CHAPTER FIVE

The Earliest Black-British Practitioners

As stated at the beginning of Chapter Three, the 1970s was, in so many ways, a critical bridge, or decade of transition. In addition to the reasons already posited, the 1970s was the decade that saw the emergence and establishment of a new peer group of painters and sculptors, younger than the pioneering generation of Moody and Bowling, but older than the body of practitioners that was to emerge during the course of the 1980s. These artists were in almost all instances brought up in this country, their education culminating in first or second degrees from British art colleges. Amongst this new generation of artists were painters Saleem Arif, born in Hyderabad, India; David Medalla, born in the Philippines, and Caribbean-born artists such as Winston Branch (St Lucia), Denzil Forrester (Grenada), Tam Joseph (Dominica), George Fowokan Kelly and Eugene Palmer (Jamaica), Althea McNish (Trinidad) and Bill Ming (Bermuda).

Born in 1947, Tam Joseph came to London at the age of eight, eventually going on to fractious, unsatisfactory periods of study at London art colleges in the late 1960s. He has, since the end of that decade, maintained and developed his practice as a visual artist and sometime sculptor. This makes him, on the one hand, too young to be linked to major figures of Caribbean and African art who made London their home in the decades immediately following the end of World War Two. For example, Ronald Moody was born in 1900, Aubrey Williams in 1926, Frank Bowling in 1936 and Uzo Egonu in 1931. In time, these artists came to be respected as elder statesmen, but Tam Joseph was too young to be included in their number. But Joseph’s age, on the other hand, makes him too old to be properly linked to the fiery, boisterous young Black artists, typified by Keith Piper (born 1960 in Malta, and not in Britain as is frequently and erroneously claimed) and Donald Rodney (born 1961) whose brand of ‘Black Art’ emerged in Britain in the early 1980s. Quite possibly, it is for this reason that Tam Joseph is very much his own man, his own painter, standing somewhat askance from the typecasting beloved of the art world.

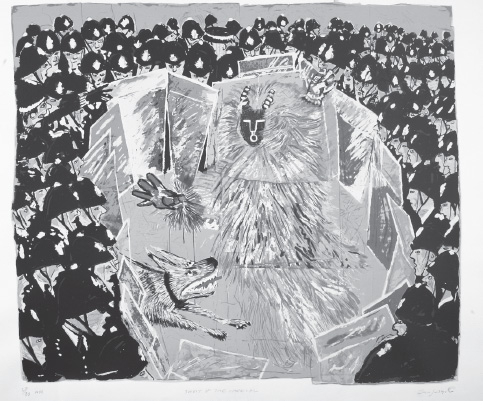

12. Tam Joseph, Spirit of the Carnival (1988).

Whilst Joseph’s oeuvre has been somewhat eclectic compared to the practices of other artists discussed in this book, he has nevertheless, in his time, contributed a number of memorable paintings that locate themselves at the centre of social and political commentary, often doing so in ways that reflect the artist’s characteristic wit, humour, cynicism and perceptiveness. Typical in this regard are paintings such as Spirit of the Carnival and UK School Report, both works dating from the early to mid 1980s. The latter piece, sub-divided into three portraits, shows the passage of a Black youngster through time and the British non-education system. Though unambiguously witty, the painting effectively addresses the miserable experiences of many Black youngsters at school. In the first portrait, the neat and tidy lad is noted as being ‘good at sports’. In the second portrait, the best that his teachers can say about him is that he ‘likes music’. The third is inevitable: a few years of under-achievement at school have put him on the wrong side of society and now he ‘needs surveillance’.

