Firstly, tear out the Test 5 Listening / Reading Answer Sheet at the back of this book.

The Listening test lasts for about 20 minutes.

Write your answers on the pages below as you listen. After Section 4 has finished, you have ten minutes to transfer your answers to your Listening Answer Sheet. You will need to time yourself for this transfer.

After checking your answers on pp 190-194, go to page 9 for the raw-score conversion table.

PLAY RECORDING #23.

PLAY RECORDING #23.

SECTION 1 Questions 1-10

JOINING UP

Questions 1-4

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

Example The tour takes

A 5-10 minutes.

B 10-20 minutes.

C 20-30 minutes. √

1 The visitors found out about the facility from

A an online review.

B a new sign on the street.

C a personal recommendation.

2 According to the guide, people stop going to a pool or gym because

A it becomes too expensive.

B they lack motivation.

C they run out of time.

3 The temperature, in Celsius, of the main pool is

A 25°

B 27°

C 31°

4 Louise apologises to Terry because she thought he was

A unable to swim.

B Charlie’s father.

C from another country.

Complete the table below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS OR A NUMBER for each answer.

PLAY RECORDING #24.

PLAY RECORDING #24.

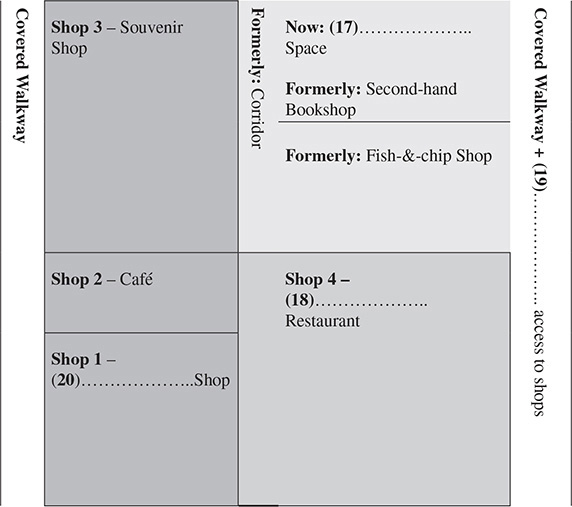

SECTION 2 Questions 11-20

WHARF REDEVELOPMENT

Questions 11-16

Classify the following plans that Cato and Brown or the local council

A wants included.

B is considering.

C has rejected.

Write the correct letter, A, B, or C, on your answer sheet.

11 Another floor

12 A jetty for water taxis

13 A long canopy

14 A long bus shelter

15 The corridor

16 New posts and walkways

Label the plan.

Write ONE WORD ONLY for each answer.

PLAY RECORDING #25.

PLAY RECORDING #25.

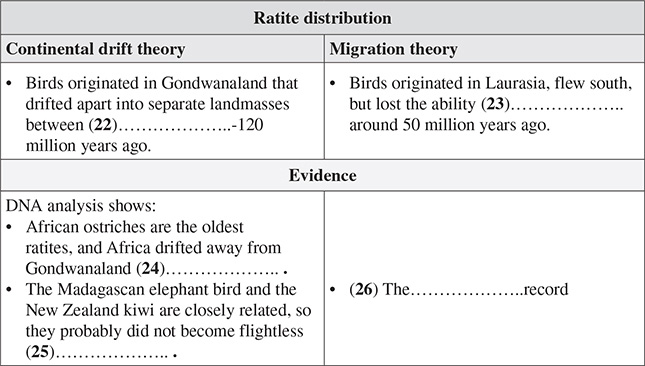

SECTION 3 Questions 21-30

POST-GRADUATE RESEARCH

Question 21

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

21 How did Marcus feel about working in a laboratory in South Africa?

A He absolutely loved it.

B He mostly enjoyed it.

C He didn’t really like it.

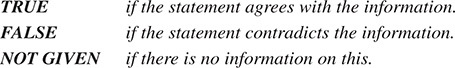

Complete the table below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS OR A NUMBER for each answer.

Which problems did Vanessa encounter with her thesis?

Choose FOUR answers, and write the correct letter, A-H, next to questions 27-30.

A Her online discussion group was too time-consuming.

B Her maths was too poor for statistical analysis.

C She did not finalise her topic for a long time.

D She was not allowed to interview some patients.

E She had to work in a hospital while studying.

F She was unfamiliar with regression analysis.

G Her sample was too small for quantitative analysis.

H Results from her survey were all rather similar.

PLAY RECORDING #26.

PLAY RECORDING #26.

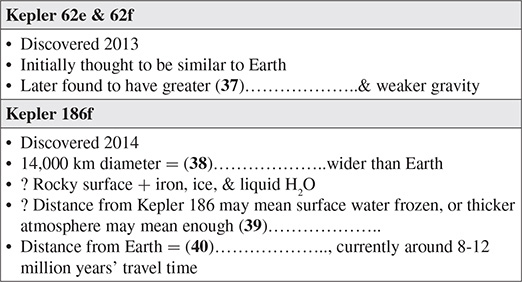

SECTION 4 Questions 31-40

EARTH’S COUSIN

Questions 31-33

Answer the questions below.

Write NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS for each answer.

31 In contrast to previous ones, what is the focus of the Kepler Mission?

………………..………………..

32 What is the area called between a star and its planet where humans could live?

………………..………………..

33 For which development is Johannes Kepler most renowned?

………………..………………..

Questions 34-36

Choose the correct letter, A, B, or C.

34 What does the Kepler photometer record?

A Light emitted from stars in one area of the galaxy

B The age of thousands of distant planets

C The distance between Cygnus and Lyrae and Earth

35 What level of sensitivity does the photometer have?

A A moderate level

B A high level

C An extremely high level

36 Why do scientists measure light from behind a new planet?

A To determine the composition of its atmosphere

B To discover whether liquid water could exist there

C To test the laws of physics and chemistry

Complete the notes below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS AND A NUMBER for each answer.

Firstly, turn over the Test 5 Listening Answer Sheet you used earlier to write your Reading answers on the back.

The Reading test lasts exactly 60 minutes.

Certainly, make any marks on the pages below, but transfer your answers to the answer sheet as you read since there is no extra time at the end to do so.

After checking your answers on pp 194-197, go to page 9 for the raw-score conversion table.

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13, based on Passage 1 below.

Rice is a tall grass with a drooping panicle that contains numerous edible grains, and has been cultivated in China for more than 6,000 years. A staple throughout Asia and large parts of Africa, it is now grown in flooded paddy fields from sea level to high mountains and harvested three times a year. According to the Food and Health Organisation of the United Nations, around four billion people currently receive a fifth of their calories from rice.

Recently, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have slightly reduced rice consumption due to the adoption of more western diets, but almost all other countries have raised their consumption due to population increase. Yet, since 1984, there have been diminishing rice yields around the world.

From the 1950s to the early 1960s, rice production was also suffering: India was on the brink of famine, and China was already experiencing one. In the late 1950s, Norman Borlaug, an American plant pathologist, began advising Punjab State in northwestern India to grow a new semi-dwarf variety of wheat. This was so successful that, in 1962, a semi-dwarf variety of rice, called IR8, developed by the Philippine International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), was planted throughout Southeast Asia and India. This semi-dwarf variety heralded the Green Revolution, which saved the lives of millions of people by almost doubling rice yields: from 1.9 metric tons per hectare in 1950-64, to 3.5 metric tons in 1985-98.

