CHAPTER FOUR

Uzo Egonu and Contemporary

African Art in Britain

As mentioned in Chapter Two, the opening in 1962 of the Commonwealth Institute and its galleries, particularly the main one, provided an important exhibiting venue for African, Asian and Caribbean artists based in London, as well as their counterparts in other parts of the world. There were two gallery spaces at the Commonwealth Institute, which was centrally located in the heart of London, on Kensington High Street. The main space opened with an inaugural exhibition, Commonwealth Art Today, on 7 November 1962.1 Her Majesty the Queen opened the Institute, at which time she met a number of artists, including Francis Newton Souza. A second space, known as the Bhownagree Gallery, occupying a passageway/corridor, also existed within this modern architectural complex that operated to promote the arts, culture, and other aspects of the countries of the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth Institute hosted a considerable number of important exhibitions, over a period of nearly four decades. These exhibitions included both solo shows and group shows, by artists from, or with significant links to, the countries of the Commonwealth. The inaugural exhibition, Commonwealth Art Today, provided an invaluable series of snapshots of contemporary art practice as it existed across extensive parts of the world and within the capital. For example, Frank Bowling and Aubrey Williams represented Guyana (then known as British Guiana).

Nearly a decade later, the Commonwealth Institute hosted an exhibition of Caribbean Artists in England.2 Again, this was an venture of great importance, offering as it did a substantial and high-profile opportunity for artists with links to the Caribbean, temporarily resident in England, to exhibit alongside other Caribbean artists who had made their homes in the nation’s capital. The exhibiting artists were Althea Bastien, Winston Branch, Owen R. Coombs, Karl Craig, Daphne Dennison, Art Derry, Errol Lloyd, Donald Locke, George Lynch, Althea McNish, Ronald Moody, Keith Simon, Vernon Tong, Ricardo Wilkins, Aubrey Williams, Llewellyn Xavier, and Paul Dash (though he was unlisted).

Like their counterparts from the South Asian countries of India, Pakistan and Ceylon, young artists from across the African continent were settling in London and establishing careers for themselves, often following periods of study at London’s art schools. From the 1950s onwards, these artists, resident in London and elsewhere in the country, were joined by other African artists whose time in London was much briefer and was often linked to exhibitions of their work at venues such as the Commonwealth Institute and Camden Arts Centre. Perhaps the most significant pioneering African artist to settle in London and contribute to the British art scene was Uzo Egonu, born on 25 December 1931 in the Nigerian city of Onitsha. Like Frank Bowling some years later, Egonu came to the UK whilst still in his early teens. He was very much ‘an African artist in the West’,3 as Olu Oguibe described him. Indeed, so acculturated was Egonu to life as a British artist that he was one of the 11 practitioners whose work was sent from London to Lagos for Festac ’77: The work of the artists from the United Kingdom and Ireland. As mentioned earlier, Festac’77 was an international festival of arts and culture from the Black world and the African Diaspora. All of the artists were London-based, and Egonu exhibited in the company of another Nigeria-born artist, Emmanuel Taiwo Jegede, and other artists from the United States and the Caribbean who had made London their home.

Egonu had the distinction of being, as Araeen put it, ‘perhaps the first person from Africa, Asia or the Caribbean to come to Britain after the War with the sole intention of becoming an artist.’4 In this regard, Guyana-born painter, author and archaeologist Denis Williams should perhaps also be considered, his early promise as a painter having won him a two-year British Council scholarship to the Camberwell School of Art in London in 1946. Egonu also takes his place alongside another important pioneering Nigerian artist, Ben Enwonwu (1917 or 1921–1994)5, described as:

One of the most well known African artists to have trained and exhibited in Britain during the period between the wars, Born, [like Egonu] in Onitsha, Nigeria, Enwonwu studied at Goldsmiths, Ruskin College at Oxford and the Slade School of Fine Art at University College London before returning to Nigeria and embarking on an international career in art.6