If a Black boy is prejudicially labelled ‘Good at sports’, that child is linked to that almost primeval strand of racism that frequently suggests and sometimes insists that Black people are more physical in their abilities than they are intellectual; that whatever skills they possess lie not in any intellectual capacity, but in their physical attributes. UK School Report lamented the ways in which the educational aspirations of so many Black-British school children have been choked off, in favour of supposedly inevitable athletic prowess or excellence. Though the painting is about the often frustrating and negative experiences of Black boys in the British school system, UK School Report also serves as a general commentary on the often-compromised positions of Black people in Britain. Whilst the red, white and blue colours used in the painting clearly evoke, or reference, the Union flag of Great Britain, it is perhaps the painting’s compartmentalising which gives it its greatest social relevance. The three portraits reflect a profound inability of the youngster to avoid or escape being compartmentalised by his teachers. This in turn reflects, or points to, an equally debilitating inability of many Black people in Britain to effectively function outside of societal constraints and prejudices.

Like Vanley Burke’s photograph of the gathered throng discussed in Chapter Three, UK School Report points to the extraordinary extent to which the culture of Rastafarianism had found its way into the lives and the affections of young Black Britain as it came of age in the mid to late 1970s. The dreadlocked hair of the boy in Joseph’s painting exists as a marker of disaffection, alienation, and more positively, resistance. By the mid to late 1980s, Rastafarianism, and its attendant dread culture had loosened its grip on Black Britain, and other forms of music besides reggae, and other forms of counter-cultural positioning were beginning to reflect the identities of Black youngsters. UK School Report in that sense reflects both a moment in time for Black Britain, and an ongoing marker of the formidable societal constraints placed on Black people in Britain.

As mentioned in Chapter Three, what one journalist had described as the ‘deteriorating racial situation’1 took a particularly vehement turn when violent disturbances involving Black youth and the police erupted at the annual Notting Hill carnival of 1976. The carnival of that year had seen a dramatic escalation in the numbers of police officers assigned to patrol the event, and it was perhaps of little surprise when simmering tensions between the police and Black youth erupted as they did. The effective swamping of the Notting Hill carnival by large numbers of police officers, and the attendant feelings of intimidation felt by some carnival-goers was memorably captured in a key work by Tam Joseph, Spirit of the Carnival within a few years of the cataclysmic events of 1976.

Tam Joseph’s Spirit of the Carnival is an important work that reflected the experiences of those on the receiving end of state-sanctioned, police-orchestrated violence and intimidation. The 1984 work is a poignant, piercing commentary on the seemingly ever-increasing, ever-conspicuous police presence at the annual Notting Hill carnival, though the events of 1976 lay behind its making. The painting depicts a lone masquerader being penned in on all sides by a menacing sea of riot-ready police officers. On all sides of the figure, police with riot shields advance on the carnival reveller, as if seeking not to merely contain or arrest him, but to silence and obliterate him. For good measure, a ferocious police Alsatian strains on his handler’s leash, snarling at the masquerader, having previously drawn blood. And yet, the solitary masquerader is resilient, unbowed, unintimidated. In the face of this relentless hostility and aggression, the reveller continues to play mas.2 It is this spirit of resilience and fortitude that enables the masquerader to embody ‘the spirit of the carnival’.

The work (here illustrated in its print version) is seen from something of an aerial perspective, as if the viewer is somehow slightly elevated above the scene and is thus given a vantage point, to see the police brutality and intimidation that is either hidden from plain view, or has become so normalised as to be almost mundane and less visible. But the painting simultaneously celebrated Black cultural and political resistance and resilience. The body – be that body collective or individual – can be attacked and wounded, perhaps even mortally so. But the spirit, when strong, is unbreakable. The painting also effectively functions as commentary on the ways in which carnivals (and by extension, Black people themselves) are regarded within much of the British population and mainstream media as being synonymous with criminality. Each year, media reports of Notting Hill Carnival centre on, or are accompanied by, tallies of alleged criminal incidents, carrying the unambiguous implication that where and when Black people gather in numbers, criminality, delinquent behaviour and trouble of the most extreme kind are never far away, and that only the presence of overwhelming numbers of police officers can deter troublemakers or maintain law and order.3

Another artist born in the Caribbean was the painter Winston Branch. Born in 1947, he achieved notable levels of success and exposure during the 1970s. He attended the Slade School of Fine Art in London in the late 1960s, graduating in 1970. A few years later, he was a recipient of a prestigious DAAD Fellowship, from which came one of Branch’s most substantial catalogues. Further recognition was to come, in 1979, when the Arts Council bought one of Branch’s paintings for its collection.4 Branch had a number of other paintings acquired for public collections, including West Indian (1973), Yellow Sky (1970), Ju-Ju Bird (1976), and Ju Ju Bird No.2 (1974).