IR8 survived because, as a semi-dwarf, it only grows to a moderate height, and it does not thin out, keel over, and drown like traditional varieties. Furthermore, its short thick stem is able to absorb chemical fertilisers, but, as stem growth is limited, the plant expends energy on producing a large panicle of heavy seeds, ensuring a greater crop.

However, even with a massive increase in rice production, semi-dwarf varieties managed to keep up with population growth for only ten years. In Africa, where rice consumption is rising by 20% annually, and where one third of the population now depends on the cereal, this is disturbing. At the current rate, within the next 20 years, rice will surpass maize as the major source of calories on that continent. Meantime, even in ideal circumstances, paddies worldwide are not producing what they once did, for reasons largely unknown to science. An average 0.8% fall in yields has been noted in rich rice-growing regions; in less ideal ones, flood, drought and salinity have meant yields have fallen drastically, sometimes up to 40%.

The sequencing of the rice genome took place in 2005, after which the IRRI developed genetically modified flood-resistant varieties of rice, called Sub 1, which produce up to four times more edible grain than non-modified strains. In 2010, a handful of farmers worldwide were planting IRRI Sub 1 rice; now, over five million are doing so. Currently, drought- and salt-resistent varieties are being trialled since most rice is grown in the great river basins of the Brahmaputra, the Irrawaddy, and the Mekong that are all drying up or becoming far saltier.

With global warming, many rice-growing regions are hotter than 20 years ago. Nearly all varieties of rice, including IR8, flower in the afternoon, but the anthers – little sacs that contain male pollen – wither and die in soaring temperatures. IRRI scientists have identified one variety of rice, known as Odisha, that flowers in the early morning, and they are in the process of genetically modifying IR8 so it contains Odisha-flowering genes, although it may be some time before this is released.

While there is a clear need for more rice, many states and countries seem less keen to influence agricultural policy directly than they were in the past. Some believe rice demand will dip in wealthier places, as occurred in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan; others consider it more prudent to devote resources to tackling obesity or to limiting intensive farming that is environmentally destructive.

Some experts say where there is state intervention it should take the form of reducing subsidies to rice farmers to stimulate production; others propose that small land holdings should be consolidated into more economically viable ones. There is no denying that land reform is pressing, but many governments shy away from it, fearing losses at the ballot box, all the while knowing that rural populations are heading for the city in droves anyway. And, as they do so, cities expand, eating up fertile land for food production.

One can only hope that the IRRI and other research institutions will spearhead half a dozen mini green revolutions, independently of uncommitted states.

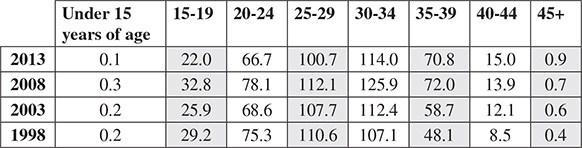

Questions 1-5

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1?

In boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet, write:

1 Rice is only grown at a low elevation.

2 Rice has been cultivated in Africa for 3,000 years.

3 Since 1984, rice yields have decreased due to infestations of pests.

4 Norman Borlaug believed Punjabi farmers should grow semi-dwarf rice.

5 The Green Revolution increased rice yields by around 100%.

Complete the notes below.

Choose ONE WORD AND / OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 6-11 on your answer sheet.

Questions 12-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 12-13 on your answer sheet.

12 States are more interested in……than stimulating rice production.

A increasing wheat production

B reducing farm subsidies

C confronting obesity

D consolidating land holdings

13 ……disappearing as urbanisation speeds up.

A Intensive farming is

B Fertile land is

C Clean water is

D Agricultural institutes are

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-26, based on Passage 2 below.

A New Perspective on Bacteria

A Microbes are organisms too small to be seen by the naked eye, including bacteria, blue-green algae, yeasts, fungi, viruses, and viroids.

A large, diverse group, almost all bacteria are between one and ten µ1 (larger ones reach 0.5 mm). Generally single-celled, with a distinctive cellular structure lacking a true nucleus, most bacterial genetic information is carried on a DNA loop in the cytoplasm2 with the membrane possessing some nuclear properties.

There are three main kinds of bacteria – spherical, rod-like, and spiral – known by their Latin names of coccus, bacillus, and spirillum. Bacteria occur alone, in pairs, clusters, chains, or more complex configurations. Some live where oxygen is present; others, where it is absent.

The relationship between bacteria and their hosts is symbiotic, benefitting both organisms, or the hosts may be destroyed by parasitic or disease-causing bacteria.

B In general, humans view bacteria suspiciously, yet it is now thought they partly owe their existence to microbes living long, long ago.

During photosynthesis, plants produce oxygen that humans need to fuel blood cells. Most geologists believe the early atmosphere on Earth contained very little oxygen until around 2½ billion years ago, when microbes bloomed. Ancestral forms of cyanobacteria, for example, evolved into chloroplasts – the cells that carry out photosynthesis. Once plants inhabited the oceans, oxygen levels rose dramatically, so complex life forms could eventually be sustained.

The air humans breathe today is oxygen-rich, and the majority of airborne microbes are harmless, but the air does contain industrial pollutants, allergens, and infectious microbes or pathogens that cause illness.

C The fact is that scientists barely understand microbes. Bacteria have been proven to exist only in the past 350 years; viruses were discovered just over 100 years ago, but in the past three decades, the ubiquity of microbes has been established with bacteria found kilometres below the Earth’s crust and in the upper atmosphere. Surprisingly, they survive in dry deserts and the frozen reaches of Antarctica; they dwell in rain and snow clouds, as well as inside every living creature.

Air samples taken in 2006 from two cities in Texas contained at least 1,800 distinct species of bacteria, making the air as rich as the soil. These species originated both in Texas and as far away as western China. It now seems that the number of microbe species far exceeds the number of stars.

D Inside every human being there are trillions of bacteria with their weight estimated at 1.36 kg in an average adult, or about as heavy as the brain. Although tiny, 90% of cells in a human are bacterial. With around eight million genes, these bacteria outnumber genes in human cells by 300 times.

The large intestine contains the most bacteria – almost 34,000 species – but the crook of the elbow harbours over 2,000 species. Many bacteria are helpful: digesting food; aiding the immune system; creating moisturiser; and, manufacturing vitamins. Some have highly specialised functions, like Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, which breaks down plant starch, so an infant can make the transition from mother’s milk to a more varied diet.

Undeniably, some bacteria are life-threatening. One, known as golden staph, Staphylococcus aureus, plagues hospitals, where it infects instruments and devours human tissue until patients die from toxic shock. Worse, it is still resistant to antibiotics.

E Antibiotics themselves are bacteria. In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered that a mould in his laboratory produced a chemical he named penicillin. In 1951, William Bouw collected soil from the jungles of Borneo that eventually became vancomycin. Pharmaceutical companies still hunt for beneficial bacteria, but Michael Fischbach from University of California believes that the human body itself is a ready supply.

