CHAPTER TWELVE

Black Artists of the 1990s Generation

During the course of the 1990s, other important and original new artistic voices entered the sphere of contemporary British art. The challenges and successes of each of these artists reflected much of the complicated space that so many Black artists came to occupy during the 1990s. Some achieved particular successes in the international arena, undertaking residencies and exhibitions in countries beyond Britain. On occasion, they would avail themselves of residency or exhibition opportunities offered by an important new presence in the London art scene, the Arts Council-sponsored Institute of International Visual Arts – or INIVA, as it became known.1 Sometimes they were able to break free of exhibition contexts that unambiguously signified them by race, ethnicity, skin colour and so on. At other times, some of these artists seem to have been periodically set to one side, in ways that their more successful white counterparts were not.

Amongst these artists were Hurvin Anderson, Godfried Donkor, Mary Evans, Kimathi Donkor, and Barbara Walker. Godfried Donkor was born in Kumasi, Ghana, in the mid 1960s, around the same time that Kimathi Donkor (no relation) was born in Bournemouth, England, Mary Evans was born in Nigeria, and Hurvin Anderson and Barbara Walker were born in Birmingham. Each of these artists made fascinating, compelling work that addressed the dual concerns of excavating or re-excavating history, whilst concurrently opening up understandings and considerations of the contemporary social, political and cultural presence of Black people in Britain, and elsewhere in the world. A sign of the changing times for Black artists could be discerned in the respective profiles of each of these artists. It might be a sign of problems, or it might be a sign of progress, that these six artists kept very little in the way of curatorial company with each other. During the 1980s, the overlap in the varied profiles of Black artists was apparent, as a number of them showed up, time and again, in the same sorts of exhibitions. Not so this 1990s generation of practitioners.

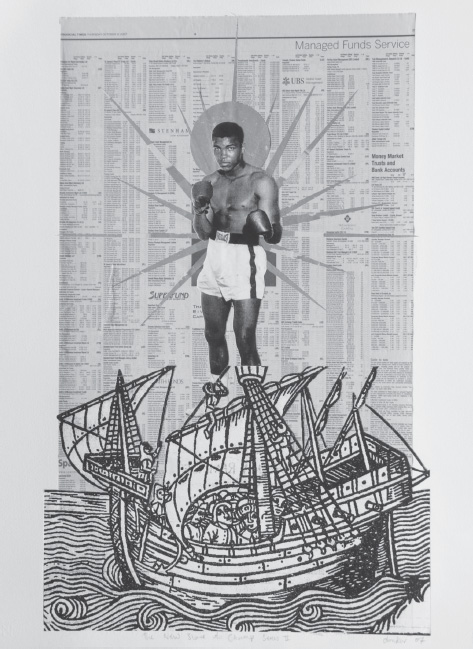

29. Godfried Donkor, Slave to Champ (2007).

One of Godfried Donkor’s most engaging series of work, begun in the mid to late 1990s, was his Slave to Champ paintings. This series featured near-iconic depictions of Black boxers, some from the earliest days of the entry of Black boxers into that particular sport, others from more recent eras of the sport. Donkor’s Slave to Champ paintings and montages often took the form of images of Black boxers apparently standing on, or emerging from, enlarged reproductions of lithographs of slave ships, depicting their human cargo packed below deck like so many sardines in a tin. The origins of these drawings of slave ships and their contents dated back to the abolitionist movements of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The abolitionists had seized on this simple but effective graphic device as a means of driving home the horrors that had to be endured by captured Africans during the middle passage – the nightmarish journey by sea that took captured Africans from their homelands to slavery and death in the ‘New World’. As one historian has noted: ‘Of all the details of the slave trade that appalled anti-slavers, the most immediate – because the easiest to visualise – were those of how the human cargoes were stowed. The arrangements were made widely known in drawings’2

But these powerful lithographs would in time take on a significance that went way beyond their propaganda value of their day. The passage of time did little or nothing to diminish the memory of slavery on the collective and individual psyche of new world Africans and their descendants. Indeed, a century and a half after the abolition of slavery by the British, plans of laden slave ships were starting to become iconic shorthand graphic signifiers for the miserable, wretched history of slavery and the myriad ways in which that history spawned a thousand Black liberation struggles. There were those who might regard slavery as something from the dim and distant past, but Donkor’s work declared that for many Black people the experience of slavery had seared itself on their psyche in a way that few non-Black people could understand. This was one of the most profound ways in which slavery had, for many people of the African diaspora, become a signifier of identity. Donkor’s use of the slave ship motif encapsulated and signified much in the way of Black history. The signifiers of enslavement, exploitation, bondage, torture and death were in any case never far from many Black people’s readings of the slave ship image. Nor, for that matter, were the redemptive signifiers of survival, perseverance and the struggle for humanity.

