Prepare some snacks and drinks.

Prepare some snacks and drinks.

Find a reliable stopwatch or clock.

Find a reliable stopwatch or clock.

Use an electronic device to access the audio at www.mheIELTS6practicetests.com.

Use an electronic device to access the audio at www.mheIELTS6practicetests.com.

Find a place where you can work with no interruptions for four hours – three for this whole test + one to go through the answers.

Find a place where you can work with no interruptions for four hours – three for this whole test + one to go through the answers.

Firstly, tear out the Test 3 Listening / Reading Answer Sheet at the back of this book.

The Listening test lasts for about 20 minutes.

Write your answers on the pages below as you listen. After Section 4 has finished, you have ten minutes to transfer your answers to your Listening Answer Sheet. You will need to time yourself for this transfer.

After checking your answers on pp 134-138, go to page 9 for the raw-score conversion table.

PLAY RECORDING #15.

PLAY RECORDING #15.

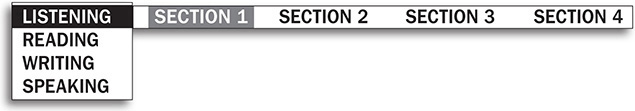

SECTION 1 Questions 1-10

INSURANCE

Complete the form below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS OR A NUMBER for each answer.

Questions 7-8

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

7 The woman will buy

A a new car.

B an old car.

C a new motorbike.

8 The woman does not want to insure her vehicle with a Multi-saver policy because it

A benefits homeowners.

B has too many conditions.

C is rather expensive.

Choose TWO letters, A-E.

Which TWO of the following relate to the Top Cover policy?

A It is cheaper than many other policies.

B There is a stand-down period before it takes effect.

C It covers storm damage.

D It covers vehicles of any age.

E It includes an agreement on the value of a holder’s vehicle.

PLAY RECORDING #16.

PLAY RECORDING #16.

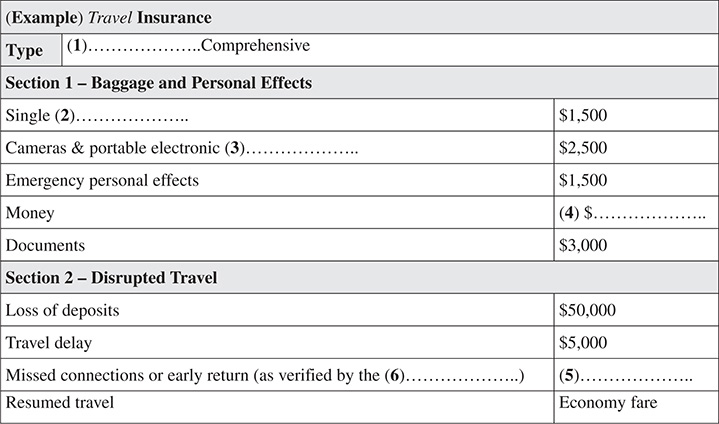

SECTION 2 Questions 11-20

TOURING DEVONPORT ON A SEGWAY

Questions 11-16

Complete the sentences below.

Write NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER for each answer.

11 The company does not allow children, pregnant women, or people recovering from………………..to ride Segways.

12 The Segway tour of Devonport lasts for……………….. .

13 Unlike a cyclist, a Segway rider barely needs………………..to remain in motion.

14 A Segway weighs……………….. .

15 Accidents happen due to jumping off, or jerking instead of………………..to move the Segway.

16 The gyroscope monitors a rider’s……………….., and adjusts the post to maintain balance.

Questions 17-20

Label the map below.

Write the correct letter, A-I, next to questions 17-20.

17 North Head

………………..

18 French Café

………………..

19 Yacht club

………………..

20 Remains from pre-European settlement

………………..

PLAY RECORDING #17.

PLAY RECORDING #17.

SECTION 3 Questions 21-30

STUDY OPTIONS

Questions 21-24

Answer the questions below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS for each answer.

21 What was Professor Anderson attending in Massachusetts and New York?

………………..………………..

22 What mark did Rangi receive for Classical Mechanics?

………………..………………..

23 Which degree has Rangi decided to abandon?

………………..………………..

24 How does Professor Anderson describe the Science Faculty?

………………..………………..

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

25 A benefit of Rangi’s decision is that he will

A finish his degree earlier.

B improve his writing style.

C receive higher marks.

26 Professor Anderson thinks the claims of some lecturers are

A boastful.

B doubtful.

C critical.

27 Rangi is disappointed because he

A can’t afford to study abroad.

B will have to work in a bar again.

C won’t be going to Europe.

28 The professor offers Rangi

A a part-time job in her lab.

B help with his laser experiments.

C supervision of his master’s degree.

29 In the professor’s opinion, Rangi is …… to win a scholarship.

A not so likely

B quite likely

C highly likely

30 Rangi feels …… by the end of the conversation.

A a little apprehensive

B relieved and grateful

C thrilled but nervous

PLAY RECORDING #18.

PLAY RECORDING #18.

SECTION 4 Questions 31-40

THE UGLY FRUIT MOVEMENT

Questions 31-35

Choose FIVE answers from the box, and write the correct letter, A-H, next to questions 31-35.

A Consumers like food that tastes as good as it looks.

B Every year, approximately 40% of food fit for humans is wasted.

C Harvesting and processing need substantial improvement.

D Food wastage causes an annual loss of $870 million.

E Food production uses 80% of available fresh water.

F Use-by-date labelling is being challenged.

G Supermarkets sell fruit and vegetables in virtually any condition.

H Newspapers mocked strict European Union regulations.

31 Globally………………..

32 In the US………………..

33 In Bolivia………………..

34 In Portugal………………..

35 In the UK………………..

Questions 36-38

Complete the sentences below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS OR A NUMBER for each answer.

36 Portugal was affected by a……………crisis.

37 Isabel Soares hopes to subvert notions about what food is…………… .

38 José Dias used to dump a……………of his tomato crop before he sold to Fruta Feia.

39 Tomatoes bought by members of Fruta Feia cost……………than those at supermarkets.

Question 40

40 What does the lecturer think of Fruta Feia?

A He supports it wholeheartedly.

B He supports it with some reservations.

C He does not really support it.

Firstly, turn over the Test 3 Listening Answer Sheet you used earlier to write your Reading answers on the back.

The Reading test lasts exactly 60 minutes.

Certainly, make any marks on the pages below, but transfer your answers to the answer sheet as you read since there is no extra time at the end to do so.

After checking your answers on pp 139-141, go to page 9 for the raw-score conversion table.

PASSAGE 1

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13, based on Passage 1 below.

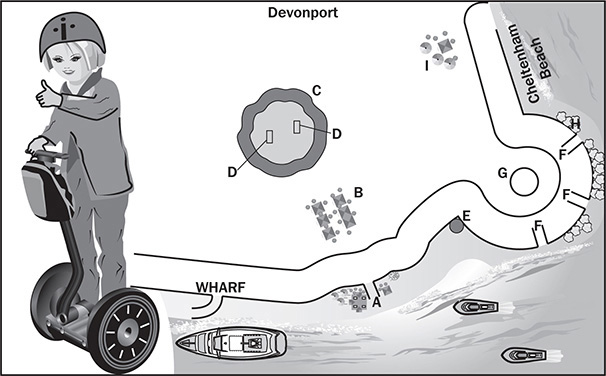

A When Gabriel García Márquez died in 2014, he was mourned around the world, as readers recalled his 1967 novel, One hundred years of solitude, which has sold more than 25 million copies, and led to Márquez’s receipt of the 1982 Nobel Prize for Literature.

B Born in 1927, in a small town on Colombia’s Caribbean coast called Aracataca, Márquez was immersed in Spanish, black, and indigenous cultures. In such remote places, religion, myth, and superstition hold sway over logic and reason, or perhaps operate as parallel belief systems. Certainly, the ghost stories told by his grandmother affected the young Gabriel profoundly, and a pivotal character in his 1967 epic is indeed a ghost.