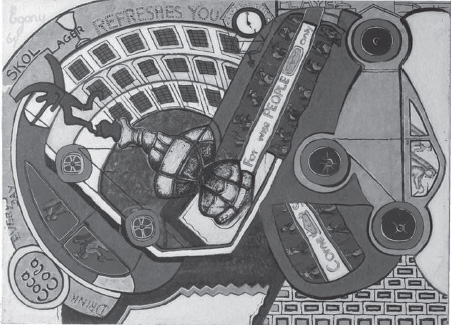

9. Uzo Egonu, Piccadilly Circus (1969).

Egonu was introduced to art at an early age and was painting in Nigeria before coming to the UK. Within a few years of his arrival he had completed his schooling in Norfolk, before going on to study fine art, design and typography from 1949 to 1952 at the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts in London. (This was the art school to which Denis Bowen had won a scholarship in 1946.) Egonu was, from a young age, a prolific and gifted painter and his work consistently reflected a distinctive fusion of modernist influences and aesthetics derivative of his West African heritage. Despite, or possibly because, Egonu left his native Nigeria at such a tender age, the influence, or the memory of Nigeria was a recognisable aspect of his practice. Like other artists from Africa, Asia and the Caribbean, Egonu’s work was in essence a blend of the abstract, the figurative and the representational. As Oguibe observed, ‘For Egonu it was only proper that African artists should not lose themselves in the fiction of a universalist modernism. Instead, they should define a place for themselves within modernism whilst also registering the specificities of their origins.’7 This pronounced reluctance on Egonu’s part to immerse himself uncritically in the language of Modernism had been observed some years earlier. ‘But Egonu resisted the common danger for the African artist of creating an art that was European and derivative without the authentic roots of a personal experience.’8 Such sentiments were, however, not entirely unproblematic. The pathology in which artists of Africa were constantly assessed according to notions of authenticity remained a fiendishly stubborn criterion by which artists were judged.

Egonu had a remarkable ability to render landscapes and cityscapes as compelling and fascinating geometrical configurations, each of his paintings being very different in its representational aspects. In the mid 1990s one curator pointed to the profound range of influences that could be ascertained in Egonu’s work:

Drawn from his studies of African masks, Nok sculpture, Igbo murals, the work of Parisian modernists and a wealth of other sources, Egonu’s lyrical paintings and prints thematically investigate diasporic movement, isolation and exile for immigrants in the West, philosophical ruminations on war, nationalism and other concerns.’9

A quarter of a century earlier, the breadth of Egonu’s practice had been couched in the following terms: ‘Egonu is preoccupied with world affairs and his recent themes reflect a search for peace and security; he has also done a series of paintings of London.’10 In many ways, Egonu’s strength as an artist lay in the abiding integrity of his painting. He was, for over half a century of artistic practice, unswayed by the fashions or indeed the vagaries of the art scene. Olu Oguibe, who authored a monograph on Egonu published shortly before the artist died in 1996, noted this. Referring to Egonu’s practice, Oguibe observed that ‘its greatness lies in the artist’s general disregard for movements and prevailing aesthetic strategies, and in his pursuit of techniques appropriate for his own vision and circumstances.’11

But the artist who could paint scenes from his homeland with such empathy and affection, such as Northern Nigeria Landscape (1964), was the same artist who could, simultaneously, turn his attention to depicting the freneticism, spirit and the decidedly different architecture of London, the city that was home to Egonu for half a century. Not surprisingly, London was affectionately depicted in Egonu’s work, no more so than in paintings such as Trafalgar Square (1968) and Piccadilly Circus (1969). If ever a painting represented the exuberance and frenetic spirit of the swinging 60s, it was Piccadilly Circus (reproduced here), a painting that is a veritable vortex of movement, architecture, transport, and people on the move.

Though Egonu was resident in London for half a century, he remained primarily identified with the country of his birth and early childhood, rather than the country to which he migrated, as a child. This tendency to keep such artists at arm’s length from inclusive notions of British art was counterbalanced by a willingness, desire, or need on the part of artists themselves to maintain a close notional association with the countries and continents from which they had emigrated. On occasion, artists such as Egonu exercised greater traction, or leverage, exhibiting as African artists, rather than as the British artists they plainly were. Nearly a quarter of a century after he settled in London, Egonu was one of a number of artists to be included in an important exhibition of Contemporary African Art held at Camden Arts Centre. This large exhibition was significant for a number of reasons. Firstly, the exhibition’s catalogue (for which Egonu provided the cover illustration, stretching over the front and back cover), repeatedly stressed sentiments such as, ‘The exhibition has been carefully prepared to include as many artists as possible – to the point that it constitutes the first attempt at a comprehensive view of the contemporary African scene.’12 The exhibition had at its core a deliberate and concerted attempt to present the artists as very much occupying a modern world, in contrast to the dominant mindset which tended to regard Africa’s best art as somehow located in a somewhat ancient yet timeless, mythic past.

