CHAPTER 6

The Rebirth of Education as Starfish Ecosystems of Educators

Our lives have been transformed by two different logics that have brought starkly different outcomes: Moore's law and Baumol's cost disease.

We are today awash in computing power, electronic memory, and communication bandwidth. The typical American teenager plays games with more computing power than NASA used to send a man to the moon—and back (which was the impressive part). Cell phones have penetrated the planet; at their peak expansion more cell lines were added each month in India than the total number of landlines available in 1994. The bandwidth to share text, images, and video is nothing short of astounding.

In 1965, Gordon Moore noticed that the number of transistors that could fit on an integrated circuit chip had doubled every two years since 1958, and he thought the trend might continue, at least for a decade. Dubbed Moore's law, the contention that integrated circuit capacity—and other measures of computing power—would double every two years has proved uncannily accurate up to today. As a result, computing power has become essentially free: the Yale University economist William Nordhaus (2007) calculates that compared to manual computing—the only possibility in, say, 1850—our computing power is several trillionfold higher, and that since 1950 the economic cost of computing has fallen by a factor of a billion. The spectacular software and Internet applications used every day by hundreds of millions of people around the world—Google, Wikipedia, Facebook, Skype, not to mention the ubiquitous cell phone—are built on the hardware foundations of Moore's law.

In 1966, William J. Baumol and William G. Bowen, writing about the performing arts, noted exactly the opposite phenomenon. They pointed out that it takes the same time to perform a Mozart symphony today as it did in Mozart's time. Therefore, the cost of a live performance of a Mozart symphony must increase as the price of labor increases; there cannot be gains in labor productivity. This relationship, namely, that there are labor-productivity-resistant services whose cost must increase with the cost of labor, has been labeled Baumol's cost disease.

As we have seen in earlier chapters, basic education has not experienced productivity increases that would accord with Moore's law. On the contrary, in many countries the performance of learning has been even worse than that predicted for Baumol's disease as costs per student have risen even as measures of student learning have fallen.

While Moore's law and Baumol's disease have some underlying technological foundations, both are the result of the organization of human systems. Moore's law, which began as a crude heuristic based on the past, became a goal for the future for the people and the firms in the domain: they had the performance pressure of making Moore's law take effect, again and again, and they succeeded in doing so. In contrast, some sectors have allowed Baumol's cost disease to become an excuse, and organizations construct the camouflage of isomorphic mimicry to insulate value-subtracting and rent-extracting organizations against performance pressures, thus creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of stagnation and decline. The rebirth of education will require schooling systems to be freed from their Taylorist roots as instruments of uniform implementation of a top-down program and transformed into systems that free, foster, and scale innovations and dynamism.

Spiders are neither better nor worse than starfish; they are each the result of natural evolution and have claimed niches in an ecosystem. The key question is what mode of system organization is best adapted to a particular challenge. The schooling challenges of past decades, particularly the logistics of physical expansion, are adequately handled by spider systems. However, the challenges of the future, of using schools to create viable opportunities for the children of the twenty-first century by promoting learning, can best be met by starfish systems. Perhaps paradoxically, this is especially true in developing-country contexts, where people see the need for “order” but the spider systems are at their weakest (Pritchett 2013).

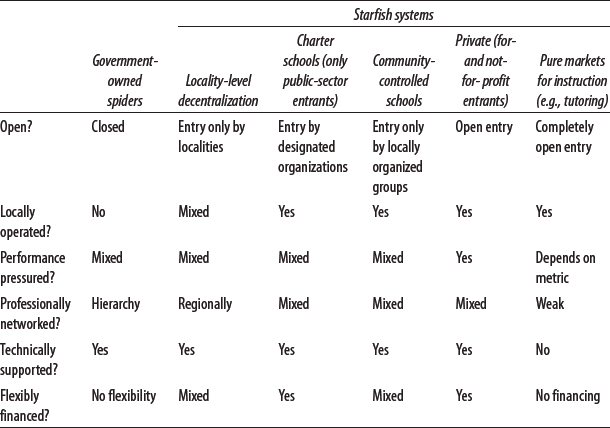

But just being a starfish ecosystem is not enough. There are six traits of an effective starfish ecosystem needed for quality education:

— Open: How is the entry and exit of providers of schooling structured?

— Locally operated: Do those who manage schools and teach in schools (and the local coalitions of parents and citizens they are accountable to) have autonomy over how their school is operated?

— Performance pressured: Are there clear, measured, achievable outcome metrics against which the performance of schools can be assessed?

— Professionally networked: Do teachers feel a common professional ethos and linkages among themselves as professional educators?

— Technically supported: Are the schools, principals, and teachers given access to the technical support they need to expand their own capacities?

— Flexibly financed: Can resources flow naturally (without top-down decisionmaking) into those schools and activities within schools that have proved to be effective?

These six elements do not dictate the exact design of a system. It would, of course, be contradictory to decry spider systems and then insist on a single model or instantiation of a starfish system. But the pieces of a starfish ecosystem do have to be coherent. There are hundreds of types of automobiles in the world, from Mini Coopers to Formula One racers to luxury sedans. Each of those vehicles works. Each has interrelated functional systems of engines to generate power, transmissions to take that power to the wheels, brakes to stop the car, and steering mechanisms to guide the car. But ramping up these subsystems one at a time doesn't necessarily produce a better car—strapping a massive engine into a Mini Cooper with the same transmission and brakes makes it a death trap, not a hot rod.

I am not going to tell you how to design the best car, or the best engine, or the best brakes. I realize that many of those reading this book will be disappointed, having hoped for a blueprint, a ready-made model for success. I probably could provide such a model, but I won't, for four reasons. First, as the Zen teaching goes, “If you should meet Buddha on the road, kill him” (a statement that, in keeping with the Zen koan tradition, I cannot explain). Second, the implementation of starfish principles must be contextual. I have worked on education issues in India, Argentina, Paraguay, Indonesia, and Egypt (among other countries), and, while I might be able to provide for each a starfish system approach conforming to the six desirable traits listed above, in each case the exact formula would be very different, depending on existing political, social, and educational contexts. Third, the book is already long. In a book like this I can only provide a vision of what a system of education could be, not a buildable blueprint. But blueprints of successful systems can and are being built on the foundations I describe. Fourth, if you don't design it, it isn't yours, as you cannot juggle without the struggle (Pritchett 2013).

Success at Scale Requires Systems for Scaling Success

One charge that could rightly be leveled at this book so far is that the general tenor is pessimistic: chapter 1 says learning levels are low; chapter 2 tells us more years of schooling won't solve the learning problem; chapter 3 argues just more inputs alone will provide a little help, not a lot; chapter 4 suggests more of the same can actually block better learning; chapter 5 argues that the systems we have were built for ideological socialization in the nineteenth (and twentieth) centuries, and not for developing student capabilities to meet twenty-first-century needs. And now I want to talk about creating a positive dynamic of progress?

But success is out there. There are many actors out there in many guises—in the private sector, among NGOs, and inside government systems—doing fantastic things even in difficult country contexts such as Pakistan and Nigeria and Nepal. The problem is that failure is out there too, and we haven't figured out how to consistently build education ecosystems whose natural operation would promote the good and weed out the bad. Lots of people have figured out how to build good, even great, schools—which is terrific—but what I want to imagine is an ecosystem of schooling from which better and better schools are the natural outcome.

Success Is Already Available, in Lots of Contexts

The cause for optimism is that, even in countries with poor average results, and even in the most difficult situations, such as isolated or rural environments, there are schools that succeed in promoting high levels of learning. This is true among community and NGO efforts, with budget-level private schools, and in the government sector.

Community and NGO Schools

Concern over the quality of government schools has produced activists and NGOs that either run their own schools or intervene in various ways to increase learning in government schools. Worldwide, a number of individuals and movements have started and operate schools. The Fe y Alegria movement, which was started by the Jesuits in Venezuela in 1955 to promote comprehensive education and social change, has grown to have more than a million students reached with one type of activity or another. Recently, Bunker Roy and his “barefoot” approach in Rajasthan India have received wide attention. Both these efforts are the continuation of a long heritage of similar approaches.

