The account of Creation summarized in Chapter 2 highlights a fundamental principle of pharaonic belief, which the Egyptians termed ‘Truth’. We have seen Sety I offering Truth to Osiris as ‘the Lord of Truth’ (see pp. 16–17). Before 2300 BC Ptahhatp, vizier of Egypt and the world’s earliest known philosopher, was teaching that ‘the essence of Truth is its constancy’ and that ‘a person grows by accepting Truth’. In his account, Truth is the principle that the world exists because it is intended, and has form and meaning as a result: form, because it is not randomly happening; meaning, because it is here for a reason. How else could we ask questions? Because the world is Truth-full, so the elemental principles include not only laws of physics but also mathematics, aesthetics, justice and so on. If we appreciate beauty, sport or poetry, then we are responding to the elements of Creation, according to this point of view. As Ptahhatp urges, ‘find the meaning for yourself in every event until your conduct becomes exemplary’.

24 View of the principal temples against the Theban hills at Deir el-Bahri, illustrating the ramps and terraces that stand at one end of festival procession routes. The 18th Dynasty temple of Hatshepsut is in the foreground, the earlier mortuary temple and tomb of Montuhotep II prominent behind it. West Thebes.

In keeping with the belief that things do not ‘just happen’, the original locations of many ancient Egyptian sacred sites seem to have been determined on the basis of meaningful features in the landscape, to which builders over time simply added a refined architectural form. Certainly, like the temple of Horus at Hieraconpolis, several early temples developed on the site of natural mounds of various kinds, while the famous Great Sphinx at Giza is one of several prominent monuments carved out of a distinctive natural outcrop. The interplay is such that many temple sites seem to grow naturally out of the landscape, and the architects’ respect for the natural setting is obvious [24]. Nonetheless, the issue of origins almost always has to be inferred because the sites of most temples have been so thoroughly developed and redeveloped, then disturbed, in ancient as well as modern times. On the other hand, we can be certain that mathematics was intentionally employed to determine the appropriate forms of temples and, in religious terms, acknowledge and praise a higher authority. Evidently this is a principal reason for the significance the ancient Egyptians attached to ideal geometric shapes in architecture, including, of course, pyramids. Similarly, the aesthetic proportions of the White Chapel were valued not because they seem pleasing to the human mind but because they are pleasing, and thereby celebrate the inherent meaning of forms.

25 Shrine in the tomb chapel of the governor and priest of Hathor, Ukhhotep III. The typical form of a shrine was a box or a niche for a statue, approached on steps within an enclosed rectangular space. Meir. 12th Dynasty.

To emphasize, the use of mathematics is not simply a matter of inference from architecture. The handful of mathematical texts surviving from ancient Egypt, which are essentially practical documents, include calculations for determining different geometrical properties of architectural forms, such as a pyramid or a truncated pyramid (in other words, a mastaba). Several hieroglyphic inscriptions survive to explain the layout of temples and state their architectural forms in ideal terms, using specific proportions and arithmetical sequences. The mathematical sequences in turn are related to knowledge about the temple’s divine subject, just as we now relate mathematics to knowledge about the essential nature of the universe. Accordingly the temple was laid out as a microcosm of the world, and the word ‘true’ may even be written with the hieroglyph  , which is the precisely cut plinth of a monument or the casing block of a pyramid [25].

, which is the precisely cut plinth of a monument or the casing block of a pyramid [25].

The same inscriptions sometimes show the original site of the temple being measured and laid out on the ground by ‘stretching a cord’, though not by surveyors as such because this is presented as the work of the pharaoh and his priests. Once laid out, the undeveloped site is purified in various ways, mostly using water, natural minerals and animal sacrifice, until the resultant ground is said to be made up of ‘the spit of Shu’ – that is, a formless product of the energy of Creation. The building site may be given a temporary name as ‘Horus’ place of raising’, which also happens to be a variation of the name used for the White Chapel (see p. 27). At least from the mid-2nd millennium BC onwards, the laying-out ceremonies then entailed a ritual run by the king (or perhaps a run on his behalf) driving four calves along to trample in seed, a ceremony described as ‘treading the grave of Osiris’. Out of ground prepared in this way, the temple would literally rise up to become what the texts call ta tjenen, ‘the Risen Earth’, ‘which has given birth to the gods, and from which every thing has emerged – foods, crops, offerings, and everything perfect’.

