Legislation, litigation and implications for inclusion

The concept of inclusive education, discussed here in relation to students with disability, has emerged from a global trend aimed at ensuring the most marginalised and vulnerable students can access and participate in education (Carrington et al. 2012). International instruments such as the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD; United Nations 2008; see Chapter 4) require signatories, including Australia, to provide reasonable adjustments and individualised supports so that students with disability can access an inclusive education, without discrimination, in schools in the ‘communities in which they live’ (Article 24). The Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA; Cth) and its subordinate legislation, the Disability Standards for Education 2005 (DSE; Cth), provide the regulatory framework that governs the education of students with disability in Australian schools. This chapter will define discrimination, explain the legislative right to an inclusive education for students with disability, outline the application and limitations of Australia’s Commonwealth anti-discrimination legislation, clarify the obligations and lessons learned from past litigation, and offer practical implications for the inclusion of students with disability in Australian schools.

What is Discrimination?

When it comes to disability, discrimination is defined as:

any distinction, exclusion, or restriction on the basis of disability which has the purpose or effect of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with others, of all human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field. (United Nations 2008: Article 2)

In education, students with disability experience discrimination when they are denied, or are given limited access to, education in the school of their choice; have conditions imposed on their enrolment, attendance and/or participation that differ from those imposed on their peers; are required to participate without adjustments or supports; or are treated negatively on the basis of their disability. Discrimination can be conceptualised as ‘any practice that makes distinctions between individuals and groups so as to advantage some and disadvantage others’ (Waldeck & Guthrie 2004: 7).

Inclusive Education as a Right

Education is viewed as a critical factor in redressing the disadvantage that might arise from an individual’s personal or social circumstances. At the same time, it has the power to change discriminatory attitudes held by teachers, students and the broader school community (Masters & Adams 2018). For Australian students with disability, educational practices have evolved from the disadvantage of initially being provided no formal education, to separate provision in parent-run, charity-owned or government-funded segregated programs or schools, to attendance at mainstream schools with varying levels of integration or inclusion (Ashman 2018). Views on educational practices to best support the inclusion of students with disability have evolved alongside broader shifts in attitudes towards the inclusion of people with disability in society.

Emerging in the mid-1970s (UPIAS 1976), the social model of disability (see Chapter 2) challenged deficit views of people with disability, instead arguing that disability was imposed by society’s failure to accommodate a person’s impairments. It positioned disability as a societal failure, rather than an attribute or condition located within an individual. When the social-model lens was directed towards education, exclusionary practices were viewed as adding to the discrimination experienced by people with disability. More recently, other models have emerged, including the capability approach (Mitra 2006), the cultural model (Waldschmidt 2006) and the human-rights model (Degener 2017). The latter model emphasises the inherent worth of people with disability (Degener 2017). The impact of each of these models is evidenced by a shift from practices that simply redressed barriers that limited the education of students with disability to a commitment towards inclusive education.

One challenge associated with the right to an inclusive education is the ongoing attempts to define and redefine its meaning (Spandagou 2018). First, across Australia, when education jurisdictions have mentioned inclusive education in policy, they are typically referring to the education of students with disability, despite the term having application to all students marginalised within an education system (Anderson & Boyle 2015). Second, because inclusive education is not just an educational goal but also a methodology (Slee 2018a), policies have been written to suit the epistemological views held by each jurisdiction in relation to the education of students with disability (D’Alessio et al. 2018). In some states across Australia, this has included inclusive education being viewed as a term that reflects access to education, participation and achievement, rather than a student’s right to all of those things alongside their same-aged peers. This misinterpretation has resulted in special schools winning awards for inclusive education, and inclusive education being equated with a continuum of provision that permits degrees of inclusion that are more properly described as integration. This fluid reconceptualisation of ‘inclusive education’ has meant that Australian teachers and students, including those with disability, have not reaped all of the benefits of true inclusion.

Benefits of an Inclusive Education

Quality education of students with disability is a key goal for the United Nations, as education offers significant financial benefit, not only through increased employment and productivity of people with disability upon completion of their education, but also through the increased productivity of family members with school-aged children with disability (United Nations 2016; World Health Organization & World Bank 2011). Further, as discussed in Chapter 3, there are significant short- and long-term educational and social benefits associated with the inclusion of students with disability (Hehir et al. 2016). These benefits are classified in Table 5.1.