[V]ery few are sufficiently concerned to look at contemporary works, much less take them seriously. It is sufficient to notice that most books on African art close abruptly after a presentation of the heads of Ife, the Bambara antelopes, the Baule masks, the Fang statuettes, the Kota reliquaries, the Lega ivories […] all the well known examples of ‘good’ African art. As long as we condemn Africa to the past, the numerous exhibitions of traditional art will introduce us to nothing more than a universe of tribal images seasoned in myths – carefully conserved, interpreted and distributed by the Western intellectual.13

Elsewhere in the catalogue, another introduction let it be known that ‘This Exhibition will present the public with its first opportunity to see the work of modern African artists in its full range and variety, from Dakar to Zanzibar and from the Blue Nile to the Reef.’14 This was to be the first of a number of periodic attempts to introduce the work of contemporary African artists to London and British audiences. Each new attempt revisited the above sentiments, in the hopes of disabusing the notion that contemporary art and Africa were somehow mutually exclusive. A quarter of a century after Contemporary African Art, London galleries played host to an ambitious series of exhibitions and other events that went under the banner of africa 95.15 One of the centre-pieces of the project was Seven Stories About Modern Art in Africa.16 The Director of Whitechapel Art Gallery (which hosted the exhibition) wrote in her catalogue foreword that the exhibition

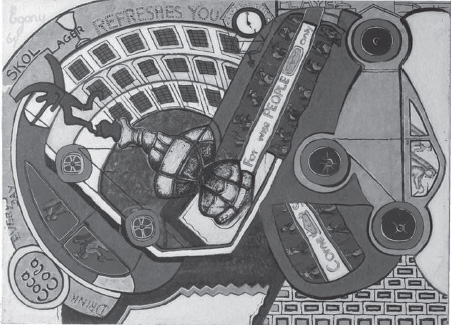

10. Caribbean Art Now catalogue cover (1986).

has been organised with the confidence that, by listening first to the personal viewpoints of distinguished African artists and curators, attention will be directed to the serious achievements of artists, both those working as individuals and those who have contributed to movements.’17

One of the exhibition’s co-curators, Clémentine Deliss, wrote in her introductory essay that when the exhibition was devised several years earlier, it proposed ‘to provide a series of personal interpretations, by artists and historians from Africa, of specific movements or connections which have significantly qualified twentieth-century modern art in Africa.’18 Towards the end of her essay, Deliss opined that ‘In their personal styles, the Seven Stories together display the diversity of artistic expression in the visual arts of Africa in this century, introducing audiences to the artists’ own understandings of their recent histories.’19

A decade later, the whole africa 95 enterprise was reprised as Africa 05. On this occasion, the key exhibition aimed at introducing the work of contemporary African artists to London audiences was Africa Remix.20 The Preface to the Africa Remix catalogue opened with the boast that this was ‘the largest exhibition of contemporary African art ever seen in Europe’.21 In his Introduction, Roger Malbert suggested that, ‘Africa Remix should be thought of […] as an anthology or compilation, serving to introduce a selection of significant artists to a wider public largely unfamiliar with them.’22 The size and scale of the exhibition was clearly important to Malbert, who went on to say ‘One distinction of Africa Remix is that it is the first large-scale exhibition to embrace the whole continent, north and south, from Cairo to Cape Town.’23 Seven years later, another such exhibition took place. We Face Forward: Art from West Africa Today was shown at venues in Manchester during the summer of 2012.24 The exhibition challenged its imagined audience to:

Forget everything you think you know about African art; embrace all that you don’t yet know about the art, culture and creativity of West African artists today. Major new sculptural installations, painting, photography, textiles, video, sound and fashion ask us to consider global questions of trade and commerce, cultural influence, environmental destruction and identity.

Challenging and humorous, curious, noisy, elegiac and electric – this is the dynamism of West African cultures today.25

Predictably, one of the introductory essays in the catalogue for We Face Forward: Art from West Africa Today reprised the stock motivations that apparently lay behind exhibitions of work by contemporary African artists – the twin agendas of countering ignorance and facilitating greater exposure to these artists’ work.

