Firstly, tear out the Test 2 Listening / Reading Answer Sheet at the back of this book.

The Listening test lasts for about 20 minutes.

Write your answers on the pages below as you listen. After Section 4 has finished, you have ten minutes to transfer your answers to your Listening Answer Sheet. You will need to time yourself for this transfer.

After checking your answers on pp 104-108, go to page 9 for the raw-score conversion table.

PLAY RECORDING #8.

PLAY RECORDING #8.

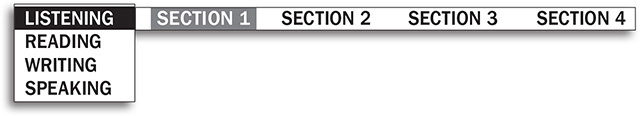

SECTION 1 Questions 1-10

RENTING AN APARTMENT

Complete the table below.

Write ONE WORD OR A NUMBER for each answer.

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

7 Peter suggests Jack’s father’s desk may not be useful because

A the space is limited.

B the apartment is furnished.

C the desk is the wrong style.

8 Peter objects to Jack’s idea about lunch because

A the neighbours may not come.

B it will be inconvenient.

C he cannot cook.

9 Jack mentions his experience with the taxi

A to tell an amusing story.

B to warn Peter about staying out late.

C to suggest neighbours can be helpful.

10 Overall, Peter and Jack think help from relatives is……useful.

A always

B sometimes

C seldom

PLAY RECORDING #9.

PLAY RECORDING #9.

SECTION 2 Questions 11-20

BEEKEEPING FOR BEGINNERS

Questions 11-15

Complete the sentences below.

Write ONE WORD OR A NUMBER for each answer.

11 Currently, the ……………….. of bees is threatened.

12 In a biologically ……………….. society, one female mates with many males.

13 Ancient Egyptians cultivated bees at least ……………….. years ago.

14 ……………….. worker honeybees live the shortest time.

15 Queen honeybees can lay up to ……………….. eggs at a time.

Answer the questions below.

Write THREE WORDS for each answer.

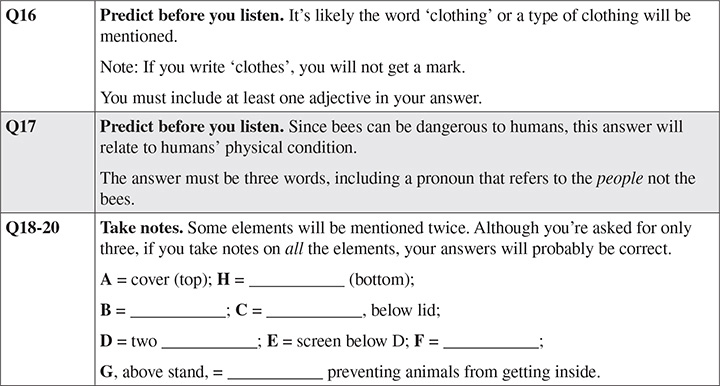

16 What should people wear when dealing directly with bees?

………………..………………..

17 What must people who would like to keep bees consider first?

………………..………………..

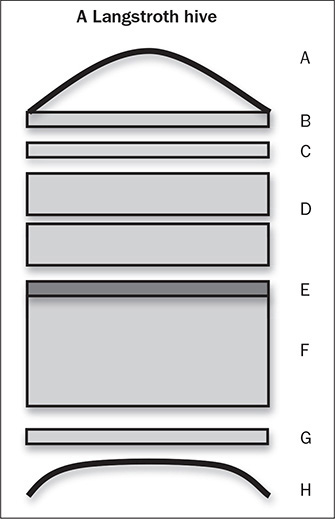

Questions 18-20

Label the diagram below.

Write the correct letter, A-H, next to questions 18-20.

18 Extractive Boxes ………………..

19 Optional Glass ………………..

20 Brood Chamber ………………..

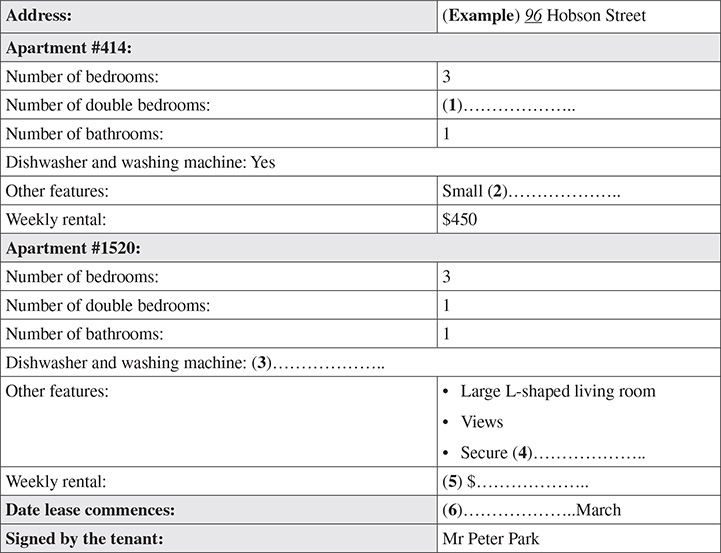

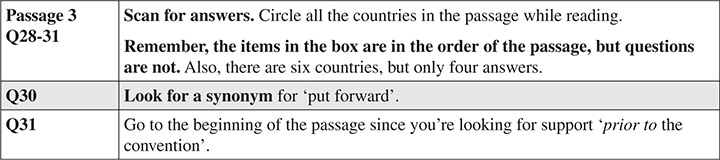

HOW TO GET A SEVEN

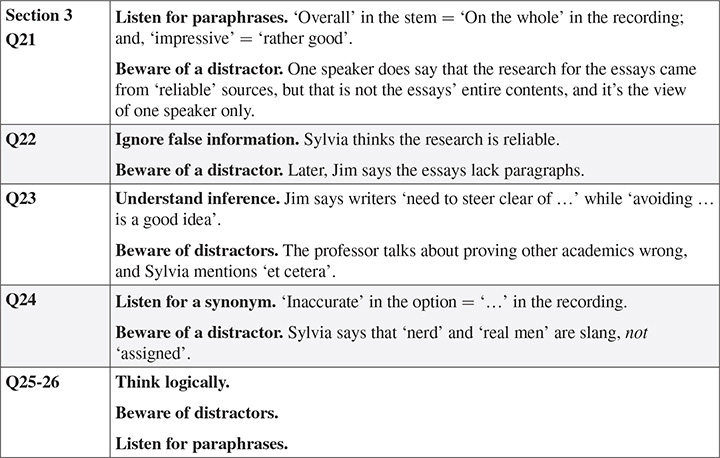

SECTION 3 Questions 21-30

RESEARCH INTO ESSAY-WRITING

Questions 21-26

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

21 Overall, Sylvia and Jim think the content of the students’ essays is

A reliable.

B impressive.

C predictable.

22 Sylvia, the female student, says that many of the essays she read

A had insufficient research.

B seemed like oral presentations.

C lacked paragraphing.

23 Jim, the male student, says that good academic writers

A avoid words like ‘should’ and ‘never’.

B often prove other academic writers wrong.

C use expressions like ‘et cetera’.

24 According to the professor, in: ‘Men who avoid cigarettes may be assigned as nerds’, the word ‘assigned’ is

A ambiguous.

B slang.

C inaccurate.

25 What is the problem with the word ‘smocking’ in the students’ essays?

A It is wrongly spelt.

B It is rather old-fashioned.

C A spell checker won’t find it.

26 What is ‘smocking’?

A Decoration on clothing

B A kind of honeycomb

C A serious illness

In the professor’s opinion, what do good academic writers do?

Choose THREE answers from the box, and write the correct letter, A-H, next to questions 27-29.

They:

A write a single draft.

B write fewer words than poor writers.

C use unusual vocabulary.

D punctuate carefully.

E avoid personal pronouns.

F avoid giving opinions.

G do a lot of research.

H give their readers pleasure.

Question 30

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

30 The professor asks Sylvia to

A limit her theoretical research.

B collect some more student essays.

C meet again in one month’s time.

PLAY RECORDING #11.

PLAY RECORDING #11.

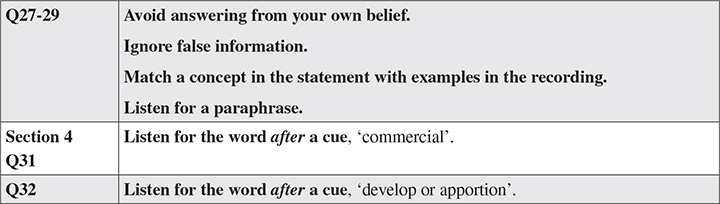

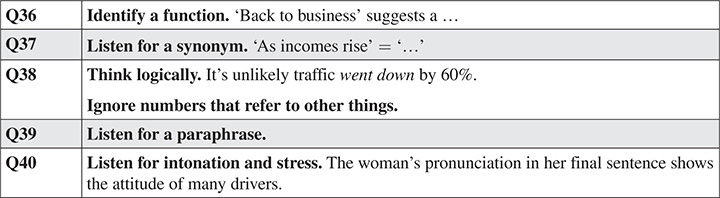

SECTION 4 Questions 31-40

ROAD CONGESTION AND MARKET FAILURE

Questions 31-35

Complete the sentences below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS for each answer.

