Putting students at the centre

JENNA GILLETT-SWAN, HALEY TANCREDI & LINDA J. GRAHAM

Putting students at the centre of the learning and teaching process requires a shift from the way we currently perceive and deliver school education. It is a mindset that conceives of each student as an individual with unique talents and aspirations, and as the holder of personal insights that can help teachers to better craft their teaching. It signals a departure from the old ‘factory model’ of schooling and is consistent with recent calls for greater personalisation of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment to improve outcomes for all students (Gonski et al. 2018). Putting students at the centre requires teachers and school leaders to consult students about their learning; however, genuine consultation requires teachers and school leaders to both enable and listen to student voice in all its forms. These practices of enabling and respecting voice, and consulting and communicating with students, are embedded in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, United Nations 1989) and the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (Standards 3.5 and 3.6; AITSL 2018), both of which have a bearing on educational practice. Teachers have additional responsibilities for students with disability for whom consultation is a human right under the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD; United Nations 2008), and there is also a requirement for educators to consult in order to meet their obligations under the Disability Standards for Education 2005 (DSE; Cth) (see Chapters 4 and 5). No longer is it a question of whether students should be consulted about their education; rather, the question is how to consult students—including those with disability—in authentic and meaningful ways. This chapter explores methods of eliciting and responding to students’ voices that are inclusive of students with disability, including those with communication difficulties.

Hearing and Responding to the Voices of All Students

All students are unique and, as their experiences and perceptions are often far removed from those of their teachers, their perspectives cannot be intuited by adults. To fully understand students’ points of view, all voices need to be heard and acted upon. Eliciting and listening to student voice, however, may feel threatening for teachers and school leaders who are charged with the responsibility of managing classrooms and schools that to this day still rely on a compact of adult authority and student compliance. The adoption of democratic processes, such as voice-inclusive practice (Gillett-Swan & Sargeant 2018), can feel risky in such environments. Teachers and school leaders may feel that they are inviting anarchy and/or that they will not like what they hear back. It takes courage to allow students to speak back to power, and even greater courage to listen to and act on their views. Yet it is a necessary step to achieve Goal 2 of the Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (MCEETYA 2008: 8), which aims for ‘all young Australians to become successful learners, confident and creative individuals, and active and informed citizens’. The ability to communicate, to act with moral and ethical integrity, to commit to national values of democracy and to participate in civic life are all listed as essential elements of active and informed citizenship in the Melbourne Declaration. Yet despite the Declaration being in place for over a decade, children and young people are infrequently provided with an opportunity to have input into what happens to them at school, or they are offered only tokenistic involvement opportunities (Lundy 2018).

Research has documented clear benefits from student-centred approaches to education, which have been shown to contribute positively to academic and social outcomes, foster student agency, and position students as competent social actors with the ability to enact or participate in change (Harris et al. 2013; Rudduck & Fielding 2006). However, such approaches, starting with the elicitation of student voice, must be conducted carefully to mitigate known risks. One risk is that some voices may dominate, drowning out less dominant yet equally valid views. This raises another risk, which is that the most common preferences and the environment they produce may be alienating to other students. For example, very sociable students may express a desire for common areas and group learning, whereas introverts will experience significant stress in such environments. It may also be the case that only some students are comfortable expressing their views, and that what might appear to be the majority view is simply the view of those who are confident enough to make their voice heard. Students on the autism spectrum (Saggers et al. 2016), students with communication difficulties (McLeod 2011) and students with emotional and behavioural difficulties (Cefai & Cooper 2010) are at particular risk of not being heard. This can occur because students in these groups can find it difficult to communicate verbally, and their behaviour—which is a form of non-verbal communication—becomes the indicator of meaning. Not surprisingly, they are often misunderstood and punished when they are actually trying to convey their distress.

Effort must be made to include the perspectives of students in these groups; however, educators must take care to not coerce students, as the choice to remain silent should also be considered an expression of voice (Gillett-Swan & Sargeant 2018). To be inclusive of all students’ voices and to respect the valuable contribution that their voices can offer, time and space must be allocated for the purpose of listening and responding to students within curriculum planning, pedagogical practices and classroom interactions. However, seeking and responding to the voices of students are not ad hoc processes, nor are they easy (Rudduck & Fielding 2006). In the next section, we present a well-known model that schools can use as a framework to seek and respond to student voice, along with a case-study example of how this was adopted with considerable success in a large secondary school serving a diverse disadvantaged community in south-east Queensland.

Fostering Participation through Student Consultation

The Lundy model of participation (Lundy 2007) provides a useful starting point for the application of children’s participatory rights in educational practice. It is one of the most influential models of child participation, with impact across the three domains of policy, research and practitioner practice. In pulling together the four spheres of space, voice, audience and influence, the model provides a clear, practical and sequential process to foster participation through student consultation. It does this in a way that respects the indivisibility and interrelatedness of different rights affordances. In other words, it does not pit rights against one another. Instead, the process shows the interrelatedness of different rights in enactment. The process as conceptualised through the four spheres is as follows.