The Inundation and the ‘emergence’

‘The Risen Earth’ is a simple, iconic image used in myths and hymns to identify the very ‘place’ where the Creator stands. More literally it evokes a natural phenomenon that is definitively Egyptian, insofar as it is a feature of life along the lower reaches of the River Nile. To take an example, the so-called ‘Colossi of Memnon’ are actually statues of Amenhotep III, which once stood either side of a gateway in his mortuary temple, though time has removed almost all of the rest of the temple. Nowadays the Colossi stand several hundred metres from the river but in ancient times (before modern dams were built farther south) the Nile began to rise every year in late June, until it reached a peak in August typically 8 to 10 metres (26 to 33 feet) higher than it began and not unusually up to 14 metres (46 feet) higher. With such an overwhelming volume, the so-called Inundation swept floodwater and organic debris right through the temple and far beyond, to the desert cliffs [26]. The fundamental transformation of the Egyptian landscape by the Inundation was embodied in the three seasons of the ancient calendar, namely akhet (‘inundation’), peret (‘emergence’) and shemu (‘harvest’ or ‘dry season’). Consequently, at the beginning of the new agricultural year essentially the whole land was a single body of water, bringing the potential for life wherever it reached, while anywhere beyond remained desert. Dotted about in the floodwater were peoples’ homes, workshops and farm buildings on patches of high ground, described as ‘baskets’, as though they were bobbing about until the water finally retreated by late October. Thereafter the promise of the flood was realized in the ‘emergence’ of a rich, fertile soil, out of which ‘emerged’ the crops that made Egypt’s farmers the envy of their contemporaries [27]. ‘For, these days, these folk collect their harvest with less trouble than anyone,’ claimed Herodotus, the great historian of the Greeks.

26 Archive photo showing the Nile Inundation swamping the ‘Colossi of Memnon’ in West Thebes. Quartzite. Originally over 18 m (59 ft) high. 18th Dynasty.

27 Scene of a wine-press from the tomb chapel of the governor, Pahery. El-Kab. Painted limestone relief. 18th Dynasty.

Thus in mythical terms out of the fluid Potential came the Risen Earth, and out of the Risen Earth the immanent seeds generated life in abundance. The ancient temples not only celebrated this annual cycle but were intended to become part of it through seasonal festivals and offerings, and even by welcoming the Inundation inside. A text of king Sekhemra-Usertawy Sobkhotep from Karnak during the 13th Dynasty commemorates ‘his person’s procession to the hypostyle hall of this temple so that the Highest Inundation would be seen. His person came just when the hypostyle hall of this temple was filled with water’. This may refer to an exceptional event, of course, but Sobkhotep’s procession, like the photograph of the Colossi of Memnon, at least demonstrates the proximity of most temples to the floodplain and the reach of the Inundation. Certainly some temples include ancient drains as part of their architectural foundation and, if a temple were flooded, it would also rise again during the ‘emergence’.

Corridors of stars, courts of the Sun

If an ancient Egyptian temple is laid out as a microcosm, then the built architecture of the temple is bound to embody the myth of Creation implied in the Risen Earth. This is undoubtedly true of the grand temples of the New Kingdom and later, including those built by Amenhotep III, Sety I and Ramesses II, which we will return to in Chapter 11. However, other instances will already be apparent – namely the tumuli common to the tombs of the earliest kings at Abydos and apparently all the temples associated with them at Abydos and at Hieraconpolis. We can no longer be sure what form the tumulus took in each case, but no special leap of imagination is required to connect these artificial mounds with the iconic pyramids of Egypt. Pyramids consistently featured in the tombs of the pharaohs and their queens, beginning in the 3rd Dynasty with Djoser’s Step Pyramid at Saqqara [28] and continuing until the burial of Queen Tetishery, back at Abydos, during the reign of Ahmose (c. 1539–c. 1514 BC), first king of the 18th Dynasty.

