CHAPTER 2

HOW WE ARE LOSING FAMILY CAPITAL

W ith the understanding that family capital contributes to business success and fuels national economic growth, let’s examine those societal trends influencing and oftentimes undermining the development of family capital today: marriage rates, fertility rates, divorce rates, cohabitation rates, and out-of-wedlock birth rates. In this chapter I will describe the impact of these five factors on family capital and then present data from the four major racial groups in the United States—whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans—as to how they fare along these five factors. These data will help answer the self-employment puzzle described in chapter 1. Later on, I will examine how certain countries worldwide are faring with these trends.

Marriage provides several direct sources of family capital, the most obvious being human capital. When starting a business, spouses frequently provide labor and at times important expertise (often unpaid) to help a new business grow.1 Social connections or financial resources that a spouse brings to a marriage can also prove crucial in starting a new enterprise or solving a variety of problems. Data from several sources indicate firms founded by married entrepreneurs are likely to have more staying power than those founded by entrepreneurs who are not married.2 This is likely because entrepreneurs are more willing to take risks and can remain in business longer if their spouses also have incomes and can provide health insurance. The employed spouse provides not only a financial safety net but also a “psychological safety net” of encouragement and support during difficult times. Psychological support is important even if one is not starting a business. An early study of Asian and Latino immigrants to the United States found that “being married and living with the spouse increases the odds of self-employment for each ethnic group.”3 For men and women, being married increases the chance of self-employment by 20 percent.4 I sometimes tell my students, “If you really want to be a successful entrepreneur, get married first!”

Entrepreneurs definitely have challenges managing work-family relationships, but many of my consulting clients have been successful both in marriage and business. A study I conducted several years ago noted that over 80 percent of entrepreneurs surveyed were “quite satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their marriages.5 A successful entrepreneur I know well, Steve Gibson, sold his oxygen business and then partnered with his wife Bette in a new social venture. They now work with poor young people in the Philippines and Mexico, training them to start new enterprises since traditional employment isn’t generally available. Steve has always said that Bette’s support was important to him in launching a successful entrepreneurial career, and they are now partners in their social venture.

Recent demographic trends in the United States, however, point to a decline in marriage rates and thus the advantages that can accompany marriage. In the United States the average age at first marriage in 1970 was 22.5 years old for men and 20.5 for women; in 2017 it was 29.5 (men) and 27.4 (women).6 In terms of percentages, in 1960 about 70 percent of Americans over the age of fifteen were married; by 1990, the numbers had fallen to 61 percent and by 2017 the percentage was 54 percent.7 Today fewer Americans access family capital through marriage than ever before. A few years ago I heard one woman in her forties complain: “I just saw the statistics. It’s more likely that I’ll be killed by a terrorist than find a man to marry!” Her overdramatization notwithstanding, clearly, in the United States young people are delaying marriage until their mid to late twenties. One study reported that one in seven adult Americans has decided to forgo marriage completely.8

Compared with today, birth rates in previous generations were relatively high, as children were seen as economic assets to help on the farm or in the father’s line of work. Not all children lived to maturity, and having many children provided a hedge against the potential loss of a child due to illness, injury, or death. In the case of my own family, my grandmother Ada Dyer had seven children who all lived to maturity, and her mother Sarah Gibb had thirteen children, four of which died in infancy. But due to the recent trend of smaller families, one study noted that this decline in family size hinders entrepreneurial activity: “Individuals from smaller-sized families may perceive that they have inadequate potential resources available from kin members, and thus decide against starting their own firm.”9

Another study reported that 25 percent of the firms in their sample employed family members at the time of start-up.10 Moreover, “the larger . . . [the] family units, the larger the pool of people from whom small entrepreneurs might borrow.”11 One example of this is the Amish community, where couples with ten children are not uncommon. Thus, an Amish person could have 90 first cousins (180 if you count the spouse’s first cousins), “each of whom is available as a potential lender.”12 Finally, another study reported that although family members may not loan money they could help make connections with people and institutions that have money to lend.13

My own family history provides a rather extreme example: my great-grandfather, John Lye Gibb, was born in England in 1848 and married Sarah Silcox, with whom he had thirteen children. They emigrated to the United States where, led by religious beliefs, Sarah and John asked Hannah Simmons to become John’s second wife in a polygamous marriage. This new wife added ten more children to the Gibb family, for a total of twenty-three. After being imprisoned for six months for polygamy, John Lye Gibb moved his family to southern Alberta, Canada, where bigamy laws were not enforced. There he became a prominent businessman, as his ten sons who lived to maturity helped him run the “John Lye Gibb and Sons” shoe and harness company. Thus polygamy, deemed barbaric by some, provided important human capital for my great-grandfather.

Association with entrepreneurial family members and working in the family business are two of the best predictors of future start-up activity and subsequent success; family size increases the opportunity for such experiences. Besides the increased likelihood of starting a business, a child (or other relative) working in the family business prior to starting her own will find that experience to have a positive impact on the business she starts.14

But finding family members to work with may prove more difficult in the future. Total fertility rates have plummeted in the United States in recent years, from 3.65 in 1960 to 2.48 in 1970 to 1.84 in 1980; 2017 saw the lowest birth rate in US history—1.77 children per woman, solidly below replacement rate.15

I am aware of cases in which a husband and wife working together in a business get a divorce but are able to still work amicably together—and apparently still share the various forms of family capital. However, all too often divorce significantly damages family capital. Research has stressed the importance of transferring social capital to your children in order to help them succeed.16 Since divorce often disrupts ties between parents and children, that becomes more difficult. Divorce also makes it more difficult for families to work together. Fairlie and Robb report that “having only one parent at home limits potential exposure to family business, particularly if the absent parent is the father”17 Divorce can also undermine trust between parents and children, since children generally grow up believing their parents will always be together. Violated expectations lead to distrust. Paul Amato, a highly regarded sociology professor at Penn State University, in reviewing the literature on divorce, notes that “children in divorced families tend to have weaker emotional bonds with mothers and fathers than do their peers in two-parent families.”18 If emotional distance or distrust become part of the family dynamics, likely fewer family members would work in a business together, and if they did, conflicts would probably spill over into the business. Poorer firm performance and fewer family firms transferring to the next generation would result, since the founders’ children would have had little or no association with the business.

