Firstly, tear out the Test 4 Listening / Reading Answer Sheet at the back of this book.

The Listening test lasts for about 20 minutes.

Write your answers on the pages below as you listen. After Section 4 has finished, you have ten minutes to transfer your answers to your Listening Answer Sheet. You will need to time yourself for this transfer.

After checking your answers on pp 162-167, go to page 9 for the raw-score conversion table.

PLAY RECORDING #19.

PLAY RECORDING #19.

SECTION 1 Questions 1-10

CHILDREN’S DAY CARE

Questions 1-3

Answer the questions below.

Write ONE WORD OR A NUMBER for each answer.

Example What are Angela and Sanjit going to drink before Tom arrives?

Coffee

1 What is Sanjit’s son called?

………………..………………..

2 What is the meaning of the name Zoe?

………………..………………..

3 What is the maximum daily rate in dollars at Zoe’s day care?

………………..………………..

Choose TWO letters, A-E.

Which TWO of the following happen at Zoe’s day care?

A Parents must provide diapers and food for their children.

B Children’s birthdays are celebrated with songs and games.

C Children are divided by age into rooms named after animals.

D Parents who collect their children fifteen minutes late are fined.

E The centre reserves the right to send home children who are ill.

Complete the table below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS for each answer.

PLAY RECORDING #20.

PLAY RECORDING #20.

SECTION 2 Questions 11-20

A VERY SMALL HOUSE

Questions 11-15

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

11 What size is Charlotte’s house?

A 8 square metres

B 80 square metres

C 800 square metres

12 In the past, what did people think about Charlotte’s lifestyle?

A They were curious.

B They were hostile.

C They were uninterested.

13 What does Charlotte’s story about smoking show?

A Her mother is a keen supporter.

B Attitudes and behaviours do change.

C Americans approve of a ban on smoking in public.

14 How have American family and house sizes changed from 1945 to the present?

A Families and houses have shrunk.

B Families and houses have grown.

C Families have shrunk; houses have grown.

15 Who inspired Charlotte to live in a very small house?

A Her mother in France

B Her neighbours in Vietnam

C Her partner in Chicago

Questions 16-20

Complete the sentences below.

Write NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS OR A NUMBER for each answer.

16 Since living in Mozambique, Charlotte has not used a fridge or a..……………. .

17 Charlotte believes children who live in small houses tend to………………. more.

18 Now, every item Charlotte owns must be both………………. .

19 Charlotte used to have 4,000 possessions; she now has………………. .

20 Charlotte thinks the greatest saving from her lifestyle is she now has more………………. .

PLAY RECORDING #21.

PLAY RECORDING #21.

SECTION 3 Questions 21-30

A BUSINESS ASSIGNMENT

Questions 21-26

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

21 How many words has Luca written of his short essay so far?

A 450

B 560

C 800

22 A business plan often includes information about a company’s

A past performance and potential problems.

B present situation and its growth forecast.

C current state and a three-year sales projection.

23 According to Luca, a business plan might be written for

A future investors.

B tax authorities.

C a company’s CEO.

24 What do the students think about design controls to measure the success of a business?

A They think controls are desirable.

B They think controls are essential.

C They are not sure what controls are.

25 A company usually makes separate

A Marketing and Production Plans.

B Finance and Purchasing Plans.

C plans for each section of a master plan.

26 How does Luca feel about detailed business plans?

A Surprised

B Inspired

C Uninterested

Complete the information below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS for each answer.

Business Profile in detail:

• Business Name

• Location

• Ownership (29)………………..

• Business Activity

• Market Entry Strategy

• Future Objectives

• Legal (30)………………..

PLAY RECORDING #22.

PLAY RECORDING #22.

SECTION 4 Questions 31-40

THE BENEFITS OF LITERATURE

Questions 31-34

Complete the sentences below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS for each answer.

31 The speaker, Kidd, and Castano believe………………..is the most useful kind to read for cognitive and emotional intelligence.

32 Theory of Mind is a person’s capacity to understand that other people’s mental states may be………………..from their own.

33 Austen, Fitzgerald, and al Aswany are examples of………………..literary authors.

34 A major disadvantage of popular literature is that it leaves a reader’s worldview……………. .

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

35 Kidd and Castano’s experimental volunteers read from

A fiction and non-fiction.

B texts of their own choice.

C different genres or nothing at all.

36 According to the speaker, …… may benefit from a literature-focused approach.

A prisoners

B delinquents

C illiterate adults

37 The speaker compares reading the Harry Potter series to watching TV for the same amount of time to imply that

A they are both entertaining and educational.

B watching TV causes more neural activity.

C reading creates deeper emotional attachment.

38 According to the Common Sense Media report, how many teens read for pleasure daily in 1984 and 2014?

A 17% and 9%

B 31% and 27%

C 31% and 17%

39 Why did the teenagers in the Common Sense report say they read less?

A They didn’t enjoy reading.

B They lacked reading skills.

C They didn’t have time.

40 The speaker gave her neighbour a copy of The Little Prince because

A reading literature helps people cope with a complex world.

B this French classic is one of her personal favourites.

C she believes literary fiction is neglected.

Firstly, turn over the Test 4 Listening Answer Sheet you used earlier to write your Reading answers on the back.

The Reading test lasts exactly 60 minutes.

Certainly, make any marks on the pages below, but transfer your answers to the answer sheet as you read since there is no extra time at the end to do so.

After checking your answers on pp 167-169, go to page 9 for the raw-score conversion table.

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-14, based on Passage 1 below.

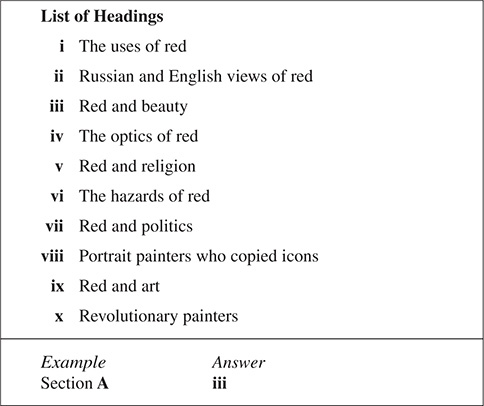

Questions 1-6

Reading Passage 1 on the following page has seven sections: A-G.

Choose the correct heading for sections B-G from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number, i-x, in boxes 1-6 on your answer sheet.

1 Section B

2 Section C

3 Section D

4 Section E

5 Section F

6 Section G

A In Old Slavonic, a language that precedes Russian, ‘red’ has a similar root to the words ‘good’ and ‘beautiful’. Indeed, until the 20th century, Krasnaya Ploshchad, or Red Square, in central Moscow, was understood by locals as ‘Beautiful Square’. For Russians, red has great symbolic meaning, being associated with goodness, beauty, warmth, vitality, jubilation, faith, love, salvation, and power.

B Because red is a long-wave colour at the end of the spectrum, its effect on a viewer is striking: it appears closer than colours with shorter waves, like green, and it also intensifies colours placed alongside it, which accounts for the popularity of red and green combinations in Russian painting.

C Russians love red. In the applied arts, it predominates: bowls, boxes, trays, wooden spoons, and distaffs for spinning all feature red, as do children’s toys, decorative figurines, Easter eggs, embroidered cloths, and garments. In the fine arts, red, white, and gold form the basis of much icon painting.