F Scientific ignorance about bacteria is largely due to an inability to cultivate many of them in a laboratory, but recent DNA sequencing has meant populations can be analysed by computer program without having to grow them.

Fischbach and his team have created and trained a computer program to identify gene clusters in microbial DNA sequences that might produce useful molecules. Having collected microbial DNA from 242 healthy human volunteers, the scientists sequenced the genomes of 2,340 different species of microbes, most of which were completely new discoveries.

In searching the gene clusters, Fischbach et al found 3,118 common ones that could be used in pharmaceuticals, for example, a gene cluster from the bacterium Lactobacillus gasseri, successfully reared in the lab, produced a molecule they named lactocillin. Later, they discovered the structure of this was very similar to an antibiotic, LFF571, undergoing clinical trials by a major pharmaceutical company. To date, lactocillin has killed harmful bacteria, so it may also be a reliable antibiotic.

G Naturally, the path to patenting medicine is strewn with failures, but, since bacteria have been living inside humans for millions of years, they are probably safe to reintroduce in new combinations and in large amounts.

Undoubtedly, the fight against pathogens, like golden staph, must continue, but as scientists learn more about microbes, respect and excitement for them grows, and their positive applications become ever more probable.

Questions 14-18

Passage 2 has seven sections, A-G.

Which section contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-G, in boxes 14-18 on your answer sheet.

NB: Any section can be chosen more than once.

14 examples of bacteria as patented medicine

15 a description of bacteria

16 gene cluster detection and culture

17 humans are teeming with bacteria

18 Fischbach’s hypothesis

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 19-22 on your answer sheet.

19 What do almost all bacteria share?

A Their simple configurations

B Their cellular organisation

C Their survival without oxygen

D Their parasitic nature

20 From the suffix ‘-bacillus’, what shape would you expect the bacterium Paenibacillus to be?

A spherical

B rod-like

C spiral

D amorphous

21 Why were ancient bacteria invaluable to humans?

A They contributed to higher levels of oxygen.

B They reduced widespread industrial pollution.

C They protected humans from intestinal ailments.

D They provided scientists with antibiotics.

22 How prevalent are microbes?

A Not at all

B Somewhat

C Very

D Extremely

Questions 23-26

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet.

23 Which organ does the total weight of bacteria in a human body equal?

…………………….

24 Roughly how many bacterial species live in a human’s large intestine?

…………………….

25 In Fischbach’s view, where might useful bacteria come from in the future?

…………………….

26 What do some scientists now feel towards microbes?

…………………….

Spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27-40, based on Passage 3 below.

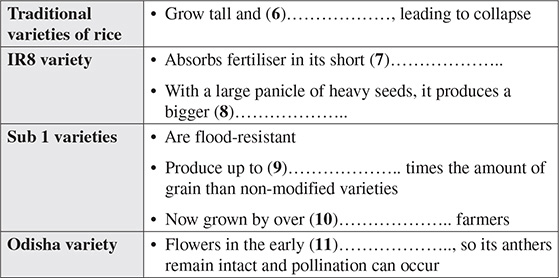

In the last century, Vikings have been perceived in numerous different ways – vilified as conquerors and romanticised as adventurers. How Vikings have been employed in nation-building is a topic of some interest.

In English, Vikings are also known as Norse or Norsemen. Their language greatly influenced English, with the nouns, ‘Hell’, ‘husband’, ‘law’, and ‘window’, and the verbs, ‘blunder’, ‘snub’, ‘take’, and ‘want’, all coming from Old Norse. However, the origins of the word ‘Viking’, itself, are obscure: it may mean ‘a Scandinavian pirate’, or it may refer to ‘an inlet’, or a place called Vik, in modern-day Norway, from where the pirates came. These various names – Vikings, Norse, or Norsemen, and doubts about the very word ‘Viking’ suggest historical confusion.

Loosely speaking, the Viking Age endured from the late eighth to the mid-eleventh centuries. Vikings sailed to England in AD 793 to storm coastal monasteries, and subsequently large swathes of England fell under Viking rule – indeed several Viking kings sat on the English throne. It is generally agreed that the Battle of Hastings, in 1066, when the Norman French invaded, marks the end of the English Viking Age, but the Irish Viking age ended earlier, while Viking colonies in Iceland and Greenland did not dissolve until around AD 1500.

How much territory Vikings controlled is also in dispute – Scandinavia and Western Europe certainly, but their reach east and south is uncertain. They plundered and settled down the Volga and Dnieper rivers, and traded with modern-day Istanbul, but the archaeological record has yet to verify that Vikings raided as far away as Northwest Africa, as some writers claim.

The issue of control and extent is complex because many Vikings did not return to Scandinavia after raiding but assimilated into local populations, often becoming Christian. To some degree, the Viking Age is defined by religion. Initially, Vikings were polytheists, believing in many gods, but by the end of the age, they had permanently accepted a new monotheistic religious system – Christianity.

This transition from so-called pagan plunderers to civilised Christians is significant, and is the view promulgated throughout much of recent history. In the UK, in the 1970s for example, school children were taught that until the Vikings accepted Christianity they were nasty heathens who rampaged throughout Britain. By contrast, today’s children can visit museums where Vikings are celebrated as merchants, pastoralists, and artists with a unique worldview as well as conquerors.

What are some other interpretations of Vikings? In the nineteenth century, historians in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden constructed their own Viking ages for nationalistic reasons. At that time, all three countries were in crisis. Denmark had been beaten in a war, and ceded territory to what is now Germany. Norway had become independent from Sweden in 1905, but was economically vulnerable, so Norwegians sought to create a separate identity for themselves in the past as well as the present. The Norwegian historian, Gustav Storm, was adamant it was his forebears and not the Swedes’ or Danes’ who had colonised Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland, in what is now Canada. Sweden, meanwhile, had relinquished Norway to the Norwegians and Finland to the Russians; thus, in the late nineteenth century, Sweden was keen to boost its image with rich archaeological finds to show the glory of its Viking past.

In addition to augmenting nationalism, nineteenth-century thinkers were influenced by an Englishman, Herbert Spencer, who described peoples and cultures in evolutionary terms similar to those of Charles Darwin. Spencer coined the phrase ‘survival of the fittest’, which includes the notion that, over time, there is not only technological but also moral progress. Therefore, Viking heathens’ adoption of Christianity was considered an advantageous move. These days, historians do not compare cultures in the same way, especially since, in this case, the archaeological record seems to show that heathen Vikings and Christian Europeans were equally brutal.

Views of Vikings change according not only to forces affecting historians at the time of their research, but also according to the materials they read. Since much knowledge of Vikings comes from literature composed up to 300 years after the events they chronicle, some Danish historians call these sources ‘mere legends’.

Vikings did have a written language carved on large stones, but as few of these survive today, the most reliable contemporary sources on Vikings come from writers from other cultures, like the ninth-century Persian geographer, Ibn Khordadbeh.