Divorce also can have a negative impact on the family human capital inasmuch as it affects a family member’s ability to function effectively and be a significant contributor to the family. Professor Amato explains some of the risk factors associated with divorce: “Children with divorced parents continued to have lower average levels of cognitive, social, and emotional well-being, even in a decade in which divorce had become more common and widely accepted.”19 Moreover, divorce has also been correlated with increased drug use by the children of divorced parents.20 Whereas substance abuse has many causes other than family disruption, it has a devastating impact on family capital, draining families financially, physically, emotionally, and even spiritually. In 2017, over seventy thousand people died in the United States from a drug overdose, which is about fifteen thousand more than the number of American servicemen and women who died during the entire Vietnam War.21 Thus, drug addiction touches virtually everyone in American today and most homes throughout the world. To avoid this scourge, families need to provide a stable and nurturing environment for children to flourish, and also provide needed support when family members struggle. Stable families create stronger people who can turn to their families for support rather than turn to drugs or alcohol to cope with their problems.

Furthermore, several studies indicate that the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral problems of children of divorced parents often don’t improve if the parents remarry and the child becomes a member of a blended family.22 And family financial capital is also undermined through a divorce since family assets are divided between spouses and cannot be pooled to start a business or support family members. Divorce often triggers economic hardship in the family.

One day, early in my career, I received a phone call from an entrepreneur who heard that I was a family business consultant. He wanted to have lunch with me to ask a few questions about his family business. I’m always up for a free meal, so we met at a local hotel the next week for what I thought would be a short lunch. After a few minutes seated at the table, the man said, “I guess you’re wondering why I asked you to lunch. Well, I’ve had a problem with my family business: I fired my son a couple of weeks ago because I felt he was doing something unethical in the business. My wife is so mad that she’s kicked me out of the house and I’m sleeping on a couch at my office. Can you help me?” As you might suspect, his problem is not a typical one that I encounter. I encouraged the man to get some professional marriage counseling, but I also felt I could help him improve how he worked with family members in his business. After a few weeks I helped him rehire his son and he was back sleeping in his own bed. However, the family relationships remained very volatile as I consulted with this entrepreneur and his family over the next several years. Eventually, as the marriage broke down, the couple got a divorce. When dividing up the assets of the business, they realized the business had to be sold. It was, the family fractured, and my lunch companion died alone several years later, in a place far from home and the location of the former family business. The divorce undermined much of the family capital that the family had built up over the years.

The United States is experiencing an era of historically high divorce rates. The number of divorces per 1,000 married women in 1960 was 9.2. The divorce rate rose sharply to 14.9 per 1,000 in 1970 and peaked at 22.6 in 1980; it showed a slight decline in 1990 to 20.9 and has leveled out at 16.4 in 2009 (which translates into about 45 percent of first marriages ending in divorce).23 The stabilization of the divorce rate in the United States is likely due to the following:

» Tougher economic conditions that make staying together a better financial option.

» Cohabitation among those likely to be poorer marriage partners, so that divorce becomes unnecessary when the couple splits.

Cohabitation, or living together in an emotionally and/or sexually intimate relationship, is most often viewed as a stepping-stone toward marriage rather than as an alternative to it. However, research indicates that cohabitation fails to provide couples with many marriage benefits, including family capital. When compared in the aggregate to married couples, cohabiters have poorer physical and mental health,24 less happiness,25 a lower-quality relationship with their partners,26 decreased productivity at work,27 and shorter longevity.28 Research particularly pertinent to family capital indicates that couples in a cohabiting relationship have poorer relationships with their parents29 and are not as connected to the larger community (such as in-laws and churches) as are married individuals.30 Cohabiters are also less likely to pool their resources and work together to meet financial or career goals.31 In essence, they act more as individuals than as a couple. Another study also found that children of cohabiting parents had more behavioral and emotional problems and lower school attainment than did children of married parents.32 Also, if the cohabiting male is not the biological father to the children, there is a much greater likelihood of sexual or physical abuse.33 If a child’s emotional health is compromised, he or she may be less able to contribute to family capital in the future.

Cohabitation rates have dramatically increased during the last several decades. The number of cohabitating couples in the United States increased thirty-five-fold between 1960 and 2010.34 Additionally, serial cohabitation (cohabitating with several different people over time) increased by over 40 percent over the past twenty years.35 Recent US data show that 14.7 percent of females and 13.3 percent of males cohabited between 2011 and 2015, a 63 percent increase for the women and a 33 percent increase for the men since 2002.36

Cohabitation can sound like a good idea to individuals exploring a long-term relationship, but it can actually undermine relationship stability. Cohabiters marry about 50 percent of the time, but when they do marry, most studies indicate they are much more likely to divorce than those who did not live together before they were married.37 As compared to married couples, cohabiters break up more frequently (married couples stay together 2.5 times longer than cohabiting couples), and 80 percent of the children of cohabiting couples will spend some of their lifetime living in a single parent home.38 Moreover, about half of the children who have experienced divorce in their own families cohabit before they marry (between 54 percent and 62 percent) while only 29 percent of children with parents who stayed married decided to cohabit before marriage.39 That is probably because children of divorce may hesitate to marry given their negative experience and thus see cohabitation as a reasonable alternative.

The Fragile Families Study based at Princeton University summarizes the risk factors associated with children born to unwed parents: they are less healthy on average at birth, often grow up in poverty, experience more anxiety and depression, have more behavioral problems, and do poorly in school, as compared to their peers with two married parents.40 Although exceptions clearly exist—my maternal grandmother raised four healthy children after her husband died of appendicitis in his early thirties, for example—in general, children raised with only one parent tend to have a more disrupted home life. Furthermore, because their family capital is typically limited to the resources of one parent, they have fewer familial resources to draw upon (as compared to two-parent families). My mother told me many stories about the challenges growing up in the Great Depression with the family’s only income coming from her mother, a first-grade school teacher. Her family never owned a home growing up—they rented a small apartment attached to the landlord’s home—and my grandmother often had to rely on credit from the local grocer to keep her family fed. As a ten-year-old child, my mother was sent by her mother to the local grocery store to pick up some groceries, only to be denied the food because her mother was delinquent on her account. While my grandmother did the best she could, it was difficult to provide for four young children during the Great Depression.

The percentage of out-of-wedlock births in the United States has skyrocketed in the last several decades, from 5 percent of all births in the 1960s to 41 percent in 2009.41 (Non-marital births, while remaining at historically high levels, have declined slightly in recent years.42) Much of the increase in out-of-wedlock births is due to its social acceptance in the United States. One survey noted that 78 percent of women and 70 percent of men in the US strongly agreed with the statement: “It is okay for an unmarried female to have a child.”43 But a recent study using the NLSY97 dataset notes that having a child out of wedlock increases the risk of consistently poorer economic outcomes for the children, their mothers, and their unwed fathers and is an underlying factor in income inequality in the United States.44 These data are another indication of the important role of intact and stable families in economic development.