Though Branch has yet to be the subject of substantial critical attention, a very useful and notable feature on the artist appeared in the magazine BWIA Caribbean Beat, November/December 1995. In it, the writer reflected that

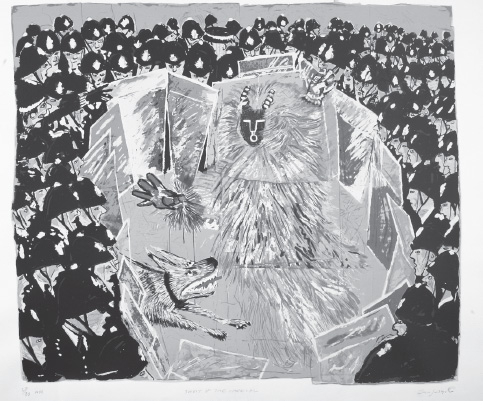

13. Winston Branch, West Indian (1973).

after a very brief stint as a portrait painter in his early days, his work is now purely abstract. Art critic Carlos Diaz Sosa describes his paintings as ‘abstract canvasses in cool, cloudy colours that have a quality which allow the viewer to explore the depths of the mind. Branch also uses paint like a symbol, a purely aesthetic language, an illustration of spirit.5

Branch’s paintings were often strange, and strangely compelling works, which critics sometimes struggled to describe. During the 1970s his paintings were frequently rendered in the form of a triptych. The central rectangular panels, the most painterly of the three, were invariably flanked on either side by more frugal, but no less dramatic panels. The flanking panels – similarly rectangular but slightly narrower in width – often contained seemingly abstract marks, determinedly made, against an imposing background of black that worked well in their endeavours to counterbalance the central panels of these triptych paintings. These black backgrounds effectively create an impression of organic, natural forms – plant life and such – dramatically depicted against the night sky.

In 1978, Branch was the subject of a feature in Black Art: an international quarterly.6 A work of Branch’s adorned the cover of the magazine, in addition to which two page-wide reproductions of his paintings were included in the appreciation. Several substantial photographs of the artist at work in his studio also embellished the text. The writer, David Simolke, offered the view that ‘A momentary glance gives a viewer the feeling that little compositional variation exists in Winston Branch’s series of monuumental works. Each painting is dominated by tripart modular units.’7

Whilst Branch is frequently associated with non-figurative painting, his work West Indian stands out as a marked exception. Against a background that was perhaps reminiscent of elements of colour field painting, Branch painted a portrait of a Caribbean man, casually dressed, wearing a distinctive pink bobble hat on his head. The gentleman in question seems very much at home amongst the assortment of colours and shapes and it appears as though he is leaving one room, the walls of which are colourfully decorated, and entering another, even more flamboyantly decorated space. The bobble atop of the West Indian’s hat appears to be centred by the lintel under which he is emerging. Though the figure is in some respects frugally presented, being rendered in Branch’s own painterly manner, there is nonetheless, an enormous sense of persona about the character, and his workaday, yet stylish appearance casually but absolutely, evokes the spirit, dress sense, visual culture and sensibilities of the early 1970s.

Like a number of Black artists discussed in this book, such as Frank Bowling and F N Souza, Branch made his home in the US, a country perhaps more receptive to what artists such as these had to offer. In 1973, early in his post-college career, he undertook a residency at the famous, historically Black centre of learning Fisk University, in Nashville, Tennessee. Out of that came an exhibition titled The Recent Paintings of Winston Branch, shown at the university’s Carl Van Vechten Gallery, 14 October – 9 November 1973.

