EPILOGUE

The New Generation

As mentioned in the Introduction, every chapter of this book could have been titled Problems and Progress, because either an entrenching of ongoing challenges, or the creation of new ones, has invariably accompanied each step that Black artists have taken towards greater visibility. The history of Black artists in Britain reflects a steady and often predictable pattern, in which the fortunes of individual artists undulate, whilst the majority of practitioners have to settle for either fleeting visibility, or no visibility at all. Each of the decades studied in this book has produced remarkable artists whose practice is both in step with the times and simultaneously something unique, something different, something fresh. But Britain has yet to learn to keep hold of its most gifted Black artists. Time and again, the country has seen its most successful Black artists either reach for more appreciative environs, or turn their backs on a country which had long since turned its back on them. At times, the individuality of the practitioners seemed to count for very little. Instead, the British art scene seemed capable of dealing with Black artists only en masse, as it were, such as in the group exhibitions that proliferated in the 1980s and beyond. As time went on, and the face of cultural politics changed, Black artists in Britain increasingly found that their most substantial opportunities took the form of initiatives linked to festivals, or other projects that had community engagement or notions of racial/social uplift at their core.

In some ways, the Arts Council-sponsored Institute of International Visual Arts was an intriguing new presence in London from the early 1990s onwards, but INIVA’s relationship to the country’s Black artists has always been a decidedly unstraightforward affair. Furthermore, a gallery space (as currently exists) supposedly dedicated to engaging with a plurality of practitioners has implications that are spectacularly troubling.

Nevertheless, a new generation of Black artists is functioning in London, and doubtless new practitioners will continue to emerge over time. Among the new artists to emerge in the twenty-first century can be listed the likes of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Grace Ndiritu, Samson Kambalu and Zenib Sedira. In April of 2013, when the shortlist for the 2013 Turner Prize was announced, the inclusion of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s name was perhaps not a particular surprise. Not only had she been making waves in the UK, with significant attention from the art press,1 but she had also been the subject of an important exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem, a leading New York gallery that had also shown a number of other Black British artists such as Yinka Shonibare, Hurvin Anderson, and Chris Ofili.2

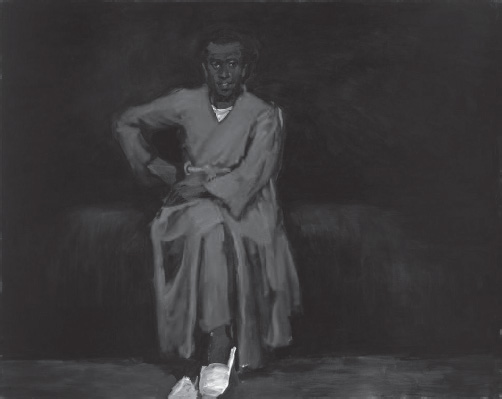

Yiadom-Boakye distinguished herself by producing the most enigmatic of portraits. She tended to take as her subjects Black people not drawn from life but instead taken – assembled, almost – from a variety of secondary material. The significance of the successes achieved thus far by Yiadom-Boakye cannot easily be overstated. It appears that, like Steve McQueen before her, she has found ways to present a largely non-racial reading of the Black image. As mentioned in the previous chapter, in a world in which the white image stood for the general and the Black image stood for the racially or ethnically or culturally specific, McQueen’s work seemed to challenge this debilitating and constraining pathology. Likewise, Yiadom-Boakye seems able to use or construct the Black image in ways that, whilst not exactly transcending race or difference, are able to wrestle it free from the limited range of readings that historically seemed to plague the Black image. And like McQueen, Yiadom-Boakye seems able to break what had been, for so many practitioners, a somewhat debilitating coupling of the words Black and artist, even though her portraits reflect an unblinking examination of Black portraiture.

The men and women presented in Yiadom-Boakye’s portraits are often decidedly dark-skinned and as such represent an almost over-determination of Blackness. In some portraits this is achieved by the visibility of the whites of the subjects’ eyes. In others, this sense of over-determination is achieved by the showing of the subjects’ teeth. There is also the use of the decidedly dark backgrounds or overall environments in which the artist locates her subjects. For a Black artist to be able to paint Black people and to draw positive attention from the art world is rare indeed.

Grace Ndiritu is another young artist who came to attention in the first decade of the twenty-first century as a result of her striking practice. Of Kenyan parentage, Ndiritu is celebrated for work that came to be referred to as Handcrafted videos or Video Paintings. At a time when a number of artists were known and celebrated for the use of textiles within their work, Ndiritu distinguished herself by her remarkable use of textiles in the video works she creates. Typical in this regard is her video, The Nightingale (2003). In a perhaps deceptively simple film, Ndiritu continuously wraps and unwraps her head and face with a piece of fabric. But this is not simply a now-you-see-me-now-you-don’t video self-portrait. Not only is the fabric used highly nuanced, evocative of Islamic patterning, but the almost bewildering variety of ways in which Ndiritu reveals and/or conceals herself each carries pronounced associations in the mind of the viewer. One moment the cloth is wrapped in the manner of a hastily applied death shroud, in the next Ndiritu wraps her face as if mimicking the headgear of rock-throwing young Palestinians of the Intifada, at pains to mask their faces to prevent subsequent identification. One moment, the cloth signifies the covering of a woman’s hair or face to preserve modesty, at other times, Ndiritu wraps herself as if mimicking the do-rag, with all its pronounced references to strands of hip hop and African-American culture. At times, the fabric appears as a shawl, evoking piety, at other times, it appears as if Ndiritu’s removing herself from view assumes altogether more different associations of one having been silenced, or one whose visibility had been questioned or compromised. This was astonishing work, which was duly noted as such. Running to just over seven minutes,

36. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Any Number of Preoccupations (2010).