Sphere 1: Space

Adults must first provide a safe space for students to express their views, and they should encourage them to do so without coercion or consequence. Adults need to proactively and intentionally provide these spaces, rather than only seeking student input in response to predetermined agendas. A proactive pursuit of student perspectives would include eliciting input on exactly what matters affect them, and to what extent they would like to be involved in conversations and decisions about these matters (Lundy 2007). It is important to remember that if students indicate they do not wish to be involved in consultation about a particular matter at one point in time, this does not automatically exclude them from future conversations or consultations about their involvement. Nor does it mean that students should be forced to participate when they do not want to. Space alone is not sufficient, however, as children may require assistance and support in expressing their views—particularly if these opportunities have not been provided to them previously.

Sphere 2: Voice

Meaningful voice opportunities require adequate time provisions, appropriate information and adult receptiveness to listening to and acting upon children’s expressed views (Lundy 2007). Some students may respond with scepticism about intention or be wary of sharing their perspectives; as we discuss later in this chapter, this can be addressed through the building of trust, the development of rapport, the minimisation of power relations and the provision of multiple opportunities for students to express their views. If students choose to remain silent despite these provisions, their silence should be respected as an expression of voice (Gillett-Swan & Sargeant 2018).

Sphere 3: Audience

Adults must also listen to students’ expressed views and opinions, and take their perspectives seriously, providing an audience for their perspectives. Lundy (2007) describes the need for adult attentiveness to verbal and non-verbal ‘voice’ expressions and how this may require additional training in active listening skills. Audience also requires students’ voice expressions to be communicated to those with the power to enact change or action.

Sphere 4: Influence

Students’ perspectives must also be acted upon. This enables influence of children’s expressed views to enact the provision of the right for their opinions to be given ‘due weight’ in accordance with the CRC (United Nations 1989). A common misunderstanding about acting on children’s views is that a child’s expressed preference automatically outweighs the views of other stakeholders—but this is not the case. The CRC provides all children with the right to express their views in all matters affecting them, and for their views to be taken seriously and acted upon by adults. However, this right does not extend to children’s views vetoing or overriding the views of others. Instead, it emphasises the importance of ensuring that children are provided with the opportunity to have a ‘seat at the table’, and to have their views and opinions considered, incorporated and taken seriously. Children’s perspectives must be sought and incorporated in the same way that adults consult with other stakeholders, and decisions must be based on careful integration and consideration of all perspectives. This practice supports the multiple representations of perspective and experience, even when they are diverse or divergent. While some adults may be resistant to involving students, ‘respecting children’s views is not just a model of good pedagogical practice (or policy making), but a legally binding obligation . . . [that] applies to all educational decision making’ (Lundy 2007: 930). In some cases, this may also require a disruption to the beliefs of some adults about children’s capabilities.

Voice-inclusive practice

Voice-inclusive practice builds on Lundy’s model of participation by putting student views and opinions at the centre of educational activity (Gillett-Swan & Sargeant 2019). In this way, voice-inclusive practice initiates educational partnerships between adults and children so that voice may be authentically and meaningfully integrated into everyday educational practice. These partnerships need to value and embrace student contributions to their educational experience by ‘engaging with the child as both a recipient and as a key participant in the learning process’ (Sargeant & Gillett-Swan 2019: 127). Seeking and including the perspectives of all stakeholders across all matters affecting them through voice-inclusive practice maintains close alignment to student-centred educational principles. One matter of increasing educational interest and relevance to multiple stakeholders is student wellbeing. Few schools or systems, however, genuinely consult students on what wellbeing means to them or what they think will help to improve their wellbeing at school.

A Queensland Case Study

The following case study of a large secondary school in south-east Queensland, Australia provides an example of how student-voice initiatives helped guide reform to improve school belonging and student wellbeing (Gillett-Swan & Graham 2017). The participating school was situated just outside Brisbane.

The school’s leadership team had been driving reform for several years, and the school had developed a reputation for excellence, especially in sport. Enrolments had increased as a result of improving student outcomes, such that the school had become one of the largest in the state. At the time of the study, more than a third of its students were from a language background other than English, with a large proportion of students from Pacific Islander families. Almost one in ten students were Indigenous. With increased size and student diversity, however, comes greater complexity. When faced with these challenges, together with performance indicators set and monitored by both regional and central offices (see Chapter 10), leadership teams may feel the impulse to exert control through homogenising practices that affirm the hierarchical order.

Putting students at the centre and encouraging them to express their views are the antithesis of hierarchical control. This, however, is what schools must do to discover what really affects students, and where reform is needed and will have the most leverage. Genuine engagement with students takes courage and leadership from educators who not only listen with an open mind but who also actively respond to student feedback in ways that will lead to genuine change. Key staff at this school had already identified student wellbeing as the next goal in their school improvement journey, and they saw this project as an opportunity to help realise their reform objectives.