As one commentator noted, Donkor ‘places his black boxer towering aloft like a giant above a cross section of a slave ship, which recurs as a diagram from painting to painting.’3 That particular commentator, Everlyn Nicodemus, went on to summarise her particular take on these paintings:

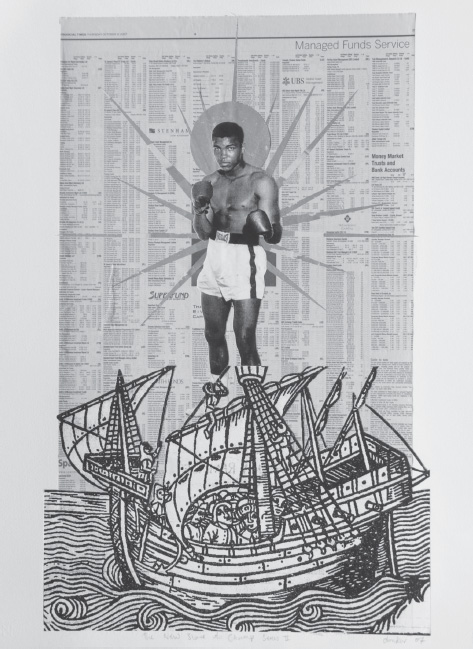

30. Kimathi Donkor, Coldharbour Lane 1985 (2005).

If we look closer at the history of this Black Atlantic track, we find that history supports his choice by confirming a basic fact about how those blacks, who have a background related to slavery, have been allowed to become visible. Their only legitimate field of expression has been as popular entertainers, to whom boxers belong. And the successful way of becoming successful entertainers has been to play the game of the whites, complying with their worst prejudices and skilfully manipulating them them to their own advantage.4

But there was, within Donkor’s portrayals of his boxers, warmth, humanity, and the perseverance of an almost righteous and spiritual struggle for manhood. Consider the incessant demonisation of Mike Tyson, and the ways in which, time and time again, he has been portrayed within the media as being a mindless brute, a thug, and an animal.5 Within Donkor’s depiction of Tyson we see the ‘Champ’, laden with world title belts, but looking anything but menacing.

There is of course much room within readings of these pieces to raise some other critical questions, reflecting or extending the questions asked by Keith Piper’s video, The Nation’s Finest.6 Within this video, Piper, exploring the social construct of the Black British athlete, asked the probing question, ‘stadium or enclosure?’ In other words, does the running track or the boxing ring exist as an environment in which finely honed and well-trained athletes can demonstrate their physical excellence and a range of gladiatorial and non-gladiatorial skills? Or, on a more disturbing and profound level, does the running track or the boxing ring exist as a formidable physical and psychological enclosure? This was Nicodemus’ take on Donkor’s Slave to Champ paintings. Little should perhaps be taken away from Nicodemus’ assertion. After all, the racist notion that Black people were gifted with physical much more than intellectual abilities was apparently an enduring pathology. Notwithstanding Nicodemus’ assertion, one should perhaps be careful in accepting her assertion that Donkor’s work ‘cannot avoid running the risk of confirming certain prejudices, especially the stereotype about the black male as merely a body, strong and potent, the personification of a mindless brute.’7 A more considered look at these Slave to Champ paintings would reveal that Donkor’s work, in subtle and sensitive ways, sought to undermine these stereotypes by accentuating the humanity of the boxers.

