HAVING PROVIDED WHAT I hope is a useful context, I will now discuss the prospects for using new technologies to address the productivity, cost, and affordability issues that I have described. I regard the prospects as promising, but also challenging. To succeed we will need to adopt a system-wide perspective, be relentless in seeking evidence about outcomes and costs, change some of our mindsets and our decision-making processes, and exhibit more patience than is our wont. None of these conditions is easy to satisfy! My focus will be on the contributions from established universities already serving large numbers of students. To be sure, we also want to serve new populations, at home and abroad, and a worldwide diffusion of knowledge is a most worthy goal—but it is not my central subject. Finally, in the search for new approaches, we need to recognize how well we do some things now, and how important it is that our educational institutions continue to stand for core values. That is the note on which I will end.

I am not a futurist but rather a maddeningly practical person who rarely has visions—and when I do, they are usually the result of having had a bad meal! But let me put such predilections to one side and ask readers to join me in imagining, just for a moment, how the intelligent harnessing of information technology through the medium of online learning might alter aspects of university life as we know it. Can we imagine a university in which

• faculty collaborate more on teaching (with technology serving as the forcing function)?

• faculty devote more of their time to promoting “active learning” by their students and are freed from much of the tedium of grading and even giving essentially the same lecture countless times?

• students receive more, and more timely, individualized feedback on assignments?

• instruction is guided by evidence drawn from massive amounts of data on how students learn, what mistakes students commonly make, and how misunderstandings underlying those mistakes can be corrected (“adaptive learning”)?

• technology is used to bring the perspectives of a more diverse student body onto its campus through its capacity to engage students from around the world?

• technology extends the educational process throughout one’s life through the educational equivalent of booster shots? And, ideally:

• a university in which institutional costs and tuition charges rise at a slower rate?

Before considering how nirvana might at least be approached (reaching nirvana will take a very long time, if indeed we can ever reach what has to be an ever-changing, ever-more ambitious goal), I want to describe briefly the evolution of my own thinking about technology and online learning. This story dates back at least as far as the Romanes Lecture that I gave at Oxford in 2000. In that lecture, I stressed the need to be realistic in thinking about how technology impacts costs, and I cited an early study from the University of Illinois that concluded: “Sound online instruction is likely to cost more than traditional instruction.”1 I then cited a supporting observation from another early study: “A cyberprofessor trades the ‘chains’ of lecturing in a classroom for a predictable number of hours at a specific time and place for the more unpredictable ‘freedom’ of being accessible by email and other cyber technologies.… Many cybercourse instructors find themselves being drawn into an endless time drain.”2 My conclusion at that time: “All the talk of using technology to ‘save money by increasing productivity’ has a hollow ring in the ears of the budget officer who has to pay for the salaries of a cadre of support staff, more and more equipment, and new software licenses—and who sees few offsetting savings.”3

I next added the not-so-profound thought that “this could change.” I am today a convert. I have come to believe that now is the time. Far greater access to the Internet, improvements in Internet speed, reductions in storage costs, the proliferation of increasingly sophisticated mobile devices, and other advances have combined with changing mindsets to suggest that online learning, in many of its manifestations, can lead to at least comparable learning outcomes relative to face-to-face instruction at lower cost. The phrase in many of its manifestations is important. Much confusion can result from failing to recognize that “online learning” is far from one thing—and that online learning is anything but static.4 It is, in fact, so many things and is evolving so rapidly that the efforts my colleague Kelly Lack and I made to create an understandable taxonomy did not succeed. We felt as if we were trying to “tether a broomstick,”5 and we decided to content ourselves with describing some distinguishing aspects of this complex landscape. (See the appendix at the end of this part.)

A far more sophisticated observer of digital trends than I am, President John Hennessy of Stanford, has been quoted as saying: “There’s a tsunami coming. [But] I can’t tell you exactly how it’s going to break.”6 Since I live on the East Coast, not the West Coast, I am even less capable of judging tsunamis, their shape, their force, or their timing, but I too am convinced that online learning could be truly transformative.

What needs to be done in order to translate could into will? The principal barriers to overcome can be grouped under three headings: the lack of hard evidence about both learning outcomes and potential cost savings; the lack of shared but customizable teaching and learning platforms (or tool kits); and the need for both new mindsets and fresh thinking about models of decision-making.7

Prominent leaders in higher education have made it abundantly clear that the faculty and leadership of many institutions, especially those regarded as trend-setters, will consider major changes in how they teach if, and only if, much more hard evidence about potential gains is available. To be sure, better “facts” will not suffice to bring about change, but evidence may well be a necessary if not a sufficient condition.

How effective has online learning been in improving (or at least maintaining) learning outcomes achieved by various populations of students in various settings? Unfortunately, no one really knows the answer to either this question or the important follow-on query about cost savings. There have been literally thousands of studies of online learning, and my colleague, Kelly Lack, has continued to catalogue them and summarize their findings.8 This has proved to be a daunting task—and, it has to be said, a discouraging one. Very few of these studies are relevant to the teaching of undergraduates, and the few that are relevant almost always suffer from serious methodological deficiencies.9 The most common problems are small sample size; inability to control for ubiquitous selection effects; and, on the cost side, the lack of good estimates of likely cost savings in steady state.

Ms. Lack and I originally thought that full responsibility for this state of affairs rested with those who conducted the studies. We have revised that judgment. A significant share of responsibility rests with those who have created and used the online pedagogies, since the content often does not lend itself to rigorous assessment, and offerings are rarely designed with evaluation in mind. Moreover, the gold-standard methodology—randomized trials—is both expensive and excruciatingly difficult to implement on university campuses. Also at play is what I can only call the missionary spirit. The creators of many online courses are true believers who simply want to get on with their work, without being distracted by the need to do careful assessments of outcomes or costs. In all fairness, I have to add that these are early days, and it is unrealistic to expect to have in hand today careful assessments of potentially path-breaking offerings such as some of the MOOCs (massive open online courses) that have been introduced relatively recently.10 Still, there is no excuse for not working now on plans for rigorous third-party evaluations.11

As Derek Bok has for years reminded everyone who will listen, the lack of careful studies of the learning effectiveness of various teaching methods is a long-standing problem; it predates and extends well beyond assessments of online learning. With typical candor, Professor William J. Baumol has observed: “In our teaching activity we proceed without really knowing what we are doing. I am teaching a course on innovative entrepreneurship, but I am doing so utterly without evidence as to the topics that should be emphasized, [or] the tools the students should learn to utilize. My state of mind on these matters is like that of 18th-century physicians, who used leeches and cupping to treat their patients simply because previous physicians had done so.”12

In an effort to fill part of this knowledge gap as it pertains to online learning, the ITHAKA organization mounted an empirical study of the learning outcomes associated with the use of a prototype statistics course developed by Carnegie Mellon University, taught in hybrid mode (with one face-to-face Q&A session a week).13 Carnegie Mellon’s course has several appealing features, including its use of cognitive tutors and feedback loops to guide students through instruction in basic concepts.14 In our study, we used a randomized trials approach, involving more than six hundred participants across six public university campuses, to compare the learning outcomes of students who took a hybrid-online version of this highly interactive course with the outcomes of students who took face-to-face counterpart courses. A rich array of data was collected at the State University of New York (SUNY), the City University of New York (CUNY), and the University System of Maryland. Although this study had limitations of its own, it is, we believe, the most rigorous assessment to date of the use of a sophisticated online course by the kinds of public universities that most desperately need to counteract the cost disease.15 I will cite only two principal findings about learning outcomes.