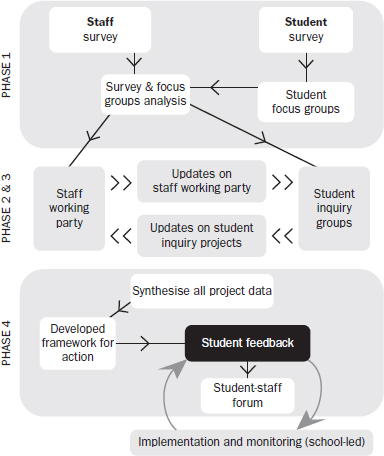

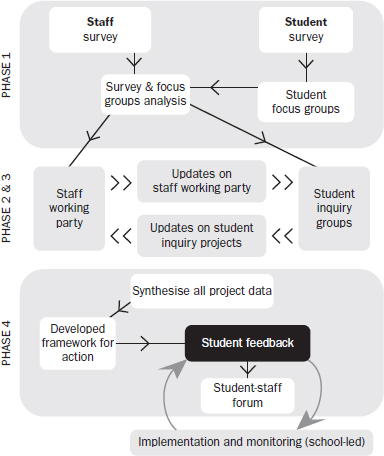

The research project on which this case study is based began in 2018 with a survey that asked students in Years 7–10 about their wellbeing at school and used the responses to identify opportunities for change (Phase 1). A similar survey was distributed to school staff, with the aim of determining similarities and differences in the conceptualisation of wellbeing and perceptions between groups. This phase had the added benefit of providing a wellbeing ‘temperature gauge’ that could act as a measure to assess the impact of the initiatives developed in subsequent phases (see Figure 11.1). Focus groups were then conducted with students across Years 7–10 to discuss the survey responses. Care was taken to include a variety of students to test the salience of survey themes.

Phases 2 and 3 occurred concurrently. Following initial integrative analysis of the Phase 1 data, a staff working party was developed to support interpretation and further exploration of the key issues identified by both students and staff (Phase 2). The staff working party consisted of eleven staff members (the wellbeing coordinator, a deputy principal, the facilities manager, the business manager, five heads of year and two guidance officers) plus the university project team. At the same time, a multi-year-level student inquiry group was formed to investigate the findings emerging from the student survey and focus groups in more depth (Phase 3). The student inquiry group comprised 21 students (thirteen females and eight males) from Years 7–10. These students then formed seven smaller ‘wellbeing inquiry project’ groups with two to five students in each.

The student inquiry groups each examined the Phase 1 findings, identified a topic of relevance to their group and then conducted a student inquiry project to learn more about their chosen issue through research with their peers. Connections between the student inquiry groups and the staff working party were created by the university project team and school wellbeing coordinator, who acted as intermediaries between both groups. Information about the activities of the groups was continually fed forwards and backwards between the staff working party and student inquiry groups, demonstrating to students that school staff valued their perspectives. This process also supported the further development of positive staff–student relationships.

Figure 11.1. Research approach (Gillett-Swan & Graham 2017).

In the final integrative phase of the project, the student inquiry groups presented their findings and key implications to the school leadership via a student forum, where both students and staff had the opportunity to seek additional information and provide additional insight. Concurrently, the staff working party used the interpretations and data generated through all phases of the research to determine actionable ways to address and/or improve the issues identified. These actionable strategies (including policy review, streamlining of processes, and inclusion of extra support, resources and passion classes) were then taken back to the whole student body for further input.

These processes were compatible with each component of Lundy’s model of participation (Lundy 2007). For example, Phases 1 and 2 provided direct opportunities for multiple spaces and opportunities for voice. Opportunities for meaningful student participation at the centre of the project were further enabled through the provision of time and regular opportunities for direct student engagement. For example, as most of the project activities occurred over a period of almost a year, this act of ‘giving time’ helped fortify student contributions. Further, the frequency of their involvement over the duration of the project provided multiple opportunities for students to develop a considered and informed view. Phase 3 enabled audience and influence, while also providing opportunities for adults at the school with the power to act upon matters raised by the students to examine and adjust their own perspectives about students’ capabilities—with support from the researchers who acted as critical friends. Students were at the centre of subsequent decision-making, as those with the power to act upon and instigate change took students’ expressed views and opinions seriously. Working with students in considering appropriate actions also enabled opportunities for consulting with students to become sustainable practice.

What did the students and staff say?

Findings from Phase 1 revealed that overall, staff members were more positive than students about what staff members were doing (for example, in the quality and quantity of support provision). Conversely, students were generally more positive than staff members about what students were doing, particularly in relation to their attitudes and effort; however, there was also a lot of variability within student responses. Trends in the data were synthesised into five ‘areas of need’ relating to students’ perspectives on: (1) the value of education, (2) respect and recognition, (3) relationships, (4) support provision, and (5) equality and fairness.

The value of education. Staff had a lower opinion of student commitment to school than the students, and this was statistically significant. For example, while students liked that there were a lot of different opportunities provided for them, and that the school prepared them for their future, they did not like the pressure to achieve or that assessment was seen as high stakes. They felt that the school paid too much attention to sport and physical appearance, and not enough to student socio-emotional needs. Students also felt that there was inconsistency in the practices and support provided by teachers, and that the current approach to behaviour management was ineffective.

Respect and recognition. Staff thought that students were being treated with respect more than the students felt that they were being respected, and this was statistically significant. In considering voice and participation specfically, just over 38 per cent of the student participants felt that adults at the school did not often listen to student concerns, and just over 42 per cent felt that adults at the school did not often act on student concerns. Thirty-one per cent of participants felt that they did not often have opportunities to make decisions at school. In thinking about the importance of seeking and acting upon children’s views, these findings are particularly revealing.