Slee (2018b) notes that the phrase ‘inclusive education’ is now deeply embedded in the lexicon of education, but that its initial aim of improving access, participation and outcomes for marginalised students may have been diminished by caveats within legislation. The Australian federal legislation that has been enacted to protect the rights of students with disability will be discussed in the next section.

Table 5.1: Benefits of an inclusive education (summarised from Hehir et al. 2016)

| Benefits for the student | Benefits for peers | Benefits for teachers |

|---|---|---|

• Improved educational outcomes, particularly in literacy and numeracy, and enhanced memory skills • Improved social and emotional development, leading to higher levels of engagement/friendships with peers • Increased school attendance • Reduced behaviours of concern • Increased likelihood of completion of secondary schooling • More likely to be ‘earning or learning’ post-school, and living independently |

• More accepting of diversity and reduced fear of difference, leading to a higher level of moral and ethical awareness • Enhanced skills in engaging with students who are different to them through more effective communication and greater levels of empathy and understanding • Increased self-concept • Benefit from access to educational materials that have been adapted for students with disability • No negative effect on learning outcomes, with positive effect noted in some studies |

• Higher-quality instructional strategies honed by teaching diverse learners • Access to professional learning as well as additional resourcing (typically used for staffing) that can provide further in-class support • Opportunities for collaboration with allied health and other professionals to enhance practice |

The Disability Discrimination Act 1992

The Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA; Cth) received royal assent on 5 November 1992, and passed into law. It articulated a major shift in the view of people with disability in Australia. For the first time, the focus moved beyond the viewing of disability as a deficit (the historic medical model of disability), shifting to view disability as a condition caused by barriers that can be addressed through changes in attitudes and environments (aligned with the social model of disability). The DDA was initially proposed to counter discrimination in employment, but community consultation highlighted the need for the scope of the legislation to be extended to redress discrimination in other aspects of society, including education (Poed 2016).

The DDA obligates schools, ‘as far as practicable’, to ensure that current and prospective students with disability are not treated less favourably than their peers (DDA; Cth: section 3). Schools, either directly or indirectly, may treat students with disability differently. Sometimes this is done as a form of positive discrimination: differential treatment that balances an inequity (see Chapter 2). An example is providing material in a different format to accommodate the needs of a student with a print disability. Not all students would benefit from differently formatted materials but providing these to a student with a vision impairment, for example, is a form of positive discrimination. If a school failed to provide a student with a print disability alternatively formatted materials, this would be an example of a student being treated less favourably and could be considered discriminatory. There are two types of discriminatory treatment: direct discrimination and indirect discrimination.

Direct discrimination

Direct discrimination occurs when a school decides to treat a student with a disability differently to other students on the basis of their disability. This may include a school choosing not to enrol a student because they have a disability, not permitting a student to attend a camp because of their disability, not permitting a student to study a particular subject because of their disability, and so on. If a student is not permitted to do something in a school because they have a disability, then it is likely that the school has engaged in direct discrimination.

Indirect discrimination

Indirect discrimination occurs when a school unintentionally puts in place a policy or practice that they believe to be fair, but this policy or practice has a detrimental impact on a student with a disability. An example is enforcing a ‘no hat, no play’ policy, which punishes students who fail to bring their hat to school by keeping them indoors at lunch. On the surface, the policy exists to limit later historical claims of skin cancer caused by sun exposure during lunchbreaks at school. However, for those students who dislike wearing hats because they have sensory issues, this policy may result in these students being kept indoors repeatedly during lunchbreaks, detrimentally impacting their ability to engage socially with their peers, decreasing their free time to self-regulate, and causing distress to the student. In implementing a ‘no hat, no play’ policy, the school does not set out to intentionally treat students with sensory issues differently, but it is an unintended discriminatory consequence of the policy.

Unjustifiable hardship

One exception exists in the DDA: the argument of unjustifiable hardship. This exception permits schools to make an argument that the provision of an adjustment for a student with disability would place an undue burden on the school community, and that the burden should be deemed as unreasonable thereby exempting the school from being required to make the proposed adjustment. Unjustifiable hardship will be explored in more detail later in this chapter. Due to the lack of practical guidance within legislation, the DDA included a provision that allowed for subordinate legislation to clarify the obligations embedded within the DDA. After a lengthy formulation process, the Disability Standards for Education 2005 (DSE; Cth) received royal assent on 1 March 2005.