Márquez’s family was not wealthy: there were twelve children, and his father worked as a postal clerk, a telegraph operator, and an occasional pharmacist. Márquez spent much of his childhood in the care of his grandparents, which may account for the main character in One hundred years of solitude resembling his maternal grandfather. Although Márquez left Aracataca aged eight, the town and its inhabitants never seemed to leave him, and suffuse his fiction.

C One hundred years of solitude was the fourth of fifteen novels, but Márquez was an equally passionate and prolific journalist.

In Bogotá, during his twenties and thirties, Márquez experienced La Violencia, a period of great political and social upheaval, when around 300,000 Colombians were killed. Certainly, life was never safe for journalists, and after writing an article on corruption in the Colombian navy in 1955, Márquez was forced to flee to Europe. Incidentally, in Paris, he discovered that European culture was not richer than his own, and he was disappointed by Europeans who were patronising towards Latin Americans. On return to the southern hemisphere, Márquez wrote for Venezuelan newspapers and the Cuban press agency.

D In terms of politics, Márquez was leftwing. In Chile, he campaigned against the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet; in Venezuela, he financed a political party; and, in Nicaragua, he defended revolutionaries. He considered Fidel Castro, the President of Cuba, as a dear friend. Since the US was hostile towards Castro’s communist regime, which Márquez supported, the writer was banned from visiting the US until invited by President Clinton in 1995. The novels of Márquez are imbued with his politics, but this does not prevent readers from enjoying a good yarn.

E Márquez maintained that in Latin America so much that is real would seem fantastic elsewhere, while so much that is magical seems real. He was an exponent of a genre known as Magical Realism.

‘If you can explain it,’ said the Mexican critic, Luis Leal, ‘then it’s not Magical Realism.’ This demonstrates the difficulty of determining what the genre encompasses and which writers belong to it.

The term Magical Realism is usually applied to literature, but its first use was probably in 1925, when a German art critic reviewed paintings similar to those of Surrealism.

Many critics define Magical Realism by what it is not. Realism describes lives that could be real; Magical Realism uses the detail and the tone of a realist work, but includes the magical as though it were real. The ghosts in One hundred years of solitude and in the American Toni Morrison’s Beloved are presented by their narrators as normal, so readers accept them unhesitatingly. Likewise, a character can live for 200 years in a Magical Realist novel. Surrealism explores dream states and psychological experiences; Magical Realism does not. Science Fiction describes a new or an imagined world, as in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, but Magical Realism depicts the real world. Nor is Magical Realism fantasy, like Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, in which an ordinary man awakens to find he has transformed into a cockroach. This is because the writer and the reader of that story cannot decide whether to ascribe natural or supernatural causes to the event. In contrast, in a work by Márquez, the world is both natural and supernatural, both rational and irrational, and this binary nature fascinates readers.

Magical Realism does share some common ground with post-modernism since the acts of writing and reading are self-reflexive. A narrative may not be linear, but may double back on itself, or be discontinuous, and the notion of character is more illusive than in other genres.

Naturally, some of these elements disturb a reader although the enormous success of One hundred years of solitude and the hundreds of other Magical Realist works from authors as far apart as Norway, Nigeria, and New Zealand would seem to belie it.

F Latin America has had a long history of conquest, revolution, and dictatorship; of hunger, poverty, and chaos, yet, at the same time, is endowed with rich cultures, with warm, emotional people, many of whom, like Márquez, remain optimistically utopian. Gabriel García Márquez has passed away, but his fiction will certainly endure.

Questions 1-7

Passage 1 has six sections, A-F.

Which section contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-F, in boxes 1-7 on your answer sheet.

NB: You may use any letter more than once.

1 Márquez’s background

2 how Márquez felt about Europe

3 influences on Márquez

4 the extent of Márquez’s fame

5 why the US did not welcome Márquez

6 what constitutes a Magical Realist work

7 other writing important to Márquez

Complete the summary below using the dates or words, A-L, below.

Write the correct letter, A-L, in boxes 8-13 on your answer sheet.

The genre of Márquez’s fiction is known as Magical Realism, a term first applied to painting in (8) ………………... Magical Realism is often described in negative terms, as not being Realism, Surrealism, Science Fiction, or (9) …………………

In a Magical Realist novel, the world people live in – which is the real world – is described in detail, but magical or (10)……………….. elements intrude. These are treated like real ones, so that a reader (11)……………….. them. For instance, characters live longer than natural lives, and ghosts exist. Time, in a Magical Realist work, may also be (12)……………….. .

Despite requiring a suspension of disbelief by readers, Magical Realism has enjoyed great success, with writers from all over the world (13)……………….. the style.

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-27, based on Passage 2 below.

For as long as there have been financial markets, there have been financial crises. Most economists agree, however, that from 1994 to 2013 crashes were deeper and the resultant troughs longer-lasting than in the 20-year period leading up to 1994. Two notable crashes, the Nifty Fifty in the mid-1970s and Black Monday in 1987, had an average loss of about 40% of the value of global stocks, and recovery took 240 days each, whereas the Dot-com and credit crises, post-1994, had an average loss of about 52%, and endured for 430 days. What economists do not agree upon is why recent crises have been so severe or how to prevent their recurrence.

John Coates, from the University of Cambridge in the UK and a former trader for Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank, believes three separate but related phenomena explain the severity. The first is dangerous but predictable risk-taking on the part of traders. The second is a lack of any risk-taking when markets become too volatile. (Coates does not advocate risk-aversion since risk-taking may jumpstart a depressed market.) The last is a new policy of transparency by the US Federal Reserve – known as the Fed – that may have encouraged stock-exchange complacency, compounding the dangerous risk-taking.

Many people imagine a trader to have a great head for maths and a stomach for the rollercoaster ride of the market, but Coates downplays arithmetic skills, and doubts traders are made of such stern stuff. Instead, he draws attention to the physiological nature of their decisions. Admittedly, there are women in the industry, but traders are overwhelmingly male, and testosterone appears to affect their choices.

Another common view is that traders are greedy as well as thrill-seeking. Coates has not researched financial incentive, but blood samples taken from London traders who engaged in simulated risk-taking exercises for him in 2013 confirmed the prevalence of testosterone, cortisol, and dopamine – a neurotransmitter precursor to adrenalin associated with raised blood pressure and sudden pleasure.

Certainly anyone faced with danger has a stress response involving the body’s preparation for impending movement – for what is sometimes called ‘Fight or flight’, but, as Coates notes, any physical act at all produces a stress response: even a reader’s eye movement along words in this line requires cortisol and adrenalin. Neuroscientists now see the brain not as a computer that acts neutrally, involved in a process of pure thought, but as a mechanism to plan and carry out movement, since every single piece of information humans absorb has an attendant pattern of physical arousal.

For muscles to work, fuel is needed, so cortisol and adrenalin employ glucose from other muscles and the liver. To burn the fuel, oxygen is required, so slightly deeper or faster breathing occurs. To deliver fuel and oxygen to the body, the heart pumps a little harder and blood pressure rises. Thus, the stress response is a normal part of life, as well as a resource in fighting or fleeing. Indeed, it is a highly pleasurable experience in watching an action movie, making love, or pulling off a multi-million-dollar stock-market deal.

Cortisol production also increases during exposure to uncertainty. For example, people who live next to a train line adjust to the noise of passing trains, but visitors to their home are disturbed. The phenomenon is equally well-known of anticipation being worse than an event itself: sitting in the waiting room thinking about a procedure may be more distressing than occupying the dentist’s chair and having one. Interestingly, if a patient does not know approximately when he or she will be called for that procedure, cortisol levels are the most elevated of all. This appeared to happen with the London traders participating in some of Coates’ gambling scenarios.

When there is too much volatility in the stock market, Coates suspects adrenaline levels decrease while cortisol levels increase, explaining why traders take fewer risks at that time. In fact, typically traders freeze, becoming almost incapable of buying or selling anything but the safest bonds. In Coates’ opinion, the market needs investment as it falls and at rock bottom – at such times, greed is good.