Many NGOs have been engaged with academics in doing rigorous evaluations of the learning impact of their interventions and so have hard evidence of the massive gains available. For instance, the Indian NGO Pratham did remedial education in classrooms in two cities in India by pulling out the students who were behind to work with tutors for half of the school day. Studies showed that the learning of students who began in the bottom third improved by .43 standard deviations (Banerjee, Cole, et al. 2010). In a different setting, village volunteer tutors were trained for a mere four days, after which they were able to help children develop the fundamental skills required for them to succeed in school and raised the proportion of children who could read by 23 percent (Banerjee, Banerji, et al. 2010). A month-long summer camp that targeted low-performing children in Bihar, India, raised over half of these children one level in reading (out of five levels) at the end of a month—equivalent to the gain of a year of schooling (Banerjee and Walton 2011). These tactics have since been scaled up by the government to an entire district, with promising results (as of early 2013).

Communities themselves, even without the intervention of NGOs, can often improve schools when given the chance. An evaluation of the effect of turning schools over to community-based management in Nepal found significant decreases in school attrition rates (especially among disadvantaged groups), improvements in school processes (such as whether principals warned teachers about nonperformance, and improved outcomes on science learning assessments) (Chaudhury and Parajuli 2010).

But my point is not to single out specific NGOs or their ideology, or specific interventions; nor do I propose community-based management as the best approach and one that should be replicated. The point is, there is a continuous stream of available innovations out there, literally thousands of local examples of success, spanning every region and country, but many scale too slowly to have an impact on national learning outcomes. Even as dozens of fantastic actors and innovations on the education scene in India are improving outcomes locally, the national learning outcome continues to stagnate, or worse, as the latest ASER results suggest flattening learning profiles (ASER 2013).

Private Sector: Budget-Level Private Schools

One of the ways in which parents have coped with failing and unresponsive public school systems has been to move into private schools. Whereas formerly only the elite may have gone to private schools, there has been a massive proliferation of private schools, especially in Asia and Africa. These budget-level private schools are producing better learning outcomes, often substantially better, than publicly controlled schools—even for the same students—and often at much lower cost.

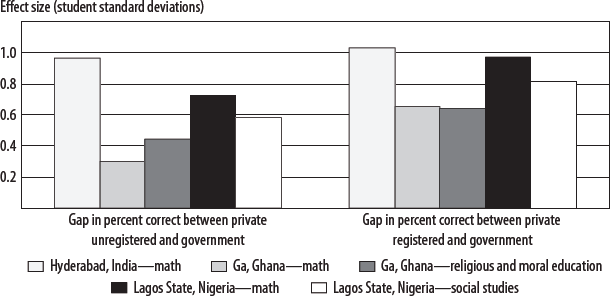

Tooley and Dixon (2005) compared private schools and government schools in four urban areas, three in Africa and one in India, on learning outcomes in math and language. In some of the locales the learning outcomes in mathematics were higher in the private schools by almost an entire student standard deviation. These differences are shown in figure 6-1, where I also include other tested subjects, such as religious and moral education in Ga, Ghana, and social studies in Lagos, Nigeria, to show that these gains owe not simply to private schools concentrating exclusively on math, as the learning gaps are just as large. One of the most important features of this study is that it included not just the prestigious and exclusive private schools but also schools that operate completely outside the current educational systems as unrecognized or unregistered schools. Even in these schools, which do not attract wealthy or elite students, the students are outperforming those in government schools.

Of course, these findings don't prove that private schooling is the cause of the superior performance. The hardest thing about deciding whether private schools are performing better is not knowing whether students in private schools are performing better—they almost always are—but whether the improved student performance is because of a selection effect, so that children who would otherwise have performed better anyway are in private schools, or because private schools provide more learning for the same students.

Figure 6-1. Even unregistered, low-cost private schools have students outperforming those in government schools.

Source: Tooley and Dixon (2005).

As discussed in chapter 4, the LEAPS study in Pakistan shows that children in private schools are between 0.7 and 1.2 student standard deviations (depending on which subject) ahead of students in private schools, even for the same underlying quality of student (statistically speaking).

This isn't to say that across the board, private schooling is better than that available in government-run schools; in general, the evidence that private schools outperform government schools in well-functioning systems of education is weak. In the United States, where there has been the opportunity to do the most rigorous experimental studies, most researchers agree that the private sector edge in learning is nothing like a full effect size, almost certainly not even a tenth of an effect size, and some legitimately dispute whether the private sector causal impact is even positive. Even in India the estimates of the gains from private schooling range from zero in some states to almost a full student standard deviation in others (Desai et al. 2008). In Uttar Pradesh, given what we have seen in previous chapters about its weaknesses, the typical student has learning higher by 0.69 of an effect size by being in a private school.

Government Schools

Thus, the learning increments from private schooling noted above do not speak against the capability of governments to produce educational success; indeed, governments can and do produce massive gains when the conditions are right. For instance, one set of efforts has focused on getting children reading fluently in early grades. An increasing body of evidence from interventions that follow the “five T's” (time on task, teaching teachers, texts, tongue of instruction, and testing) supports the concept that early intervention can produce massive results. In the Early Grade Reading Assessment Plus (EGRA+) in Liberia, a rigorous evaluation showed effect sizes in oral reading and reading comprehension of 0.8 (Korda and Piper 2011). Similar experiences include Breakthrough to Literacy in Zambia (USAID 2011), the Malandi District Experiment in Kenya (Crouch and Korda 2009), Systematic Method for Reading Success (SRMS) (South Africa) (Piper 2009), and Read-Learn-Lead (RLL) in Mali (Gove and Cvelich 2011).1

Broader than just the success of specific interventions inside government schools is the observation that even in low-performing government systems one finds excellent schools—but also, even nearby and even operating under apparently exactly the same conditions, terrible schools. The LEAPS study in Pakistan found that in English performance, the best government school scored 845, only slightly behind the best private school, which tested at 850. However, the worst government school averaged only 84, or tenfold lower. The problem is not that government schools cannot succeed, for in nearly all developing countries some of the very best schools are government schools. The problem is, as the LEAPS study authors emphasize, “when government schools fail, they fail completely” (Andrabi et al. 2007, 31).

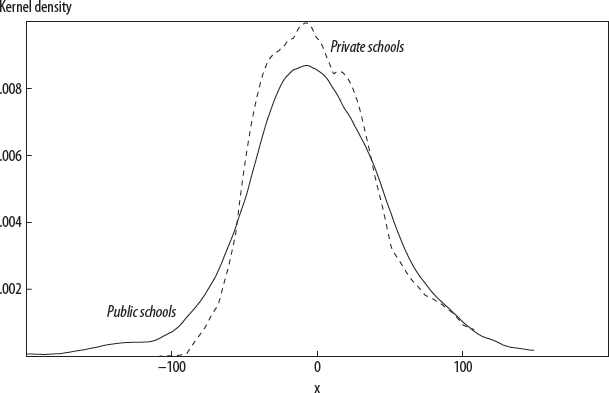

The upside of the high-performing government schools is that they prove it is possible. The question is how to bring the lower-performing government schools up to the standard of the high-performing government schools. And the answer isn't inputs. In Pritchett and Viarengo (2009) we used the PISA data to calculate the difference in the average scores of students in different schools, differences evident even when statistically the schools had the same students and the same inputs. We found that even when there is the “illusion of equality,” namely, that all public schools have the same processes and procedures and inputs, there are massive differences in what students know. For instance, in Mexico the student standard deviation on the PISA assessment was 79 points. The standard deviation across government schools, even adjusting for the background characteristics of students and for measured inputs, was 30 points. So if the weak schools (one school standard deviation down) could reach the same level of performance of the strong schools (one standard deviation up), the average student scores could increase by 60 points—which is a substantial part of the gap between the United States and Mexico. As figure 6-2 shows, the difference between government and private school quality in Mexico is not at the top, it is at the bottom, with very weak schools in adjusted (for students and inputs) learning.

Figure 6-2. Both government and private sectors have top-performing schools in Mexico on the PISA assessment, but essentially all of the weakest-performing schools—those more than 100 points below the average—are government schools.