Relationships. Staff and student perceptions were generally the same in their perceptions of relationships, although there was a significant difference between male and female teachers in that males were more likely than females to say that they told students when they did a good job. In general, students liked that most teachers tried their best and felt that there were some good teachers at the school. However, students also felt as though there were not many teachers that they could trust, and not many who cared. They felt that there was a lack of follow-up when students did go to teachers with problems and that there was a long response time before action. Students also identified a lack of rapport and relationship-building opportunities with teachers.

Support provision. Staff had a higher opinion of the support available to students than students did, and this was statistically significant. Students appreciated having additional academic and non-academic support available and felt that there were genuine teachers and staff. Even so, they felt that there was a lack of support for problems, and there was perception of different support and treatment for different students. Students expressed a lack of confidence in seeking help and thought that there were not enough support options available. They also felt that there was a need for changes in the way that support in class is provided. They also questioned the effectiveness of the current support programs available at the school.

Equality and fairness. Students predominantly agreed that the rules at the school were fair, that all racial and ethnic groups were respected, and that the school would respond in an emergency. However, there were some differences by year level, with Year 7 responses being more positive about the fairness of school rules than the Year 8s and Year 10s. This was a statistically significant result. Overall, students felt that they were treated differently based on behaviour or stream (i.e. mainstream versus excellence), that the rules were not applied consistently, and that, in some cases, students or groups were targeted in rule implementation. They felt that there was a lack of inclusivity of mainstream (as opposed to ‘excellence’) students and the support received.

How did staff and students respond to the findings?

Staff response. Some of these findings were understandably confronting for staff, particularly when staff and student perspectives diverged or if there was an apparent misunderstanding about the different provisions or processes available. Initially, there was resistance from some members of the working party, who challenged or dismissed students’ feedback. After approximately three weeks of weekly working-party meetings, all staff on the working party could appreciate that, although divergent from their own, students’ perspectives had merit. By this time, the researchers had developed some rapport and trust with members of the staff working party. This, together with the leadership demonstrated by the wellbeing coordinator and deputy principal, reassured staff and ensured that they engaged with the process and with the data in good faith.

The working party’s analysis of the data highlighted several areas for action. Each area involved different levels of complexity, and some issues were able to be addressed relatively easily. For example, there was general confusion and variability in student perspectives of support provisions. In discussing student experiences of obtaining support, and staff understandings of the same processes, it became clear that this confusion was not limited to the student experience. Staff initially considered some of the support concerns highlighted by the students as already addressed through existing provisions; however, it soon emerged that the pathway to access this support lacked clarity. While students may have expressed this issue in terms of identifying a lack of support provision, it may have instead been that the support was there, but they did not know about it or how to access it. Therefore, in addition to revisiting and streamlining processes for support services and provisions, the school created an infographic and flowchart for clarity and ease of reference for staff and students alike. This is just one example of how student perspectives enabled greater insight into the student experience of wellbeing at the school and opportunities for further refinement and enhanced provision. It also emphasises the importance of collaborative interrogation of information to ensure that reactive changes are not made on adult and/or surface interpretations of what has been said.

Student response. Students were initially sceptical that the project would result in meaningful change. However, the authenticity with which the school sought, incorporated and respected student involvement and insight shows that students and staff can work together for school improvement. This is despite some of the student feedback being initially quite confronting for some staff. Responses to the follow-up survey suggested that some students appreciated that school staff were taking the time to listen and to find out more about the issues affecting students, and that they were trying to find ways to better support students and improve the school.

My reason [for indicating that my wellbeing is better this year compared to last year] is that the school listened to these surveys last year and improved on wellbeing. (Year 8 male, 2019 survey)

This was not universal, however, with others indicating that staff could go further. Students’ responses were insightful, demonstrating their understanding of the tensions that accompany change and the difficulty that staff face when engaging with student perspectives.

Listen more. With an open mind at that. I think you’re all used to the structure we’ve had for such a long time that you may not understand the change we are making. I understand it takes time to interpret. But please, listen with open ears and an open mind. (Year 11 female, 2019 survey)

Students also acknowledged that some desired changes are out of the school’s control, but still valued the effort and genuineness of the staff as they strived to do their best.

Both the students and the staff reflected on the consultation process better enabling each group to see things from the other’s perspective, in turn supporting greater levels of mutual respect and relationship development. Despite the project focusing on student wellbeing, it was clear that some students were still also conscious of and concerned about staff wellbeing.

I do understand that sometimes not everyone can be heard, but it would be really good if we are able to be heard as students and I’m sure that the teachers would like to be heard as well. (Year 9 female, inquiry group, 2018 survey)

Student consultation and involvement in this project enhanced the school’s reform efforts, as the initiatives developed through the process were based on students’ lived realities and were targeted at students’ identified needs. While some members of the staff working party were initially resistant and inclined to dismiss students’ views, the value of seeking and listening to students’ perspectives was roundly endorsed by project end. For some, it was clear that a school-reform agenda is better realised with the participation of and buy-in from students.

[A]lthough [principal] sort of says, this is your brief, this is the excellence I want to happen, I can’t see how we’re going to achieve that excellence without having that balance between the research and the student voice. It’s gotta stay. The way that we hear the student voice, and the way that it’s articulated might change . . . Those things could probably change, but that dynamic needs to continue to inform our teaching and learning practices, that’s for sure. (Participant, staff working party, 2019)

Why should schools embed student voice into inclusive school reform?