First, we found no statistically significant differences in standard measures of learning outcomes (pass or completion rates, scores on common final exam questions, and results of a national test of statistical literacy) between students in the traditional classes and students in the hybrid-online format classes (see figure 4).16 This finding, in and of itself, is not different from the results of many other studies. But it is important to emphasize that the relevant effect coefficients in this study have very small standard errors. One commentator, Michael S. McPherson, president of the Spencer Foundation, observed that what we have here are “quite precisely estimated zeros.” That is, if there had in fact been pronounced differences in outcomes between traditional-format and hybrid-format groups, it is highly likely that we would have found them.17

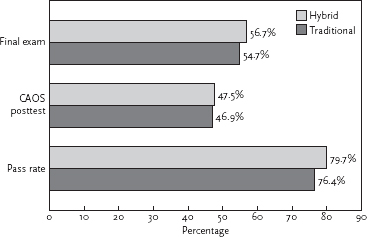

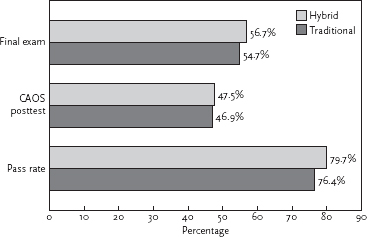

Figure 4 Effect of hybrid format on student learning outcomes

Note: None of the differences between traditional and hybrid courses was statistically significant at the 10 percent level.

Second, this finding is consistent not only across campuses, but also across subgroups of what was a very diverse student population. Half the students in our study came from families with incomes of less than $50,000, and half were first-generation college students. Fewer than half were white, and the group was about evenly divided between students with college GPAs above and below 3.0. The finding of consistent outcomes across this varied population rebuts the proposition that only exceptionally well-prepared, high-achieving students can succeed in online settings.18

Thus, while we did not find transformational improvements in learning outcomes, we did obtain compelling evidence that students with a wide range of characteristics learned just as much in the hybrid-online format as they would have had they instead taken the course in the traditional format.19 Students at the four-year universities in our study paid no price for taking a hybrid course in terms of pass rates or other learning outcomes. This seemingly bland result is, in fact, very important, in light of perhaps the most common reason given by faculty and deans for resisting the use of online instruction: “We worry that basic student learning outcomes will be hurt, and we won’t expose our students to this risk.” The ITHAKA research suggests that such worries may not be well founded—at least in situations akin to those we studied.

Several commentators on our study have expressed the hope—bordering on a conviction—that improvements in both the online offerings themselves and in the skill with which they are taught will lead, perhaps before long, to even better learning outcomes for such online offerings. The pace of change is dizzying, and improvements in pedagogy are almost certain to be made. In this regard, the pioneering work of the Khan Academy should be acknowledged. Salman Khan and his colleagues continue to learn a great deal about the most effective ways of using the online medium to teach.20 More generally, institutions and their faculty are likely to become increasingly adept at using the feedback and other features of sophisticated online courses. Thus, there is, I agree, reason to believe that the findings we have reported for learning outcomes are a kind of baseline. Future studies may well obtain evidence that is even more favorable to continued experimentation with online approaches. But that is in the future and is simply another reason for advocating both continued development of these pedagogies and rigorous testing of their effectiveness.

What about cost savings? Whether pedagogies such as the one we tested can in fact reduce instructional costs, thereby lowering the denominator of the productivity ratio, is an absolutely central question—which is given even more prominence by our finding of equivalent learning outcomes at even this early stage in the development of sophisticated online systems. Because of its clear importance, we thought hard about how to estimate potential cost savings. But, truth be told, we did not do nearly as well in looking at the “cost” blade of the scissors as we did in looking at learning outcomes. We were able to do no more than suggest a method of approach and hazard what are little more than rough guesses (speculations) as to the conceivable magnitude of potential savings in staffing costs.

A fundamental problem, cutting across all types of online offerings, is that contemporaneous comparisons of the costs of traditional modes of teaching and of newly instituted online pedagogies are nearly useless in projecting steady-state savings—or, worse yet, highly misleading. The reason is that the costs of doing almost anything for the first time are very different from the costs of doing the same thing numerous times. That admonition is especially true in the case of online learning. There are substantial start-up costs associated with course development that have to be considered in the short run but that are likely to decrease over time, as well as transition costs involved in moving from the traditional, mostly face-to-face, model to a hybrid model of the kind that we studied. Instructors need to be trained to take full advantage of automated systems with feedback loops. Also, there may well be contractual limits on section size that were designed with the traditional model in mind but that do not make sense for a hybrid model. Such constraints have to be accepted in the short term, even though it may be possible to modify them over time.21

To overcome (avoid!) these problems, we carried out simulated cost probes. We conceptualized the research question not as “How much will institutions save right now by shifting to hybrid learning?” but rather as “Under what assumptions will cost savings be realized, over time, by shifting to a hybrid format, and how large are those savings likely to be?”

The crude models we employed (which ignore entirely the “joint products” issue that grows out of the practice of supporting graduate students as teaching assistants) suggest savings in compensation costs alone ranging from 36 percent to 57 percent when the traditional teaching mode relies on multiple sections.22 Of course, this simulation underestimates substantially the potential savings from moving toward a hybrid model because it does not account for space costs, which, in many instances, can dominate cost calculations. A fuller analysis would also deal with other infrastructure costs, some of which would undoubtedly be higher in a hybrid format, as well as take into account reductions in the time costs incurred by students.23

Also highly relevant are the potentially profound effects of simplifications in scheduling and easier acceptance of transfer credits and evidence of prior learning. These could well lead, for many students, to an accelerated flow through the system, and thus to reduced time-to-degree and higher completion rates. If more students can be educated and if time-to-degree can be reduced, all without commensurate increases in costs, productivity could increase substantially via this avenue of impact.24 Careful modeling of new scheduling possibilities, and of the implications for time-to-degree and completion rates, is definitely in order.

ITHAKA’s empirical study is undoubtedly helpful in overcoming skepticism about the learning outcomes of online offerings, but we must remember that it involved only one course, in a field well suited to online learning, in predominantly on-site contexts. We need many more careful studies of varied approaches to online learning, carried out in a variety of settings (including two-year colleges as well as a variety of four-year institutions). It is encouraging that the MOOC provider edX, with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, is collaborating with two Boston-area community colleges to introduce an adapted version of an MIT online course in computer science (in what sounds like a hybrid mode).25 It will be interesting to see how successfully this MIT offering can be adapted to the needs of quite different student populations. Careful assessment of learning outcomes, preferably by a third party, would be instructive.