Source: Pritchett and Viarengo (2009).

Unleashing the Power of Loosely Coupled Systems for Education

Why don't all these great ideas about how to do education scale better?

The problem in education doesn't seem to be a need for better mousetraps but that the available mousetraps are not being sprung.

There is a joke that economists tell that is worth telling because it is telling. An economist is walking down the sidewalk toward his friend. He walks right by a hundred-dollar bill lying on the ground. His friend is stunned. “I thought economists valued money.” “Oh, it cannot have been a hundred-dollar bill. Had it been a real hundred-dollar bill, the free market would have picked it up already.”

Advocates in education, on the other hand, seem to have no end of (metaphorical) hundred-dollar bills—great ideas and interventions that, if only they were to be adopted, would lead to large improvements in quality of learning at low cost. As obtuse as it may seem, one does have to stop and ask, “If your idea is so great, why isn't it already the existing practice?”

In 1997 two guys thought they had a better idea for searching the Internet. In 2011 some 4.7 billion searches were done using their search engine every day. Larry Page and Sergey Brin no longer spend time convincing people Google has better search algorithms. People tried it, liked it, adopted it, and it scaled (and wow, did it scale!).

In 2004 a college sophomore thought he had a cool idea for how people could interact over the Internet. By 2012 there were a billion people using Facebook. People tried it, liked it, adopted it, and it scaled (and wow, did it scale!).

But spider systems can block great ideas from scaling. The most dramatic shift from spider systems to starfish systems in my lifetime has been in telephone service. With the old wire-based technology, telephone services were a “public monopoly” and hence were either taken over completely by government firms or strongly regulated. In places with reasonable governments, this did not work too badly, and access to telephones expanded and things worked OK. In India in 1998, more than a hundred years after telephone service had become widespread, there were only 14.9 million landlines in India. The regulators had a stranglehold on expansion of service, and getting a telephone was a Herculean feat (of patience, political connections, and/or bribery).

With the advent of cellular technology, telephone service switched from being something a spider could dominate to a starfish system where people could just do it. In 2010 there were more people getting a cell phone, and hence access to a vital service—15 million in a month—than got a landline in the first fifty years of Indian independence. This break from a top-down spider system has been replicated around the world. African countries with governments incapable of managing anything have had massive expansions of cell phone coverage. You can get a working cell phone in South Sudan (I have) or Somalia (I hear).

How does system design promote appropriate scaling up? A system design answers the questions of who does what and why.

Suppose a girl shows up at the door of a school today, ready, anxious, and able to learn. What must happen for this girl to have a successful schooling experience that will produce an education that prepares her to meet the challenges she will face in her adulthood (which will last almost until the twenty-second century)?

There must be a place to learn, and that place can be more or less conducive to learning. There must be learning materials of various kinds, from desks to chalk to textbooks to laboratory equipment. There must be a curriculum: people have to know what the learning objectives for this girl are, what is it that she should learn. There must be teachers who have command over the material to be taught and possess some pedagogical knowledge about how to teach someone, and these teachers must be motivated to teach. There has to be some way of assessing the girl's progress and using that feedback to dynamically shape her learning experience.

Even at this incredibly schematic level of description this is already a lot of things to do, involving in one way or another many different people with quite different skill sets. Some people have to know how to build buildings, some people have to know how to make books, some people have to know how to measure learning, some people have to know how to teach, some people have to know how to teach other people to teach.

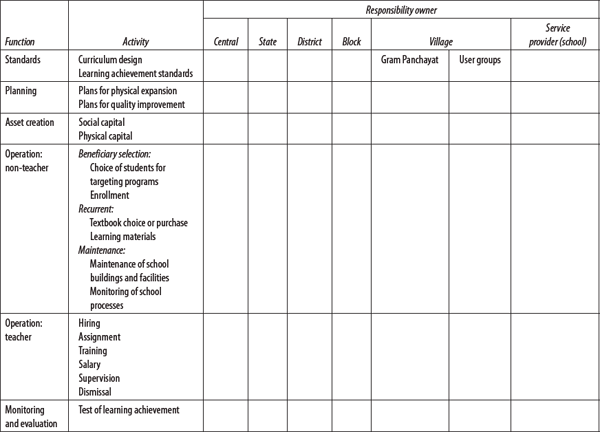

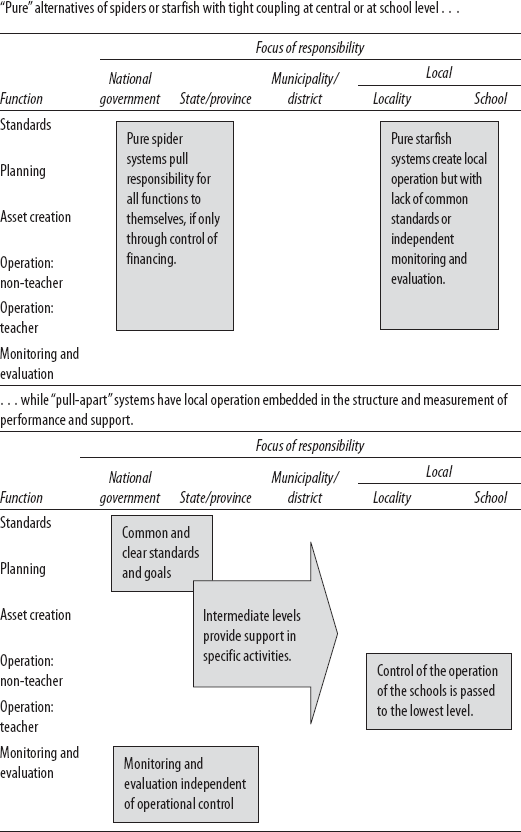

How things are going to get done involves some specification of who is going to do what and why. Table 6-1 illustrates for India the various functions and activities that go into a school system. Whether the system entails allocation across levels of government in a scheme of fiscal federalism (as in the table) or whether allocation occurs between the public and private sectors, there is some implicit or explicit allocation of responsibilities. Who is going to set standards? Who is going to build buildings? Who is going to order the chalk? Who is going to assign teachers to schools and classrooms? Who is going to assess the performance of schools?

How, who, what, and why can be answered in very different ways. Table 6-2 illustrates (again) the fundamental distinction—that can be made in many ways—between systems. One dichotomy that does not appear on the list of spider system versus starfish system distinctions in table 6-2 is “private versus public” sectors or “market versus government.” The debates over public versus private schooling are so loud and so vociferous, so full of sound and fury, it is easy to miss that they signify (almost) nothing. The business historian Alfred Chandler has shown that the rise of the modern spider bureaucratic organization in America was driven by the private sector. As he shows in The Visible Hand (1977) and Scale and Scope (1990), many of the features of modern spider organizations originated as responses to the potential (but not yet realized) economies of scale and the need for tighter organization in what were then privately owned industries, such as the railroads, steel, and oil. Well into the twentieth century, governments in America were much more like starfish—localized, less formalized, more “bottom up”—while private businesses were leading the charge in massive-scale organizations that relied on top-down control of a bureaucracy.

Table 6-1. A system is defined in part by the allocation of responsibilities across actors.

Source: Adapted from Pritchett and Pande (2006).

Table 6-2. A fundamental divide exists in system approaches.

| A | B | |

| Teleological agents | Emergent orders | Representative authors and their discipline or domain |

| Spiders | Starfish | Ori Brafman and Rod Beckstrom, organization |

| Tightly coupled | Loosely coupled | Larry Constantine, computer science (and Karl Weick, organizations) |

| High modernism | Metis | James Scott, politics |

| Planners | Searchers | William Easterly, economic development |

| Hierarchy | Polyarchy | Elinor Ostrom, politics |

| Managerialism | Owner operation | Alfred Chandler, economic history |

| Legal/rational | Charismatic/value | Max Weber, sociology |

The dominant way of organizing basic education has been to fill in the functions chart of table 6-1 entirely with the direct employees of a single ministry. In this case, the system of public support for education is exclusively a spider system, and there is little or no support of any kind flowing from the spider organization to other schools in the system. These spider systems of schooling can be national or federalized (as in India), but nevertheless remain very large. Typical school systems in large countries employ tens of thousands of teachers, with centralized responsibility for hiring and allocating these teachers. The legacy systems of basic schooling in most developing countries around the world look very similar because they are almost exclusively large government-owned spiders, both as organizations and as systems.