This case study provides one example of the way that direct and meaningful consultation with students can contribute to school improvement. In consulting with students, adults are placing students at the centre of their educational experiences and positioning them as key stakeholders. In doing so, positive staff–student relationships may be further developed and fortified through mutual respect and a shared understanding that the student experience matters. Consulting students is also cost-effective. There is no need for funding other than the time required for students, teachers and others to engage in the process. Taking the time to engage with students to understand different aspects of their experience may also contribute to lessening misunderstandings within adult and student perspectives. These views may initially appear divergent but could, in fact, be advocating for the same thing, as illustrated by our example of the sufficiency and suitability of support provisions. However, consulting meaningfully with students is not without its challenges.

The elevation of student voice and value associated with its relative power can be confronting for some adults, especially those who see it as a disruption to more ‘traditional’ approaches to education that position students as subordinate (Quinn & Owen 2016). Even in contexts where staff members are receptive to direct student contributions, they may still place limits on the scope of student involvement—allowing the adults to venture slightly out of their comfort zones but ultimately still maintaining the status quo. In this way, the process of engaging with students may be considered tokenistic or inauthentic by the students. This can lead to their reluctance to engage in consultation opportunities in the future, or scepticism regarding adult intention. By contrast, embedding voice-inclusive practice into everyday practice, as illustrated in this case study, supports the enactment of children’s participatory rights, rather than seeing direct student consultation as an add-on or additional burden (Sargeant & Gillett-Swan 2019). Finally, seeking student perspectives and placing them at the centre of the teaching and learning process also offer practical benefits (to teachers especially) by enabling and supporting adults to provide more focused and effective support to better meet student need. There is, however, no ‘one size fits all’ approach to voice elicitation and practice, and voice-inclusive practices need to be different for different students in different contexts. This is particularly relevant to students with disability with whom educators are legally obliged to consult.

Inclusive Education, Student Consultation and Reasonable Adjustments

As discussed in Chapter 4, the right to an inclusive education for all students, including those with disability, without discrimination and based on equal opportunity has been in place for over a decade, and was clarified recently through General Comment No. 4 (GC4), which makes clear the legal obligations of States parties that have ratified the CRPD (United Nations 2016). GC4 also states that educators are required to provide ‘participatory learning experiences’ and that students must be consulted, and their voices respected:

Consistent with Article 4, paragraph 3, States parties must consult with and actively involve persons with disabilities, including children with disabilities, through their representative organisations (OPDs), in all aspects of planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of inclusive education policies. Persons with disabilities and, when appropriate, their families, must be recognised as partners and not merely recipients of education. (United Nations 2016: paragraph 7)

The need to provide accessible consultative processes for people with disability, including children, has been mandated through the recently released CRPD General Comment No. 7:

States parties should also ensure that consultation processes are accessible—for example, by providing sign language interpreters, Braille and Easy Read—and must provide support, funding and reasonable accommodation as appropriate and requested, to ensure the participation of representatives of all persons with disabilities in consultation processes. (United Nations 2018: paragraph 45)

Of note is the clear direction provided in the statement ‘States parties should also ensure that consultation processes are accessible’ (emphasis added). Accessible consultation means that students can understand the content of a consultative conversation, can comprehend the questions that are posed to them, and are able to communicate a response that reflects their perspective. As authentic consultation requires effective, two-way communication, the consultation process may also need to be adjusted to ensure genuine participation of students with disability.

In Australia, the DSE (Cth) provides guidance for educators and education systems as to their obligations under the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA; Cth) (see Table 11.1). As discussed in Chapter 5, the DSE outlines the national legal obligations for education providers, which include the obligation to make reasonable adjustments for students with disability, as well as the obligation to consult students (or their associate) during the process of designing and implementing adjustments. The 2015 review of the DSE (Australian Government 2015) further reinforced the need to centralise the voices of students, stating that adjustments require ‘advocacy skills on the part of students with disability or their associate to achieve the best outcome’ (Australian Government 2015: 54). In order to self-advocate, however, students with disability must be given opportunities to express their views. They must also be provided with the support necessary to do so, and genuine responses to students’ voices must take place.

Table 11.1: Educators’ obligations under international law and Australian legislation

| Document | Obligations for educators and education systems | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations 1948) | Everyone has the right to education Everyone has the right to hold and freely express their opinions | International |

| Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations 1989) | All children have a right to education All children have a right to express an opinion about issues that affect them | International |

| Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) | Students with disability are entitled to reasonable adjustments | Australia |

| Disability Standards for Education 2005 (Cth) | Students with disability are entitled to reasonable adjustments Students with disability are to be consulted about adjustments | Australia |

| Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations 2008) | Students with disability have the right to inclusive and accessible education Students with disability have the right to equal and full participation | International |

| General Comment No. 4 (United Nations 2016) | Students with disability have the right to an inclusive education Students have the right to be consulted | International |

| General Comment No. 7 (United Nations 2018) | Consultation processes must be accessible | International |

Despite requirements for students with disability to be consulted about their education provision, and agreement among researchers and practitioners that students’ voices are worthy and important sources of information, the voices of students with disability continue to be largely excluded (Roulstone et al. 2016). Researchers have identified numerous inhibitors to student involvement in consultation, including varying perceptions of the relative credibility, capacity and value of the perspectives of children with disability, the costs and (assumed) difficulties associated with enabling their participation, the potential for student perspectives to undermine teacher authority, and the assumption ‘that they have no views to express; [or] . . . that their interests and experiences will always be best articulated by adult caretakers’ (Byrne & Kelly 2015: 197; see also Byrnes & Rickards 2011). Students are also not always aware of the possibilities available to them for participation in decision-making at school (Roulstone et al. 2016).