31 Road congestion, carbon emissions, and commercial ……………….. are examples of market failure.

32 The lecturer defines market failure as the inability of the free market to develop or apportion ……………….. efficiently.

33 Some markets fail completely because firms cannot seek profit within those markets. The lecturer gives the example of ………………...

34 Markets fail partially in many ways, one of which is ……………….. – when too many goods or services are produced.

35 Negative externalities are the failure of consumers or producers consider the results of their actions on third ………………...

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

36 The speaker’s story about London traffic in 1916 is

A an entertaining apology.

B a relevant digression.

C an amusing story.

37 What connection does the lecturer make between public transport and wealth?

A As public transport becomes more convenient, more people use it.

B Use of public transport declines as wealth increases.

C Like alcohol and vacations, there are fashions in public transport use.

38 Road traffic was reduced in central London from 2011 to 2014 by more than

A 10%.

B 30%.

C 60%.

39 How does the lecturer evaluate new road building and congestion charging?

A They are equally ineffective.

B Road construction is less effective than congestion charging.

C Congestion charging is less effective than road construction.

40 The lecturer thinks most drivers who contribute to congestion are

A unaware.

B undecided.

C unconcerned.

Firstly, turn over the Test 2 Listening Answer Sheet you used earlier to write your Reading answers on the back.

The Reading test lasts exactly 60 minutes.

Certainly, make any marks on the pages below, but transfer your answers to the answer sheet as you read since there is no extra time at the end to do so.

After checking your answers on pp 111-113, go to page 9 for the raw-score conversion table.

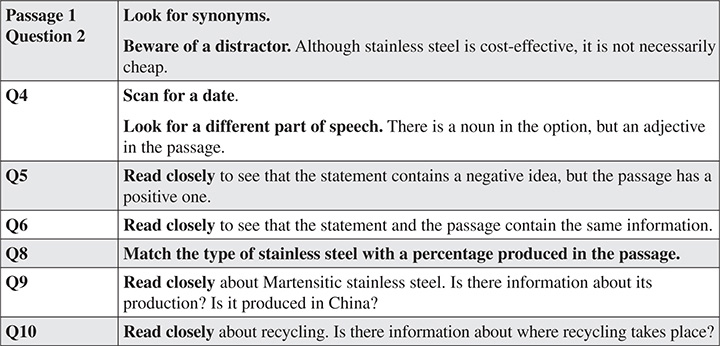

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-14, based on Passage 1 below.

Uses

In any ordinary kitchen, there are numerous items made from stainless steel, including cutlery, utensils, and appliances. ‘Inox’ or ‘18/10’ may be stamped on the base of a good stainless steel pot: ‘Inox’ is short for the French inoxydable; while 18 refers to the percentage of chromium in the stainless steel, and 10 to its nickel content.

In hospitals, laboratories and factories, stainless steel is used for many instruments and pieces of equipment because it can easily be sterilised, and it remains relatively bacteria-free, thus improving hygiene. Since it is mostly rust-free, stainless steel also does not need painting, so proves cost-effective.

As a decorative element, stainless steel has been incorporated into skyscrapers, like the Chrysler Building in New York, and the Jin Mao Building in Shanghai, the latter considered one of the most stunning contemporary structures in China. Bridges, monuments, and sculptures are often stainless steel; and, cars, trains, and aircraft contain stainless steel parts.

Recent alloys

As most pure metals serve little practical purpose, they are often combined or alloyed. Some examples of ancient alloys are bronze (copper + tin) and brass (copper + zinc). Carbon steel (iron + carbon), first made in small quantities in China in the sixth century AD, was produced industrially only in mid-nineteenth-century Europe. Stainless steel, which retains the strength of carbon steel with some added benefits, consists of iron, carbon, chromium, and nickel, and may contain trace elements. Stainless steel is a new invention – Austenitic stainless steel was patented by German engineers in 1912, the same year that Americans created ferritic stainless steel, while Martensitic stainless steel was patented as late as 1919.

Properties

The name, stainless steel, is misleading since, where there is very little oxygen or a great amount of salt, the alloy will, indeed, stain. In addition, stainless steel parts should not be joined together with stainless steel nuts or bolts as friction damages the elements; another alloy, like bronze, or pure aluminium or titanium must be used.

In general, stainless steel does not deteriorate as ordinary carbon steel does, which rusts in air and water. Rust is a layer of iron oxide that forms when oxygen reacts with the iron in carbon steel. Because iron oxide molecules are larger than those of iron alone, they wear down the steel, causing it to flake and eventually snap. Stainless steel, however, contains between 13-26% chromium, and, with exposure to oxygen, forms chromium oxide, which has molecules the same size as the iron ones beneath, meaning they bond strongly to form an invisible film that prevents oxygen or water from penetrating. As a result, the surface of stainless steel neither rusts nor corrodes. Furthermore, if scratched, the protective chromium-oxide layer of stainless steel repairs itself in a process known as passivation, which also occurs with aluminium, titanium, and zinc.

There are over 150 grades of stainless steel with various properties, each distinguished by its crystalline structure. Austenitic stainless steel, comprising 70% of global production, is barely magnetic, but ferritic and Martensitic stainless steel function as magnets because they contain more nickel or manganese. Ferritic stainless steel – soft and slightly corrosive – is cheap to produce, and has many applications, while Martensitic stainless steel, with more carbon than the other types, is incredibly strong, so it is used in fighter jet bodies, but is also the costliest to produce.

Recyclability

Stainless steel can be recycled completely, and these days, the average stainless steel object comprises around 60% of recycled material.

Cutting-edge application

In the last few years, 3D printers have become widespread, and stainless steel infused with bronze is the hardest material that a 3D printer can currently use.

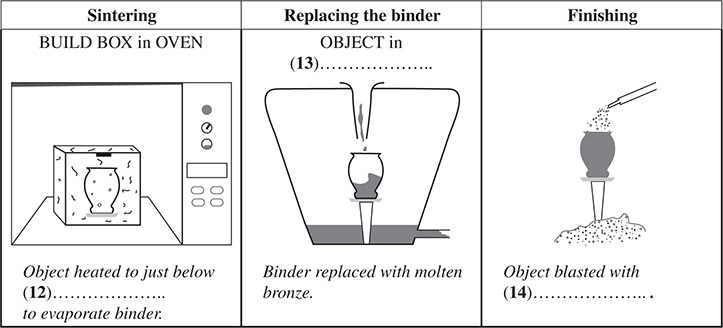

In 3D printing, an inkjet head deposits alternate layers of stainless steel powder and organic binder into a build box. After each layer of binder is spread, overhead heaters dry the object before another layer of powder is added. Upon completion of printing, the whole object, still in its build box, is sintered in an oven, which means the object is heated to just below melting point, so the binder evaporates. Next, the porous object is placed in a furnace so that molten bronze can replace the binder. To finish, the object is blasted with tiny beads that smooth the surface.

Appraisal

In less than a century, stainless steel has become essential due to its relatively cheap production cost, its durability, and its renewability. Used in the new manufacturing process of 3D printing, its future looks bright.

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 1-4 on your answer sheet.

1 A stainless steel pot with ‘18/10’ stamped on it contains

A 18% carbon and 10% iron.

B 18% iron and 10% carbon.

C 18% chromium and 10% nickel.

D 18% nickel and 10% chromium.

2 Hospitals and laboratories use stainless steel equipment because it

A is easy to clean.

B is inexpensive.

C is not disturbed by magnets.

D withstands high temperatures.

3 Stainless steel has been used in some famous buildings for its

A durability.

B beauty.

C modernity.

D reflective quality.

4 The first type of stainless steel was patented in

A China in 1912.

B Germany in 1912.

C the UK in 1919.

D the US in 1919.

Questions 5-11

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 1?

In boxes 5-11 on your answer sheet, write:

5 Stainless steel does not stain.

6 Carbon steel rusts as its surface molecules are smaller than those of iron oxide.

7 Passivation is unique to stainless steel.

8 Austenitic stainless steel is the most commonly produced type.

9 These days, Martensitic stainless steel is mainly produced in China.

10 Currently, the recycling of stainless steel takes place in many countries.

11 Close to two-thirds of a stainless steel object is made up of recycled metal.

HOW TO GET A SEVEN

Label the diagrams below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 12-14 on your answer sheet.

3D printing using stainless steel and bronze

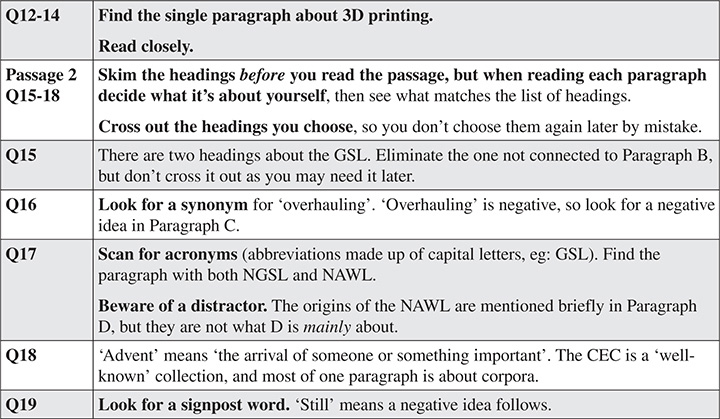

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 15-27, based on Passage 2 below.

