LET ME PROPOSE, as a beginning point, that we should all accept the premise that a residential liberal arts education is the gold standard to which higher education should aspire. The challenge we face in an increasingly economically challenging tim e is: how do we preserve as much of that gold standard as we possibly can? We understand, just like gold jewelry, there will be 24-karat, 18-karat, and 10-karat organizations, and then there will be those that simply have a little gold plate on the outside. I would like to ask what we can do to preserve the best possible program for the highest number of students.

Let us start with the question that Professor Bowen raised yesterday. Is there a cost problem in higher education? I think the answer to that is undeniably there is a cost problem but with many caveats around the structure of that cost problem. In a wonderful book, Why Does College Cost So Much?, two colleagues, Professors Robert B. Archibald and David H. Feldman, plotted lines of the growing cost of higher education and demonstrated that in fact, higher education had much the same cost structure as other service industries that relied on highly educated people. The good news was that we were no more expensive in terms of cost growth than dental services, and we were better than lawyers! However, we were worse than doctors in terms of cost growth, and I will come back to this as a way of thinking about what we could do about the cost challenges in higher education.

The core problem is that the sticker price of a college education is going up faster than the consumer price index (CPI) and even the wage inflation index; the difficulty is compounded by what has happened with family income and family dynamics. Professor Bowen pointed out yesterday the flattening of family income that has occurred over the last decade, but there is another issue that I think is not mentioned very often but played a significant role in the period from the 1960s through to the 1990s, and that was the reduction in family size, which meant that families actually had more money per child to spend on higher education. But family size has stopped shrinking more recently. Both factors have contributed to making affordability even more challenging.

Just how fast is the sticker price going up? Amazingly, despite the existence of antitrust agreements, many higher education institutions seem to raise their tuition at remarkably similar rates. The feedback effect is clearly operating here. If you look at those numbers over a thirty-year period, Stanford’s tuition has gone up 2.8 percentage points per year above CPI, and over a total of thirty years, that is an astonishing differential growth rate. The relationship between sticker price, net price, and expenses is complex.

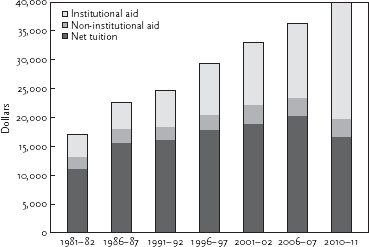

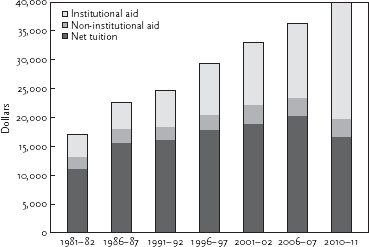

Let’s start with net tuition because it is an important metric. Net tuition takes the average tuition paid by a student (before financial aid) and subtracts the average financial aid. Only institutional or federal scholarships are counted as financial aid; loans are not. (Net tuition is a slightly misleading figure because recently, as the number of low-income students has gone up, and lower-income families have grappled with the cost of room and board, many institutions have begun subsidizing room and board. In a net tuition calculation, this subsidy appears to reduce tuition. For residential institutions, net total cost of attendance may be a better metric.)

Figure 5 List price, financial aid, and net tuition at Stanford over thirty years, compiled from Stanford’s university budgets

If you look at Stanford’s net tuition (figure 5), it has gone up in the most recent thirty-year period at a rate that is 1.4 percentage points above CPI, which means that financial aid increases have covered 50 percent of the list-price tuition growth. The most interesting period, however, is between 2006 and the present, when net tuition actually dropped to a level that roughly equals what it did in 1994 inflation-adjusted dollars. There actually was a decrease in net tuition enabled by a significant increase in institutional financial aid. That financial aid brought our net tuition number down to about $16,500, compared with a sticker price of just over $40,000. This, of course, is a Stanford number. You can think about financial aid among the private institutions as a three-tier system, with Stanford and most of the Ivy League in the top tier. The next tier is a group of institutions which give significant amounts of financial aid but perhaps not as much, particularly at some of the upper income levels, that is, in the $100,000 to $150,000 range of family income. Then there is a group of universities and colleges that cannot possibly provide this level of financial aid; most of them are characterized by the fact that 75 percent or more of their revenue comes directly from tuition dollars. The only way they can significantly raise their financial aid package in that third tier is by subsidizing one student’s financial aid using the sticker-price tuition payments of another student.