Mary Evans was another artist to make particularly engaging use of the slave ship motif. One of the works in question was Wheel of Fortune, produced by the artist in 1996. Within the sobering, imposing, and engaging work, Evans painstakingly cut out of dark-coloured paper, three times, the distinctive shapes – patterning even – of the plan of the slave ship. This was patient, painstaking work that one could imagine involved Evans developing a particularly empathetic relationship with each individual outline of a slave (and of course, the slave ship itself), as she took her time extricating whole fragile, delicate plans of slave ships from the pieces of paper she started with. For the three positive outlines Evans secured for herself, she was left with three corresponding negative pieces of paper. Evans then took these six pieces of paper and alternately placed them on a wall, forming a wheel of fortune, each ship with its bow located within the epicentre of the wheel of fortune, with an equal spacing between the sterns of the six slave ship cutouts. Evans wrote: ‘I wanted to make something decorative out of that particular image. The images at 2 o’clock, 4 o’clock and 10 o’clock are the leftover cuttings from the other images which were cut first. This made positive and negative brown and white figures.’8

31. Mary Evans, Wheel of Fortune (1996).

Within this work, Evans explored the idea of chance and slavery. The historic wheel of fortune, laden with fatal consequences for some, is spun, and x number of Africans are chosen for capture and enslavement, their lives, the lives of their communities, families and indeed, their descendants, forevermore transformed through the horrific experiences of the transatlantic slave trade. The title of Evans’ work, Wheel of Fortune, referenced a long-running American television game show in which contestants competed to solve word puzzles, such as those used in another word game, Hangman, to win money and other prizes supposedly determined by spinning something akin to a giant carnival or funfair wheel. Hardly deviating from its long-running format, Wheel of Fortune was said to be the longest-running syndicated game show in US television history. By titling her piece as she did, Evans introduced a pointed, almost macabre, gallows humour into her commentary on history, fate, and enslavement. The cheery notion of a game show wheel of fortune, complete with its elements of chance, when coupled with an insistent and quite disturbing patterning of the slave ship, acted as a foil for what was a brave and almost audacious piece of work. If the historical shoe had been on the other foot, perhaps it would have been the white people who would have suffered, endured, and had to find ways of surviving the death, destruction and disruption the Atlantic slave trade caused. Whilst certain Africans of all ages and both genders were captured into slavery, the effects of slavery deeply affected much of the African continent, the ramifications and effects of which are still being felt today. Amongst other things, Evans’ work invited its audiences to consider what the world would be like if Africans had systematically enslaved Europeans over a period of several hundred years, rather than the other way around.

Chapter Eight made mention of the riots that took place in London and elsewhere in the country in the early 1980s. Likewise, Chapter Ten referenced the riots that erupted in Brixton and Tottenham as a response to, respectively, the maiming of Mrs Cherry Groce by armed police and the death from a heart attack of Mrs Cynthia Jarrett during the course of a police search of her home. Several artists had made work in response to these riots of the mid 1980s. Some two decades after the events themselves Kimathi Donkor painted scenes that recalled both the death of Mrs Cynthia Jarrett and the riots that took place in Brixton in the aftermath of the maiming of Mrs Cherry Groce, a testament to the enduring significance of the events for Black Britain. In Donkor’s painting that recalled the 1985 Brixton riots, the essential elements were the brutalist and brutalising housing which signified social deprivation, and the attempts to repel the neighbourhood of Brixton’s uniformed invaders.

Along with Railton Road, Coldharbour Lane had over the course of the middle to late twentieth century developed or acquired near-iconic status as one of the original ‘frontlines’, indicating the contested territory where the police and Black youth regularly clashed or otherwise came into confrontational contact with each other. On a map, Coldharbour Lane is one of the main thoroughfares in South London that leads south-westwards from Camberwell into Brixton. Although the road is over a mile long, being a mixture of residential, business and retail properties, the stretch of Coldharbour Lane depicted in Donkor’s painting centres on a few blocks, not too far from Brixton Market and nearby shops, bars and restaurants, where Coldharbour Lane meets Acre Lane in central Brixton. Donkor’s painting recalls a time when Brixton was very much, and very much regarded, as a Black (as in, distinctly African-Caribbean) neighbourhood. True to the ‘frontline’ nature of Coldharbour Lane, Donkor’s painting showed three ghetto defenders, each in various stages of hurling rocks at their tormentors, located outside of the frame of the canvas, some distance to the right of the depicted rock-throwers. In point of fact, we do not know for certain what the first rioter is about to hurl, as his hand and weapon are located beyond the left side of the artist’s canvas. Rock, half-brick, petrol bomb, whatever the weapon, the first rioter, and the one closest to us, is about to let it fly. One of the extraordinary strengths of the painting is its aspect of animation, the ways in which Donkor composes a sequence of steps and movements for each of his ghetto youths. The bodies of each of the three figures are depicted in different stages of movement, creating what is in effect an animation. In this regard, the three figures – despite differences in clothing – become one, carefully choreographed by the artist to provide and create a unity of movement and purpose. Standing as something of a dramatic backdrop to the group of three is an anonymous housing block, its façade of muted colour effectively pock-marked by what seem to be impossibly small windows, making the building more reminiscent of a prison, or a low rent ministry of truth9 than a building made up of homes in which Londoners are expected to live.