Historically, marriage was deemed to be a primary goal for both men and women; for women it provided economic security and for men potential heirs. Moreover, marriage was valued since it generally enhanced one’s social standing. Children were seen as assets by their parents because they provided labor and economic and social support for the family. Children were the designated resource to care for their parents as they aged. Furthermore, marriage and having children was encouraged by religious leaders. Clerics from the Christian tradition encouraged their parishioners to marry and “multiply and replenish the earth” as commanded by God in the Bible. Under these cultural conditions and practices, marriage and birth rates were high compared to such today.

Why have marriage and birth rates fallen so precipitously over the past several decades? The answer can be found in the attitudes and beliefs of many young people today regarding marriage and children. Many young people have witnessed the pain of the divorce of their parents, family members, or friends and have seen the economic and social challenges of marriages. In contrast, I grew up in a neighborhood where divorce was virtually unheard of, and we all assumed (probably incorrectly) that most people were happily married. So, through childhood and into early adulthood, I viewed marriage positively. Today, such a view is rare. And concerning children, I can paraphrase one of my single business students who said, “Children are a lot of hard work and they cost a lot to raise. In doing a cost-benefit analysis of having children, for many of us, the costs outweigh the benefits.” (One recent survey from the United States shows that the cost of raising a child born in 2015 was $233,610.45)

Where do these current beliefs about marriage and family come from? Many cultural icons of today—movie stars, politicians, writers, social activists, business leaders, and others whom young people today look to for guidance—tend to discount the importance of marriage and having children. For example, Oprah Winfrey has said that she didn’t see marriage or children as part of her future. In one interview she said, “If I had kids, my kids would hate me. They would have ended up on the equivalent of the Oprah show talking about me” (Hollywood Reporter interview, 2013).46 Other influential people have expressed similar views. Some of the following statements were intended to be humorous, but I believe they do reflect many people’s views about family:

» “Marriage is the most expensive way for the average man to get laundry done” (actor Burt Reynolds, as reported in the Huffington Post).

» “We’d probably be excellent parents. But it’s a human being and unless you think you have excellent skills and have a drive or yearning in you to do that, the amount of work that that is and responsibility—I wouldn’t want to screw them up” (actress and talk show host Ellen DeGeneres in a People essay).

» “I don’t like [the pressure] that people put on me, on women—that you’ve failed yourself as a female because you haven’t procreated. I don’t think it’s fair. You may not have a child come out of your vagina, but that doesn’t mean you aren’t mothering—dogs, friends, friend’s children” (actress Jennifer Aniston in an Allure interview).

» “Getting married is a lot like getting into a tub of hot water. After you get used to it, it ain’t so hot” (Minnie Pearl of the Grand Ole Opry as reported by the Huffington Post).

» “I’m an old fashioned romantic. I believe in love and marriage—but not necessarily with the same person” (actor John Travolta as reported in the Huffington Post).

» “I work too much to be an appropriate parent. I feel like a bad mom to my dog some days because I’m just not here enough” (TV personality Rachael Ray in People).

» “It’s like, ‘Do you want to be an artist and a writer, or a wife and a lover?’ With kids, your focus changes. I don’t want to go to PTA meetings” (singer Stevie Nicks to InStyle).

» “Someone once asked me why women don’t gamble as much as men do and I gave the commonsensical reply that we don’t have as much money. That was a true but incomplete answer. In fact, women’s total instinct for gambling is satisfied by marriage” (social activist Gloria Steinem as reported by the Huffington Post).

» “My wife and I were happy for twenty years. Then we met” (comedian Rodney Dangerfield as reported in the Huffington Post).

» “I don’t have the marriage chip, and neither of us have the greatest examples of marriages in our families. Jen is the love of my life, and we’ve already been together four times longer than my parents were married” (actor and Mad Men star Jon Hamm in Parade Magazine, speaking about his break-up with Jennifer Westfeldt, his girlfriend of eighteen years).

These statements reflect a growing disillusionment with the institution of marriage and the role of a mother or father. The narrative around this disillusionment is found in the following set of beliefs:

» I don’t think I would be a good wife/husband or mother/father, so marriage and parenthood are not for me.

» Marriage is risky since many marriages fail; furthermore, marriage can inflict pain and can be expensive both psychologically and financially.

» Raising children is time consuming, costly, and boring.

» Having a career is more important than marriage and children. Raising children is not as valued in society as your career outside the home.

» Cohabiting and relationships outside of marriage can be as meaningful, if not more meaningful, than a marriage relationship. And if I were to have a child as the result of such a relationship, I’d have someone to love and who loves me— somehow things would work out.

These five beliefs seem to be increasingly accepted in the United States and many other countries and significantly drive the declining marriage and birth rates and the rise of cohabitation and out-of-wedlock births. Furthermore, these beliefs are largely based on the assumption that your personal needs and happiness should drive decisions around marriage and children.

In addition to these cultural trends, research has described millennials as being more individualistic and narcissistic than prior generations;47 lacking empathy48 and teamwork skills;49 unaccepting of personal responsibility for failure;50 and being emotionally needy, constantly needing praise and validation.51 Although exceptions to this psychological profile of millennials certainly exist, the research suggests a perfect storm as these individuals navigate cultures that support the values of individualism, self-absorption, and personal accomplishment rather than focusing on others—thus leading to a lack of interest in marriage and having children. We know that behavior is a function of individuals with certain values interacting with the cultural values that surround them. And, of course, a recursive, self-reinforcing, dynamic occurs: the culture influences individuals to adopt certain values, and individuals who adopt those values become role models of those values for the broader society.

This individualism is behind the relatively recent phenomenon of “sologamy”—marrying yourself. Although the ceremony carries no legal weight, for some it does have symbolic significance. The BBC, in reporting a story on a sologamous marriage in Italy, interviewed the woman, Laura Mesi, who married herself. She said: “I firmly believe that each of us must first of all love ourselves. You can have a fairy tale even without the prince.”52 The BBC noted that such “marriages” are believed to have initially begun in 1993, and while not large in number, seem to be growing in popularity.

