THE HISTORICAL CONES1

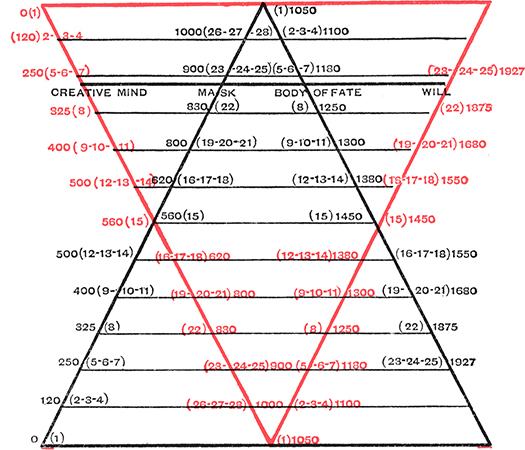

The numbers in brackets refer to phases, and the other numbers to dates A.D. The line cutting the cones a little below 250, 900, 1180 and 1927 shows four historical Faculties related to the present moment. May 1925.

I

LEDA2

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.

How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs,

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And Agamemnon dead.3

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air,

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

II

Stray Thoughts

One must bear in mind that the Christian Era, like the two thousand years, let us say, that went before it, is an entire wheel, and each half of it an entire wheel, that each half when it comes to its 28th Phase reaches the 15th Phase or the 1st Phase of the entire era. It follows therefore that the 15th Phase of each millennium, to keep the symbolic measure of time, is Phase 8 or Phase 22 of the entire era, that Aphrodite rises from a stormy sea, that Helen could not be Helen but for beleaguered Troy.4 The era itself is but half of a greater era and its Phase 15 comes also at a period of war or trouble. The greater number is always more primary than the lesser and precisely because it contains it. A millennium is the symbolic measure of a being that attains its flexible maturity and then sinks into rigid age.

A civilisation is a struggle to keep self-control, and in this it is like some great tragic person, some Niobe who must display an almost superhuman will or the cry will not touch our sympathy.5 The loss of control over thought comes towards the end; first a sinking in upon the moral being, then the last surrender, the irrational cry, revelation—the scream of Juno’s peacock.6

III

2000 B.C. to A.D. 17

I imagine the annunciation that founded Greece as made to Leda, remembering that they showed in a Spartan temple, strung up to the roof as a holy relic, an unhatched egg of hers; and that from one of her eggs came Love and from the other War.8 But all things are from antithesis, and when in my ignorance I try to imagine what older civilisation that annunciation rejected I can but see bird and woman blotting out some corner of the Babylonian mathematical starlight.I

Was it because the older civilisation like the Jewish thought a long life a proof of Heavenly favour that the Greek races thought those whom the Gods love must die young, hurling upon some age of crowded comedy their tragic sense?10 Certainly their tribes, after a first multitudinous revelation—dominated each by its Daimon and oracle-driven—broke up a great Empire and established in its stead an intellectual anarchy.11 At some 1000 years before Christ I imagine their religious system complete and they themselves grown barbaric and Asiatic.12 Then came Homer, civil life, a desire for civil order dependent doubtless on some oracle, and then (Phase 10 of the new millennium) for independent civil life and thought. At, let me say, the sixth century B.C. (Phase 12) personality begins, but there is as yet no intellectual solitude. A man may rule his tribe or town but he cannot separate himself from the general mass. With the first discovery of solitude (Phases 13 and 14) comes, as I think, the visible art that interests us most to-day, for Phidian art, like the art of Raphael, has for the moment exhausted our attention.13 I recall a Nike at the Ashmolean Museum with a natural unsystematised beauty like that before Raphael, and above all certain pots with strange half-supernatural horses dark on a light ground.14 Self-realisation attained will bring desire of power—systematisation for its instrument—but as yet clarity, meaning, elegance, all things separated from one another in luminous space, seem to exceed all other virtues. One compares this art with the thought of Greek philosophers before Anaxagoras, where one discovers the same phases, always more concerned with the truth than with its moral or political effects. One longs for the lost dramatists, the plays that were enacted before Aeschylus and Sophocles arose, both Phidian men.15

But one must consider not the movement only from the beginning to the end of the ascending cone, but the gyres that touch its sides, the horizontal dance.16

Hands gripped in hands, toes close together,

Hair spread on the wind they made;

That lady and that golden king

Could like a brace of blackbirds sing.17

Side by side with Ionic elegance there comes after the Persian wars a Doric vigour, and the light-limbed dandy of the potters, the Parisian-looking young woman of the sculptors, her hair elaborately curled, give place to the athlete.18 One suspects a deliberate turning away from all that is Eastern, or a moral propaganda like that which turned the poets out of Plato’s Republic, and yet it may be that the preparation for the final systematisation had for its apparent cause the destruction, let us say, of Ionic studios by the Persian invaders, and that all came from the resistance of the Body of Fate to the growing solitude of the soul.19 Then in Phidias Ionic and Doric influence unite—one remembers Titian—and all is transformed by the full moon, and all abounds and flows.20 With Callimachus pure Ionic revives again, as Furtwängler has proved, and upon the only example of his work known to us, a marble chair, a Persian is represented, and may one not discover a Persian symbol in that bronze lamp, shaped like a palm, known to us by a description in Pausanias?21 But he was an archaistic workman, and those who set him to work brought back public life to an older form.22 One may see in masters and man a momentary dip into ebbing Asia.

