Making Sense of Shipibo-Conibo Designs

This chapter explores the question of how to make sense of the art of the Shipibo-Conibo Indians of the Peruvian Amazon (see Figures 4.1–4.3), a vexed issue that has foxed anthropologists for decades. The discussion will situate the designs in the context of the art of the Amazon region and the interpretive approaches that have historically been applied to these visual traditions. But while related and stylistically similar to much of the art of the region, Shipibo-Conibo designs stand out because of their sophistication, which has brought them to worldwide attention. This chapter reflects on the difficulty of ‘reading’ the designs in relation to larger issues of cultural translation in the field of anthropology, art and the global arena of contemporary visual culture. It examines the extent to which a reconfigured relational aesthetics that has been expanded into culture and encompasses a fuller range of Deleuze–Guattarean aesthetics can offer a bridging moment between the cultural worlds of the Amazon and the West.

The art of the Shipibo-Conibo Indians is considered ‘one of the most complex functioning art styles in the aboriginal New World’.1 It consists of intricate geometric designs applied to ceramic vessels and textiles, and is highly esteemed by art collectors around the globe. The indigenous peoples of the eastern foothills of the Andes and the western Amazon river basin, such as the Piro and Cashinahua, think highly of Shipibo-Conibo art and consider it the most evolved art in the region.2 The Shipibo-Conibo furthermore have successfully adapted their art to the interests of art institutions and collectors worldwide as well as to the tourism in the area.3 Women are the main producers of the art and benefit most from these developments, as the sale of the work, often through indigenous cooperatives, allows them to generate much-needed cash income. There are even some instances of individual fame to report, such as Anastasia Fernandez Maynas, a Shipibo-Conibo artist from San Francisco – from a small community near the eastern Peruvian market city Pucallpa – who established a worldwide reputation for the quality of her ceramics.4 Apart from institutional collections in the United States5 and in Germany,6 private collectors have also taken an interest in Shipibo-Conibo artefacts, and Shipibo-Conibo art is exhibited on a regular basis around the globe. A brief search on Google reveals many sites offering Shipibo ceramics for sale.7 Yet while in-depth research into Shipibo-Conibo art has been carried out, the meaning of the designs continues to puzzle researchers.

The debate about the meaning of the designs occurred within the field of anthropology, which historically deferred to art history’s expertise when discussing visual objects in the field, borrowing its terminology and approaches. Western conceptions of art have therefore set the tone for anthropology’s dealings with indigenous visual production,8 but these approaches no longer reflect current modalities in Western art theory. For the most part, anthropology has not kept abreast of the changes in art history and visual culture that have occurred since the initial incorporation of art historical conceptions into anthropology. The anthropologist Barbara Keifenheim who has taken a keen interest in the pattern art of the Cashinahua Indians and has also conducted fieldwork among the Shipibo-Conibo, is deeply critical of the iconographic-semantic approach derived from Western art that continues to be most commonly used in Amazonian art ethnology.9 The anthropologist Peter Gow, who studies the Piro people of the River Bajo Urubamba in eastern Peru, shares Keifenheim’s concern. He characterizes the iconographic-semantic approach as a method that treats designs as embodiments of ‘representational meaning, in the manner of writing systems’.10 For him this approach is inappropriate in the Amazon context and he is not surprised that it has not delivered a framework for making sense of the designs.

Despite the lack of success overall, there has been little rethinking of method. This is even more surprising because the discipline of anthropology has dramatically improved its visual acuity on other fronts. For instance, its sub-discipline, visual anthropology, explores the cultural and historical specificity of human vision.11 It has developed from a marginal pursuit within the discipline in the 1990s to a vibrant research area,12 and has pioneered the use of visual media such as film, video and photography as modes of ethnographic research, challenging anthropology’s reliance on the textual. The anthropology of the senses, another sub-discipline that emerged around this time, studies cultural difference in sensory perception. It emphasizes that sensual orders are deeply informed by, and need to be examined in relation to, the culturally specific perceptual worlds with which they are connected.13 Increasingly interdisciplinary, this anthropological sub-field draws on discussions in the fields of phenomenology, psychology, sociology, geography and so forth, and offers ‘renewed ways of thinking about the relationship between sensory categories and sensory perception’.14

But despite these lively discussions and innovations, anthropology’s concern with the visual stays focused on the exploration of human behaviour and perception within specific cultural contexts and does not consider art as central to its remit. Anthropology’s visual turn, therefore, so far has not considered indigenous visual cultures in relation to the larger spheres of art. The questions asked of the visual material encountered in the field remain largely within the bounds of the cultural specificity of fieldwork scenarios. Yet visual anthropology has instigated fascinating new departures that blur the boundaries between ethnography and contemporary art practice and has generated groundbreaking and compelling work in this area.15

The disciplinary lack of interest in the question of indigenous visual culture in relation to art per se reflects issues that the anthropologist George Marcus has raised. He points out that anthropology as a discipline has not yet acknowledged that the Malinowskian fieldwork model of the lone ethnographer working in bounded communities situated in a temporal and spatial ‘over-there’ no longer represents the contemporary, coeval fieldwork situation. Indigenous art thus no longer exists in an isolated bubble of pre-contact culture but is marked by histories of contact through conquest, colonialism and missionization. It furthermore participates in an increasingly pro-active way in the contemporary world. And as the world continues to globalize, so will its arts. The question of how to approach these forms of art making in a way that bypasses dominant Eurocentric preconceptions is therefore ever more urgent. It will be explored in what follows with a primary focus on Shipibo-Conibo designs but discussions of the art of the neighbouring Piro and Cashinahua with related art styles will also be drawn upon.

The Shipibo-Conibo Design Language

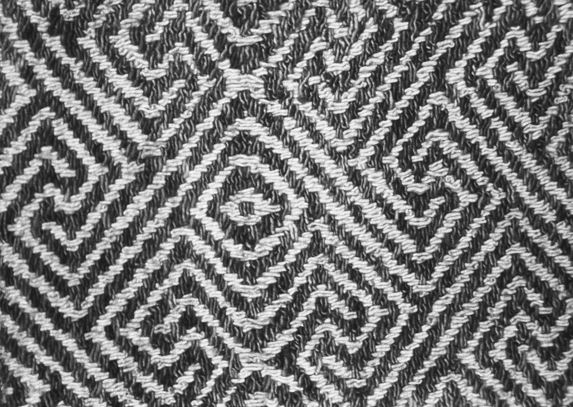

The discussion of Shipibo-Conibo designs is largely based on the work of Angelika Gebhart-Sayer who informs us that the designs belong to the realm of female activity and consist of abstract, loosely geometric, regularly spaced patterns applied to ceramic vessels and textiles. The design language consists of two basic elements: fine linear compositions, or quene and block-like compositions in bold lattices, or canoa (see Figures 4.1 and 4.2).