Coldharbour Lane 1985 was characteristic of Donkor’s style of painting. He confidently tackled key, dramatic, monumental moments of African diaspora history, but did so with a painterly preciseness that bordered on aesthetic frugality. Despite the animated scene depicted, Coldharbour Lane 1985 resonated with an almost deafening silence, almost as if the riot was taking place with the environmental volume turned right down, or muted altogether. As such, the painting stood in marked and salutary contrast to the shrill, hysterical and sensationalist tones that normally accompanied television reports of urban disturbances, reports that by their nature offered more in the way of heat than light on the causes and anatomies of a riot.

Elsewhere in the country, Birmingham-based artist Barbara Walker was also concerned with documenting the presence of Black Britain. At times, she sought to present a settled community looking to go about its various activities in peace. At other times, she documented a decidedly fractious community, ill at ease with the perceived draconian policing it was forced to endure. Walker did more than simply paint her community, her friends, her family and herself. She was in effect a chronicler, a faithful and friendly documenter of the lives and culture of African-Caribbean people around her in her native Birmingham. Her work was, however, not merely illustrative, or merely social documentation, important though social documentation is. Walker’s work effortlessly exuded a warmth, a familiarity and a humanity seldom within reach of even the most accomplished and empathetic photographer. Walker had grown up in, as well as grown out of, the community that she took as her subject matter. In her early work, like several other Black painters, Walker took as her subject matter the barbershop, itself such an important social focal point in Black communities in Britain, and indeed further afield.

Walker had, over the course of the late twentieth and into the twenty-first century, emerged as one of the most talented, productive and committed artists of her generation. She respectfully painted the experiences, rituals and spaces that bond and characterise so many aspects of African-Caribbean identity. From rituals like those practiced within majority-Black churches, such as baptism by total emersion, through to affirmative and communal spaces used by Black men, such as the barbershop. Her work – painting and drawing – was marked by its profound empathy for its subject matter as much as its distinctive style. There was, within her pictures, great honesty, an honesty that spoke of (as well as to) the human condition in many of its forms. Like the great African-American artist Charles White, Walker’s pictures were ‘images of dignity’ and because her work was highly figurative, audiences had an uncommon access to its multiple and pronounced social narratives.

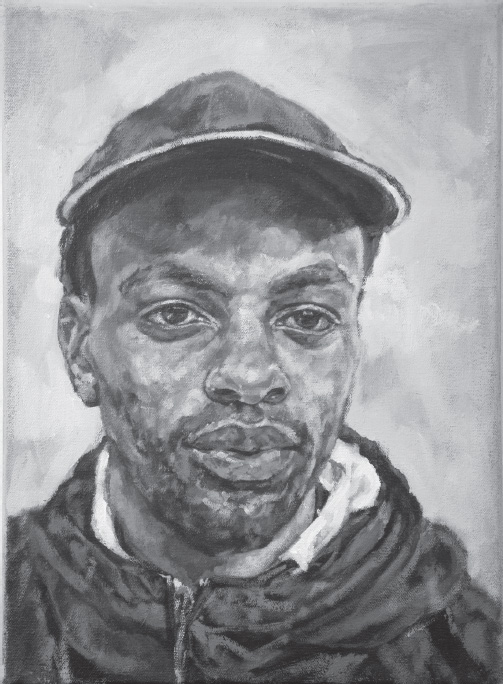

32. Barbara Walker, Solomon (2005).

For one particular exhibition, Walker produced a body of work that unflinchingly and intelligently explored the impact that stop and search has had, and continues to have, on her son, Solomon, as well as on herself as a mother. The exhibition Louder Than Words10 consisted of a series of deeply engaging drawings that directly addressed the personal, social and political implications of the police obsession with stopping and searching those hapless young Black men deemed to be suspicious in appearance or behaviour. As a parent, artist, and life-long resident of Britain’s second city, Birmingham, Walker used her formidable drawing ability to explore the impact of stop and search on her son Solomon who had, on a number of occasions been stopped by the police, questioned and searched.