The Disability Standards for Education 2005

The Disability Standards for Education 2005 (DSE; Cth) is a subordinate piece of legislation recognising ‘that to overcome the disadvantage arising from their disability, students with disability need to be treated differently to remove or reduce barriers to their participation in education’ (Disability Discrimination Amendment [Education Standards] Bill 2004, Cth). The phrase ‘on the same basis’ (DSE; Cth: Standard 4.2) means that the provision of education for students with disability must be of the same standard as that offered to their peers. While the DSE does not explicitly mention inclusive education, it does mandate that students must be able to enrol in, participate in and have access to services, supports and facilities provided by schools in the same way as their peers. As described in the introductory chapters to this book, these are fundamental tenets of an inclusive education.

Reasonable adjustments

The DSE obligates schools to provide reasonable adjustments to lessons, subjects, courses and extracurricular activities that enable students with disability to participate in these activities and to demonstrate their learning. Examples of adjustments considered reasonable include environmental modifications (such as tactile signs or auditory loops), pedagogical or instructional adjustments (such as visual prompts to support teacher directions), adjustments to curriculum and assessment (such as special examination provisions), as well as access to specialist support services (such as an interpreter or a visiting teacher). Where participation—even with adjustments—is not possible, schools are permitted to offer substitute activities.

The concept of reasonable adjustments was intended to promote differential treatment and positive discrimination, but it has been criticised as having a detrimental impact by directing the gaze of teachers to what students cannot do, as opposed to what they can do (Slee 2018b). When teachers are seeking additional resourcing to support a student with a disability, they are required to make a case based on the adjustments required and, to be eligible, their ‘deficit [must meet] a minimum threshold’ (de Bruin, cited in El Sayed 2018: 10). Teachers must document those areas where a student experiences difficulty, with higher needs for adjustments resulting in higher levels of additional resourcing. However, likening adjustments to deficits or resourcing misses the true meaning of the phrase as defined within legislation. Reasonable adjustments are meant to be the actions taken by a school to ensure the meaningful participation of students in the life of the school and to redress barriers to participation (Poed 2016).

Academic integrity

Like the DDA, the DSE does not obligate schools to make unreasonable adjustments. There is no requirement for teachers, or for curriculum authorities, to permit adjustments that would diminish the integrity of what is being taught, or to provide adjustments that would place an unjustifiable hardship on providers. This poses a challenge for schools, as they need to determine the exact measures that would be considered reasonable. The DSE notes that schools should ensure that:

a. course or program activities are sufficiently flexible for the student to be able to participate in them;

b. course or program requirements are reviewed, in the light of information provided by the student, or an associate of the student, to include activities in which the student is able to participate;

c. appropriate programs necessary to enable participation by the student are negotiated, agreed and implemented;

d. additional support is provided to the student where necessary, to assist him or her to achieve intended learning outcomes;

e. where a course or program necessarily includes an activity in which the student cannot participate, the student is offered an activity that constitutes a reasonable substitute within the context of the overall aims of the course or program; and

f. any activities that are not conducted in classrooms, and associated extracurricular activities or activities that are part of the broader educational program, are designed to include the student.

(DSE; Cth: Standard 5.3)

Additionally, compliance measures for the development, accreditation and delivery of curriculum require schools to ensure that:

a. the curriculum, teaching materials, and the assessment and certification requirements for the course or program are appropriate to the needs of the student and accessible to him or her;

b. the course or program delivery modes and learning activities take account of intended educational outcomes and the learning capacities and needs of the student;

c. the course or program study materials are made available in a format that is appropriate for the student and, where conversion of materials into alternative accessible formats is required, the student is not disadvantaged by the time taken for conversion;

d. the teaching and delivery strategies for the course or program are adjusted to meet the learning needs of the student and address any disadvantage in the student’s learning resulting from his or her disability, including through the provision of additional support, such as bridging or enabling courses, or the development of disability-specific skills;

e. any activities that are not conducted in a classroom, such as field trips, industry site visits and work placements, or activities that are part of the broader course or educational program of which the course or program is a part, are designed to include the student; and

f. the assessment procedures and methodologies for the course or program are adapted to enable the student to demonstrate the knowledge, skills or competencies being assessed.