Each age unwinds the thread another age had wound, and it amuses one to remember that before Phidias, and his westward-moving art, Persia fell, and that when full moon came round again, amid eastward-moving thought, and brought Byzantine glory, Rome fell; and that at the outset of our westward-moving Renaissance Byzantium fell; all things dying each other’s life, living each other’s death.23

After Phidias the life of Greece, which being antithetical had moved slowly and richly through the antithetical phases, comes rapidly to an end. Some Greek or Roman writer whose name I forget will soon speak of the declining comeliness of the people, and in the arts all is systematised more and more, and the antagonist recedes.24 Aristophanes’ passion-clouded eye falls before what one must believe, from Roman stage copies, an idler glance.25 (Phases 19, 20, 21.) Aristotle and Plato end creative system—to die into the truth is still to die—and formula begins.26 Yet even the truth into which Plato dies is a form of death, for when he separates the Eternal Ideas from Nature and shows them self-sustained he prepares the Christian desert and the Stoic suicide.27

I identify the conquest of Alexander and the break-up of his kingdom, when Greek civilisation, formalised and codified, loses itself in Asia, with the beginning and end of the 22nd Phase, and his intention recorded by some historian to turn his arms westward shows that he is but a part of the impulse that creates Hellenised Rome and Asia.28 There are everywhere statues where every muscle has been measured, every position debated, and these statues represent man with nothing more to achieve, physical man finished and complacent, the women slightly tinted, but the men, it may be, who exercise naked in the open air, the colour of mahogany. Every discovery after the epoch of victory and defeat (Phase 22) which substitutes mechanics for power is an elimination of intellect by delight in technical skill (Phase 23), by a sense of the past (Phase 24), by some dominant belief (Phase 25). After Plato and Aristotle, the mind is as exhausted as were the armies of Alexander at his death, but the Stoics can discover morals and turn philosophy into a rule of life. Among them doubtless—the first beneficiaries of Plato’s hatred of imitation—we may discover the first benefactors of our modern individuality, sincerity of the trivial face, the mask torn away. Then, a Greece that Rome has conquered, and a Rome conquered by Greece, must, in the last three phases of the wheel, adore, desire being dead, physical or spiritual force.29

This adoration which begins in the second century before Christ creates a world-wide religious movement as the world was then known, which, being swallowed up in what came after, has left no adequate record. One knows not into how great extravagance Asia, accustomed to abase itself, may have carried what soon sent Greeks and Romans to stand naked in a Mithraic pit, moving their bodies as under a shower-bath that those bodies might receive the blood of the bull even to the last drop.30 The adored image took everywhere the only form possible as the antithetical age died into its last violence—a human or animal form. Even before Plato that collective image of man dear to Stoic and Epicurean alike, the moral double of bronze or marble athlete, had been invoked by Anaxagoras when he declared that thought and not the warring opposites created the world.31 At that sentence the heroic life, passionate fragmentary man, all that had been imagined by great poets and sculptors began to pass away, and instead of seeking noble antagonists, imagination moved towards divine man and the ridiculous devil. Now must sages lure men away from the arms of women because in those arms man becomes a fragment; and all is ready for revelation.

When revelation comes athlete and sage are merged; the earliest sculptured image of Christ is copied from that of the Apotheosis of Alexander the Great;32 the tradition is founded which declares even to our own day that Christ alone was exactly six feet high, perfect physical man.33 Yet as perfect physical man He must die, for only so can primary power reach antithetical mankind shut within the circle of its senses, touching outward things alone in that which seems most personal and physical. When I think of the moment before revelation I think of Salome—she, too, delicately tinted or maybe mahogany dark—dancing before Herod and receiving the Prophet’s head in her indifferent hands, and wonder if what seems to us decadence was not in reality the exaltation of the muscular flesh and of civilisation perfectly achieved.34 Seeking images, I see her anoint her bare limbs according to a medical prescription of that time, with lion’s fat, for lack of the sun’s ray, that she may gain the favour of a king, and remember that the same impulse will create the Galilean revelation and deify Roman Emperors whose sculptured heads will be surrounded by the solar disk.35 Upon the throne and upon the cross alike the myth becomes a biography.36

IV

A.D. 1 to A.D. 105037

God is now conceived of as something outside man and man’s handiwork, and it follows that it must be idolatry to worship that which Phidias and Scopas made, and seeing that He is a Father in Heaven, that Heaven will be found presently in the Thebaid, where the world is changed into a featureless dust and can be run through the fingers;38 and these things are testified to from books that are outside human genius, being miraculous, and by a miraculous Church, and this Church, as the gyre sweeps wider, will make man also featureless as clay or dust. Night will fall upon man’s wisdom now that man has been taught that he is nothing.39 He had discovered, or half-discovered, that the world is round and one of many like it,40 but now he must believe that the sky is but a tent spread above a level floor, and that he may be stirred into a frenzy of anxiety and so to moral transformation, blot out the knowledge or half-knowledge that he has lived many times, and think that all eternity depends upon a moment’s decision. Heaven itself, transformation finished, must appear so vague and motionless that it seems but a concession to human weakness.41 It is even essential to this faith to declare that God’s messengers, those beings who show His will in dreams or announce it in visionary speech, were never men. The Greeks thought them great men of the past, but now that concession to mankind is forbidden.42 All must be narrowed into the sun’s image cast out of a burning-glass and man be ignorant of all but the image.

The mind that brought the change, if considered as man only, is a climax of whatever Greek and Roman thought was most a contradiction to its age; but considered as more than man He controlled what Neo-Pythagorean and Stoic could not—irrational force. He could announce the new age, all that had not been thought of, or touched, or seen, because He could substitute for reason, miracle.

We say of Him because His sacrifice was voluntary that He was love itself, and yet that part of Him which made Christendom was not love but pity, and not pity for intellectual despair, though the man in Him, being antithetical like His age, knew it in the Garden, but primary pity, that for the common lot, man’s death, seeing that He raised Lazarus, sickness, seeing that He healed many, sin, seeing that He died.43

Love is created and preserved by intellectual analysis, for we love only that which is unique, and it belongs to contemplation, not to action, for we would not change that which we love. A lover will admit a greater beauty than that of his mistress but not its like, and surrenders his days to a delighted laborious study of all her ways and looks, and he pities only if something threatens that which has never been before and can never be again. Fragment delights in fragment and seeks possession, not service; whereas the Good Samaritan discovers himself in the likeness of another, covered with sores and abandoned by thieves upon the roadside, and in that other serves himself.44 The opposites are gone; he does not need his Lazarus; they do not each die the other’s life, live the other’s death.