In the last four decades, there have been wildly varying interpretations of the Viking influence in Russia. Most non-Russian scholars believe the Vikings created a kingdom in western Russia and modern-day Ukraine led by a man called Rurik. After AD 862, Rurik’s descendants continued to rule. There is considerable evidence of this colonisation: in Sweden, carved stones, still standing, describe the conquerors’ journeys; both Russian and Ukrainian have loan words from Old Norse; and, Scandinavian first names, like Igor and Olga, are still popular. However, during the Soviet period, there was an emphasis on the Slavic origins of most Russians. (Appearing in the historical record around the sixth century AD, the Slavs are thought to have originated in Eastern Europe.) This Slavic identity was promoted to contrast with that of the neighbouring Viking Swedes, who were enemies during the Cold War.

These days, many Russians consider themselves hybrids. Indeed recent genetic studies support a Norse-colonisation theory: western Russian DNA is consistent with that of the inhabitants of a region north of Stockholm in Sweden.

The tools available to modern historians are many and varied, and their findings may seem less open to debate. There are linguistics, numismatics, dendrochronology, archaeozoology, palaeobotany, ice crystallography, climate and DNA analysis to add to the translation of runes and the raising of mighty warships. Despite these, historians remain children of their times.

Complete the notes below.

Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS OR A NUMBER for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 27-31 on your answer sheet.

Look at the following statements and the list of times and places below.

Match each statement with the correct place or time: A-H.

Write the correct letter, A-H, in boxes 32-39 on your answer sheet.

32 A geographer documents Viking culture as it happens.

33 A philosopher classifies cultures hierarchically.

34 Historians assert that Viking history is based more on legends than facts.

35 Young people learn about Viking cultural and economic activities.

36 People see themselves as unrelated to Vikings.

37 An historian claims Viking colonists to modern-day Canada came from his land.

38 Viking conquests are exaggerated to bolster the country’s ego after territorial loss.

39 DNA tests show locals are closely related to Swedes.

Which might be a suitable title for passage 3?

Choose the correct letter, A-E.

Write the correct letter in box 40 on your answer sheet.

A A brief history of Vikings

B Recent Viking discoveries

C A modern fascination with Vikings

D Interpretations of Viking history

E Viking history and nationalism

The Writing test lasts for 60 minutes.

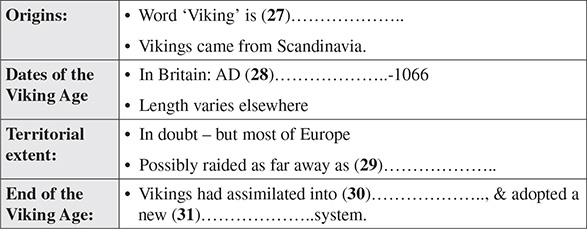

Task 1

Spend about 20 minutes on this task.

The table below shows the number of babies born to New Zealand women over time.

Write a summary of the information. Select and report the main features, and make comparisons where necessary.

Write at least 150 words.

Number of babies per 1,000 women in New Zealand

Spend about 40 minutes on this task.

Write about the following topic:

In most countries, there is an age at which people are permitted to drive but no age limit for drivers.

Some experts have proposed that drivers be aged between 20 to 70.

Why have they proposed this?

What are the drawbacks of this proposal?

Provide reasons for your answer, including relevant examples from your own knowledge or experience.

Write at least 250 words.

PART 1

How might you answer the following questions?

1 Could you tell me about the area you’re living in now?

2 Would you say it was a good place to bring up children? Why? / Why not?

3 Is there anything famous about your area?

4 Now, let’s talk about street markets. Do you ever shop at street markets?

5 What is the benefit of shopping at street markets?

6 Have you ever been to a night market? What was special about it?

7 Do you think there will be more street markets in your city in the future or fewer?

8 Let’s move on to talk about meeting people. How easy is it in your city to meet new people?

9 How do you feel about meeting people online?

10 Do you agree or disagree: it’s easier to meet people as one gets older.

PART 2

How might you speak about the following topic for two minutes?

I’d like you to tell me about a piece of equipment of yours that recently stopped working.

* What was the equipment?

* What happened to it?

* What did you do with the equipment?

And, how do you feel about the experience now?

PART 3

1 First of all, equipment in daily life.

What are some really useful pieces of equipment, and what are some that are less useful?

Do you agree or disagree: so much equipment makes people lazy?

2 Now, let’s consider inventions.

To what extent are human beings more inventive now than they were in the past?

How important are inventors to a country’s economy?

How can inventors be encouraged?

LISTENING

Section 1: 1. C; 2. B; 3. B; 4. B; 5. 12 / 12:00 / twelve; 6. Correction; 7. Saturdays (must have an ‘s’ at the end); 8. wheelchair access // a ramp (must include ‘a’); 9. Annual; 10. personal trainer. Section 2: 11. C; 12. C; 13. B; 14. C; 15. C; 16. A; 17. Public; 18. Thai; 19. external; 20. Bicycle. Section 3: 21. A; 22. 200; 23. to fly; 24. first; 25. independently; 26. fossil; 27-30. ACDG (in any order). Section 4: 31. Smaller planets; 32. (A) habitable zone; 33. (The) scientific method; 34. C; 35. C; 36. A; 37. mass; 38. 10%/ten percent/per cent; 39. insulation; 40. 500 / five hundred light-years/light years.

The highlighted text below is evidence for the answers above.

Narrator : Recording 23.

Practice Listening Test 5.

Section 1. Joining up.

You will hear a woman showing two people around a pool and gym.

Read the example.

Louise : Good evening. I’m Louise, and I’ll be showing you the complex.

Wei Wei : Nice to meet you, Louise. I’m Wei wei.

Terry : And I’m Terry.

Louise : The tour takes 20 to 30 minutes. Do you have time?

Wei Wei & Terry : Sure.

No problem.

Narrator : The answer is ‘C’.

On this occasion only, the first part of the conversation is played twice.

Before you listen again, you have 30 seconds to read questions 1 to 4.

Louise : Good evening. I’m Louise, and I’ll be showing you the complex.

Wei Wei : Nice to meet you, Louise. I’m Wei wei.

Terry : And I’m Terry.

Louise : The tour takes 20 to 30 minutes. Do you have time?

Wei Wei & Terry : Sure.

No problem.

Louise : (1) We always like to ask people who come here for the first time how they found out about us.

Wei Wei : We work on Albert Street, not far away.

Louise : So, you saw our new sign?

Terry : I must say I love the blue dolphin, but, in fact, I didn’t notice it until this evening.

Louise : Did you read about us online? We’ve had some great reviews.

Wei Wei & Terry : No, I didn’t.

I’m afraid not.

Louise : So?

Wei Wei : (1) A woman at work comes here, and she loves it.

She swims every lunchtime. I’m hoping to join her.

Louise : In winter, midday classes are popular. Or were you thinking of swimming by yourself?

Wei Wei : I’m not sure. Taking a class could be more motivating than doing laps on my own.

Louise : True.

(2) The number one reason people stop going to a pool or a gym is not the cost, nor even the time, but a lack of enthusiasm. They just run out of steam.

Terry : Speaking of steam, you’ve got a sauna here, haven’t you?

Louise : Yes, we have. It’s a great place to relax. (3) But, let’s have a look at the main pool, first.

Recently renovated, this eight-lane 25-metre pool is heated to 27° Celsius.