While Manchester’s collections are rich with the history of art and craft from West Africa – the legacy of colonialism – we know almost nothing about the contemporary cultural scene across the Anglophone and Francophone countries of West Africa. We Face Forward: Art from West Africa Today was born out of a desire to remedy this.26

A paragraph or two later, the writers state that

Our most pressing wish was to explore the incredibly diverse and dynamic art being made by artists from West African countries, not as an exhibition of work that is ‘separate’ from the global art scene, or defined through ethnographic or geographic containment, but as a body of work that is actively engaged in shaping and challenging how that world is configured.

During the 1980s, Caribbean Art found itself similarly constructed as a panacea for ignorance of the wider cultural dynamism of the region. Caribbean Focus ’86 set itself up as a model for ventures such as africa 95 and Africa 05. Utilising the admonition, ‘Widen Your Vision, Sharpen Your Focus’, Caribbean Focus took place between ‘March to November all over the country’ and presented ‘music, theatre, exhibitions, education, ideas, dance and debate’. One of the centrepieces of the programme was Caribbean Art Now, which dubbed itself ‘Europe’s first exhibition of contemporary Caribbean art’ and was held at the Commonwealth Institute over the summer of 1986.27 The exhibition’s press release boldly stated, ‘FIRST EUROPEAN EXHIBITION OF CONTEMPORARY CARIBBEAN ART’ and opened with

The western world has seen remarkably little of contemporary art from the Caribbean. The Commonwealth Institute’s major exhibition, ‘Caribbean Art Now’ is therefore both an important artistic event and an opportunity for international exposure for the artists concerned. 28

Another significant feature of Camden Arts Centre’s 1969 exhibition, Contemporary African Art was that it reflected the extent to which London art schools were, in the 1950s and 60s, the destinations of choice for many young African artists wishing to pursue their studies. Catherine Lampert reiterated this important factor in her foreword for the Seven Stories About Modern Art in Africa catalogue. ‘Since the fifties, ambitious young African artists have arrived at foreign art schools; those from Anglophone countries were linked especially to the Slade, the Royal College and Goldsmiths.’29 Many of the artists gathered together for the Contemporary African Art exhibition had associations with London arts schools.

Several years after the Camden Arts Centre exhibition, Egonu was still being regarded as a painter of the African continent. Together with Cyprian Shilokoe, Tito Zungu, Louis Maqhubela and Ahmed Louardiri, Egonu was a prizewinner in an annual competition, by then in its fifth year, run by African Arts magazine. The announcement of the 1972 prizewinners formed the basis of one of several features on Uzo Egonu that appeared in the magazine over a span of several years. This piece was in the winter 1973 issue.30 A work by Egonu, Hair Plaiting, appeared on the cover of the magazine. A number of colour and monochrome plates of work by the artists illustrated the piece. At the front of the magazine the feature was introduced as:

Our fifth annual competition is again proof of the abundant and diverse creative talents to be found in Africa today. While the individuality of each artist is displayed in the subject matter, style and media, all of the prizewinners are nonetheless united by elements which mark each work as distinctly African.31

About Egonu, the text stated (in part):

Uzo Egonu will be known to readers of African Arts from the illustration of his prizewinning painting that achieved the distinction of first prize in the BBC African Art Contest, as was described by George Bennett in African Arts, Volume 5, Number 1. He [Egonu] is now living in London and during the last ten years has built up a major reputation as an artist in Europe. He has had a series of one-man showings in London and other British towns – Leicester, Brighton, Edinburgh and Stroud – besides having made a large number of contributions to group exhibitions in major galleries such as the Royal Institute, and exhibitions such as the Camden Exhibition of African Art.32

Whilst a particularly nuanced attachment to the land of his birth could be discerned in much of Egonu’s practice, he was at the same time somewhat detached from his homeland, as evidenced by a sentiment in a feature on him that appeared in African Arts magazine in 1973. ‘My other ambition is to be in Africa one day, where I will be very much involved with others making vital contributions to solving problems of contemporary African art.’33

As alluded to in the previous two chapters, the 1960s saw the entrenching of exclusionary and somewhat discriminatory attitudes towards Britain’s Black artists. Their apparent pointed exclusion from mainstream exhibitions informed a need on the artists’ part to come together for the purpose of mutual support. In his Egonu monograph, Oguibe summarised this moment, particularly as it related to the artist.