Both types of designs are developed in symmetrical repetitions organized in distinct areas marked by ‘boundary’ lines. Vessels carry several design motifs and types16 that are developed in one of these areas. The designs are always uniformly spaced and would extend in all directions if not brought to a halt by demarcation lines. The designs, according to Gebhart-Sayer, are composed of ‘form lines’, and secondary and ‘filler lines’ (see Figure 4.3). She points out that this is her own terminology based on her observation of how the designs are applied17 and that the form line is the decisive element that is established first. Then parallel or secondary lines are drawn on either side of the form line, and the remaining space is filled with ‘filler lines’. She also relates that design complexity, a long form line as well as symmetry and uniformity of spacing, are highly valued and that the Shipibo-Conibo differentiate between menin, the craft side of their art work, and shinan, its creative aspect, and expect an accomplished artist to master both.

Gebhart-Sayer’s central research interest is the question of how to interpret the designs. She reports that many of the designs are named, but that these designations are purely descriptive. She sees the naming of the designs as a terminological imposition on designs that enable everyday discussions of design issues but do not reference symbolic meaning.18 She stresses the purely formal-aesthetic character of the indigenous design terminology and argues that the design tradition thrives on the invention of new forms within general stylistic parameters and is expressive of a joy in creation. She also points out that this formal-aesthetic dimension tends to get overlooked in anthropological discussions due to the discipline’s symbolic over-eagerness.

Yet despite this observation and her view that Western approaches to the discussion of indigenous art are symbolically overbearing, Gebhart- Sayer also hypothesizes that ‘the intricate design art of the Shipibo- Conibo Indians of eastern Peru may once have been a codified system of meanings’.19 She further speculates that the latter, even if ‘not a veritable writing system’, may well have ‘constituted a graphic device comprising symbolic, semantic units, in perhaps a mnemotechnical arrangement employed in ritual context’.20 Gebhart-Sayer supports this assumption with indigenous assertions that Shipibo-Conibo ‘grandparents used to know’21 about the designs. She further cites as evidence late eighteenth-century reports of indigenous design books said to have contained ciphers with graphic elements as further evidence based on the account of the Franciscan missionary Father Girbal who claimed to have seen designs with hieroglyph-like filler work assumed to operate like decipherable signs.22 She also highlights a ‘Pleiades motif’ which consists of seven crosses in evidence of an assumed formerly existing extensive astronomic complex of meaning,23 and refers to genealogic,24 cartographic25 and sexual references formerly embedded in the designs, which older women reportedly still have an inkling of.26 In further support of her semantic supposition, she refers to the work of Bruno Illius who points to the close link between song and patterned designs as part of shamanic practice.27 The assumption is that the designs could represent a musical score and hence could be part of a notation system. Musical analysis supports the assumed link of designs and song, and confirms a direct structural correlation between the patterns and the songs.28

But Gebhart-Sayer also proposes an earlier, linear mode of reading the designs in a shamanic context. The evidence she cites emerged in an interview with the shaman José Santos who, during the session, followed the meandering configurations of a design with his finger. This gesture was seen to suggest an earlier sequential, motif-by-motif reading of the designs.29 She backs up her argument about the existence of a former semantic code with pottery shards that attest that Shipibo-Conibo art goes back for more than 1,200 years.30

This view has, however, been challenged by anthropologists Deboer and Raymond. Based on close analyses of pottery shards, they argue that the Shipibo-Conibo art style emerged as late as the mid-nineteenth century around Spanish missionary stations which provided ‘suitable caldrons for […] stylistic amalgamation and innovation’31 as Indians of different cultures lived there together. This perspective poses a serious challenge to Gebhart-Sayer’s hypothesis that a semantic code once existed, because if it were of a later date, it is unlikely to have been completely forgotten in the relatively short time of a century. This begs the question how we are to understand Gebhart-Sayer’s confidence that such a semantic code once existed and whether her assumption of the existence of such a code constitutes an imposition of ‘traditional’ Western epistemologies to the Peruvian field.32

Gebhart-Sayer, as we have seen, critically reflects on what she refers to as the Western tendency of symbolic determinism. She makes a point of using the indigenous language to conduct her research in order to be closer to native modes of thought and expression, and categorically states that she is not interested in Western aesthetic analysis. She further argues that the formal-aesthetic dimension of the designs is an overlooked area of study. Yet she also states that it is a misconception to see the designs as merely decorative. For her, this is a Western misreading which she counters by emphasizing that the designs have meaning, insisting on their cultural value and significance within an indigenous cultural context. Should her insistence on the former existence of such a code hence be seen as a reaction to a Eurocentric decorative premise which devalues the designs as inferior since they do not carry meaning? In other words should we understand her semantic preoccupation as a response to the limitations of academic paradigms and Western aesthetics?

Gebhart-Sayer certainly is invested in the defence of the designs’ meaning. She is at pains to argue for an Indian-centric approach to the study of Shipibo-Conibo culture and presents the famous Shipibo-Conibo chomos, large decorated ceramic vessels, in support of the symbolic fullness of the design language (see Figures 4.1 and 4.2). The average chomo has a diameter of 70 centimetres in its widest area. Its average height is 60 centimetres, but records show unique specimens with a height of 1.50 metres. The chomo is an emotionally charged object in Shipibo-Conibo culture and many songs speak of its cultural significance. As both Gebhart-Sayer and Illius point out, the three-tiered decoration of the chomo is said to reflect the basic make-up of the Shipibo-Conibo worldview.33 The undecorated base, which is dug into the ground to give the pot stability, represents the watery underworld where dangerous spirits roam. The middle section of the chomo shows a bold lattice design and represents the terrestrial sphere of everyday life. The third section is covered in finely drawn, intricate designs that reflect the delicate patterning of higher heavenly spheres (see Figures 4.1 and 4.2).34

Gebhart-Sayer, however, warns that this cosmological scheme should be considered a basic model only. She explains that informants offer a plurality of views of how the heavenly spheres and the middle regions of everyday activity are constituted.35 She also highlights the flexibility and tolerance of Shipibo-Conibo conceptions and explains that the Shipibo-Conibo do not have a standardized system of knowledge acquisition, but that worldviews are assimilated in an informal, non-verbal, manner that is never directly instructive manner and is based on personal experience. Individuals therefore collage their own beliefs based on references picked up from conversations, songs and mythic stories. Differences in cosmic interpretations are also never explicitly discussed or investigated on a meta-level and the Shipibo-Conibo acknowledge that interpretations necessarily vary because of differing individual levels of insight. According to Gebhart-Sayer, Shipibo-Conibo culture thus acknowledges the personal nature of ‘truth’ as a matter of course.36