In the context of the Risen Earth, Djoser’s Step Pyramid is a clear development of the earlier royal tombs and temples. Djoser was probably the immediate successor of Khasekhemwy, and the Step Pyramid complex as a whole bears close comparison to Khasekhemwy’s ‘mortuary temple’ at Abydos (see pp. 35–36). Of course, the scale of Djoser’s tomb is greater still and the form of the tumulus is now unequivocally a pyramid, but there is also much that is familiar. The niched enclosure wall has been retained, though now modelled in stone, to enclose more than 15 hectares (37 acres) of ground. Once again a gate-complex at the southeast corner leads into a vast court open to the Sun on the south side of the tumulus. In Djoser’s complex this court has clearly been laid out as though for the ‘tail festival’, incorporating the stelae or markers illustrated on Den’s label (see pp. 40–43), though a smaller court alongside was perhaps the actual stage for the ceremonies with the vast court as its monumental counterpart.

28 Reconstructed ‘dummy buildings’ beside the south court of Djoser’s Step Pyramid at Saqqara. Limestone. 3rd Dynasty.

At the centre of the site is the pyramid itself, underneath which the king was buried. Formally Djoser’s pyramid bears close comparison to the royal tumuli at Abydos, being built by first excavating a suite of burial chambers from the desert floor, with multiple adjoining galleries to stockpile offerings. Areas of these galleries were decorated as though the walls were covered with reed mats, though the ‘mats’ were actually modelled in faience and consequently survived in good condition into modern times. Above these chambers, the engineers constructed a mastaba presumably corresponding (in more elaborate form?) to those in the royal cemetery at Abydos, but subsequently the mastaba was wholly enclosed in a solid pyramid with four steps, later increased to six steps. Notably, this reverses the construction of several older tombs at Saqqara built for high officials, where a stepped tumulus was built first, then wholly enclosed by a mastaba (see p. 147).

The enclosure wall of the Step Pyramid has fourteen dummy gates, which has raised the suggestion that the complex is not simply an interpretation of the palace so much as a model of the largest Egyptian city, Memphis. No doubt the proximity of Memphis in the valley below Saqqara was part of the inspiration for moving the royal cemetery, and perhaps the stepped form of the outer tumulus had some local significance at Memphis. That said, inside the complex are large-scale, solid models of specific chapels for the gods of about thirty districts, as well as kiosks, other buildings and the aforementioned ‘tail festival’ courts, around which several statues of the king were discovered. So the variety and character of the ‘dummy’ buildings may indicate that the Step Pyramid complex is not a model of any specific palace or city, but rather an invocation of all the temples of Egypt. Perhaps similar buildings originally featured in the mortuary temples of the earlier kings at Abydos, but there had been modelled in mud-brick, reeds and other perishable materials. Perhaps the fourteen gates at Saqqara also relate to the number of boats beside Khasekhemwy’s mortuary temple. On the north side of Djoser’s pyramid, the complex is now terribly reduced and harder to fathom, though it had a different layout, relying on enclosed statue-chapels opening off a central court open to the Sun.