Wei Wei : Sounds nice.

Louise : The Children’s Pool, next door, is even warmer at 31.

Terry : Charlie might like that, Wei wei.

Louise : (4) Does your son, Charlie, swim, Terry?

Terry : Actually, Charlie’s not my son.

Louise : Oh, I’m terribly sorry.

Terry : It’s a common mistake. We’re from the same country, and we work for the same company, but we’re not a couple.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 5 to 10.

Louise : Well, I’ve shown you everything.

Terry : It certainly is impressive. I think I could easily hang out and work out here.

Louise : So, let’s talk about membership.

Wei Wei : I think I’ll start with a Weekly Membership. I’m all too conscious of my limitations, and you’re right about people giving up. I’ve done that before!

I’d like to sign up for the Water Polo class, between (5) twelve and one, and for the Stroke (6) Correction class.

Louise : I teach Stroke (6) Correction on (7) Saturdays. You may find it’s a struggle at first, but within a few lessons, your speed will really increase. Most swimmers have no idea that the way they use their arms affects their performance.

Wei Wei : Do you also work on swimmers’ legs? Mine are very weak.

Louise : That’s for another class, called Kick Correction. What about classes for Charlie?

Wei Wei : Charlie’s in a wheelchair at the moment. He’s just had an operation. I see you’ve got (8) wheelchair access through the parking lot and (8) a ramp into the Children’s Pool. He’ll need both of those. Maybe once Charlie’s comfortable in the water, we’ll think about classes.

Louise : I do hope so.

What about you, Terry?

Terry I think I’ll go for an (9) Annual Membership. I’m moving into an apartment just two blocks away this weekend. First up, I’d like to take the Monday-night Weight Training class in the gym. And, I noticed your offer of a (10) personal trainer for a one-month trial. Once my (10) personal trainer has developed a programme for me, I’m sure I’ll take some more classes.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 1.

Narrator : Recording 24.

Section 2. Wharf redevelopment.

You will hear a man talking about plans to redevelop a wharf.

Before you listen, you have 30 seconds to read questions 11 to 16.

Speaker : Good afternoon, ladies and gentleman. Thanks for coming to this forum about the redevelopment of Queen’s Wharf. I hope you’ve got some tea or coffee, and you’ve put your phones on silent.

Right. Essentially, we’re now dealing with the final phase of the project. If you’ve looked at the plans, you’ll’ve noticed that a couple of changes have been made to the previous ones – the most noticeable being the removal of accommodation. You may recall that the original developer went bankrupt; when Cato and Brown took the project over, they scaled things down. As a result, there are no apartments on the second floor of the wharf – in fact, (11) there won’t be a second floor at all. I’m sure a fair few of you will applaud this decision since you thought you’d lose your harbour views.

(12) What else has been scrapped? Oh yes, the fourth jetty for water taxis. It seems the contract with Fletcher’s Taxis has been amended so vessels can dock at any of the three jetties as long as no ferry is within five minutes of arrival.

(13) Depending on your feedback, there are some other features of the plan that Cato and Brown may yet dispense with. For instance, the canopy extension was highly controversial in the first consultation; and, since the canopy doesn’t go on until the very end, (13) its size is yet to be determined. It has to cover the existing structure, but whether it goes out over the bus shelter is another matter. (14) The length of the bus shelter has also been reviewed. As many members of the public pointed out, there are only two buses that connect to this wharf, so (14) a long shelter isn’t necessary. Years ago, there was no shelter at all; people used to wait inside the wharf building. However, the owners of the commercial space complained: bus passengers rarely bought anything more than a newspaper or a chocolate bar, and there were instances of shoplifting. The owners also got tired of children who rode their bicycles and skateboards up and down the corridor, even though it was forbidden, (15) so this is one reason why the corridor is absent from the latest plan.

Let’s move on to (16) what’s set in stone, so to speak – (16) things that the council insists upon. Cato and Brown are adding a third jetty for the new ferry service to Green Island. With a permanent community on the island, it’s profitable to run a ferry. The council hopes the wharf will generate much of its own income, so this third jetty is not up for discussion. Likewise, (16) renovation has to be done to parts of the wharf that no longer meet safety standards, like the weathered or rotten posts and planks; and, the wooden eastern walkway will be almost entirely replaced.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the talk, you have 30 seconds to read questions 17 to 20.

Now I’d like to spend a few minutes outlining the redesign of the space inside the wharf building.

Firstly, public comment was made during the initial planning phase, so the only input we’re asking for now relates to the (17) public space where there used to be a bookshop and a food outlet. Probably toilets will go there, along with seats, vending machines, plants, and sculptures. We’re hoping local artists will submit ideas for artworks, and that the plants will be native.

As you can see from the plan, the size of the internal space remains the same, but the corridor will be subsumed into the floor space of the (17) public area and the (18) Thai restaurant in Shop 4. Access to the shops will be (19) external only, via the eastern and western walkways. I think the (20) bicycle shop, next to the café, made a submission against (19) external access, (15) requesting the corridor be retained, but this was rejected.

OK. Let’s have another drink while we discuss parking at the wharf…

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 2.

Narrator : Recording 25.

Section 3. Post-graduate research.

You will hear two students talking about their post-graduate research.

Before you listen, you have 30 seconds to read questions 21 to 25.

Vanessa : Hey, Marcus, how are you?

Marcus : I’m really well.

Vanessa : I thought you were in South Africa.

Marcus : I was until a month ago. I came back to do a PhD.

Vanessa : D’you know what you’re getting into? I’m writing a Master’s thesis, and it’s driving me crazy.

Marcus : Oh dear.

Vanessa : I heard you had an amazing job in a national park. Why would you give that up?

Marcus : (21) It’s true, I started out working in a national park, looking after ostriches, and it did seem like my dream job. But, almost by accident, I got involved in taking DNA samples from the birds. I ended up analysing the samples, myself, in a lab in Cape Town.

(21) It was incredible – working in the lab. Suddenly, I realised I had greater ambitions than being a park ranger.

Vanessa : Well, well.

What was the DNA for?

Marcus : You see, ostriches are part of a group of flightless birds called ratites, and there’s a mystery in ornithology about how they spread around the globe when they can’t fly.

Vanessa : That is weird.

Marcus : There’s one hypothesis that they originated in Gondwanaland – a supercontinent that moved apart from Pangaea between (22) 200 and 120 million years ago.

Vanessa : Didn’t Gondwanaland separate into Australia, Africa, and South America?

Marcus : That’s right. Plus Antarctica and India.

The theory is that ratites stayed on the drifting landmasses, which would account for their present distribution. In the opposing hypothesis, borne out in the (26) fossil record, ratites originated in the northern supercontinent, called Laurasia. Then, they flew south, but lost the ability (23) to fly around 50 million years ago.

Vanessa : Which theory do you favour?

Marcus : I’m keen on the Gondwanaland one because DNA analysis shows ostriches are the oldest of the ratites, and, according to geologists, Africa broke away from Gondwanaland (24) first. Also, DNA analysis of the extinct elephant bird of Madagascar and the kiwi of New Zealand suggests they’re close relatives, so it’s unlikely they became flightless (25) independently.