Now, total cost of attendance is not $40,000, which is only tuition, but closer to $52,000, including room and board and other associated expenses, and net cost of attendance is not $16,500 but $28,600. There is a significant difference between net tuition and net cost of attendance because many low-income students are getting significant amounts of financial aid toward their room and board and other costs. Nonetheless, net total cost of attendance (that is, the total cost of attendance after all financial aid sources are removed) is still lower than it was about a decade ago. Remember, this is the high end of the financial aid spectrum. You might ask how this significant increase in financial aid has been funded and whether or not such funding is sustainable. It has, as Professor Bowen observed yesterday, been funded by a significant growth in endowment. Endowment has grown on a per-student basis at roughly 6 percentage points over the higher education price index (HEPI), which tends to be 0.5 to 1 percentage point over the wage inflation index. Over a long period of time, HEPI has grown at a rate 1.5 percentage points above increases in the CPI. A key question is whether this record of strong endow ment growth will continue. The rapid growth above inflation and payout has dramatically shifted the university budget over thirty years: in 1981–82, 6 percent of our budget came from endowment income. This past year (2011–12), 21 percent of our budget came from endowment income.

[Audience question] Does that include research expenses?

Yes, that includes research in the overall budget. Externally funded research fell from 42 percent to 33 percent over a comparable period, with endowment making up most of that difference, along with clinical income from the medical school. Untangling the finances when you have a medical school is difficult, but we can do it, at least approximately. Because universities archive lots of information, you can actually go back and get the budget of thirty years ago, and while not all the fund sources are identical, you can do a fairly good comparison over a long period.

It is the growth in endowment that has allowed the financial aid programs to increase significantly. Nonetheless, we, like many other institutions, are currently paying a significant fraction (roughly 25 percent) of our undergraduate financial aid budget out of temporary reserves, for the simple reason that we are in this recovery process from the 2008 financial crisis and recession, which drove down the value of the endowment. There is also a lingering effect in terms of family income and assets, which has increased our financial aid demands by about $10 million a year.

The public institutions are in a much more complicated situation. They have gone through a series of annual budget cuts, amounting to a significant fraction of their overall subsidy from the state. Overall, the average net tuition in inflation-adjusted dollars is roughly where it was in the mid-1980s, but the path over the last twenty-five years has not been smooth. In the 1980s, as state budgets grew, more and more money went into higher education. The net cost for attendance actually dropped from 1985 until the late 1990s, and then it began a steep uphill rise. Part of the public reaction that we see is to this steep increase that has occurred over the past ten to fifteen years. For better or worse, a series of zero or below-inflation increases in the 1980s and early 1990s significantly increased the dependence of the educational budget on the states. The problem occurs now, when increases of 20 to 25 percent are required to make up for decreases in state subsidy. Had tuition been raised at same rate as the wage inflation index, the problem and sense of crisis would be smaller.

The average grants and average loans for college students have grown about equally over time, so while there is a lot of angst over loans, the case is way overstated, in my view. Professor Bowen alluded to the New York Times article that was focused on finding the worst cases. Today, 73 percent of the students who attend nonprofits graduate with a debt balance of less than $25,000, and roughly 40 percent graduate with less than $10,000 of debt. There is a problem, which is at the for-profit institutions; I will return to this shortly.

The overall budget problem at public institutions is serious, and I am pessimistic about the possibilities for fixing it. On average, the public research universities have seen about a 15 percent real decrease in their per-pupil funding. There are lots of alternative numbers that get quoted. A percentage of the total budget that the state pays is frequently used, but it is not a good indicator of the state’s investment in undergraduate education, because the research establishments have grown so large.

Why have states decreased the per-student funding by 15 percent? Let’s put aside the 2008 financial crisis and its particular impact on state pensions, since much of that is yet to be accounted for. There is another insidious factor, and that is the rising Medicaid spending, and that has gone from roughly 0.2 percent to roughly 0.9 percent of the average state budget. This quadrupling in a period of thirty years has made other investments more difficult. This gets back to a point that Professor Bowen made yesterday: How do we, as a society, think about investing the tax revenues that we have? We have to make an important set of decisions, because entitlements will consume every dollar of tax revenue unless we tame their growth. Both the states and the federal government will be affected by these trends.