In the anthropological literature, this multivalence is, however, often seen as an indication of the inferiority of the cultures in question. Gebhart-Sayer critiques this view. She defends the value of Shipibo-Conibo culture and argues for an Indian-centric perspective. She holds that these differences should not be seen as a cultural lack of coherence, but should be accepted as part of Shipibo-Conibo culture. She also rejects comparative analysis of cosmologies as verificatory procedure: this for her does not do justice to an indigenous perspective. And she points out that the very fluidity and multivalence of Shipibo-Conibo conceptions has allowed for their cultural survival and enables an easy integration of ‘foreign’ elements into existing cultural frameworks.37

She further stresses that Shipibo Indians avoid simplistic explanations and consider them as indicative of a lack of mental sophistication, which they call as shina. This key term in Shipibo-Conibo culture references a whole cluster of associations linked to mind and mental activity such as ‘thinking’, ‘consciousness’, ‘creativity’ and ‘imagination’, but also signifies ‘awakeness’, a ‘good memory’ and general smartness. Further approximate translations suggested in the literature are ‘mental alertness’, ‘creative imaginative perception’ and ‘perceptive thinking’. But according to Illius, none of these translations quite captures the complexity of shina, which in Shipibo-Conibo culture subsumes ‘visionary thinking’ related to shamanic cognition and constitutes a perceptual dimension not integral to Western conceptions of mind and thought. But shina is linked to artistic activity as well as shamanic journeying because creative achievement, that is, the generation of new designs, is seen to require high levels of imagination.38 According to Gebhart-Sayer, shina enhancement needs to be recognized as the most central concern of Shipibo-Conibo life and must be taken into consideration when discussing the multivalence of Shipibo-Conibo worldviews.

In defence of her semantic hypothesis, Gebhart-Sayer draws on a further context: the geometric shapes reportedly perceived during ayahuasca hallucinations. These patterns are referred to as phosphenes or entoptic phenomena in the scientific literature and are thought to be related to the design tradition. The Brooklyn chemistry professor Dr Gerald Oster explored these and declared them a physiological phenomenon of the human body that can occur spontaneously, especially when individuals are deprived of visual stimulation for a length of time. According to Oster, inner perceptions of geometric patterns can be induced by rubbing one’s eyeballs, through the ingestion of drugs or through electrical stimulation in a lab setting. These ‘subjective images, independent of an external light source’39 were thought to ‘reflect the neural organization of the visual pathway’ and seen to ‘provide a means of studying the exquisite functional organization of the brain’.40 And as these shapes are thought to ‘originate within the eye and brain’ they were declared ‘a perceptual phenomenon common to all mankind’.41

Based on this scientific theory, the anthropologist Reichel-Dolmatoff argued a close correlation between phosphenes identified in lab settings and indigenous design motifs of the Tukano and Desana Indians of the Amazon lowlands (see Figure 4.4).42 For him these entoptic perceptions constitute elementary forms that have provided artistic inspiration across time, and explain the widespread use of similar motifs in ‘petroglyphs and pictographs of the region and areas far beyond it’.43 His linking of phosphene theory to Amazon design languages launched a new departure in discussions of Amazon art. Gebhart-Sayer, for example, declared that the designs perceived during shamanic visions of the Desana Indians, as described by Reichel-Dolmatoff,44 ‘coincide in all aspects with descriptions of Shipibo-Conibo visionary experience. Hence we may assume that the graphic perceptions are a phosphenic retina function triggered by the alkaloids of the drug.’45

The phosphene hypothesis had far-reaching implications. As these shapes were considered to be reflective of human physiology rather than true visual experiences, researchers concluded that the reported shamanic perceptions of geometric shapes by Amazon Indians constitute a cultural overlay over a biological phenomenon. Indigenous descriptions of these experiences as communications with the spirit world were subsequently considered cultural (mis)interpretation of organic occurrences and seen as proof of Indian naiveté.46

This view generated a paradoxical situation. Anthropologists on the one hand gathered detailed considerations of all aspects of Amazon design culture, from the preparation of clays and glazes to various hypotheses on the meaning of the designs, and diligently recorded shamanic beliefs, detailing descriptions of shamanic sessions, visions, cosmologies, conceptualizations of nature spirits and trance experiences. Yet, due to the consensus that the origin of the design cultures lay in patterned retinal reactions to hallucinogenic drugs, the perceptual worlds of Amazon indigenous cultures were on the whole not considered as subjects of anthropological exploration.

Phosphene theory also shifted the issue of the lost semantic code. As indigenous visual culture was now seen to be rooted in misguided cultural interpretations of phosphene phenomena, their visual worlds were thought to signal an image-based rather than abstract mode of cognition considered a lower level of cultural development. For example Gebhart-Sayer frames indigenous figurative thinking such as shamanic interpretations of ‘retinal experiences’ as metaphorical cognitive modes, which relate images to experiences by analogic processes representative of non-discursive modes of thought. This pictorial modus operandi was declared a typically Indian way of reducing sensual overload by creating coherence and hence meaning, and seen as fundamentally different from causal Western cognitive modes.47 The reported experiences and visions during shamanic trances were subsequently framed as visualization processes that integrate religious and medical ideas and are translated via psychoactive stimulation into sensory and emotionally available forms.48 This understanding also explained the central place of pattern art in Amazon culture. Designs were agreed to suffer from ‘semantic depletion’ but were also acknowledged to signify tribal identity in a non-specific, overall manner. Further concepts seen to inhere in Shipibo-Conibo designs, much like the art of the neighbouring peoples, were the contrast between the wild and the cultivated and the difference between one’s own ethnicity and the identity of other Indians.

The designs were thus seen to play a central integrative and emotional role in the symbolization of core cultural values. They were argued to provide transformational, associative channels of meaning able to bridge the underlying dualism of the often threatening visible and invisible realms of force that Shipibo-Conibo Indians are required to negotiate in their daily lives. The Shipibo-Conibo world was thus framed as categorically different from Western culture and the Indians were seen to live in a dangerous world of chaotic force they can only master through the illusion of order and control that the designs offer. Unlike Western culture, Amazon Indians were thought to have no real control over nature and this ‘vulnerability’ was seen to signal their civilizational inferiority.

Phosphene theory therefore led to Gebhart-Sayer’s positing of an indigenous pictorial mode of thinking that works in an analogue rather than a semiotic manner. However, when thought through, this hypothesis constitutes a counter argument to her proposition of the former existence of a semantic way of reading the designs: if there was an earlier sequential reading of the designs that now has been replaced by a pictorial mode of cognition, would this not indicate a fundamental shift in the indigenous mode of existence (which seems unlikely)? Or did both modes exist in parallel and only one has survived to the present?