It is impossible to do more than select an arbitrary general date for the beginning of Roman decay (Phases 2 to 7, A.D. 1 to A.D. 250).45 Roman sculpture—sculpture made under Roman influence whatever the sculptor’s blood—did not, for instance, reach its full vigour, if we consider what it had of Roman as distinct from Greek, until the Christian Era.46 It even made a discovery which affected all sculpture to come. The Greeks painted the eyes of marble statues and made out of enamel or glass or precious stones those of their bronze statues, but the Roman was the first to drill a round hole to represent the pupil, and because, as I think, of a preoccupation with the glance characteristic of a civilisation in its final phase.47 The colours must have already faded from the marbles of the great period, and a shadow and a spot of light, especially where there is much sunlight, are more vivid than paint, enamel, coloured glass or precious stone. They could now express in stone a perfect composure. The administrative mind, alert attention had driven out rhythm, exaltation of the body, uncommitted energy. May it not have been precisely a talent for this alert attention that had enabled Rome and not Greece to express those final primary phases? One sees on the pediments troops of marble Senators, officials serene and watchful as befits men who know that all the power of the world moves before their eyes, and needs, that it may not dash itself to pieces, their unhurried, unanxious, never-ceasing care. Those riders upon the Parthenon had all the world’s power in their moving bodies, and in a movement that seemed, so were the hearts of man and beast set upon it, that of a dance; but presently all would change and measurement succeed to pleasure, the dancing-master outlive the dance.48 What need had those young lads for careful eyes? But in Rome of the first and second centuries, where the dancing-master himself has died, the delineation of character as shown in face and head, as with us of recent years, is all in all, and sculptors, seeking the custom of occupied officials, stock in their workshops toga’d marble bodies upon which can be screwed with the least possible delay heads modelled from the sitters with the most scrupulous realism.49 When I think of Rome I see always those heads with their world-considering eyes, and those bodies as conventional as the metaphors in a leading article, and compare in my imagination vague Grecian eyes gazing at nothing, Byzantine eyes of drilled ivory staring upon a vision, and those eyelids of China and of India, those veiled or half-veiled eyes weary of world and vision alike.50

Meanwhile the irrational force that would create confusion and uproar as with the cry “The Babe, the Babe is born”51—the women speaking unknown tongues, the barbers and weavers expounding Divine revelation with all the vulgarity of their servitude, the tables that move or resound with raps—but creates a negligible sect.52

All about it is an antithetical aristocratic civilisation in its completed form, every detail of life hierarchical, every great man’s door crowded at dawn by petitioners, great wealth everywhere in few men’s hands, all dependent upon a few, up to the Emperor himself who is a God dependent upon a greater God, and everywhere in court, in the family, an inequality made law, and floating over all the Romanised Gods of Greece in their physical superiority.53 All is rigid and stationary, men fight for centuries with the same sword and spear, and though in naval warfare there is some change of tactics to avoid those single combats of ship with ship that needed the seamanship of a more skilful age, the speed of a sailing ship remains unchanged from the time of Pericles to that of Constantine.54 Though sculpture grows more and more realistic and so renews its vigour, this realism is without curiosity. The athlete becomes the boxer that he may show lips and nose beaten out of shape, the individual hairs show at the navel of the bronze centaur, but the theme has not changed. Philosophy alone, where in contact with irrational force—holding to Egyptian thaumaturgy and the Judean miracle but at arm’s length—can startle and create.55 Yet Plotinus is as primary, as much a contradiction of all that created Roman civilisation, as St. Peter, and his thought has its roots almost as deep among the primary masses. The founder of his school was Ammonius Sacca, an Alexandrine porter.56 His thought and that of Origen, which I skimmed in my youth,57 seem to me to express the abstract synthesis of a quality like that of race, and so to display a character which must always precede Phase 8.58 Origen, because the Judean miracle has a stronger hold upon the masses than Alexandrian thaumaturgy, triumphs when Constantine (Phase 8) puts the Cross upon the shields of his soldiers and makes the bit of his war-horse from a nail of the True Cross, an act equivalent to man’s cry for strength amid the animal chaos at the close of the first lunar quarter. Seeing that Constantine was not converted till upon his deathbed, I see him as half statesman, half thaumaturgist, accepting in blind obedience to a dream the new fashionable talisman, two sticks nailed together.59 The Christians were but six millions of the sixty or seventy of the Roman Empire, but, spending nothing upon pleasure, exceedingly rich like some Nonconformist sect of the eighteenth century. The world became Christian, “that fabulous formless darkness” as it seemed to a philosopher of the fourth century, blotted out “every beautiful thing”, not through the conversion of crowds or general change of opinion, or through any pressure from below, for civilization was antithetical still, but by an act of power.60

I have not the knowledge (it may be that no man has the knowledge) to trace the rise of the Byzantine State through Phases 9, 10 and 11.61 My diagram tells me that a hundred and sixty years brought that State to its 15th Phase, but I that know nothing but the arts and of these little, cannot revise the series of dates “approximately correct” but given, it may be, for suggestion only.62 With a desire for simplicity of statement I would have preferred to find in the middle, not at the end, of the fifth century Phase 12, for that was, so far as the known evidence carries us, the moment when Byzantium became Byzantine and substituted for formal Roman magnificence, with its glorification of physical power, an architecture that suggests the Sacred City in the Apocalypse of St. John.63 I think if I could be given a month of Antiquity and leave to spend it where I chose, I would spend it in Byzantium a little before Justinian opened St. Sophia and closed the Academy of Plato.64 I think I could find in some little wine-shop some philosophical worker in mosaic who could answer all my questions, the supernatural descending nearer to him than to Plotinus even, for the pride of his delicate skill would make what was an instrument of power to princes and clerics, a murderous madness in the mob, show as a lovely flexible presence like that of a perfect human body.65

I think that in early Byzantium, maybe never before or since in recorded history, religious, aesthetic and practical life were one, that architect and artificers—though not, it may be, poets, for language had been the instrument of controversy and must have grown abstract—spoke to the multitude and the few alike.66 The painter, the mosaic worker, the worker in gold and silver, the illuminator of sacred books, were almost impersonal, almost perhaps without the consciousness of individual design, absorbed in their subject-matter and that the vision of a whole people. They could copy out of old Gospel books those pictures that seemed as sacred as the text, and yet weave all into a vast design, the work of many that seemed the work of one, that made building, picture, pattern, metal-work of rail and lamp, seem but a single image; and this vision, this proclamation of their invisible master, had the Greek nobility, Satan always the still half-divine Serpent, never the horned scarecrow of the didactic Middle Ages.67

The ascetic, called in Alexandria “God’s Athlete”, has taken the place of those Greek athletes whose statues have been melted or broken up or stand deserted in the midst of cornfields, but all about him is an incredible splendour like that which we see pass under our closed eyelids as we lie between sleep and waking, no representation of a living world but the dream of a somnambulist.68 Even the drilled pupil of the eye, when the drill is in the hand of some Byzantine worker in ivory, undergoes a somnambulistic change, for its deep shadow among the faint lines of the tablet, its mechanical circle, where all else is rhythmical and flowing, give to Saint or Angel a look of some great bird staring at miracle.69 Could any visionary of those days, passing through the Church named with so un-theological a grace “The Holy Wisdom”,70 can even a visionary of to-day wandering among the mosaics at Ravenna or in Sicily, fail to recognise some one image seen under his closed eyelids?71 To me it seems that He, who among the first Christian communities was little but a ghostly exorcist, had in His assent to a full Divinity made possible this sinking-in upon a supernatural splendour, these walls with their little glimmering cubes of blue and green and gold.