The resulting work was a series of portraits of her son, or drawn views of her neighbourhood, rendered on enlarged copies of stop and search carbon copies with which he had been issued at the end of each encounter with the police. With this startling and original device, Walker effectively alluded to the sinister and intrusive nature of stop and search, and the ways in which one’s neighbourhood was a menacing and sinister space, rather than a nurturing space of comfort, community and safety. The work also referenced the extent to which certain British people, on account of no more than their skin colour, were subject to constant and unapologetic surveillance. There was a marked and salutary contrast between the juxtaposition of Walker’s precise, confident drawings and the impersonal, bureaucratic compartmentalising of information about human beings reflected by the state’s issuing of these stop and search records, on which these drawings were rendered.

Birmingham had given rise to a number of significant and influential artists of Caribbean background, amongst them Vanley Burke, Keith Piper, Donald Rodney, Barbara Walker and Hurvin Anderson. Anderson is one of the most accomplished painters of his generation, known and respected for the uniqueness of his vision and practice, who emerged into notable prominence during the course of the 1990s. In the years since then he has garnered notable attention in the international arena. Some of his paintings are singular constructions which somehow manage to achieve the – in some respects unlikely – combination of being investigations into colour, shape and form, and unsentimental explorations of cultural and socially charged spaces such as the Black barbershop, and places in Jamaica, the Caribbean island from which his parents had emigrated. Typical in regard to Anderson’s extraordinary investigations into the Black barbershop is Jersey, a painting of 2008 now in the collection of the Tate. Jersey, like other paintings characteristic of Anderson, is a study of the interplay between figurative and non-figurative elements, and the fascinating results that can ensue when the painter’s brushstrokes are used to create what are in effect collages. Jersey (from one of the artist’s celebrated series of paintings) depicts a barbershop, in which two empty barbers’ chairs – perhaps recently vacated of their customers – occupy a decidedly unusual type of environment. The notable presence of abstraction within the painting decisively prevents it from being merely or simply a painterly study of a space of congregation and conversing for Black males, who often found themselves with few other social spaces to gravitate to. The painting is dominated by a wall the colour of light blue, onto which, or in front of which, have been placed rectangles of assorted sizes and colours. With this startling device, Anderson created an astonishingly ambiguous depth of field, rendering the viewer uncertain as to whether the barbershop had a wall or whether it was instead located in a kind of infinitesimal space in which the rectangles of colour floated, as if in some sort of neverending void.

33. Hurvin Anderson, Peter’s Sitters II (2009).

Like several artists before him, it was in some regards the space of the Black barbershop that Anderson sought to commemorate or illustrate in paintings such as Jersey. In so doing, Anderson produced a remarkable and wondrous body of work. Jersey embodied a certain luminous and optimistic disposition, with its combination of a bright, light pastel blue, and the rectangular shapes of lilac and other colours that resembled small patches of colour painted or affixed to a wall rather like those homemakers might live with before they decide on a final colour scheme for this or that room in their home. In this regard, with its partial emphasis on decorative elements, Jersey effectively displaced or troubled dominant societal notions of African-Caribbean males. In referencing elements of the modernist grid, colour field painting, and Black male grooming, Anderson was producing singular work of pronounced sophistication, capable of telling no end of stories. There was an insistent oscillation between abstraction and figuration in Anderson’s work, consequently imbuing it with a wealth of painterly, visual art, as well as cultural and historical narratives.

Faisal Abdu’Allah was born in London in 1969, and graduated from the Royal College of Art in the early 1990s. A number of the artists discussed in previous chapters and the current one – Bowling, Forrester, Arif, Piper, Anderson – had all studied at this important London graduate art college. A measure of the Royal College of Art’s significance in narratives reflecting the presence of Black artists in Britain was indicated in the exhibition, RCA Black, which took place at the Royal College of Art, Henry Moore Galleries, London, 31 August – 6 September 2011. The exhibition celebrated the work of a number of Black artists who, over the course of the last half a century, had been able to study at the institution.

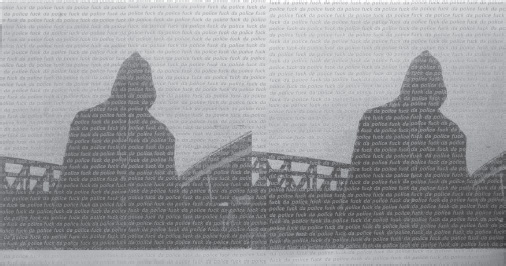

34. Faisal Abdu’Allah, Fuck da Police, (1991).

Abdu’Allah’s work was emphatically reflective of the cultural and political influences that have shaped a generation of Black British people for whom Black urban American street style, language, aesthetics and music were profound and critical influences as they came of age. In looking at Abdu’Allah’s work, Black Atlantic and other diasporic sensibilities were consistently discernible.