Gebhart-Sayer’s conviction that the designs can be read in a semantic manner hinge on a further context that she presents: an aesthetic-therapeutic application of patterns rooted in the shamanic practice of ayahuasca trance. According to her informants, the presence of disease is revealed to the shaman by ‘bad’ or partially erased designs in the patient’s body that are visible to the shaman with his ‘ayahuasca eyes’. Replacing the harmful or broken design pattern in the patient’s body with ‘good’ designs is key to the healing process. If the procedure is successful, the patient will recover from the illness. But if the new designs do not hold even after repeated treatments, the shaman will not be able to help the patient.49

According to the anthropological literature, the shaman receives the invisible designs he uses in the healing sessions from his spirit helpers who ‘project luminescent geometric figures’ visible only to the shaman. It is the task of the shaman to interpret the designs as they flash up against the night sky. The shapes are described as pulsing, floating, undulating, shining and fragrant patterns that are said to cover ‘everything within the shaman’s sight’.50 According to Gebhart-Sayer, the shaman also translates the designs into song and the ‘songs are simultaneously seen, heard and sung by the ayahuasca master spirit, the other attending spirits and the shaman’,51 while for the villagers only the voice of the shaman is audible. Songs are sung in quick succession during the entire length of the session and the shaman must follow the songs of the spirits he hears (or sees)52 as closely as possible not to lose their therapeutic power. Gebhart-Sayer also informs us that when the shaman moves from diagnosis to treatment, a further transformation occurs. Now the shaman’s design song ‘assumes the form of a geometric pattern’ with the designs ‘penetrating the patient’s body and settling down permanently’53 if the session is successful.

It is this reported shamanic design therapy that lies at the heart of Gebhart-Sayer’s conviction that the designs can be ‘read’. She, like most of the anthropological community at the time, interpreted this reference to readability in terms of an iconographic mode of reading the designs. The news of the design therapy electrified the scholarly community who redoubled their efforts to ‘crack the code’ which clearly seemed to exist, as shamans were able to read the messages inherent in visionary designs. The mystique at the root of the Shipibo-Conibo art style further grabbed the popular imagination and fuelled a wave of tourism to the Amazon. Yet despite these concerted efforts, no further details about a semantic reading of the designs could be ascertained and, over time, anthropological interest in Shipibo-Conibo designs waned.

More recently, however, the anthropologist Bernd Brabec de Mori – who married a Shipibo woman he met in the field – took up the issue again. His insider status gave him access to information not otherwise available. He revealed Shipibo-Conibo aesthetic therapy as a story invented by the Indians to ‘present a “more interesting” medicine to the visitors by merging art, music and plant drugs’54 that was eagerly taken up by the researchers passing through their villages. He furthermore argues that ayahuasca appeared only relatively recently in the Shipibo-Conibo community, probably some time between 1865 and 1925, which discredits the hypothesis of a long-standing Shipibo-Conibo design tradition and the existence of a long-forgotten semantic code rooted in ayahuasca visions. He also reports that taking ayahuasca was initially a marginal pursuit by shamans, kept at arm’s length by the Shipibo-Conibo community.

However, this changed with the arrival of Western scholars, ‘among them Michael Harner and Terence and Dennis McKenna’,55 keen to explore ‘ayahuasca shamanism’. This gringo enthusiasm gave shamans a great deal of prestige in their communities and spurred a wave of interest in ‘training and administering the brew in order to attract the many drug tourists and young researchers who followed’.56 He also relates that Gebhart-Sayer’s hypothesis of an aesthetic design therapy was absorbed with great interest, not just by Western scholars and drug tourists but also by ‘young Shipibo women and men who heard of the hypothesis through the author herself’57 or deduced it through the questions asked by the next wave of ‘researchers and tourists who had read Gebhart-Sayer’s book’.58 According to Brabec, the Shipibo-Conibo continue to perpetuate this theory as advertisement for their art even though they know and readily admit within their own circles that it is fabricated. Brabec also reports that in keeping with the theory, many shamans now literally cover their patients with designs by placing patterned indigenous textiles over them during shamanic sessions. Yet, according to him, they concede in private that the medical efficacy of this design therapy is dubious.

He also reports that this theory, which emerged through the anthropological encounter of Western researchers and the indigenous population, is now shaping a new tradition. As Brabec informs us it ‘slowly but steadily transforms into reality, because corresponding “healing sessions” or “shamanic ceremonies” are held with growing frequency and social impact’ and are adopted especially by ‘culturally less educated (mostly urban) Shipibo today’59 as historical truth. But if ‘aesthetic therapy’ is fallacious, along with the associated claim that the designs can be read by the shaman and hence be understood and decoded, where does this leave the question of how to read the designs? Can the link between the designs and shamanic practice be sustained even if the pattern-based therapeutic theory is not feasible?

Discussions of the pattern art of neighbouring tribes with related shamanic practices and design traditions will be explored in what follows to address these questions. The literature reveals that anthropologists working on related material cultures equally link the pattern art they encounter to shamanic perceptions but stop short of arguing for a medicinal connection. The anthropologist Peter Gow, for instance, writes about the neighbouring Piro Indians and points out that the Piro design system has clear ‘affinities with those of the Shipibo-Conibo people’.60 He reports that the Indians in the region agree that the Piro make beautiful designs but that they think the work of the Shipibo-Conibo to be superior to Piro art due to the greater complexity and sophistication of the designs.61 Gow also links Piro designs to hallucinogenic trance visions but makes a case for an indigenous, image-based way of making sense of the world that differs from Gebhart-Sayer’s propositions. In his article ‘Could Sangama Read?’62 Gow interprets a story about Sangama, the first Piro who reportedly could read, which for Gow offers a key to the question of how to read indigenous designs. The story was recorded by the missionary Esther Matteson and was recounted around 1948 by the Piro Moran Zumaeta, one of the first literate Piro and bilingual school teachers. The events of this story occurred between 1912 and 1920. It relates how a Piro called Sangama taught Zumaeta to read. Sangama claimed to have ‘learnt to read in school’, an unlikely claim since it was not common at that time to educate Indians. According to Zumaeta, Sangama demonstrated his reading skills by holding a newspaper in the manner of a ‘white man’ but described it as a woman with red lips speaking to him. When Zumaeta protested that he could not see a woman but only a newspaper, Sangama insisted that she was there, that speaking to her is the way to read a newspaper. He explained:

When the white, our patron, sees a paper, he holds it up all day long, and she talks to him. She converses with him all day long. The white does that every day. Therefore I also, just a little bit, when I went downriver a long time ago to Para […] I was taught there. I entered a […] school. […] A teacher sent for me. That’s how I know.63

Highlighting the unlikelihood of anyone teaching Peruvian Indians to read at this time, Gow draws attention to Sangama’s description of how he read: talking to a woman with painted lips. He comments that ‘the most remarkable features of Sangama’s account of reading, at least for a Western person, is that he does not treat the graphic components of writing as “representations” or “symbols” of words’.64 The story rather spells out that Sangama experiences the newspaper ‘directly as a person who speaks’.65 For Gow this non-representational approach can be explained by Sangama’s transference of metaphors drawn from shamanic practice. He points out that ayahuasca, the hallucinogenic drug that induces shamanic visions, is frequently referred to as the body of ‘ayahuasca mama’, and that Sangama’s claim that his eyes are ‘not like theirs’ are a reference to seeing ‘through the eyes of ayahuasca’ 66 Gow further explains that the ‘onset of ayahuasca hallucinations is marked by the appearance of rapidly shifting fields of brightly coloured designs’,67 whereas when the trance is at its height, figurative visions prevail.68

For Gow, this transformation of geometric designs to full-bodied visions provides the framework for the indigenous approach to ‘writing’. He argues that from a Piro perspective, the covering of surfaces with motifs is invariably understood as a mere preliminary stage to an embodied spirit who directly addresses the trancing drinker.69 Gow therefore interprets the story of Sangama as a shamanic approach to reading envisioned as ‘a transformation of paper, from a surface covered with “design” into a corporeal woman who speaks to him and reveals information’.70 He points to a fundamental difference between Western and Amazon Indian modes of referencing knowledge: whereas in the West, writing encodes speech represented by an alphabetical code which composes words and meanings in an additive mode, in the Indian context, those who know how to ‘read’ have the ‘eyes’ which allow them to see the printed page as the woman with the painted mouth and are able to converse with her. Or, as Gow puts it, ‘the paper is the manifestation of a woman who bears messages’.71

Based on this understanding of the fundamental difference between approaches to modes of ‘reading’, Gow is not surprised that a semantic- iconographic approach to Shipibo-Conibo, Piro and other indigenous design languages in the region has not delivered results. For Gow, the designs are not concerned with representational or semantic content but with the visual control of surfaces. The surface for him is thus not merely a substrate for graphic elements that are the main signifiers, but constitutes an important design element in its own right. He argues that the successful adaptation of a design to a complex surface is considered the source of its beauty, while failing to integrate the design and surface is considered ‘ugly’. For him the designs therefore signify the power to transform, which in his view explains why individual design elements hold no interest for the Piro. And as Ucayali art,72 according to Gow, emphasizes the status of the painted surface, the Indians locate the power of writing not in the individual characters, but in the material they are inscribed on: the book or the paper. Ultimately therefore for Gow a mutual misunderstanding is playing out with regard to how designs or graphic elements placed on surfaces signify. He states that

while Westerners have searched the graphic component of Ucayali art in the vain pursuit of a semantic key, the Ucayali people chose the other pole of the relationship […] and searched the plastic component of European writing for an explanation of its power […]73

For Gow, the question of the semantic code therefore represents a projection of Western cultural assumptions onto Ucayali art, while the Indians in turn transpose their transformative approach to designs to the act of reading the newspaper.

This observation introduces a new perspective to the discussion of the designs. It highlights the anthropological premise of cultural translatability and brings the issue of cultural mistranslation into view, which for Gow explains a key aspect of the difficulty of making sense of Ucayali art. His interpretation thus draws attention to the fact that translative encounters are fraught with difficulties and generate misunderstandings. Areas that culturally do not signify are also frequently glossed over in such encounters and reflect the limitations of prevalent preconceptions, circumstances that need to be reckoned with in informed intercultural encounters.

Cultural Translation’s Double-Coded Third

Gow, despite raising this important issue, limits this observation to his work on Piro designs and does not reflect on the conditions of cultural translation for anthropological enquiry. The cultural theorist Sarat Maharaj, however, has examined the conditions of cultural translation in great detail. He asks us to recognize the existence of the ‘untranslatable’ or inevitable residue of translation and wonders whether it can be voiced at all, and if so how ‘the leftover inexpressibles of translation’74 can be articulated. Yet for Maharaj the recognition of translation’s predicaments and limitations does not absolve us from the arduous work of translation. He points out that South Africa’s apartheid regime adopted a perspective of ‘untranslatability’ and ‘projected the impossibility of translation, of transparency, to argue that self and other could never translate into or know each other’.75 This in turn led to the institutionalization of ‘a radical sense of ethnic and cultural difference and separateness’.76

But while apartheid with its insistence on separate ‘pure’ spaces constitutes an extreme manifestation of cultural difference as untranslatability, for the artist and cultural critic Rasheed Araeen, multiculturalism harbours similar dangers as it also emphasizes separateness and difference at the expense of a cultural rapprochement. As Araeen explains, the ‘creation of a separate ethnic minority arts category has created cultural bantustans, a cultural apartheid, and has harmful effects as it does not integrate these cultures’.77 Araeen thus holds this limiting understanding of multiculturalism responsible for the marginalization of debates around cultural difference, which disavows the relevance of marginal cultures for the mainstream. He is also highly critical of the creation of separate and special realms for ‘alterity’ in the art world, which in his view need to be plunged into translation.

These reflections on the conditions of cultural encounter, difference and translation offer a new perspective on Gebhart-Sayer’s insistence on a semantic reading of the designs. The question now arises whether this hypothesis needs to be recognized as an effort in cultural translation rather than a projection of Eurocentric perceptions, however problematic her hypothesis of a semantic way to read the designs may be. In other words, should we credit Gebhart-Sayer’s semantic proposition presented in the face of the claimed fundamental difference of Indian modes of cognition as a limited but nonetheless venerable effort to engage in translation and hence make a relational effort rather than posit the designs as indicative of untranslatable difference?