Questions 15-19

Passage 2 has six paragraphs: A-F.

Choose the correct heading for paragraphs B-F from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number, i-ix, in boxes 15-19 on your answer sheet.

15 Paragraph B

16 Paragraph C

17 Paragraph D

18 Paragraph E

19 Paragraph F

Word lists

A As any language learner knows, the acquisition of vocabulary is of critical importance. Grammar is useful, yet communication occurs without it. Consider the utterance: ‘Me station.’ Certainly, ‘I’d like to go to the station’ is preferable, but a taxi driver will probably head to the right place with ‘Me station.’ If the passenger uses the word ‘airport’ instead of ‘station’, however, the journey may well be fraught. Similarly, ‘What time train Glasgow?’ signals to a station clerk that a timetable is needed even though ‘What time does the train go to Glasgow?’ is correct. In both of these requests, nouns – ‘station’, ‘time’, ‘train’, and ‘Glasgow’ – carry most of the meaning; and, generally speaking, foreign-language learners, like infants in their mother tongue, acquire nouns first. Verbs also contain unequivocal meaning; for instance, ‘go’ indicates departure not arrival. Furthermore, ‘Go’ is a common word, appearing in both requests above, while ‘the’ and ‘to’ are the other frequent items. Thus, for a language learner, there may be two necessities: to acquire both useful and frequent words, including some that function grammatically. It is a daunting fact that English contains around half a million words, of which a graduate knows 25,000. So how does a language learner decide which ones to learn?

B The General Service List (GSL), devised by the American, Michael West, in 1953, was one renowned lexical aid. Consisting of 2,000 headwords, each representing a word family, GSL words were listed alphabetically, with definitions and example sentences, while a number alongside each word showed its number of occurrences per five million words, and a percentage beside each meaning indicated how often that meaning occurred. For 50 years, particularly in the US, the GSL wielded great influence: graded readers and other materials for primary schools were written with reference to it, and American teachers of English as a foreign language (EFL) relying heavily upon it.

C Understandably, West’s 1953 GSL has been updated several times because, firstly, his list contained archaisms such as ‘shilling’, while lacking words that existed in 1953 but which were popularised later, like ‘drug’, ‘OK’, ‘television’, and ‘victim’. Naturally, his list did not contain neologisms such as ‘email’. However, around 80% of West’s original inclusions were still considered valid, according to researchers Billuro lu and Neufeld (2005). Secondly, what constituted a headword and a word family in the West’s GSL was not entirely logical, and rules for this were formulated by Bauer and Nation (1995). Thirdly, technological advance has meant that billions of words can now be analysed by computer for frequency, context, and regional variation. West’s frequency data was based on a 2.5-million-word corpus drawn from research by Thorndike and Lorge (1944), and some of it was unreliable. A 2013 incarnation of the GSL, called the New General Service List (NGSL), used a 273-million-word subsection of the Cambridge English Corpus (CEC), and research indicates this list provides a higher degree of coverage than West’s.

lu and Neufeld (2005). Secondly, what constituted a headword and a word family in the West’s GSL was not entirely logical, and rules for this were formulated by Bauer and Nation (1995). Thirdly, technological advance has meant that billions of words can now be analysed by computer for frequency, context, and regional variation. West’s frequency data was based on a 2.5-million-word corpus drawn from research by Thorndike and Lorge (1944), and some of it was unreliable. A 2013 incarnation of the GSL, called the New General Service List (NGSL), used a 273-million-word subsection of the Cambridge English Corpus (CEC), and research indicates this list provides a higher degree of coverage than West’s.

D A partner to the NGSL is the 2013 New Academic Word List (NAWL) with 2,818 headwords – a modification of Averill Coxhead’s 2000 AWL. The NAWL excludes NGSL words, focusing on academic language, but, nevertheless, items in it are generally serviceable – they are merely not used often enough to appear in the NGSL. An indication of the difference between the two lists can be seen in just four words: the NGSL begins with ‘a’ and ends with ‘zonings’, whereas ‘abdominal’ and ‘yeasts’ open and close the NAWL.

E Over time, linguistics and EFL have become more dependent upon computerized statistical analysis, and large bodies of words have been collected to aid academics, teachers, and learners. One such body, known by the Latin word for body, ‘corpus’, is the CEC, created at Cambridge University in the UK. This well-known collection has two billion words of written and spoken, formal and informal, British, American, and other Englishes. Continually updated, its sources are very wide indeed – far wider than West’s. Although the CEC is one of many English-language corpora, it is not the largest, but it was the one used by the creators of the NGSL and the NAWL.

F Still, a learner cannot easily access corpora, and even though the NGSL and NAWL are free online, a learner may not know how best to use them. Linguists have demonstrated that words should be learnt in a context (not singly, not alphabetically); that items in the same lexical set should be learnt together; that it takes at least six different sightings or hearings to learn one item; that written language differs significantly from spoken; and, that concrete language is easier to acquire than abstract. Admittedly, a list of a few thousand words is not so hard to learn, but language learning is not only about frequency and utility, but also about passion and poetry. Who cares if a word you like isn’t in the top 5,000? If you like it or the way it sounds, you’re likely to learn it. And, if you use it correctly, at least your IELTS examiner will be impressed.

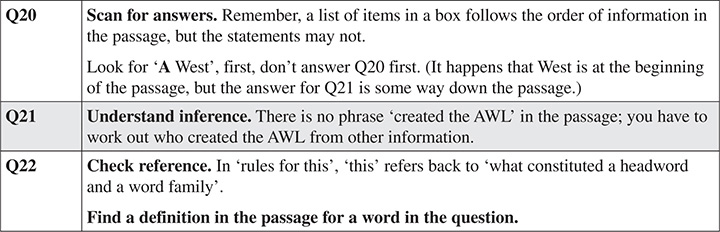

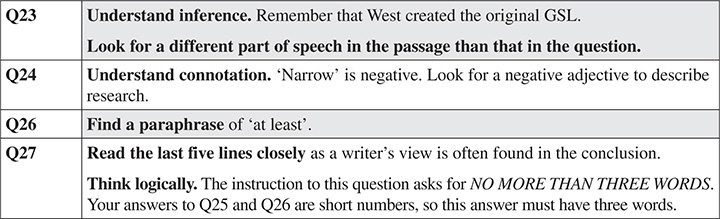

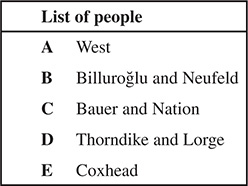

Questions 20-24

Look at the following statements and the list of people on the following page.

Match each statement with the correct person or people: A-E.

Write the correct letter, A-E, in boxes 20-24 on your answer sheet.

20 He / She / They created the GSL.

21 He / She / They created the AWL.

22 He / She / They standardised headwords and word families.

23 He / She / They reviewed the GSL for content validity.

24 His / Her / Their early research was narrow.

Questions 25-27

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND / OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 25-27 on your answer sheet.

25 How many words are there in the complete Cambridge English Corpus?

…………………….

26 At least how many times must a learner see or hear a new word before it can be learnt?

…………………….

27 According to the writer, what else must there be a sense of for a person to learn a new word?

…………………….

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 28-40, based on Passage 3 below.

Almost all cultures raise monuments to their own achievements or beliefs, and preserve artefacts and built environments from the past.

There has been considerable interest in saving cultural sites valuable to all humanity since the 1950s. In particular, an international campaign to relocate pharaonic treasures from an area in Egypt where the Aswan Dam would be built was highly successful, with more than half the project costs borne by 50 different countries. Later, similar projects were undertaken to save the ruins of Mohenjoh-daro in Pakistan and the Borobodur Temple complex in Indonesia.

The idea of listing world heritage sites (WHS) that are cultural or natural was proposed jointly by an American politician, Joseph Fisher, and a director of an environmental agency, Russell Train, at a White House conference in 1965. These men suggested a programme of cataloguing, naming, and conserving outstanding sites, under what became the World Heritage Convention, adopted by UNESCO* in November 1972, and effective from December 1975. Today, 191 states and territories have ratified the convention, making it one of the most inclusive international agreements of all time. The UNESCO World Heritage Committee, composed of representatives from 21 UNESCO member states and international experts, administers the programme, albeit with a limited budget and few real powers, unlike other international bodies, like the World Trade Organisation or the UN Security Council.

In 2014, there were 1,007 WHS around the world: 779 of them, cultural; 197 natural; and, 31 mixed properties. Italy, China, and Spain are the top three countries by number of sites, followed by Germany, Mexico, and India.

Legally, each site is part of the territory of the state in which it is located, and maintained by that entity, but as UNESCO hopes sites will be preserved in countries both rich and poor, it provides some financial assistance through the World Heritage Fund. Theoretically, WHS are protected by the Geneva Convention, which prohibits acts of hostility towards historic monuments, works of art, or places of worship.

Certainly, WHS have encouraged appreciation and tolerance globally, as well as proving a boon for local identity and the tourist industry. Moreover, diversity of plant and animal life has generally been maintained, and degradations associated with mining and logging minimised.

Despite good intentions, significant threats to WHS exist, especially in the form of conflict. The Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo is one example, where militias kill white rhinoceros, selling their horns to purchase weapons; and, in 2014, Palmyra – a Roman site in northern Syria – was badly damaged by a road built through it, as well as by shelling and looting. In fact, theft is a common problem at WHS in under-resourced areas, while pollution, nearby construction, or natural disasters present further dangers.