While the Whitechapel Gallery’s annual ‘New Generation’ exhibitions between 1964 and 1966 predictably excluded non-white artists, intercultural fringe and avant-garde groups such as Signals initiated and ran their own independent events and shows. The Indian Artists Group and later, the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM) sprang up alongside community and political organisations. Although Egonu operated largely outside these developments – he later flirted with CAM and was a founding member of a short-lived African parallel – his career gained momentum through them, especially from 1964 onwards.34

The prospect of Egonu joining CAM is truly tantalizing. Had he become an active member, his involvement would have made CAM a broader cultural initiative centred on artists of the African Diaspora, more so than the pronounced Caribbean framing of the movement. CAM was an important and influential cultural initiative, centred on the work, the dialogues, and interconnectedness of a number of key Caribbean-born writers and artists of the 1960s and 1970s. CAM began in London in 1966, reflecting the extent to which London, (as mentioned in relation to a number of the artists exhibiting in the Camden Arts Centre show of 1969), had become an important destination and focal point for ambitious, creative people from the Caribbean and countries in Africa and South Asia. At its core, CAM was a forum for the exchange of ideas relating to the role, and the work, of Caribbean-born writers, artists, scholars and activists.35 Barbadian doctoral candidate Edward Kamau Brathwaite and Trinidadian publisher John La Rose were responsible for the formation of CAM. Anne Walmsley observed that ‘Brathwaite and La Rose each knew and admired the other’s poetry. When they met they found each other to be nurturing a similar idea: an organization of Caribbean writers and artists.’36 Amongst the influential body of Caribbean writers, visual artists, poets, dramatists, and cultural/educational activists associated with CAM were Ronald Moody, Aubrey Williams, Errol Lloyd, Andrew Salkey, as well as its initiators, Edward Kamau Brathwaite and John La Rose.

The early to mid 1960s were heady days for the people of the Caribbean. Cuba, the predominantly Spanish-speaking giant of the Caribbean, had emerged from a violent, protracted revolution that culminated in 1959 with the establishment of a radically altered country, founded on socialist, and, subsequently, communist ideals. Thereafter, the political and cultural complexion of the entire region was transformed. Two of the Caribbean’s largest English-speaking countries, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago became independent in 1962. Barbados followed a few years later. What would independence mean for the peoples of the region, including its artists, poets, novelists, and thinkers? What role(s) could such individuals play in contributing to the lives of the region’s people? What role(s) could the artists of the region play in the enterprise of nation building? Should the artist remain at arm’s length from the new governments that were taking power across the islands and countries of the Caribbean? To these questions were added other, equally pressing concerns. How could the artists and writers of the region best establish themselves in the challenging environments of cities such as London? How could they contribute to the arts, culture, and literature of the country to which they had migrated? What should be the concerns of the Caribbean artist? In the light of seismic changes in the region, how could Caribbean history be understood, or reinterpreted? Looming large over these questions was the perhaps inevitable consideration of what the specificities of Caribbean art and identity were. Such were the concerns and questions that concerned and challenged those associated with CAM.

A hugely important consideration for CAM was the way in which it was, remotely, able to contribute to notions of Caribbean art. In the region itself, artists were grappling with this weighty issue, and the Caribbean artists living in London during the 1960s and beyond were able to make significant contributions to the debate through CAM activities. In the introduction to her essay ‘The Caribbean Artists Movement, 1966–1972: A Space and a Voice for Visual Practice’, Anne Walmsley, herself deeply involved in the development and work of CAM, emphasised CAM’s importance in words that resonate with the themes of this book.

I can’t remember when I last felt so proud as I do tonight, catching a glimpse of Caribbean art,’ said Aubrey Williams in London in June 1967, to a roomful of fellow artists, writers, critics, actors, musicians, students, teachers, housewives, and other variously employed people. Like Williams, most were from a Caribbean country recently independent from British colonial rule; others were from West Africa, Australia, and other Commonwealth countries, or from Britain. They had just seen Ronald Moody show slides and comment on his sculpture; Althea McNish on her fabric designs; Karl ‘Jerry’ Craig, and Errol Lloyd on their paintings. This ‘Symposium of West Indian Artists’ had been organized by the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM). Never before had these artists had a chance to share their work with each other, and with fellow Caribbean viewers of their work.37

The artists involved with CAM had created for themselves an invaluable forum of support and the exchange of information and ideas about their practice. According to Brathwaite:

[CAM] was to be essentially an artists’ co-operative. Our primary concern was to get to know each other and each other’s work and to discuss what we were individually trying to do as frankly as possible, relating it, whenever this seemed relevant, to its source in West Indian society.’38