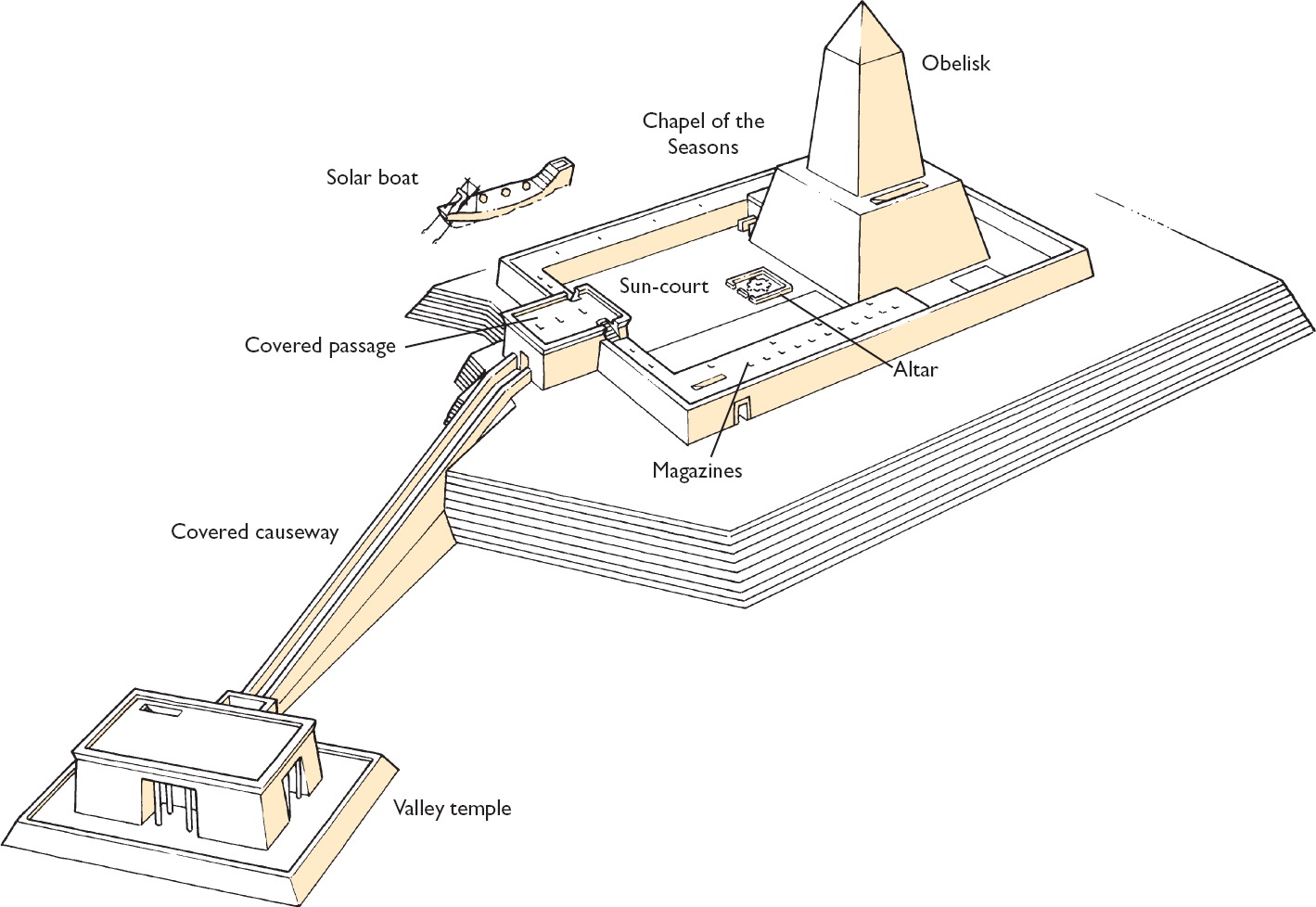

During the next dynasties, the step pyramid was replaced by other forms for the tumulus, most notably the ‘true’ pyramids, but the royal tomb complex still remains recognizably a development of what had gone before. From the 4th Dynasty, a valley temple – a feature already present in the Step Pyramid – acts as the principal gate-complex and also as a quay on the Nile not only for the king (and, presumably, eventually for his burial procession) but also for the statues of gods making their festival processions. The principal path through the valley temple makes use of hypostyle halls, which are roofed chambers with far more columns than are required for structural reasons. The columns are there to manage the influx of light while approaching statue-chapels. In other words, the chapels themselves were maintained in total darkness, until such time as a priest or officiant introduced an artificial light of some kind (see pp. 95–97). Exiting the valley temple the next transition is mediated through an enclosed, dark causeway with a star-covered ceiling, which climbs upwards, often hundreds of metres, to a mortuary temple on the summit of the cliffs overlooking the Nile floodplain.

29 Schist dyad of Menkaura and a queen, from his valley temple at Giza. 1.39 m (4 ft 7 in.) high. 4th Dynasty.

Entering the mortuary temple through a hypostyle hall, the covered path leads into a court, suddenly and dramatically open to the intensely bright Egyptian daylight. On the far side of this Sun-court stood another hypostyle hall, reducing the light before entering an area of five or more chapels, each with an enthroned statue of the king. Not surprisingly, the valley temples and mortuary temples of the pyramid complexes are the original source of many of the celebrated statues of the Old and Middle Kingdom pharaohs [29]. Interior walls were decorated with images of the fecundity of the land, as well as images of the ‘tail festival’ and the beneficence of the king [30, 31]. In many instances the columns are shaped as marsh plants, consistent with the Risen Earth as a concept, though there was no possibility of the Inundation reaching such a height. As we may expect, the king’s tomb complex also contains subsidiary burials, mostly for his queens with their own smaller pyramids, while immediately around and about were the interments of his officials, sometimes laid out in what seems like street upon street of mastabas.