While I think we still have good affordability at the present time, we do have a growing problem: full sticker price is going up significantly faster than inflation, and the revenue sources that have allowed us to subsidize that list price (rapid growth of endowment in the case of the privates and state financing in the case of the publics) are both endangered. Thus, unless we do something significant, more students will be paying closer to sticker price, and that price will continue to escalate faster than family income.

So why is sticker price going up so fast? Professor Bowen touched on the key issues: wages, driven by the competition for an elite workforce. Faculty salaries have gone up faster than wages for most other workers in this country. Those of us who have been in the academy long enough realize that, financially, life is much more pleasant now than it was thirty years ago. Of course, the labor market for faculty largely drives this, and I think trying to swim upstream against the market, whether you are capping wages or you are capping the price of gasoline, does not work well.

Second, we have seen few or no productivity gains in higher education, at least as measured in traditional ways (e.g., dollars per student degree). Look at what has happened with other skilled workforces: doctors, dentists, and lawyers. They have all introduced assistant-level positions: physician assistants, paralegals, and dental hygienists, whose function is to offload the more expensive and more skilled worker, reducing the cost of a service. We sometimes pursue similar routes in the academy using adjunct professors and graduate students. Unfortunately, from a cost perspective, in most of our institutions, the offloading of faculty has been replaced not with other teaching requirements for that faculty member but with a growth in research as a fraction of the faculty member’s time.

I am going to come back to the costs imposed by research, but first let me talk about other services we provide for students. I think the real driver of cost in other services is the need for additional services with a student body that is very different than it was thirty or forty years ago. Contrary to the writing of some pundits, the expenditure is not for luxury suites and climbing walls. We do not offer a “Four Seasons experience”: our freshmen all share rooms with bathrooms down the hall, and I assure you that even though more than half of them had their own room and probably their own bathroom before they arrived here, they seem perfectly happy. But there are real costs, and I believe those costs come from the changing nature of the student body. We have a much larger fraction of low-income, first-generation students, and as Professor Bowen has argued, that is a good thing for the country, but he also mentions in his book Crossing the Finish Line that there are costs associated with these demographics.

Another issue, which I think all universities have experienced, is a rise in expenses related to student mental health. Students who previously never got to an elite college because they could not be competitive enough to get through high school at the top of their class can now get through high school with the help of various psychological support services, but they arrive at college facing many challenges. You could continue down the list. For example, community centers and ethnically themed dorms help acclimate and support students from diverse backgrounds. These services help create an environment which ensures that more students graduate and succeed, but they have additional costs associated with them.

There is another cost factor we can look at, and it is one that Professor Bowen alluded to: the cost of being a research institution. I have come to believe that as a country we are simply trying to support too many universities that are trying to be research institutions. The costs are truly significant, and incremental. Research is an activity that must be subsidized. I did a back-of-the-envelope calculation to try to look at the costs of having a research-oriented institution. I took Berkeley, a great institution, and my argument in no way should be taken to mean that we should stop having institutions like Berkeley; it is rather just an example of estimating what it costs to run a research institution. Down the road another twenty-five miles from here is San Jose State, an institution whose research budget from external sources is less than one-tenth of what Berkeley’s is. San Jose State is primarily an educational institution, with no PhD programs, simply a set of master’s programs and undergraduate programs. These are two institutions in the same region with a similar cost of living.

Let’s look at both student-faculty ratios and costs per student as metrics. I decided an adjustment was appropriate for PhD students, so I counted each PhD student at Berkeley as the equivalent of two undergraduates or master’s students. After making these adjustments, let’s consider the university budget per FTE, fulltime equivalent student. The mix of the students is not that different. Berkeley is 70 percent undergraduates and 30 percent graduate students. San Jose State is 80 percent undergraduates and 20 percent graduate students. Obviously, more of the Berkeley students are in PhD programs, but we have adjusted for that. The student-faculty ratio is very different, even after adjustment. The student-faculty ratio at Berkeley is 15:1, already roughly twice the ratio at the elite private universities, including Columbia, Stanford, Princeton, and Harvard. In comparison, the ratio at San Jose State is 26:1.