I think that I might discover an oscillation, a revolution of the horizontal gyre like that between Doric and Ionic art, between the two principal characters of Byzantine art. Recent criticism distinguishes between Greco-Roman figures, their stern faces suggesting Greek wall-painting at Palmyra, Greco-Egyptian painting upon the cases of mummies, where character delineations are exaggerated as in much work of our time, and that decoration which seems to undermine our self-control, and is, it seems, of Persian origin, and has for its appropriate symbol a vine whose tendrils climb everywhere and display among their leaves all those strange images of bird and beast, those forms that represent no creature eye has ever seen, yet are begotten one upon the other as if they were themselves living creatures.72 May I consider the domination of the first antithetical and that of the second primary, and see in their alternation the work of the horizontal gyre? Strzygowski thinks that the church decorations where there are visible representations of holy persons were especially dear to those who believed in Christ’s double nature, and that wherever Christ is represented by a bare Cross and all the rest is bird and beast and tree, we may discover an Asiatic art dear to those who thought Christ contained nothing human.73

If I were left to myself I would make Phase 15 coincide with Justinian’s reign, that great age of building in which one may conclude Byzantine art was perfected; but the meaning of the diagram may be that a building like St. Sophia, where all, to judge by the contemporary description, pictured ecstasy, must unlike the declamatory St. Peter’s precede the moment of climax.74 Of the moment of climax itself I can say nothing, and of what followed from Phase 17 to Phase 21 almost nothing, for I have no knowledge of the time; and no analogy from the age after Phidias, or after our own Renaissance, can help.75 We and the Greeks moved towards intellect, but Byzantium and the Western Europe of that day moved from it. If Strzygowski is right we may see in the destruction of images but a destruction of what was Greek in decoration accompanied perhaps by a renewed splendour in all that came down from the ancient Persian Paradise, an episode in some attempt to make theology more ascetic, spiritual and abstract. Destruction was apparently suggested to the first iconoclastic Emperor by followers of a Monophysite Bishop, Xenaias, who had his see in that part of the Empire where Persian influence had been strongest.76 The return of the images may, as I see things, have been the failure of synthesis (Phase 22) and the first sinking-in and dying-down of Christendom into the heterogeneous loam. Did Europe grow animal and literal? Did the strength of the victorious party come from zealots as ready as their opponents to destroy an image if permitted to grind it into powder, mix it with some liquid and swallow it as a medicine?77 Did mankind for a season do, not what it would, or should, but what it could, accept the past and the current belief because they prevented thought? In Western Europe I think I may see in Johannes Scotus Erigena the last intellectual synthesis before the death of philosophy, but I know little of him except that he is founded upon a Greek book of the sixth century, put into circulation by a last iconoclastic Emperor, though its Angelic Orders gave a theme to the image-makers.78 I notice too that my diagram makes Phase 22 coincide with the break-up of Charlemagne’s Empire and so clearly likens him to Alexander, but I do not want to concern myself, except where I must, with political events.79

Then follows, as always must in the last quarter,80 heterogeneous art; hesitation amid architectural forms, some book tells me; an interest in Greek and Roman literature; much copying out and gathering together; yet outside a few courts and monasteries another book tells me an Asiatic and anarchic Europe.81 The intellectual cone has so narrowed that secular intellect has gone, and the strong man rules with the aid of local custom; everywhere the supernatural is sudden, violent, and as dark to the intellect as a stroke or St. Vitus’ dance.82 Men under the Caesars, my own documents tell me, were physically one but intellectually many, but that is now reversed, for there is one common thought or doctrine, town is shut off from town, village from village, clan from clan. The spiritual life is alone overflowing, its cone expanded, and yet this life—secular intellect extinguished—has little effect upon men’s conduct, is perhaps a dream which passes beyond the reach of conscious mind but for some rare miracle or vision. I think of it as like that profound reverie of the somnambulist which may be accompanied by a sensuous dream—a Romanesque stream perhaps of bird and beast images—and yet neither affect the dream nor be affected by it.83

It is indeed precisely because this double mind is created at full moon that the antithetical phases are but, at the best, phases of a momentary illumination like that of a lightning flash. But the full moon that now concerns us is not only Phase 15 of its greater era, but the final phase, Phase 28, of its millennium, and in its physical form, human life grown once more automatic. I knew a man once who, seeking for an image of the Absolute, saw one persistent image, a slug, as though it were suggested to him that Being which is beyond human comprehension is mirrored in the least organised forms of life. Intellectual creation has ceased, but men have come to terms with the supernatural and are agreed that, if you make the usual offerings, it will remember to live and let live; even Saint or Angel does not seem very different from themselves: a man thinks his guardian Angel jealous of his mistress;84 a King, dragging a Saint’s body to a new church, meets some difficulty upon the road, assumes a miracle, and denounces the Saint as a churl. Three Roman courtesans who have one after another got their favourite lovers chosen Pope have, it pleases one’s mockery to think, confessed their sins, with full belief in the supernatural efficacy of the act, to ears that have heard their cries of love, or received the Body of God from hands that have played with their own bodies.85 Interest has narrowed to what is near and personal and, seeing that all abstract secular thought has faded, those interests have taken the most physical forms. In monasteries and in hermit cells men freed from the intellect at last can seek their God upon all fours like beasts or children. Ecclesiastical Law, in so far as that law is concerned not with government, Church or State, but with the individual soul, is complete; all that is necessary to salvation is known, yet there is apathy everywhere. Man awaits death and judgment with nothing to occupy the worldly faculties and helpless before the world’s disorder, drags out of the subconscious the conviction that the world is about to end. Hidden, except at rare moments of excitement or revelation, even then shown but in symbol, the stream set in motion by the Galilean Symbol has filled its basin, and seems motionless for an instant before it falls over the rim. In the midst of the basin stands, in motionless contemplation, blood that is not His blood upon His Hands and Feet, One that feels but for the common lot, and mourns over the length of years and the inadequacy of man’s fate to man. Two thousand years before, His predecessor, careful of heroic men alone, had so stood and mourned over the shortness of time, and man’s inadequacy to his fate.