Nor is it sufficient simply to compare outcomes of particular online offerings with outcomes in traditional face-to-face courses. We also need studies that compare the effectiveness of different approaches to online learning. We elected to test the Carnegie Mellon course because we believed that the highly interactive character of the CMU course, informed by cognitive science, was more promising than simpler approaches. But this course was expensive to develop.26 Its value needs to be compared with the value of other approaches that are cheaper and less complex. It would also be highly desirable to compare outcomes and costs associated with various MOOCs against other approaches to online teaching. And we have to recognize that the answers to these questions about the costs and benefits of different approaches are likely to vary according to the content being presented, the student population, and the setting. ITHAKA, working with the MOOC provider Coursera and others, is engaged in just such a cross-platform study in collaboration with the University System of Maryland.27

Designing research strategies in this area is a complicated business under the best of circumstances. Randomized trials are, it is generally agreed, the most promising way of reducing the ever-present risk of selection bias, but a huge takeaway from our empirical research using this methodology is that it is expensive and devilishly difficult to carry out. As we learned painfully, there are many important details that have to be worked out: how best to describe the course to be tested, how to recruit student participants in the study (including what incentives to use), how to randomize apprehensive students between “treatment” and “control” groups (and how to be sure that they stay in their assigned group), how to collect background information about student participants, and how to satisfy institutional review board (IRB) requirements in a timely way. Moreover, finding good answers requires the dayto-day involvement of campus staff not directly responsible to outsiders like us.28 Looking ahead, I now think—heresy of heresies!—that the case for using randomized trials should itself be subject to careful cost-benefit analysis.29 Appealing as they are, this may be an instance in which, in at least some cases, “the best is the enemy of the good.”30

Last on my short list of research priorities is the evident need for creative analyses on the cost side of the ledger. This work should do more than just project direct costs (on a forward-looking, steady-state basis). It should include an analysis of implications for space utilization, capital costs, and indirect costs, hard as these are to estimate. It should also consider freshly the many ways in which online technologies may influence the way sizeable parts of the curriculum can be re-engineered (bearing in mind the injunction of the authors of the New England Journal of Medicine article about the need for such re-engineering, as in the much earlier introduction of electricity to manufacturing).31 The pace at which current students get through the educational system is enormously important, as are completion rates. It may be possible to utilize online technologies to allow energetic secondary school students to get an early start on their college education—perhaps by preparing them to take college-level tests that will allow them to place out of some introductory courses. Alternatively, given that the out-of-pocket costs of enrollment, and of attrition, are relatively low compared to the costs of traditional courses for which students need to pay tuition, MOOCs could allow students to experiment with different classes and get a sense of what disciplines interest them before they ever set foot on campus.32

The biggest opportunity for MOOCs to raise productivity system-wide, and to lower costs, may well lie in finding effective ways for third parties to certify the “credit-worthiness” of their courses—and the success of students in passing them. The American Council on Education and Coursera have announced a pilot project that will entail faculty-led assessments of a subset of Coursera offerings. Students who complete courses that satisfy the requirements of the ACE’s standard College Credit Recommendation Service, and who pass an identity-verified exam, will be able to have a transcript submitted to the college of their choice. It will then be up to individual colleges to decide whether to give transfer credit for such work, though at present more than two thousand colleges and universities across the country generally accept ACE credit recommendations.33 One key question to be addressed by colleges contemplating accepting such credentials will be how to define the coherence of the totality of the coursework that they expect students to complete in order to receive one of their degrees.

I now move on to discuss another type of need if we are to make real progress in utilizing technology in the pursuit of our aspirations. A major conclusion of ITHAKA’s Barriers to Adoption report is that “perhaps the largest obstacle to widespread adoption of ILO [interactive learning online]–style courses” is the lack at the present time of a “sustainable platform that allows interested faculty either to create a fully interactive, machine-guided learning environment, or to customize a course that has been created by someone else (and thus claim it as their own).” A companion conclusion is that “faculty are extremely reluctant to teach courses that they do not ‘own.’”34 As one commentator cited in the Barriers report put it, “No one wants to give someone else’s speech” (even though all of us are happy to borrow felicitous phrases). This is by no means just about ego, although ego is certainly involved. Faculty may understandably feel that they are not sufficiently familiar with content prepared solely by someone else to teach it effectively. Also, both the structure of content and examples often need to be tailored to a particular student audience.35

It would be easy—but incorrect—to infer from this line of argument, which emphasizes the need for customization, that the development of online courses has to be a responsibility of each individual campus. Sole reliance on purely homegrown approaches would be foolishly inefficient and simply would not work in most settings. It would not take advantage of the economies of scale offered by sophisticated software that incorporates features of well-developed platforms, including elaborate feedback loops and instructive peer-to-peer interactions.36 Furthermore, many institutions simply do not have the money or the in-house talent to start from scratch in creating sophisticated online learning systems that can be disseminated widely. Nor would it make sense to re-invent wheels that can be readily shared.

There is clearly a system-wide need for sophisticated, customizable platforms (or tool kits) that can be made widely available, maintained, upgraded, and sustained in a cost-effective manner. Yet higher education thus far has failed to find a convincing solution to this problem, and immediate prospects for a solution are uncertain at best. In seeking to address this need, we must recognize the high probability that quite different pedagogies—and therefore somewhat different platforms—will be appropriate in subjects in which there are concrete concepts to be mastered and one right answer to many questions (for example, basic statistics)—as contrasted with discursive subjects which benefit from the exchange of different points of view (e.g., the Arab-Israeli conflict). At one point, I was much more inclined than I am at present to believe that a single platform or single tool kit might be appropriate. It now seems clear to me that the notion of a single dominant platform is unrealistic, given the entrepreneurial inclinations of numerous individuals and organizations. I now believe that such a notion is also unwise. There is much to be said for experimentation with different models and for competition among models as we search for approaches well suited to different needs. Adoption of any specific platform or platforms should be driven by a compelling strategy.

How should such platforms be developed? A strong prima facie case can be made for a high-level, collaborative effort within the traditional higher education community; after all, collaborations have been highly beneficial in sharing other assets, such as ultra-expensive scientific equipment. It is, however, widely recognized that collaborative efforts are difficult to organize, especially when much nimbleness is needed.37 Collective decision-making is often cumbersome, and it can be hard to avoid lowest-common-denominator thinking. My favorite example is the Peace of Paris negotiations at the end of World War I, which ended so disastrously. John Maynard Keynes’s famous account of the collective efforts of the participants is worth recalling: “These then were the personalities of Paris—I forbear to mention other nations or lesser men: Clemenceau, aesthetically the noblest; the President, morally the most admirable; Lloyd George, intellectually the subtlest. Out of their disparities and weaknesses the Treaty was born, child of the least worthy attributes of each of its parents, without nobility, without morality, without intellect.”38

There is, then, much to be said for seeking leadership from individual entities that are well-respected and have demonstrated a capacity to execute. Early on in our thinking about this issue, my colleagues and I were wondering whether Carnegie Mellon might address this need by scaling up the promising, highly interactive system that we tested and correcting the main shortcomings noted by participants in our study, including their interest in having a more customizable platform. Carnegie Mellon has expressed a commitment to developing the tools that are needed for authoring and analytics, which could well improve the scalability of their platform as we had originally hoped, but such an outcome is likely to be at least a year away.39 In a field that is evolving as rapidly as this one, it remains to be seen how CMU’s cognitive-science, adaptive-learning approach will fit into the online learning landscape over the next few years.