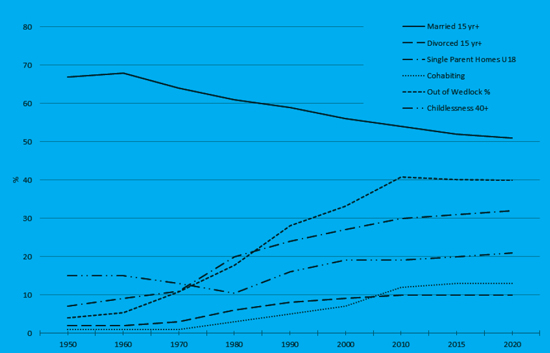

Figure 2.1 presents a visual representation of the trends from 1950 to the projected year 2020. To put these trends in the same figure we needed to calculate them in terms of percentages. In addition to the five trends—marriage rates (percent over age fifteen who are married), divorce rates (percent over age fifteen who have been divorced), birth rates (percent of women over forty who are childless), cohabitation rates (percent who are cohabiting), and out-of-wedlock birth rates (percent of out-of-wedlock births)—I have added an additional dimension, that of “single-parent homes with children under eighteen,” which is typically a function of divorce or out-of-wedlock births. Households with only one parent have increased in the United States from under 10 percent in 1950 to over 30 percent today.

Figure 2.1 US Trends on Six Dimensions of Family Capital Factors

The trends described in figure 2.1 do not necessarily apply to all countries and cultures. But, in general, the trends of other countries are similar.

Asian Americans, at 12 percent self-employment, are better able to succeed in starting and growing new businesses. Data from various sources offer explanations as to why. Recent data from the Survey of Minority-Owned Business Enterprises (SMOBE), the Survey of Business Owners (SBO), the Survey of Characteristics of Business Owners (CBO), and the Current Population Survey (CPS) provide important insights concerning family demographics and entrepreneurial activity within certain racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Using data from these sources, Robert Fairlie and Alicia Robb summarize the basic findings of their study related to business ownership and firm outcomes for whites, Asian Americans, Hispanics, and African Americans:53

» African Americans and Hispanics are much less likely to own a business than are whites or Asian Americans. CPS data indicate that 12 percent of Asian American workers, 11 percent of white workers, 7 percent of Hispanic workers, and only 5 percent of black workers own their own business.

» Asian American-owned firms “clearly have the strongest performance among all major racial and ethnic groups.” Asian American-owned firms are 16 percent less likely to close, 21 percent more likely to have profits of at least $10,000, and 27 percent more likely to hire employees; moreover, they have mean sales 60 percent higher than firms owned by whites.

» African American-owned companies have lower sales and profits, hire fewer people, and have higher closure rates than white-owned firms. Hispanic firms also have lower sales and hire fewer employees than white-owned firms.54

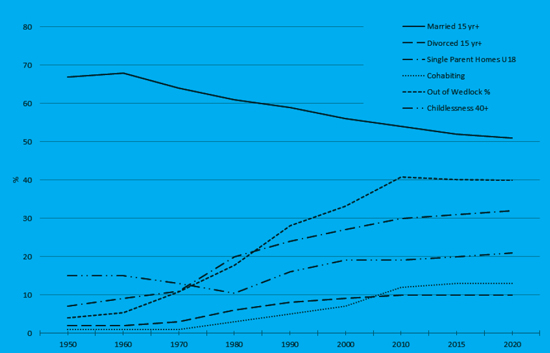

The trends in terms of marriage, cohabitation, divorce, birth rates, and out-of-wedlock birth rates are affecting access to family capital in each of these groups. Table 2.1 (opposite) summarizes these differences. The data come from a variety of sources at different times, given that finding accurate family data based on race is fairly difficult. Most of the data in table 2.1 are from several years ago when I started studying the impact of race on self-employment. However, 2016–2017 statistics from the US Census and Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that the differences between the racial groups along these five dimensions have remained fairly stable over time.55

It is not surprising, given our theory linking family capital to entrepreneurial activity, that Asian Americans have historically had high rates of self-employment and create larger and more successful businesses than do the self-employed in the other racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Asian Americans have the second highest marriage rate (71.6 percent), the second highest birth rate (17.2 percent), and the lowest rates of divorce (4.9 percent), out-of-wedlock births (26 per 1,000), and cohabitation (5 percent). In short, Asian Americans have each of the five factors affecting family capital going in the “right” direction for them. In comparison, African Americans have the lowest marriage rate (53.9 percent), are third in birth rate (16.9 per 1,000), are second in out-of-wedlock births (72 per 1,000) and have the highest divorce (11.5 percent) and cohabitation (17 percent) rates. Whites are fairly similar to Asian Americans but are more likely to cohabit and be divorced. Hispanics did well in comparison to the other groups on dimensions such as divorce rate and cohabitation, but they have an extremely high number of out-of-wedlock births (106 per 1,000). While these data obviously don’t tell the whole picture of why certain groups are more entrepreneurial than others, they do suggest that those individuals with more stable families with access to family capital will be more likely to launch a business and make it successful over time. Economist and Nobel laureate Gary Becker supports this notion that the family is important to economic development when he writes, “The family is still crucial to a well-functioning economy and society, and I believe—in the long run—that those economies that will advance most rapidly will tend to have strong family structures.”56

Table 2.1: Racial/Ethnic Groups in the United States in Regards to Marriage, Cohabitation, Divorce, Birth Rate, and Out-of-Wedlock Births

Besides changes in American families over the years, institutional racism has also played a role in inhibiting minority groups, particularly African Americans, from creating new enterprises and generating wealth. In the case of African Americans, the disadvantages created by slavery are inextricably connected to the destruction of their family capital. The ability of slave owners to buy and sell family members disrupted family ties. Although informal “marriages” were performed, the law forbade slaves from formally marrying. Moreover, slavery obliterated African Americans’ sense of identity in a tribe or clan, which was an integral part of family life in Africa. This further undermined family social capital and stymied the transfer of family capital across generations. Slavery made it difficult for African Americans to even identify themselves as part of a family and thus they often took their master’s surname to provide them with some connection to a family, albeit not their own. African Americans had few familial resources to help themselves and their loved ones and thus, out of necessity, became dependent upon the slave owners, the government, or other institutions—curbing their ability to become self-reliant. The net effect on the African American community was a lack of resources to start and grow businesses and provide for their families. Thus, the disruption of family relationships to keep minority groups in a subservient position has played an important role in racism in America. The complete story of slavery and racism and its impact on families and family capital is too long and complex to be considered here, but its recognition is important. Moreover, current family patterns within the African American community, some of which may be a function of its history, continue to make it difficult for African Americans to generate family capital.