Full moon over, that last Embodiment shall grow more like ourselves, putting off that stern majesty, borrowed, it may be, from the Phidian Zeus—if we can trust Cefalù and Monreale; and His Mother—putting off her harsh Byzantine image—stand at His side.86

V

A.D. 1050 to the Present Day

When the tide changed and faith no longer sufficed, something must have happened in the courts and castles of which history has perhaps no record, for with the first vague dawn of the ultimate antithetical revelation man, under the eyes of the Virgin, or upon the breast of his mistress, became but a fragment. Instead of that old alternation, brute or ascetic, came something obscure or uncertain that could not find its full explanation for a thousand years. A certain Byzantine Bishop had said upon seeing a singer of Antioch, “I looked long upon her beauty, knowing that I would behold it upon the day of judgment, and I wept to remember that I had taken less care of my soul than she of her body”,87 but when in the Arabian Nights Harun Al-Rashid looked at the singer Heart’s Miracle, and on the instant loved her, he covered her head with a little silk veil to show that her beauty “had already retreated into the mystery of our faith”.88 The Bishop saw a beauty that would be sanctified, but the Caliph that which was its own sanctity, and it was this latter sanctity, come back from the first Crusade or up from Arabian Spain or half Asiatic Provence and Sicily, that created romance. What forgotten reverie, what initiation, it may be, separated wisdom from the monastery and, creating Merlin, joined it to passion? When Merlin in Chrestien de Troyes loved Ninian he showed her a cavern adorned with gold mosaics and made by a prince for his beloved, and told her that those lovers died upon the same day and were laid “in the chamber where they found delight”. He thereupon lifted a slab of red marble that his art alone could lift and showed them wrapped in winding-sheets of white samite. The tomb remained open, for Ninian asked that she and Merlin might return to the cavern and spend their night near those dead lovers, but before night came Merlin grew sad and fell asleep, and she and her attendants took him “by head and foot” and laid him “in the tomb and replaced the stone”, for Merlin had taught her the magic words, and “from that hour none beheld Merlin dead or alive”.89 Throughout the German Parsifal there is no ceremony of the Church, neither Marriage nor Mass nor Baptism, but instead we discover that strangest creation of romance or of life, “the love trance”. Parsifal in such a trance, seeing nothing before his eyes but the image of his absent love, overcame knight after knight, and awakening at last looked amazed upon his dinted sword and shield; and it is to his lady and not to God or the Virgin that Parsifal prayed upon the day of battle, and it was his lady’s soul, separated from her entranced or sleeping body, that went beside him and gave him victory.90

The period from 1050 to 1180 is attributed in the diagram to the first two gyres of our millennium, and what interests me in this period, which corresponds to the Homeric period some two thousand years before, is the creation of the Arthurian Tales and Romanesque architecture. I see in Romanesque the first movement to a secular Europe, but a movement so instinctive that as yet there is no antagonism to the old condition. Every architect, every man who lifts a chisel, may be a cleric of some kind, yet in the overflowing ornament where the human form has all but disappeared and where no bird or beast is copied from nature, where all is more Asiatic than Byzantium itself, one discovers the same impulse that created Merlin and his jugglery.

I do not see in Gothic architecture, which is a character of the next gyre, that of Phases 5, 6 and 7, as did the nineteenth-century historians, ever looking for the image of their own age, the creation of a new communal freedom, but a creation of authority, a suppression of that freedom though with its consent, and certainly St. Bernard when he denounced the extravagance of Romanesque saw it in that light.91 I think of that curious sketchbook of Villard de Honnecourt with its insistence upon mathematical form, and I see that form in Mont St. Michel—Church, Abbey, Fort and town, all that dark geometry that makes Byzantium seem a sunlit cloud—and it seems to me that the Church grows secular that it may fight a new-born secular world.92 Its avowed appeal is to religion alone: nobles and great ladies join the crowds that drag the Cathedral stones, not out of love for beauty but because the stones as they are trundled down the road cure the halt and the blind; yet the stones once set up traffic with the enemy. The mosaic pictures grown transparent93 fill the windows, quarrel one with the other like pretty women, and draw all eyes, and upon the faces of the statues flits once more the smile that disappeared with archaic Greece. That smile is physical, primary joy, the escape from supernatural terror, a moment of irresponsible common life before antithetical sadness begins. It is as though the pretty worshippers, while the Dominican was preaching with a new and perhaps incredible sternness, let their imaginations stray, as though the observant sculptor, or worker in ivory, in modelling his holy women has remembered their smiling lips.94

Are not the cathedrals and the philosophy of St. Thomas the product of the abstraction that comes before Phase 8 as before Phase 22, and of the moral synthesis that at the end of the first quarter seeks to control the general anarchy?95 That anarchy must have been exceedingly great, or man must have found a hitherto unknown sensitiveness, for it was the shock that created modern civilisation. The diagram makes the period from 1250 to 1300 correspond to Phase 8, certainly because in or near that period, chivalry and Christendom having proved insufficient, the King mastered the one, the Church the other, reversing the achievement of Constantine, for it was now the mitre and the crown that protected the Cross.96 I prefer, however, to find my example of the first victory of personality where I have more knowledge. Dante in the Convito mourns for solitude, lost through poverty, and writes the first sentence of modern autobiography, and in the Divina Commedia imposes his own personality upon a system and a phantasmagoria hitherto impersonal; the King everywhere has found his kingdom.97