The choice between the spider and the starfish mode of organization is not a decision that should be made about “education” or “primary education”—rather, it depends on what is being done. Some activities are perfectly suited to a spider mode of organization, so that whether those activities are conducted by the state or by private actors, similar organizations emerge. For instance, activities that require a great deal of coordination among actors for success will be organized by spiders. The high cost of laying railroad tracks, combined with the very high cost of making sure two trains on the same track at the same time headed in opposite directions are operating safely, means coordination is essential. This has led railroad organizations to have massive scale, in both market and socialist systems. In contrast, moving things by truck sacrifices the economies of scale achievable with railroads for the gains of not needing central coordination: millions of trucks can be on the highway without any one agent being the central dispatcher.

But the spider versus starfish distinction in systems is even more complex, as often the entire chain of production requires multiple activities, some of which have larger economies of scale, scope, or coordination while others are best done locally. This can lead to different organizations making different choices. Some organizations might increase to the efficient scale of the activity in the production chain that requires the largest size, at the risk of losing effectiveness in the activities best done at a smaller scale, but decreasing the costs of coordination across organizational boundaries. But when a system is open, other organizations may remain small and deal at arm's length with other, larger spider organizations doing the activities with economies of scale.

This is the case with schooling. The scale at which standards should be set doesn't correspond at all to the scale at which teachers should be hired. These activities can be decoupled and hence carried out by completely different actors.

Learning about Schooling from Instruction

We all know how to do many things we did not learn by formal schooling. Most people have mastered at least some skills or capabilities that take years to acquire proficiency in: playing a musical instrument, participating in a sport, speaking a foreign language, knowing a religious text well. Most of these skills are acquired with instruction outside formal school settings. Moreover, key parts of education and socialization happen in voluntary associations, religion being the most obvious example. In voluntary associations, specialized knowledge and requisite beliefs are passed from one generation to another, sometimes by way of formal schooling, but often in instructional settings not affiliated with schools.

While basic schooling has some unique features, it also has much in common with other forms of instruction. Schooling is just one format in an extended, coordinated sequence of instructional episodes. Before turning to an analysis of basic education according to starfish principles, it is worth starting with the variety of nonschooling instructional experiences.

Piano lessons have a completely open structure. Suppose you want to learn to play the piano. There is a huge array of options. You can take private lessons from an independent private teacher who provides at-home lessons. You can arrange to take lessons at a local music school. You can take group lessons. You can buy a book and teach yourself. You can take an online course on the Internet. You could just buy a piano and tinkle around. Piano learning definitely has the completely open structure of a starfish (table 6-3).

The pressure on the system is for each of the possible providers of piano instruction to attract students. But how do you know if you are receiving good instruction? You can find out about piano teachers by word of mouth among your social network, or by trial and error, or through online discussions and reviews. I hated taking piano lessons, but my parents insisted I should learn at least enough piano to be able to play the hymns in church. I hated lessons with each so I switched instructors, four times. As it turns out, I just hated piano lessons.

Piano teaching is loosely networked. There is little or no public sector support for piano lessons of any type. There are few spider organizations in the actual giving of piano lessons, but there are several interesting features. First, the production of books from which to learn piano is, as a result of market forces, much more concentrated than the giving of lessons. Second, there are particular schools of piano pedagogy, such as Suzuki, that have features of a spider system.

The result is that piano lessons are widely available, but they are heterogeneous in quality (large numbers of children begin and drop out without learning much), and the different modes of instruction are strongly stratified on class and status.

Piano lessons are just one example of a completely open-structured, weakly performance-pressured, weakly networked, publicly unsupported, starfish system of instruction. A similar analysis would apply to learning to play other musical instruments and engaging in other cultural activities, such as dance or singing. Huge numbers of children participate in sports, with a mix of learning on their own, participation in instruction through organized leagues, and private instruction. This mixed mode also applies to instruction for adults, an example being learning a foreign language, which may involve a mix of tutors, taking classes offered by a range of providers, self-instruction with tapes, or Internet-based learning.

Table 6-3. Different types of instruction are available in the United States as they range across the spider-starfish continuum.

Interestingly, the public sector is often indirectly involved in markets for instruction, through licensing requirements, but does not actually produce any instruction. For example, (some) people in the United States wanting to get a driver's license not only have to pass a state test but also must demonstrate before taking the test that they have completed a mandated course of instruction. The actual instruction, however, is done through a starfish system of large numbers of small, independent driving schools.

Vocational licensing often has the same structure, with public sector requirements for both passing an examination and completing a given number of hours of instruction or training. Again, the state imposes the requirement and controls who receives accreditation to provide training, but it does not produce the training. This leaves a large body of small, independent training providers who are pressured to attract students.

The exception to the very decentralized, starfish nature of instruction in the United States might be test preparation. Test prep firms like Kaplan may capture a significant fraction of the market for paid test preparation. But in some ways, this is the exception that proves the rule. By creating a very narrow set of performance expectations, the tests (such as the SAT) themselves narrow the variability in demand from test takers: people who attend test prep classes want better test scores, full stop.

In systems of instruction, predominantly spider systems or even systems dominated by a few large spider organizations are extremely rare. Organizing the process of teaching and learning as a spider—a large hierarchical organization with multiple units—is an anomaly in the world of instructional services.

Adopting a starfish system approach doesn't mean making basic education look more like piano lessons, it means making basic education more like an open, locally controlled, performance-pressured, professionally networked, inclusively supported starfish system. These approaches can be a means to producing a dynamic system of education that can provide universally the quality of educational outcomes youth need for the twenty-first century. But they do not create a single blueprint. As the next section shows, starfish systems come in many designs.

Three Examples of Starfish Systems for Success

Three different types of successful starfish systems suggest different ways in which success can be achieved. The higher education system of the United States plus the UK (and the “Anglo” world) has achieved top status worldwide in providing quality learning. The International Baccalaureate program, run by an organization of the same name in Switzerland, successfully prepares a mix of international students for advanced studies through distance learning and evaluation in both private and government-operated schools. And the country of Brazil has improved its standings in basic education metrics through devolving control to local agents and instituting a practice of federal monies following students. These three examples underscore the many forms consistent with a starfish mode of organization and the different paths to success that can be operationalized.

Higher Education

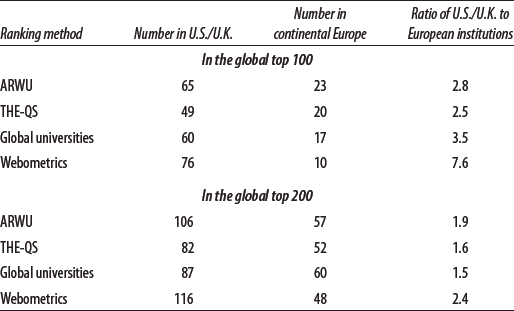

The United States plus the UK and the EU-27 (the EU minus the UK) are of similar size in population (with the EU's population slightly larger), have a similar magnitude of total economic output (with the EU's slightly smaller), have similar types of governments and capabilities, and have similar levels of completed schooling. But these two demographic areas are poles apart when it comes to the quality of higher education. The Annual Ranking of World Universities (ARWU), published by the Center for World-Class Universities and the Institute of Higher Education of Shanghai Jiao Tang University, China, ranks the world's top universities mainly on their research output and quality, as well as on how many alumni win prestigious academic awards, a ranking that leans toward schools that emphasize the natural sciences. As table 6-4 shows, the United States and the UK together have sixty-five of the world's top one hundred universities. Continental Europe manages only twenty-three of the top one hundred. The United States and the UK together have 2.8 times as many universities in the top one hundred as Europe does. Even if one moves to the top two hundred universities, the United States and the UK together still have twice as many as the EU. (Since any league table of universities inevitably inspires controversy, I used three other rankings, one from the UK, one from Russia, and one just using Web presence, to be sure this basic conclusion was robust. It is.)