The trends in the United States regarding marriage, cohabitation, fertility rates, divorce, and out-of-wedlock births tend to mirror global trends. Marriage rates are declining in much of the industrialized world. In fact, despite its recent decline in marriage, the United States generally leads the developed world in marriage rates—9.8 per 1,000 people per year. Other selected countries’ marriage rates per 1,000 are as follows: Russia, 8.9; Portugal, 7.3; Israel, 7; New Zealand, 7; Australia, 6.9; Denmark, 6.1; Greece, 5.8; Japan, 5.8; Italy, 5.4; France, 5.1; Finland, 4.8; and Sweden, 4.7.57

The decline in birth rates is similar. For example, various studies project that given current birth rates Europe will have approximately forty to one hundred million fewer people by 2050.58

Here’s a sampling of fertility rates in developed countries: France, 2.08; United Kingdom, 1.91; Chile, 1.87; Australia, 1.77; Russia, 1.61; Canada, 1.59; China, 1.55; Italy, 1.40; Ukraine, 1.29; Czech Republic, 1.27; Taiwan, 1.10; and Singapore, 0.78.59 Eleven countries with the highest birth rates are in Africa; however, poor nutrition and disease (particularly AIDS) have led to a significant number of single-parent families there, in addition to a significant number of orphans. In South Africa alone 5.6 million people are infected by AIDS, with 310,000 dying of the disease each year.60 AIDS has left 11 million orphan children in sub-Saharan Africa.61

Mara Hvistendahl’s book Unnatural Selection62 and Valerie Hudson’s and Andrea den Boer’s book, Bare Branches,63 highlight a very troubling fact—due to selective abortions and female infanticide in Asia (mostly in India and China), there are well over one hundred million fewer women than men in Asia. Thus, many young men in Asia will not be able to find a mate who could provide them with family capital or help them found and perpetuate a business.

Divorce, while increasingly common, varies dramatically across the world. The highest divorce rates are in Europe (e.g., Sweden, 54.9 percent), Australia (46 percent), the United States (45.8 percent) and Russia (43.3 percent), while divorce rates in the Middle East (e.g., Turkey, 6 percent) and Asia (e.g., India, 1.1 percent) are much lower.64 Higher divorce rates can result in fewer family businesses and fewer family firms passed to the next generation.

Much like fertility rates, out-of-wedlock births vary dramatically by country. In Japan, for example, only 2 percent of all births are out-of-wedlock. Other countries in Asia (e.g., Korea) also have a low rate. However, in countries elsewhere, particularly in Europe, the rates are significantly higher: Italy, 30 percent; Ireland, 35 percent; Netherlands, 50 percent; Sweden, 55 percent; Iceland, 66 percent. In South America, Colombia is at a staggering 84 percent.65 Furthermore, out-of-wedlock birth rates have increased dramatically over the past decades in certain countries. For example, in 1970 the out-of-wedlock birth rate in the Netherlands was less than 3 percent but had increased to about 50 percent by 2016.66

Worldwide trends regarding the family suggest that families in Asia are generally more stable than those in the West—they have more marriages, fewer divorces, and fewer out-of-wedlock births. However, family size and fewer women available for marriage could negatively affect Asian family capital in the future. In North America, Europe, and Australia, family size, divorce, marriage, and out-of-wedlock birth rates continue to undermine familial capital. In Africa and South America, the picture is less clear. Birth rates in Africa and South America are relatively high compared to other continents, but out-of-wedlock births, divorce, and marriage rates are problematic for family capital in many countries on these continents.

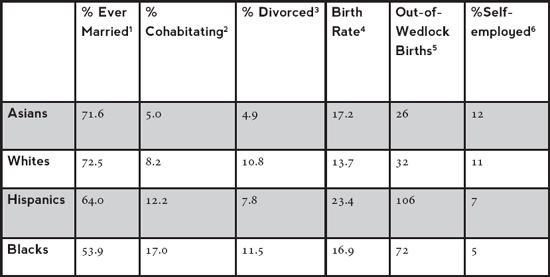

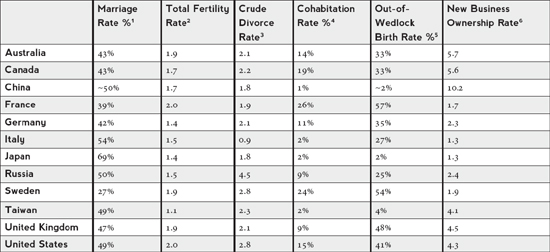

So do these family trends affect entrepreneurial activity in the various countries worldwide? Data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) suggest a connection.67 On a regular basis, GEM researchers gather data about entrepreneurship intentions and business start-up rates worldwide. Comparing start-up rates and entrepreneurial activity across nations is very difficult because of differences in political systems, economies, cultures, and so forth. However, I decided to do a gross comparison of industrialized countries using the five dimensions related to family capital—marriage, divorce, cohabitation, fertility, and out-of-wedlock births—to see if there might be some connection between these factors and new business ownership rates.68 The countries included in the panel are Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, Sweden, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the United States (see table 2.2).

As shown in the table, China has the highest new business ownership rate, partly due to the entrepreneurial spirit among the Chinese and their recent changes to a more capitalist economy. But they also have more stable families compared to the other industrialized nations, with high marriage rates, relatively low divorce rates, and very low cohabitation and out-of-wedlock birth rates. The only problematic area for the Chinese is the low birth rate, which is being partly addressed by the easing of the one-child policy in China. In contrast, some of the European countries listed in table 2.2 such as France and Sweden have high out-of-wedlock birth rates (57 and 54 percent, respectively) and high cohabitation rates (26 and 24 percent). Both have relatively low marriage rates (39 and 27 percent). New business ownership rates in those countries are some of the lowest in the world at 1.7 and 1.9 percent. Two European countries seemingly somewhat better than France and Sweden along the five family capital dimensions are Germany and Russia, which have a 2.3 and a 2.4 new business ownership rate, respectively. Russia has a high marriage rate but also a high divorce rate—one of the highest in the world—while Germany has lower cohabitation and out-of-wedlock birth rates than do France and Sweden. Italy and Japan, on the other hand, have lower new business ownership rates than the other countries, but seem to have a somewhat more stable family structure (lower cohabitation and lower out-of-wedlock births) than some other countries, although both have very low fertility rates. Thus, there is clearly more to the story of entrepreneurship in Italy and Japan than is shown by these data.

Table 2.2: Family Patterns in Industrialized Countries and New Business Ownership

−Estimates based on best data available from China.

The United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia had higher new business ownership rates than Europe did. In general, these countries had relatively low cohabitation rates, modest divorce rates (with the exception of the US), and marriage rates ranging from 43 to 49 percent, but somewhat high out-of-wedlock birth rates (ranging from 33 to 48 percent). Thus these countries have both strengths and weaknesses in family capital. Taiwan appears to have stable families and a fairly robust new business ownership rate (4.1 percent)—but it has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world (1.1 per 1,000), which would clearly undermine family capital.