But most destructive of all is mass tourism. The huge ancient city of Angkor Wat, in Cambodia, now has over one million visitors a year, and the nearby town of Siem Reap – a village 20 years ago – now boasts an international airport and 300 hotels. Machu Picchu in Peru has been inundated by tourists to the point where it may now be endangered. Commerce has altered some sites irrevocably. Walkers along the Great Wall near Beijing are hassled by vendors flogging every kind of item, many unrelated to the wall itself, and extensive renovation has given the ancient wonder a Disneyland feel.

In order for a place to be listed as a WHS, it must undergo a rigorous application process. Firstly, a state takes an inventory of its significant sites, which is called a Tentative List, from which sites are put into a Nomination File. Two independent international bodies, the International Council on Monuments and Sites, and the World Conservation Union, evaluate the Nomination File, and make recommendations to the World Heritage Committee. Meeting once a year, this committee determines which sites should be added to the World Heritage List by deciding that a site meets at least one criterion out of ten, of which six are cultural, and four are natural.

In 2003, a second convention, effective from 2008, was added to the first. The Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage has so far been ratified by 139 states – a notable exception being the US. Aiming to protect traditions rather than places, 267 elements have already been enshrined, including: Cambodia’s Royal Ballet; the French gastronomic meal; and, watertight-bulkhead technology of Chinese junks.

The World Heritage Committee hopes that the states that agree to list such elements will also promote and support them, although, once again, commercialisation is problematic. For instance, after the French gastronomic meal was listed in 2010, numerous French celebrity chefs used the designation in advertising, and UNESCO debated delisting the element. The US has chosen not to sign the second convention due to implications to intellectual property rights. As things stand, with the first treaty, the US has far fewer nominated sites than its neighbour Mexico, partly because some Mexican sites are entire towns or city centres, and the US has no desire for its urban planning to be restricted by world-heritage status. St Petersburg, in Russia, which has its entire historic centre as a WHS, introduced strict planning regulations to maintain its elegant 18th-century appearance, only to discover thousands of minor infringements by owners preferring to do what they pleased with their properties.

With intangible elements, changes over time, due to modernisation or globalization, may be greater than those threatening buildings. Opponents of the second convention believe traditions should not be frozen in time, and are equally unconcerned if traditions dwindle or die.

Although the 1972 World Heritage Convention lacks teeth, and many of its sites are suffering, and although the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage has proven less popular, it would seem that the overall performance of these two instruments has been very good.

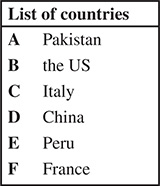

Questions 28-31

Look at the following statements and the list of countries below.

Match each statement with the correct country, A-F, below.

Write the correct letter, A-F, in boxes 28-31 on your answer sheet.

28 It has the most world heritage sites.

29 Mass tourism has seriously threatened one of its sites.

30 Two men from here put forward the idea of a convention.

31 There was international support for a project here prior to the convention.

Complete the flowchart below.

Choose ONE WORD OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 32-35 on your answer sheet.

Questions 36-40

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-G, below.

Write the correct letter, A-G, in boxes 36-40 on your answer sheet.

36 The Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage is designed to

37 The World Heritage Committee worries about

38 The US refused to sign the 2003 convention due to concerns about

39 Russian property owners have been annoyed by what they see as

40 Critics of the 2003 convention are not disturbed by

A changes to or disappearance of traditions.

B price rises due to world-heritage listing.

C over-regulation connected to world-heritage listing.

D protect traditions.

E protect built environments.

F intellectual property rights.

G the commercial exploitation of listed traditions.

The Writing test lasts for 60 minutes. It has two tasks. Task 2 is worth twice as much as Task 1. Although candidates are assessed on four criteria for each task, an overall band, from 1-9, is awarded.

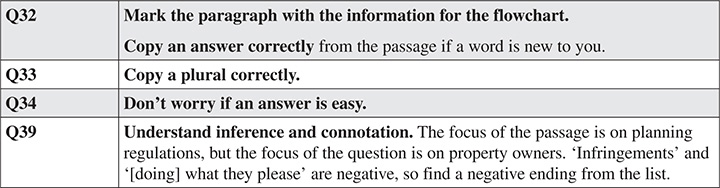

Task 1

Spend about 20 minutes on this task.

The two plans below show Pancha Village in 2005 and 2015.

Write a summary of the information. Select and report the main features, and make comparisons where necessary.

Write at least 150 words.

Task 2

Spend about 40 minutes on this task.

Write about the following topic:

Many developed countries now have large numbers of people over the age of 65.

What problems might this cause?

How can the problems be solved?

Provide reasons for your answer, including relevant examples from your own knowledge or experience.

Write at least 250 words.

PART 1

How might you answer the following questions?

1 Tell me about the accommodation you’re currently living in.

2 Do you have a favourite part of the house?

3 Do you think you’ll stay where you’re living for a while?

4 Let’s move on to talk about hats and caps. Do you ever wear a hat or a cap?

5 Why do some people wear hats or caps?

6 Do you think headgear was more popular in the past? Why?

7 Now, let’s talk about time. When was the last time you were rather late?

8 How do you feel when other people are late?

9 Do you think people these days have enough time?

10 How do you think children perceive time?

PLAY RECORDING #12 TO HEAR PART ONE OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

PLAY RECORDING #12 TO HEAR PART ONE OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

PART 2

How might you speak about the following topic for two minutes?

I’d like you to tell me about someone you think is attractive.

* Who is this person?

* Why is he or she attractive?

* How does this person dress?

And, what do other people think about this person’s looks?

PLAY RECORDING #13 TO HEAR PART TWO OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

PLAY RECORDING #13 TO HEAR PART TWO OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

PART 3

How might you answer the following questions?

1 First of all, physical appearance and societal pressure.

Do you think these days, there’s an over-emphasis on conforming to a norm, or on looking beautiful?

What are some of the dangers of this pressure to be attractive?

2 Let’s talk about concepts of beauty throughout time.

Do you think our idea of beauty has changed over time, or basically stayed the same?

PLAY RECORDING #14 TO HEAR PART THREE OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

PLAY RECORDING #14 TO HEAR PART THREE OF THE SPEAKING TEST.

Go to pp 112-114 for the recording scripts.

LISTENING:

Section 1: 1. 2/two; 2. balconies; 3. Yes; 4. garage // parking; 5. 610; 6. 9/9th/the ninth (of); 7. A; 8. B; 9. C; 10. B. Section 2: 11. survival; 12. eusocial; 13. 4,500; 14. female; 15. 2,000; 16. Good protective clothing; 17. Their allergic reaction (must include ‘their’); 18. D; 19. C; 20. F. Section 3: 21. B; 22. B; 23. A; 24. C; 25. C; 26. A; 27-29. BEH (in any order); 30. A. Section 4: 31. fishing; 32. resources; 33. street lighting; 34. over-supply/over supply; 35. parties; 36. B; 37. B; 38. A; 39. A; 40. C.

The highlighted text below is evidence for the answers above.

Narrator : Recording 8.

Practice Listening Test 2.

Section 1. Renting an Apartment.

You will hear two men talking about renting an apartment with a third man.

Read the example.

Peter : Hi Jack. Sorry I’m late.

Jack : No problem, Peter. We’re still waiting for Mike.

So, what did you think about 96 Hobson Street?

Peter : It’s great.

Narrator : The answer is ‘96’.

On this occasion only, the first part of the conversation is played twice.

Before you listen again, you have 30 seconds to read questions 1 to 6.

Peter : Hi Jack. Sorry I’m late.

Jack : No problem, Peter. We’re still waiting for Mike.

So, what did you think about 96 Hobson Street?

Peter : It’s great.

Jack : You don’t think the building’s too noisy, so close to the motorway?

Peter : It depends which apartment we take.

Jack : What are our options?

Peter : At the moment, there are two apartments available: one on the fourth floor; the other, higher up.

Jack : Do they get views?

Peter : Apartment 1520 does.

Jack : Last night, I went online and took a virtual tour of the building. One thing I noticed was that three-bedroom apartments have only one double bedroom.

Peter : Mostly, that’s true, but apartment 414 has (1) two.

Jack : What about bathrooms?

Peter : A single bathroom in each apartment.

Jack : And (2) balconies?

Peter : Four fourteen has two small (2) balconies off the bedrooms.

Jack : The kitchens in the tour looked good, but I can’t remember whether they come with a dishwasher and a washing machine.

Peter : (3) Yes, they do.

The kitchen in 1520 is quite small, but there’s a large L-shaped living room to compensate.

Jack : I know Mike’s got a car. Is there a (4) garage?

Peter : Secure (4) parking is limited to tenants who pay over $600 a week.

Jack : How much is the rental on the apartments you saw?

Peter : Four Fourteen is $450, and 1520 is (5) $610.

Jack : That’s quite a difference.

Peter : Yeah.

Jack : And 1520’s only got one double bedroom, right?

Peter : Uh huh. But it’s facing away from Hobson Street, so it’ll be quiet, and Mike’s car would be safe.

Peter : I’m planning to sign the lease on Friday.

The agent wants it to start in the second or third week of March.

Jack : I’ll be away until the seventh.

