, Canada, the Fatal Light Awareness Program educates building owners about reducing such deaths by darkening their buildings at the peak of the migratory season. Still, over 1,500 birds may be killed within one night when this does not happen.

Non-migratory birds are also affected by light pollution – sleep is difficult, and waking up only occurs when the sun has overpowered artificial lighting, resulting in the birds’ being too late to catch insects.

(31) Leatherback turtles, which have lived on Earth for over 150 million years, are now endangered as their hatchlings are meant to follow light reflected from the moon and stars to go from their sandy nests to the sea. Instead, they follow street lamps or hotel lights, resulting in death by dehydration, predation, or accidents, since they wander onto the road in the opposite direction from the sea.

D Currently, eight percent of all energy generated in the US is dedicated to public outdoor lighting, and much evidence shows that lighting and energy use are growing at around four percent a year, exceeding population growth. In some newly industrialised countries, lighting use is rising by 20%. (37 & 40) Unfortunately, as the developing world urbanises, it also lights up brightly, rather than opting for sustainability.

E There are several organisations devoted to restoring the night sky: one is the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), based in Arizona, US. (30) The IDA draws attention to the hazards of light pollution, and works with manufacturers, planners, legislators, and citizens to encourage lighting only what is necessary when necessary.

With 58 chapters in sixteen countries, (30) the IDA has been the driving force behind the establishment of nine world reserves, most recently the 1,720-square-kilometre Rhon Biosphere Reserve in Germany. (30) IDA campaigns have also reduced street lighting in several US states, and changed national legislation in Italy.

F Except in some parks and observatory zones, the IDA does not defend complete darkness, acknowledging that urban areas operate around the clock. (39) For transport, lighting is particularly important. Nonetheless, there is an appreciable difference between harsh, glaring lights and those that illuminate the ground without streaming into the sky. The US Department of Transportation recently conducted research into highway safety, and found that a highway lit well only at interchanges was as safe as one lit along its entire length. In addition, reflective signage and strategic white paint improved safety more than adding lights.

(29) Research by the US Department of Justice showed that outdoor lighting may not deter crime. Its only real benefit is in citizens’ perceptions: lighting reduces the fear of crime, not crime itself. Indeed, bright lights may compromise safety, as they make victims and property more visible.

Some dark-sky proponents suggest that where streetlights stay on all night, they have a lower lumen rating, or are controlled with dimmers; that they point downwards, or are fitted with directional metal shields. For private dwellings, low-lumen nightlights should be activated only when motion is detected.

G It is not merely the firefly, the fruit bat, or the frog that suffers from light pollution – many human beings no longer experience falling stars or any but the brightest stars, nor consequently ponder their own place in the universe. Hopefully, prize-winning LED lights will be modified and (40) used circumspectly to return to us all the splendour of the night sky.

The chart shows tea and coffee consumption per person in 2015 in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, the United States, Turkey, and Russia.

In general, more coffee was consumed in the seven countries than tea. The UK was the only place where tea and coffee were consumed equally, at 3 kg per person.

Elsewhere, there are nationalities that had similar consumption patterns. Australians and New Zealanders were moderate tea yet high coffee consumers, with the amounts being: in Australia, 1 kg of tea to 3 of coffee; in NZ, 1.25 kg of tea to 3.75 of coffee. Likewise, Canadians and Americans consumed similar amounts of both commodities. In Canada, 0.75 kg of tea was consumed, while 6.25 kg of coffee were consumed – the highest amount of all seven countries surveyed. In the US, a negligible amount of tea was consumed – 0.5 kg, while the second-highest amount of coffee was consumed – 5.5 kg.

In 2015, Turkey and Russia bucked the trend by preferring tea to coffee. Turks consumed 5 kg of tea but 2 kg of coffee; Russians consumed 2.5 kg of tea but 1.5 kg of coffee. (189 words)

In some countries, fifteen-year-old school students are offered the choice of academic or vocational training. In this essay, I shall outline the reasons for adopting this two-stream system, and suggest its advantages.

As economies become more complex and more specialised, workers need a high degree of competence. Countries where there is an emphasis on vocational training hope to improve their economic competitiveness with a young skilled workforce. Those that have chosen to train prospective employees while still at school may have an even sharper competitive edge. In my view, an education system with a purely academic curriculum suits about 40% of students. Admittedly, people who go on to university generally find employment on graduation if not in their field, and successful post-graduates are almost invariably offered highly paid jobs. However, obtaining a degree takes time and dedication. For people who do not wish to do this, or who do not have the ability, they are far less likely to find work on leaving school where academic study has been the only option, particularly if their marks and self-esteem are low. A fortunate few do gain employment, but more commonly, even in the developed world, the majority of young school leavers are faced with unemployment – a scourge to society and a cause of distress to individuals. Therefore, countries like Germany have decided that all school students should be placed in either an academic or a vocational stream from fifteen. From an individual’s perspective, being a plumber, for example, does not only mean that drainage functions well, but that the plumber belongs to an organisation of tradespeople and is part of a respected tradition. Starting this training at the age of fifteen ensures that an adolescent has a head start with regard to jobs as well as a clear focus and sense of personal worth.

I firmly believe there needs to be an alternative curriculum to the academic at secondary; otherwise, on leaving school, too many young people are adrift, and specialised industries lack a skilled workforce. (339 words)

Narrator : Recording 5.

Test 1.

Part 1 of the Speaking test.

Listen to a candidate who is likely to be awarded a Nine answering questions in Part 1 of the Speaking test.

Examiner : Good afternoon. My name is Robert. Could you tell me your full name please?

Candidate : Carla Andrea Markulin Diaz.

Examiner : And where are you from?

Candidate : Colombia – a city called Buenaventura, on the Pacific coast.