30 Personifications of the fecundity of Egypt bring water, sprouting grain and offerings, along with authority, life and joy. Above is a sky full of stars and a register showing various gods. From the mortuary temple of king Sahura at Abusir, near Saqqara. Painted limestone relief. 5th Dynasty.

31 Emaciated men, women and children, from the pyramid complex of king Sahura at Saqqara. The scene, though difficult to interpret out of context, may illustrate the potential difficulty of life outside the pharaoh’s realm. Saqqara. Painted limestone relief. 5th Dynasty.

Of course, whether visitors arrived at the valley temple or stood in the Sun-court of the mortuary temple, their view would have been dominated by the pyramid itself. The model for the true pyramid form is the obelisk that stood at the heart of the temple of Ra-Horakhty, a god whose name means ‘the Sun is Horus in the Horizon’. His temple was on the east bank of the Nile at Heliopolis, and the scant remains suggest it once covered an area as large as any temple ever constructed in Egypt. By the 4th Dynasty not only the royal pyramid itself but the enclosure wall, the causeway and other external features of the tomb complex had replaced the niched palace façade with a smooth exterior finish of the finest white limestone, from the Tura quarries near modern Cairo, intended to play with the rays of the rising and setting Sun. In ancient times the rising Sun reflecting on the Great Pyramid at Giza and many other royal pyramid complexes would have been visible from the temple of Ra-Horakhty on the far bank.