(DSE; Cth: Standard 6.3)

Prevention of harassment and victimisation

A final requirement of the DSE is that schools must ensure students with disability and their associates—typically the student’s parent(s) or carer(s)—do not experience harassment or victimisation. This obligates schools to implement programs and practices that ensure their staff and students are trained so as to prevent actions intended to distress, humiliate, intimidate, offend or victimise the student or their relatives (The Disability Standards for Education 2005 Guidance Notes [Cth]).

Application and Limitations of Australia’s Anti-discrimination Legislation

The Commonwealth regulatory framework described above was created to ensure that Australian students with disability had the ‘right to comparable access, services and facilities, and the right to participate in education and training unimpeded by discrimination, including on the basis of stereotyped beliefs about the abilities and choices of students with disabilities’ (The Disability Standards for Education 2005 Guidance Notes [Cth]).

Application

Schools are obligated to make reasonable adjustments. To assess the reasonableness of a school’s actions, Standard 3.4 of the DSE states that the following should be considered:

a. the student’s disability;

b. the views of the student or the student’s associate, given under section 3.5;

c. the effect of the adjustment on the student, including the effect on the student’s:

i. ability to achieve learning outcomes; and

ii. ability to participate in courses or programs; and

iii. independence.

d. the effect of the proposed adjustment on anyone else affected, including the education provider, staff and other students;

e. the costs and benefits of making the adjustment.

(DSE; Cth: Standard 3.4)

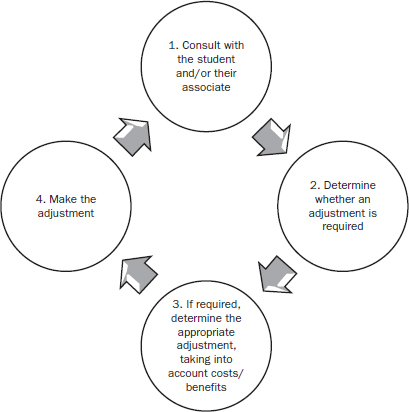

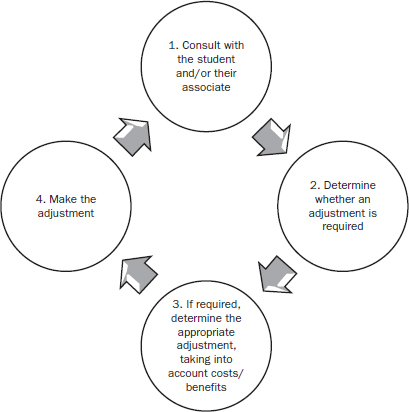

When making adjustments, the obligations for teachers are cyclical (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1. Adjustment cycle.

Limitations

Despite the enactment of federal legislation to regulate access and participation, Australian students with disability are still experiencing active and/or passive systematic discrimination resulting in reduced educational participation and opportunities (Cologon 2013; Dixon 2018; Mitchell 2017; Moss 2016; Slee 2018b). This discrimination may stem from historical benevolent or charitable views that a separate education system will keep students with disability safe and occupied. There are also more hostile views that position students with disability as violent or dangerous, a burden on teachers and peers, damaging to the academic reputation of schools, and only able to be taught by those with specialist qualifications (Mitchell 2017; Slee 2018b). An analysis of litigation serves to identify the key themes that inhibit the inclusion of Australian students with disability.

Learning from Litigation

Litigation, while stressful on all parties, does provide an opportunity to clarify obligations and refine the regulatory framework that supports inclusion of students with disability (Alvarado & Draper Rodriguez 2018). Using the framework for reasonableness presented in the first half of this chapter—and learning from litigation—the following section outlines the obligations for educators in relation to five aspects of the framework: the student’s disability, the views of the student or their parent(s) or carer(s), the effect of the adjustment on the student, the effect of the adjustment on others, and the maintenance of academic integrity.

The student’s disability

While the legislation purports to promote the social model of disability, an inherent requirement for eligibility to make a claim of discrimination still requires a diagnosis of disability by a qualified medical or allied health practitioner. The DDA (Cth) defines disability as follows:

a. total or partial loss of the person’s bodily or mental functions; or

b. total or partial loss of a part of the body; or

c. the presence in the body of organisms causing disease or illness; or

d. the presence in the body of organisms capable of causing disease or illness; or

e. the malfunction, malformation or disfigurement of a part of the person’s body; or

f. a disorder or malfunction that results in the person learning differently from a person without the disorder or malfunction; or

g. a disorder, illness or disease that affects a person’s thought processes, perception of reality, emotions or judgment or that results in disturbed behaviour;

and includes a disability that:

h. presently exists; or

i. previously existed but no longer exists; or

j. may exist in the future (including because of a genetic predisposition to that disability); or

k. is imputed to a person.