Peter : All right. Let’s have it start on the (6) ninth.

Jack : The (6) ninth sounds fine.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 7 to 10.

Jack : Looks like Mike won’t be here for another 20 minutes.

Peter : That’s a pity.

I wonder if we could use his car to move?

Jack : I’m sure we’ll be able to.

(10 useful & useless) My dad said he’d lend a hand too, and he’s got a truck.

Peter : That’d be good. With a truck we could move everything in one go.

Jack : (10) He’s also got lots of stuff he doesn’t need anymore – plates bowls, pots and pans, and a big old wooden desk.

Peter : (7) I doubt that a large desk would fit in any of the bedrooms. What we really need is a couch and some things to decorate the living room.

Jack : When I rented last year, we spent lots of time before we moved in choosing nice furniture and decorations, but we neglected the basics, like rubbish bins and cleaning supplies. (10 useless) Then, there was the problem that some people gave us weird things, like a device my aunt bought for chopping onions. I mean, all you need is a sharp knife, right?

Peter : Yeah.

Jack : But we did do one great thing, which we should try again: we invited the neighbours to lunch one Saturday.

Peter : Complete strangers? (8) What about the cost?

Jack : The meal doesn’t have to be fancy, and not everyone we ask will come.

Peter : Why bother? Especially when (8) I’ll miss the football.

Jack : It’s just a way to show that, even though we’re students, we’re generous and approachable.

Peter : OK.

Jack : And it does pay off. One night I came home in a taxi very late. Suddenly, I realised (9) I couldn’t pay the driver because I’d left my wallet somewhere, so I ran upstairs, knocked on my neighbour’s door, and he lent me some money.

Peter : Lucky you.

All right. To sum up: we’re borrowing your dad’s truck; (10 useful) we’re accepting some useful things from relatives; and, we’re getting to know our neighbours.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 1.

Narrator : Recording 9.

Section 2. Beekeeping for beginners.

You will hear a man talking about beekeeping for beginners.

Before you listen, you have 30 seconds to read questions 11 to 15.

Beekeeper : Good morning.

As you may be aware, all over the world, bees are under threat. For their (11) survival, the goodwill and hard work of enthusiasts like you is vital.

Today, I’ll present some facts about bees and beekeeping. Then, I’ll show you a Langstroth hive, which is a type commonly used by beekeepers.

Bees and bee products can be eaten, and beeswax used to make candles and cosmetics. And of course, bees pollinate plants, so are essential in agriculture.

There are many kinds of bees: solitary and social. Social bees live in colonies in the wild, and can be cultivated in hives.

The word (12) eusocial describes the organisation of bee society. It’s spelt (12) EU plus social. It means there’s one single reproductively active female to several males. It also signals a division of labour, and co-operative care of the young by non-breeding individuals. In addition to honeybees, there are (12) eusocial ants, termites, and naked vole rats.

Before humans cultivated honeybees, wild colonies were raided, and sadly, this continues today. In Spain, 8,000-year-old rock drawings depict such raids while Egyptian tomb paintings from (13) 4,500 years ago show domesticated bees. However, the ancient Egyptians did not understand bee society, and killed most of their insects in the quest for honey. Hives with moveable parts that ensure continual honey collection and the safety of the queen were designed just 170 years ago by the American, Lorenzo Langstroth.

It is only in the last 300 years that the functions of the different parts of a bee colony and of the three types of honeybees, themselves, have been understood.

A queen honeybee is the largest and most important member of honeybee society. She lives far longer than the other bees, up to three years; and, her pheromones control the colony. Drones, or male honeybees, make up around ten percent of a colony, and live for just four months. They mate with queens and forage, but do little else. (14) Female worker honeybees, constituting 90% of a colony, have a mere six-week lifespan, yet they are the busiest creatures: guarding, cleaning, nursing, fanning, and foraging.

The queen lays eggs after she has been inseminated by a drone while flying in the open air. She can lay up to (15) 2,000 eggs at one time. When unmated queens hatch from those 2,000 eggs, they will fight to the death, or one will fly away with a swarm to form her own colony elsewhere. The beauty of a Langstroth hive is that a beekeeper can separate out the laying queen, and easily kill egg cells containing potential queens.

Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 16 to 20.

So let’s look at some slides of a Langstroth hive. I can’t open my own outside as it’s winter, and not much is happening, but also because we’d all need to be wearing (16) good protective clothing. Bees sting, remember, and their venom is poisonous. Two percent of people who are stung experience an uncomfortable allergic reaction, and, without medical intervention, a tiny minority die from toxic shock. Anyone who’d like to keep bees must first determine (17) their allergic reaction first.

OK. Here’s a Langstroth hive with nine elements. It stands at 1.5 metres, and contains (18) extractive boxes, from where you take the honey, and (20) a brood chamber, where the queen breeds. This hive’s got two extractive boxes, but you can build it up to five.

The hive is wooden, with a cover and a stand at top and bottom. There’s always a wooden lid, letter B on your diagram, and, (19) if keepers collect venom, there’s a sheet of glass below the lid. (18) The extractive boxes are shallow because they’re frequently handled. They hold 30 kilos of honey each, and a beekeeper couldn’t lift one if it were any deeper. The thin screen beneath (18) the lower extractive box has holes that drones and worker bees can crawl through, but which are too small for the queen. She, therefore, remains in (20) the deep brood chamber, where the eggs are laid. The final element, above the stand, is a board that prevents other animals from getting inside.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 2.

Narrator : Recording 10.

Section 3. Research into essay-writing.

You will hear two post-graduate students talking to their professor about their research into academic essay-writing.

Before you listen, you have 30 seconds to read questions 21 to 26.

Professor : Come in, Sylvia. Come in Jim.

How are you?

Sylvia : A bit tired, actually. I read 75 of the essays about smoking over the weekend.

Professor : And you, Jim?

Jim : I’m fine. I’ve read 20 so far. They’re pretty interesting – a really good sample for our research.

Sylvia : Yes, I found them stimulating.

(21) On the whole, their content is rather good. The students have done a fair bit of research.

Jim : That’s true.

Sylvia : And they quote from reliable sources.

The problems are more with style. (22) Many of the ones I read seemed like oral presentations instead of academic essays.

Jim : I’d agree with that.

Sylvia : For a start, some of the vocabulary was inappropriate. Take this sentence from a conclusion: ‘To get smokers to cut down or give up, there should be more ads on TV about the health problems et cetera.’

Professor : Yes. Students forget that ‘get’ and most phrasal verbs are spoken.

Jim : Also, (23) they need to steer clear of ‘should’ and ‘must’. When a writer has a hypothesis to prove, he or she doesn’t want to put the readers off with such strong language.

A writer needs to use verbs like ‘could’ or ‘might’ instead. (23) And avoiding adverbs like ‘always’ and ‘never’ is a must. After all, you never know when you’ll be proven wrong!

Professor : Absolutely. Over the years, many colleagues have challenged my academic papers.

I see you’ve circled ‘et cetera’, Sylvia, on several essays.

Sylvia : ‘Et cetera’ is OK in note taking but not in academic writing.

Jim : Here’s something else related to vocabulary. It’s part of an argument about why people start smoking. At least, I think the student’s written ‘smoking’. Maybe it’s ‘smocking’?

Sylvia : Go on.

Jim : ‘Men who avoid cigarettes may be assigned as nerds. This ideology makes them dare to join in smocking activities to let us know they’re real men.’

Professor : That is interesting. I mean, there’s an attempt at sophistication, (24) with ‘assigned’ and ‘ideology’, but they’re both used incorrectly.

Jim : And ‘nerd’ and ‘real men’ are slang.

Sylvia : Going back to the word ‘smocking’. I read five essays out of 75 in which students wrote about ‘smocking’. I must say it made me chuckle!

Professor : (25) What it does reveal is the danger of spell checkers – they can’t alert a writer to words that really do exist.

Jim : What exactly is ‘smocking’?

Sylvia : Here’s a dictionary definition: (26) ‘Ornamentation on a garment made by gathering together a section of material into tight pleats and sewing across it to make a pattern similar to a honeycomb.’

Jim : It sounds old-fashioned to me.

Sylvia : Yes, I had it on a dress when I was a girl.

Jim : Whatever was it doing in an essay on smoking?

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 27 to 30.

Professor : So, let’s discuss what good academic writers do. How do they avoid the embarrassment of writing about ‘smocking’?

Sylvia : Simple. They check their work. They write second and third drafts.

Professor : In redrafting, (27-29) they also reduce redundancy.

Jim : Redundancy is a major issue. Listen to this: ‘Second-hand smoke not only affects smokers but also people around them, even loved ones, like wives and children, and it can lead to illness.’

Professor : What would you have written?

Jim : ‘Second-hand smoke can lead to illness.’

Professor : (27-29) Six words instead of 24.

(27-29) Good writers also avoid personal pronouns, like ‘I’ or ‘me’. After all, they’re trying to construct universal arguments, not just give their opinions.

Jim : Some of the essays I read certainly needed more paragraphs. They were hard for me to follow.

Professor : Indeed. An essay is not just about showing what the writer knows; (27-29) it’s about giving the reader an enjoyable experience.

So, when do you two think you’ll be ready to start the theoretical part of your research?

Jim : I’m not sure. I’ll see you next week about that.

Sylvia : I’ve already started, but I’ve got so much to read!