Vanessa : But isn’t the (26) fossil record more reliable?

Marcus : Not really. It’s open to interpretation.

Narrator : Before you listen to the rest of the conversation, you have 30 seconds to read questions 27 to 30.

Marcus : How’s your research going?

Vanessa : Not so well, I’m afraid.

Marcus : I presume you’re doing a Master’s in Public Health.

(27-30) What’s the topic of your thesis?

Vanessa : Well, that was my first problem. It’s changed about 20 times. Currently, I’m looking at fathers’ visiting habits in neonatal wards.

Marcus : Remind me how old neonatal babies are.

Vanessa : Up to four weeks.

Marcus : And what’s the aim of your research?

Vanessa : I’d like to propose a change to hospital policy. I think limited access by fathers to their newborns would improve the health of infants and their mothers, especially in intensive care.

Marcus : Whoa! That’s a radical idea. Letting the family be part of the birth process has been standard practice in hospitals for 40 years.

Vanessa : And because of that I chose a quantitative research methodology.

Marcus : You’ll have to tell me what that is again as well.

Vanessa : Quantitative research collects data that can be explained numerically. It’s used to determine general trends.

Marcus : Uh huh.

Vanessa : (27-30) But, my next obstacle was that I couldn’t get a large enough sample of paternal behaviour to analyse it quantitatively.

Marcus : Why not?

Vanessa : (27-30) Four of the hospitals I approached refused me access to their patients. I did get permission from two others, where I used to work, but the results of my survey were so scattered I couldn’t model anything.

Marcus : So, what did you do?

Vanessa : I opted for a qualitative approach. I gave up large data collection, and did in-depth interviews with a handful of fathers. At the same time, (27-30) I set up an online discussion group for fathers.

Marcus : How did that go?

Vanessa : (27-30) Frankly, it was too slow to be useful. I’ve got to finish my thesis by the end of the year, and (27-30) managing the website took too much time.

Marcus : Have you considered regression analysis? That is, determining the strength of the relationship between variables. It’s used for things like trying to prove that video games lead to more violence among young viewers.

Vanessa : Yes, I have. In fact, I’ve changed supervisors, and my new one has guided me towards regression analysis, so at last I’m making progress.

Narrator : You now have 30 seconds to check your answers.

That is the end of Section 3.

Narrator : Recording 26. Section 4. Earth’s cousin. You will hear a lecture on searching for planets similar to Earth. Before you listen, you have 45 seconds to read questions 31 to 40.

Lecturer : For hundreds of years, people have wondered whether other planets could sustain human life. Twentieth-century space missions cast doubt over colonisation of our own solar system, but there’s plenty of hope beyond.

Distant bodies orbiting far-away stars are known as exoplanets. Since 1996, thousands of exoplanets have been found, most of which are massive hot balls of gas, like Jupiter. However, a new US mission is focusing on (31) smaller planets, one half to twice the size of Earth. These must also be close enough to their star to be in a (32) habitable zone.

Today, I’d like to discuss NASA’s Kepler Mission, which began in 2009 and is ongoing.

But first, who was Kepler? Well, Johannes Kepler lived from 1571 to 1630 mostly in what is now Germany. He was a physicist, astronomer, and optician. He was the first person to explain planetary motion correctly, and, more importantly, he developed a way of working in which he sought to prove that theories must be universal, verifiable, and precise. This is known as (33) the scientific method.

I do think it is fitting that a tiny spacecraft is named after a giant of astronomy.

NASA’s Kepler satellite is small and relatively simple. Other telescopes, like Hubble, provide exciting data, (34) but Kepler surveys just one area of the galaxy – the constellations Cygnus and Lyrae – and records events over several years. It has already identified around 1,000 new planets, and provided data on another 3,000 potential planets.

Kepler is powered by a solar array. Its largest instrument is a photometer – (35) a sensor that measures the light emitted by more than 100,000 stars. The photometer is so sensitive it can detect a drop in brightness when a planet moves, or transits, in front of a star, of one part in 10,000. This is like recording the decreased brightness of a car headlight when a small insect flies across it.

When a planet transits, NASA’s computers graph the curving light from the star. Regular, repeated dips in the curve could indicate a new planet. A smaller dip, (36) when a planet passes behind its star, creates reflections. Scientists can draw conclusions about the planet’s atmosphere from these reflections, because, as Kepler knew, the laws of physics and chemistry are universal – even way out in space. For example, light is absorbed by different atoms at different wavelengths, so a light signature provides data on a planet’s atmosphere. Hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, sodium, and other elements have been identified in new planets. However, the proportion of their composition is uncertain, making the detection of water difficult.

But back to the Kepler data, and some recent candidates for human habitation.

In 2013, a star named Kepler 62 was found with two planets in its (32) habitable zone. At first, these were considered similar to Earth, but on further analysis, each planet’s (37) mass was found to be several times greater than that of Earth. Their gravity might be strong enough to pull in helium and hydrogen gas, but this makes them similar to Neptune rather than Earth.

The following year, a star called Kepler 186 came under scrutiny. Its fifth planet, known as Kepler 186f, seemed a more likely candidate. With a diameter of 14,000 kilometres, it is roughly (38) ten percent wider than Earth. It orbits close enough to Kepler 186 for it to be temperate, allowing water to flow at the surface.

Smaller than the planets orbiting Kepler 62, Kepler 186f is more likely to have similar gravity to Earth’s and a rocky surface, perhaps containing iron, ice, and liquid water. At the outer edge of the habitable zone, its surface may freeze, as it receives one sixth of the light from its star that Earth does from the Sun. On the other hand, with a greater mass, Kepler 186f may have a thicker atmosphere, providing sufficient (39) insulation. This has led astronomers to dub Kepler 186f ‘Earth’s cousin’, not its twin.

But I can hear you thinking, OK, there are planets out there that sound Earth-like, but can we reach them? Currently: No. In the near to medium-term future? Afraid not.

The only known man-made object to have left the solar system is the unmanned Voyager 1 probe. This happened in late 2013, and it had taken 37 years to travel from Earth. Voyager travels at around 61,000 kilometers per hour. Kepler 186f is about (40) 500 light years away. At Voyager’s current speed, it’d take 17,400 years to travel a single light year, or 8.7 million years for the journey from Earth to Kepler 186f. The Space Shuttle, the only speedy manned spacecraft, is far slower than Voyager, with speeds of just 45,000 kilometres per hour, meaning a twelve-million-year journey!

Meantime, the Hubble Telescope is investigating a suitable planet called GJ124b, at a distance of 40 light years away. But whether a planet is 40 or (40) 500 light years away is immaterial.

Humans have always reached for the stars. Kepler the man, and Kepler the spacecraft have raised the possibility of human habitation; only our transport remains primitive.

Narrator : That is the end of the Listening test.

You now have ten minutes to transfer your answers to your answer sheet.