D In pre-Christian times, red symbolised blood. Christianity adopted the same symbolism; red represented Christ or saints in their purification or martyrdom. The colour green, meantime, signified wisdom, while white showed a person reborn as a Christian. Thus, in a famous 15th-century icon from the city of Novgorod, Saint George and the Dragon, red-dressed George sports a green cape, and rides a pure-white stallion. In many icons, Christ and the angels appear in a blaze of red, and the mother of Christ can be identified by her long red veil. In an often-reproduced icon from Yaroslavl, the Archangel Michael wears a brilliant red cloak. However, the fires of Hell that burn sinners are also red, like those in an icon from Pskov.

E A red background for major figures in icons became the norm in representations of mortal beings, partly to add vibrancy to skin tones, and one fine example of this is a portrait of Nikolai Gogol, the writer, from the early 1840s. When wealthy aristocrats wished to be remembered for posterity, they were often depicted in dashing red velvet coats, emulating the cloaks of saints, as in the portraits of Jakob Turgenev in 1696, or of Admiral Ivan Talyzin in the mid-1760s. Portraits of women in Russian art are rare, but the Princess Yekaterina Golitsyna, painted in the early 1800s, wears a fabulous red shawl.

Common people do not appear frequently in Russian fine art until the 19th century, when their peasant costumes are often white with red embroidery, and their elaborate headdresses and scarves are red. The women in the 1915 painting, Visiting, by Abram Arkhipov seem aflame with life: their dresses are red; their cheeks are red; and, a jug of vermillion lingonberry cordial glows on the table beside them.

Russian avant-garde painters of the early 20th century are famous beyond Russia as some of the greatest abstract artists. Principal among these are Nathan Altman, Natalia Goncharova, Wassily Kandinsky, and Kazimir Malevich, who painted the ground-breaking White on white as well as Red Square, which is all the more compelling because it isn’t quite square. Malevich used primary colours, with red prominent, in much of his mature work. Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin is hailed as a genius at home, but less well-known abroad; his style is often surreal, and his palette is restricted to the many hues of red, contrasting with green or blue. The head in his 1915 Head of a youth is entirely red, while his 1925 painting, Fantasy, shows a man in blue, on a larger-than-life all-red horse, with a blue town in blue mountains behind.

F Part of the enthusiasm for red in the early 20th century was due to the rise of the political movement, communism. Red had first been used as a symbol of revolution in France in the late 18th century. The Russian army from 1918-45 called itself the Red Army to continue this revolutionary tradition, and the flag of the Soviet Union was the Red Flag.

Soviet poster artists and book illustrators also used swathes of red. Some Social Realist painters have been discredited for their political associations, but their art was potent, and a viewer cannot help but be moved by Nikolai Rutkovsky’s 1934 Stalin at Kirov’s coffin. Likewise, Alexander Gerasimov’s 1942 Hymn to October or Dmitry Zhilinsky’s 1965 Gymnasts of the USSR stand on their own as memorable paintings, both of which include plenty of red.

G In English, red has many negative connotations – red for debt, a red card for football fouls, or a red-light district – but in Russian, red is beautiful, vivacious, spiritual, and revolutionary. And Russian art contains countless examples of its power.

Complete the table below.

Choose ONE WORD OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 7-12 on your answer sheet.

Choose TWO letters: A-E.

Write the correct letters in box 13 on your answer sheet.

The list below includes associations Russians make with the colour red.

Which TWO are mentioned by the writer of the passage?

A danger

B wealth

C intelligence

D faith

E energy

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-27, based on Passage 2 below.

Lepidoptera

Myths and Misnomers

A buttercup is a small, bright yellow flower; a butternut is a yellow-fleshed squash; and, there is also a butter bean. The origin of the word ‘butterfly’ may be similar to these plants – a creature with wings the colour of butter – but a more fanciful notion is that ‘flutterby’ was misspelt by an early English scribe since a butterfly’s method of flight is to flutter by. Etymologists may not concur, but entomologists agree with each other that butterflies belong to the order of Lepidoptera, which includes moths, and that ‘lepidoptera’ accurately describes the insects since ‘lepis’ means ‘scale’ and ‘pteron’ means ‘wing’ in Greek.

Until recently, butterflies were prized for their evanescence – people believed that adults lived for a single day; it is now known this is untrue, and some, like monarch butterflies, live for up to nine months.

Butterflies versus Moths

Butterflies and moths have some similarities: as adults, both have four membranous wings covered in minute scales, attached to a short thorax and a longer abdomen with three pairs of legs. They have moderately large heads, long antennae, and compound eyes; tiny palps for smell; and, a curling proboscis for sucking nectar. Otherwise their size, colouration, and lifecycles are the same.

Fewer than one percent of all insects are butterflies, but they hold a special place in the popular imagination as being beautiful and benign. Views of moths, however, are less kind since some live indoors and feast on cloth; others damage crops; and, most commit suicide, being nocturnal and drawn to artificial light. There are other differences between butterflies and moths; for example, when resting, the former fold their wings vertically above their bodies, while the latter lay theirs flat. Significantly, butterfly antennae thicken slightly towards their tips, whereas moth antennae end in something that looks like a V-shaped TV aerial.

The Monarch Butterfly

Originating in North America, the black-orange-and-white monarch butterfly lives as far away as Australia and New Zealand, and for many children it represents a lesson in metamorphosis, which can even be viewed in one’s living room if a pupa is brought indoors.

It is easy to identify the four stages of a monarch’s lifecycle – egg, larva, pupa, and adult – but there are really seven. This is because, unlike vertebrates, insects do not have an internal skeleton, but a tough outer covering called an exoskeleton. This is often shell-like and sometimes indigestible by predators. Muscles are hinged to its inside. As the insect grows, however, the constraining exoskeleton must be moulted, and a monarch butterfly undergoes seven moults, including four as a larva.

Temperature dramatically affects butterfly growth: in warm weather, a monarch may go through its seven moults in just over a month. Time spent inside the egg, for instance, may last three to four days in 25° Celsius, but in 18°, the whole process may take closer to eight weeks, with time inside the egg eight to twelve days. Naturally, longer development means lower populations due to increased predation.

A reliable food supply influences survival, and the female monarch butterfly is able to sniff out one particular plant its young can feed off – milkweed or swan plant. There are a few other plants larvae can eat, but they will resort to these only if the milkweed is exhausted and alternatives are very close by. Moreover, a female butterfly may be conscious of the size of the milkweed on which she lays her eggs since she spaces them, but another butterfly may deposit on the same plant, lessening everyone’s chance of survival.

While many other butterflies are close to extinction due to pollution or dwindling habitat, the global numbers of monarchs have decreased in the past two decades, but less dramatically.

Monarch larvae absorb toxins from milkweed that render them poisonous to most avian predators who attack them. Insect predators, like aphids, flies, and wasps, seem unaffected by the poison, and are therefore common. A recent disturbing occurrence is the death of monarch eggs and larvae from bacterial infection.

Another reason for population decline is reduced wintering conditions. Like many birds, monarch butterflies migrate to warmer climates in winter, often flying extremely long distances, for example, from Canada to southern California or northern Mexico, or from southern Australia to the tropical north. They also spend some time in semi-hibernation in dense colonies deep in forests. In isolated New Zealand, monarchs do not migrate, instead finding particular trees on which to congregate. In some parts of California, wintering sites are protected, but in Mexico, much of the forest is being logged, and the insects are in grave danger.