While many focus on the top of the rankings, the top ten or twenty, what is really striking about U.S. and UK higher education is the depth of the bench. The “middle tier” universities in the United States would be superstars in any other country. And vice versa, the next-to-the-top universities in most countries in continental Europe would be hard-pressed to be middle-of-the-pack American universities. An example is France, a country with more than 60 million people, a glorious history, and a long tradition of academic excellence but lacking the equivalent of a Harvard or an Oxbridge, as its best universities rank with Carnegie Mellon (United States) or Bristol (UK). Even more striking is the paucity of quality universities: the third-best university in France by the ARWU rankings would be the forty-fourth best in the United States, tied with the University of Rochester. In the THE-QS ratings, the fourth-best university in France would be the forty-third best in the United States, just ahead of the University of Virginia or Ohio State University. And the French are among the better of Western Europe. Neither Italy nor Spain has a single university in the ARWU top one hundred, which puts their best on a lower ranking than the U.S. universities rounding out the top one hundred, such as Indiana University, Bloomington, and Arizona State University. In the THE-QS top two hundred the top Italian university has a global rank of 174th, and the top Spanish university is rated 171st. Again, it doesn't surprise anyone that many of the world's very best universities are in the United States, but the depth of the bench—Texas A&M, which is ranked the third best university in Texas, is ranked higher than the best university in Spain or Italy—is probably a shock to most.

Table 6-4. The quality of universities in the United States and the United Kingdom dominates that of continental European institutions, with the U.S. and the U.K. having more than half of the top 100 universities in the world.

Sources: Author's calculations, based on data from the ARWU 2009 survey, the THE-QS 2009 ranking, and the Webometrics 2009 ratings.

It is easy to rule out some possible explanations of this amazing depth in quality of the United States and the UK (given their conjoint population size). First, this is not the result of “first mover” advantages, as Harvard was barely a glorified high school when Heidelberg was hundreds of years old—not to mention parvenus that emerged from agricultural colleges like Texas A&M and Ohio State University. Second, it is not the result of “agglomeration economies,” which theoretically would allow bigger populations to support more quality universities, as the UK has roughly the same population as France or Italy.

What we know for sure is that the success of Anglo universities is not the result of spider-like top-down control. There is no “spider” inside the U.S. success: there is neither strong centralized decisionmaking with strong direction over the system nor any single organization dominating the overall system.

My argument is that the Anglo world—the United States and the UK—has produced superior results in higher education because it combines the six traits into a successful starfish system: open, locally operated, performance pressured, professionally networked, technically supported, and flexibly financed. Empirical research has shown that university research output in the United States and Europe is higher when institutions are more autonomous and there is more competition for research funds (Aghion et al. 2009).

International Baccalaureate

The International Baccalaureate (IB) is an educational organization based in Switzerland and begun in 1968 with the goal of supporting the growth of, and providing a common structure for, students preparing for higher education in international schools around the world.2 The IB has experienced significant growth since that time and is now associated with more than three thousand schools in nearly 140 countries that currently offer its programs to more than 850,000 students. The initial focus of the IB was on a two-year Diploma Program for students ages sixteen to nineteen. Since 1994 the IB has introduced the Middle Years Program and Primary Years Program, which provides structure, assessment tools, networking, and support for their programs’ students as young as age three. With its early work done predominantly in private international schools, the IB has now expanded its reach to a broader range of institutions. Over half the schools now authorized to offer one or more of the three IB programs are government-operated schools.

The schools associated with and approved by the IB organization to offer the IB show diversity in the size, structure, philosophy, and many other important educational elements. The IB does have requirements for admission of schools into participation in the program but they are based on the implementation of a certain set of educational objectives and standards for learning and assessment and little else. A school hoping to implement one or all of the three IB programs goes through an evaluation process that includes facilities and faculty, but the IB does not make significant requirements beyond this. Schools are free to define their missions and communities in many other ways, allowing the IB program to fit well into large schools, small schools, public schools, private schools, parochial schools, charter schools, and single-sex schools. Some schools elect to provide the IB program for students of all ages, while others implement only one or two of the three programs. A broad educational mission allows the IB flexibility to work within a very expansive group of educational environments and philosophies that are completely autonomous in operation.3

What the IB program does is create clear, concrete, measurable standards in each academic domain (including art and music) and provide objective external assessment of the extent to which students have met those objectives. Students’ work is submitted to the IB program, which provides independent evaluators to assess student work against the curricular objectives that were set. These are not standardized exams but rather involve portfolios of work that are assessed, and students must meet thresholds of quality to receive the IB degree.

While providing significant guidance and support for objective evaluation, the IB does not tell teachers and schools exactly how every element of assessment should take place. Particularly in the Primary Years Program and the Middle Years Program there are very few standardized tests created, graded, or even evaluated significantly outside the individual school's community. However, the IB provides significant support regarding the curricular objectives, proper assessment tools, and best methods for determining various grade levels and subjects. Additionally, the IB program makes available training and support to schools and teachers, and instruction in how to meet those standards.4

Recent Progress in Brazil

In 2000, Brazil participated for the first time in the PISA exercise and recorded the lowest scores among all countries on mathematics.5 By 2009, though it still lagged, Brazil had gained 52 points in mathematics and had the third largest gain of any country over the 2000–2009 period. Brazil has set a goal of being at OECD levels of learning quality by 2021. While it is obviously impossible to parse out the many changes that led to this progress, we can point to four things have happened.

First, Brazil set about to measure learning and progress in learning. The country initiated a sample-based biannual assessment in mathematics and Portuguese in grades four, eight, and eleven in 1995 so that learning progress could be tracked. In 2005 it moved to a census-based assessment in grades four and eight. This expansion to census (versus sample) testing means that nearly every single education establishment knows how its students are performing in learning. Moreover, realizing that schools could game learning tests by changing enrollment (say, by holding low-performing children back in grade three so they do not take the grade four examination), the Brazilian policymakers developed an index of progress, the IDEB (Índice de Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica), that combines information on school progression. Now every school, every municipality, and every state knows its IDEB score and how it is changing over time. This provides a performance metric against which many different initiatives and efforts can be judged.

Second, there was a massive reform of the financing of education between the federal government and states and municipalities that accomplished three things. (1) It established minimum levels of spending. (2) It made “money follow the student” so that municipalities, rather than seeing increasing enrollment as a cost burden, saw they could expand education and get more resources for doing so. (3) The funding was flexible within categories (for example, of teacher and non-teacher inputs). This caused a massive rise in the proportion of students enrolled in municipal versus state-run schools.

Third, traditionally, the federal government had played little or no role in education, with states taking the lead. The federal government ramped up its support in core areas while not taking on the actual running of any schools. The federal government created the legal framework, established the curriculum, focused on measurement, provided technical support in the form of textbooks and teacher training, and targeted support to low-performing municipalities.

Fourth, the Brazilian government addressed problems of income inequality and poverty by creating transfers that supported poor households with school-aged children. By 2009 more than 17 million students were supported by cash transfers to their households based on their attending school.

Principles of Successful Starfish Systems

The essence of a starfish system of education is to move from a top-down, integrated system that controls all aspects of schooling to a system that is only loosely coupled so that small units—schools and small groups of schools—have greater autonomy. But, as experience with decentralization and with market systems has shown, merely having autonomy does not ensure positive results. The ecosystem determines outcomes. Each of the six traits is reviewed to see how it fits into the overall system design.

Open

How open is the system to novelty? How many new genetic variants are produced in each generation? How likely is it that any incumbent school will face a challenger?

In a pure spider system, new schools are created when and where the top agency decides schools are to be created. Each new school is essentially a clone of existing schools and is operated by the spider as an extension of the existing system. Entry of schools into the system, particularly schools that are part of the public ecosystem and receive public financing, adds no novelty to the system.

The essential characteristic of openness of a basic schooling ecosystem means that new schools can be new. New schools can bring in new ideas, new people, new pedagogical techniques, new modes of socialization. In other words, they introduce novelty into the system. However, a balance must be sought so that the system is open to novelty while those dimensions that support the purposes of publicly supported education are protected from excessive change.