Maharaj offers further insights here as for him acts of cultural translation not only leave ‘residues’ but also carve out double-coded space in-between cultures. He emphasizes that there is creativity at play when different languages, systems of thought, and manners of meaning meet in translation. For him the translative encounter ‘cooks up’ a third, a hybrid in-between, as ‘the construction of meaning in one does not square with that of another’.78 But according to Maharaj, this newly created ‘in-between’ not only constitutes a creative fashioning in response to the differences to be bridged, but also represents translation’s failure, ‘something that falls short of the dream-ideal of translation as a “transparent” passage from one idiom to another, from self to other’.79 For Maharaj it is translation’s tension, its double-coding, which needs to be conceptually acknowledged and maintained, a process that requires ‘safe-guarding its volatile tension, its force as a double-voicing concept’.80

Seen from this perspective, Gebhart-Sayer’s report of a Shipibo-Conibo ‘aesthetic therapy’ that emerged from the encounter between Western researchers and Shipibo-Conibo Indians no longer registers as a cultural fabrication or make-belief, but can now be seen to demonstrate the creative potential and failure of cultural encounters representative of cultural translation’s double-coded ‘third’. The invention of ‘aesthetic therapy,’ furthermore, needs to be recognized as an act of empowerment on the part of the indigenous peoples who actively participated in fashioning these stories and thus turned the curiosity of the anthropologists and other ‘gringos’ who traipsed through the jungle to their advantage. Such participatory cultural fashionings and the empowerment they represent constitute an important, frequently encountered aspect of translative encounters. There are, for example, many reports of how eagerly and actively Indians absorbed the anthropological material penned on the basis of the information they themselves had provided. Antonio Guzman, the informant of the prominent anthropologist Reichel-Dolmatoff, thus not only attentively studied the anthropological literature on Amazon cultures, but is also reported to have given seminars in anthropology.81 In a similar vein Bruno Illius reports that the Shipibo-Conibo community he worked with took a keen interest in his texts and that he had his publications translated into Spanish for the Indians to read and approve, thus acknowledging their role as co-producers. He also relates how eagerly they embraced his framing of their worldview on the basis of the chomo which they in turn used to explain their art in the 2002 exhibition in Lima Una Ventana hacia el Infinito. Arte Shipibo-Conibo (A Window to Infinity. The Art of the Shipibo-Conibo).82

The question of how to read Shipibo-Conibo designs therefore needs to take the phenomenon of cultural translation into account and reflect on how the fieldwork situation and the conceptual frameworks that engage in such encounters interact and inflect the knowledges that are created. It must also be noted that the recognition of translation’s misadventures does not absolve culture-crossing travellers and researchers from continuing with translative efforts as they may yet yield more appropriate results. If one were, for example, to acknowledge Gebhart-Sayer’s insistence on a semantic reading of Shipibo-Conibo designs as an effort in translation that demonstrates the limitations of the conceptual frameworks engaged and hence speaks to the thorniness of such translative endeavours, this recognition does not limit the field. Quite the contrary: it invites further translative perspectives as such accounts are now no longer understood as veridic statements that resolve questions or represent cultures ‘once and for all’, but as translative approximations that will inevitably be partial and flawed, even if high levels of translative rapprochement have been achieved. Anthropologist Barbara Keifenheim, whose work adds an important further dimension to the discussion of how to read Shipibo-Conibo designs, is a case in point. Based on her work on the Cashinahua Indians in Eastern Peru, she developed an alternative perspective on Amazon Indian pattern art that foregrounds affectivity and performativity, a perspective obscured by the prevalent iconographic approach.

The Cashinahua have a distinctive design tradition that, similar to the Shipibo-Conibo, is an exclusively female affair. Women are held in high esteem for their patterns but the designs are less complex than those of Shipibo-Conibo art. They mainly consist of a small number of basic motifs composed according to a limited number of rules. She cites meandering hooks (or geometric curls), rhombi, triangles, squares, wavy lines and zigzags as core motifs, and underscores the negative–positive principle as a fundamental compositional principle (see Figure 4.5).83 A further characteristic of Cashinahua designs is that they often show a seamless transition between patterns.

Keifenheim disagrees with Gow’s proposition that Piro designs and, by implication, Amazon pattern art are concerned with the visual control of surfaces. She holds that they rather are ‘surface-surpassing’ in a manner which ‘opens perception to a larger space’ suggestive of a ‘continuity beyond the limits of the decorated material’.84 She also emphasizes visual transformation as key to the ‘shifting pictorial continuum’ of Cashinahua art, and sees ‘visual ambiguity’ as characteristic of Amazon designs in general. For her, this reflects the indigenous sense that exterior and interior states are interlinked.85 She also refers to David Guss’s description of the pattern art of the Yekuana Indians of Venezuela as ‘kinetic visual process’,86 and argues that Amazon pattern art not only makes statements about the multi-modal nature of perception, but importantly also performs this reality.

According to Keifenheim, the patterns induce a border-transgressing experience in the perceiver through bodily-sensual perceptions87 that echo drug-induced visions. For her any attempt to unravel the designs’ meaning by seeking to decode the motifs is therefore misguided. She argues that the meaning of the designs ‘becomes manifest in the experience of visual transformation connected with the viewing of the ornamental pattern’, and declares that ‘in ornamental visual experience viewer and image are equally subject to the same transformation principle’.88 Keifenheim therefore sees Cashinahua pattern art as expressive of a perceptual world that encompasses shamanic vision and generates meaning through a transformative visual experience produced by an attentive viewing of shifting ornamental designs. She argues that ‘culturally specific concepts such as transformation’ are ‘not semantically revealed’ but are experienced ‘in transformative sensorial experience’,89 which she sees as a key element of ornamental pattern art that has so far been overlooked. She stresses that when viewing Amazon ornamental art, ‘significance must be understood as something which always emerges new and not as a corpus of fixed symbols’.90 The meaning of the designs is therefore dependent on and develops in relation to the ‘context, expectation, personal conditioning, sex, age’91 and so forth of the perceiving subject. She points out that in Cashinahua art, perceiving and granting meaning are closely intertwined and that the designs should be recognized as a ‘processual play of cognitive and imaginative capabilities’ that unite the ‘sensual and the intelligible’92 in a manner that allows each viewer to reconstruct and re-enact this understanding according to his or her level of cognizance.