The third matter – the behaviour of the Fed – Coates thinks could be controlled, albeit counter-intuitively. Since 1994, the US Federal Reserve has adopted a policy called Forward Guidance. Under this, the public is informed at regular intervals of the Fed’s plans for short-term interest rates. Recently, rates have been raised by small but predictable increments. By contrast, in the past, the machinations of the Fed were largely secret, and its interest rates fluctuated apparently randomly. Coates hypothesises this meant traders were on guard and less likely to indulge in wild speculation. In introducing Forward Guidance, the Fed hoped to lower stock and housing prices; instead, before the crash of 2008, the market surged from further risk-taking, like an unleashed pit bull terrier.

There are many economists who disagree with Coates, but he has provided some physiological evidence for both traders’ recklessness and immobilisation, and made the radical proposal of greater opacity at the Fed. Although, as others have noted, we could just let more women onto the floor.

Questions 14-19

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 14-19 on your answer sheet.

14 What do most economists agree about the financial crashes from 1994 to 2013?

A They were the worst global markets had ever experienced.

B Global stocks fell around 40% for a period of 240 days.

C They were particularly acute in the US.

D They were more severe than those between 1974 and 1993.

15 What does John Coates think about risk-taking among stock-market traders?

A It is almost invariably dangerous.

B It was prevalent at Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank.

C It should be regulated by the US Federal Reserve.

D It can sometimes assist a weak market.

16 What are some popular beliefs about traders?

A They are clever, calm, and acquisitive.

B They are usually men who are good at maths.

C They love danger and seek it out.

D They do not deserve their high salaries.

17 What did Coates find in blood samples from London traders in 2013?

A They had high levels of testosterone and dopamine.

B They produced excessive glucose and oxygen.

C They experienced high blood pressure.

D They drank large amounts of alcohol.

18 How do neuroscientists now view the brain?

A As an extraordinary computer.

B As an organ to control movement.

C As the main producer of adrenaline and cortisol.

D As a significant enhancer of pleasure.

19 Why might a person waiting to see a dentist have extremely high cortisol levels?

A He or she may dislike going to the dentist.

B He or she may be worried about the procedure.

C He or she may not have a specific appointment.

D He or she may not be able to afford the consultation.

Questions 20-24

Complete the flowchart below.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 20-24 on your answer sheet.

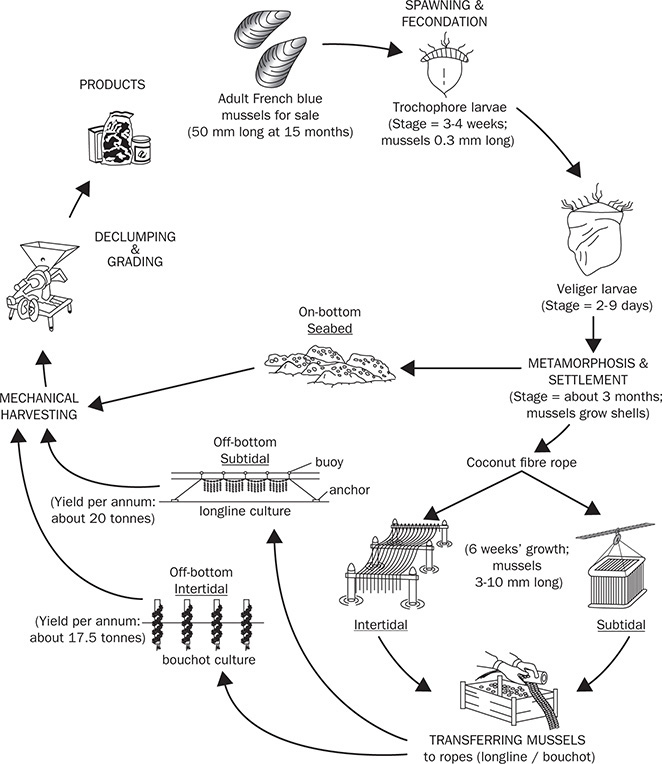

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Passage 2?

In boxes 25-27 on your answer sheet, write:

25 Coates’ views are held by many other economists.

26 Coates’ suggestion of less transparency at the Fed is sound.

27 Raising the number of female traders may solve the problem.

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 28-40, which are based on Passage 3 below.

Aristotle, a 4th-century-BC Greek philosopher, created the Great Chain of Being, in which animals, lacking reason, ranked below humans. The Frenchman, René Descartes, in the 17th century AD, considered animals as more complex creatures; however, without souls, they were merely automatons. One hundred years later, the German, Immanuel Kant, proposed animals be treated less cruelly, which might seem an improvement, but Kant believed this principally because he thought acts of cruelty affect their human perpetrators detrimentally. The mid-19th century saw the Englishman, Jeremy Bentham, questioning not their rationality or spirituality, but whether animals could suffer irrespective of the damage done to their victimisers; he concluded they could; and, in 1824, the first large organisation for animal welfare, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, was founded in England. In 1977, the Australian, Peter Singer, wrote the highly influential book Animal liberation, in which he debated the ethics of meat-eating and factory farming, and raised awareness about inhumane captivity and experimentation. Singer’s title deliberately evoked other liberation movements, like those for women, which had developed in the post-war period.

More recently, an interest in the cognitive abilities of animals has resurfaced. It has been known since the 1960s that chimpanzees have sophisticated tool use and social interactions, but research from the last two decades has revealed they are also capable of empathy and grief, and they possess self-awareness and self-determination. Other primates, dolphins, whales, elephants, and African grey parrots are highly intelligent too. It would seem that with each new proof of animals’ abilities, questions are being posed as to whether creatures so similar to humans should endure the physical pain or psychological trauma associated with habitat loss, captivity, or experimentation. While there may be more laws protecting animals than 30 years ago, in the eyes of the law, no matter how smart or sentient an animal may be, it still has a lesser status than a human being.

Steven Wise, an American legal academic, has been campaigning to change this. He believes animals, like those listed above, are autonomous – they can control their actions, or rather, their actions are not caused purely by reflex or from innateness. He wants these animals categorized legally as non-human persons because he believes existing animal-protection laws are weak and poorly enforced. He famously quipped that an aquarium may be fined for cruel treatment of its dolphins but, currently, the dolphins can’t sue the aquarium.

While teaching at Vermont Law School in the 1990s, Wise presented his students with a dilemma: should an anencephalic baby be treated as a legal person? (Anencephaly is a condition where a person is born with a partial brain and can breathe and digest, due to reflex, but otherwise is barely alert, and not autonomous.) Overwhelmingly, Wise’s students would say ‘Yes’. He posed another question: could the same baby be killed and eaten by humans? Overwhelmingly, his students said ‘No’. His third question, always harder to answer, was: why is an anencephalic baby legally a person yet not so a fully functioning bonobo chimp?

Wise draws another analogy: between captive animals and slaves. Under slavery in England, a human was a chattel, and if a slave were stolen or injured, the thief or violator could be convicted of a crime, and compensation paid to the slave’s owner though not to the slave. It was only in 1772 that the chief justice of the King’s Bench, Lord Mansfield, ruled that a slave could apply for habeas corpus, Latin for: ‘You must have the body’, as free men and women had done since ancient times. Habeas corpus does not establish innocence or guilt; rather, it means a detainee can be represented in court by a proxy. Once slaves had been granted habeas corpus, they existed as more than chattels within the legal system although it was another 61 years before slavery was abolished in England. Aside from slaves, Wise has studied numerous cases in which a writ of habeas corpus had been filed on behalf of those unable to appear in court, like children, patients, prisoners, or the severely intellectually impaired. In addition, Wise notes there are entities that are not living people that have legally become non-human persons, including: ships, corporations, partnerships, states, a Sikh holy book, some Hindu idols and the Wanganui River in New Zealand.