Professor : It seems to me, Sylvia, you’ve collected more than enough essays to analyse, and now you’re in danger of reading too many academic articles. (30) I’d limit the time for your theoretical research to one month. OK?

Sylvia : Thanks. That’s sound advice.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 3.

Narrator : Recording 11.

Section 4. Road Congestion and Market Failure.

You will hear a lecture on road congestion as an example of market failure.

Before you listen, you have 45 seconds to read questions 31 to 40.

Lecturer : Sorry I’m late – the traffic was unbelievable. However, my lateness is pertinent to today’s topic: road congestion as an example of market failure. Next weeks’ examples will be carbon emissions and commercial (31) fishing.

But what is market failure? Broadly speaking, it’s when the free market fails to develop or apportion (32) resources efficiently. A market may fail completely or partially.

In the case of complete failure, resources cannot be allocated to satisfy need or want because there are insufficient incentives for profit-seeking firms to enter the market. Take (33) street lighting: without state intervention, there probably wouldn’t be any, as it’s unlikely private individuals would pay for it themselves. With no revenue generated and no profit earned, no firm would enter the street-lighting market either. That’s why taxes are set aside for public goods.

There are many ways in which partial market failure occurs, but I’d like to focus on (34) over-supply, which is when markets produce too many goods or services. It commonly occurs with demerit goods, like alcohol or tobacco, and with negative externalities.

What are negative externalities? Well, the inability of consumers or producers to account for the effects of their actions on third (35) parties. Road congestion is a classic case.

(36) Oh, let me tell you something I read last night. The speed of traffic in central London has remained fairly constant over the past 100 years. Really? How can that be? Wasn’t most traffic horse-drawn in 1916? Indeed, it was. But the fact remains: in central London, giant four-wheel drives and sleek sports cars travel about as fast as wagons pulled by horses!

Back to business. There are four main ways of dealing with congestion. One, a city increases the amount of road space. Two, it improves public transport. Three, it reduces the demand for travel. Or four, it increases the cost of private travel.

In the case of London, the first measure is counter-productive. There are enormous costs associated with construction, and a long delay between planning and availability. Once built, more roads only encourage more driving, and very soon, congestion rears its ugly head again.

On the surface, improving (37) public transport seems a great idea, but even when it’s reliable, cheap, and convenient, (37) it’s viewed as an inferior good. As incomes rise, most of us leave inferior goods behind. I mean, we used to drink beer; now we drink boutique beer. We used to holiday, locally, at the seaside; now we fly to Thailand!

What about reducing the demand for travel? Unfortunately, no one seems to know how to do this.

The fourth option, raising the cost of private travel has also had limited success. In London, we’ve experienced higher vehicle and fuel taxes, more expensive parking and licence fees, no-parking routes, and a raised driving age, but we’ve kept on driving. Other big cities have taken a different approach. Some Chinese cities limit drivers to four days a week, based on the final number of their licence plate; but, the rich just buy two cars. Sydney and Singapore have tolls on bridges and tunnels, yet people pay up, or drive longer routes to avoid tolls, creating traffic jams elsewhere.

In 2003, London opted for a congestion charge in the central city. Back then, the charge was £5 a day; it’s now £11.50. From its inception, there was a discernible decrease in traffic. Estimates in 2004 by Transport for London, or TFL, were that traffic flow was reduced by almost 20% or 50,000 cars per day. Journeys were 15% faster. The number of bus journeys rose by 15%, and cycle usage by 30. (38) TFL stated that road traffic reduced a further 10% between 2011 and 14. However, a recent report has concluded that, by 2031, (39) congestion will have worsened by a staggering 60% even if strict measures are adopted immediately. It seems as though the cycle is similar to building more roads – a sharp initial improvement, a slower improvement over time, followed by stasis and decline.

So, to conclude: part of the reason for road congestion is an unquantifiable negative externality, exemplary of partial market failure. The free market is incapable of allocating resources efficiently. No matter what authorities do, people continue to drive. On some level, we all know congestion leads to more noise, pollution, accidents, and slower travel times, but cars are cheap and their outlay is fixed. Principally, we drive because we don’t consider our actions in relation to anyone else’s. (40) And, even if we did, I’m not sure most people would care!

Narrator : That is the end of the Listening test.

You now have ten minutes to transfer your answers to your answer sheet.

READING: Passage 1: 1. C; 2. A; 3. B; 4. B; 5. F/False; 6. T/True; 7. F/False; 8. T/True; 9. NG/Not Given; 10. NG/Not Given; 11. T/True; 12. melting point; 13. Furnace; 14. tiny beads. Passage 2: 15. iii; 16. vii; 17. ii; 18. ix; 19. v; 20. A; 21. E; 22. C; 23. B; 24. D; 25. 2/Two billion; 26. 6/Six; 27. Passion and poetry. Passage 3: 28. C; 29. E; 30. B; 31. A; 32. Tentative; 33. bodies; 34. 1/one; 35. cultural; 36. D; 37. G; 38. F; 39. C; 40. A.

The highlighted text below is evidence for the answers above.

If there is a question where ‘Not given’ is the answer, no evidence can be found, so there is no highlighted text.

Uses

In any ordinary kitchen, there are numerous items made from stainless steel, including cutlery, utensils, and appliances. ‘Inox’ or ‘18/10’ may be stamped on the base of a good stainless steel pot: ‘Inox’ is short for the French inoxydable; (1) while 18 refers to the percentage of chromium in the stainless steel, and 10 to its nickel content.

(2) In hospitals, laboratories and factories, stainless steel is used for many instruments and pieces of equipment because it can easily be sterilised, and it remains relatively bacteria-free, thus improving hygiene. Since it is mostly rust-free, stainless steel also does not need painting, so proves cost-effective.

(3) As a decorative element, stainless steel has been incorporated in skyscrapers, like the Chrysler Building in New York, and the Jin Mao Building in Shanghai, the latter considered one of the most stunning contemporary structures in China. Bridges, monuments, and sculptures are often stainless steel; and, cars, trains, and aircraft contain stainless steel parts.

Recent alloys

As most pure metals serve little practical purpose, they are often combined or alloyed. Some examples of ancient alloys are bronze (copper + tin) and brass (copper + zinc). Carbon steel (iron + carbon), first made in small quantities in China in the sixth century AD, was produced industrially only in mid-nineteenth-century Europe. Stainless steel, which retains the strength of carbon steel with some added benefits, consists of iron, carbon, chromium, and nickel, and may contain trace elements. (4) Stainless steel is a new invention – Austenitic stainless steel was patented by German engineers in 1912, the same year that Americans created ferritic stainless steel, while Martensitic stainless steel was patented as late as 1919.

Properties

(5) The name, stainless steel, is misleading since, where there is very little oxygen or a great amount of salt, the alloy will, indeed, stain. In addition, stainless steel parts should not be joined together with stainless steel nuts or bolts as friction damages the elements; another alloy, like bronze, or pure aluminium or titanium must be used.

In general, stainless steel does not deteriorate as ordinary (6) carbon steel does, which rusts in air and water. Rust is a layer of iron oxide that forms when oxygen reacts with the iron in carbon steel. Because iron oxide molecules are larger than those of iron alone, they wear down the steel, causing it to flake and eventually snap. Stainless steel, however, contains between 13-26% chromium, and, with exposure to oxygen, forms chromium oxide, which has molecules the same size as the iron ones beneath, meaning they bond strongly to form an invisible film that prevents oxygen or water from penetrating. As a result, the surface of stainless steel neither rusts nor corrodes. Furthermore, if scratched, the protective chromium-oxide layer of stainless steel repairs itself in (7) a process known as passivation, which also occurs with aluminium, titanium, and zinc.

Varieties

There are over 150 grades of stainless steel with various properties, each distinguished by its crystalline structure. (8) Austenitic stainless steel, comprising 70% of global production, is barely magnetic, but ferritic and Martensitic stainless steel function as magnets because they contain more nickel or manganese. Ferritic stainless steel – soft and slightly corrosive – is cheap to produce, and has many applications, while (9) Martensitic stainless steel, with more carbon than the other types, is incredibly strong, so it is used in fighter jet bodies, but is also the costliest to produce.

Recyclability

Stainless steel can be recycled completely, and these days, (11) the average stainless steel object comprises around 60% of recycled material.

Cutting-edge application

In the last few years, 3D printers have become widespread, and stainless steel infused with bronze is the hardest material that a 3D printer can currently use.

In 3D printing, an inkjet head deposits alternate layers of stainless steel powder and organic binder into a build box. After each layer of binder is spread, overhead heaters dry the object before another layer of powder is added. Upon completion of printing, the whole object, still in its build box, is sintered in an oven, which means the object is heated to just below (12) melting point, so the binder evaporates. Next, the porous object is placed in a (13) furnace so that molten bronze can replace the binder. To finish, the object is blasted with (14) tiny beads that smooth the surface.

Appraisal

In less than a century, stainless steel has become essential due to its relatively cheap production cost, its durability, and its renewability. Used in the new manufacturing process of 3D printing, its future looks bright.