Keifenheim proposes a switch to a performative perspective, which places the body at the centre of a sensate negotiation of the world. She argues that this line of enquiry is more productive than the ‘iconographic search for traces for semantic meaning’93 which has characterized the investigation of Amazon art. She proposes to adopt a performative approach based on ‘native vision theorems’ to make sense of the designs, and argues that this allows for the articulation of a new paradigm of ‘ornamental visual experience,’94 which she refers to as a ‘theory of ornamentalistics’.95 She declares that when such a performative perspective is adopted, the image and its beholder are, ‘even if only for a fleeting moment’,96 in a co-constitutive and transformative relationship characterized by affectivity. She also points out that if such a process is repeatable, it can be shared communally and generate a sense of connectedness or conviviality.97 Keifenheim therefore links the performativity and affectivity of the art language to a sense of community created by the shared perceptual experience of the designs that reinforces central cultural concerns. Keifenheim’s interpretation furthermore acknowledges that indigenous notions of perception based on trance experiences do not separate the worlds that are ordinarily visible to the human eye from the ones that are invisible to everyday vision. She therefore does not reject the idea of shamanic visions on the grounds of phosphene theory but rather leaves the question of veracity aside and engages with shamanic vision as a cultural phenomenon. She explains that for the Cashinahua, the visible and the invisible are not opposed but are considered ‘shifting transformational appearances of one and the same reality’.98 She furthermore reports that the Cashinahua consider the perceiver to be energetically permeable and ‘subjected to the perceiving non-perceivable’, that is, the viewer’s ‘human sensory instrumentarium not only opens the world to him but also allows the perceived world to penetrate him’.99

As the anthropologist Els Lagrou reports, the Cashinahua focus ideas of similarity and difference on the body. The body is, however, not seen as a bounded entity that develops along its genetically preprogrammed path, but rather is ‘modelled by others through conviviality and the sharing of thoughts and substances with those one lives with or encounters when travelling’.100 In a similar vein the communal is thought of in terms of a collectively shaped body that people belong to ‘as a result of the experiences, memories, food and bodily substances that have been exchanged and shared among them’.101 This interlinking of consumption and the convivial introduces an interesting parallel to Tiravanija’s trademark sharing of food with gallery goers, especially as cooking plays a key role in the Cashinahua act of communal ‘body-shaping’ where rites of passage are conceptualized in terms of bodily transformation.102 The permeability of Cashinahua subjects and environments, furthermore, corresponds to Guattari’s ethico-aesthetic conception of subjectivity that stresses the porousness of an individual’s boundaries seen to enable human participation in environments and collectivities. These connectivities range from ‘pre-personal, polyphonic, collective and machinic’103 elements representative of non-discursive intensities that exist in parallel to the logic of discursive sets to larger social and environmental territories. Indigenous notions of permeability and affective assimilation linked to conviviality and consumption, however, are not limited to the Cashinahua but constitute a common conception in Amazon culture and underscore the relevance of this observation and linking of pattern art, Amazon sociality and the communal consumption of food.

Keifenheim’s proposition of an indigenous ornamental perceptual experience that operates via the affective introduces a crucial further element to the question of how to read Shipibo-Conibo and, by implication, Amazon pattern art: the designs’ community-building potential due to their transformative, affective charge. This approach shifts the discussion from the search for a semantic code to the designs’ perceptual affectivity. And while Shipibo-Conibo patterns on the whole do not show seamless transitions between patterns like Cashinahua art, they do consist of positive–negative shapes, and can therefore be said to encompass related performative and affective dimensions that signal the fluidity and co-existence of visible and invisible worlds and make this reality perceptually available.

Keifenheim, who uniquely draws out the link between Amazon pattern art and notions of conviviality, is not the only scholar to posit communal values and affectivity as integral to Amazon cultural worlds. The anthropologists Joanna Overing and Alan Passes argue that life in the Amazon region revolves around an ‘aesthetics of community’104 linked to the affective which the authors explore in great depth and are at pains to defend against the charges of primitivity levelled in the past. Their findings offer important insights into indigenous conceptions of the convivial relevant to the proposed translative exercise of expanding a post-Bourriaudean relational aesthetics into the realm of Amazon culture, and will be summarized in what follows.

Overing and Passes point out that the conviviality at the heart of indigenous life in the Amazon has long been overlooked because paradigms of Western social thought are projected onto the cultures studied. They highlight that such Western ‘notions as society, culture, community and the individual’105 inhere in ‘Western distinctions of judgement and worth’106 which in turn inform ‘the very analytic constructs through which they [Western scholars] then gazed at, assessed and recorded all other types of socialities’.107 Overing and Passes also report that Amazon social life, like indigenous design languages, has for a long time remained obscure since ‘the nature of indigenous sociality in Amazonia has always been resistant, rebellious even, to most anthropological categorisation’.108 The authors delineate how Western notions of the social – premised on a separation of public and private – the rational space of societal relations and the domestic space of the personal, along with conceptions of a hierarchically structured public space ruled through political coercion – failed to see any sociality in indigenous cultures of the Amazon region and condemned them as ‘primitive’. Only when challenges to this theoretical construct were mounted from within Western academia, often from feminist quarters, and a new, positive emphasis on the everyday, the domestic and a sociality of affectivity was theorized did the contours of Amazon sociality become visible.

The authors thus argue that if ‘intellectual decolonization’ is the aim, we cannot limit our understanding of the social to kinship relations, ‘or to such equally reductive principles as exchange, reciprocity and hierarchy’.109 What needs to be acknowledged and explored instead is the indigenous ‘aesthetics of living’, their stress on and need for beauty in the everyday and ‘their strong sense of the follies of existence, its myriad of interconnections with an animated universe, its ambiguities and dangers and its possibilities for beauty’.110

Overing and Passes explain that they consider the term ‘conviviality’ best suited to express indigenous conceptions of the social because it ‘seems best to fit the Amazonian stress upon the affective side of sociality’.111 But they also warn that the ‘rich language of affect and intimacy that is linked to Amazonian sociality is not to be mistaken for evidence of a prioritising of emotions over reason’.112 They hold that this would not only be erroneous but also that it plays into well-rehearsed notions about the pre-logical nature of so-called primitive societies. Overing and Passes rather point out that Amerindians ‘consider not only that both cognitive and affective capacities are embodied, but also that, for them, the capability to live a moral, social existence requires that there be no split between thoughts and feelings, mind and body’.113 The authors therefore emphasize that in Amazon culture ‘there is an aesthetics involved in belonging to a community of relations that conjoins body, thought and affect’.114

This Amazon version of an aesthetics of relation conjures up Bourriaud’s articulation of relational aesthetics and returns us to our question of whether an expanded notion of relational aesthetics can be helpful in the present effort of cultural translation focused on the question of how to read Shipibo-Conibo designs. But is it an all too easy and quick assumption that Amazon notions of the convivial can be related to the conviviality generated in the gallery spaces of the post-industrialized world? Bourriaud, for example, neither emphasizes the body nor reflects on affectivity and thought in relation to community. This concern, while perfectly justified, nonetheless overlooks the transformative effect of encounter which also applies to the conceptual realm. The argument presented here, rather, is that the proposed expanded notion of relational aesthetics can tease out the affectivity inherent in Bourriaud’s Guattarean borrowings, which the former did not acknowledge, and that the transposition of relational aesthetics into the worlds of Amazon art constitutes an opportunity to probe and to re-envision Bourriaud’s aesthetic framework.