In conjunction with an organisation called the Non-human Rights Project (NhRP), Wise has been representing captive animals in US courts in an effort to have their legal status reassigned. Thereafter, the NhRP plans to apply, under habeas corpus, to represent the animals in other cases. Wise and the NhRP believe a new status will discourage animal owners or nation states from neglect or abuse, which current laws fail to do.

Richard Epstein, a professor of Law at New York University, is a critic of Wise’s. His concern is that if animals are treated as independent holders of rights there would be little left of human society, in particular, in the food and agricultural industries. Epstein agrees some current legislation concerning animal protection may need overhauling, but he sees no underlying problem.

Other detractors say that the push for personhood misses the point: it focuses on animals that are similar to humans without addressing the fundamental issue that all species have an equal right to exist. Thomas Berry, of the Gaia Foundation, declares that rights do not emanate from humans but from the universe itself, and, as such, all species have the right to existence, habitat, and role (be that predator, plant, or decomposer). Dramatically changing human behaviour towards other species is necessary for their survival – and that doesn’t mean declaring animals as non-human persons.

To date, the NhRP has not succeeded in its applications to have the legal status of chimpanzees in New York State changed, but the NhRP considers it some kind of victory that the cases have been heard. Now, the NhRP can proceed to the Court of Appeals, where many emotive cases are decided, and where much common law is formulated.

Despite setbacks, Wise doggedly continues to expose brutality towards animals. Thousands of years of perceptions may have to be changed in this process. He may have lost the battle, but he doesn’t believe he’s lost the war.

Questions 28-33

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 28-33 on your answer sheet.

28 Why did Aristotle place animals below human beings?

A He doubted they behaved rationally.

B He thought them less intelligent.

C He considered them physically weaker.

D He believed they did not have souls.

29 Why did Kant think humans should not treat animals cruelly?

A Animals were important in agriculture.

B Animals were used by the military.

C Animals experience pain in the same way humans do.

D Humans’ exposure to cruelty was damaging to themselves.

30 What concept of animals did Bentham develop?

A The existence of their suffering

B The magnitude of their suffering

C Their surprising brutality

D Their surprising spirituality

31 Where and when was the RSPCA founded?

A In Australia in 1977

B In England in 1824

C In Germany in 1977

D In the US in 1824

32 Why might Singer have chosen the title Animal liberation for his book?

A He was a committed vegetarian.

B He was concerned about endangered species.

C He was comparing animals to other subjugated groups.

D He was defending animals against powerful lobby groups.

33 What has recent research shown about chimpanzees?

A They have equal intelligence to dolphins.

B They have superior cognitive abilities to most animals.

C They are rapidly losing their natural habitat.

D They are far better protected now than 30 years ago.

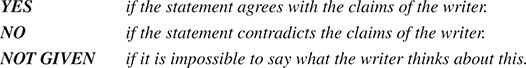

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 34-40 on your answer sheet.

The Writing test lasts for 60 minutes.

Task 1

Spend about 20 minutes on this task.

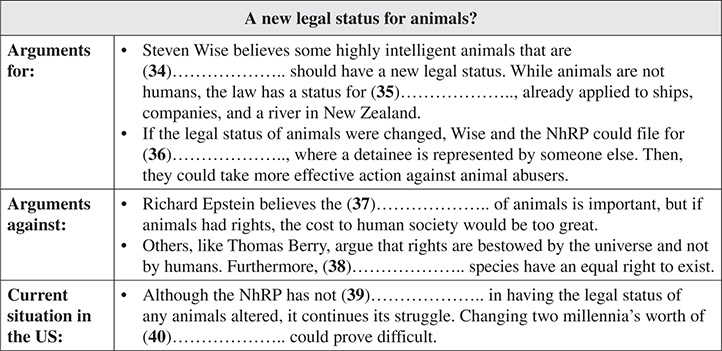

The diagram belows shows French blue mussel culture.

Write a summary of the information. Select and report the main features, and make comparisons where necessary.

Write at least 150 words.

Task 2

Spend about 40 minutes on this task.

Write about the following topic:

Plagiarism* in all kinds of writing is becoming more frequent.

Why is this happening?

Some people think plagiarism causes problems, but others accept it. Discuss both views, and give your own opinion.

Provide reasons for your answer, including relevant examples from your own knowledge or experience.

Write at least 250 words.

PART 1

How might you answer the following questions?

1 Could you tell me what you’re doing at the moment: are you working or studying?

2 What do you find easy or difficult about your job?

3 Do you think you’ll stay in the same job for a long time?

4 Now, let’s talk about music. Have you ever played a musical instrument?

5 Do you think some people are naturally good at music?

6 Could you compare performing in a choir or orchestra with performing alone?

7 Do you agree or disagree: the music industry these days is less about music than about style?

8 Let’s move on to talk about visiting people. How often do you have visitors to your home? What do you do?

9 How do you feel about staying the night at the homes of friends or relatives?

10 How has visiting others changed in your country in the last 20 years?

PART 2

How might you speak about the following topic for two minutes?

I’d like you to tell me about a game (not a sport) you used to play as a child.

* What was the game?

* Who did you play it with?

* What did you like about the game?

And, do you still play this kind of game now?

PART 3

1 First of all, games children play.

Could you compare the kinds of games children in your country play outdoors, with those they play indoors?

What skills do children learn from playing games?

How does playing games develop a child’s imagination?

2 Now, let’s consider being competitive.

In what ways are people competitive at work in your country?

Do you think it is possible these days not to be competitive? Why?

LISTENING

Section 1: 1. Individual; 2. item; 3. equipment; 4. 700/seven hundred; 5. Reasonable costs; 6. airline; 7. B; 8. A; 9-10. CE (in either order). Section 2: 11. (leg) surgery; 12. 2½ / two-and-a-half hours; 13. to exert energy // exertion; 14. 36 / thirty-six kg/kilograms/kilogrammes; 15. leaning; 16. centre / center of gravity; 17. G; 18. I; 19. A; 20. D. Section 3: 21. (Physics) conferences; 22. A+/plus; 23. Arts (must end in ‘s’); 24. disorganised/disorganized; 25. A; 26. B; 27. C; 28. A; 29. C; 30. B. Section 4: 31. B; 32. E; 33. C; 34. F; 35. H; 36. debt; 37. edible // visually acceptable; 38. ¼ / quarter; 39. less; 40. A.

The highlighted text below is evidence for the answers above.

Narrator : Recording 15.

Practice Listening Test 3.

Section 1. Insurance.

You will hear a woman asking a sales assistant about insurance policies.

Read the example.

Sales Assistant : Good morning. Take a seat.

Assistant : I see you’ve picked up some of our brochures.

Customer : Yes. I’ve been reading the one on travel.

Sales Assistant : Would the travel insurance be for you, or for your family as well?

Narrator : The answer is ‘travel’.

On this occasion only, the first part of the conversation is played twice.

Before you listen again, you have 30 seconds to read questions 1 to 6.

Sales Assistant : Good morning. Take a seat.

I see you’ve picked up some of our brochures.

Customer : Yes. I’ve been reading the one on travel.

Sales Assistant : Would the travel insurance be for you, or for your family as well?

Customer : Just for me.

Sales Assistant : So, (1) Individual?

Customer : That’s right.

Sales Assistant : Are you looking for a basic or a comprehensive policy?

Customer : To be honest, I’ve had basic in the past, but it didn’t pay out very much.

Sales Assistant : That’s often true.

With our company, you can be insured for different amounts. For instance, in Section 1: Baggage and personal effects, you can be insured for all five subsections or for as few as two.

Customer : I think I’d like insurance for all five since I’m going to some unsafe places.

Sales Assistant : Wise decision.

Customer : By the way, can a camera be counted as a single (2) item, or must it be included in Cameras and portable electronic (3) equipment?

Sales Assistant : If you have an expensive camera, you can nominate it as a single (2) item. Our maximum payout is $1,500. Occasionally, people have their camera and computer stolen together. If insurance is only taken out on Subsection 2, this may not cover the replacement of both things.