Born in Grenada in 1956, Denzil Forrester was one of only a few Black artists to gain an MA in fine art (painting) from the Royal College of Art in the early 1980s. For several decades, he worked out of a studio in Islington Arts Factory, Holloway, North London, from where he produced some of the most arresting and distinctive painting by any artist of his generation. Historically, Forrester took as his subject the twin themes of reggae/dub dance hall and the music, sights, sounds, and movement of carnival. At times, his work touched on other themes, such as deaths in police custody. His canvases – often large, oversize affairs – ranged from dark, brooding and sometimes menacing works, through to vivid, liberated paintings that resonated with bright and vibrant colours. Sometimes, the scenes he depicted were located in low light, almost tomblike or nocturnal environments. On other occasions, much like carnival itself, Forrester took the focus of his attention to the streets, allowing the sun and copious amounts of light into his paintings. In the words of art critic John Russell Taylor ‘The something that Forrester’s paintings are about is distinctive and unmistakeable. From the time when he first encountered the clubs, their dancing and their dub music, they have provided the basic scene for his large paintings.’8

Like Joseph and a number of other Black-British artists, Forrester painted consistently from the late 1970s onwards, his work being featured in a number of exhibitions, both solo and group, from the early 1980s onwards. In this regard, one of his most significant exhibitions was Dub Transition: A Decade of Paintings 1980–1990, which was originated by Harris Museum and Art Gallery and toured to venues in Newcastle and Lincoln. Forrester benefited from a Rome scholarship and a Harkness scholarship, which took him to New York for a period of time. These scholarships gave Forrester opportunities to develop his practice, though he maintained his interest in, and attachment to, the themes mentioned earlier. Publicity material relating to one of his exhibitions stated that:

14. Denzil Forrester, Police in Blues Club (1985).

Denzil has evolved a style which combines the expansive vivacity and glowing colour of his Caribbean roots with a highly effective translation of traditional and modernist European painting. The staccato fragmentation of forms, and dynamic jagged planes which articulate compositions like Carnival Dub and Night Strobe suggest the influence of Italian Futurism, and of German Expressionist painters such as Beckmann.9

Perhaps one of the most important features of Forrester’s work was the way in which, inadvertently perhaps, it created a series of historical documents related to the making of Black Britain. The late 1970s and early 1980s saw the burgeoning of the British sound system – mobile, counter-cultural reggae enterprises characterised by dub music, MCs, DJs, and fiercely partisan followings of young Black people, primarily males. The clubs and other venues in which sound systems operated were graphically depicted in Forrester’s paintings. Similarly, much like Spirit of the Carnival, Forrester’s paintings captured the tension and the menace of the intrusive and unwelcome policing that was often a feature of how society viewed Black cultural expressions, particularly those influenced by Rastafari and the attendant ‘dread’ lifestyle. In his painting Police in Blues Club (1985), (reproduced on page 81) Forrester depicted a club scene, complete with prancing revellers and carousing youth. The painting’s unsettling elements took the form of two motionless police officers, positioned in the background of the painting, silently and with no apology conducting surveillance; the embodiment of menace. Places and spaces in which Black youth could gather, to be themselves, and to express themselves, were few and far between. But Forrester was able to illustrate that even the blues club, beloved of so many alienated Black youth was, or could be, contested territory.