To avoid doubt, a disability that is otherwise covered by this definition includes behaviour that is a symptom or manifestation of the disability.

(DDA; Cth)

This broad definition does not match the criteria used by education jurisdictions to determine additional resourcing allocations for students with disability (see Chapter 6), raising questions as to whether the legislation affords the protections it set out to deliver for all, or only some, students with disability (O’Connell 2017). There is a widely held assumption by Australian educators that adjustments need to be provided only for those students who are eligible for individually targeted funding (Graham et al. 2018). This creates a chasm into which students with disability who are ineligible for funding fall (Foreman 2017). In Australia, this typically impacts students whose disability diagnosis sits on the cusp of funding eligibility; those whose diagnosis fluctuates, causing them to fall into and out of funding eligibility; and those who have a diagnosis but fail to meet eligibility criteria (Poed 2016). There is also a lack of consistency between sectors and states. As discussed in Chapter 6, the Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability (NCCD) was designed to address these issues by focusing on the adjustments needed to enable students with disability to access curriculum and instruction, irrespective of disability category or diagnosis, across all school sectors in Australia. The key take-home message for educators is that, regardless of the criteria used to determine which students are eligible for targeted resourcing, the definition provided above outlines all students who have a legislated right to reasonable adjustments.

Educators’ Obligations under the Legislation

Obligation to consult

The DSE obligates schools to consult students, or their associates (typically parent[s] or carer[s]), in relation to the adjustments required to their educational program (Poed 2018). The reality in Australian schools is that students are rarely consulted in relation to adjustments, particularly if they have a severe disability (Poed 2016; Wilson et al. 2015). There needs to be greater opportunities for students to make a meaningful contribution to decisions about their educational program. While some students, or more likely their associates, have an opportunity to do this during Individual Education Planning meetings (known by various names across Australia), not all students with disability are required, under jurisdictional policies, to have a plan that documents their needs. Individual plans have typically been reserved for students who receive additional resourcing through the relevant sector-eligibility criteria. As described earlier, however, these criteria do not include all students with disability entitled to reasonable adjustments under the broader DDA definition. Those students who do not receive additional resourcing are rarely consulted in relation to adjustments made to their program, which is a breach of the DSE. Processes and practices that educators can adopt to support the consultation process with students are described in Chapter 11. Consulting with parents is discussed in Chapter 14 and professional consultation is described in Chapter 15.

Another interesting learning from litigation is that the obligation to consult does not extend to acting on the information provided through consultation. Where a school can demonstrate that it is not in the best interests of the student to provide the adjustments sought by the student or their associate, or where acting on these requests would cause a school to breach a policy, courts will permit the school to ignore the advice received in the process of consultation. One example of this, from litigation, is in relation to restraint. In one Australian case, a family sought to have their child restrained as a strategy to minimise self-injurious behaviour, providing supporting documentation from medical practitioners (see Phu v. State of NSW, 2008; CP obo HP v. NSW Department of Education and Training, 2008; Phu v. State of NSW, 2009; Phu v. NSW Department of Education and Training, 2010; Phu v. NSW Department of Education and Training, 2011). The school was able to successfully argue that the self-injurious behaviour could be addressed by improving the student’s communication system, and that the policy on restraint did not permit schools to use the approach as a preventive strategy, but rather only in the event of an unforeseen circumstance that posed a serious risk to the child, or others.

Obligation to consider the effect of adjustments on the student

The benefits of providing adjustments to students with disability are clear. Adjustments provide access to learning, increase participation, allow the student’s learning to be measured, and improve engagement. The courts will balance these benefits against costs when determining whether adjustments are reasonable. For example, parents sometimes seek assistance for their child’s learning by way of the appointment of a full-time teacher aide. When making a determination as to whether this constitutes a reasonable adjustment, courts consider not just the cost of providing this service, but also the impact on the learner. For example, as discussed in Chapter 16, a full-time aide may diminish opportunities for the student to engage with peers during group work or play; a teacher may delegate responsibility for the learning program for that student to the aide, thereby denying the student the benefit of access to the teacher as expert; or the teacher may delegate responsibility for home-school communication to the aide. In these cases, courts have ruled that the provision of an aide is not a reasonable adjustment.