Customer : That’s what happened with my previous policy.

However, in that one, there was a higher limit for lost or stolen money: yours is only (4)$700.

Sales Assistant : These days, with credit cards, people don’t carry much cash, so we’ve set the limit accordingly. Still, we pay out well for Documents.

Customer : Indeed.

In the Disrupted travel section, (5) ‘reasonable costs’ is written for a missed connection or an early return, instead of an amount of money. What exactly are (5) ‘reasonable costs’?

Sales Assistant : Put it this way: if you miss your flight due to poor weather that is verifiable, we pay $300 per day of lost time. If you arrive at check-in as the aircraft is leaving because you overslept, we still pay out, but only $100 a day. We rely on information from the (6) airline to determine this.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 7 to 10.

Sales Assistant : Are you also interested in vehicle insurance?

Customer : Yes, I am. I’m about to buy a nice (7) old car – a vintage Jaguar XJ6.

Sales Assistant : Hey, I used to have one of those although, nowadays, I prefer old motorbikes.

Did you know you can insure a vehicle on its own, or you can include it in our Multi-saver policy, along with your house and contents?

Customer : Yes, I saw that.

It’s true I’m buying an expensive car, (8) but I rent my house, so I’m not ready for Multi-saver.

Sales Assistant : I understand.

Have you decided which level of cover you’d like for your car?

Customer : Top cover.

Sales Assistant : Are you sure? It is pricey.

Customer : I know, but last time I had insurance, I wasn’t covered for storm damage.

Sales Assistant : Don’t tell me that was just before the November hailstorm!

Customer : Uh huh.

(9-10) So, I need storm damage insurance. Also, I’d like my policy to start as soon as I’ve paid for it. With my old one, there was a stand-down period of two weeks. Would you believe, I backed into a wall just three days after I’d taken out the policy.

Sales Assistant : Oh dear.

Customer : Then, I spent months fighting with the insurance company over the value of my car. I know it wasn’t worth much, but it was relatively new.

Sales Assistant : (9-10) If you choose Top Cover, we agree on a value for your car, and renegotiate each year to avoid disputes. Again, it’s not as cheap as some, but the policy works out better in the long run.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 1.

Narrator : Recording 16.

Section 2. Touring Devonport on a Segway.

You will hear a guide giving information on how to ride a Segway, and on places to see in Devonport.

Before you listen, you have 30 seconds to read questions 11 to 16.

Guide : Hi folks.

Before we start, I’d like to check if there’s anyone here under the age of thirteen. No? Anyone who’s pregnant, or who’s just had (11) leg surgery? Good. Our company isn’t insured for these users.

Now, I can see you’re all eyeing your Segways with interest. They’re curious beasts, aren’t they? Battery-driven two-wheeled vehicles often used in crowd control or postal delivery. I’ll be giving detailed operating instructions in a moment, and then I’ll outline our route.

In (12) 2½ hours, we won’t see everything in Devonport, but we’ll take in much more than if we were on foot. In fact, the maximum speed of a Segway is eighteen kilometres per hour.

Right-o. Safety gear. Here are your helmets. Please keep them on while riding. I hope you’re wearing flat enclosed shoes as well. Actually, you can operate a Segway in any footwear, but our company insists on sturdy shoes because we explore tunnels, and walk around rocks at North Head.

So. Riding a Segway is marvellously easy once you know how. It’s important not to think of a Segway as similar to a bicycle or a scooter since a Segway rider barely needs (13) to exert energy to move. This concept of movement with minimal (13) exertion seems foreign to some beginners, and most mishaps are the result of riders’ jerking backwards and losing their balance.

Another mistake learners make is to hop off a Segway when they’ve stopped, but a Segway is as steady when stationary as when in motion, so don’t dismount unless there’s a place you can’t ride into, like the tunnels in (17) North Head or (18) the French Café, where we end our tour.

A Segway is also robust. It’s quite light at (14) 36 kilograms, and its low centre of gravity and wide tyres mean it can handle many different surfaces. In fact, I’ve been in the snow with mine.

However, a Segway does have a delicate internal mechanism. It contains a gyroscope – a device that’s constantly moving to keep itself, and you, upright.

OK. Using the controls. The first thing you’ll notice is that there are hardly any. There’s an on-off button, and a screen indicating battery life and operational mode; we’ll be using ‘Normal’. So, let’s turn on our Segways. Now, hold the post upright, and place one foot on the platform. Push the on-off button. You’ll see the red lights rotating while the gyroscope is calibrating. When the lights turn green, release the kickstand, and place both feet on the platform. Now, lean forward slowly, and the machine will start; lean further forward, and it will speed up. In fact, (15) leaning is the way to control your Segway. (15) Leaning remember, not jerking – that’ll make you fall off. Lean backwards, and the Segway slows down; keep leaning backwards, and it stops. Twist the left handle to go left; twist the right to go right. Simple. With the internal gyroscope constantly monitoring your (16) centre of gravity, and adjusting the post accordingly, you’ll always keep your balance.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the talk, you have 30 seconds to read questions 17 to 20.

Guide : As I said earlier, we’re in this lovely harbour suburb of Devonport for (12) 2½ hours, beginning at the wharf and (18) ending up at the French Café. On the way, we’ll pass (19) a yacht club, quite a famous club in fact, and a church and graveyard that are the oldest in this part of the city. We’ll also climb two volcanoes. (20) The first volcano has remains from pre-European settlement in the form of storage pits and terraces, but there are no buildings left. (17) The second volcano, called North Head, has a museum at its base and some disused tunnels. The museum is devoted to naval history, but I’m afraid we won’t have time to visit. Where do we go next? Oh yes – (17) the rocks below North Head. The rocks below North Head lead to Cheltenham Beach. We’ll leave our Segways above the rocks while we explore. It’s too cold to swim at this time of year, but people do in summer.

Throughout our tour, I’ll be guiding you on your Segway adventure, and recounting some amazing tales of this historic suburb.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 2.

Narrator : Recording 17.

Section 3. Study options.

You will hear a professor talking to her student about his study options.

Before you listen, you have 30 seconds to read questions 21 to 24.

Proffesor Anderson : Come in, Rangi.

Rangi : Thank you, Professor Anderson.

Prof Anderson : I’ve been meaning to contact you, but I just got back last night.

Rangi : Where’ve you been?

Prof Anderson : (21) Conferences in Massachusetts and New York.

Rangi : For (21) Physics?

Prof Anderson : Yes.

Rangi : Great.

I’m looking forward to attending (21) conferences one day.

Prof Anderson : I imagine that won’t be so far away. I was extremely impressed with your Classical Mechanics exam. In fact, you were one of only two students out of 180 to get an (22) A+.

Rangi : Wow.

I really did enjoy the course.

Prof Anderson : So, how can I help you?

Rangi : I’m sorry to say it’s a bit of a long story. You see, I’ve had to rethink my studies completely, and I wonder if I’m making the right decision.

Prof Anderson : You’re doing two degrees, aren’t you – Science and (23) Arts?

Rangi : I was doing two. I’ve decided to focus on Science.

Prof Anderson : Oh?

Rangi : It all came about because I wanted to study abroad for a year. I was thinking about Edinburgh.

Firstly, I sought approval from the Maths and Physics Departments. I wanted to take Quantum Mechanics and Computer Simulations at Edinburgh.

Prof Anderson : Those are third-year courses, right?

Rangi : Yeah.

So, I received approval from Maths and Physics. The stumbling block was the higher authority – the Science Faculty. When I submitted my application, it was rejected.

Prof Anderson : What?

Rangi : It turns out that students who study abroad for a year can only do first- or second-year courses, or third-year courses in a subject that’s not their major.

Prof Anderson : I’ve never heard that before.

Rangi : Needless to say, the lecturers who approved my transfer hadn’t either, and nor does the regulation appear on the Science Faculty website.

Prof Anderson : That’d be right. This faculty is (24) disorganised.