The period from 1300 to 1380 is attributed to the fourth gyre, that of Phases 9, 10 and 11, which finds its character in painting from Giotto to Fra Angelico, in the Chronicles of Froissart and in the elaborate canopy upon the stained glass of the windows.98 Every old tale is alive, Christendom still unbroken; painter and poet alike find new ornament for the tale, they feel the charm of everything but the more poignantly because that charm is archaistic; they smell a pot of dried roses. The practical men, face to face with rebellion and heresy, are violent as they have not been for generations, but the artists separated from life by the tradition of Byzantium can even exaggerate their gentleness, and gentleness and violence alike express the gyre’s hesitation. The public certainty that sufficed for Dante and St. Thomas has disappeared, and there is yet no private certainty. Is it that the human mind now longs for solitude, for escape from all that hereditary splendour, and does not know what ails it; or is it that the Image itself encouraged by the new technical method, the flexible brush-stroke instead of the unchanging cube of glass, and wearied of its part in a crowded ghostly dance, longs for a solitary human body? That body comes in the period from 1380 to 1450 and is discovered by Masaccio, and by Chaucer who is partly of the old gyre, and by Villon who is wholly of the new.99

Masaccio, a precocious and abundant man, dying like Aubrey Beardsley in his six-and-twentieth year, cannot move us, as he did his immediate successors, for he discovered a naturalism that begins to weary us a little;100 making the naked young man awaiting baptism shiver with the cold, St. Peter grow red with the exertion of dragging the money out of the miraculous fish’s mouth, while Adam and Eve, flying before the sword of the Angel, show faces disfigured by their suffering.101 It is very likely because I am a poet and not a painter that I feel so much more keenly that suffering of Villon—of the 13th Phase as man, and of it or near it in epoch—in whom the human soul for the first time stands alone before a death ever present to imagination, without help from a Church that is fading away; or is it that I remember Aubrey Beardsley, a man of like phase though so different epoch, and so read into Villon’s suffering our modern conscience which gathers intensity as we approach the close of an era?102 Intensity that has seemed to me pitiless self-judgment may have been but heroic gaiety. With the approach of solitude bringing with it an ever-increasing struggle with that which opposes solitude—sensuality, greed, ambition, physical curiosity in all its species—philosophy has returned driving dogma out. Even amongst the most pious the worshipper is preoccupied with himself, and when I look for the drilled eyeball, which reveals so much, I notice that its edge is no longer so mechanically perfect, nor, if I can judge by casts at the Victoria and Albert Museum, is the hollow so deep.103 Angel and Florentine noble must look upward with an eye that seems dim and abashed as though to recognise duties to Heaven, an example to be set before men, and finding both difficult seem a little giddy. There are no miracles to stare at, for man descends the hill he once climbed with so great toil, and all grows but natural again.

As we approach the 15th Phase, as the general movement grows more and more westward in character, we notice the oscillation of the horizontal gyres, as though what no Unity of Being, yet possible, can completely fuse displays itself in triumph.

Donatello, as later Michelangelo, reflects the hardness and astringency of Myron, and foretells what must follow the Renaissance; while Jacopo della Quercia and most of the painters seem by contrast, as Raphael later on, Ionic and Asiatic.104 The period from 1450 to 1550 is allotted to the gyre of Phase 15, and these dates are no doubt intended to mark somewhat vaguely a period that begins in one country earlier and in another later. I do not myself find it possible to make more than the first half coincide with the central moment, Phase 15 of the Italian Renaissance—Phase 22 of the cone of the entire era—the breaking of the Christian synthesis as the corresponding period before Christ, the age of Phidias, was the breaking of Greek traditional faith. The first half covers the principal activity of the Academy of Florence which formulated the reconciliation of Paganism and Christianity.105 This reconciliation, which to Pope Julius meant that Greek and Roman Antiquity were as sacred as that of Judea, and like it “a vestibule of Christianity”, meant to the mind of Dürer—a visitor to Venice during the movement of the gyre—that the human norm, discovered from the measurement of ancient statues, was God’s first handiwork, that “perfectly proportioned human body” which had seemed to Dante Unity of Being symbolised.106 The ascetic, who had a thousand years before attained his transfiguration upon the golden ground of Byzantine mosaic, had turned not into an athlete but into that unlabouring form the athlete dreamed of: the second Adam had become the first.107

Because the 15th Phase can never find direct human expression, being a supernatural incarnation, it impressed upon work and thought an element of strain and artifice, a desire to combine elements which may be incompatible, or which suggest by their combination something supernatural. Had some Florentine Platonist read to Botticelli Porphyry upon the Cave of the Nymphs? for I seem to recognise it in that curious cave, with a thatched roof over the nearer entrance to make it resemble the conventional manger, in his “Nativity”II in the National Gallery.108 Certainly the glimpse of forest trees, dim in the evening light, through the far entrance, and the deliberate strangeness everywhere, gives one an emotion of mystery which is new to painting.

Botticelli, Crivelli, Mantegna, Da Vinci,109 who fall within the period, make Masaccio and his school seem heavy and common by something we may call intellectual beauty or compare perhaps to that kind of bodily beauty which Castiglione called “the spoil or monument of the victory of the soul”.110 Intellect and emotion, primary curiosity and the antithetical dream, are for the moment one. Since the rebirth of the secular intellect in the eleventh century, faculty has been separating from faculty, poetry from music, the worshipper from the worshipped, but all have remained within a common fading circle—Christendom—and so within the human soul. Image has been separated from image but always as an exploration of the soul itself; forms have been displayed in an always clear light, have been perfected by separation from one another till their link with one another and with common associations has been broken; but, Phase 15 past, these forms begin to jostle and fall into confusion, there is as it were a sudden rush and storm.111 In the mind of the artist a desire for power succeeds to that for knowledge, and this desire is communicated to the forms and to the onlooker.

The eighth gyre, which corresponds to Phases 16, 17 and 18 and completes itself say between 1550 and 1650, begins with Raphael, Michelangelo and Titian, and the forms, as in Titian, awaken sexual desire112—we had not desired to touch the forms of Botticelli or even of Da Vinci—or they threaten us like those of Michelangelo, and the painter himself handles his brush with a conscious facility or exultation. The subject-matter may arise out of some propaganda as when Raphael in the Camera della Segnatura, and Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel, put, by direction of the Pope, Greek Sages and Doctors of the Church, Roman Sibyls and Hebrew Prophets, opposite one another in apparent equality.113 From this on, all is changed, and where the Mother of God sat enthroned, now that the Soul’s unity has been found and lost, Nature seats herself, and the painter can paint only what he desires in the flesh, and soon, asking less and less for himself, will make it a matter of pride to paint what he does not at all desire. I think Raphael almost of the earlier gyre—perhaps a transitional figure—but Michelangelo, Rabelais, Aretino, Shakespeare, Titian—Titian is so markedly of the 14th Phase as a man that he seems less characteristic—I associate with the mythopoeic and ungovernable beginning of the eighth gyre. I see in Shakespeare a man in whom human personality, hitherto restrained by its dependence upon Christendom or by its own need for self-control, burst like a shell. Perhaps secular intellect, setting itself free after five hundred years of struggle, has made him the greatest of dramatists, and yet because an antithetical age alone could confer upon an art like his the unity of a painting or of a temple pediment, we might, had the total works of Sophocles survived—they too born of a like struggle though with a different enemy—not think him greatest. Do we not feel an unrest like that of travel itself when we watch those personages, more living than ourselves, amid so much that is irrelevant and heterogeneous, amid so much primary curiosity, when we are carried from Rome to Venice, from Egypt to Saxon England, or in the one play from Roman to Christian mythology?