Milkweed is native to southern Africa and North America, but it is easy to grow in suburban gardens. Its swan-shaped seedpods contain fluffy seeds used in the 19th century to stuff mattresses, pillows, and lifejackets. After milkweed had hitched a lift on sailing ships around the Pacific, the American butterflies followed with Hawaii seeing their permanent arrival in 1840, Samoa in 1867, Australia in 1870, and New Zealand in 1873. As butterfly numbers decline sharply in the Americas, it may be these Pacific outposts that save the monarch.

Questions 14-17

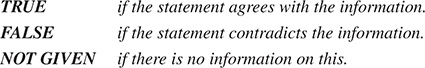

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2?

In boxes 14-17 on your answer sheet, write:

14 One theory is that the word ‘butterfly’ means an insect the colour of butter.

15 Another theory is that a ‘butterfly’ was a mistake for a ‘flutterby’.

16 The Greeks had a special reverence for butterflies.

17 The relative longevity of butterflies has been understood for some time.

Questions 18-21

Classify the things on the following page that relate to:

A butterflies only.

B moths only.

C both butterflies and moths.

Write the correct letter, A, B, or C, in boxes 18-21 on your answer sheet.

18 They have complex eyes.

19 Humans view them negatively.

20 They fold their wings upright.

21 They have more pronounced antennae.

Complete the summary below using the numbers or words, A-I, below.

Write the correct letter, A-I, in boxes 22-27 on your answer sheet.

The Monarch Butterfly

Monarch butterflies can live for up to nine months. Indigenous to (22)……………….., they are now found throughout the Pacific as well.

Since all insects have brittle exoskeletons, they must shed these regularly while growing. In the life of a monarch butterfly, there are (23)……………….. moults.

Several factors affect butterfly populations. Low temperatures mean animals take longer to develop, increasing the risk of predation. A steady supply of a specific plant called (24)……………….. is necessary; and a small number of eggs laid per plant. Birds do attack monarch butterflies, but as larvae and adults contain toxins, such attacks are infrequent. Insects, unaffected by poison, and (25)……………….. pose a greater threat.

The gravest danger to monarch butterflies is the reduction of their wintering grounds, by deforestation, especially in (26)……………….. .

Monarchs do not migrate long distances within New Zealand, but they gather in large colonies on certain trees. It is possible that the isolation of this country and some other islands in (27)……………….. will save monarchs.

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 28-40, based on Passage 3 below.

HOW FAIR IS FAIR TRADE?

The fair-trade movement began in Europe in earnest in the post-war period, but only in the last 25 years has it grown to include producers and consumers in over 60 countries.

In the 1950s and 60s, many people in the developed world felt passionately about the enormous disparities between developed and developing countries, and they believed the system of international trade shut out African, Asian, and South American producers who could not compete with multi-national companies or who came from states that, for political reasons, were not trading with the West. The catchphrase ‘Trade Not Aid’ was used by church groups and trade unions – early supporters of fair trade – who also considered that international aid was either a pittance or a covert form of subjugation. These days, much fair trade does include aid: developed-world volunteers offer their services, and there is free training for producers and their workers.

Tea, coffee, cocoa, cotton, flowers, handicrafts, and gold are all major fair-trade items, with coffee being the most recognisable, found on supermarket shelves and at café chains throughout the developed world.

Although around two million farmers and workers produce fair-trade items, this is a tiny number in relation to total global trade. Still, fair-trade advocates maintain that the system has positively impacted upon many more people worldwide, while the critics claim that if those two million returned to the mainstream trading system, they would receive higher prices for their goods or labour.

Fair trade is supposed to be trade that is fair to producers. Its basic tenet is that developed-world consumers will pay slightly more for end products in the knowledge that developing-world producers have been equitably remunerated, and that the products have been made in decent circumstances. Additionally, the fair-trade system differs from that of the open market because there is a minimum price paid for goods, which may be higher than that of the open market. Secondly, a small premium, earmarked for community development, is added in good years; for example, coffee co-operatives in South America frequently receive an additional 25c per kilogram. Lastly, purchasers of fair-trade products may assist with crop pre-financing or with training of producers and workers, which could take the form of improving product quality, using environmentally friendly fertilisers, or raising literacy. Research has shown that non-fair-trade farmers copy some fair-trade farming practices, and, occasionally, encourage social progress. In exchange for ethical purchase and other assistance, fair-trade producers agree not to use child or slave labour, to adhere to the United Nations Charter on Human Rights, to provide safe workplaces, and to protect the environment despite these not being legally binding in their own countries. However, few non-fair-trade farmers have adopted these practices, viewing them as little more than rich-world conceits.

So that consumers know which products are made under fair-trade conditions, goods are labelled, and, these days, a single European and American umbrella organisation supervises labelling, standardisation, and inspection.

While fair trade is increasing, the system is far from perfect. First and foremost, there are expenses involved in becoming a fair-trade-certified producer, meaning the desperately poor rarely participate, so the very farmers fair-trade advocates originally hoped to support are excluded. Secondly, because conforming to the standards of fair-trade certification is costly, some producers deliberately mislabel their goods. The fair-trade monitoring process is patchy, and unfortunately, around 12% of fair-trade-labelled produce is nothing of the kind. Next, a crop may genuinely be produced under fair-trade conditions, but due to a lack of demand cannot be sold as fair trade, so goes onto the open market, where prices are mostly lower. It is estimated that only between 18-37% of fair-trade output is actually sold as fair trade. Sadly, there is little reliable research on the real relationship between costs incurred and revenue for fair-trade farmers, although empirical evidence suggests that many never realise a profit. Partly, reporting from producers is inadequate, and ways of determining profit may not include credit, harvesting, transport, or processing. Sometimes, the price paid to fair-trade producers is lower than that of the open market, so while a crop may be sold, elsewhere it could have earnt more, or where there are profits, they are often taken by the corporate firms that buy the goods and sell them on to retailers.

There are problems with the developed-world part of the equation too. People who volunteer to work for fair-trade concerns may do so believing they are assisting farmers and communities, whereas their labour serves to enrich middlemen and retailers. Companies involved in West African cocoa production have been criticised for this. In the developed world, the right to use a fair-trade logo is also expensive for packers and retailers, and sometimes a substantial amount of the money received from sale is ploughed back into marketing. In richer parts of the developed world, notably in London, packers and retailers charge high prices for fair-trade products. Consumers imagine they are paying so much because more money is returned to producers, when profit-taking by retailers or packers is a more likely scenario. One UK café chain is known to have passed on 1.6% of the extra 18% it charged for fair-trade coffee to producers. However, this happens with other items at the supermarket or café, so perhaps consumers are naïve to believe fair-traders behave otherwise. In addition, there are struggling farmers in rich countries, too, so some critics think fair-trade associations should certify them. Other critics find the entire fair-trade system flawed – nothing more than a colossal marketing scam – and they would rather assist the genuinely poor in more transparent ways, but this criticism may be overblown since fair trade has endured for and been praised in the developing world itself.

Questions 28-32

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 28-32 on your answer sheet.

28 What was an early slogan about addressing the imbalance between the developed and developing worlds?

…………………….

29 What is probably the most well-known fair-trade commodity?

…………………….

30 According to the writer, in terms of total global trade, what do fair-trade producers represent?

…………………….

31 How do its supporters think fair trade has affected many people?

…………………….

32 What do its critics think fair-trade producers would get if they went back to mainstream trade?

…………………….

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-H, below.

Write the correct letter, A-H, in boxes 33-36 on your answer sheet.