We could, of course, simply let the marketplace provide: it is possible that for-profit entities, trading on financial incentives, might develop one or more effective platforms. There is, however, a risk that a for-profit might elect to cover some or all of its costs by essentially privatizing the significant amounts of information that such online systems can generate about how students learn. The example of Google illustrates dramatically the value that can be derived from exploiting a proprietary database for purposes such as selling targeted advertising. Massive amounts of data on how students learn can further the core mission of not-for-profit higher education and lead, in time, to the creation of better adaptive-learning systems. It would be unfortunate if the potential “public good” benefits of the rich information generated by online learning systems were lost. The educational community writ large should think hard about whether, and if so how, a depository for such information could be created and maintained. Such a depository should probably be created under the auspices of a nonprofit entity that recognizes explicitly the value of broad access to such critically important data. We should not think, however, that nonprofits are immune from the temptation to privatize and control data. There are too many examples, in publishing and in other fields, of situations in which nonprofits act very much like their for-profit cousins.

I have left for last what I regard as the most promising (though still entirely speculative) option at present: namely, the possibility that leading MOOCs might meet the need for readily adaptable platforms or tool kits. The developers of Coursera, edX, and Stanford’s Class2Go platform have said that they are committed to developing systems that can be used widely by others.40 No one should doubt the good intentions of such entities. Nor should anyone undervalue the substantial resources at their disposal. It is precisely because they have a rare combination of assets—impressive technical capacity, a strong financial base, and real standing in the academic community (enhanced by extraordinary media coverage)—that I regard them, at least right now, as the highest-potential game in town. But neither should anyone underestimate the difficulty of modifying MOOCs originally designed to provide direct instruction to many thousands of individual students worldwide so that they can also serve the needs of existing educational institutions that serve defined student populations.41

The interviews we did for our Barriers study revealed “little enthusiasm for prepackaged online courses that did not permit customization, regardless of the institution ‘sponsoring’ the course, its quality, or the degree of interactivity.”42 And there is something of an inherent conflict, or at least a tension, between, on the one hand, the structure of MOOC offerings, which are designed largely by renowned and high-visibility professors at leading universities and which are generally provided worldwide on an “as-is” basis and, on the other hand, the need for at least some campus-specific customization. A related point is that the cost-effectiveness of MOOCs in their “direct to student” mode stems largely from the fact that their one-size-fits-all structure drives the marginal cost of serving even an extra thousand students close to zero. It is much less obvious how—or even whether—large cost savings can be achieved when a MOOC has to be customized for local use by a particular institution with a much smaller student population and a resident teaching staff. In addition, there are complex intellectual property rights issues that need to be resolved.43

We should also recognize that while there has been much discussion about potential sources of revenue for MOOCs (charging for certificates of completion, becoming a kind of job-placement enterprise, and so on), the viability of the various hypothetical possibilities remains to be demonstrated.44 A major lesson from the earlier MIT OpenCourseWare (OCW) experience is that it can be much easier to create something like OCW, often with philanthropic support, than to find regular sources of revenue to pay the ongoing costs of maintaining and upgrading the system. MIT is today still paying the running costs of OCW each year, and we are told that the faculty and trustees of MIT are convinced that they cannot go down the same path again—their pride in OCW as a truly pioneering venture notwithstanding.45 Donor fatigue is a fact of life, and some regular, predictable source of revenue is needed for sustainability. There is real danger in announcing that something is free without knowing who is to pay the ongoing costs, which are all too real and cannot be ignored.46 The “no free lunch” adage comes to mind.

These cautions and open questions about MOOCs cannot be ignored or assumed away. Nonetheless, I believe that the educational community should make every effort to take advantage of the great strengths of the leading MOOCs. Not only should we encourage their continuing interest in serving existing institutions as well as a global audience of individuals, but we should also try to find ways of testing learning outcomes and assessing cost-saving options for specific universities and university systems. It seems clear that MOOCs have an extraordinary capacity to improve access to educational materials from renowned instructors in various subjects for learners throughout the world. However, as far as I am aware, right now there is no compelling evidence as to how well MOOCs can produce good learning outcomes for 18- to 22-year-olds of various backgrounds studying on mainline campuses—and this is an enormous gap in our knowledge.

There is good reason to be extremely cautious in extrapolating crude findings for the student population that took the first MOOCs to mainline student populations. A highly preliminary study of the demographics of a MOOC in circuits and electronics, which at the time was offered by MITx but which is now offered by the larger edX organization, found that those students still around at the end of the course bore almost no resemblance to the students on mainline campuses in this country. One dramatic statistic: four out of five students who completed that MOOC had taken a comparable course at a traditional university prior to working their way through the MITx course. The circuits and electronics MOOC completers also differed along many other dimensions from traditional on-campus populations.47

In addition to pursuing aggressively these key questions concerning learning outcomes on mainline campuses, the entire higher education community has an interest in thinking about business models that would assure the sustainability of the most promising MOOCs without compromising educational goals.48 The experiences of entities such as JSTOR in developing sustainable business models could be relevant. Indeed, I suspect that at least part of the answer to the sustainability issue could lie in finding a JSTOR-like mechanism for charging reasonable fees to institutions (and/or students) that realize cost-saving benefits from MOOCs. Coursera and Antioch University have reached a content-licensing agreement that seems to move at least some distance in this direction.49

My last category of challenges to be addressed is something of a grab bag—but a useful one, I hope. Many of the specific issues mentioned in the Barriers report share the attribute of requiring strong institutional leadership and even fresh ways of thinking about decision-making. These include, for example, the fact that “online instruction is alien to most faculty and calls into question the very reason that many pursued an academic career in the first place.… they had enjoyed being students, and valued the relationships that they enjoyed with their professors.”50 Other barriers include the fear that online instruction will be used to diminish faculty ranks and the failure to provide the right incentives for faculty who are asked to lead online initiatives.

Hard as it sometimes is for beleaguered deans and presidents to confront challenges of these kinds directly, it is rarely wise to gloss over the most sensitive issues. I am convinced that a new, tougher, mindset is a prerequisite to progress. There is too strong a tendency to respond to financial pressures by economizing around the edges and putting off bigger—and harder—choices in the hope that the sun will shine tomorrow (even if the forecast is for rain!).

The seemingly unrelenting upward spiral of costs and tuition charges can be arrested, at least in some degree, only if presidents, provosts, and trustees make controlling both costs and tuition increases a priority. Academic leaders must look explicitly for strategies to lower costs. I am not saying that educational leaders lack courage (though, sadly, some do). The reality is that controlling costs is a hard sell, in part because strong forces are pushing in the opposite direction. As one of our advisers said, “Those opposed have so many ways of throwing sand in the wheels.”51

I continue to believe that the potential for online learning to help reduce costs without adversely affecting educational outcomes is very real. Absent strong leadership, however, there is a high probability that any productivity gains from online education will be used to gild the educational/research lily—as has been the norm for the last twenty years. Presidents and provosts should not mince words in charging their deans and faculty with teaching courses of comparable or superior quality with fewer resources—thereby either lowering the denominator of the productivity ratio or raising the student-learning component of the numerator (or both).52

There is a definite political aspect to all of this. We must recognize that if higher education does not begin to slow the rate of increase in college costs, our nation’s higher education system will lose the public support on which it so heavily depends. There has been an undeniable erosion of public trust in the capacity of higher education to operate more efficiently.53 In this respect, the better-off private and public universities—which rely heavily on many forms of federal support, including direct research grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, and other federal agencies; indirect cost recovery; financing of graduate students; and student loan guarantees—are in much the same boat as the more obviously endangered parts of the educational system. Efforts to save resources should be highly visible. Those who are skeptical about the capacity of established institutions to take positive steps in this sensitive area need to be given evidence that change is possible.