Were he not himself of a later phase, were he of the 16th Phase like his age and so drunk with his own wine, he had not written plays at all, but as it is he finds his opportunity among a crowd of men and women who are still shaken by thought that passes from man to man in psychological contagion. I see in Milton, who is characteristic of the moment when the first violence of the gyre has begun to sink, an attempted return to the synthesis of the Camera della Segnatura and the Sistine Chapel. It is this attempt made too late that, amid all the music and magnificence of the still violent gyre, gives him his unreality and his cold rhetoric. The two elements have fallen apart in the hymn “On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity”, the one is sacred, the other profane; his classical mythology is an artificial ornament;114 whereas no great Italian artist from 1450 to the sack of Rome saw any difference between them, and when difference came, as it did with Titian, it was God and the Angels that seemed artificial.

The gyre ebbs out in order and reason, the Jacobean poets succeed the Elizabethan, Cowley and Dryden the Jacobean as belief dies out.115 Elsewhere Christendom keeps a kind of spectral unity for a while, now with one, now with the other element of the synthesis dominant; a declamatory holiness defaces old churches, innumerable Tritons and Neptunes pour water from their mouths. What had been a beauty like the burning sun fades out in Vandyke’s noble ineffectual faces, and the Low Countries, which have reached the new gyre long before the rest of Europe, convert the world to a still limited curiosity, to certain recognised forms of the picturesque constantly repeated, chance travellers at an inn door, men about a fire, men skating, the same pose or grouping, where the subject is different, passing from picture to picture.116 The world begins to long for the arbitrary and accidental, for the grotesque, the repulsive and the terrible, that it may be cured of desire. The moment has come for the ninth gyre, Phases 19, 20 and 21, for the period that begins for the greater part of Europe with 1650 and lasts, it may be, to 1875.

The beginning of the gyre like that of its forerunner is violent, a breaking of the soul and world into fragments, and has for a chief character the materialistic movement at the end of the seventeenth century, all that comes out of Bacon perhaps, the foundation of our modern inductive reasoning, the declamatory religious sects and controversies that first in England and then in France destroy the sense of form, all that has its very image and idol in Bernini’s big Altar in St. Peter’s with its figures contorted and convulsed by religion as though by the devil.117 Men change rapidly from deduction to deduction, opinion to opinion, have but one impression at a time and utter it always, no matter how often they change, with the same emphasis. Then the gyre develops a new coherence in the external scene; and violent men, each master of some generalisation, arise one after another: Napoleon, a man of the 20th Phase in the historical 21st—personality in its hard final generalisation—typical of all. The artistic life, where most characteristic of the general movement, shows the effect of the closing of the tinctures. It is external, sentimental and logical—the poetry of Pope and Gray, the philosophy of Johnson and of Rousseau—equally simple in emotion or in thought, the old oscillation in a new form.118 Personality is everywhere spreading out its fingers in vain, or grasping with an always more convulsive grasp a world where the predominance of physical science, of finance and economics in all their forms, of democratic politics, of vast populations, of architecture where styles jostle one another, of newspapers where all is heterogeneous, show that mechanical force will in a moment become supreme.

That art discovered by Dante of marshalling into a vast antithetical structure antithetical material became through Milton Latinised and artificial—the Shades, as Sir Thomas Browne said, “steal or contrive a body”119—and now it changes that it may marshal into a still antithetical structure primary material, and the modern novel is created, but even before the gyre is drawn to its end the happy ending, the admired hero, the preoccupation with desirable things, all that is undisguisedly antithetical disappears.

All the art of the gyre that is not derived from the external scene is a Renaissance echo growing always more conventional or more shadowy, but since the Renaissance—Phase 22 of the cone of the era—the “Emotion of Sanctity”, that first relation to the spiritual primary, has been possible in those things that are most intimate and personal, though not until Phase 22 of the millennium cone will general thought be ready for its expression.120 A mysterious contact is perceptible first in painting and then in poetry and last in prose. In painting it comes where the influence of the Low Countries and that of Italy mingle, but always rarely and faintly. I do not find it in Watteau, but there is a preparation for it, a sense of exhaustion of old interests—“they do not believe even in their own happiness”, Verlaine said—and then suddenly it is present in the faces of Gainsborough’s women as it has been in no face since the Egyptian sculptor buried in a tomb that image of a princess carved in wood.121 Reynolds had nothing of it, an ostentatious fashionable man fresh from Rome, he stayed content with fading Renaissance emotion and modern curiosity.122 In frail women’s faces the soul awakes—all its prepossessions, the accumulated learning of centuries swept away—and looks out upon us wise and foolish like the dawn. Then it is everywhere, it finds the village Providence of the eighteenth century and turns him into Goethe, who for all that comes to no conclusion, his Faust after his hundred years but reclaiming land like some Sir Charles Grandison or Voltaire in his old age.123 It makes the heroines of Jane Austen seek, not as their grandfathers and grandmothers would have done, theological or political truth, but simply good breeding, as though to increase it were more than any practical accomplishment.124 In poetry alone it finds its full expression, for it is a quality of the emotional nature (Celestial Body acting through Mask); and creates all that is most beautiful in modern English poetry from Blake to Arnold, all that is not a fading echo. One discovers it in those symbolist writers who like Verhaeren substitute an entirely personal wisdom for the physical beauty or passionate emotion of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.125 In painting it shows most often where the aim has been archaistic, as though it were an accompaniment of what the popular writers call decadence, as though old emotions had first to be exhausted. I think of the French portrait-painter Ricard, to whom it was more a vision of the mind than a research, for he would say to his sitter, “You are so fortunate as to resemble your picture”, and of Charles Ricketts, my education in so many things.126 How often his imagination moves stiffly as though in fancy dress, and then there is something—Sphinx, Danaides—that makes me remember Callimachus’ return to Ionic elaboration and shudder as though I stared into an abyss full of eagles. Everywhere this vision, or rather this contact, is faint or intermittent and it is always fragile; Dickens was able with a single book, Pickwick, to substitute for Jane Austen’s privileged and perilous research the camaraderie of the inn parlour, qualities that every man might hope to possess, and it did not return till Henry James began to write.127