Relational Aesthetics the Amazon Way

Unlike relational aesthetics in its Bourriaudean form, the indigenous worldview stresses the need to transform the destructive and dangerous inner-personal and cosmic forces that continually threaten the fragile state of the convivial. It emphasizes that effort is required to maintain the delicate state of harmonious, affective social relations since ‘matters of affect require constant work, vigilance, and even suffering to maintain’.115 Unlike relational aesthetics’ assumption of an easy attainment of convivial states as bodies co-mingle in a gallery space – which, as we have seen, has drawn fierce criticism and has been deemed naive – in the Amazon the maintenance of the convivial requires sustained application. It constitutes a form of social art that hence offers a corrective to Bourriaud’s notion of relationality ‘light’.

Overing and Passes furthermore relate that ‘Amazonian sociality cannot be understood without the backdrop of the wider cosmic and intercommunity and intertribal relationships’116 and remind us that the ‘forces of conflict, violence, danger, cannibalism, warfare, and predation’117 are the paradoxical ‘other’ that need to be tamed and transformed. The Amazon understanding of the convivial, therefore, can ‘only be achieved through the suffering and hardship of enduring a multiplicity of difficult, treacherous paths that eventually enable a person to transform the violent, angry, ugly, capricious forces of the universe into constructive, beautiful knowledge and capacities’.118 Living harmoniously in the Amazon region thus is an ‘artful skill’119 and the creation of a beautiful, good life and ‘intimate, informal relationships of the everyday’120 are ‘the primary concern of most Amazonian peoples’.121

Overing and Passes also report that in indigenous communities, such balancing acts ‘seem to take up most of their time and energy’.122 This observation returns us yet again to Amazon designs and their positive–negative shapes. As we have seen, Keifenheim argues that the transformative perceptual experiences generated by Cashinahua designs provide a sensate, embodied understanding of the ambivalence of life, the delicate balance between positive and negative forces that needs to be continually maintained, and of the beauty that results if such an equilibrium is achieved. For her this constitutes the meaning of the designs. This, however, only becomes apparent when the art style is examined from within an indigenous context of cosmology and sociality, that is, when Western conceptions of the visual and the social are suspended. But leaving Western perspectives aside is not an easy affair as the very conceptions used to discuss such cultural contexts are informed by Western constructs which often negate the validity of the cultural worlds under discussion or simply cannot register them.

So where do these insights leave our question of how to read Shipibo- Conibo designs, and what role could an expanded notion of relational aesthetics play to bridge the worlds of art, anthropology and of the Amazon region? As we have seen, a key issue to be negotiated is the translation of the dualism of Amazon worldviews and their inherent non-discursivity into traditional Western paradigms that are based on a mind–body split and consider indigenous notions of a mind–body continuum as naive and inferior. Encounters governed by this Western premise therefore are not conceptually neutral, curious and open to translation, and furthermore are governed by power relations skewed in favour of the West. A switch to conceptual paradigms more conducive to this translative encounter consequently cannot altogether undo existing power differentials, but can open the way to more equitable meetings that dispense with charges of primitivity and inferiority.

The suggestion is that the double-codedness of Deleuze–Guattarean machinism, its Janus-faced connectivity of discursive and non-discursive registers and the ‘relation of alterity’123 inherent in the proposed expanded version of relational aesthetics, offers a productive conceptual terrain for the intercultural encounter with Amazon cultures. It brings the hand of the shaman José Santos to mind as it moves horizontally across the designs anthropologists inquire about. This simple gesture is laden with meaning, certainly in the minds of the anthropologists, who saw it as indicative of a linear reading of the designs similar to the act of reading a text. Arguably the anthropologist as representative of an academic, institutionalized mode of knowing is used to the homogenizing ways of the signifier, which his or her discipline demands, and is seeking for the familiar in Shipibo aesthetic culture. Furthermore, the possibility of a-signifying modes of ‘reading’ the designs are difficult to grasp, especially without a framework that can register such perspectives. Deleuze–Guattarean conceptions, however, cater to such conceptual possibilities as they harbour the potential to encompasses a-discursivity.

As we have seen, the designs’ persistent rebuttal of semiotic advances is interpreted as refusal to reveal their secrets or as contemporaneously defunct symbolism in the anthropological literature. But from a machinic perspective the lamented muteness of the designs can now be read as reference to machinism as ‘other’ mode. This shift in perspective allows the quest for a semantic code to be interpreted as a battle over modes of being, that is, a struggle between signifier and machine. Anthropologists like Gebhart-Sayer thus no longer need to tie themselves into translative knots to defend Amazon pattern art against pejorative classifications of mere decorativeness by embarking on an obsessive search for semantic content to prove their inherent cultural value as thought along Western lines. Non-discursivity as alterior mode of cognizance now no longer invariably computes as the lesser world of analogue pictorialism, nor are indigenous references to negotiations of force and to notions of dualism inevitably reduced to markers of primitive naiveté. Moreover, machinism, or to be more precise, aesthetic machinism, encompasses an emphasis on affectivity and sensation. It thus harbours the potential to mediate Amazon cultures and to register non-discursivity and affectivity as a differenced perspective that operates ‘not through representation but through affective contamination’.124

But this translative encounter also launches aesthetic machinism, conceived as an antidote to the ‘steam-roller of capitalistic subjectivity’,125 into a new adventure. For Guattari, its differenced generation of alterity constitutes a mode of liberation, which expropriates scientific paradigms, a battle Amazon cultures are not concerned with unless they engage with researchers that seek to interpret their art and culture. Aesthetic machinism which draws out ‘intensive, a-temporal, a-spatial, a-signifying dimensions from the semiotic net of quotidianity’126 representative of a ‘chaosmotic plunge into the materials of sensation’127 will hence be challenged to engage with Amazon conceptions.

The proposed expanded notion of relational aesthetics which encompasses Deleuze–Guattarean machinism therefore arguably can offer a bridging moment between Western systems of thought, contemporary art and the cultural worlds of the Amazon as it allows key cultural constructs, such as transformative visions, affectivity and the convivial, to register. The adoption of a relational Deleuze–Guattarean framework for a translative rapprochement between indigenous art, anthropologists and the world of contemporary art thus potentially allows for translative acts that leave a smaller untranslatable residue and ‘cook up a third’ that, while inevitably double-coded and shot through with creativity and failure, may situate these poles at a lesser distance. The proposed ‘post-Bourriaudean’ notion of relational aesthetics also engages the original Guattarean notion of the transformative potential of the ‘proto-aesthetic’ and thus comfortably transgresses the spaces of the gallery. It unearths and develops untapped potentialities of Bourriaudean relational aesthetics as it teases out Guattarean notions of performativity and affectivity through the encounter with Amazon culture, and thus offers a yet unbroached potential to mediate the worlds of art and Amazon designs.