33 Consumers of fair-trade products are happy

34 The fair-trade system may include

35 Some fair-trade practices

36 Fair-trade producers must adopt international employment standards

A loans or training for producers and employees.

B although they may not be obliged to do so in their own country.

C for the various social benefits fair trade brings.

D to pay more for what they see as ethical products.

E has influenced non-fair-trade producers.

F because these are United Nations obligations.

G too much corruption.

H have been adopted by non-fair-trade producers.

Questions 37-40

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 3?

In boxes 37-40 on your answer sheet, write:

37 The fair-trade system assists farmers who are extremely poor.

38 Some produce labelled as fair-trade is in fact not.

39 UK supermarkets and cafés should not charge such high prices for fair-trade items.

40 Fair trade is mainly a marketing ploy and not a valid way of helping the poor.

The Writing test lasts for 60 minutes.

Task 1

Spend about 20 minutes on this task.

The table below gives information about two atolls: Bassas da India, and Ile Europa.

Write a summary of the information. Select and report the main features, and make comparisons where necessary.

Write at least 150 words.

Task 2

Spend about 40 minutes on this task.

Write about the following topic:

Some people believe positive thinking has benefits, while others consider it has drawbacks.

Discuss both these views, and give your own opinion.

Provide reasons for your answer, including relevant examples from your own knowledge or experience.

Write at least 250 words.

PART 1

How might you answer the following questions?

1 Could you tell me what you’re doing at the moment: are you working or studying?

2 What are you studying?

3 What do you like most about your studies?

4 What do you remember about your first day at school / college / university?

5 Now, let’s talk about taking driving lessons. Do you drive?

6 How difficult was it for you to get a driver’s licence?

7 Do you think there should be an upper age limit on drivers? Why? / Why not?

8 Let’s move on to talk about the theatre. How often do you go to the theatre?

9 Why do some people prefer to go to the theatre than to the cinema?

10 What would be the thrills and challenges of being a theatre director?

PART 2

How might you speak about the following topic for two minutes?

I’d like you to tell me about a very good piece of advice someone gave you.

* Who was the person?

* What was the advice?

* Did you take the advice?

And, how do you feel about the experience now?

PART 3

1 First of all, advice about one’s private life.

When are some occasions it’s great to get advice from family members, and when might advice from friends be more useful?

Should school or university teachers advise their students about their private lives?

What qualities does a person need to give sound advice?

2 Now, let’s consider advice about careers.

Who gives advice about careers in your country?

Do you think it is better to choose a career on one’s own, or to take advice from others about the choice?

LISTENING

Section 1: 1. Aarav; 2. Life; 3. 50 / fifty; 4. C; 5. D; 6. space; 7. play; 8. hidden costs; 9. holidays; 10. well informed. Section 2: 11. A; 12. B; 13. B; 14. C; 15. B; 16. shower; 17. share; 18. functional and/& beautiful; 19. 400/four hundred; 20. time. Section 3: 21. A; 22. B; 23. A; 24. C; 25. C; 26. A; 27. Personnel; 28. Supporting documents; 29. Structure; 30. Requirements. Section 4: 31. literary fiction; 32. different; 33. classic; 34. unchallenged // intact; 35. C; 36. A; 37. C; 38. B; 39. C; 40. A.

The highlighted text below is evidence for the answers above.

Narrator : Recording 19.

Practice Listening Test 4.

Section 1. Children’s day care.

You will hear a man and a woman talking about day care for their children.

Read the example.

Angela : Hi Sanjit? How are you?

Sanjit : Pretty well, Angela.

Tom won’t be here for another ten minutes. Shall we have coffee while we’re waiting?

Angela : Why not?

Narrator : The answer is ‘coffee’.

On this occasion only, the first part of the conversation is played twice.

Before you listen again, you have 30 seconds to read questions 1 to 5.

Angela : Hi Sanjit? How are you?

Sanjit : Pretty well, Angela.

Tom won’t be here for another ten minutes. Shall we have coffee while we’re waiting?

Angela : Why not?

How’s your family?

Sanjit : Not too bad, except my son, (1) Aarav, had a cold last week, and then my wife, Navreet, caught it.

Angela : Oh dear.

My daughter, Zoe, had a temperature this morning, and I wasn’t sure whether to send her to day care, but my husband’s away, in Toronto, and I can’t take any more time off myself.

Sanjit : I guess kids get all kinds of things at day care.

Angela : I don’t know. They also build up resistance there.

By the way, I’m sending out invitations for Zoe’s birthday party. How do you spell (1) Aarav?

Sanjit : (1) Double ARAV.

Angela : Thanks.

I’ve never heard the name before. What does it mean?

Sanjit : ‘Peaceful’ or ‘wise’. It’s popular in India because the film stars Twinkle Khanna and Akshay Kumar called their son Aarav.

What does Zoe mean?

Angela : It’s the Greek form of Eve, which was my mother’s name. It means (2) ‘life’.

Sanjit : Nice.

Navreet and I have put Aarav’s name down at a day care centre in East Lindsay, but we’ve heard a few odd things about it, so we’re looking elsewhere. What’s Zoe’s day care like?

Angela : Pretty good. My son went there for two years, and he survived.

Sanjit : If you don’t mind my asking, what does it cost?

Angela : It varies. If you provide things yourself, like diapers and snacks, it’s reasonable, around $30 a day; but, if the centre provides everything, it starts to add up, and can go as high as (3) 50.

Sanjit : I see.

Angela : Also, there are quite a few (8) hidden costs.

Sanjit : Such as?

Angela : Well, the parents are, kind of, competitive. If a child has a birthday, mum or dad is expected to bring a snack for the whole room – (4-5) the day care’s divided into rooms, by age. Right now, Zoe’s in Penguins. Sometimes, I think parents spend a lot of time and money on those birthday snacks.

Sanjit : Once Navreet’s back at work, she may well be too busy.

Angela : Absolutely.

(4-5) Also, if you set a pick-up time, but get there 15 minutes late, the centre fines you $5, and five more dollars for every quarter-hour thereafter.

Sanjit : That’s a bit steep, especially if you were just caught in traffic.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 6 to 10.

Angela : So, tell me about the centre in East Lindsay.

Sanjit : At first, I was impressed: it’s spotless throughout, and the staff seems caring and responsible. I like the fact there’s a decent amount of (6) space, especially outdoors. However, I’m worried that the children aren’t explicitly taught anything – all they do is (7) play. Sure, Aarav’s only one, but, in an eight-hour day, there’s a lot he can learn.

Angela : At Zoe’s day care, there is some structure to the week and some tuition. In (4-5) Penguins, Monday is alphabet day, and Wednesday is numbers. In (4-5) Tigers, Monday’s computer day, and Wednesday’s music.

Sanjit : Computer day?

Angela : Yeah. Parents have to provide tablets for their children when they turn two – another of the (8) hidden costs I was telling you about.

Sanjit : Right.

Angela : But, there’s one good thing at Zoe’s day care: you’re not charged if your child’s off sick for a day. And, as long as you give notice, you can take your child out for (9) holidays, which, again, you don’t pay for. Many centres will only allow a one-month fee-free break in a year.

Sanjit : What’s the hygiene like?

Angela : Good enough. The kids do get things in their hair, which is a bit embarrassing, but supermarkets stock shampoo, and parents are contacted as soon as there’s an outbreak.

Sanjit : (10) Would you say the centre kept parents well informed?

Angela : Yes, I would.