Rangi : So, then I thought I’d take Arts courses at Edinburgh, and leave the third-year Maths until I came back. I quickly got approval for second-year History and Philosophy from the Arts Faculty.

Prof Anderson : When are you heading off?

Rangi : That’s just it. During this process I began to think carefully about my studies. To be honest, the Arts courses I’ve done were less challenging than the Science ones, so I’ve decided to drop (23) Arts.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 25 to 30.

Prof Anderson : Where do I figure in all this?

Rangi : The first week after I’d made my decision, I felt fine. (25) Without doing the Arts courses, I could finish my Science degree earlier. But this week, I’ve had some doubts.

When I started the two degrees, lecturers in the Science Faculty assured me that, these days, scientists need a rounded education, which they get if they take some Arts courses. I was even told I’d learn to write and think better if I did Philosophy.

Prof Anderson : (26) I do think the claims made by some lecturers are dubious.

Rangi : Then, there’s the fact that (27) now I’m going to be stuck here next year. I was so excited about going to Europe.

Prof Anderson : It is disappointing to give that up.

Still, the reason I wanted to contact you, Rangi, is that (28) I’m looking for students to work six hours a week in my lab. It’s paid work – not highly paid, but probably better than working in a bar. Also, we’ve just bought a new laser, which you’d learn to use.

Rangi : That sounds excellent.

Prof Anderson : As to going abroad, why not do your post-graduate studies in the US? There’s some amazing Physics being done in Massachusetts. If you like, I can send you the papers from the conference.

Rangi : Thanks.

Prof Anderson : Of course I’d be sad to lose you if you did go abroad, (29) but an (22) A+ student, like you, has a very good chance of winning a major scholarship.

Rangi : Goodness. I’ve never even considered that.

Prof Anderson : Personally, I think committing yourself to Science is the way to go.

Rangi : (30) Thanks, Professor Anderson. You’ve taken a load off my mind. Now, I don’t have to deal with Hegel or Leibnitz, I’ve plenty of time to read those conference papers.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 3.

Section 4. The ugly fruit movement.

You will hear a lecture on the ugly fruit movement as an effort to prevent food wastage.

Before you listen, you have 45 seconds to read questions 31 to 40.

Lecturer : Good Afternoon.

I was in such a hurry I didn’t have breakfast.

I’d like to show you these apples that my neighbour grew. This one’s fine, but this one’s an odd shape; you certainly wouldn’t find it on sale at a supermarket in this country. But, it tastes great.

Today, I’d like to discuss food wastage, and a movement attempting to address the issue. There are ugly-fruit exponents throughout Europe, but I’ll focus on a group in Portugal, called Fruta Feia, which means ‘ugly fruit’.

But first, some statistics. According to the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations, or the FAO, (31) around 40% of food for human consumption is wasted globally. The direct economic impact of this is a loss of $750 billion dollars each year. Meanwhile, every day, 870 million people worldwide go hungry. The environmental effects of food production are also astounding. (32) In the US, it’s estimated that the transportation of food uses ten percent of the total US energy budget. At the same time, (32) food production consumes 50% of our land and (32) 80% of our available fresh water. The single largest component of solid municipal waste – around 40% – is rotting food, and the gases that produces increase global warming.

Surprisingly, food wastage in developing countries is as high as in developed ones; what differs is where the wastage occurs. (33) In a country like Bolivia, Laos, or Zambia, food loss occurs after harvesting and during processing, due to inadequate storage, poor transportation infrastructure, and warm climatic conditions, whereas in the developed world, wastage occurs at the retail and consumer level – consumers seldom plan their shopping, which leads to over-purchasing; or, the enormous variety of supermarket food encourages impulse buying. Furthermore, consumers are strongly advised by regulatory authorities to dispose of food that may well be edible but which has passed its use-by date. (34) This overly-cautious labelling with use-by dates is something Fruta Feia has campaigned against.

(35) The complex food rules of the European Union began in 1992, and have fuelled great discontent, especially in the UK, where journalists famously lampooned bureaucrats for banning bent bananas and curved cucumbers.

After such criticism, the EU did reduce its list of rules for selling fruit and vegetables from 36 to ten. The difficulty lies with retailers that reject large amounts of food due to aesthetic considerations, believing spinach has to be completely green, and tomatoes perfectly spherical. Any blemish, even one that doesn’t affect the edible contents, signals an item’s destruction.

To reduce wastage, the FAO recommends three things. Priority should be given to preventing wastage in the first place to by balancing production with demand. Where there is surplus, re-use by donation to needy people or to farm animals should take place. Lastly, if re-use is impossible, recycling and recovery should be pursued.

Back to Portugal and Fruta Feia. Portugal, in Western Europe, is a developed nation of 10.5 million people. It joined the EU 30 years ago. In 2011, however, it was severely affected by a (36) debt crisis, and its economy is still shaky. As a result of the (36) debt crisis, unemployment is high, and hundreds of thousands of people have left the country. In these hard times, many Portuguese are hunting for bargains. So, enter the co-operative Fruta Feia, set up in Lisbon in 2013 by Isabel Soares.

Fruta Feia has three aims: to feed people cheaply; to encourage EU rule-makers to overhaul use-by dates; and, to subvert notions of both what is (37) visually acceptable and what is (37) edible. When surveyed, most people who join Fruta Feia also support local agriculture.

Isabel Soares estimates that one-third of Portugal’s farm produce is thrown out due to artificial standards set by supermarkets. A farmer, José Dias, who supplies Fruta Feia, said that from his annual production of tomatoes, one (38) quarter did not meet supermarket standards, so were dumped. Now, Fruta Feia buys his ‘reject’ tomatoes at half the price he would sell them to a supermarket. Consequently, Fruta Feia’s members also pay (39) less for tomatoes than supermarket shoppers do.

As to the myriad of regulations set by the EU, Fruta Feia does not contravene any: its own produce is unlabelled and unpackaged. Despite this somewhat unglamorous look, it has sold more than 20 metric tons of food in Lisbon alone.

(40) Personally, even while the contribution of Fruta Feia and its 1,000 members is tiny, they are still, literally and metaphorically, eating away at the mountains of food that otherwise go to waste. And I salute that.

Narrator: That is the end of the Listening test.

You now have ten minutes to transfer your answers to your answer sheet.

READING: Passage 1: 1. B; 2. C; 3. B; 4. A; 5. D; 6. E; 7. C; 8. K; 9. E; 10. I; 11. D; 12. F; 13. C. Passage 2: 14. D; 15. D; 16. C; 17. A; 18. B; 19. C; 20. volatility; 21. cortisol; 22. Forward; 23. wild; 24. Further; 25. N/No; 26. NG/Not Given; 27. Y/Yes. Passage 3: 28. A; 29. D; 30. A; 31. B; 32. C; 33. B; 34. autonomous; 35. non-human persons; 36. habeas corpus; 37. protection; 38. all; 39. succeeded; 40. perceptions.

The highlighted text below is evidence for the answers above.

If there is a question where ‘Not given’ is the answer, no evidence can be found, so there is no highlighted text.

Márquez and Magical Realism

A (4) When Gabriel García Márquez died in 2014, he was mourned around the world, as readers recalled his 1967 novel, One hundred years of solitude, which has sold more than 25 million copies, and led to Márquez’s receipt of the 1982 Nobel Prize for Literature.

B (1) Born in 1927, in a small town on Colombia’s Caribbean coast called Aracataca, Márquez was immersed in Spanish, black, and indigenous cultures. (3) In such remote places, religion, myth, and superstition hold sway over logic and reason, or perhaps operate as parallel belief systems. Certainly, the ghost stories told by his grandmother affected the young Gabriel profoundly, and a pivotal character in his 1967 epic is indeed a ghost.

(1) Márquez’s family was not wealthy: there were twelve children, and his father worked as a postal clerk, a telegraph operator, and an occasional pharmacist. Márquez spent much of his childhood in the care of his grandparents, (3) which may account for the main character in One hundred years of solitude resembling his maternal grandfather. Although Márquez left Aracataca aged eight, the town and its inhabitants never seemed to leave him, and suffuse his fiction.