Word lists

A As any language learner knows, the acquisition of vocabulary is of critical importance. Grammar is useful, yet communication occurs without it. Consider the utterance: ‘Me station.’ Certainly, ‘I’d like to go to the station’ is preferable, but a taxi driver will probably head to the right place with ‘Me station.’ If the passenger uses the word ‘airport’ instead of ‘station’, however, the journey may well be fraught. Similarly, ‘What time train Glasgow?’ signals to a station clerk that a timetable is needed even though ‘What time does the train go to Glasgow?’ is correct. In both of these requests, nouns – ‘station’, ‘time’, ‘train’, and ‘Glasgow’ – carry most of the meaning; and, generally speaking, foreign-language learners, like infants in their mother tongue, acquire nouns first. Verbs also contain unequivocal meaning; for instance, ‘go’ indicates departure not arrival. Furthermore, ‘Go’ is a common word, appearing in both requests above, while ‘the’ and ‘to’ are the other frequent items. Thus, for a language learner, there may be two necessities: to acquire both useful and frequent words, including some that function grammatically. It is a daunting fact that English contains around half a million words, of which a graduate knows 25,000. So how does a language learner decide which ones to learn?

B (15) The General Service List (20) (GSL), devised by the American, Michael West, in 1953, was one renowned lexical aid. Consisting of 2,000 headwords, each representing a word family, GSL words were listed alphabetically, with definitions and example sentences, while a number alongside each word showed its number of occurrences per five million words, and a percentage beside each meaning indicated how often that meaning occurred. For 50 years, particularly in the US, the GSL wielded great influence: graded readers and other materials for primary schools were written with reference to it, and American teachers of English as a foreign language (EFL) relying heavily upon it.

C (16) Understandably, West’s 1953 GSL has been updated several times because, firstly, his list contained archaisms such as ‘shilling’, while lacking words that existed in 1953 but which were popularised later, like ‘drug’, ‘OK’, ‘television’, and ‘victim’. Naturally, his list did not contain neologisms such as ‘email’. (23) However, around 80% of West’s original inclusions were still considered valid, according to researchers Billuro lu and Neufeld (2005). Secondly, (22) what constituted a headword and a word family in the West’s GSL was not entirely logical, and rules for this were formulated by Bauer and Nation (1995). Thirdly, technological advance has meant that billions of words can now be analysed by computer for frequency, context, and regional variation. West’s frequency data was based on a 2.5-million-word corpus (24) drawn from research by Thorndike and Lorge (1944), and some of it was unreliable. A 2013 incarnation of the GSL, called the New General Service List (NGSL), used a 273-million-word subsection of the Cambridge English Corpus (24) (CEC), and research indicates this list provides a higher degree of coverage than West’s.

lu and Neufeld (2005). Secondly, (22) what constituted a headword and a word family in the West’s GSL was not entirely logical, and rules for this were formulated by Bauer and Nation (1995). Thirdly, technological advance has meant that billions of words can now be analysed by computer for frequency, context, and regional variation. West’s frequency data was based on a 2.5-million-word corpus (24) drawn from research by Thorndike and Lorge (1944), and some of it was unreliable. A 2013 incarnation of the GSL, called the New General Service List (NGSL), used a 273-million-word subsection of the Cambridge English Corpus (24) (CEC), and research indicates this list provides a higher degree of coverage than West’s.

D (17) A partner to the NGSL is the 2013 New Academic Word List (NAWL) with 2,818 headwords – a modification of (21) Averill Coxhead’s 2000 AWL. The NAWL excludes NGSL words, focusing on academic language, but, nevertheless, items in it are generally serviceable – they are merely not used often enough to appear in the NGSL. An indication of the difference between the two lists can be seen in just four words: the NGSL begins with ‘a’ and ends with ‘zonings’, whereas ‘abdominal’ and ‘yeasts’ open and close the NAWL.

E (18) Over time, linguistics and EFL have become more dependent upon computerized statistical analysis, and large bodies of words have been collected to aid academics, teachers, and learners. One such body, known by the Latin word for body, ‘corpus’, is the CEC, created at Cambridge University in the UK. This well-known collection has (25) two billion words of written and spoken, formal and informal, British, American, and other Englishes. Continually updated, its sources are very wide indeed – far wider than West’s. Although the CEC is one of many English-language corpora, it is not the largest, but it was the one chosen by the creators of the NGSL and the NAWL.

F (19) Still, a learner cannot easily access corpora, and even though the NGSL and NAWL are free online, a learner may not know how best to use them. Linguists have demonstrated that words should be learnt in a context (not singly, not alphabetically); that items in the same lexical set should be learnt together; that it takes at least (26) six different sightings or hearings to learn one item; that written language differs significantly from spoken; and, that concrete language is easier to acquire than abstract. Admittedly, a list of a few thousand words is not so hard to learn, but language learning is not only about frequency and utility, but also about (27) passion and poetry. Who cares if a word you like isn’t in the top 5,000? If you like it or the way it sounds, you’re likely to learn it. And, if you use it correctly, at least your IELTS examiner will be impressed.

World heritage designation

Almost all cultures raise monuments to their own achievements or beliefs, and preserve artefacts and built environments from the past.

There has been considerable interest in saving cultural sites valuable to all humanity since the 1950s. In particular, an international campaign to relocate pharaonic treasures from an area in Egypt where the Aswan Dam would be built was highly successful, with more than half the project costs borne by 50 different countries. (31) Later, similar projects were undertaken to save the ruins of Mohenjoh-daro in Pakistan and the Borobodur Temple complex in Indonesia.

(30) The idea of listing world heritage sites (WHS) that are cultural or natural was proposed jointly by an American politician, Joseph Fisher, and a director of an environmental agency, Russell Train, at a White House conference in 1965. These men suggested a programme of cataloguing, naming, and conserving outstanding sites, under what became the World Heritage Convention, adopted by UNESCO* in November 1972, and effective from December 1975. Today, 191 states and territories have ratified the convention, making it one of the most inclusive international agreements of all time. The UNESCO World Heritage Committee, composed of representatives from 21 UNESCO member states and international experts, administers the programme, albeit with a limited budget and few real powers, unlike other international bodies, like the World Trade Organisation or the UN Security Council.

In 2014, there were 1,007 WHS around the world: 779 of them, cultural; 197 natural; and, 31 mixed properties. (28) Italy, China, and Spain are the top three countries by number of sites, followed by Germany, Mexico, and India.

Legally, each site is part of the territory of the state in which it is located, and maintained by that entity, but as UNESCO hopes sites will be preserved in countries both rich and poor, it provides some financial assistance through the World Heritage Fund. Theoretically, WHS are protected by the Geneva Convention, which prohibits acts of hostility towards historic monuments, works of art, or places of worship.

Certainly, WHS have encouraged appreciation and tolerance globally, as well as proving a boon for local identity and the tourist industry. Moreover, diversity of plant and animal life has generally been maintained, and degradations associated with mining and logging minimised.

Despite good intentions, significant threats to WHS exist, especially in the form of conflict. The Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo is one example, where militias kill white rhinoceros, selling their horns to purchase weapons; and, in 2014, Palmyra – a Roman site in northern Syria – was badly damaged by a road built through it, as well as by shelling and looting. In fact, theft is a common problem at WHS in under-resourced areas, while pollution, nearby construction, or natural disasters present further dangers.

But most destructive of all is mass tourism. The huge ancient city of Angkor Wat, in Cambodia, now has over one million tourists a year, and the nearby town of Siem Reap – a village 20 years ago – boasts an international airport and 300 hotels. (29) Machu Picchu in Peru has been inundated by visitors to the point where it may now be endangered. Commerce has altered some sites irrevocably. Walkers along the Great Wall near Beijing are hassled by vendors flogging every kind of item, many unrelated to the wall itself, and extensive renovation has given the ancient wonder a Disneyland feel.

In order for a place to be listed as a WHS, it must undergo a rigorous application process. Firstly, a state takes an inventory of its significant sites, which is called a (32) Tentative List, from which sites are put into a Nomination File. Two independent international (33) bodies, the International Council on Monuments and Sites, and the World Conservation Union, evaluate the Nomination File, and make recommendations to the World Heritage Committee. Meeting once a year, this committee determines which sites should be added to the World Heritage List by deciding that a site meets at least (34) one criterion out of ten, of which six are (35) cultural, and four are natural.

In 2003, a second convention, effective from 2008, was added to the first. (36) The Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage has so far been ratified by 139 states – a notable exception being the US. Aiming to protect traditions rather than places, 267 elements have already been enshrined, including: Cambodia’s Royal Ballet; the French gastronomic meal; and, watertight-bulkhead technology of Chinese junks.

(37) The World Heritage Committee hopes that the states that agree to list such elements will also promote and support them, although, once again, commercialisation is problematic. For instance, after the French gastronomic meal was listed in 2010, numerous French celebrity chefs used the designation in advertising, and UNESCO debated delisting the element. (38) The US has chosen not to sign the second convention due to implications to intellectual property rights. As things stand, with the first treaty, the US has far fewer nominated sites than its neighbour Mexico, partly because some Mexican sites are entire towns or city centres, and the US has no desire for its urban planning to be restricted by world-heritage status. (39) St Petersburg, in Russia, which has its entire historic centre as a WHS, introduced strict planning regulations to maintain its elegant 18th-century appearance, only to discover thousands of minor infringements by owners preferring to do what they pleased with their properties. With intangible elements, changes over time, due to modernisation or globalization, may be greater than those threatening buildings. (40) Opponents of the second convention believe traditions should not be frozen in time, and are equally unconcerned if traditions dwindle or die.