One favorable omen is the openness of many faculty to new ways of thinking—including the desirability of “flipping the classroom.”54 A recent survey shows that a “decisive majority of professors”—69 percent—view with more excitement than fear the prospect of “changing the faculty role to spend less time lecturing and more time coaching students.”55 Movement away from reliance on traditional lecturing, especially in large introductory courses, should allow institutions to devote the valuable in-person time of both faculty and students to activities that are more powerfully educational. Flipping the classroom need not save resources, however, and can even lead to higher costs. Lecturing is highly cost-efficient, whatever its educational shortcomings. Institutions that decide to flip the classroom should be well aware of this fact and should see if there are ways of saving resources by reducing the total amount of time spent in small group sessions (while, one would hope, improving the quality of the time that is spent). The hybrid version of the Carnegie Mellon statistics course that we tested is one possible model.

Growing openness to such concepts does not translate automatically, however, into new modes of teaching. Required is a willingness to question established norms, including models of decision-making. The challenges are at least as much conceptual, organizational, and administrative as they are technical. I wonder if the particular models of what is often called “shared governance” that have been developed over the last century are well suited to the digital world. Shared governance can mean dividing up tasks in seemingly clear-cut ways: leaving “corporate” decisions of one kind or another entirely in the hands of trustees and “academic” decisions entirely in the hands of faculty.56 But if wise decisions are to be made in key areas, such as teaching methods, it is imperative that they be made by a mix of individuals from different parts of the institution—including faculty leaders but also others well-positioned to consider the full ramifications of the choices before them. There are real dangers in relying on the compartmentalized thinking that too often accompanies decentralized modes of organization to which we have become accustomed.57

Given the institution-wide stakes associated with judgments as to when and how digital technologies should be used to teach some kinds of content, there is a strong case to be made for genuinely collaborative decision-making that includes faculty, of course, but that does not give full authority to determine teaching methods to particular professors or even to particular departments. There are too many spillover effects. It is by no means obvious that resources saved by using machine-guided learning in large introductory courses in subjects especially well suited to this approach should be captured in their entirety by the departments concerned.58 It is important to think in terms of the institution as a whole in allocating savings—with prospective students and their parents among the stakeholders who deserve consideration. Also, the investments required to allow such savings—and to sustain initiatives—can be considerable and often have to be approved by a central authority.

Specific organizational solutions will vary from institution to institution, but the general principle is clear: some centralized calibration of both benefits and costs is essential. In a less complex age, it may have been sensible to leave almost all decisions concerning not just what to teach but how to teach in the hands of individual faculty members. It is by no means clear, however, that this model is the right one going forward, and it would be highly desirable if the academic community were seized of this issue and addressed it before “outsiders” dictate their own solutions. To repeat: faculty involvement is essential. There is a self-evident need for consultation with those who are expert in their disciplines and experienced in teaching—but this is not the same thing as giving faculty veto power over change.

Nor is this, I would emphasize, an issue of academic freedom, as that crucially important concept is properly understood. Faculty members should certainly be entirely free to speak their minds, as scholars and as teachers. But this freedom of expression should not imply unilateral control over methods of teaching. There is nothing in the basic documents explaining academic freedom to suggest that such control is included. It is not.59 If academic freedom is construed to mean that faculty can do anything they choose, it becomes both meaningless and indefensible.60

The case for genuinely fresh thinking about decision-making and shared governance rests only in part on the need for institutions to make carefully considered decisions about teaching methods in specific situations. It is also based on the fundamental nature of digital technologies, and the changes in the storage and dissemination of information, that are everywhere evident. One does not have to believe—as I certainly do not—that methods of online teaching, including MOOCs, will lead to diminished interest in high-quality residential education to recognize that the broader structure of higher education is likely to change quite profoundly. What we are witnessing is the early stage of at least a partial unbundling of activities that used to be the responsibility of a single faculty member or of groups of faculty in a single campus location: creating knowledge, teaching content, testing students’ grasp of that content, and credentialing.61 Joseph Aoun, president of Northeastern University, describes this as a “vertically integrated model,” and he contrasts it with the rise of “horizontal” models in which different people may perform some of these core functions—and perform them in different locations and for much larger numbers of students.62

In the more horizontal model that Aoun and others envision, the roles of some faculty may be quite different than they are today. Different mixes of talents and inclinations will be required, and the organizational and administrative questions will be challenging. Some people and some institutions will undoubtedly resist such changes—some wisely, some unwisely. The New York University professor and writer Clay Shirky compares what is going on in some parts of education today with what happened to the recording industry when large numbers of people started to listen to MP3s. He describes this pattern as “a new story rearranging people’s sense of the possible, with the incumbents the last to know.… First, the people running the old system don’t notice the change. When they do, they assume it’s minor. Then that it’s a niche. Then a fad. And by the time they understand that the world has actually changed, they’ve squandered most of the time that they had to adapt.”63

No one can say confidently how powerful or how pervasive the horizontal model will turn out to be—how many colleges and universities will be affected, and in what ways. But it seems clear that all of us interested in the future of colleges and universities, and in preserving key roles for faculty, are well advised to do our best to get some distance “ahead of the wave” (to return to John Hennessy’s tsunami metaphor).64 It is an open question how the structure of decision-making and the definition of shared governance need to be modified in light of these changes brought on by the still rapidly evolving Internet age.65 And it is a question that those of us in the academy, or with close ties to it, should be pondering now, before more time elapses.

Let me now circle back to what I said earlier. As we contemplate a rapidly evolving world in which greater and greater use will surely be made of online modes of teaching, I am convinced that there are central aspects of life on our traditional campuses that must not only be retained but even strengthened. I will mention three.

First is the need to emphasize—and, if need be, to re-emphasize—the great value of “minds rubbing against minds.” We should resist efforts to overdo online instruction, important as it can be. There are, of course, both economic constraints and practical limitations on how much education can be delivered in person. But those of us who have benefited from personal interactions with brilliant teachers (some of whom became close friends), as I certainly have, can testify to the inspirational, life-changing aspects of such experiences. The half-life of content taught in a course can be short, as we all know; but great teachers change the way their students see the world (and themselves) long after the students have forgotten formulas, theorems, and even engaging illustrations of this or that proposition.66 Moreover, a great advantage of residential institutions is that genuine learning occurs more or less continually, and as often, or more often, out of the classroom as in it. This cliché, repeated by countless presidents and deans, conveys real truth. Late-night peer-to-peer exchanges offer students hard-to-replicate access to the perspectives of other people. As one of my greatest teachers, Jacob Viner, never tired of warning his students, “There is no limit to the amount of nonsense you can think, if you think too long alone.”

My plea is for the adoption of a portfolio approach to curricular development that provides a carefully calibrated mix of instructional styles. This mix will vary by institutional type, and relatively wealthy liberal arts colleges and selective universities can be expected to offer more in-person teaching than can many less privileged institutions. However, even the wealthiest, most elite colleges and universities that seemingly can afford to stay pretty much as they are, at least in the short run, should ask if failing to participate in the evolution of online learning models is to their advantage, or even realistic, in the long run.67 Their students, along with others of their generation, will expect to use digital resources—and to be trained in their use. And as technologies grow increasingly sophisticated, and we learn more about how students learn and what pedagogical methods work best in various fields, even top-tier institutions will stand to gain from the use of such technologies to improve student learning.