There you go: a reminder about Zoe’s birthday. Her snack can’t contain peanuts because a boy in Penguins has an allergy.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 1.

Narrator : Recording 20.

Section 2. A very small house.

You will hear a woman being interviewed on the radio about living in a very small house.

Before you listen, you have 30 seconds to read questions 11 to 15.

Simon : Welcome to today’s show, coming to you from the home of Charlotte Williams.

Good morning, Charlotte.

Charlotte : Morning Simon.

Simon : Thanks for letting us into your home, which, I believe, has been inundated with guests recently.

Charlotte : Yes, I held my birthday party here.

Simon : Surely that was a squeeze, given (11) your whole house is eight square metres, about the size of my kitchen.

Charlotte : The party was in the garden.

Simon : I understand there’s been an upsurge in interest in the tiny-house movement.

Charlotte : That’s right. Even Oprah has interviewed some of its devotees. (12) We’re no longer the weirdos at the end of the street.

Simon : (12) But you were for some time, weren’t you?

Charlotte : (12) Yes, I was.

I’m sorry to say, I’ve had unpleasant text messages, rubbish strewn across my lawn, and rats put into my water tanks.

Charlotte : (13) But, y’know, when I was a kid, people used to smoke in doctors’ waiting rooms and on airplanes. Once, on a flight to LA, I practically choked. My mother said crossly, ‘Settle down; it’s only smoke.’ Now, of course, no one smokes on airplanes, and my mother is the first person to tell anyone off who lights up in a surgery.

Simon : So, your mother’s one of your fans?

Charlotte : I wouldn’t say that exactly. Anyway, she lives in France.

In my opinion, in the developed world, we all consume too much. (14) I mean, In 1945, the average house in this city for a five-to-seven-person family was 111 square metres; two generations later, it’s twice that size, while the family has only 3.5-to-four people.

Simon : I note you say ‘in the developed world’. Perhaps an immigrant might still think you’re weird. After all, isn’t the American dream to think big?

Charlotte : Yes, one criticism levelled at me is that my lifestyle is anti-American. It’s true that, while working in Mozambique and (15) Vietnam, I was inspired by my neighbours who used few resources.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 16 to 20.

Charlotte : In Mozambique, people use far less water and electricity than here. That’s when I started to live without a fridge or a (16) shower, like the locals. I washed in a basin of water, which I still do.

Simon : I don’t think I could live without a shower!

Charlotte : In Vietnam, many of my neighbours didn’t have a kitchen, but cooked and ate outside. This meant there was life in the streets. Here, my kitchen consists of two elements and that basin. And, as you know, my party was outside. Also, in my part of Ho Chi Minh City, children generally slept in one bedroom. Indeed, children do (17) share more when they’re in small spaces, and they’re less likely to acquire all the junky toys that fill up many American homes.

Simon : But you live alone, Charlotte, and the climate here is rather different.

Charlotte : Sure. My son’s grown up, and my partner lives in Chicago although he visits often.

The climate is cold here, but my heating bill is low because this is a small space. I do still need quilts and winter clothes, which I store under my bed. However, I own two coats while my sister’s got ten.

Simon : If you don’t mind my saying so, Charlotte, isn’t (11) eight square metres rather cramped? Haven’t you had to give up all kinds of things?

Charlotte : Firstly, I have a great view of trees from my bed, so I feel part of nature – of the great expanse of nature. When I lived in a larger house, all I could see were other large houses.

Honestly, I haven’t given up anything. Every single item I now own has to be (18) functional and beautiful. I don’t keep anything out of guilt, because it was a present, or I paid a lot for it. I had 4,000 possessions before moving here; now I’ve got (19) 400.

Simon : What other savings have you made?

Charlotte : I didn’t pay much for this property, so I’m mortgage-free, which means I can work part-time. Without a doubt, the greatest saving I’ve made is of (20) time. I clean my house for one hour a week; in the past, I was a slave to chores and maintenance.

Most people think I live in a tiny house out of poverty or fanaticism when really it’s through choice. I’m just getting on with life.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 2.

Narrator : Recording 21.

Section 3. A business assignment.

You will hear two students discussing an assignment they are doing on Business Plans.

Before you listen, you have 30 seconds to read questions 21 to 26.

Natasha : I don’t know Luca – 800 words don’t seem like many to me.

Luca : Except I’ve only written (21) 450.

Natasha : Why don’t you talk through what you’ve got, and I can suggest where you might add some in?

Luca : I can show you my essay, if you like, on my computer.

Natasha : Telling me about it may be better; it’ll help you clarify what you have, and you’ll probably notice what’s missing as you speak.

So, what is a Business Plan?

Luca : Something that projects ahead for at least three years.

Luca : Well, in essence, it’s…um…

Natasha : (22) An analysis of the current situation a business finds itself in, and a projection of its growth.

Luca : Right.

Natasha : And what else?

Luca : Basically, I suppose…

Natasha : What about the standards a Business Plan creates?

Luca : Oh, yeah. The plan creates standards. And it discusses viability.

Natasha : Indeed.

(23) Who does it provide a tool for?

Luca : (23) Investors. I mean, potential investors.

Let me turn on my computer to type that in.

‘It discusses… viability… and provides… a sales tool for (23) potential… investors.’

Natasha : Good.

Now, what about the five steps involved in creating the plan?

Luca : Five? I wrote down three in the lecture.

One, carry out a situational analysis; two, understand the operating environment; and, three, define business objectives.

Were there any others?

Natasha : I’m sure there were five, but I’ve forgotten them, myself, now.

Luca : Oh, I remember. Something about formulating strategies.

Natasha : Yes. Formulate strategies to follow.

Luca : And five?

Natasha : (24) Design controls to measure success. Though I’ve no idea what those controls might be.

Luca : (24) Me neither.

I don’t have any real-world experience for this course. I’m doing it because my cousin told me it was easy.

Natasha : Anyway, the last thing to note in the essay is that there’s not just one business plan – (25) a company usually composes separate plans for all sections of the master plan. That means another Marketing Plan, another Production Plan etc.

Luca : (26) I’d no idea there was so much planning. How do businesses have any time to actually work?

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 27 to 30.

Natasha : Let’s look at the short answers, now. My friend who took this course last year said the final exam contained the short answers from this assignment and the next one.

Luca : Then, I’d better learn them off by heart.

Natasha : So, without reading from your computer screen, what are the five functions a business can be divided into?

Luca : You mean, MP3F?

Natasha : Yes.

Luca : M for Marketing. The three Ps for Purchasing, Production, and … what’s the last one?

Natasha : (27) Personnel.

Luca : Right, (27) Personnel. And F for Finance.

Natasha : Good.

I see you’ve remembered that the Business Profile and Appendices open and close the plan, but I think your definition of ‘appendices’ is a bit vague.

Luca : What’s wrong with ‘End notes’?

Natasha : Certainly, appendices are found at the end of a plan, but the phrase (28) ‘supporting documents’ might describe them more clearly.

Luca : OK. I’ll write that down.

(28) ‘Sup-por-ting do-cu-ments.’

Natasha : The key here is that there’s support for every section of the plan because an investor wants to see a strong case presented for your business, to know you’re not just making assertions.

Luca : Right.

Natasha : The first few components of your Business Profile look fine. Business Name … Location … Ownership (29) Structure.

Luca : And Business Activity is easy enough to describe.

Natasha : True.

But I’m afraid your Market Entry Strategy and Future Objectives look a little thin.