Part-time attendance has also come to the attention of the courts. While some schools have successfully used part-time attendance to support the reintegration of students experiencing medical or mental-health conditions, others have used part-time attendance as a punitive approach to address student behaviour. These cases have not been viewed favourably by courts, as the student is being denied a benefit—full-time access to learning—on the basis of disability.

Obligation to consider the effect of the adjustment on others

Courts have also paid attention to the impact of adjustments on peers, the teacher and the broader school community. While attention usually turns to the costs of students with disability in schools, as Hehir and colleagues (2016) showed, there are many benefits for peers learning alongside students with disability. Courts will consider any impact of disability or behaviour on the learning of peers, on teacher stress and on student and staff safety, but only where a school can show that it has provided appropriate adjustments to support behavioural change.

Obligation to maintain academic integrity

There has been limited attention in school discrimination cases in relation to academic integrity. Where attention has been paid, it has been in relation to matters such as what constitutes a reasonable substitute for a planned learning experience if the provision of adjustments were insufficient to allow a student to access and participate in the experience. A growing area for mediation has been the attendance of students with disability at school camps, excursions and extracurricular activities. On these matters, the legislation is clear. Schools are expected to provide reasonable adjustments enabling students with disability the opportunity to engage on the same basis as their peers.

Implications for Inclusion

Implications for system change

Policy has the power to change professional practice. Schools must comply with policy for their actions to be defensible. As such, the following recommendations are offered for systemic change:

• The obligation to adjust causes teachers to turn their focus on the individual and their needs rather than to reflect on their curriculum and pedagogy; some have argued this as a deficit of the legislation. There are calls, instead, for legislation to obligate systemic changes to curriculum, particularly in relation to special provisions within assessment policies, with a stronger emphasis on supporting diverse learners using universal approaches to curriculum, pedagogy and assessment (see Chapter 8).

• Consideration should be given, at the system level, as to how the views of students who are ineligible for additional resourcing in relation to adjustments to their educational program can be documented (Poed 2016, see also Chapter 11).

• Schools would be able to better support all learners with disability if the criteria for additional resourcing mirrored the definition of disability provided in the DDA. Further, this would limit litigation claims from those students who are presently unfunded. This is the intent of the Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability, although work to align the NCCD with legislative obligations is ongoing.

• A clearer policy position in relation to part-time attendance would assist schools.

• Further consideration is needed at the system level regarding the provision of specialist support services, such as the quantity and quality of Auslan support, the timeliness of accessible print material delivery, and the variable nature of allied health support dependent on postcode (Parliament of Australia [The Senate Education and Employment References Committee] 2016).

Implications for principals

Legal literacy, while critical for principals and teachers, appears to be lacking (Butlin & Trimmer 2018; Trimble & Cranston 2018). There are some critical considerations for principals in relation to inclusion:

• Principals must ensure that the process to enrol at their school is accessible for all families, and that when considering applications, students with disability are considered according to the same criteria as all other students.

• At the point of enrolment, if a family discloses that their child has a disability, this information should be used to plan adjustments rather than as a reason to reject the student’s enrolment. Urbis (2015) found that a fear of discrimination, particularly in non-government education settings, led to parents not disclosing their child’s disability at the point of enrolment.

• Once enrolled, students with disability should have opportunities to engage in all subjects or courses offered by the school. Having a disability that impacts on communication or literacy does not automatically entitle schools to withdraw students from second-language learning; having a disability that impacts on learning does not permit the school to force the student to study a less academic pathway in secondary settings. The same process for subject and course selection should be applied to all learners.

• Where funding has been allocated to schools for the provision of support services, schools need to ensure that the student receives these services, and that they are not reallocated to other students who may present with higher needs but were ineligible for resourcing.

• Principals are obligated to ensure that policies and programs are in place to prevent the harassment and victimisation of students with disability. If these do occur, principals are further obligated to ensure that they are addressed.

• In remote locations where access to staffing can be limited, principals are asked to consider the negative implications of appointing parents as a teacher aide to support the learning of their child (Urbis 2015).