Second, we must retain, whatever the provocations, the unswerving commitment of great colleges and universities to freedom of thought—as exemplified so clearly by my great friend of so many years, Richard Lyman, Stanford’s seventh president, who died in May of this year. President Lyman stood resolutely for civility and protection of the rights of all. When he was compelled to summon the police to curb an over-the-edge demonstration in 1969, his action was applauded by some, but he thought the applause was misplaced. President Lyman said: “Anytime it becomes necessary for a university to summon the police, a defeat has taken place. The victory we seek at Stanford is not like a military victory; it is a victory of reason and the examined life over unreason and the tyranny of coercion.”68

Third, our colleges and universities should focus unashamedly on values as well as on knowledge—and we should spend more time than we usually do considering how best to do this.69 This is most definitely not a plea for pontificating. When President Robert Hutchins was urged to teach his students at Chicago to do this, that, or the other thing, he demurred, explaining: “All attempts to teach character directly will fail. They degenerate into vague exhortations to be good which leave the bored listener with a desire to commit outrages which would otherwise have never occurred to him.”70

Let me now refer to a baccalaureate address given at Princeton in 2010 by Jeff Bezos, the CEO of Amazon, titled “We Are What We Choose.”71 Bezos began by reciting a poignant story of a trip he took with his grandparents when he was ten years old. While riding in their Airstream trailer, this precocious ten-year old laboriously calculated the damage to her health that his grandmother was doing by smoking. His conclusion was that, at two minutes per puff, she was taking nine years off her life. When he proudly told her of his finding, she burst into tears. His grandfather stopped the car and gently said to the young Bezos: “One day you’ll understand that it’s harder to be kind than clever.” Bezos went on in his address to talk about the difference between gifts and choices. “Cleverness,” he said, “is a gift, kindness is a choice. Gifts are easy—they’re given, after all. Choices can be hard.” Colleges and universities can, and should, find ways to help their students learn this key distinction—and encourage them, at least some of the time, to choose kindness over cleverness.

I return, finally (which one of my friends called the most beautiful word in the English language), to the question posed at the outset of this book: is online learning a fix for the cost disease? My answer: no, not by itself. But it can be part of an answer. It is certainly no panacea for this country’s deep-seated educational problems, which are rooted in social issues, fiscal dilemmas, and national priorities, as well as historical practices. In the case of a topic as active as online learning, we should expect inflated claims of spectacular successes—and of blatant failures. The findings I have reported warn strongly against too much hype. What Kin Hubbard famously said about those who claim certain knowledge of the currency question can be applied to online learning: “Only one fellow in ten thousand understands the currency question, and we meet him every day.” There is a real danger that the media frenzy associated with MOOCs will lead some colleges and universities (and, especially, business-oriented members of their boards) to embrace too tightly the MOOC approach before it is adequately tested and found to be both sustainable and capable of delivering good learning outcomes for all kinds of students.72

Uncertainties notwithstanding, it is clear to me that online systems have great potential. Vigorous efforts should be made to explore further uses of both the relatively simple systems that are proliferating all around us, often to good effect, and more sophisticated systems that are still in their infancy—systems sure to improve over time, perhaps dramatically. In these explorations, I would urge us not to hesitate to experiment, but always to insist on assessments of outcomes. I would also urge us to think in terms of system-wide approaches and to exercise that rarest of virtues, patience. The careful development (and testing) of promising new pedagogies can take years and even decades.73

I will end with a last story, on this theme of patience. It comes from the Arabian Nights, and I owe it to a very wise man, Ezra Zilkha, who was born in Baghdad. This is the story of the black horse. A prisoner who was about to be executed was having his last audience with the sultan. He implored the sultan: “If you will spare me for one year, I will teach your favorite black horse to talk.” The sultan agreed immediately with this request, and the prisoner was returned to his quarters. When his fellow prisoners heard what had happened, they mocked him: “How can you possibly teach a horse to talk? Absurd.” He replied: “Wait a minute. Think. A year is a long time. In a year, I could die naturally, the sultan could die, the horse could die, or, who knows, I might teach the black horse to talk.” The lesson of the story, Mr. Zilkha said, is, “If you don’t have an immediate answer, buy time. Time, if we use it, might make us adapt and maybe, who knows, find solutions.” If speaking to a college or university audience such as this one, Mr. Zilkha would add: “It is the job of the Stanfords of this world to teach the black horse to talk.”

At one end of this highly variegated landscape is an extremely large number of relatively straightforward online courses that provide an assortment of instructional materials on the web, often including videos, practice problems, and homework assignments. These courses (and some entire degree programs based on them) are usually institution-specific and built on learning management systems; they can be aimed at students in residence, distance learning populations, or both. They usually carry credit and are offered by both for-profit universities such as the University of Phoenix and a wide variety of nonprofit educational institutions. Some such courses in the nonprofit sector—not all of them entirely or even mostly online—have been created with the assistance of the National Center for Academic Transformation (NCAT) through its course-redesign initiative, which itself involves different models of online instruction.74

According to a January 2013 report by the Babson Survey Research Group, the Sloan Consortium, and Pearson, about one in three college students now takes at least one online course (compared with about one in ten in fall 2002, the first year the survey was administered), and whereas total enrollments in higher education declined between fall 2010 and fall 2011, online enrollments grew about 9 percent during that time period.75 Indeed, the current spread of online offerings is dizzying. During one week in August 2012, I came across announcements of online initiatives by the University of Florida system, a Seminole tribe program also in Florida (the Native Learning Center), University of Kansas, Utah Valley University, and a number of HBCUs whose activities were reported by the Digital Learning Lab of Howard University. (Websites are the best way to learn about these, and other initiatives too numerous even to mention here.) In addition, there are many online courses overseas, and the Open University in the United Kingdom has been especially active in this field for years.76 In September 2012, Indiana University announced IU Online, a major new initiative that builds on a long history of work at that university and illustrates what is happening at a variety of institutions throughout the country.77

The proliferation of offerings called online surely qualifies as a tidal wave, if not yet a tsunami. In addition to courses that can be counted, all of us feel the pervasiveness of the Internet in higher education by the increasing use of it in standard course-management systems, virtual reading materials, and a rapidly proliferating number of more and more sophisticated electronic textbooks incorporated into the curriculum. Even courses that are called “traditional” almost always involve some use of digital resources.