Luca : The thing is, Natasha, I don’t understand what a Market Entry Strategy is. And Future Objectives seem equally nebulous.

Natasha : I know what you mean.

I see you’ve mentioned Legal (30) Requirements in the Business Profile.

Luca : Don’t you remember, the lecturer said that in today’s environment of tight regulation, without this section in the plan, the whole business could end up being an expensive failure?

Natasha : Oh help. I forgot about Legal (30) Requirements in my profile! Thanks for reminding me.

I’m sorry, Luca, I’ll have to go. Let’s meet again after the tutorial.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 3.

Narrator: : Recording 22.

Section 4. The benefits of literature.

You will hear a lecture on the benefits of reading literature.

Before you listen, you have 45 seconds to read questions 31 to 40.

Lecturer: : Last week, my sixteen-year-old neighbour asked me to look over her essay on the value of reading. I read the text, and was impressed by her elegant prose. But there was one glaring omission. Most of her essay was about how we read or why we read. In my opinion, how or why is far less important than what we read.

No one today would deny that reading improves cognitive intelligence: I bet the top three students here are also the three biggest readers. However, a growing number of experts attribute (31) literary fiction to a reader’s enhanced capacity for emotional as well as cognitive intelligence.

But what are emotional intelligence and literary fiction? Actually, ‘emotional intelligence’ is a phrase popularised by the media; academics, like me, prefer the term ‘Theory of Mind’ or TOM.

TOM is the ability to attribute mental states – beliefs, intentions, desires, pretence, and knowledge – to oneself and others; and, to understand that others have states (32) different from one’s own. Notable deficits in TOM occur in people with schizophrenia, attention deficit and autism spectrum disorders, or with neurotoxicity, due to drug or alcohol abuse.

What is literary fiction? Well, it’s writing considered as (33) classic – winning widespread acclaim, translated into many languages, and enduring over time. Think: Jane Austen, Anton Chekhov, or F. Scott Fitzgerald, and people like Alaa al Aswany, Paulo Cuelho, or Alice Munro.

The vast majority of books, however, are not literary: they’re non-fiction or popular fiction. Non-fiction deals with facts, and popular fiction with formulaic stories. True, in pop fiction, readers go on an emotional journey, often in exotic settings, but, while events may be dramatic, the external and internal lives of characters are predictable. This means readers’ expectations remain (34) unchallenged; their view of the world is (34) intact.

By contrast, literary fiction focuses on the psychological states of characters and on their complex interpersonal relationships. Some writers adopt a technique called ‘stream of consciousness’ in which they minutely describe what is occurring in a character’s head; others only allude to a character’s state of mind. In the first instance, readers may be exposed to ways of perceiving the world quite different from their own. In the second, their need to interpret intentions or motivations expands their emotional problem-solving capacity. So, despite being set in the real, often humdrum, world, literary works defy expectations by challenging prejudices and undermining stereotypes.

Five experiments by the New York academics (35) David Kidd and Emanuele Castano have confirmed this. They invited hundreds of online participants to read extracts from non-fiction, popular fiction, or literary fiction; or, not to read anything at all. On cognitive and emotional tests, Kidd and Castano demonstrated that readers of (31) literary fiction performed better compared to readers of other genres or those who did not read.

(36) It’s conceivable that including literary fiction in the daily routine of prisons, as well as in schools and universities, would bear fruit. It is already known that those in the correctional system who receive credits towards liberal arts college degrees survive better on release. Medicating children with autism or ADHD has been fashionable, but having them read literature may improve their conditions.

There are some lesser benefits to reading literary fiction. Firstly, it encourages discipline and connectedness. Discipline because the language or style may be complex, and a length of time is needed to finish it. Connectedness because readers identify strongly with great characters. (37) Think about a generation of children who read the seven Harry Potter books, devoting around 40 hours to them. An equivalent amount of time spent watching a TV series would not generate an equivalent emotional response. Secondly, neuroscientists, in 2013, discovered enhanced neural activity in subjects who read fine literature daily. Those who read just before falling asleep were more likely to awaken soothed and focused, unlike TV viewers.

So, why aren’t schools, universities, and prisons insisting on more literary fiction? Why aren’t sales of Nobel-prizewinners soaring? Some say, life is too demanding. (38) Common Sense Media, a San Francisco, based non-profit organisation, produced a report called ‘Why aren’t teens reading?’ It showed that, currently, 27% of seventeen-year-olds read for pleasure almost every day, whereas, in 1984, 31% did. Thirty years ago, nine percent of seventeen-year-olds said they seldom or never read for pleasure. By 2014, those figures had tripled to 27%. (39) Many respondents attribute this change to needing time for other life skills, but (40) it is my argument that, as complexity increases, the young become more adept at dealing with it when they read literary fiction.

So, did I suggest my neighbour redraft her essay? No. I gave her a copy of The Little Prince, a French classic from 1943, and asked her to pass it on to a friend when she’d finished.

Narrator: That is the end of the Listening test.

You now have ten minutes to transfer your answers to your answer sheet.

READING: Passage 1: 1. iv; 2. i; 3. v; 4. ix; 5. vii; 6. ii; 7. cloths; 8. 15th / Fifteenth; 9. background; 10. youth; 11. Realism; 12. 1965; 13. D&E / E&D. Passage 2: 14. T/True; 15. T/True; 16. NG/Not Given; 17. F/False; 18. C; 19. B; 20. A; 21. B; 22. G; 23. I; 24. F; 25. A; 26. E; 27. H. Passage 3: 28. ‘Trade Not Aid’ (Quotation marks optional); 29. Coffee; 30. A tiny number (Must include ‘A’); 31. Positively; 32. Higher prices; 33. D; 34. A; 35. H; 36. B; 37. N/No; 38. Y/Yes; 39. NG/Not Given; 40. N/No.

The highlighted text below is evidence for the answers above.

If there is a question where ‘Not given’ is the answer, no evidence can be found, so there is no highlighted text.

Red in Russian art

A In Old Slavonic, a language that precedes Russian, ‘red’ has a similar root to the words ‘good’ and ‘beautiful’. Indeed, until the 20th century, Krasnaya Ploshchad, or Red Square, in central Moscow, was understood by locals as ‘Beautiful Square’. For Russians, red has great symbolic meaning, being associated with goodness, beauty, warmth, (12-13) vitality, jubilation, (12-13) faith, love, salvation, and power.

B (1) Because red is a long-wave colour at the end of the spectrum, its effect on a viewer is striking: it appears closer than colours with shorter waves, like green, and it also intensifies colours placed alongside it, which accounts for the popularity of red and green combinations in Russian painting.

C (2) Russians love red. In the applied arts, it predominates: bowls, boxes, trays, wooden spoons, and distaffs for spinning all feature red, as do children’s toys, decorative figurines, Easter eggs, embroidered (7) cloths, and garments. In the fine arts, red, white, and gold form the basis of much icon painting.

D (3) In pre-Christian times, red symbolised blood. Christianity adopted the same symbolism; red represented Christ or saints in their purification or martyrdom. The colour green, meantime, signified wisdom, while white showed a person reborn as a Christian. Thus, in a famous (8) 15th-century icon from the city of Novgorod, Saint George and the Dragon, red-dressed George sports a green cape, and rides a pure-white stallion. In many icons, Christ and the angels appear in a blaze of red, and the mother of Christ can be identified by her long red veil. In an often-reproduced icon from Yaroslavl, the Archangel Michael wears a brilliant red cloak. However, the fires of Hell that burn sinners are also red, like those in an icon from Pskov.