READING: Passage 1: 1. F/False; 2. NG/Not Given; 3. NG/Not Given; 4. F/False; 5. T/True; 6. thin; 7. stem; 8. crop (‘yield’ is incorrect as it does not appear in the singular in the passage); 9. 4/four; 10. 5/five million; 11. morning; 12. C; 13. B. Passage 2: 14. E; 15. A; 16. F; 17. D; 18. E; 19. B; 20. B; 21. A; 22. D; 23. The brain; 24. 34,000/Thirty-four thousand; 25. The human body // Human beings; 26. Respect and excitement // Excitement and respect. Passage 3: 27. obscure; 28. 793; 29. Northwest Africa; 30. local populations; 31. religious; 32. F; 33. D; 34. E; 35. A; 36. G; 37. B; 38. C; 39. H; 40. D.

The highlighted text below is evidence for the answers above.

If there is a question where ‘Not given’ is the answer, no evidence can be found, so there is no highlighted text.

Rice is a tall grass with a drooping panicle that contains numerous edible grains, and has been cultivated in China for more than 6,000 years. A staple throughout Asia and large parts of Africa, it is now (1) grown in flooded paddy fields from sea level to high mountains and harvested three times a year. According to the Food and Health Organisation of the United Nations, around four billion people currently receive a fifth of their calories from rice.

Recently, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have slightly reduced rice consumption due to the adoption of more western diets, but almost all other countries have raised their consumption due to population increase. Yet, since 1984, there have been diminishing rice yields around the world.

From the 1950s to the early 1960s, rice production was also suffering: India was on the brink of famine, and China was already experiencing one. In the late 1950s, (4) Norman Borlaug, an American plant pathologist, began advising Punjab State in northwestern India to grow a new semi-dwarf variety of wheat. This was so successful that, in 1962, a semi-dwarf variety of rice, called IR8, developed by the Philippine International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), was planted throughout Southeast Asia and India. This semi-dwarf variety heralded (5) the Green Revolution, which saved the lives of millions of people by almost doubling rice yields: from 1.9 metric tons per hectare in 1950-64, to 3.5 metric tons in 1985-98.

IR8 survived because, as a semi-dwarf, it only grows to a moderate height, and it does not (6) thin out, keel over, and drown like traditional varieties. Furthermore, its short thick (7) stem is able to absorb chemical fertilisers, but, as stem growth is limited, the plant expends energy on producing a large panicle of heavy seeds, ensuring a greater (8) crop.

However, even with a massive increase in rice production, semi-dwarf varieties managed to keep up with population growth for only ten years. In Africa, where rice consumption is rising by 20% annually, and where one third of the population now depends on the cereal, this is disturbing. At the current rate, within the next 20 years, rice will surpass maize as the major source of calories on that continent. Meantime, even in ideal circumstances, paddies worldwide are not producing what they once did, for reasons largely unknown to science. An average 0.8% fall in yields has been noted in rich rice-growing regions; in less ideal ones, flood, drought and salinity have meant yields have fallen drastically, sometimes up to 40%.

The sequencing of the rice genome took place in 2005, after which the IRRI developed genetically modified flood-resistant varieties of rice, called Sub 1, which produce up to (9) four times the amount of edible grain from non-modified strains. In 2010, a handful of farmers worldwide were planting IRRI Sub 1 rice; now, over (10) five million are doing so. Currently, drought- and salt-resistent varieties are being trialled since most rice is grown in the great river basins of the Brahmaputra, the Irawaddy, and the Mekong that are all drying up or becoming far saltier.

With global warming, many rice-growing regions are hotter than 20 years ago. Nearly all varieties of rice, including IR8, flower in the afternoon, but the anthers – little sacs that contain male pollen – wither and die in soaring temperatures. IRRI scientists have identified one variety of rice, known as Odisha, that flowers in the early (11) morning, and they are in the process of genetically modifying IR8 so it contains Odisha-flowering genes, although it may be some time before this is released.

While there is a clear need for more rice, many states and countries seem less keen to influence agricultural policy directly than they were in the past. Some believe rice demand will dip in wealthier places, as occurred in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan; (12) others consider it more prudent to devote resources to tackling obesity or to limiting intensive farming that is environmentally destructive.

Some experts say where there is state intervention it should take the form of reducing subsidies to rice farmers to stimulate production; others propose that small land holdings should be consolidated into more economically viable ones. There is no denying that land reform is pressing, but many governments shy away from it, fearing losses at the ballot box, all the while knowing that rural populations are heading for the city in droves anyway. (13) And, as they do so, cities expand, eating up fertile land for food production.

One can only hope that the IRRI and other research institutions will spearhead half a dozen mini green revolutions, independently of uncommitted states.

A new perspective on bacteria

A Microbes are organisms too small to be seen by the naked eye, including bacteria, blue-green algae, yeasts, fungi, viruses, and viroids.

(15) A large, diverse group, almost all bacteria are between one and ten µ3 (larger ones reach 0.5 mm). (19) Generally single-celled, with a distinctive cellular structure lacking a true nucleus, most bacterial genetic information is carried on a DNA loop in the cytoplasm4 with the membrane possessing some nuclear properties.

(15) There are three main kinds of bacteria – spherical, (20) rod-like, and spiral – known by their Latin names of coccus, (20) bacillus, and spirillum. Bacteria occur alone, in pairs, clusters, chains, or more complex configurations. Some live where oxygen is present; others, where it is absent.

The relationship between bacteria and their hosts is symbiotic, benefitting both organisms, or the hosts may be destroyed by parasitic or disease-causing bacteria.

B In general, humans view bacteria suspiciously, yet it is now thought they partly owe their existence to microbes living long, long ago.

During photosynthesis, plants produce oxygen that humans need to fuel blood cells. Most geologists believe the early atmosphere on (21) Earth contained very little oxygen until around 2½ billion years ago, when microbes bloomed. Ancestral forms of cyanobacteria, for example, evolved into chloroplasts – the cells that carry out photosynthesis. Once plants inhabited the oceans, oxygen levels rose dramatically, so complex life forms could eventually be sustained.

The air humans breathe today is oxygen-rich, and the majority of airborne microbes are harmless, but the air does contain industrial pollutants, allergens, and infectious microbes or pathogens that cause illness.

C The fact is that scientists barely understand microbes. Bacteria have been proven to exist only in the past 350 years; viruses were discovered just over 100 years ago, but in the past three decades, the ubiquity of microbes has been established with bacteria found kilometres below the Earth’s crust and in the upper atmosphere. Surprisingly, they survive in dry deserts and the frozen reaches of Antarctica; they dwell in rain and snow clouds, as well as inside every living creature.

Air samples taken in 2006 from two cities in Texas contained at least 1,800 distinct species of bacteria, making the air as rich as the soil. These species originated both in Texas and as far away as western China. (22) It now seems that the number of microbe species far exceeds the number of stars.

D (17) Inside every human being there are trillions of bacteria with their weight estimated at 1.36 kg in an average adult, or about as heavy as (23) the brain. Although tiny, 90% of cells in a human are bacterial. With around eight million genes, these bacteria outnumber genes in human cells by 300 times.

The large intestine contains the most bacteria – almost (24) 34,000 species – but the crook of the elbow harbours over 2,000 species. Many bacteria are helpful: digesting food; aiding the immune system; creating moisturiser; and, manufacturing vitamins. Some have highly specialised functions, like Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, which breaks down plant starch, so an infant can make the transition from mother’s milk to a more varied diet.