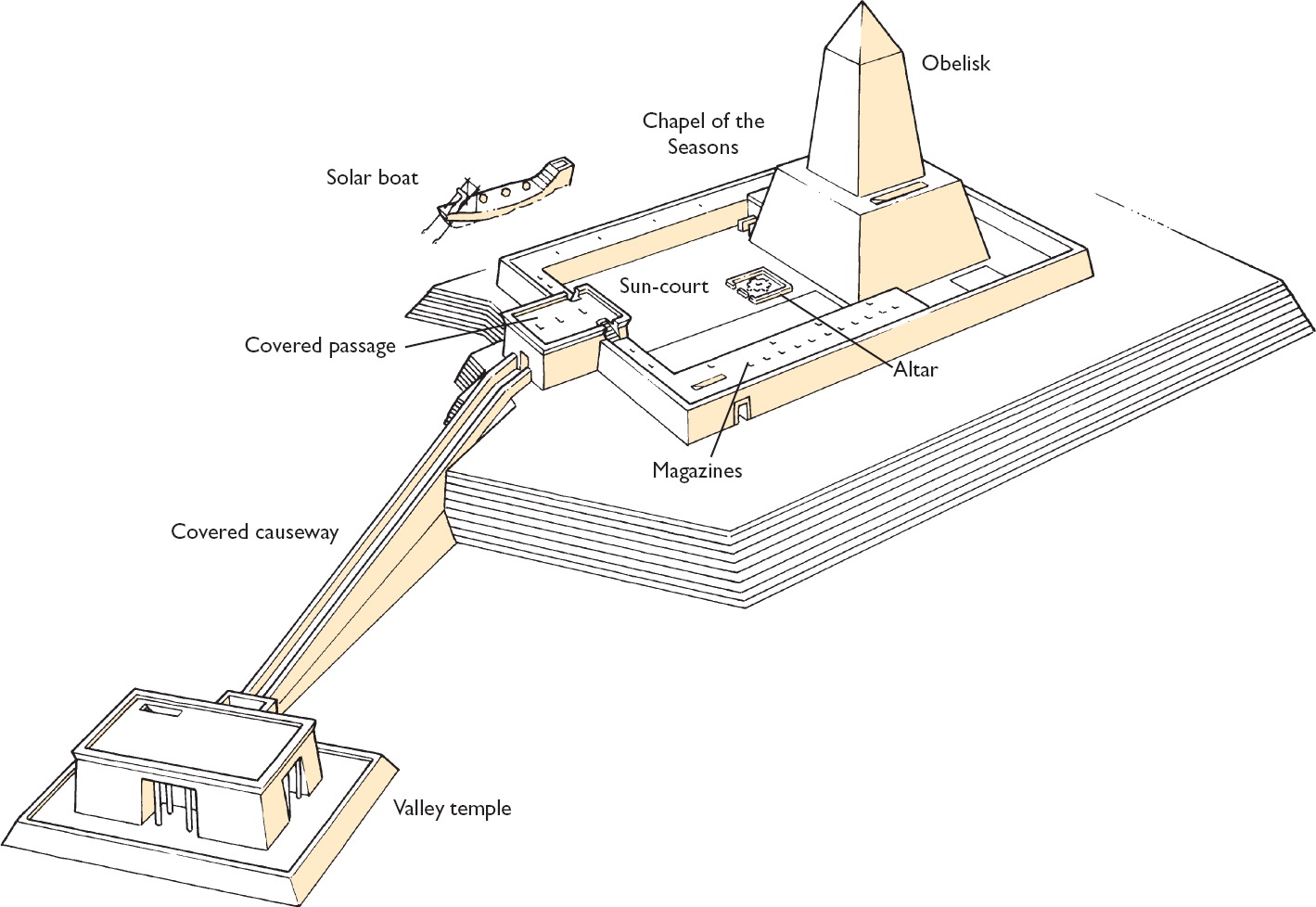

Although the temple of Ra-Horakhty at Heliopolis is now all but lost beneath Cairo, its form during the Old Kingdom may well be reproduced in the 5th Dynasty Sun-temples on the west bank of the Nile at Abu Ghurob [33]. In turn, the layout of these temples is analogous to the royal pyramid complexes beside which they stand, though the Sun-temples also feature an oversized calcite altar shaped to form the hieroglyph  ‘offering’ as the centrepiece for ceremonies conducted in front of a massive obelisk. At this altar – and presumably at Heliopolis too – verses from hymns to the Creator (addressed as Atum or as the Sun) were sung every day at daybreak and sundown, while at the same time offerings were presented in the neighbouring pyramid complexes to the enthroned statues of kings. A chapel beside the platform of the obelisk celebrated the fecundity of the land through the cycle of the seasons with brightly coloured images [32], comparable to the decoration in royal palaces at a later date (see p. 31).

‘offering’ as the centrepiece for ceremonies conducted in front of a massive obelisk. At this altar – and presumably at Heliopolis too – verses from hymns to the Creator (addressed as Atum or as the Sun) were sung every day at daybreak and sundown, while at the same time offerings were presented in the neighbouring pyramid complexes to the enthroned statues of kings. A chapel beside the platform of the obelisk celebrated the fecundity of the land through the cycle of the seasons with brightly coloured images [32], comparable to the decoration in royal palaces at a later date (see p. 31).

Traditionally, changes to the particular form of the royal tumulus have been explained in evolutionary terms, as though the ancient engineers were making gradual progress towards a desirable outcome that was too advanced for them to know yet. In this scenario, the step pyramid form is an intermediate stage between a mastaba and a true pyramid, while the ‘bent’ pyramid form (in which the angle of the sides changes partway up) and other shapes for royal tumuli are disparaged as experimental mishaps, which the builders were nevertheless obliged to complete for some reason. If this were so, Snofru, first king of the 4th Dynasty, completed at least three of the largest pyramids ever built in order to get one in the shape he wanted. Without doubt some innovations were required by the developing technology of pyramid building, especially the engineering innovations that deal with relieving the increasing weight of the ever larger (and always solid) tumulus above the subterranean chambers. Nonetheless, a more sympathetic interpretation of events is that there was change and development during the 3rd and 4th Dynasties because meaningful choices were still being made regarding the appropriate form of the tumulus to be used in royal tombs. For example, successive kings introduced the step pyramid form, the bent pyramid form [34], successfully added internal chambers to the pyramid itself, and even reverted to the mastaba form, though these innovations were all subsequently abandoned.