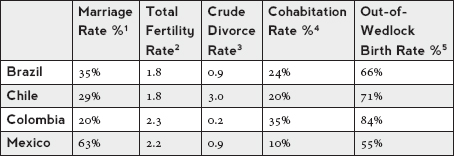

Table 2.3 Family Demographics from Selected Latin American Countries

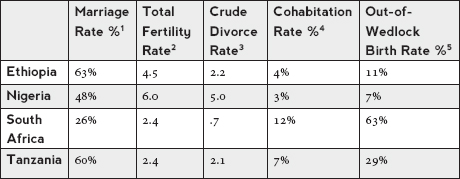

In tables 2.3 and 2.4 we have a description of the five dimensions affecting family capital for the Latin American countries of Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico and the African countries of Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Africa, and Tanzania. Data on business start-up are much less trustworthy in these countries since many start-ups are out of necessity and aren’t what would be called true entrepreneurial ventures. Nevertheless, Latin America and Africa have high poverty rates and poor economic growth compared to the rest of the world. The poverty implies fairly low access to family capital to launch a new business or provide a safety net for family members when times are difficult.

The data from table 2.3 on Latin America exposes some of the problems. First, there is a very high out-of-wedlock birth rate ranging from a high of 84 percent in Colombia to 55 percent in Mexico. Marriage rates, with the exception of Mexico, are also quite low, with modest cohabitation rates ranging from 10 percent in Mexico to 35 percent in Colombia. Fertility rates are modest as are divorce rates, with the exception of Chile. In many Latin American countries divorce is costly so leaving one’s spouse without getting a divorce is common. Hence, we often find a higher cohabitation rate in these countries versus other countries where divorce is easy to obtain. For those who separate from their spouse and cannot legally marry someone else without a divorce, a common law/cohabiting relationship may seem their only option. Thus, the state of families and family capital in Latin America suggests a difficult road ahead to stimulate economic activity and move people out of poverty.

The story of families in sub-Saharan Africa is fairly complex, because not only is family structure being torn apart from negative political and social conditions but also civil wars, AIDS, and other diseases have left millions of children as orphans—making access to family capital virtually impossible for them. In the four countries listed, you will note the higher birth rates versus Latin America and the industrialized nations. Nigeria, at 6.0 children per woman, has one of the highest birth-rates in the world but also has a high divorce rate. South Africa, on the other hand, has a low marriage rate compared to the other countries and thus, not surprisingly, a higher cohabitation and out-of-wedlock birth rate. The history of slavery and colonialism in Africa along with the emergence of brutal dictators and civil wars have clearly disrupted family structures and family capital and stymied economic development in African nations.

Table 2.4 Family Structure in Sub-Saharan Africa (selected countries)

While studying the challenges countries have in developing family capital, I became interested in the special problems facing countries in sub-Saharan Africa. In the spring of 2017, I traveled to Africa with Faculty Development in International Business (FDIB), a program for business school academics sponsored by the US government, visiting South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Swaziland.69 My five days in Swaziland were particularly interesting from a family capital perspective given the country’s challenges. I gathered information about Swazi society from local Swazi business leaders, government representatives, and Swazi academics, as well as US diplomats stationed there.

Swaziland is a small country of about 1.4 million people located at the east end of southern Africa, bordered by South Africa on the north, south, and west, and by Mozambique on the east. The country is the homeland of the Swazi tribe and has been ruled by kings for many generations. The minimal industry mainly relates to sugarcane, tourism, and handicrafts, but the country manufactures and distributes Coca-Cola concentrate for all of southern Africa. (Coca-Cola relocated its plant to Swaziland from South Africa many years ago when companies began boycotting South Africa due to apartheid.) Subsistence farming is the dominant practice in Swaziland, which provides little income for Swazis; therefore, the government depends heavily on customs duties from the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and worker remittances from Swazis who have left Swaziland to find work in other countries, primarily South Africa.

In terms of family capital, the Swazi culture discourages safe-sex practices such as condom use and monogamous marriages, and it encourages a man to impregnate as many women as possible. Moreover, significant social stigma is attached to anyone with a sexually transmitted disease (primarily HIV/AIDS), which discourages people from being tested and seeking treatment. These beliefs and practices have led to Swaziland having the highest incidence of HIV/AIDS in the world (31 percent of the population), a life expectancy of 49 years, low marriage rates, high out-of-wedlock birth rates, many orphans (one in four children, primarily due to AIDS), and a low percentage (22 percent) of children growing up in two-parent families. However, polygamy is found among the well-to-do in Swazi society.

The king and the royal family also play a role in shaping Swazi promiscuity and marriage instability. The previous king, Sobhuza II, was born in 1899 and was crowned as an infant after his father died. Sobhuza II had 70 wives and 210 children (and thousands of grandchildren and great grandchildren). One of the king’s practices was to have virgins (typically in their teens) paraded before him periodically so that he could choose one of them as a future wife. However, once chosen to be a future wife, the girl would need to be impregnated by Sobhuza II before becoming eligible for marriage to the king. This practice has continued with the current king, Mswati III, who has 15 wives (although the actual total is debatable). Mswati III’s mother had not been officially married to Sobhuza II before he died, so to legitimate Mswati III’s birth and status a marriage ceremony was performed for Mswati’s mother and Sobhuza II’s corpse—an unusual marriage ceremony to say the least. The king rules Swaziland by edict (although the country has a nominal constitution) and he has a $200 million trust fund of which about $61 million is used each year to support his family. (The king and the principal wives all have elaborate palaces.) As for the rest of the country, 63 percent of Swazis live in poverty and 29 percent live in extreme poverty, meaning they live on less than one dollar per day.

Swaziland has beautiful scenery and friendly people, but the outcomes associated with the breakdown of the family in Swaziland are unmistakable: little entrepreneurial activity, high unemployment (about 40 percent), a high poverty rate (63 percent), and a national health crisis associated with sexually transmitted diseases.

Although Swaziland is an extreme case, data from other countries in Africa, South America, and other parts of the world suggest that family capital is increasingly scarce. This does not bode well for the economic health and stability of many countries throughout the world.

Chapter Takeaways

» Cultural narratives in the United States regarding marriage and children are having a negative impact on family capital.

» Family capital, or the lack of it, affects entrepreneurial activity worldwide.

» Family capital among nations, although difficult to ascertain, can be shown using rudimentary data.

» Generally, worldwide trends do not bode well for family capital.

1. Paul C. Rosenblatt et al., The Family in Business (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1985).

2. Robert W. Fairlie and Alicia M. Robb, Race and Entrepreneurial Success (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008).

3. Sanders, J., & Nee, V. 1996. “Social Capital, Human Capital, and Immigrant Self-Employment: The Family As Social Capital and the Value of Human Capital,” American Sociological Review 61 no. 2 (1996): 240–41.