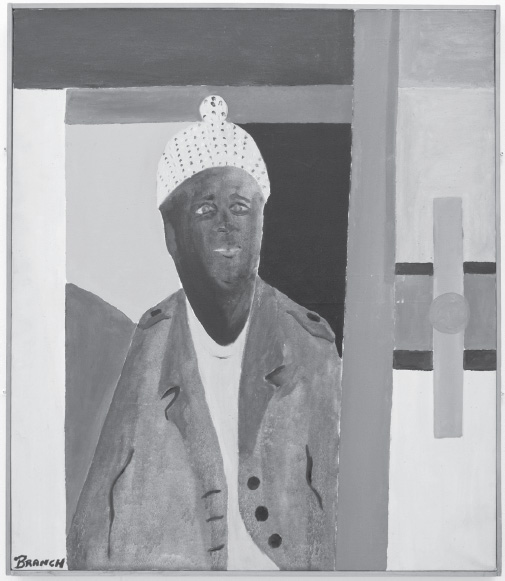

15. Eugene Palmer, Our Dead (1993).

Painters such as Joseph, Forester and Eugene Palmer were new kinds of Black-British artists. Though they were all born in the Caribbean, their upbringing in Britain meant that, alongside the Black diasporic influences they laid claim to, their work also reflected the British visual culture they were a part of, and of which they availed themselves at the art schools they each attended. This duality was observed by one critic, who offered the view that, ‘Denzil’s respect for tradition is a manifestation of the will to find an identity within two cultures, Afro-Caribbean and European, for both have played a vital role in his process of maturing as an artist.’10 This impulse of Forrester’s towards synthesis was something shared by a number of other artists, albeit a synthesis that was, on many occasions, overstated by critics.

Eugene Palmer was another painter who emerged into practice during the period of the late 1970s to early 1980s. Born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1955, he completed an Art Foundation course in Birmingham in the mid 1970s, before going on to secure a BA (Hons) from Wimbledon School of Art in 1978. This was followed, a few years later, by other qualifications, including an MA in painting from Goldsmiths College, in the mid 1980s. A significant period of solo shows then followed, at venues such as Bedford Gill Gallery (which was to be the venue for Yinka Shonibare’s debut solo exhibition the following year), 198 Gallery, and the Duncan Campbell Gallery, a commercial gallery with which Palmer maintained a relationship for a number of years. In the late 1970s Palmer’s work was twice included in The New Contemporaries, and his paintings were included in a number of group exhibitions, including Caribbean Expressions in Britain in the mid 1980s and, a couple of years later, Black Art: Plotting the Course, which looked at the nature of Black artists’ issue-based practice in the closing years of the 1980s.

Palmer’s earliest works were excursions into the terrain of form, colour, composition and shape – non-figurative practice. In time, however, Palmer moved towards figuration, firstly in a fairly loose form, but increasingly, over the years, towards a tighter, more pronounced and explicit type of highly figurative painting. Within his work of the late 1980s, Palmer offered absorbing assessments and interpretations of Britain, Empire, history, and Black identity. As such, his practice was reflective of his own background, having been born in Jamaica at a time in which the island was, along with others in the Caribbean, a Crown colony. Within seven years of Palmer’s birth, Jamaica was to secure its independence, but the links with Britain – political, sporting, cultural, amongst others – would continue through the artist’s lifetime, albeit in changing forms. To this end, the image of the British flag figured time and again within Palmer’s paintings of this period.

One of the most interesting developments in Palmer’s work came in the early 1990s, with the introduction of classical elements into his painting. This intriguing juxtaposition of Black people as subject matter and the employment of classically derived aesthetics resulted in a new body of work that was wholly unique amongst Britain’s Black artists. This singular body of work included a series of imposing, oversize portraits of Black people, including archival photographs of the artist’s family members. The scale, posture and composition of the portraits drew heavily on the historical tradition of the sorts of grand portraits of landowners, and other such figures, in the manner perhaps of Gainsborough. Thus Palmer was able, within these fascinating works, to give his Black subject matter a dignity and status that simultaneously resonated with debates about land, landscape, identity, citizenship, and belonging.