Now, let’s look at the budgets of the two institutions, after removing all government research dollars from their budgets to obtain a fairer comparison of educational costs. The Berkeley budget is more an estimate of how much they spend on the education mission. I summed tuition, the state’s subsidy, and one-half of their investment and gift income (assuming the other half was for the research mission). The costs are going to be sufficiently different that these estimates have little effect on the overall conclusion. San Jose has no endowment income and very little gift income, so you can omit those factors. What then is the cost per student when you do this quick kind of analysis? At Berkeley, the estimate is $26,800 per year. At San Jose State, it is $11,800 per year. My conclusion is that the cost of education in a research-intensive university is considerably higher; in fact, it appears that the ratio of costs exceeds even the differential student-faculty ratio. This difference in costs may be due to a variety of factors, from higher faculty salaries to smaller class sizes.

Now if you were to apply this analysis to other institutions, you would find the cost per student was much more varied. Berkeley may be more toward the high end and certainly has a track record of accomplishment that justifies the investment. But then, only a few research universities are of Berkeley’s caliber. I think we have to accept that nationally we may not be able to afford as many research institutions going forward as we have had, unless we can find alternative sources of funding. I do not think such funding is likely to come from the federal government, or from state government. The only place it is going to come from is a significant growth in philanthropy going to those institutions. This is an important issue for the country.

Getting back to Professor Bowen’s question, which came near the end of his lecture, we must ask ourselves: Do we have a crisis? I think we definitely have a cost problem, but I believe that our true crisis is not around costs but around college completion. If you look at completion rates, let us just put them in rough numbers. The public universities have completion rates of around 55 percent in six years for full-time incoming freshmen. (Given leaves, access to classes, and changes of majors, the six-year figure is probably appropriate.) For the private institutions, this number is just over 60 percent, and for four-year for-profits, the number is around 25 percent. These percentages are for students who start full-time. They ignore transfer students; adding students who transfer and complete adds as much as 10 percent to these graduation rates.

Now I propose that somebody should do an analysis I have never seen. Professor Bowen pointed out, in response to a question yesterday, the very positive return on investment accrued by somebody who completes a college degree. What is the return on investment for a student who does not complete a degree, if we include both college costs and the opportunity cost (incurred because the student isn’t working)? If we did that analysis, I think we would find a rather different number, one that would cause us to focus much more on completion. It is one thing for a student to finish a degree and come out with $25,000 of debt (the average incurred in 2011); it is another thing for a student to go to college and walk away with $10,000–$15,000 of debt and no degree to show for it. A number of studies have shown that the difference between completion and non-completion in terms of economic outcomes is very large. Students may certainly derive benefits from being in college, but for those who do not graduate it is hard to demonstrate the clear economic advantages associated with completing a degree.

The issue of student indebtedness and loan defaults blends the challenges of cost and completion. Increasing costs drive up loan indebtedness, and lack of completion leads to lower financial rewards and greater probability of default. Recent data show that the default rate on student loans is going up very slowly for the nonprofits, but it is soaring in the for-profit institutions: from FY 2006–07 to FY 2008–09, in a period of only two years, the for-profit default rate went from 9.8 percent to 15.4 percent. Students who do not graduate default on their loans at much higher rates, which is exactly what you could expect. This combination is a growing crisis, partly related to the cost of higher education. The mediocre completion rates, however, remind us that achieving lower costs by measures that decrease completion rates would be a bad trade-off.

Can we tame the problem of growing costs without damaging completion rates? I think we probably can at least moderate it. I do wonder whether or not the higher education community has the willingness and courage to face up to the problem proactively or whether they will simply react in incremental steps. For example, budgets fall because either states or parents reduce what they pay; then we decide to cut departments or cut programs instead of thinking about how we might move forward in a different way. There are things you could do. For example, you could raise student-faculty ratios, which could directly improve productivity, but I think we would all agree it would reduce quality and possibly endanger completion rates. Increasing the ratio would clearly improve productivity according to traditional measures. I suspect that higher education parallels the information-technology paradox mentioned by Professor Bowen. Increasing the student-faculty ratio is just one of many things that would reduce cost but would probably also reduce the quality of the experience. Measuring that quality loss is very difficult. I think many of the points raised by Professors Gardner and Delbanco had to do with the quality of the experience and what students learn from that entire experience; this is not something easily measured by student-faculty ratios or by standardized tests.

This afternoon, Professor Bowen will advance a hypothesis that I am absolutely willing to entertain, if perhaps not fully ready to endorse yet: that technology may be our best answer to the question of how we can reduce cost while preserving what we do that is unique and excellent in our universities.