32 Scene from the ‘Chapel of Seasons’ showing the Nile Inundation at top, and below men trapping water-fowl while a cow and calf come down to graze. The two figures at top are bent to their activity and have exaggeratedly large heads. From the Sun-temple of Nyuserra at Abu Ghurob, near Saqqara. Painted limestone relief. 0.72 m (2 ft 4½ in.) high. 5th Dynasty.

33 Reconstruction of a Sun-temple built for the 5th Dynasty king Nyuserra at Abu Ghurob, whose layout is analogous to that of a royal tomb complex but centred on a monumental obelisk rather than a pyramid.

Probably the form of the obelisk in the temple of Ra-Horakhty explains some of the innovation during the 4th Dynasty. The central obelisk of the Sun-god was named benben and featured a pyramidal pinnacle, possibly gilded, called the benbent, both words based on the indigenous word for ‘rise’ (as in ‘sunrise’). Now, Snofru’s ‘bent’ pyramid at Dahshur has the form of the benben, whereas his ‘true’ pyramid at the same site is based on the shape of the benbent specifically. At Meidum Snofru’s oddest-shaped pyramid – which has been made to look even odder by later plundering for cut stone – may be a bold attempt to reproduce the shape of the whole obelisk including its platform [35], just as the whole obelisk was reproduced on a smaller scale in the temples at Abu Ghurob. The pinnacle of the Meidum pyramid in its present condition is stepped, though we cannot be sure whether the step pyramid was originally the intended outer shape, or the steps were meant to be encased in a different outer form. In the end, however, during the 5th Dynasty the straightforward, elegant and stable form of the true pyramid (that is, the shape of the benbent), rising as steeply into the sky as the solid mass of each pyramid easily allowed, became established as the appropriate form of tumulus for royal tombs, and henceforward was retained at least until the royal burials moved to Thebes in the 11th Dynasty (see pp. 180–81).

34 The ‘bent’ pyramid of Snofru at Dahshur. 4th Dynasty.

35 The pyramid of Snofru at Meidum. 4th Dynasty.

If only for the sake of variety, change trumps continuity in any discussion of architectural and artistic development, so the changing form of the royal tumulus during the Old Kingdom tends to dominate accounts of early royal tombs in ancient Egypt. Nonetheless, the central fact of the tumulus – embodying first the Risen Earth and eventually also the ‘risen’ Sun in the benben – is constant, as are the inclusion of the Sun-courts, the placement of subsidiary burials round the king and so on. In many instances, the burials of full-size boats are still known to feature until at least the 12th Dynasty, and obviously this is a quite specific phenomenon that recurs from the beginning of royal burial in Egypt. In the same vein, the early royal burials moved from Abydos to other cemeteries, including Saqqara and Giza, which were already in use and dotted with the mastabas of high officials of the earliest kings (see pp. 74–77). This is not to say that the changing shape of the royal tumulus did not have specific relevance to the site of a given tomb, nor that the shifting choice of location was devoid of significance. Quite the opposite. The clear connection between the sites of many ‘true’ pyramid burials and the temple of Ra-Horakhty at Heliopolis has been noted. However, even the name Ra-Horakhty incorporates the name of Horus, and acts as a link back to the earliest kings and the mythology of Osiris, Isis and Horus. Likewise, the interplay of light and darkness in the hypostyle halls and Sun-courts round the pyramids is a constant theme, which recalls the Creator’s first act upon ‘the Risen Earth’ – to speak the names of ‘energy’ and ‘matter’.