Implications for teachers

The review of the DSE (Australian Government [Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations] 2012) showed that teachers were aware of the existence of the DSE, but needed ongoing training to understand its impact. Findings from litigation suggest that teachers would enhance the inclusion of students with disability through the adoption of the following practices:

• All students with disability that meet the DDA criteria provided earlier are entitled to reasonable adjustments. Teachers should plan these adjustments with the student and/or their family, and ensure that they provide these to the student as planned so that the student can participate in learning experiences on the same basis as their peers.

• Teachers should monitor classes to ensure that students with disability are not subjected to harassment or victimisation, and address these behaviours if they occur in accordance with school policy.

• Where specialist or medical assessments have been completed, teachers need to consider recommendations within these reports and plan to adopt these recommendations where appropriate. Where not appropriate, teachers should discuss their concerns with the principal so that further consultation can occur with the student and their family.

• When a teacher makes an adjustment to a student’s educational program, learning experiences or assessment tasks, records of this adjustment should be kept to support longitudinal educational planning and decision-making, and as evidence for the NCCD (see Chapter 6).

• Teachers are responsible for the design and delivery of educational programs. Where additional funding has been provided to engage a teacher aide, the teacher cannot delegate this responsibility to the aide.

Conclusion

Australia’s regulatory framework was designed to promote the inclusion of people with disability within all facets of society. For students with disability, the legislation is meant to promote engagement in schools and protect students from discrimination. Since its assent in 1992, the DDA has not achieved its objectives, as students with disability are still excluded from—or provided limited access to—high-quality inclusive education. To achieve the vision of an equitable society, schools need to address the systemic and structural barriers that inhibit students with disability. This includes deeper consideration of the content, pedagogy, assessment and engagement strategies that promote the full inclusion of students with disability. To achieve this, educators need to both know and fulfil their obligations under international humanrights law and national anti-discrimination legislation.

References

Alvarado, J.L. & Draper Rodriguez, C., 2018, ‘Education of students with disabilities as a result of equal opportunity legislation’, in K. Trimmer, R. Dixon & Y.S. Findlay (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Education Law for Schools, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 297–314

Anderson, J. & Boyle, C., 2015, ‘Inclusive education in Australia: Rhetoric, reality and the road ahead’, Support for Learning, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 4–22

Ashman, A., 2018, ‘The foundations of inclusion’, in A. Ashman (ed.), Education for Inclusion and Diversity, 6th edn, Melbourne: Pearson, pp. 2–37

Australian Government (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations), 2012, Report on the Review of the Disability Standards for Education2005, <http://education.gov.au/disability-standards-education>

Butlin, M. & Trimmer, K., 2018, ‘The need for an understanding of education law principles by school principals’, in K. Trimmer, R. Dixon & Y.S. Findlay (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Education Law for Schools, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 3–21

Carrington, S., MacArthur, J., Kearney, A., Kimber, M., Mercer, L., Morton, M. & Rutherford, G., 2012, ‘Towards an inclusive education for all’, in S. Carrington & J. MacArthur (eds), Teaching in Inclusive School Communities, Milton: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 3–38

Cologon, K., 2013, Inclusion in Education: Towards equality for students with disability, Issues Paper, Macquarie Park: Macquarie University, Child & Families Research Centre

D’Alessio, S., Grima-Farrell, C. & Cologon, K., 2018, ‘Inclusive education in Italy and in Australia: Embracing radical epistemological stances to develop inclusive policies and practices’, in M. Best, T. Corcoron & R. Slee (eds), Who’s In? Who’s Out? What to do about inclusive education, Leiden: Brill, pp. 15–32

Degener, T., 2017, ‘A new human rights model of disability’, in V. Della Fina, R. Cera & G. Palmisano (eds), The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: A Commentary, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 41–59

Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA), Cth, <www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2010C00023>

Disability Discrimination Amendment (Education Standards) Bill 2004 [2005]: Second reading, Cth, <www.humanrights.gov.au/disability-discrimination-amendment-education-standards-bill-2004-2005-second-reading>

Disability Standards for Education 2005 (DSE), Cth, <www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2005L00767>

Dixon, R., 2018, ‘Towards inclusive schools: The impact of the DDA and DSE on inclusion, participation and exclusion in Australia’, in K. Trimmer, R. Dixon & Y.S. Findlay (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Education Law for Schools, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 283–95