A measure of CAM’s success could be gleaned from Brathwaite’s statement that:

It was clear from the outset that [CAM] was something that these artists had been hoping and waiting for. News of the group spread rapidly along the grapevine; and from seven the Movement grew to twelve to twenty and by February 1967, when we held our first public meeting, we were fifty strong and had an audience of over a hundred.39

But CAM also set itself the task, or agenda, of dialoguing with like-minded individuals from beyond the Caribbean. Consequently, in his text on the origins of CAM, Brathwaite cited its interactions with key personalities such as Ulli Beier, who had an important role in developing literature, drama and poetry in Nigeria, and James Ngugi [Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o] ‘the well known Kenyan novelist.’40

Furthermore, the journal Savacou was started as a literary vehicle for CAM, enabling literary, scholarly and artistic contributions, as well as CAM’ activities in Britain, the Caribbean, and elsewhere in the world to be documented and given published form. An indication of Savacou’s longstanding commitment to nurturing, supporting and celebrating Black visual artists and other cultural activity can be elicited from a sentence written by John La Rose and Andrew Salkey in the Preface to Savacou issue 9/10: ‘At the time of writing, the most recent medium session, held at the Keskidee Centre, on Friday 10th March 1972, was A Tribute to Ronald Moody, a historical exposition, illustrated with slides, of Jamaican sculpture, arranged and presented by Errol Lloyd, the Jamaican painter.’41 Artists such as Williams and Moody were able to make important contributions to Savacou. Ronald Moody was responsible for the Savacou motif, Carib War Bird, which appeared on the magazine’s flyleaf. The motif was instantly recognisable as Moody’s work, as it closely reflected and referenced his own Savacou (1964) – both the maquette and the public sculpture itself, located on the campus of the University of the West Indies Mona Campus in Kingston, Jamaica. (A press photograph of Moody, standing alongside the work, is reproduced in this book). The Savacou issue referred to above featured a cover illustration by Williams, Jaguar (1972).

During the late 1960s CAM held a significant number of exhibitions at venues across London and indeed, beyond the capital. Artists such as Williams, Moody and Errol Lloyd maintained a familiar presence in such exhibitions. Other personalities committed to contributing included Althea McNish, Art Derry and Karl Craig. The exhibitions took place at venues as diverse as the Theatre Royal, Stratford, the West Indian Students Centre, and the House of Commons, Westminster. Several CAM-related exhibitions took place alongside its conferences held at University of Kent at Canterbury, where Anne Walmsley, a key figure in the history of CAM, earned her doctorate. Reflecting on the success and significance of CAM’s first conference in particular, Brathwaite recalled, ‘[The] cosmopolitan aspect of CAM was most brilliantly in evidence at our first Conference on Caribbean Arts held residentially at the University of Kent over the weekend September 15–17 [1967]. Over ninety people attended.’42