It was at this time that Palmer came across the photography of the American Richard Samuel Roberts (1880–1936). Roberts was a contemporary of James VanDerZee, though the two photographers lived and worked in different parts of the US: VanDerZee operated in and around the Harlem district of New York, while Roberts operated in Columbia, South Carolina. Roberts photographed the African-Americans of his community, particularly those who had achieved degrees of affluence and economic stability in their lives. A significant number of Roberts’ portraits were brought together and published in an important document of his work and the times in which he lived.11 Fascinated by some of the book’s portraits of the economically secure, fashionable and self-assured African-American middle class, Palmer used a number of these portraits in his work of the mid 1990s. One such work, based on one of Roberts’ photographs, is reproduced here. Palmer moved on to explore the use of the repeated image in his paintings, particularly those of family members such as his father and his daughters. Commenting on one of these series of portraits, Six of One (1999) Richard Hylton noted that it

was painted in serial form. It is perhaps unavoidable when looking at such works that we inevitably seek out the subtle differences between them, to arrive at some sort of hierarchy of originality. Yet whilst we might revel in the [supposed] accuracy of skin tone in one, the slightly darker [or indeed, lighter] tone of another casts doubt over our previous judgement. Being drawn to one painting over another or, thinking one better over another, becomes, as much of a game as it is an almost fruitless exercise.’12

In considering the paintings of Palmer one can clearly discern over a period of several decades a clear maturing and growth. Palmer’s work was able to combine artistic skill with new and refreshing ways of rendering the Black image, particularly the ways in which the archival image, be that familial or anonymous, intersected with issues of art history and contemporary identity.

Saleem Arif (or Saleem Arif Quadri as he came to be known) is also of that generation of primarily Caribbean and South Asian-born artists who are younger than the pioneering generation of Uzo Egonu, Rasheed Araeen and others, but significantly older than the younger generation of artists that included the likes of Keith Piper and Sutapa Biswas. Born in the Indian city of Hyderabad in 1949, some two years after that country’s independence, Arif came to the UK in his late teens. Within a few years he went to study sculpture at Birmingham College of Art, going on, a couple of years later, to study painting at the Royal College of Art, London. Arif is perhaps best known for producing beautiful, poetic interpretations of natural forms and animal/bird life, rendered in silhouette, in a restrained palette of flat areas of colours. He has been, for periods of time, a prolific artist whose work has been exhibited widely and has found its way into a number of art collections.

Particularly noteworthy in this regard is the 2001 acquisition by the Tate Collection of Arif’s Landscape of Longing (1997–9), a sizeable mixed media work on composite panel. Instantly recognisable as an Arif work, the piece featured wall-mounted sections that have the appearance of something fragmented; something whole being pulled apart, or something fractured being uneasily or tentatively pushed back together. Such works spoke of Arif’s dual training as first a sculptor and then a painter, as Landscape of Longing oscillated between the two dimensional and the three dimensional, in the mind, or to the eyes, of the viewer. As Arif himself recalls, or explains on his website:

Since 1990, all my paintings have been on a versatile wood support, which stands half an inch away from the wall. This device articulates and enhances my new concepts of ‘volumetric’ and of ‘pregnant space’, as the paintings appear to float away from the wall surface, adding a third dimension to my pictorial language.13

For the most part, Landscape of Longing is rendered in a muted shade of white, though each of the shapes is emphasised or embellished by what at first glance resemble incomplete or tentative borders, rendered in quiet or subdued earthy shades of brown. Though somewhat abstracted, the work’s fragmented sections speak of nature, or of natural formations.

In 1983, Arif had a solo exhibition at the Midland Group, Nottingham. The venue was, at the time, (together with Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery) one of the leading Midlands venues for contemporary art. Within the exhibition, Arif explored his interest in Dante’s Inferno, the first part of Dante’s Divine Comedy, written by the Italian Dante Alighieri in the early fourteenth century. Whilst many people have heard of, or might know of, Dante’s Inferno, Arif declared himself as having a pronounced interest in the allegorical work, which tells of the writer’s journey through the inferno, or hell, shown the way by the Roman poet Virgil. In contrast to heaven above, in Dante’s Inferno, hell is represented as nine circles of suffering; hell located below, underneath, or encased inside the earth. Within the epic poem that is the Divine Comedy, the central narrative represents the allegorical journey of man’s soul towards God. According to Rasheed Araeen, Arif’s interest in Dante’s Inferno was not simply academic or disinterested:

It is clear that Arif was preoccupied with the search for a cultural identity. During this time [circa late 1970s/early 1980s] he was also reading Dante’s Inferno and his research uncovered much evidence to support the growing notion that Dante must have known Islamic literature.14

Araeen then goes on to quote from Arif’s exhibition catalogue for his Midland Group exhibition: ‘He [Arif] discovered documents showing that certain passages in the Divine Comedy are virtually direct quotes from Islamic tales. Fired by these inter-connections between east and west, past and present, Saleem was ever more determined to travel.’15 It was perhaps this perceived interplay, or exchange, between East and West that led to Arif being included in the important From Two Worlds exhibition held at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1986.16 In the summer of 2008 Saleem Arif Quadri was honoured in the Queen’s Birthday Honours, receiving an MBE. As such, he was one of a growing number of visual artists of African, Caribbean or South Asian background to be similarly honoured for their endeavours and contributions.17

Chila Kumari Burman, though of the generation of artists discussed thus far in this chapter, differed from them in at least one important respect. Whilst Joseph, Forrester, Palmer and Arif were all born in countries of the Caribbean or South Asia, Burman was born in Liverpool in 1957. She was one of the first of a British-born generation of diaspora artists to complete her art school education, first with a BA from Leeds Polytechnic, then graduating with an MA in printmaking from the Slade in 1982. She took printmaking as her preferred medium, moving from the more traditional forms of the medium, such as etchings, lithographs and screen prints, through to more recent forms which utilise modern technology such as colour photocopying. Her work became distinctive for its consistent embrace of photography and the photographic image, ranging from self-portraiture to found images. Writing in 2001, Solani Fernando touched on Burman’s significance:

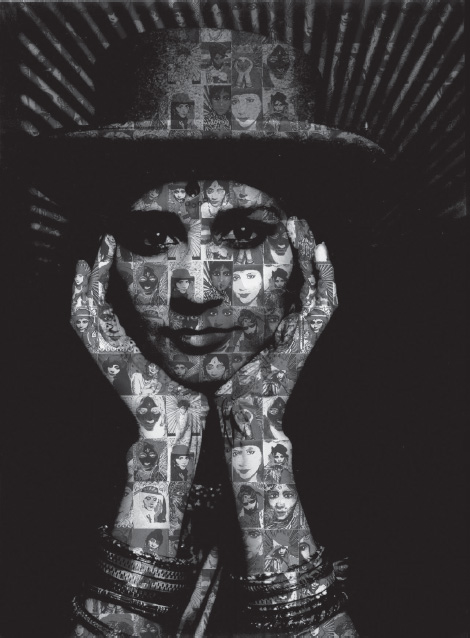

16. Chila Kumari Burman, Auto-Portrait (1995–2014).

Gaining a first class honours degree in printmaking in 1979 and completing her Masters degree at the Slade School of Fine Art in 1982, Burman has been instrumental in opening some of the foremost British art institutions to a politicisation around race and gender. One of the first Black women artists in this country to produce political work.18

Burman’s work was further characterised by an unswerving commitment to a range of social and political narratives. To this end she produced some of the most compelling work that is reflective of the frustrations and the aspirations not only of Burman’s own generation, but also her parents’ generation of immigrants. Typical in this regard was her 1980s print You Allow Us to Come Here On False Promises, in which a range of images, symbols and texts were montaged to form a protest against what the artist regards as punitive institutional discrimination, particularly in the realm of immigration policies and employment practices. The print featured John Bull as Margaret Thatcher (or Margaret Thatcher as John Bull). From Thatcher’s mouth comes a speech bubble with her infamous words of 1978 in which she speaks of a ‘fear’ of the country being ‘swamped’.19 For good measure and effect, Burman included in the screen-printed collage an image of the white South African runner Zola Budd, given British citizenship by Thatcher’s government to enable her to compete for Britain in the then upcoming 1984 Olympics.20 Such a gesture was interpreted by many as a slap in the face for those Black people (many of whom were Commonwealth citizens) denied entry, or harassed at the point of entry, to the UK. Budd’s treatment also implied tacit support for South Africa’s apartheid system.