C One hundred years of solitude was the fourth of fifteen novels, (7) but Márquez was an equally passionate and prolific journalist.

In Bogotá, during his twenties and thirties, Márquez experienced La Violencia, a period of great political and social upheaval, when around 300,000 Colombians were killed. Certainly, life was never safe for journalists, and after writing an article on corruption in the Colombian navy in 1955, Márquez was forced to flee to Europe. (2) Incidentally, in Paris, he discovered that European culture was not richer than his own, and he was disappointed by Europeans who were patronising towards Latin Americans. On return to the southern hemisphere, Márquez wrote for Venezuelan newspapers and the Cuban press agency.

D In terms of politics, Márquez was leftwing. In Chile, he campaigned against the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet; in Venezuela, he financed a political party; and, in Nicaragua, he defended revolutionaries. (5) He considered Fidel Castro, the President of Cuba, as a dear friend. Since the US was hostile towards Castro’s communist regime, which Márquez supported, the writer was banned from visiting the US until invited by President Clinton in 1995. The novels of Márquez are imbued with his politics, but this does not prevent readers from enjoying a good yarn.

E Márquez maintained that in Latin America so much that is real would seem fantastic elsewhere, while so much that is magical seems real. He was an exponent of a genre known as Magical Realism.

‘If you can explain it,’ said the Mexican critic, Luis Leal, ‘then it’s not Magical Realism.’ This demonstrates the difficulty of determining what the genre encompasses and which writers belong to it.

The term Magical Realism is usually applied to literature, but its first use was probably in (8) 1925, when a German art critic reviewed paintings similar to those of Surrealism.

(6) Many critics define Magical Realism by what it is not. Realism describes lives that could be real; Magical Realism uses the detail and the tone of a realist work, but includes the magical as though it were real. The ghosts in One hundred years of solitude and in the American Toni Morrison’s Beloved are presented by their narrators as normal, (11) so readers accept them unhesitatingly. Likewise, a character can live for 200 years in a Magical Realist novel. Surrealism explores dream states and psychological experiences; Magical Realism does not. Science Fiction describes a new or an imagined world, as in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, but Magical Realism depicts the real world. Nor is Magical Realism (9) fantasy, like Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, in which an ordinary man awakens to find he has transformed into a cockroach. This is because the writer and the reader of that story cannot decide whether to ascribe natural or (10) supernatural causes to the event. In contrast, in a work by Márquez, the world is both natural and (10) supernatural, both rational and irrational, and this binary nature fascinates readers.

Magical Realism does share some common ground with post-modernism since the acts of writing and reading are self-reflexive. A narrative may (12) not be linear, but may double back on itself, or be discontinuous, and the notion of character is more illusive than in other genres.

Naturally, some of these elements disturb a reader although the enormous success of One hundred years of solitude and the hundreds of (13) other Magical Realist works from authors as far apart as Norway, Nigeria, and New Zealand would seem to belie it.

F Latin America has had a long history of conquest, revolution, and dictatorship; of hunger, poverty, and chaos, yet, at the same time, is endowed with rich cultures, with warm, emotional people, many of whom, like Márquez, remain optimistically utopian. Gabriel García Márquez has passed away, but his fiction will certainly endure.

Recent stock-market crashes

For as long as there have been financial markets, there have been financial crises. (14) Most economists agree, however, that from 1994 to 2013 crashes were deeper and the resultant troughs longer-lasting than in the 20-year period leading up to 1994. Two notable crashes, the Nifty Fifty in the mid-1970s and Black Monday in 1987, had an average loss of about 40% of the value of global stocks, and recovery took 240 days each, whereas the Dot-com and credit crises, post-1994, had an average loss of about 52%, and endured for 430 days. What economists do not agree upon is why recent crises have been so severe or how to prevent their recurrence.

John Coates, from the University of Cambridge in the UK and a former trader for Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank, believes three separate but related phenomena explain the severity. The first is dangerous but predictable risk-taking on the part of traders. The second is a lack of any risk-taking when markets become too volatile. (15) (Coates does not advocate risk-aversion since risk-taking may jumpstart a depressed market.) The last is a new policy of transparency by the US Federal Reserve – known as the Fed – that may have encouraged stock-exchange complacency, compounding the dangerous risk-taking.

Many people imagine a trader to have a great head for maths and a stomach for the rollercoaster ride of the market, but Coates downplays arithmetic skills, and doubts traders are made of such stern stuff. Instead, he draws attention to the physiological nature of their decisions. Admittedly, there are women in the industry, but traders are overwhelmingly male, and testosterone appears to affect their choices.

(16) Another common view is that traders are greedy as well as thrill-seeking. Coates has not researched financial incentive, (17) but blood samples taken from London traders who engaged in simulated risk-taking exercises for him in 2013 confirmed the prevalence of testosterone, cortisol, and dopamine – a neurotransmitter precursor to adrenalin associated with raised blood pressure and sudden pleasure.

Certainly anyone faced with danger has a stress response involving the body’s preparation for impending movement – for what is sometimes called ‘Fight or flight’, but, as Coates notes, any physical act at all produces a stress response: even a reader’s eye movement along words in this line requires cortisol and adrenalin. (18) Neuroscientists now see the brain not as a computer that acts neutrally, involved in a process of pure thought, but as a mechanism to plan and carry out movement, since every single piece of information humans absorb has an attendant pattern of physical arousal.

For muscles to work, fuel is needed, so cortisol and adrenalin employ glucose from other muscles and the liver. To burn the fuel, oxygen is required, so slightly deeper or faster breathing occurs. To deliver fuel and oxygen to the body, the heart pumps a little harder and blood pressure rises. Thus, the stress response is a normal part of life, as well as a resource in fighting or fleeing. Indeed, it is a highly pleasurable experience in watching an action movie, making love, or pulling off a multi-million-dollar stock-market deal.

Cortisol production also increases during exposure to uncertainty. For example, people who live next to a train line adjust to the noise of passing trains, but visitors to their home are disturbed. The phenomenon is equally well-known of anticipation being worse than an event itself: sitting in the waiting room thinking about a procedure may be more distressing than occupying the dentist’s chair and having one. (19) Interestingly, if a patient does not know approximately when he or she will be called for that procedure, cortisol levels are the most elevated of all. This appeared to happen with the London traders participating in some of Coates’ gambling scenarios.

When there is too much (20) volatility in the stock market, Coates suspects adrenaline levels decrease while (21) cortisol levels increase, explaining why traders take fewer risks at that time. In fact, typically traders freeze, becoming almost incapable of buying or selling anything but the safest bonds. In Coates’ opinion, the market needs investment as it falls and at rock bottom – at such times, greed is good.

The third matter – the behaviour of the Fed – Coates thinks could be controlled, albeit counter-intuitively. Since 1994, the US Federal Reserve has adopted a policy called (22) Forward Guidance. Under this, the public is informed at regular intervals of the Fed’s plans for short-term interest rates. Recently, rates have been raised by small but predictable increments. By contrast, in the past, the machinations of the Fed were largely secret, and its interest rates fluctuated apparently randomly. Coates hypothesises this meant traders were on guard and less likely to indulge in (23) wild speculation. In introducing (22) Forward Guidance the Fed hoped to lower stock and housing prices; instead, before the crash of 2008, the market surged from (24) further risk-taking, like an unleashed pit bull terrier.

(25) There are many economists who disagree with Coates, but he has provided some physiological evidence for both traders’ recklessness and immobilisation, and made the radical proposal of greater opacity at the Fed. (27) Although, as others have noted, we could just let more women onto the floor.