El Sayed, S., 2018, ‘Funding for students with additional needs’, Independent Education, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 10–12, <https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=726231445329404;res=IELHSS>

Foreman, P., 2017, ‘Legislation and policies supporting inclusive practice’, in P. Foreman & M. Arthur-Kelly (eds), Inclusion in Action, 5th edn, South Melbourne: Cengage Learning, pp. 50–85

Graham, L.J., Tancredi, H., Willis, J. & McGraw, K., 2018, ‘Designing out barriers to student access and participation in secondary school assessment’, The Australian Educational Researcher, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 103–24

Hehir, T., Grindal, T., Freeman, B., Lamoreau, R., Borquaye, Y. & Burke, S., 2016, A Summary of the Evidence on Inclusive Education, <https://alana.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/A_Summary_of_the_evidence_on_inclusive_education.pdf>

Masters, G. & Adams, R., 2018, ‘What is “equity” in education?’, Teacher, 30 April 2018, <www.teachermagazine.com.au/columnists/geoff-masters/what-is-equity-in-education>

Mitchell, D., 2017, Diversities in Education: Effective ways to reach all learners, Milton Park: Routledge

Mitra, S., 2006, ‘The capability approach and disability’, Journal of Disability Policy Studies, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 236–47

Moss, J., 2016, ‘Learner diversity, pedagogy and educational equity’, in R. Churchill, S. Godinho, N.F. Johnson, A. Keddie, W. Letts, K. Lowe, J. Mackay, M. McGill, J. Moss, M. Nagel, K. Shaw, P. Ferguson, P. Nicholson & M. Vick (eds), Teaching: Making a difference, 3rd edn, Milton: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 152–84

O’Connell, K., 2017, ‘Should we take the “disability” out of discrimination laws? Students with challenging behaviour and the definition of disability’, Law in Context, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 108–28

Parliament of Australia (The Senate Education and Employment References Committee), 2016, Access to Real Learning: The impact of policy, funding and culture on students with disability, <www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Education_and_Employment/students_with_disability/Report>

Poed, S., 2016, ‘Adjustments to curriculum for Australian school-aged students with disabilities: What’s reasonable?’, PhD thesis, Brisbane: Griffith University

—— 2018, ‘Student voice and educational adjustments’, in K. Trimmer, R. Dixon & Y.S. Findlay (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Education Law for Schools, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 335–51

Slee, R., 2018a, Defining the Scope of Inclusive Education, Think piece prepared for the 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report, <repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/handle/MINEDU/5977>

—— 2018b, Inclusive Education Isn’t Dead, It Just Smells Funny, Milton Park: Routledge

Spandagou, I., 2018, ‘A long journey: Disability and inclusive education in international law’, in K. Trimmer, R. Dixon & Y.S. Findlay (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Education Law for Schools, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 413–28

The Disability Standards for Education 2005 Guidance Notes, Cth, <www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2005L00767/Supporting%20Material/Text>

Trimble, A. & Cranston, N., 2018, ‘Education law, schools and school principals: What does the research tell us?’, in K. Trimmer, R. Dixon & Y.S. Findlay (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Education Law for Schools, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 23–38

United Nations, 2008, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), <www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html>

—— 2016, General Comment No. 4, Article 24: Right to Inclusive Education, <www.refworld.org/docid/57c977e34.html>

UPIAS, 1976, Fundamental Principles of Disability, London: Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation

Urbis, 2015, Final Report on the 2015 Review of the Disability Standards for Education 2005, <https://docs.education.gov.au/documents/final-report-2015-review-disability-standards-education-2005>

Waldeck, E. & Guthrie, R., 2004, Disability Discrimination in Education and the Defence of Unjustifiable Hardship, Perth: Curtin University of Technology

Waldschmidt, A., 2006, ‘Brauchen die disability studies ein “kulturelles Modell” von behinderung?’, in M. Dederich & W. Jantzen (eds), Behinderung und Anerkennung, Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhamme, pp. 83–96

Wilson, A., Poed, S. & Byrnes, L.J., 2015, ‘Full steam ahead: Facilitating the involvement of Australian students with impairments in individual planning processes through student-led program support group meetings’, Special Education Perspectives, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 15–25

World Health Organization & World Bank, 2011, World Report on Disability, Geneva: World Health Organization