Carnegie Mellon University deserves special mention as a pioneer in the development of highly interactive online courses that have been built by teams of cognitive scientists, software engineers, and disciplinary specialists under the leadership of Candace Thille’s Open Learning Initiative. These OLI courses feature cognitive tutors—which draw on principles from cognitive psychology to guide a student through learning activities, taking into account the student’s progress—and three types of feedback loops: system to student, providing instant feedback to students on their answers to problems and carefully structured hints as to how to get the right answers; system to teacher, providing current information to the teacher on how individual students, as well as students in general, are doing (thereby enabling teachers to make more effective use of any face-to-face time that is available); and system to course designer, providing information on parts of the course that are working well and parts that need improvement.78

At still another corner of this landscape are the MOOCs (massive open online courses)—usually designed by highly regarded professionals and taught to thousands of students worldwide by well-known professors. Typically, students who have registered for these courses (usually for free) watch videos and complete assignments that are machine-graded or graded by other students and/or teaching assistants. With very few exceptions, these courses do not carry college credit or lead to degrees, and they may or may not lead to certificates of accomplishment or badges (for which students may need to pay a modest fee) that indicate mastery of particular skills. Three of the best-known exemplars of MOOCs are listed below:

• Coursera, a for-profit spin-off from Stanford that offers a wide variety of courses in close collaboration with several dozen high-profile universities (including Princeton, the University of Toronto, and the University of Michigan, as well as Stanford), to which Coursera provides authoring tools and other forms of assistance;

• Udacity, another for-profit Stanford spin-off, which concentrates on computer science and related fields; unlike Coursera, Udacity works only with individual professors (rather than through institutions);

• edX, a nonprofit partnership of MIT, Harvard, the University of California at Berkeley, Georgetown, Wellesley, and the University of Texas System that offers courses of its own, initially focusing mainly on computer science and engineering, and which also plans to make its platform available on an open-source basis to faculty elsewhere who wish to create their own courses.79

Again, websites are the best source of information about these and other MOOCs.

Another well-known provider of free online course materials is Khan Academy, a nonprofit organization which is perhaps best known for its short instructional videos hosted on YouTube, but which today emphasizes automated practice exercises that are used heavily by secondary school students. Its instructional videos cover a broad range of disciplines, ranging from civics and art history to computer science, chemistry, differential equations, and the Greek debt crisis, though it has generally been Khan’s mathematics materials that are used in classroom settings. While one can argue about whether Khan Academy should be classified as a MOOC, in light of the fact that its typical offerings are not courses, the breadth and widespread appeal of the Khan Academy’s offerings undoubtedly bear mention.

In mid-November 2012, a consortium of ten prominent universities announced that it will offer credit-bearing online courses, starting in fall 2013, as part of an initiative called Semester Online.80 The consortium will operate through the platform developed by the educational technology company 2U. Both students enrolled in the member institutions and students outside those institutions will be able to take the thirty or so courses offered by the consortium members for credit, though students outside the host universities will have to apply to take the courses and, if admitted, pay tuition for those courses. Unlike MOOC providers, this consortium will emphasize small, live “virtual” discussion groups in which students interact with each other and with the instructor in real time. The small class sizes and synchronous nature of the interactions are likely to make these offerings more expensive than MOOCs and some other online courses.

In contemplating the wide array of offerings that populate the online universe, it may be helpful to think in terms of eleven overlapping distinctions, grouped under four headings.

1. How advanced is the content of the course, and are there daunting prerequisites?

2. To what extent does the course contain cognitive tutors (akin to those available in Carnegie Mellon’s OLI courses) or other adaptive learning features?

3. To what extent does the course allow learners to interact with each other, and perhaps with instructors or teaching assistants who are leading or overseeing the course (if there are any)?

4. Is the course purely online, or is it a hybrid course with a face-to-face element?

5. Is the online component of the course offered in synchronous mode (that is, do students all have to be online at the same, specified times), or in asynchronous mode (where students can access the materials any time they choose), or both?

6. Is the course offered “direct to student” or through an existing college or university?

7. What is the primary intended student population—working adults in the United States (who more often than not study part-time), more traditional students (often but not always campus-based), or anyone and everyone with aptitude and interest all over the world?

8. To what extent can the course be adapted, or re-purposed, to serve other sets of students in the future, in various settings? There are important distinctions among online courses that are “home-grown,” designed on an institution-specific platform that has little customization capacity, and intended specifically for use by a known institutional population; online courses that are developed for a broader (and unknown) population of students; and online courses that are developed alongside, or on top of, a general platform but that have customizable features and allow for “local” varieties targeted at particular populations.

9. Does the course offer credit and a path to a degree, a certificate of accomplishment, or no credit or assessment of accomplishment?

10. Who owns (and/or has license to use) the intellectual property of the course materials? Is the controlling entity a for-profit or nonprofit organization?

11. What is the business model underlying the course offering? Is the course available to students for free, and if it is, who pays for the development and ongoing operation of the course?

There are obviously hundreds of possible permutations and combinations involving these and other distinctions. With so many dimensions along which online courses can be classified, a simple taxonomy can be both elusive and more confusing than helpful. The variety of online offerings is often under-appreciated, as is the importance of deciding what characteristics are appropriate in a particular setting.

1. William G. Bowen, At a Slight Angle to the Universe: The University in a Digitized, Commercialized Age, Romanes Lecture for 2000, University of Oxford, October 17, 2000 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001), 24 (also available online at www.mellon.org/internet/news_publications/publications/romanes.pdf); “Teaching at an Internet Distance,” University of Illinois faculty seminar, December 7, 1999, www.vpaa.uillinois.edu/tid/report.

2. Cited in Bowen, At a Slight Angle to the Universe, 23–24; Peter Navarro, “Economics in the Cyberclassroom,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14, no. 2 (Spring 2000): 129.

3. See Bowen, At a Slight Angle to the Universe, 24.

4. In the words of the authors of one study comparing face-to-face instruction with three different varieties of distance learning: “Like Campbell’s Soups, distance learning now comes in so many varieties that it is increasingly difficult to generalize about it.” (James V. Koch and Alice McAdory, “Still No Significant Difference? The Impact of Distance Learning on Student Success in Undergraduate Managerial Economics,” Journal of Economics and Finance Education 11, no. 1 (Summer 2012): 36.)

5. This imagery is from Keynes’s explanation of his difficulty rendering a portrait of Lloyd George at the Peace of Paris. John Maynard Keynes, Essays in Biography (New York: Horizon Press, 1951), 33. I shall offer one other snippet from this remarkable essay when I discuss collective decision-making.

6. “Changing the Economics of Education,” interview with John Hennessy and Salman Khan, Wall Street Journal, June 4, 2012. See also Ken Auletta, “Get Rich U,” New Yorker, April 30, 2012; Billy Gallagher, “Q&A: President John Hennessy on Online Education,” Stanford Daily, October 30, 2012.

7. For a fuller study of barriers to adoption of online pedagogies, see Lawrence S. Bacow, William G. Bowen, Kevin M. Guthrie, Kelly A. Lack, and Matthew P. Long, Barriers to Adoption of Online Learning Systems in U.S. Higher Education, May 1, 2012, available on the ITHAKA website at www.sr.ithaka.org. The discussion in this book draws heavily on this report but is more cryptic and organizes the issues differently.

8. Kelly A. Lack, “Current Status of Research on Online Learning in Postsecondary Education.” This is a revised version of a paper originally dated May 18, 2012, available at www.sr.ithaka.org/research-publications/current-status-research-online-learning-postsecondary-education.

9. In the widely cited SRI/DOE meta-analysis (usually cited as Means et al., 2009), most of the forty-six studies reviewed involved online learning in the fields of medicine or health care, and a great many studies compared the use of the two different modes of learning for less than a full semester. In addition, only twenty-five of the fifty-one online versus face-to-face comparisons analyzed in the meta-analysis involved undergraduate students. (The other twenty-six involved students in grades K–12, graduate students, or other types of learners.) See Barbara Means et al., Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, 2009), www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/tech/evidence-based-practices/finalreport.pdf.