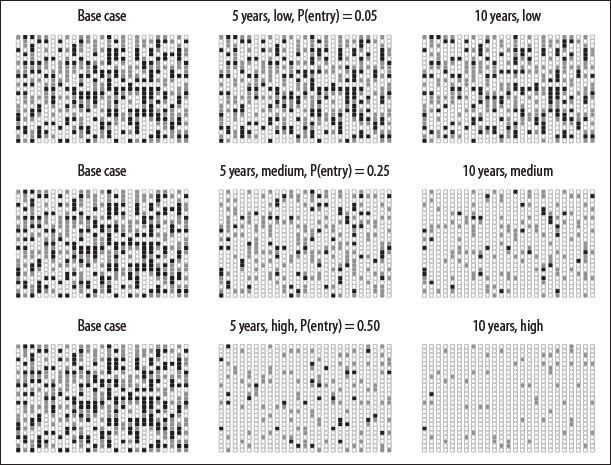

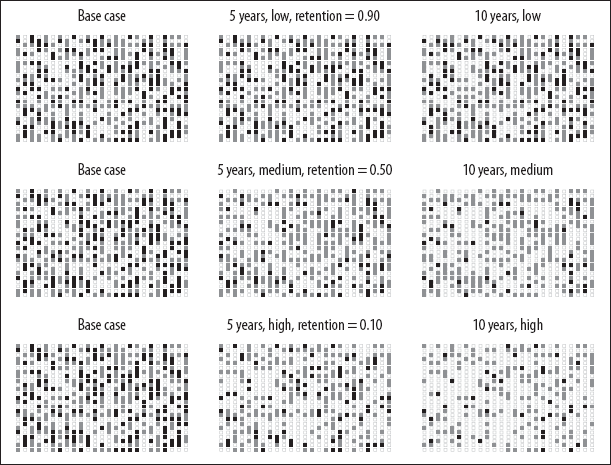

To illustrate how different descriptive characteristics of starfish systems play out in determining outcomes, I will introduce very simple numerical simulations. These simulations are illustrative, not probative; they just demonstrate in a simple formal model how simple changes in system openness can lead to very different dynamics in overall system learning performance.

Imagine a checkerboard, on each square of which there is just one school (for simplicity; I'll relax this in a second). To initialize a scenario, we choose a “school” associated with a unique level of learning for each square as a random number from zero to one. Bad schools (with learning on this arbitrary metric of less than 0.33) are represented by black squares, mediocre schools (between 0.33 and 0.66) are gray, and the better schools (above 0.66) are white. All three of the leftmost graphs show the same base case, with an equal mixture of bad, medium, and good schools randomly distributed over the grid.

What is the dynamic of this grid? Our first thought experiment is that in each year, each checkerboard either faces an entrant or not with the same probability (that is, entry does not depend on the quality of the existing school). If a school does face an entrant, the entrant chooses a random draw from the same underlying distribution of quality as existing schools. That is, we are not assuming that “entrants” are on average better than incumbents for any reason.

The key feature of this simulation is that if the entrant is better than the incumbent, then the entrant replaces the incumbent in that period. The process is then repeated, and in the next period the same thing happens: entrants might come, and if they are better they replace the existing school. I run this simulation forward for ten years.

Figure 6-3 shows the results of this simulation to underscore the central role of openness of a system in improving learning results. In the top row of graphs the probability of entry is 5 percent per year, that is, only one in twenty incumbent schools will face a challenger. When the ecosystem is this closed, the graph changes very slowly, and even after ten years the ecosystem still has many bad schools. This illustrates the consequences of no organizational learning (no incumbents are getting any better) combined with a closed system. This simulation is actually favorable to spider systems, and, as we have seen, many spider systems have essentially zero entry probability (bad schools are not replaced) and little organizational learning.

In the middle row of graphs, all that changes in the simulation is that the chance any given school will face a challenger rises from 5 percent each year to 25 percent each year. Now one sees dramatic changes. The worst schools are much rarer, and even the mediocre schools are visually much less of the population.

Figure 6-3. Open entry accelerates the diffusion of innovations and improvements in school quality.

Note: All assuming zero retention of low-quality schools.

When entry reaches 50 percent per year (which is admittedly very high), then in ten years’ time, bad schools are practically gone, and even very few of the mediocre schools survive the pressure of a constant stream of new entrants.

This simulation is powerful when we think of all the ways we biased against improvement in average learning outcomes through limiting the entry of new schools. After all, in this scenario no school ever improves. In this simple simulation school quality is like eye color; schools are born with it. We also biased against the power of entry because new entrants are not purposive—they don't go after bad schools, they are random. We also biased against entry because we didn't assume that the population of new entrants would be any better than the initial population—I am not building in that, say, “charter” or “private” schools are on average better than public schools, for instance. Nevertheless, just replacing worse schools with better schools cumulatively transformed the entire educational landscape.

The amazing power of starfish systems emerges from the fact that the overall system performance can improve even without any existing organizational structure improving. If one started with a set of schools, then even if no school were able to “learn” how to improve its overall educational performance, the overall system performance could improve over time.

Moreover, this doesn't even require that the new entrants be somehow equipped with new technical knowledge or a formula. In all of the simulations the new entrants took a random draw from exactly the same distribution of productivity of the existing schools—there was no “technological progress” that only the new entrants could take advantage of. They were just like the old guys.

What makes the power of evolution or emergent order or creative destruction work is just that the more productive are more likely to survive and to thrive (that is, take on larger shares of the task). Trial and error alone can lead the overall sector to progress, even with no technological change and even if every school, once launched, congealed and could not improve.

This power of ecological learning is important because, as we saw in chapter 4, organizational learning is often very difficult. After all, successful organizations are often successful because they hit on a formula that matches a particular context and then just perfect themselves at the formula they have and build that formula into the very fabric of the organization. If that formula ceases to work with the context, it is often next to impossible to change the organization's culture—and new organizations come along that embed the new formula into their new culture, and thrive (Barnett 2008).

As I argued in chapter 5, since schooling is not third-party contractible and the socialization of beliefs is an integral and legitimate part of socialization, it has become, in many societies, including societies that are generally free and liberal, politically unacceptable to have completely open entry into basic schooling. It is simply unacceptable to have schools premised on white supremacist ideology in the United States or radical Islam in Pakistan or ethnic separation in many countries. Therefore, the entry process for schools cannot be an open market like the entry process for restaurants or the manufacture of shoes or instruction in piano.6 Schooling is different, and the purely open market is not appropriate as the ecosystem for schools.

On the other hand, the overwhelming tendency is to overcontrol the entry of schools such that the possibility of innovation is precluded, and especially the disruptive innovation that is needed to accelerate progress in learning. That is, when spider systems open up incrementally, the political economy often insists that the new alternatives look exactly like the spider schools in every respect. In particular, rules of entry often perpetuate precisely the kind of input orientation (rather than performance orientation, with openness about how that is done) that stifles the spider system in the first place. For instance, India's recent Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, better known as the Right to Education Act, passed in 2009, while laudable in many respects, acknowledges that the private sector has expanded and essentially become a parallel system to the existing public system as people coped with the dysfunctional public schools. However, the act defines “quality” as inputs and attempts to impose purely input-driven standards on the private schools, even though there is no evidence in the Indian context that input standards produce learning.

While tight regulation of entry based on inputs seems attractive as it “protects” parents and children from “risky” or fly-by-night schools, this is the most dangerous form of the regulation of entry, for two reasons. First, input regulations are almost inevitably controlled by incumbents, and incumbents, whether in the private or the public sector, have every incentive to use entry regulation to thwart entrants. It is a myth that private sector firms favor competition. In a capitalist system one of the first things private sector firms do whenever they can is use regulation to prevent new entrants, to protect their position.

Second, input regulation almost inevitably means input isomorphism. If there is a conventional wisdom about what good schools look like, then this orthodoxy, even if it lacks any grounding in empirical evidence, can block entrants. Input-based orthodoxy is particularly pernicious as it blocks disruptive innovations.