Certain men have sought to express the new emotion through the Creative Mind, though fit instruments of expression do not yet exist, and so to establish, in the midst of our ever more abundant primary information, antithetical wisdom; but such men, Blake, Coventry Patmore at moments, Nietzsche, are full of morbid excitement and few in number, unlike those who, from Richardson to Tolstoy, from Hobbes down to Spencer, have grown in number and serenity.128 They were begotten in the Sistine Chapel and still dream that all can be transformed if they be but emphatic; yet Nietzsche, when the doctrine of the Eternal Recurrence drifts before his eyes, knows for an instant that nothing can be so transformed and is almost of the next gyre.129

The period from 1875 to 1927 (Phase 22—in some countries and in some forms of thought the phase runs from 1815 to 1927) is like that from 1250 to 1300 (Phase 8) a period of abstraction, and like it also in that it is preceded and followed by abstraction. Phase 8 was preceded by the Schoolmen and followed by legalists and inquisitors, and Phase 22 was preceded by the great popularisers of physical science and economic science, and will be followed by social movements and applied science. Abstraction which began at Phase 19 will end at Phase 25, for these movements and this science will have for their object or result the elimination of intellect. Our generation has witnessed a first weariness, has stood at the climax, at what in The Trembling of the Veil I call Hodos Chameliontos, and when the climax passes will recognise that there common secular thought began to break and disperse.130 Tolstoy in War and Peace had still preference, could argue about this thing or that other, had a belief in Providence and a disbelief in Napoleon, but Flaubert in his St. Anthony had neither belief nor preference, and so it is that, even before the general surrender of the will, there came synthesis for its own sake, organisation where there is no masterful director, books where the author has disappeared, painting where some accomplished brush paints with an equal pleasure, or with a bored impartiality, the human form or an old bottle, dirty weather and clean sunshine.131 I too think of famous works where synthesis has been carried to the utmost limit possible, where there are elements of inconsequence or discovery of hitherto ignored ugliness, and I notice that when the limit is approached or past, when the moment of surrender is reached, when the new gyre begins to stir, I am filled with excitement. I think of recent mathematical research; even the ignorant can compare it with that of Newton—so plainly of the 19th Phase—with its objective world intelligible to intellect; I can recognise that the limit itself has become a new dimension, that this ever-hidden thing which makes us fold our hands has begun to press down upon multitudes.132 Having bruised their hands upon that limit, men, for the first time since the seventeenth century, see the world as an object of contemplation, not as something to be remade, and some few, meeting the limit in their special study, even doubt if there is any common experience, doubt the possibility of science.133

. . . . .

Written at Capri, February 1925

THE END OF THE CYCLE134

I

Day after day I have sat in my chair turning a symbol over in my mind, exploring all its details, defining and again defining its elements, testing my convictions and those of others by its unity, attempting to substitute particulars for an abstraction like that of algebra. I have felt the convictions of a lifetime melt though at an age when the mind should be rigid, and others take their place, and these in turn give way to others. How far can I accept socialistic or communistic prophecies? I remember the decadence Balzac foretold to the Duchess de Castries.135 I remember debates in the little coach-house at Hammersmith or at Morris’ supper-table afterwards.136 I remember the Apocalyptic dreams of the Japanese Saint and labour leader Kagawa, whose books were lent me by a Galway clergyman.137 I remember a Communist described by Captain White in his memoirs ploughing on the Cotswold Hills, nothing on his great hairy body but sandals and a pair of drawers, nothing in his head but Hegel’s Logic.138 Then I draw myself up into the symbol and it seems as if I should know all if I could but banish such memories and find everything in the symbol.

II

But nothing comes—though this moment was to reward me for all my toil. Perhaps I am too old. Surely something would have come when I meditated under the direction of the Cabbalists. What discords will drive Europe to that artificial unity—only dry or drying sticks can be tied into a bundle—which is the decadence of every civilisation?139 How work out upon the phases the gradual coming and increase of the counter movement, the antithetical multiform influx:

Should Jupiter and Saturn meet,

O what a crop of mummy wheat!140

Then I understand. I have already said all that can be said. The particulars are the work of the Thirteenth Cone or cycle which is in every man and called by every man his freedom. Doubtless, for it can do all things and knows all things, it knows what it will do with its own freedom but it has kept the secret.

III

Shall we follow the image of Heracles that walks through the darkness bow in hand, or mount to that other Heracles, man, not image, he that has for his bride Hebe, “The daughter of Zeus, the mighty, and Hera, shod with gold”?141

1934–1936

I. Toynbee considers Greece the heir of Crete, and that Greek religion inherits from the Minoan monotheistic mother goddess its more mythical conceptions (A Study of History, vol. i, p. 92). “Mathematic Starlight” Babylonian astrology is, however, present in the friendships and antipathies of the Olympic gods.9

II. There is a Greek inscription at the top of the picture which says that Botticelli’s world is in the “second woe” of the Apocalypse, and that after certain other Apocalyptic events the Christ of the picture will appear. He had probably found in some utterance of Savonarola’s promise of an ultimate Marriage of Heaven and Earth, sacred and profane, and pictures it by the Angels and shepherds embracing, and as I suggest by Cave and Manger. When I saw the Cave of Mithra at Capri I wondered if that were Porphyry’s Cave. The two entrances are there, one reached by a stair of a hundred feet or so from the sea and once trodden by devout sailors, and one reached from above by some hundred and fifty steps and used, my guide-book tells me, by Priests. If he knew that cave, which may have had its recognised symbolism, he would have been the more ready to discover symbols in the cave where Odysseus landed in Ithaca.