Undeniably, some bacteria are life-threatening. One, known as golden staph, Staphylococcus aureus, plagues hospitals, where it infects instruments and devours human tissue until patients die from toxic shock. Worse, it is still resistant to antibiotics.

E Antibiotics themselves are bacteria. (14) In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered that a mould in his laboratory produced a chemical he named penicillin. In 1951, William Bouw collected soil from the jungles of Borneo that eventually became vancomycin. Pharmaceutical companies still hunt for beneficial bacteria, but (18) Michael Fischbach from University of California believes that (25) the human body itself is a ready supply.

F Scientific ignorance about bacteria is largely due to an inability to cultivate many of them in a laboratory, but recent DNA sequencing has meant populations can be analysed by computer program without having to grow them.

Fischbach and his team have created and trained a computer program to identify gene clusters in microbial DNA sequences that might produce useful molecules. Having collected microbial DNA from 242 healthy human volunteers, the scientists sequenced the genomes of 2,340 different species of microbes, most of which were completely new discoveries.

In searching the gene clusters, (16) Fischbach et al found 3,118 common ones that could be used in pharmaceuticals, for example, a gene cluster from the bacterium Lactobacillus gasseri, successfully reared in the lab, produced a molecule they named lactocillin. Later, they discovered the structure of this was very similar to an antibiotic, LFF571, undergoing clinical trials by a major pharmaceutical company. To date, lactocillin has killed harmful bacteria, so it may also be a reliable antibiotic.

G Naturally, the path to patenting medicine is strewn with failures, but, since bacteria have been living inside humans for millions of years, they are probably safe to reintroduce in new combinations and in large amounts.

Undoubtedly, the fight against pathogens, like golden staph, must continue, but as scientists learn more about microbes, (26) respect and excitement for them grows, and their positive applications become ever more probable.

In the last century, Vikings have been perceived in numerous different ways – vilified as conquerors and romanticised as adventurers. How Vikings have been employed in nation-building is a topic of some interest.

In English, Vikings are also known as Norse or Norsemen. Their language greatly influenced English, with the nouns, ‘Hell’, ‘husband’, ‘law’, and ‘window’, and the verbs, ‘blunder’, ‘snub’, ‘take’, and ‘want’, all coming from Old Norse. However, the origins of the word ‘Viking’, itself, are (27) obscure: it may mean ‘a Scandinavian pirate’, or it may refer to ‘an inlet’, or a place called Vik, in modern-day Norway, from where the pirates came. These various names – Vikings, Norse, or Norsemen, and doubts about the very word ‘Viking’ suggest historical confusion.

Loosely speaking, the Viking Age endured from the late eighth to the mid-eleventh centuries. Vikings sailed to England in (28) AD 793 to storm coastal monasteries, and subsequently large swathes of England fell under Viking rule – indeed several Viking kings sat on the English throne. It is generally agreed that the Battle of Hastings, in 1066, when the Norman French invaded, marks the end of the English Viking Age, but the Irish Viking age ended earlier, while Viking colonies in Iceland and Greenland did not dissolve until around AD 1500.

How much territory Vikings controlled is also in dispute – Scandinavia and Western Europe certainly, but their reach east and south is uncertain. They plundered and settled down the Volga and Dnieper rivers, and traded with modern-day Istanbul, but the archaeological record has yet to verify that Vikings raided as far away as (29) Northwest Africa, as some writers claim.

The issue of control and extent is complex because many Vikings did not return to Scandinavia after raiding but assimilated into (30) local populations, often becoming Christian. To some degree, the Viking Age is defined by religion. Initially, Vikings were polytheists, believing in many gods, but by the end of the age, they had permanently accepted a new monotheistic (31) religious system – Christianity.

This transition from so-called pagan plunderers to civilised Christians is significant, and is the view promulgated throughout much of recent history. In the UK, in the 1970s for example, school children were taught that until the Vikings accepted Christianity they were nasty heathens who rampaged throughout Britain. (35) By contrast, today’s children can visit museums where Vikings are celebrated as merchants, pastoralists, and artists with a unique worldview as well as conquerors.

What are some other interpretations of Vikings? In the nineteenth century, historians in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden constructed their own Viking ages for nationalistic reasons. At that time, all three countries were in crisis. Denmark had been beaten in a war, and ceded territory to what is now Germany. Norway had become independent from Sweden in 1905, but was economically vulnerable, so Norwegians sought to create a separate identity for themselves in the past as well as the present, (37) thus the Norwegian historian, Gustav Storm, was adamant it was his forebears and not the Swedes’ or Danes’ who had colonised Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland, in what is now Canada. (38) Sweden, meanwhile, had relinquished Norway to the Norwegians and Finland to the Russians; thus, in the late nineteenth century, Sweden was keen to boost its image with rich archaeological finds to show the glory of its Viking past.

In addition to augmenting nationalism, (33) nineteenth-century thinkers were influenced by an Englishman, Herbert Spencer, who described peoples and cultures in evolutionary terms similar to those of Charles Darwin. Spencer coined the phrase ‘survival of the fittest’, which includes the notion that, over time, there is not only technological but also moral progress. Therefore, Viking heathens’ adoption of Christianity was considered an advantageous move. These days, historians do not compare cultures in the same way, especially since, in this case, the archaeological record seems to show that heathen Vikings and Christian Europeans were equally brutal.

Views of Vikings change according not only to forces affecting historians at the time of their research, but also according to the materials they read. (34) Since much knowledge of Vikings comes from literature composed up to 300 years after the events they chronicle, some Danish historians call these sources ‘mere legends’.

Vikings did have a written language carved on large stones, but as few of these survive today, (32) the most reliable contemporary sources on Vikings come from writers from other cultures, like the ninth-century Persian geographer, Ibn Khordadbeh.

In the last four decades, there have been wildly varying interpretations of the Viking influence in Russia. Most non-Russian scholars believe the Vikings created a kingdom in western Russia and modern-day Ukraine led by a man called Rurik. After AD 862, Rurik’s descendants continued to rule. There is considerable evidence of this colonisation: in Sweden, carved stones, still standing, describe the conquerors’ journeys; both Russian and Ukrainian have loan words from Old Norse; and, Scandinavian first names, like Igor and Olga, are still popular. (36) However, during the Soviet period, there was an emphasis on the Slavic origins of most Russians. (Appearing in the historical record around the sixth century AD, the Slavs are thought to have originated in Eastern Europe.) This Slavic identity was promoted to contrast with that of the neighbouring Viking Swedes, who were enemies during the Cold War.

These days, many Russians consider themselves hybrids. (39) Indeed recent genetic studies support a Norse-colonisation theory: western Russian DNA is consistent with that of the inhabitants of a region north of Stockholm in Sweden.

(40) The tools available to modern historians are many and varied, and their findings may seem less open to debate. There are linguistics, numismatics, dendrochronology, archaeozoology, palaeobotany, ice crystallography, climate and DNA analysis to add to the translation of runes and the raising of mighty warships. Despite these, historians remain children of their times.

1A micron = 10-6 m

2Material inside a cell

3A micron = 10-6 m

4Material inside a cell