Consulting students with disability and incorporating their insights within classroom practices require a disruption to traditional teaching pedagogies (Ainscow 2005). This practice marks a clear point of departure from the segregated, special-education ‘opportunities’ of old that typically positioned students with disability (and their families) as grateful recipients of education, and offered limited consultation or collaboration with the student or their family. Inclusive education, however, positions students with disability as valued, engaged and central stakeholders in their education, and allows them to collaborate with their team in decision-making processes (see Chapter 15). As some students with disability also have communication difficulties, consultation is a step that is often dismissed as impractical. Yet the international human-rights law and legislation that applies to students with disability applies to these students, too, and schools still have an obligation to meet. There are specific processes that can be employed where a student has communication difficulties that will assist schools in meeting those obligations.

Consulting students with communication difficulties

According to research with Australian teachers, over 13 per cent of students with disability also experience communication difficulties (McLeod & McKinnon 2007). This broad group can include—but is not restricted to—students with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD), a speech sound disorder, hearing impairment, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, Down syndrome or intellectual disability, or students on the autism spectrum. As discussed earlier in this chapter, educators are obligated as per the DSE (Cth) to make reasonable adjustments for students with communication difficulties, and students must be consulted about the adjustments that are designed and implemented to support them. However, barriers within the consultation process need to be minimised or removed when consulting students with communication difficulties (Tancredi 2018).

Communication difficulties will impact the consultation process in several ways. For example, consultative conversations require all parties to engage in high-level reflection, negotiation and problem-solving. All parties to the consultation need to be able to process the shared information for meaning, integrate it with their own ideas and opinions, prioritise between group members, and finally design a plan of action or goal. The pace, linguistic complexity, level of complex and abstract content, and demands on working memory all represent possible barriers for a student with communication difficulties (Graham, Tancredi et al. 2018). Research shows that teachers are already less likely to consult students, because they are not adults, and their propensity to consult further decreases when students have a disability, especially one involving communication difficulties (McLeod 2011). Teachers also report not having an adequate understanding of communication difficulties (Dockrell & Lindsay 2001). Similar arguments are made to justify the exclusion or lack of consultation with any student due to assumptions around their relative capacities and potential contribution (United Nations 2009). In practice, this may mean that teachers overestimate a student’s communicative competence, leading to inadequate adjustment to the consultation process. The hidden nature of communication difficulties highlights the need for teachers to both ask students about the barriers they face and what helps them learn, and to use that information to proactively design curriculum and assessment that is accessible to all (Tancredi 2018). In the following section, we provide evidence-based suggestions to support teachers to meet their obligations to consult students with disability, with an emphasis on strategies that assist students with communication difficulties.

Approaches and Strategies for Student Consultation

When students are positioned at the centre of their education, they are consulted to share their insights and take part in decision-making regarding the learning environment, curriculum design, teachers’ pedagogical practices and assessment. Through a process of reflective questioning and discussion, students can express their preferences and experiences. Different situations will call for different approaches to student consultation, and some common examples are outlined in Table 11.2. While interviewing is the most commonly adopted approach, focus groups can offer a more naturalistic discussion platform for students to share their insights. A group situation will, however, require the facilitator to ensure that all students can contribute and have a genuine voice in the discussion. For students who have an established support network or team within their school, consultation may take place at regular intervals with members of the Student Support Team (SST).

For each of the above approaches to student consultation, additional strategies may be needed to ensure that students can genuinely engage in the process. The strategies discussed below have been shown to support students to engage in the process of consultation and share their thoughts and opinions. These strategies can be used with all students, but they are particularly important for students with disability and communication difficulties. A first principle for any consultation process, however, is accessibility.

The critical importance of accessible language

Student consultation typically involves the use of written or spoken language. Most teachers are proficient language users, making it difficult for them to understand the inherent language demands of the syllabus and how this impacts their own teaching, as well as the assessments they create (Graham, Tancredi et al. 2018). As adult language users, teachers also have large developmental differences to the multitude of students they teach. Mutual understanding is therefore affected by teachers’ ability to match their vocabulary to their students’ ages, as well as their socio-economic, cultural and language backgrounds. Given that students’ responses are determined by the questions that are asked, it is essential for teachers to think carefully about the words and phrases they use to construct questions and frame consultative conversations. This is important, because the challenges imposed by language are more subtle than they might appear.