4. Fairlie and Robb, Race and Entrepreneurial Success.

5. Roger Peay and W. Gibb Dyer Jr., “Power Orientations of Entrepreneurs and Succession Planning,” Journal of Small Business Management 27 no. 1 (1989): 47–52.

6. Estimated Median Age at First Marriage, by Sex: 1890 to the Present prepared by the United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/families/marital.html.

7. Marital Status of the Population 15 Years and Over, by Sex, Race and Hispanic Orgin: 1950 to Present prepared by the United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/families/marital.html.

8. Kim Parker and Renee Stepler, “As US Marriage Rate Hovers at 50%, Education Gap in Marital Status Widens,” Pew Research Center, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/14/as-u-s-marriage-rate-hovers-at-50-education-gap-in-marital-status-widens.

9. Howard E. Aldrich and Jennifer E. Cliff, “The Pervasive Effects of Family on Entrepreneurship: Toward a Family Embeddedness Perspective,” Journal of Business Venturing 18 (2003): 581.

10. Howard E. Aldrich and Nancy Langton, “Human Resource Management and Organizational Life Cycles,” Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research (1997): 349–357.

11. Ivan Light and Steven J. Gold, “Ethnic Economies and Social Policy,” Research in Social Movement, Conflict and Change 22 (2000): 87.

12. Light and Gold, “Ethnic Economies and Social Policy,” 87.

13. Lloyd Steier and Royston Greenwood, “Entrepreneurship and the Evolution of Angel Financial Networks,” Organization Studies 21 (2000): 163–92.

14. Fairlie and Robb, Race and Entrepreneurial Succes s, 92.

15. Lyman Stone, “American Fertility Is Falling Short of What Women Want,” New York Times, February 13, 2018.

16. James S. Coleman, “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital,” American Journal of Sociology 94 (1988): S95-S120.

17. Fairlie and Robb, Race and Entrepreneurial Succes s, 187.

18. P. R. Amato, “The Impact of Family Formation Change on the Cognitive, Social and Emotional Well-Being of the Next Generation,” Future of Children 15 no. 2 (2005): 77.

19. Ibid., 77.

20. Jeremy Arkes, “The Temporal Effects of Parental Divorce on Youth Substance Use,” Substance Use & Misuse 48 no. 3 (2013): 290–97, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23363082.

21. Overdose Death Rates prepared by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

21. Amato, “The Impact of Family Formation Change on the Cognitive, Social and Emotional Well-Being of the Next Generation,” 75–96.

23. Bradford Wilcox et al., “When Marriage Disappears: The Retreat from Marriage in Middle America,” State of Our Unions (2010).

24. Linda J. Waite, “Does Marriage Matter?” Demography 32 no. 4 (1995): 483–507.

25. Scott M. Stanley, Sarah W. Whitton, and Howard J. Markman, “Maybe I do: Interpersonal Commitment and Premarital or Nonmarital Cohabitation,” Journal of Family Issues 25 (2004): 496–519.

26. Susan L. Brown, Wendy D. Manning, and Krista K. Payne, “Relationship Quality Among Cohabiting Versus Married Couples,” National Center for Family & Marriage Research 14 no. 3 (2014).

27. Sanders Korenman and David Neumark, “Marriage, Motherhood, and Wages,” Journal of Human Resources 27 no. 2 (1990): 233–255.

28. Lee A. Lillard and Linda J. Waite, “Till Death Do Us Part: Marital Disruption and Mortality,” American Journal of Sociology 100 no. 5 (1995): 1131–56.

29. Paul R. Amato and Alan Booth, A Generation at Risk: Growing Up in an Era of Family Upheaval (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

30. Linda J. Waite, “Social science finds: ‘Marriage matters’,” Responsive Community 6 (1996): 26–35.

31. Jeffrey H. Larson, 2001. “The Verdict on Cohabitation Vs. Marriage,” Marriage & Families 4 no. 3 (2001), http://marriageandfamilies.byu.edu/issues/2001/January/cohabitation.htm.

32. Susan L. Brown, “Family Structure and Child Well-Being: The Significance of Parental Cohabitation, Journal of Marriage and the Family 66 (2004): 351–67.

33. Robert Whelan, Broken Homes and Battered Children: A Study of the Relationship Between Child Abuse and Family Type (London: Family Education Trust, 1994).

34. Elizabeth H. Pleck, Not Just Roommates: Cohabitation After the Sexual Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

35. Daniel T. Lichter, Richard N. Turner, and Sharon Sassler, “National Estimates of the Rise in Serial Cohabitation,” Social Science Research 39 no. 5 (2010): 754–65.

36. National Survey of Family Growth prepared by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/key_statistics/c.htm#currentcohab.

37. Alfred Demaris and Vaninadha Rao, “Premarital Cohabitation and Subsequent Marital Stability in the United States: A Reassessment,” Journal of Marriage and the Family 54 no. 1 (1992): 178–90.

Susan L. Brown, Wendy D. Manning, and Krista K. Payne, “Relationship Quality Among Cohabiting Versus Married Couples,” Journal of Family Issues 38 no. 12 (2014): 1730–1753.

38. L. L. Bumpass, T. C. Martin, and J. A. Sweet, “The Impact of Family Background and Early Marital Factors on Marital Disruption,” Journal of Family Issues 12 no. 1 (1991): 22–42.

Brown, Manning, and Payne, “Relationship Quality Among Cohabiting Versus Married Couples,”1730-53.

39. Ibid.

40. Marcia Carlson, Sara McLanahan, and Paula England, “Union Formation and Dissolution in Fragile Families,” Center for Research on Child Wellbeing 41 no. 2 (2004): 237–61.

41. Bradford Wilcox et al., “When Marriage Disappears: The Retreat from Marriage in Middle America.”

42. Recent Declines in Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States prepared by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db162.htm.

43. Andrew Cherlin, David C. Ribar, and Suzumi Yasutake, “Nonmarital First Births, Marriage, and Income Inequality,” American Sociological Review 81 no. 4 (2016): 749–70.

44. Ibid., 749–70.

45. Kathryn Vasel, “The Cost of the American Dream,” CNN Money, January 9, 2017, http://money.cnn.com/2017/01/09/pf/cost-of-raising-a-child-2015/index.html.

46. The quotes from the various celebrities can be found in the following two sources:

“Celebrity Marriage: Craziest Stuff Stars Say About Marriage,” Life, July 20, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/celebrity-marriage_n_1688174.html?slideshow=true#gallery/239768/17.