Although the 1972 World Heritage Convention lacks teeth, and many of its sites are suffering, and although the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage has proven less popular, it would seem that the overall performance of these two instruments has been very good.

WRITING: Task 1

Pancha Village changed markedly from 2005 to 2015. While both sides of its main road were built up in 2005, they were more so a decade later. Only two totally new buildings in the pagoda complex, one in the school, and some stalls in the market had been added by 2015, but redevelopment and technological improvement were noticeable.

What, in 2005, was solely a primary school, was, in 2015, both a primary and a secondary school. The two school buildings that were originally huts were rebuilt in concrete, one new building was constructed, and a flagpole erected in the playground.

Technological improvements in 2015 included: a sealed road with lane markings, a pedestrian crossing, and signage. Poles along the road brought electricity to the village. Two large antennae for mobile communications had been built next to the market, and four houses that formerly had only had TV aerials now boasted satellite dishes. The road had been widened, and there was three vehicles on it.

The only sign of destruction in 2015 was the removal of two houses near the pagoda. (171 words)

Task 2

Today, there is an imbalance in the populations of developed countries. Declining birth rates and low immigration mean there are many more people over 65 years of age than those below. Despite a high standard of living, the ageing population is causing social and economic problems.

An ageing population, with many medical needs, may be a drain on health services. Where a developed country has a subsidised health service, this means that public funds are channelled more towards the aged than towards younger people. As a result, there may be reduced public funding of sectors such as education.

Those over 65 are usually eligible for state pensions, which they see as their right because they paid taxes when employed. However, this can cause tension between the young and the old.

Employment, too, is another area where the aged often benefit at the expense of those younger. Elderly people who are able, may work much longer than those who retired at 65. Some work from need; others because they are mentally, and in some cases physically, fit enough to continue. In the past, the older generation made way for the younger ones.

I suggest the following solutions. Firstly, through technological and medical advances, health care of the aged will continue to improve, making them less of a burden. To ensure that the public is not responsible for others’ health care, a national health insurance scheme should be compulsory.

Secondly, the pension age should be raised to match the fitness of the aged. Since many over 65 are already still working, this should not be too problematic. Also if a personal pension scheme is made obligatory from the age of 21, then later aged generations will not be a burden on the young.

Lastly, if more immigrants are encouraged to enter a developed country, they could not only fill in the generation gap, but also bring skills that may be lost as the workforce ages. Mechanics, technicians, doctors, nurses, engineers, and teachers all would be beneficial. (334 words)

Narrator : Recording 12.

Test 2.

Part 1 of the Speaking test.

Listen to a candidate who is likely to be awarded a Nine answering questions in Part 1 of the Speaking test.

Examiner : Good afternoon. My name is Lucy. Could you tell me your full name please?

Candidate : Gao Nan, but my English name is Stephen.

Examiner : And where are you from, Stephen?

Candidate : Tianjin – a big city not far from Beijing.

Examiner : Could I check your ID, please?

Thanks.

First of all, Stephen, I’d like to ask you a few questions about yourself.

Could you tell me about the accommodation you’re currently living in?

Candidate : Right now, I’m living with my cousin in a house in Hillsdale. We’re sharing with three other people – another guy from China, and a married couple from Iran.

Examiner : And do you have a favourite part of the house?

Candidate : I’d say my bedroom or perhaps the back yard. Yeah – the back yard. We’ve got a small yard that’s mostly brick. I like to sit out there in a rusty old chair. It’s peaceful. I like to look at the blue sky. You almost never see blue sky in Tianjin.

Examiner : Do you think you’ll stay where you’re living for a while?

Candidate : I guess so. It’s close to the uni I’m hoping to go to next year, and it’s great for shopping and public transport.

Examiner : Now, let’s move on to talk about hats and caps.

Candidate : Hats and caps?

Examiner : Yes, hats and caps.

Do you ever wear a hat or a cap?

Candidate : Not really. Not in Sydney. I know the sun’s really bad here, and I occasionally wear a baseball cap in summer, but otherwise, no.

Examiner : Why do some people wear hats or caps?

Candidate : Well, to keep the sun off, to cover up their bald patches – I had an uncle who did that – and, of course in Tianjin it snows in winter, so lots of people wear hats then. I’ve also noticed that most schoolchildren in Sydney wear hats as part of their uniform.

Examiner : Do you think headgear was more popular in the past?

Candidate : Probably.

In my grandfather’s photos from the 1960s, lots of people in Tianjin are wearing hats. In the 1970s, there was a cap, like the one Chairman Mao wore, that was kind of obligatory.

Examiner : Why was headgear more popular in the past?

Candidate : I’m not sure exactly. Perhaps hats showed your occupation or your social status, or, as I said, they were obligatory. You can still see old guys in Xinjiang – that’s a western province of China – wearing tall black woollen hats because they’re farmers. And some headgear belongs to certain ethnic groups.

Examiner : Now, let’s talk about time: When was the last time you were rather late?

Candidate : Actually, I’m almost always on time, but a few weeks ago, my cousin and I drove up to the Blue Mountains—we’d been invited to a party at Mount Wilson. We’ve both got Google maps on our phones, but we still got lost.

By the time we found the party, almost everyone else’d gone home.

Examiner : How do you feel when other people are late?

Candidate : Depends on the situation. I don’t mind if it’s a friend or a relative, and they send a text or something. But at work, it does annoy me because I’m not paid extra to do the work of a latecomer.

Examiner : Do you think people these days have enough time?

Candidate : Yes, I do. They say they don’t, but everyone I know who makes a schedule and sticks to it, or makes some kind of long-term plan manages, pretty much, to fit everything in. I believe you can make time if you want to.

Examiner : How do you think children perceive time?

Candidate : How do I think children perceive time? Well, some children are impatient. And some children think the future is never gonna happen. I know when I was a kid I couldn’t believe I’d get to high school, let alone university.

Maybe time goes more slowly for children?

Narrator : Recording 13.

Part 2 of the Speaking test.

Listen to Stephen’s two-minute topic.

Examiner : In this part, Stephen, I’m going to give you a topic for you to speak about for two minutes. Before you speak, you’ll have one minute to prepare, and you can write some notes on this paper if you like. Do you understand?

Candidate : Sure.

Examiner : Here’s your topic: I’d like you to tell me about someone you think is attractive.

Narrator : One minute later.

Examiner : OK?

Remember, you’re going to speak for two minutes. Don’t worry if I interrupt you to tell you when your time is up.

Could you start speaking now, please, Stephen?

Candidate : Right. Well, I’m going to tell you about my mother. Perhaps that’s kinda corny, but when I look at her in photos taken when she was a teenager or in her twenties, she was, in fact, very attractive.

Firstly, she’s quite tall. Her family comes from Heilongjiang Province, where there are quite a lot of tall people. Her own mother was taller than average for a woman of her time.

So, my mother’s tall, and she’s always had a good figure. Even now, in her fifties, she’s slim and fit. She’s always maintained excellent posture, which I put down to the fact that she’s been a dancer since she was a child.

She’s tall, she’s got a good figure, and, most noticeably, she’s got a lovely smile. Her facial features aren’t classically beautiful or completely regular, but that’s also part of her charm. When she smiles, she’s got two little dimples in her cheeks, and her nickname was ‘Dimple’ when she was a kid. She’s got very narrow eyes and high cheekbones and a small chin. Her face is sort of triangular.

Once, when I was about twelve, we were on an overnight train trip, and a woman sharing our carriage insisted my mother looked like a famous singer. It turned out that when my father first met my mother, he’d thought the same.

But, in my eyes, what’s particularly attractive about my mother is her gentleness. I mean, I haven’t been what you’d call a model son. I scored pretty badly in the Gaokao – that’s the Chinese university entrance exam – and I took almost five years to get my bachelor’s degree. But, in all that time, she still believed in me.

What else? Oh, the way she dresses. In the past, our family didn’t have much money, and Mum hardly ever bought any new clothes for herself, but I remember she always looked elegant in comparison to the mothers of my school friends. Even today, she usually wears fitted dresses in plain colours – not patterns, whereas lots of Chinese women of her generation like floral clothes. Yes, I’d say she’s got flair.

Examiner : Thank you.

Narrator : Recording 14.

Part 3 of the Speaking test.

Listen to the rest of Stephen’s test.

Examiner : So you’ve told me about someone you think is attractive, and now I’d like to discuss some more general questions related to beauty.

First of all: Physical appearance and societal pressure.

Do you think these days, there’s a lot of pressure to conform to a norm, or to look beautiful?

Candidate : Absolutely.

Think of all the gyms and products that are meant to make you thin in some places and muscular in others. We’re bombarded with these products.

Before I came to Sydney, I was working in South Korea, and I’ve never seen anyone so obsessed with plastic surgery as the Koreans. Women and men. My boss’d had about five procedures, and he claimed that the only way to get promoted was to look more handsome than the other guy.

Examiner : Do you think he was right?

Candidate : Maybe.

Examiner : So, what are some of the dangers of this pressure to be attractive?

Candidate : Well, there’ll be people who are less physically attractive who find it hard to get jobs even though they’ve got the skills, and that’s a waste for society. In Busan, I met people who’d borrowed money from banks to pay for their plastic surgery, and I’m sure that money could’ve been better invested elsewhere.