Table 11.2: Example approaches to student consultation

| Approach | People involved | Activity | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interview | Student Interviewer A support person may be present for the student | Can comprise:

• a set series of questions (a structured interview); • an open discussion (an unstructured interview); or • both structured questions and unstructured discussion (a semi-structured interview). • Interviews can combine both verbal interaction and multiple means of students constructing and sharing their message. |

Interview should be transcribed verbatim to facilitate an objective record of what the student has shared. This reduces the risk that the student’s words are paraphrased, and the student’s intended meaning is diluted or changed. |

| Focus group | A group of six to eight students Facilitator(s) | An opportunity for discussion and innovative ideas that arises through interaction between the group members. | Strategies may need to be put in place to allow all students to have the opportunity to contribute. |

| Student Support Team (SST) | Student Parent(s) and/or caregiver(s) Educator(s) Case manager School principal or principal’s delegate | • Student attends all meetings. • Student’s perspective is foregrounded in the design and implementation of adjustments or decisions regarding education provision. |

Student and their family are provided written feedback based on group discussions and action plans/outcomes. |

For example, recent research with 96 nine- to sixteen-year-old students in Sydney, Australia (Graham, Sweller et al. 2018), found significant differences in the receptive and expressive vocabulary of students both with and without a history of behavioural difficulties. Anticipating that students in the first group would also have difficulties with language, the researchers carefully developed a range of interview questions that would be accessible to all students. Most questions were short, concrete and direct; however, a few questions were not. Subsequent analyses found significant differences between groups both in terms of expressive vocabulary and in their responses to the different types of questions. For instance, in response to the question, ‘What do you think your teacher thinks of you?’, students with a history of behavioural difficulties were significantly more likely to say something like, ‘I dunno, I don’t ask them’ than students without language and behavioural difficulties. The researchers had deliberately included this abstract question, as it required ‘sophisticated linguistic reasoning in addition to the ability to compare one’s perception of self in relation to the perceived perceptions of others’ (Graham, Sweller et al. 2018: 4). In other words, to answer this question students needed to interpret abstract language and impute mental states, then articulate that in a verbal response. Imputing mental states is a skill otherwise known as Theory of Mind, which is a documented weakness for students with disability affecting social communication, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Notably, concrete questions such as ‘Do you like school?’ and ‘What happened to make you start disliking school?’ resulted in more definitive responses and fewer non-responses from this group of students (Graham et al. 2016). Using accessible language is a mandatory first step in consulting students with disability, but for students with communication difficulties, it will be insufficient on its own. For these students, a range of practical strategies can be employed.

Multiple methods and means of participation/engagement

While accessible language is critical to support genuine participation, language has its own limitations. This is where using multiple methods for engaging students in consultation can minimise the barriers imposed by language. To ensure that students can fully participate in consultation, we need to think about how students’ views are sought, as this impacts what they say (Owen et al. 2004). Carefully developed visual supports and activities can assist students to comprehend a consultative discussion and to articulate their thoughts (Lyons & Roulstone 2018). The information generated can also provide non-verbal data, which is helpful when interpreting meaning for students with complex communication difficulties (Clarke et al. 2001). In addition to supporting rapport building, the use of multiple methods and opportunities to consult students can improve the student’s understanding of both the process and the questions raised during consultation. In some instances, the student may prefer to be interviewed by a person who acts as a broker of information between the student and their teacher. When used collaboratively, these approaches can help to build trust, address power imbalances and ensure mutual understanding of the student’s intended message (Merrick & Roulstone 2011).

Visual supports and activities. Visual supports and activities provide a supplementary mode for both parties to communicate information in a consultative conversation. This is necessary, because the information exchange that takes place in a verbal conversation is transient. That is, once words are spoken, they must be comprehended quickly and accurately by the listener. If this process is disrupted, the listener may forget or misinterpret what has been said by their communication partner, which can impact the listener’s response. Consultative conversations also require students to reflect on their experiences, share their opinions and express their views. The high-level and complex nature of this task risks students not understanding what has been asked, and students might not always have the vocabulary to explain the ideas they have. Visual supports and activities address both issues by providing a concrete, tangible addition to conversations, which can support all students to participate in consultation.

Visual supports can be pre-prepared (created ahead of the conversation) or produced in situ (created during the conversation). An example of a pre-prepared visual support is a list that uses text, images or a combination of text and images, which outlines options that are available for a task. When pre-prepared visual supports are used, it is important that students are given the opportunity to also contribute to the options that are available. This kind of visual aid can help students to understand the options that are available, support them to express their choice and facilitate brainstorming of other options. Drawing and mind-mapping are examples of visual aids that are created in situ. This strategy can help the student to organise and expand their thoughts by creating a static, visual record of ideas and insights. It can also enable the adult to clarify the student’s ideas in real time and can help the student to expand their thinking (Tancredi 2018).

Activities can include arts-based approaches and interactive tasks. In one study, Merrick and Roulstone (2011) encouraged students to share their experiences by giving an adult a tour of their school. During the tour, students took the adults to particular places and discussed events that were meaningful to them. Students were encouraged to take photos of places and objects during the tour. These pictures were then used as visual supports to prompt reflection and storytelling during the consultative conversation that followed. More recently in Queensland, Kucks and Hughes (2019) worked with young primary-school students to redesign their play spaces. Students were asked to create collages and models that represented their idea of a fun, sensory garden. In combination with the ideas suggested by the teaching team, these young students’ suggestions were used by the educational landscaper to create a new play space. As these examples show, hands-on activities can enable all students to express their ideas and opinions.