“23 Celebrities Reveal How They Feel About Not Having Kids,” Elle, September 14, 2017, http://www.elle.com/culture/celebrities/a35545/celebrities-not-having-kids-quotes.

47. Jean M. Twenge, W. Keith Campbell, and Elise C. Freeman, “Generational Differences in Young Adults’ Life Goals, Concern for Others and Civic Orientation, 1966–2009,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102 no. 5 (2012): 1045–62.

48. Sara H. Konrath, Edward H. O’Brien, and Courtney Hsing, “Changes in Dispositional Empathy in American College Students Over Time: A Metal Analysis,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 15 no. 1 (2011): 180–98.

49. Twenge, Campbell, and Freeman, “Generational Differences in Young Adults’ Life Goals, Concern for Others and Civic Orientation, 1966–2009,” 1045–62.

50. J. M. Twenge, L. Zhang, and C. Im, “It’s Beyond My Control: A Crosstemporal Meta-Analysis of Increasing Externality in Locus of Control, 1960–2002.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 8 no. 3 (2004): 308–19.

51. Martha Crumpacker and Jill M. Crumpacker, “Succession Planning and Generational Stereotypes: Should HR Consider Age-Based Values and Attitudes a Relevant Factor or a Passing Fad?” Public Personnel Management 36 no. 4 (2007): 349–69.

52. “Italy Woman Marries Herself in ‘Fairytale without Prince’,” BBC News, September 27, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-41413297.

53. Fairlie and Robb, Race and Entrepreneurial Success.

54. Ibid., 10.

55. Joyce A. Marlin et al., “Births: Final Data for 2016,” National Vital Statistics Reports 67 no. 1 (2018).

56. Gary Becker, “Human Capital,” Universidad de Montevideo, http://www.um.edu.uy/docs/revistafcee/2002/humancapitalBecker.pdf, p. 2.

57. United Nations Monthly Bulletin of Statistics, April 2001 prepared by the Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

58. https://www.ft.com/content/d54e4fe8-3269-11e8-b5bf-23cb17fd1498

59. World Factbook 2012 prepared by the Central Intelligence Agency.

60. World Factbook 2011 prepared by the Central Intelligence Agency.

61. https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-social-issues/key-affected-populations/children

62. Mara Hvistendahl, Unnatural Selection: Choosing Boys Over Girls and the Consequences of a World Full of Men (New York: Public Affairs, 2012).

63. Valerie M. Hudson and Andrea M. den Boer, Bare Branches: The Security Implications of Asia’s Surplus Male Population (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004).

64. World Divorce Statistics prepared by Divorce Magazine, October 14, 2014, www.divorcemag.com/statistics/statsWorld.shtml.

65. “Share of Births Outside of Marriage,” Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2018), https://www.oecd.org/els/family/SF_2_4_Share_births_outside_mar-riage.pdf.

66. Ibid.

67. D. Kelley, S. Singer, and M. Harrington, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: 2011.

68. Data on marriage, divorce, fertility, cohabitation, and out-of-wedlock births come from the following sources: World Family Map, 1998–2013; United Nations World Marriage Data; Sustainable Demographic Dividend prepared by the Social Trends Institue—Mexico, 2006 and Chile, 2010; United Nations Statistical Division.

69. Information about Swaziland was gathered from the following sources: World Factbook 2015 prepared by the Central Intelligence Agency; Mindy E. Scott et al., “World Family Map 2015,” Institute for Family Studies, http://worldfamilymap.ifstudies.org/2015; Statistics prepared by Unicef, www.unicef.org/infobycountry/swaziland_statistics.html; Ambassador Lisa Peterson and the U.S. embassy staff in Swaziland, May 18, 2017; and Robert Rolfe, Professor, University of South Carolina.

Historical Marital Status Tables prepared by the United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/families/marital.html.

Historical Families Tables prepared by the United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/families/families.html.

Casey E. Copen et al., “First Marriages in the United States: Data From the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth,” National Health Statistics Reports 49 (2012), https://www. cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr049.pdf and https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/key_statistics/c.htm#chabitation (This data was the least available so years 1950–1970 were extrapolated at 1% from the data).

National Vital Statistics Reports, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/statab/t991x17.pdf, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_03.pdf, and https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_09.pdf.

Gretchen Livingston and D’Vera Cohn, “Childlessness Up Among All Women; Down Among Women with Advanced Degrees,” Pew Research Center, June 25, 2010, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/06/25/childlessness-up-among-all-women-down-among-women-with-advanced-degrees.

“The Rise of Childlessness,” The Economist, July 27, 2017, https://www.economist.com/news/international/21725553-more-adults-are-not-having-children-much-less-worrying-it-appears-rise.

1. US Census, 2009 (Average of Data on Men and Women).

2. Tivia Simmons and Martin O’Connell, “Married-Couple and Unmarried-Partner Households: 2000.” Census 2000 Special Reports. U.S. Census Bureau 2003. Reports number of children born per 1000 women of child-bearing age.

3. US Census 5-Year community study, Jan. 1, 2005-Dec. 31, 2009.

4. National Vital Statistics Reports for 2007, Vo. 58, No. 4.

5. Stephanie J. Ventura, Changing Patterns of Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States, NCHS Data Brief, no. 18, May 2009. Reports number of births per 1000 non-married women of childbearing age.

6. Fairlie and Robb, 2008.

1. Percentage of married adults of reproductive age (18-49).

2. Number of children who would be born per woman if she lived to the end of her childbearing years and bore children at each age in accordance with prevailing age-specific fertility rates.

3. Total number of divorces per 1,000 population.

4. Percentage of cohabitating adults of reproductive age (18-49).

5. Percentage of all live births to unmarried women.

6. Percentage of individuals aged 18–64 who are currently an owner-manager of a new business, i.e., owning and managing a running business that has paid salaries, wages, or any other payments to the owners for more than 3 months but not more than 42 months.

1. Percentage of married adults of reproductive age (18-49).

2. Number of children who would be born per woman if she lived to the end of her childbearing years and bore children at each age in accordance with prevailing age-specific fertility rates.

3. Total number of divorces per 1,000 population.

4. Percentage of cohabiting adults of reproductive age (18-49).

5. Percentage of all live births to unmarried women.

1. Percentage of married adults of reproductive age (18-49).

2. Number of children who would be born per woman if she lived to the end of her childbearing years and bore children at each age in accordance with prevailing age-specific fertility rates.

3. Total number of divorces per 1,000 population.

4. Percentage of cohabitating adults of reproductive age (18-49).

5. Percentage of all live births to unmarried women.

You don’t choose your family. They are God’s gift to you, as you are to them.

Desmond Tutu, Nobel Peace Prize winner