As just one of hundreds of possible examples of innovation that are out there, take the LEAPS Science and Math schools in South Africa. They are based on a particular philosophy of education that involves linkages with the community, tutoring, high expectations of students, and a particular set of core values. But they are also cognizant that to be scalable, the model needs to address the problem that excellent teachers can be expensive and are a key input, and look for ways to maximize the impact of the teachers they have through the innovative use of computers and peer-to-peer instruction. If this model had to wait for the approval of bureaucratic committees, the desire for assured input quality might easily have missed the point of the quality the LEAPS model provides.

Locally Operated—While Embedded

Schools need to be autonomous, but autonomous while embedded in an ecosystem that promotes and supports high performance, which are the aspects of the ecosystem that underlie the next four principles. There is ample evidence that reforms like “markets” or “vouchers” or “decentralization” can work to provide an environment for improvement. But whether can work translates into does work depends on the details. As we saw above, when spider systems are dysfunctional or even value subtracting, then just freeing schools from the burden of the tight coupling into the web of a dead spider can lead to large gains in performance. But the experience with Chile shows that moving to markets alone does not, in and of itself, provide a sufficient dynamic for sustained performance.

The key is to pull apart all of the many functions and activities and allocate those across the system such that the local component of the system provides a constant stream of innovation and new ideas and can use the local nature of the operation of the system for thick accountability (more below), while the national level provides a framework for standards and monitoring and evaluation of performance and the intermediate levels provide support to the local levels. As table 6-5 shows at a schematic level of functions only, not specific activities, the result is neither pure spider nor pure starfish (nor pure in-between) but a hybrid.

By “local” I mean “local” in the sense of your local barber or hairdresser, your local grocer, your local congregation—local as a geographic and social space that forms some type of community. Table 6-6, with its delineation of tiers of government, allows a definition of what is local. Discussions of decentralization that begin from fiscal decentralization across tiers of government rather than from underlying functions can lead to confusion. In most countries of the world a “decentralization” that is a “federalization” of moving responsibility from the national government to states and provinces often just shifts a spider system into a modestly smaller jurisdiction, with no real change. Similarly, the intermediate tier between the “state” and the school—in India this would be a district, or in an urban environment a municipality—often is too large to realize any gain from being local but too small to be responsible for setting curricular standards or handling monitoring and evaluation.

Table 6-5. The key is uncoupling the system and allowing each tier of government (and nongovernment and market) to do what it does best.

Table 6-6. Appropriate allocation of activities will provide a high-quality teaching force.

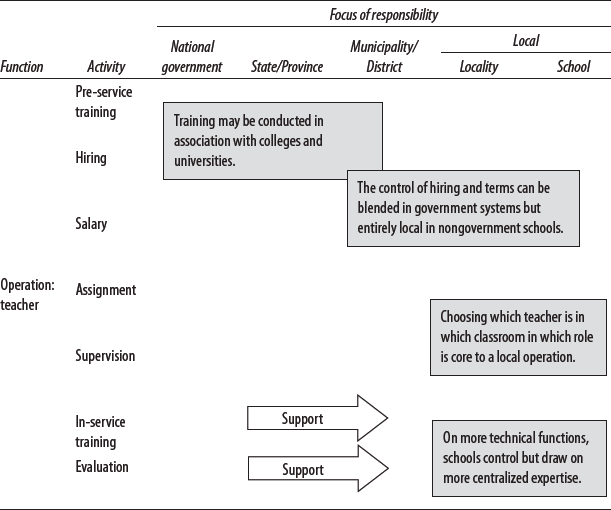

Table 6-6 also makes it clear that there are three distinct functions: setting up the game, providing training and coaching, and the actual playing itself. In an analogy to sport, there is the league or association, which sets the rules and provides the officials and referees that enforce the rules and declare the official times and scores; there are the trainers and coaches, who help athletes do their best; and there are the actual athletes. In using a sports analogy I am not saying there are “winners” and “losers.” Many individual sports with widespread participation, like running or swimming or tennis or bicycling, encourage each individual to do his or her best—within a structure. In the schematic there is a support role, like that of a coach or trainer, which is a role that intermediate tiers of government can provide.

Table 6-6 also makes the most controversial point in the whole book (which so far has been pretty free from controversy—and irony): for local operation to mean anything significant, it must mean that the local level has responsibility for teachers. An enormous amount of the discussion of greater school autonomy or empowerment has dealt only with the operational aspects of the school that don't involve teachers, such as procuring chalk, sweeping the grounds, and fixing the windows. This is not trivial. When spider systems turn dysfunctional but keep responsibility for everything centralized, even the simplest functions are done badly. The movements to push control of operational expenditures to the school level with transparency as to the flows do lead to significant one-off gains. However, if schools are not allowed to choose which teachers will teach, then local operational control is just rhetoric.

Since teachers are the essential component of education, it is worth elaborating on how an embedded starfish system of local operation would work, as this illustrates the mix of local control and technical support. Of course, this description is still schematic and not at the level of granularity and detail—which will depend on context—that an actual plan would be, but it illustrates the major points.7

Obviously, each school would not create its own pre-service training curriculum. Such training would continue to be done at a higher level and provided by a mix of institutions, from dedicated teachers’ colleges to more general colleges and universities.

The key to local control is assignment. One major difficulty with spider systems is that they conflate the hiring process with assignment. In the interests of “quality control,” many systems establish mechanisms for hiring the “best” teachers according to narrow, “thin” criteria, such as scores on a test. Once hired, these teachers are then assigned to schools based on some bureaucratic system such as a points system of preference (often one in which seniority has the most weight). These systems mean that local principals or local school boards or committees have little or no control over who is teaching in their school. A school cannot create a vision and a mission and a sense of being a unique and special place when it cannot control who teaches in the school and in what capacity or classroom.

The assignment function can be either entirely coincident with the hiring function (as in NGO or private schools) or these functions can be distinct. That is, a level above the locality can create the cadre of potential teachers, those who are authorized to be assigned by a local school, while the local schools choose which of those potential teachers are assigned. This approach can create some productive tension between professional and local accountability (discussed below).

In-service training is an example of a mix of local control and support. Each school cannot possibly be expected to create the necessary training for each of its teachers (from potentially pre-K to advanced levels) in each domain (math, science, music, art, social studies, etc.). By the same token, however, top-down control over in-service training can lead to training that is disconnected from the real needs of schools and teachers. With local control, schools can define their training needs and then seek out the training they need from an array of options offered by different producers of teacher training. The budget for this training can be controlled separately from the routine financing of the school so that schools are given adequate incentive to invest in their teachers.

This is not intended to be a detailed blueprint but rather a schematic that illustrates once again the need to pull apart tightly coupled systems, but pull them into pieces that are connected in sensible ways. Local control of the operation of schools does not mean every school for itself; it means allowing maximal local control over those decisions for which local control is most beneficial while embedding each school in an ecosystem of standards and evaluation and providing support.

Performance Pressured

Built into the previous traits of open and locally operated systems is the idea that the system can be performance pressured. Natural evolution describes a pressured system. In evolution, the performance pressure is reproductive ability. Organisms with higher reproductive performance grow in number; those that adapt poorly or not at all to changing ecosystems decline.

Pressure for performance in starfish systems does not lead to everything being the same. The performance-pressured system for animals has produced millions of species, which run the gamut from single-celled bacteria to whales and elephants. The order that includes the insect beetles contains almost half a million distinct species. The surviving species share nothing in common: not size, color, shape, diet, mode of reproduction, or survival strategy. The only thing they share is that they survive the pressure of limited resources and have found some niche in their ecosystem.

The same is true of functionality. Lots of animals swim: salmon swim, dolphins swim, otters swim, ducks swim, penguins swim, jellyfish swim. They all do so in ways that are consistent with the underlying facts about water but have ended up with very different ways of propelling themselves through water. There is no one best way to swim. All that is needed is genetic variation plus performance pressure in the form of higher survival value for better swimmers, and swimming performance “naturally” improves, not because some central agent decided on the best way to swim based on what looks the best but because of performance.

Researchers in Pakistan ran an experiment of choosing some villages in which every child was tested in grade three, and “report cards” for both public and private schools were provided to parents (Andrabi, Das, and Khwaja 2009). This was a massive infusion of information into the system—but without changing anything else. The researchers found four effects, all of which are revealing about the channels whereby information changes the behavior of actors in the system.