The Nightingale is a powerful video concerned with projected identity and miscommunication. Originally based on a story of unrequited love – the title making reference to the bird famous for its beautiful, sad song – it has become more fixated on the disconnection between the East and West, global separation and cultural stereotyping.3

A number of artists discussed in this book relocated to other countries; but this migration was, however, very much a two-way process, and a number of artists from other parts of the world continued to move to London, pretty much as they had done for many decades. One such was Zenib Sedira, who moved to London from Paris in the mid 1980s. Very much a multimedia artist, Sedira’s early work was marked by its investigations into issues of language and storytelling, and familial relations, within the context of her family’s experience of immigrating to France from Algeria, Sedira’s subsequent growing up in Paris and, subsequent to that, her move to the UK in the mid 1980s. With France’s fractious relation to one of its biggest (ex)-colonies, and the protracted and bloody war for independence as such potent aspects of her family background, Sedira’s work struck a variety of chords in the ways in which it mined history and identity. Black artists in Britain, of the 1980s in particular, were used to dealing with issues of migration and colonial legacies in their practices. Sedira, however, has brought renewed depth and relevance to her explorations of these issues. Two decades earlier, another London-based artist, of Algeria background, Houria Niati, had also investigated France’s colonial legacy in Algeria, though for her the paintings of Delacroix and the medium of paint were her preferred tools in this endeavour.

During the first decade of the twenty-first century, a significant number of new Black artists appeared on the art scene. These included Oladélé Ajiboyé Bamgboyé, born in Nigeria in 1963, who developed his interest in photography during and after his time as a student in Glasgow in the 1980s; Harold Offeh, born in Accra, Ghana who, like a number of other artists of his generation, worked in a range of media including street performance, video, and photography and sought to reference popular culture and to use humour and parody to engage and confront the viewer with a range of social and cultural concerns; Haroon Mirza, born in London in 1977, whose fascinating, intriguing work combined household objects and repurposed electrical appliances to create decidedly odd, but deeply engrossing work that was both sculptural and aural; Tariq Alvi, born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, who achieved considerable success with his innovative mixed media explorations of sexuality, territory, identity, and culture; and Janette Parris, an artist concerned more with making interventions than with making objects. Decidedly eclectic in its manifestations, Parris’s work embraced video, animation, cartoons, musical opera and performance.

While in the case of artists such as these it might be too early to assess the full extent of their position within British art, there are a number of practitioners who have managed, one way or another, to be represented in certain narratives of British art. The most pronounced manifestation of this occurred in the 2012 Tate Britain exhibition, Migrations: Journeys into British Art, an important exhibition that included the work of some 70 artists.4 The exhibition proposed the view that for the past five centuries or so, Britain itself has been shaped by successive waves of migration, from Europe, from the Caribbean, from Asia, and other parts of the world. Furthermore, that what we know as, or consider to be, British art has itself been similarly shaped. The exhibition advanced, or prompted, the question: what is British art? It proposed that genres audiences think of as most typically British, such as landscape painting, were in actuality introduced by artists who had migrated to Britain. Foreign-born artists frequently secured lucrative commissions and many became, in effect, not just British artists, but Britain’s artists. A combination of European painters steeped in an academic tradition and British artists who travelled to study in Italy helped to introduce a neoclassical vocabulary into British painting. Much later, from the mid nineteenth century onwards, a transatlantic dialogue developed between British artists and American artists such as James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent. Throughout history, Paris too existed as a magnet for artists, and French artists such as Henri Fantin-Latour and Alphonse Legros were regular visitors to England.

Fittingly, artists from the first-ever diaspora – the Jewish Diaspora – featured prominently in the Migrations exhibition, and a significant number of early twentieth century artists, including David Bomberg, Jacob Epstein and Mark Gertler figured in the history of British art. These influential practitioners were joined by a number of established artists including Naum Gabo, Oskar Kokoschka, Piet Mondrian and Kurt Schwitters. This latter group were amongst the refugees from the rise of Nazism and Fascism in Europe in the 1930s. Within just a few years of this (indeed, even before this wave of refugee artists), as discussed earlier in this book, artists were making their way to Britain from countries of the former British Empire such as Guyana, India, Pakistan and Jamaica. Such artists included Ronald Moody, Frank Bowling, Rasheed Araeen and Aubrey Williams.

The story of successive periods of migration influencing British art continued in the 1970s with the decidedly international rise of conceptual art involving an intriguing group of artists such as David Medalla, David Lamelas and Gustav Metzger. These artists were both international in their approach to their own practice as well their approach to their own identities. Towards the final, and most recent chapters of the Migrations story, the politically and socially charged climate of the 1980s gave birth to a compelling and dynamic range of visual art aligned to social commentary, in the work of Black Audio Film Collective, Keith Piper, Sonia Boyce, and Donald Rodney. The work of these artists effectively explored the duality and the nuances of being both ‘Black’ and ‘British’.

The final sections of Migrations reflected the present-day nature of London and other parts of the UK as an international destination of choice for artists from across the globe; the other side of a process that has seen British artists seek to establish themselves in other parts of the world. This dual process has created a fascinating cultural space characterised by a constant process of reinvention and change. Artists such as Peter Doig, Steve McQueen, Wolfgang Tillmans and Tris Vonna Michell networked globally with a speed and effectiveness enabled by plentiful travel opportunities and advances in technological communications. Although not the first project of its kind, Migrations told a compelling story of the vital part migration, and the migration of artists, has played in the shaping of what we know as British art and culture.