His first exhibition, titled Censored! From Nigger to Nubian, took place at the 198 Gallery, in South London, in 1993.11 It consisted of a series of works – screen prints on etched steel – that were, for a while, to become something of his trademark. One particularly imposing series consisted of five full-length portraits of young Black men, printed on oversize sheets of steel. The work was at once gritty and contemporary, and, despite the unquestionable power and strength of the portraits, was simultaneously enigmatic and understated. In this regard, steel was a singularly original and appropriate medium on which to screen-print the images. Steel is a material that in its making is quite literally forged in the fire, and yet upon manufacture can acquire a cool, minimal, and decidedly modernist aesthetic. The images of the young Black men all provocatively engaged with, or oscillated between, rap iconography and the objectification of young Black males as having a close proximity to criminality, deviance, and threat. Within this work, the artist appropriated iconography from popular culture in an attempt to question particular pathologies – both spoken and unspoken – relating to media and other representations of the young Black male.

A particularly photogenic and media-savvy personality, Abdu’Allah carved out for himself a substantial place in the landscape of visual arts practice in twenty-first century London. The intellectual depth, integrity, and consistent originality of his work marked him out as a hugely important and relevant artist. The role of Black people in society, in history, in art, and in numerous other spheres, is of central importance to Abdu’Allah. Another of his much-celebrated works (Last Supper, 2003) is a sizeable reworking of the symbolism of the image of the Last Supper. In Abdu’Allah’s reworking, commissioned by Autograph, the by now long-running Black photographers’ agency, the figures have been made over to reflect the artist’s own identity as a Muslim, as well as his critique of the ways in which Black people – both men and women – have been largely excised from mainstream (including biblical) narratives. Like much of his work, his rendering of the Last Supper (in two different versions) boldly challenged the viewer, as well as presenting its audiences with masterfully executed, intriguing, grand visual narrative.

Another artist to decisively make a name for himself during the course of the 1990s and on into the new millennium was Hew Locke, who was born in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1959 but lived from 1966 until 1980 in Georgetown, the capital of Guyana, the country of his father’s birth.12 He gained a BA in Fine Art from Falmouth School of Art (having studied alongside another significant young practitioner, Alistair Raphael) and an MA in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art, London, in 1988 and 1994 respectively. Locke’s distinctive work was widely celebrated for what sometimes appeared at first glance to be offbeat and slightly eccentric sculptural forms. Frequently, during the early years of the twenty-first century, these sculptural forms were renditions of prominent members of the British royal family. Closer inspection of his work revealed, for some, much more intellectually textured and heavily nuanced readings.

Locke achieved considerable success and recognition by the middle of the 2000s and his work was exhibited in substantial group and solo exhibitions in the UK and internationally. Locke is one of only a limited number of Black British artists to have their work included in the British Art Show13 – in Locke’s case, in the sixth manifestation of the exhibition, which toured to venues in Gateshead, Manchester, Nottingham and Bristol in 2006. He had a major solo exhibition at the New Art Gallery Walsall in 2005.14 The lavish and sizeable publication that accompanied the exhibition included a substantial and useful essay on Locke’s work, ‘King Creole – Hew Locke’s New Visions of Empire’ written by Kris Kuramitsu.15 The publication also contained ‘A Sargasso Sea-Hoard of Deciduous Things… Hew Locke and Sarat Maharaj in conversation’, in which Maharaj shed much calm, reflective and perceptive light on the nature and complexity of Locke’s practice. The conversation opened with Maharaj reflecting:

35. Donald Locke, Trophies of Empire (1972–1974).

For me the singularity of your work springs from its wit – its humour and sense of play. These qualities are at odds with the earnest tonals and high seriousness of concepts like ‘postcolonial, trans-national, commonwealth, creole’ – even if they do throw keen light on your ways of seeing and making. The wit seems to resist and short circuit blanket categories that claim to ‘explain’ the shape of your thinking and practice.16

Indeed, these sentiments could, perhaps, be applied to many of the artists who stamped their imaginative and thought-provoking impressions on the 1990s.