Animal personhood

(28) Aristotle, a 4th-century-BC Greek philosopher, created the Great Chain of Being, in which animals, lacking reason, ranked below humans. The Frenchman, René Descartes, in the 17th century AD, considered animals as more complex creatures; however, without souls, they were merely automatons. One hundred years later, the German, (29) Immanuel Kant, proposed animals be treated less cruelly, which might seem an improvement, but Kant believed this principally because he thought acts of cruelty affect their human perpetrators detrimentally. The mid-19th century saw the Englishman, (30) Jeremy Bentham, questioning not their rationality or spirituality, but whether animals could suffer irrespective of the damage done to their victimisers; he concluded they could; and, (31) in 1824, the first large organisation for animal welfare, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, was founded in England. In 1977, the Australian, Peter Singer, wrote the highly influential book Animal liberation, in which he debated the ethics of meat-eating and factory farming, and raised awareness about inhumane captivity and experimentation. (32) Singer’s title deliberately evoked other liberation movements, like those for women, which had developed in the post-war period.

More recently, an interest in the cognitive abilities of animals has resurfaced. It has been known since the 1960s that (33) chimpanzees have sophisticated tool use and social interactions, but research from the last two decades has revealed they are also capable of empathy and grief, and they possess self-awareness and self-determination. Other primates, dolphins, whales, elephants, and African grey parrots are highly intelligent too. It would seem that with each new proof of animals’ abilities, questions are being posed as to whether creatures so similar to humans should endure the physical pain or psychological trauma associated with habitat loss, captivity, or experimentation. While there may be more laws protecting animals than 30 years ago, in the eyes of the law, no matter how smart or sentient an animal may be, it still has a lesser status than a human being.

Steven Wise, an American legal academic, has been campaigning to change this. He believes animals, like those listed above, are (34) autonomous – they can control their actions, or rather, their actions are not caused purely by reflex or from innateness. He wants these animals categorized legally as (35) non-human persons because he believes existing animal-protection laws are weak and poorly enforced. He famously quipped that an aquarium may be fined for cruel treatment of its dolphins but, currently, the dolphins can’t sue the aquarium.

While teaching at Vermont Law School in the 1990s, Wise presented his students with a dilemma: should an anencephalic baby be treated as a legal person? (Anencephaly is a condition where a person is born with a partial brain and can breathe and digest, due to reflex, but otherwise is barely alert, and not autonomous.) Overwhelmingly, Wise’s students would say ‘Yes’. He posed another question: could the same baby be killed and eaten by humans? Overwhelmingly, his students said ‘No’. His third question, always harder to answer, was: why is an anencephalic baby legally a person yet not so a fully-functioning bonobo chimp?

Wise draws another analogy: between captive animals and slaves. Under slavery in England, a human was a chattel, and if a slave were stolen or injured, the thief or violator could be convicted of a crime, and compensation paid to the slave’s owner though not to the slave. It was only in 1772 that the chief justice of the King’s Bench, Lord Mansfield, ruled that a slave could apply for habeas corpus, Latin for: ‘You must have the body’, as free men and women had done since ancient times. Habeas corpus does not establish innocence or guilt; rather, it means a detainee can be represented in court by a proxy. Once slaves had been granted habeas corpus, they existed as more than chattels within the legal system although it was another 61 years before slavery was abolished in England. Aside from slaves, Wise has studied numerous cases in which a writ of (36) habeas corpus had been filed on behalf of those unable to appear in court, like children, patients, prisoners, or the severely intellectually impaired. In addition, Wise notes there are entities that are not living people that have legally become non-human persons, including: ships, corporations, partnerships, states, a Sikh holy book, some Hindu idols and the Wanganui River in New Zealand.

In conjunction with an organisation called the Non-human Rights Project (NhRP), Wise has been representing captive animals in US courts in an effort to have their legal status reassigned. Thereafter, the NhRP plans to apply, under habeas corpus, to represent the animals in other cases. Wise and the NhRP believe a new status will discourage animal owners or nation states from neglect or abuse, which current laws fail to do.

Richard Epstein, a professor of Law at New York University, is a critic of Wise’s. His concern is that if animals are treated as independent holders of rights there would be little left of human society, in particular, in the food and agricultural industries. Epstein agrees some current legislation concerning animal (37) protection may need overhauling, but he sees no underlying problem.

Other detractors say that the push for personhood misses the point: it focuses on animals that are similar to humans without addressing the fundamental issue that (38) all species have an equal right to exist. Thomas Berry, of the Gaia Foundation, declares that rights do not emanate from humans but from the universe itself, and, as such, all species have the right to existence, habitat, and role (be that predator, plant, or decomposer). Dramatically changing human behaviour towards other species is necessary for their survival – and that doesn’t mean declaring animals as non-human persons.

To date, the NhRP has not (39) succeeded in its applications to have the legal status of chimpanzees in New York State changed, but the NhRP considers it some kind of victory that the cases have been heard. Now, the NhRP can proceed to the Court of Appeals, where many emotive cases are decided, and where much common law is formulated.

Despite setbacks, Wise doggedly continues to expose brutality towards animals. Thousands of years of (40) perceptions may have to be changed in this process. He may have lost the battle, but he doesn’t believe he’s lost the war.

WRITING: Task 1

The diagram shows the 15-month process of French blue mussel production from spawning to sale.

After spawning and fecondation, mussel larvae spend three to four weeks in the trochophore stage, at which time they are around 0.3 millimetres in length. During the veliger larval stage that follows (2-9 days), they double in size. Metamorphosis occurs at around three months, when the creatures grow shells and settle either on-bottom or off-bottom.

On-bottom mussels attach themselves to rocks on the seabed as in nature.

Off-bottom mussels live on artificial structures: intertidal racks with coconut fibre ropes, or suspended subtidal cages. After six weeks, these 3-10-millimetre mussels are manually transferred to bouchot ropes or longlines, where most of their growth takes place.

The bouchot culture method is intertidal. Mussel-covered ropes spiral around poles fixed in rows to the seabed. Annual yield is 17.5 tonnes. The longline method is subtidal, with clusters of mussels hanging from buoyant ropes just below the surface of the sea. Annual yield is around 20 tonnes.

Mussel harvesting is mechanical.

On shore, mussels are separated, and processed for sale. The average length of a marketable French blue mussel is 50 millimetres. (194 words)

Although plagiarism is stealing other people’s ideas, thoughts and words, and considered unacceptable by most, it is becoming more and more a fact of life. As the world population increases, and millions are using the Worldwide Web to search for information and to communicate in general, it becomes much harder to police what is on the Web itself. Checking the originality of the vast amount of material that is written on the Web is difficult; deciding whether a student’s essay or a journalist’s article is original and praiseworthy, can be equally difficult.

Authors, journalists, students and researchers are all still supposed to offer original work, and provide their sources if they use someone else’s ideas. But some do not do either. Simply by going online, a writer can copy and paste from various websites and blogs, and change a word here, a word there, without being detected. Whether a writer’s work is original or not can often be difficult to ascertain. Today, citing books and journal articles often comes second to using the information on the Web.

However, not all is lost for those people who consider plagiarists to be cheats. There are now online plagiarism checkers that are used by teachers, students and others. Essays can be transferred to the chosen site and checked for originality. Not only can writers’ words be scrutinised, but their sources can also be checked for possible uncited borrowings. Self-checking one’s own writings undoubtedly provides relief.

Nevertheless, there is nothing new about plagiarism. For example, if William Shakespeare had not used the Holinshed Chronicles as the basis for his history plays, and a work such as Macbeth, English literature would be poorer. Yet although Shakespeare uses the plots for his plays, the language, thoughts, and characterisations are very much his.

Today, the main problem with plagiarism is that some writers cheat their way to success without offering originality. However, even though there are ways of checking for plagiarism, it is understandable why some do not see plagiarism as a problem since our technological world is putting everything out there for all to do what they like with, thus making it more and more impossible to police.

Despite the power of the Worldwide Web, I believe that writers should avoid cheating, and instead, rigorously uphold the conventions of good writing. They must acknowledge their sources, avoid plagiarising others, and show some originality. (397 words)

*Plagiarism is copying another person’s work, without acknowledgment, and pretending it is one’s own.