Examiner : Could I check your ID, please?

Thanks.

First of all, Carla, I’d like to ask you a few questions about yourself.

Could you tell me what you’re doing at the moment: are you working or studying?

Candidate : I’m a student right now, but I’ve also got a part-time job.

Examiner : What do you do in your job?

Candidate : I’m a care assistant in an old people’s home. I do all kinds of things: feeding, cleaning, washing the patients, chatting to them.

Examiner : Do you like your job?

Candidate : It’s OK. I mean, it gives me enough money to live on while I’m studying, but I don’t see myself doing it after I’ve graduated.

Examiner : What do you remember about your first day in this job?

Candidate : It was pretty stressful because I had to use English all day long. Back home in Colombia, I used English at work, but mainly for emails or when foreigners came for meetings.

The other thing was that even though my name isn’t hard to say, for some reason, my boss called me Carol, then Caroline, and finally, Carlee. It was kind of funny because I’d expected the elderly residents to be forgetful, but not her.

Examiner : Now, let’s talk about taking photos.

Do you mainly take photos with your phone, or do you use a camera?

Candidate : My phone’s all right for snapshots, but my Nikon D300 has a lot more settings, and the size of the photo files is very large.

Examiner : Is there anything in particular you like to take photos of?

Candidate : Well, the Pacific coast in Colombia is beautiful, and you can see whales and dolphins at certain times of year. I’ve taken quite a few boat trips just for wildlife photography.

Examiner : Typically, what do you do with your photos after you’ve taken them?

Candidate : Honestly, I delete about 75%. Those that I do keep, I store on my laptop, and recently I’ve started leaving my laptop on with a slideshow playing when guests are at my place. I upload some of my pictures to Facebook, and a few really good ones to Flickr.

Examiner : Would you like to take classes in photography?

Candidate : Actually, I already have. I took a course at the ACP in architectural photography. I’m thinking of doing one in portraiture next.

Examiner : Let’s move on to talk about parks.

Do you go to any parks near where you live?

Candidate : I run around a little park called Bardon Park, at Coogee, almost every evening, and I sometimes go cycling in Centennial Park.

Examiner : Do you prefer a park with designated areas for leisure activities, or one that has mostly open space?

Candidate : I don’t have a preference. When I was working in Beijing last year, there were very few large parks with greenery nearby, and none that was free, but there were little ones with all kinds of equipment like you have in the gym, and I joined in with some exercises there.

In Sydney, we’re spoilt for choice. There’s any kind of park you want, including some national parks you can walk in for seven days without seeing another person.

Narrator : Recording 6.

Part 2 of the Speaking test.

Listen to Carla’s two-minute topic.

Examiner : In this part, I’m going to give you a topic for you to speak about for two minutes. Before you speak, you’ll have one minute to prepare, and you can write some notes on this paper if you like. Do you understand?

Candidate : Yes, I do.

Examiner : Here’s your topic: I’d like you to tell me about an embarrassing experience you’ve had with food.

Narrator : One minute later.

Examiner : OK?

Remember, you’re going to speak for two minutes. Don’t worry if I interrupt you to tell you when your time is up.

Could you start speaking now, please, Carla?

Candidate : Right. Well, I’ve had quite a few uncomfortable experiences with food. I mean, I’ve had some pretty bad meals in restaurants, and I went to America when I was a kid, where I was too scared to eat anything. I’m sure I was an embarrassment to my parents.

But, by far the most embarrassing food story I have is about my own cooking.

When I was sixteen, my cousin and her French fiancé came to stay with my family because he was working at the port. Well, I decided to cook some French food for them to make him feel at home, or maybe just to show off. I dunno exactly; I was only sixteen. At the time, I couldn’t really cook any Colombian food, let alone anything French! You see, in Colombia, it’s common that children have so much homework that their parents don’t let them cook, or that a maid or a cook does the cooking. Even in the holidays, every single meal was prepared for me. I guess I was spoilt.

Anyway, my cousin and her husband were staying at our place, and on the fourth or fifth night, I made a French flan with custard and fresh strawberries.

Basically what happened was that I didn’t follow the recipe. The custard needed six eggs, but we only had four, and while I could’ve asked my mother to get some more, I thought it didn’t matter if I only used four. I added some corn flour to make the custard set. When I put the flan into the oven, it was a bit wobbly, but I thought baking would help. When I took it out, it was still wobbly, and when I decorated it, the strawberries sank into the custard, so I covered the whole thing up with whipped cream, sprayed on out of an aerosol. I didn’t even know how to whip the cream.

When my mother served the dessert, my cousin said how lovely it looked, even though it was just a mountain of cream. Then, when my mother cut it – oh my God – the whole thing collapsed and dribbled all over the table. It was horrible. My cousin’s husband burst out laughing, and I spent the rest of the night in my bedroom. (378 words)

Examiner : Did you ever cook the dish again?

Candidate : No. That was the end of French cuisine for me.

Narrator : Recording 7.

Part 3 of the Speaking test.

Listen to the rest of Carla’s test.

Examiner : So you’ve told me about an embarrassing food story, and now I’d like to discuss some more general questions related to food and the food industry.

First of all: natural versus processed food.

Do people these days eat enough natural food?

Candidate : This depends on quite a few different things. It depends on where you live, what your budget is, or how much time you have, as well as on your level of education. For instance, at work, my colleagues who are nurses know what constitutes a healthy diet, but the women – especially the ones with families – just don’t have time to prepare healthy lunches for themselves. They survive on instant noodles at work, and that kind of food is about as processed as you can get.

In Colombia, the food is really wonderful, you can grow absolutely anything, but in big cities, people follow American trends, and eat a lot of junk. Obesity has risen dramatically in the past ten years.

Examiner : To what extent are food producers responsible for the health of consumers?