10. In general, MOOCs are free or low-cost online courses that are available to interested users—in some cases, by the thousands, tens of thousands, or hundreds of thousands—throughout the world. These courses typically consist of video lectures by well-known professors or experts in a particular field, often affiliated with elite institutions; the video lectures generally are complemented by problem sets and/or other assignments, and, in some cases, discussion boards where students can interact with one another asynchronously. Students typically have very little opportunity to interact with professors (with the exception, in some cases, of mass e-mails sent by the instructor to all enrolled students), though some instructors have teaching assistants available to answer questions or monitor the discussion boards. Completion of a MOOC is sometimes recognized with a certificate of accomplishment from the professor or from the MOOC itself, though it generally is not attached to credit from the college or university with which the professor is affiliated. See Lack, “Current Status of Research on Online Learning,” for a description of varieties of online learning, including some of the best-known MOOCs. For an excellent summary of this terrain, see Laura Pappano, “The Year of the MOOC,” New York Times, November 4, 2012. For a slightly earlier overview of the characteristics of, and the recent developments among, some MOOCs, see Abby Clobridge, “MOOCs and the Changing Face of Higher Education,” Information Today, August 30, 2012, http://newsbreaks.infotoday.com/NewsBreaks/MOOCs-and-the-Changing-Face-of-Higher-Education-84681.asp. This field is changing so rapidly that there is one or another new development almost every day.

11. Khan Academy is undergoing an assessment, conducted by SRI International’s Center for Technology in Learning, regarding the adoption and effectiveness of its materials in classrooms at twenty-one primary and secondary schools in Northern California during the 2011–12 year; a June 2012 newsletter said that a report was expected in December 2012, though as of early January 2013 no report had been published. (See “Research Update,” SRI International, Center for Technology in Learning, June 2012, http://ctl.sri.com/news/newsletter_june_2012/june_2012_news.html.) With respect to the MOOCs offering college-level courses, both Coursera and edX have expressed an interest in working with ITHAKA on assessments, and a recent piece in the Chronicle of Higher Education reported that edX is planning to test a “flipped classroom” model—combining the use of content from its online courses with face-to-face teaching—at a community college. (Marc Parry, “5 Ways That edX Could Change Education,” Chronicle of Higher Education, October 1, 2012.) According to an e-mail from Harvard’s provost, Harvard has also developed “a course support model to assist faculty in thinking about what their own HarvardX courses might look like and to facilitate experimentation in course design” and is in the process of creating “a micro development environment” that will enable faculty to design courses and smaller pieces of courses called modules (Provost Alan M. Garber, e-mail to colleagues, November 16, 2012). (HarvardX is the Harvard organization responsible for the university’s edX contributions and activities.) For-profit publishers active in this field have assembled some results that they claim, not surprisingly, make a case for their products. Disinterested third-party assessments are clearly in order. See the appendix material in Lack, “Current Status of Research on Online Learning.”

12. William J. Baumol, personal communication, November 7, 2012.

13. ITHAKA is a nonprofit organization created initially by the Andrew W. Mellon, William and Flora Hewlett, and Stavros Niarchos foundations. It is the parent of JSTOR and Portico and also operates an increasingly important strategy and research division (Ithaka S+R). Kevin M. Guthrie is the president of ITHAKA, and its board is chaired by Henry S. Bienen, president emeritus of Northwestern University. ITHAKA’s mission is “to help the academic community use digital technologies to preserve the scholarly record and to advance research and teaching in sustainable ways.”

14. The director and vice provost of the Carnegie Mellon’s Open Learning Initiative (OLI) courses define a “cognitive tutor” as “a computerized learning environment whose design is based on cognitive principles and whose interaction with students is based on that of a human tutor, that is, making comments when the student errs, answering questions about what to do next, and maintaining a low profile when the student is performing well.” They further explain that, unlike “traditional computer aided instruction,” which “gives didactic feedback to students on their final answers,” cognitive tutors “provide context-specific assistance during the problem-solving process.” (Candace Thille and Joel Smith, “Learning Unbound: Disrupting the Baumol/Bowen Effect in Higher Education,” Futures Forum, American Council on Education 2010, http://oli.cmu.edu/wp-oli/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Thille_2010_Learning_Unbound.pdf, 34).

The director and vice provost also outline the process by which “feedback loops” can be used to support classroom learning: an instructor first assigns students to work through part of the OLI course, during which time the OLI system gathers, analyzes, and organizes data about the students’ activities; the OLI system then presents the instructor with information about her students’ learning for the instructor to review; and the instructor adapts her teaching as needed (ibid., 36).

15. See William G. Bowen, Matthew M. Chingos, Kelly A. Lack, and Thomas I. Nygren, “Interactive Learning Online at Public Universities: Evidence from Randomized Trials,” May 22, 2012, available on the ITHAKA website at www.sr.ithaka.org. We are pleased to report that the study has been very well received by media outlets such as the National Review, the Boston Globe, the Chronicle of Higher Education, Inside Higher Ed, and, in particular, the Wall Street Journal (whose writer David Wessel called the report “carefully crafted” and its findings “statistically sound”). In addition to the six four-year institutions included in the study, we tried to include three community colleges. But for a variety of reasons—many logistical—this effort did not succeed, and we caution readers against simply extrapolating our findings to two-year colleges.

Courses like the CMU statistics course tested in this study exemplify what we call the interactive learning online (ILO) approach. This approach contrasts with more common types of online learning which often mimic classroom teaching without taking advantage of the unique online environment to provide “added value.”

16. As can be seen from the figure, hybrid-format students did perform slightly better than traditional-format students on three outcomes—achieving pass rates that were about three percentage points higher, scores on the Comprehensive Assessment of Outcomes in Statistics (CAOS) that are about one percentage point higher, and final exam scores that are two percentage points higher—but none of these differences passes the usual tests of statistical significance. (The CAOS test is a standardized, 40-item multiple-choice assessment designed to measure students’ statistical literacy and reasoning skills. In our study, we administered the CAOS test once at the beginning of the semester and again at the end of the semester. One characteristic of the CAOS test is that, for a variety of reasons, scores do not increase by a large amount over the course of the semester; among all the students in our study who took the CAOS test at both the beginning and the end of the semester, the average score increase was five percentage points. For more information about the CAOS test, see http://app.gen.umn.edu/artist/caos.html and Robert delMas, Joan Garfield, Ann Ooms, and Beth Chance, “Assessing Students’ Conceptual Understanding after a First Course in Statistics,” Statistics Education Research Journal 6, no. 2 (2007): 28–58.)

17. Thus, our finding is strikingly different in this consequential respect from an alternative (hypothetical) finding of “no significant difference” resulting from a coefficient of some magnitude accompanied by a very large standard error. A finding with big standard errors would mean, in effect, that we just don’t know much—the “true” results could be almost anywhere.

18. We wondered if the opposite proposition would hold—that is, we thought it possible that students who are subject to what Claude Steele has called stereotype threat might actually do better in more anonymous settings. Not proven, is the verdict of this study. The size of our study, with over six hundred participants—roughly half in the “treatment” sections and half in the “control” sections—allowed us to look more carefully than most other studies have been able to do at these more refined groupings of students. We calculated results separately for subgroups of students defined in terms of characteristics including race/ethnicity, gender, parental education, primary language spoken, pretest score (that is, score on the first administration of the CAOS test), hours worked for pay, and college GPA. We did not find any consistent evidence that the hybrid-format effect varied by any of these characteristics (see Bowen et al., “Interactive Learning Online at Public Universities,” table A6).