As a final note, at the end of the 5th Dynasty the earliest ancient Egyptian funerary texts begin to be inscribed in the royal tombs (hence they are prosaically named by modern scholars ‘the Pyramid Texts’). The poetry of these hymns or speeches entwines three distinct but harmonious visions of the immortal and eternal, each of which may be recognized in the built architecture of the royal tombs. First is the endless procession of stars through the night sky, particularly the circumpolar stars, which never set nor come and go with the seasons. Second is the myth of the dead father, Osiris, and the living king, Horus, in which birth and death are the scheme whereby all things have a beginning, a lifetime and an end, so the meaning of things is revealed in time (‘not all at once’, as Einstein is said to have remarked). Third is the perpetual boat-journey of the Sun-god through the firmament, intentionally forming the world out of Potential. Hence, the Pyramid Texts are able to picture Egypt coming together at the king’s funeral to address him in words such as these:

The town of Pe is sailing upstream to you, and Hieraconpolis is sailing downstream to you. For you the mourner is wailing, for you the shrine-priest is robing. Yours is a welcome to your father. Yours is a welcome to the Sun. The doors of the sky are opening for you, and the star-covered ceilings are sliding back for you.

Masterpiece

Greywacke statue of Menkaura

The valley temple of the pyramid complex of Menkaura, of the 4th Dynasty, contained at least five greywacke statues, each of which shows the king in the company of the goddess Hathor and one of Egypt’s districts or temples. As we may expect, the divine Hathor and the districts are each personified so as to appear in the ordinary company of the king. In addition, the face of Hathor here (left) also seems to be that of the queen, who is shown alongside the king in the near life-size statue from the same temple. This particular statue is about half life-size, and cut with a simple back pillar for all three figures, which keeps them grouped and also allows the sculptor to form the crowns of the figures in a way that is not prone to damage. Hathor is the figure on the king’s right, with cows’ horns and a Sun-disc on her head; the personified district on his left is Hiw, south of Abydos, and the standard on her head shows the goddess Bat (see p. 24). The plinth is used to identify the characters and give the typical words of the goddess to the king, ‘to you I have given all life, stability and authority, all health, all pleasure’ (see p. 20).

36 Greywacke statue from the valley temple of king Menkaura at Giza. 0.93 m (3 ft 1 in.) high. 4th Dynasty.

The central figure of the king is slightly striding, which reduces the static character of the composition, while adding the dynamic of ‘approaching’ consistent with the context of offerings. There is also movement implied in the tension of the king’s detailed physique, and in the relative placement of the characters. Hathor stands slightly behind the king, adding depth to a composition that would otherwise seem utterly two-dimensional. Still, there is no suggestion that they are not together, and indeed she is holding his hand. Subtly, the three figures look in slightly different directions, adding a further axis of movement to the composition, though again this has been done so discreetly as not to be intrusive nor disrupt the cohesion of the group.

The king is wearing only a heavily pleated kilt, and his physique is modelled forcefully. Without overmuch detail, the muscles, tendons and bones are realized prominently using bold lines in just a few key areas, especially in his torso and legs but also his bullish face, which has exceptional, naturalistic detail in the eyes and lips. The female figures are static by comparison, and modelled in such a manner as to emphasize their naked torsos, most obviously by exposing their navels and demarcating a ‘pubic’ triangle. At first glance, there seems little reason to suppose they are clothed at all, other than the hemlines across their shins. However, the dresses would have been painted a brilliant white originally and the collars, now barely visible, would have been polychrome, so the apparent nudity would have been less intrusive (see p. 87). That said, the dresses must be an artistic conceit because nothing so tight could have actually been worn in life.

The proximity of the prominent, powerful king and voluptuous female companions is blatant, especially if one of them really does have the queen’s face. This juxtaposition is characteristic of every statue found in Menkaura’s valley temple, though by no means all of them put the king in the centre nor necessarily make the female figures subordinate. Hathor is obviously smaller than the king but in a proportion that seems consistent with men and women in real life. The other female figure, whose oddly high breasts conform to the pectoral line of the king, is taller than the goddess and simply stands beside him as though she were somehow a counterpart rather than his more intimate companion. In any event, because the context is the king’s tomb, the sexuality can hardly be overlooked. First, there is the simple juxtaposition of procreation to death, especially in reference to the myth of Osiris, Isis and Horus. Second, and prominent in the context of offerings for the dead king, there is the life-bearing fertility of the districts of Egypt. Finally, since the laying out of a temple presumably involved the pharaoh trampling in seed at ‘the grave of Osiris’, with this statue we come full circle. Here the harvest of the land may be offered at the dead king’s tomb.

37 Schematic reconstruction of a typical Old Kingdom pyramid complex; compare the Sun-temple complexes of the same era [33].