In the mid 1980s Burman was one of a number of Black artists who undertook several mural commissions in London. One was executed as part of the project to rehabilitate the Roundhouse in North London as a Black arts centre.21 The other was executed in collaboration with Keith Piper as part of the GLC’s Anti-Racist Mural Project. Their mural, painted on boards, was intended to reflect something of Southall’s important history as a site of resistance and struggle. Burman took part in several of the pioneering exhibitions of Black women’s work that were such a distinguished feature of Black visual arts activity in 1980s Britain. A passionate advocate of the rights and demands of Black women artists, Burman was responsible for an important essay that functioned as a manifesto in defence of what she regarded as an often maligned and marginalised group of practitioners. The essay was There Have Always Been Great Black Women Artists.22 Burman’s text reflected many of the sentiments expressed a few years previously in the Combahee River Collective’s, communiqué, ‘A Black Feminist Statement’, in All the Women are White, All the Blacks are Men, but Some of Us are Brave: Black Women’s Studies.23 Burman’s was a bold text that provocatively referenced Linda Nochlin’s seminal essay of the early 1970s, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’24. With respect to issues of absence and discrimination relating to women artists, this was one of the most significant articles ever published; it also addressed matters that would, in time, be referred to as ‘feminist art history’.

It could be asserted that the keystone of Burman’s argument was that the mixed fortunes of Black women artists are not a result of any objective deficiencies in the range of work these artists produced, but rather a result of systemic institutional prejudice and practical obstacles that have hindered these practitioners. Further, Burman’s text prompted considerations of what precisely it was about patriarchal society, a prejudiced art world, and the nature of ‘Black art’, as apparently advanced by some Black male artists, that prevents Black women artists from realising more fully their creative potential. Provocatively, Burman’s text challenged dominant discourses of feminist art history by asking what is it about such texts that prevent a fuller acknowledgement of the question of race and its interplay with sex and gender. A quarter of a century after Burman’s essay was written, it still contains a range of relevant and clear sentiments relating to the multiple practices, challenges and experiences of Black woman artists. Early on in the text, Burman set out her stall:

This paper, then, is saying Black women artists are here, we exist and we exist positively despite the racial, sexual and class oppressions which we suffer. However, we must first point out the way in which these oppressions have operated in a wider context – not just the art world, but also in the struggles for Black and female liberation.25

Burman goes on make mention of the struggles that have

a lot to do with many second generation British Black women reclaiming art; first, as a legitimate area of activity for Black women as a distinct group of people, second, as a way of developing an awareness of ourselves as complete human beings, and third, as a contribution to the Black struggle in general.26

Burman’s text was researched and written at a time of some debate, in certain quarters, about the sorts of sensibilities that Black artists ought to be prioritising within their practices. The notion that Black artists’ work could and should have some sort of active social agency that directly benefited Black people and their struggles was a sentiment that had gained traction in the United States at several points during the twentieth century, and was being somewhat reprised, in a British context, during the 1980s. Burman’s essay gave voice to women who felt that such a position privileged masculine aesthetics and a particularly masculinist approach to art-making and activism. Burman’s work has, latterly, evolved from the two-dimensional into the realm of installation/performance, centring on her innovative use of an ice-cream van to animate aspects of her family history.

This chapter has discussed the earliest Black-British artists, and previous chapters have considered artists whose roots lie in West Africa, the Caribbean and South Asia, but still to be examined are those artists who were born in East Africa.