E (4) A red (9) background for major figures in icons became the norm in representations of mortal beings, partly to add vibrancy to skin tones, and one fine example of this is a portrait of Nikolai Gogol, the writer, from the early 1840s. (4) When wealthy aristocrats wished to be remembered for posterity, they were often depicted in dashing red velvet coats, emulating the cloaks of saints, as in the portraits of Jakob Turgenev in 1696, or of Admiral Ivan Talyzin in the mid-1760s. Portraits of women in Russian art are rare, but the Princess Yekaterina Golitsyna, painted in the early 1800s, wears a fabulous red shawl.

Common people do not appear frequently in Russian fine art until the 19th century, when their peasant costumes are often white with red embroidery, and their elaborate headdresses and scarves are red. (4) The women in the 1915 painting, Visiting, by Abram Arkhipov seem aflame with life: their dresses are red; their cheeks are red; and, a jug of vermillion lingonberry cordial glows on the table beside them.

Russian avant-garde painters of the early 20th century are famous beyond Russia as some of the greatest abstract artists. Principal among these are Nathan Altman, Natalia Goncharova, Wassily Kandinsky, and Kazimir Malevich, who painted the ground-breaking White on white as well as Red Square, which is all the more compelling because it isn’t quite square. Malevich used primary colours, with red prominent, in much of his mature work. Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin is hailed as a genius at home, but less well-known abroad; his style is often surreal, and his palette is restricted to the many hues of red, contrasting with green or blue. The head in his 1915 Head of a (10) youth is entirely red, while his 1925 painting, Fantasy, shows a man in blue, on a larger-than-life all-red horse, with a blue town in blue mountains behind.

F (5) Part of the enthusiasm for red in the early 20th century was due to the rise of the political movement, communism. Red had first been used as a symbol of revolution in France in the late 18th century. The Russian army from 1918-45 called itself the Red Army to continue this revolutionary tradition, (5) and the flag of the Soviet Union was the Red Flag.

Soviet poster artists and book illustrators also used swathes of red. (5) Some Social (11) Realist painters have been discredited for their political associations, but their art was potent, and a viewer cannot help but be moved by Nikolai Rutkovsky’s 1934 Stalin at Kirov’s coffin. Likewise, Alexander Gerasimov’s 1942 Hymn to October or Dmitry Zhilinsky’s (12) 1965 Gymnasts of the USSR stand on their own as memorable paintings, both of which include plenty of red.

G (6) In English, red has many negative connotations – red for debt, a red card for football fouls, or a red-light district – but in Russian, red is beautiful, (12-13) vivacious, spiritual, and revolutionary. And Russian art contains countless examples of its power.

Myths and Misnomers

A buttercup is a small, bright yellow flower; a butternut is a yellow-fleshed squash; and, there is also a butter bean. (14) The origin of the word ‘butterfly’ may be similar to these plants – a creature with wings the colour of butter – (15) but a more fanciful notion is that ‘flutterby’ was misspelt by an early English scribe since a butterfly’s method of flight is to flutter by. Etymologists may not concur, but entomologists agree with each other that butterflies belong to the order of Lepidoptera, which includes moths, and that ‘lepidoptera’ accurately describes the insects since ‘lepis’ means ‘scale’ and ‘pteron’ means ‘wing’ in Greek.

(17) Until recently, butterflies were prized for their evanescence – people believed that adults lived for a single day; it is now known this is untrue, and some, like monarch butterflies, live for up to nine months.

Butterflies versus Moths

(18) Butterflies and moths have some similarities: as adults, both have four membranous wings covered in minute scales, attached to a short thorax and a longer abdomen with three pairs of legs. (18) They have moderately large heads, long antennae, and (18) compound eyes; tiny palps for smell; and, a curling proboscis for sucking nectar. Otherwise their size, colouration, and lifecycles are the same.

Fewer than 1% of all insects are butterflies, but they hold a special place in the popular imagination as being beautiful and benign. (19) Views of moths, however, are less kind since some live indoors and feast on cloth; others damage crops; and, most commit suicide, being nocturnal and drawn to artificial light. (20) There are other differences between butterflies and moths; for example, when resting, the former fold their wings vertically above their bodies, while the latter lay theirs flat. Significantly, butterfly antennae thicken slightly towards their tips, whereas (21) moth antennae end in something that looks like a V-shaped TV aerial.

The Monarch Butterfly

Originating in (22) North America, the black-orange-and-white monarch butterfly lives as far away as Australia and New Zealand, and for many children it represents a lesson in metamorphosis, which can even be viewed in one’s living room if a pupa is brought indoors.

It is easy to identify the four stages of a monarch’s lifecycle – egg, larva, pupa, and adult – but there are really seven. This is because, unlike vertebrates, insects do not have an internal skeleton, but a tough outer covering called an exoskeleton. This is often shell-like and sometimes indigestible by predators. Muscles are hinged to its inside. As the insect grows, however, the constraining exoskeleton must be moulted, and a monarch butterfly undergoes (23) seven moults, including four as a larva.

Temperature dramatically affects butterfly growth: in warm weather, a monarch may go through its seven moults in just over a month. Time spent inside the egg, for instance, may last three to four days in 25° Celsius, but in 18°, the whole process may take closer to eight weeks, with time inside the egg eight to twelve days. Naturally, longer development means lower populations due to increased predation.

A reliable food supply influences survival, and the female monarch butterfly is able to sniff out one particular plant its young can feed off – (24) milkweed or swan plant. There are a few other plants larvae can eat, but they will resort to these only if the milkweed is exhausted and alternatives are very close by. Moreover, a female butterfly may be conscious of the size of the milkweed on which she lays her eggs since she spaces them, but another butterfly may deposit on the same plant, lessening everyone’s chance of survival.

While many other butterflies are close to extinction due to pollution or dwindling habitat, the global numbers of monarchs have decreased in the past two decades, but less dramatically.

Monarch larvae absorb toxins from milkweed that render them poisonous to most avian predators who attack them. Insect predators, like aphids, flies, and wasps, seem unaffected by the poison, and are therefore common. A recent disturbing occurrence is the death of monarch eggs and larvae from (25) bacterial infection.

Another reason for population decline is reduced wintering conditions. Like many birds, monarch butterflies migrate to warmer climates in winter, often flying extremely long distances, for example, from Canada to southern California or northern Mexico, or from southern Australia to the tropical north. They also spend some time in semi-hibernation in dense colonies deep in forests. In isolated New Zealand, monarchs do not migrate, instead finding particular trees on which to congregate. In some parts of California, wintering sites are protected, but in (26) Mexico, much of the forest is being logged, and the insects are in grave danger.

Milkweed is native to southern Africa and North America, but it is easy to grow in suburban gardens. Its swan-shaped seedpods contain fluffy seeds used in the 19th century to stuff mattresses, pillows, and lifejackets. After milkweed had hitched a lift on sailing ships around the Pacific, the American butterflies followed with Hawaii seeing their permanent arrival in 1840, Samoa in 1867, Australia in 1870, and New Zealand in 1873. As butterfly numbers decline sharply in the Americas, it may be (27) these Pacific outposts that save the monarch.

The fair-trade movement began in Europe in earnest in the post-war period, but only in the last 25 years has it grown to include producers and consumers in over 60 countries.