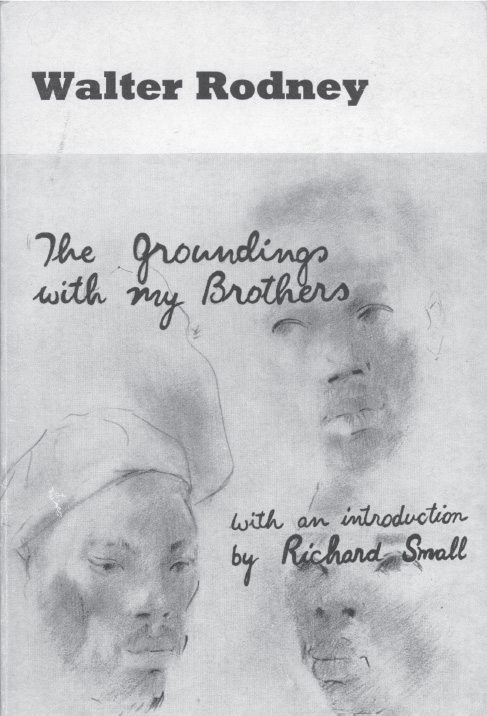

11. Errol Lloyd, The Groundings with my Brothers book cover (1969).

Born in Jamaica in 1943, Errol Lloyd was one of the younger Caribbean artists associated with CAM. A painter and illustrator, Errol Lloyd has for a considerable number of decades been a staunch advocate of the advancement of Caribbean art in the UK. To this end, he distinguished himself, as indicated earlier, as a friend and supporter of artists such as Ronald Moody. Lloyd came to London as a young man of just 20 years of age, for the purposes of pursuing a career in the law. Switching interests, he subsequently had a substantial and distinguished career as an artist, book illustrator, writer, editor and arts administrator. He was for a considerable period of time involved with the Minority Arts Advisory Service (MAAS), an early incarnation of official attempts to nurture British-based ‘minority’ artists or otherwise attend to their needs and agendas. Similarly, Lloyd was for a time editor of Artrage magazine, the organ of MAAS that was published for the best part of 15 years, from the early 1980s onwards. Within Artrage and in other forums, Lloyd reflected, with great clarity, on the practice and conditions of Black artists in Britain.

A self-taught artist, Lloyd provided the cover illustration for an early edition of Walter Rodney’s seminal work, The Groundings with My Brothers, first published by Bogle L’Ouverture in 1969 and reprinted in the mid 1970s, a number of years before Rodney’s assassination. The illustration depicts the faces of several Black men, sensitively drawn, exuding a gentle humanity but simultaneously a steely determination that hinted at the book’s noteworthy contents. Complementing the deceptively simple pencil drawings was the title of the book (together with a reference to the book’s introduction) reproduced in the style of handwriting, as if to emphasise the singular way in which the book contained, quite literally, messages from Walter Rodney, one of the African Diaspora’s most original and important academics, thinkers, writers and activists.

Gifted with an ability to capture likenesses in a range of creative and engaging ways, Lloyd has been responsible for a number of portrait commissions of leading Black and Caribbean males who have excelled in their respective fields over the course of the twentieth century. These portraits include Sir Alexander Bustamante (1884–1977), who together with Norman Manley was the chief architect of Jamaican independence and the founder of one of the country’s main political parties, the JLP (Jamaica Labour Party); Sir Garfield Sobers (b. 1936), the legendary Barbadian cricketer; John La Rose (1927–2006) the Trinidadian intellectual, campaigner, activist, trades unionist, publisher, poet and, as mentioned earlier, one of the initiators of CAM; C.L.R. James (1901–1989) also a Trinidadian, the hugely important historian, writer, theorist, and journalist; and Grenadian David Thomas Pitt (Lord Pitt of Hampstead, 1913–1994), the renowned medical practitioner, politician, and campaigner.

By the mid 1970s, those artists and writers closely identified with CAM were pursuing their interests in other directions, though they remained faithful to their visions and agendas of fostering the integrity of their respective practices. They remained in close contact with each other and this contact resulted in a number of initiatives and was reflected in many others. One particularly fascinating event, which brought together Williams and Lloyd, in the company of other artists, a number of whom were significantly younger, was a forum titled ‘Seeking a Black Aesthetic’. The event took place during what was to be the last of four open exhibitions organised by Creation for Liberation, the cultural wing of the Race Today Collective, of which Darcus Howe was the figurehead and indeed, editor of Race Today, the Collective’s publication. The open exhibitions took place during the summer months of 1983, 1984, 1985 and, finally, 1987. They were held in a variety of venues in Brixton and 1987 was the second year in which the exhibition was held at St. Matthew’s Meeting Place. The Creation for Liberation open exhibition had, that year, been selected by several artists, including Chila Kumari Burman and Eugene Palmer. Discussion events related to the exhibitions were a regular feature of these undertakings and in 1987 it was the elder statesman-like Aubrey Williams who was approached to stimulate a discussion on the selected work and issues relating to the then practices of Black artists in London. Anne Walmsley concluded her essay on CAM with a paragraph on the significance of the event.

In 1987 Williams addressed and Lloyd chaired the forum ‘Seeking a Black Aesthetic,’ which accompanied ‘Art by Black Artists,’ an open exhibition in Brixton organized by Creation for Liberation, the cultural wing of the Race Today Collective. Twenty years after CAM began, the artists showing work and attending the seminar were markedly different in their sense of identity, in their direction, and concerns from those in CAM. They included Sonia Boyce, Chila Kumari Burman, [and] Keith Piper: […] all born in Britain of people who had come from the Caribbean, Africa, or from Asia, technically British, but consciously ‘black’ in self-image and visual practice. In Britain, at least, the concept of a Caribbean artist and the need for a Caribbean aesthetic was already outdated and gone. But, interest in the work of the artists in CAM and in CAM itself, especially in what it gave to its visual artists and what it gained from them, is alive and well.43