First, many of the private schools that were “bad” on the initial report card improved substantially—by, on average, 0.34 effect sizes. One response to performance pressure is to improve.

Second, many private schools that were revealed to be bad just closed. The bad schools in report-card villages were much more likely to close (twelve percentage points) than were either good schools or schools in villages with no report cards.

Third, good private schools that stayed open did not improve by much, though they did lower fees.

Fourth, there was some modest improvement in government schools, but no closures. The learning gains in bad government schools were only at a 0.078 effect size—4.5 times smaller than the learning gains in bad private schools. Clearly, the government schools were less responsive in every way to information provision than were private schools.8

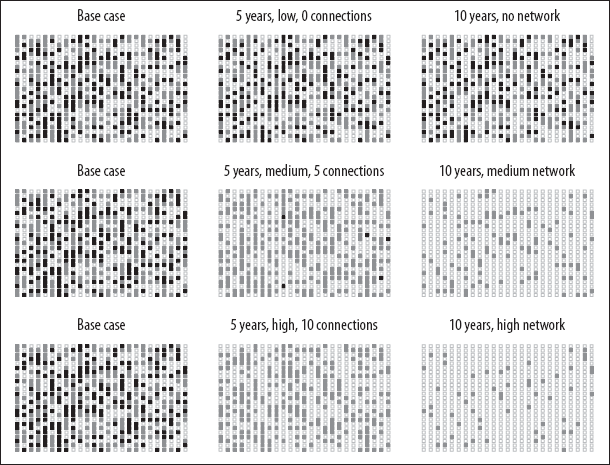

We can simulate the impact of performance pressure using the same evolution of the checkerboard of schools as was used earlier. This time, rather than varying the probability of a new entrant, I vary how easily these new entrants can attract students if they are better. In the earlier example we assumed that the higher learning school attracted all students. In this simulation we vary the incumbent advantage by changing what fraction of students stay in the incumbent school.

The first panel of figure 6-4 shows the evolution of the system when incumbents retain 90 percent of students no matter the performance of the new entrant. In this case, even with lots of new entrants, the average quality of the system stays low over extended periods—ten years on, most students who started out in bad schools are still in bad schools.

The second and third panels show the dynamics as more and more students move to the better school. If the more productive entrants get half the students, the dynamics already improve, with many fewer students in bad or mediocre schools. Of course, if the dynamics reach the level where most students (90 percent) switch to the higher-quality entrant, then the results are better still (approaching those of figure 6-3, where it was assumed 100 percent of the students moved).

Saying a system should be “performance pressured” is meaningful, as it rules out many existing systems that have no learning performance pressure at all, but it doesn't imply there is one single best measure of performance or that “performance” should be reduced to a few or “basic” criteria. Schooling systems are everywhere and always complex and intrinsically political and social arrangements about how children are raised. While this book is very strong on promoting learning, the idea that school performance can be reduced to outcomes on a few standardized tests in a few domains (such as math and reading) is beyond absurd. Citizens as parents care about how their children are treated, they care about the values schools instill, they care about equality of opportunity, they care about lots of different capabilities. And citizens disagree about all these things. Some want schools to teach more basic skills, some want schools to teach students more creativity, some want students socialized into more traditional values of respect for authority, some want schools to teach children to question and think critically.

Figure 6-4. When the incumbent is not pressured (schools retain students even when of lower quality), the dynamics of improvement are slowed.

Note: All assume the “medium” entry scenario of P(entrant) = 0.25 per annum.

In thinking about performance pressure and accountability in systems, there is a basic distinction between “thin” and “thick” accountability (Pritchett, Samji, and Hammer 2013). Thin accountability is a mode of accountability appropriate to a purely logistical task, such as delivering the mail. Everything about a package that is relevant to the post office can be reduced to a few simple bits of information—the address and the mode of delivery. Each agent of a postal service can be held accountable for following the appropriate action, which can be specified by a very narrow set of rules.

But the delivery of most services is much more complex than delivering the mail and is implementation-intensive in that success requires the agents to carry out actions that are based on subtle, often difficult to observe and impossible to make “objective” aspects of the situation. An example here is marriage and matchmaking. Coupling people cannot be reduced to logistics because each person is unique.

The mix of accountability based on information about objective measures of learning performance and based on parental (and student) choice isn't a trade-off relative to current situations—the volume can be turned way up on both. Lots and lots more information about learning performance made publicly available and transparent creates performance pressure. That said, this information should not to be used to manage a school organization as if it were a post office based on this thin information. Rather, the combination of local operation and increased parental choice among alternatives leads to a thicker form of accountability.

Performance pressure has to be built into the ecosystems of basic schooling, taking into account what we have seen through experience.

Choice Needs Information

In a pure choice mode, where money follows the student, performance pressure would come from schools trying to attract and keep students. This may or may not create pressure for better academic performance. If parents have little or no information about a school's performance, particularly how much value added it offers, then choice systems can lead to parents choosing schools based on reputations and social signals about the student body. This runs the risk of competing on ducks. Literally. Since parents are looking for a school where their child will be happy, one strategy is to make the exterior of the building look attractive by painting brightly colored yellow ducks on the exterior. Without any information available on actual student learning, a performance pressure becomes ducks.

High Stakes for the Student Can Improve Performance—but Not Schools

A reasonable person might wonder why, in a book that opens with poor learning performance in some developing countries but high measured performance in East Asian countries, the simple solution isn't for more countries to adopt the “East Asian” model of schooling. This is because there are two key features to the East Asian success in producing high test scores: capable bureaucratic spider systems and high stakes for the student testing. A country cannot simply choose to have an East Asian (Japanese, Korean, Singaporean) quality of administration. It comes from a history—and with a price.

The second feature is high stakes for the student testing. In nearly all high-performing East Asian countries there is a long history (in the case of China, literally thousands of years) of using examinations to determine life chances. Many of these countries promoted widespread basic education but also rationed entrance into university—and especially the top universities, from which the elite was drawn—based on an exam. There is no question that high stakes for the student examinations that are life-determining induces effort—indeed, amazing effort—in improving the scores on those examinations. To the extent that other assessments like PISA or TIMSS are correlated with that skill set, this will show up as impressive average scores.

However, high test performance in high-stakes-for-students systems says little or nothing about the quality of schools, in three respects. First, nearly all examination takers supplement their public schooling with tutoring, and hence their scores reflect the combination of schools and tutoring; it could well be that the school learning is perfectly ordinary. Second, high-stakes examinations induce students to learn what is on the exam—independently of whether that constitutes a complete, or even relevant, education. The examination for choosing national (imperial) civil servants emphasized the ability to write beautifully structured essays on Confucian principles into the twentieth century, which directed enormous intellectual effort into producing better Confucian essays, for good or ill. Third, the outcome needs to be judged on a “per effort” basis: simply making students work harder to overcome mediocre schools and instruction might work, but does not mean on a “per effort” basis this is fair to students.

Parental Choice with High Academic Performance Information and Salience

One key to a performance-pressured system is the creation of standard examinations that are low stakes for students but whose results are published and disseminated at every possible level—school, locality, municipality, state, nation. The constant flow of information about performance increases the salience of academic performance in parental choices.

I am not saying that information about student learning performance should be mechanically used in a way that is high stakes for the school. While I have been consistently avoiding detailed discussion of the U.S. experience with the No Child Left Behind Act because I do not want to get distracted into the hotly charged particulars, let me just state that what I am saying is the opposite of the way in which NCLB was implemented and used. That is, I am proposing that information about performance at the school level be widely disseminated so that it is one element of the choices parents and students make in their exercise of thick accountability. I am against using any single concise set of thin accountability metrics by a top-down authority to manage schools.

I am also aware of all of the complexities of making available average performance on assessments or examinations at the school level. Empirical studies have shown again and again the overwhelming importance of student background as a correlate of performance on formal examinations. Hence, school averages mainly reveal the socioeconomic background of the students in the school. They actually say very little about the quality of the instructional experiences in the school. If schools are recruiting new students based on their published average scores, this can lead them to game the system in various ways, both through explicit cheating, which can be controlled, and through attempting to select the best students into their schools.