In the 1950s and 60s, many people in the developed world felt passionately about the enormous disparities between developed and developing countries, and they believed the system of international trade shut out African, Asian, and South American producers who could not compete with multi-national companies or who came from states that, for political reasons, were not trading with the West. The catchphrase (28) ‘Trade Not Aid’ was used by church groups and trade unions – early supporters of fair trade – who also considered that international aid was either a pittance or a covert form of subjugation. These days, much fair trade does include aid: developed-world volunteers offer their services, and there is free training for producers and their workers.

Tea, coffee, cocoa, cotton, flowers, handicrafts, and gold are all major fair-trade items, with (29) coffee being the most recognisable, found on supermarket shelves and at café chains throughout the developed world.

Although around two million farmers and workers produce fair-trade items, this is (30) a tiny number in relation to total global trade. Still, fair-trade advocates maintain that the system has (31) positively impacted upon many more people worldwide, while the critics claim that if those two million returned to the mainstream trading system, they would receive (32) higher prices for their goods or labour.

Fair trade is supposed to be trade that is fair to producers. (33) Its basic tenet is that developed-world consumers will pay slightly more for end products in the knowledge that developing-world producers have been equitably remunerated, and that the products have been made in decent circumstances. Additionally, the fair-trade system differs from that of the open market because there is a minimum price paid for goods, which may be higher than that of the open market. Secondly, a small premium, earmarked for community development, is added in good years; for example, coffee co-operatives in South America frequently receive an additional 25c per kilogram. (34) Lastly, purchasers of fair-trade products may assist with crop pre-financing or with training of producers and workers, which could take the form of improving product quality, using environmentally friendly fertilisers, or raising literacy. (35) Research has shown that non-fair-trade farmers copy some fair-trade farming practices, and, occasionally, encourage social progress. In exchange for ethical purchase and other assistance, (36) fair-trade producers agree not to use child or slave labour, to adhere to the United Nations Charter on Human Rights, to provide safe workplaces, and to protect the environment (36) despite these not being legally binding in their own countries. However, few non-fair-trade farmers have adopted these practices, viewing them as little more than rich-world conceits.

So that consumers know which products are made under fair-trade conditions, goods are labelled, and, these days, a single European and American umbrella organisation supervises labelling, standardisation, and inspection.

While fair trade is increasing, the system is far from perfect. First and foremost, (37) there are expenses involved in becoming a fair-trade-certified producer, meaning the desperately poor rarely participate, (37) so the very farmers fair-trade advocates originally hoped to support are excluded. Secondly, because conforming to the standards of fair-trade certification is costly, (38) some producers deliberately mislabel their goods. The fair-trade monitoring process is patchy, (38) and unfortunately, around 12% of fair-trade-labelled produce is nothing of the kind. Next, a crop may genuinely be produced under fair-trade conditions, but due to a lack of demand cannot be sold as fair trade, so goes onto the open market, where prices are mostly lower. It is estimated that only between 18-37% of fair-trade output is actually sold as fair trade. Sadly, there is little reliable research on the real relationship between costs incurred and revenue for fair-trade farmers, although empirical evidence suggests that many never realise a profit. Partly, reporting from producers is inadequate, and ways of determining profit may not include credit, harvesting, transport, or processing. Sometimes, the price paid to fair-trade producers is lower than that of the open market, so while a crop may be sold, elsewhere it could have earnt more, or where there are profits, they are often taken by the corporate firms that buy the goods and sell them on to retailers.

There are problems with the developed-world part of the equation too. People who volunteer to work for fair-trade concerns may do so believing they are assisting farmers and communities, whereas their labour serves to enrich middlemen and retailers. Companies involved in West African cocoa production have been criticised for this. In the developed world, the right to use a fair-trade logo is also expensive for packers and retailers, and sometimes a substantial amount of the money received from sale is ploughed back into marketing. In richer parts of the developed world, notably in London, packers and retailers charge high prices for fair-trade products. (39) Consumers imagine they are paying so much because more money is returned to producers, when profit-taking by retailers or packers is a more likely scenario. One UK café chain is known to have passed on 1.6% of the extra 18% it charged for fair-trade coffee to producers. However, this happens with other items at the supermarket or café, so perhaps consumers are naïve to believe fair-traders behave otherwise. In addition, there are struggling farmers in rich countries, too, so some critics think fair-trade associations should certify them. (40) Other critics find the entire fair-trade system flawed – nothing more than a colossal marketing scam – and they would rather assist the genuinely poor in more transparent ways, but this criticism may be overblown since fair trade has endured for and been praised in the developing world itself.

The atolls Bassas da India and Ile Europa lie between Mozambique and Madagascar. They are relatively small: Bassas da India is around 12 kilometres in diameter, with a coastline of 35.2 km; Ile Europa is six kilometres in diameter, with a 22.2 km coastline. Both have been part of the French Southern and Antarctic Lands since 1897 although they are also claimed by Madagascar. Both have been the cause of numerous shipwrecks. Since Bassas da India, a coral formation, is almost all submerged at high tide, it presents a considerable danger to navigation.

Otherwise, the atolls are rather different. Bassas da India is uninhabited as it is mainly lagoon. The reef is uncovered for only six hours each day, around low tide, and the rocky islets permanently above sea level have no vegetation. Ile Europe has a lagoon covering approximately one third of its area. Vegetation includes forest, grass, scrub, and extensive mangroves. Famous for its nesting sites for many bird species and green turtles, introduced goats, rats, sisal and hemp, may pose a threat. Ile Europe was farmed by the French between 1860 and 1920, but currently has no permanent civilian population; instead, it is used by the military, by meteorologists, and other scientists. (205 words)

Task 2

The concept of positive thinking has been around for many years. Some people believe that if we focus our minds positively, then everything will be all right; that, by being optimistic we will have happy, carefree existences, be healthier, and live longer.

Thinking positively inspires us to endure in adversity, gives us a sense of wellbeing, and reduces anxieties. If we tell ourselves we ‘can do it’, then any negative feelings of not being able to do something will disappear.

By assuring ourselves we can achieve, then, we become more motivated and take the initiative. Say, for example, you have just been offered a promotion at work whereby you need to learn more skills, assume more responsibility, and supervise a much larger staff. If you have negative thoughts about your ability to cope, then you may refuse the promotion. However, if you are more optimistic and tell yourself it is just a matter of easing into the job, learning along the way as others have done before you, you will accept the challenge. Naturally, you will be better off financially in your new position. Positive thinking, then, is what is in the mind.

However, I think that people who are always optimistic without considering possible pitfalls are living in a dream world, avoiding realistically assessing issues and problems. I think our lives are governed more by how we feel and act rather than by just thinking positively about every issue. We need to feel positive about an issue before making a decision to act, not just think everything will be all right, without weighing the pros and cons. Thus positive thinking can have its drawbacks.

An overly optimistic person will not always face facts, and is not prepared to deal with life’s crises. Just thinking rich won’t make anyone rich; not accepting that a relative or friend is dying won’t make him or her well again; a hurricane heading our way won’t stop in its path. There are times when we have to prepare for the worst – financially, socially, and environmentally – and act accordingly. Although positive thinking is a useful attitude to have and has many benefits, we must also weigh up the negatives, looking at any opposing implications, so that we have a balanced view of life. (378 words)

1An atoll consists of a ring-shaped coral reef around a lagoon. It is the visible part of an extinct undersea volcano that has been built up by marine organisms.

2c = circa or ‘about’