Multiple interviews. Asking students to share their stories requires the development of trust, as well as the active consideration and minimisation of power differentials (Merrick & Roulstone 2011). Conducting multiple short interviews provides opportunities for trust and rapport to be built, thereby reducing the potential of a power imbalance between student and interviewer. Lyons and Roulstone (2018), for example, investigated the ways that students with speech, language and communication difficulties constructed their identities, using a narrative-inquiry approach. By conducting five or six short, semi-structured interviews with each student, the interviewers built rapport, enabling the students to trust the adults with their stories. Interviewing students on multiple occasions has other benefits as well. Through multiple interviews, students are provided with enough time and exposure to become familiar with the process of consultation, and students are provided multiple opportunities to share their insights. Given that not all students will have had the experience of consultation, particularly in relation to things that happen at school, multiple interviews can also help students to understand the unique nature of consultative conversations. This strategy helps to increase the student’s participation but also mitigates any potential biases that the interviewer may bring to the interview situation. This is particularly important for students with communication difficulties, as the student’s intended message may be misinterpreted by the interviewer. For example, Tancredi (2018) interviewed students with language difficulties on two or three occasions about the adjustments that they believed helped them to learn. In the final interview, she asked students to prioritise their preferred adjustments by numbering their top three preferences (where ‘one’ indicated the most helpful adjustment). This process revealed that what the students said in initial interviews, and the frequency of discussion about a particular adjustment, did not necessarily match the student’s stated level of preference for the adjustments used by their teachers.

Engaging an impartial information broker. In some circumstances, the power relationship between students and teachers may make students reluctant to share their insights about what works for them at school with their teacher. Depending on the topic and situation, it may be inappropriate for a teacher to seek feedback from students about their own practice. This can place students in a difficult position, and they may withhold important feedback to protect their teacher’s feelings. By engaging a trusted third party in the consultative process and having students’ permission to feed their insights back to the teaching team, students may feel more comfortable about sharing their ideas and experiences (both positive and negative). This person may be another teacher, a school counsellor, a speech pathologist or a specialist teacher. Alternatively, teachers can use anonymous classroom feedback systems, such as a suggestion box into which students can submit tips for what their teachers should keep doing, stop doing and start doing to further enhance students’ learning.

Conclusion

All students have the right to an inclusive education and the right to express opinions. Internationally, these rights are provided through the CRC (United Nations 1989) and the CRPD (United Nations 2008), and they represent a student-centred approach to education. For students with disability in Australia, additional protections exist, where teachers are obligated to provide reasonable adjustments and to consult students about the adjustments that are designed and implemented, as per the DSE (Cth). As we have discussed in this chapter, students who are placed at the centre of their education experience are active participants, are consulted on issues that affect them, and are positioned as agents who can contribute to decisions and processes that take place at school. When students have a genuine voice at school, they are developing the skills of a democratic citizen. Their unique insights and reflections are valuable sources of information, which may provide innovative and dynamic solutions or outcomes. Without careful attention to the consultation process, however, students may go unheard.

To maximise success, the consultation process must be well planned to ensure that students can understand the questions posed during consultation and express their true ideas and opinions. The approach also needs to be considered and chosen based on the situation and context. A range of evidence-based strategies exists to support all students to express their views. These strategies include visual supports and activities to support verbal interaction, as well as asking clear questions that students will be able to comprehend and respond to with ease. Engaging in multiple interviews with students and engaging a third party to support the transfer of information between students and teachers can provide a supportive environment for participation and engagement. Putting students at the centre is essential for student participation and wellbeing, but its success depends on the enactment of a planned and intentional process. This may seem like a lot of work to time-poor teachers and principals, but by consulting students about their education and responding to their voices, educators are both upholding their obligations and contributing to each student’s personal and social development.

References

Ainscow, M., 2005, ‘Developing inclusive education systems: What are the levers for change?’, Journal of Educational Change, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 109–24

Australian Government, 2015, Final Report on the 2015 Review of the Disability Standards for Education 2005, <https://docs.education.gov.au/documents/final-report-2015-review-disability-standards-education-2005>

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), 2018, Australian Professional Standards for Teachers, <www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/teach-documents/australian-professional-standards-for-teachers.pdf>

Byrne, B. & Kelly, B., 2015, ‘Valuing disabled children: Participation and inclusion’, Child Care in Practice, vol. 21, no. 3, 197–200

Byrnes, L.J. & Rickards, F.W., 2011, ‘Listening to the voices of students with disabilities: Can such voices inform practice?’, Australasian Journal of Special Education, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 25–34

Cefai, C. & Cooper, P., 2010, ‘Students without voices: The unheard accounts of secondary school students with social, emotional and behaviour difficulties’, European Journal of Special Needs Education, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 183–98

Clarke, M., McConachie, H., Price, K. & Wood, P., 2001, ‘Views of young people using augmentative and alternative communication systems’, International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 107–15

Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA), Cth, <www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2010C00023>

Disability Standards for Education 2005 (DSE), Cth, <www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2005L00767>

Dockrell, J.E. & Lindsay, G., 2001, ‘Children with specific speech and language difficulties—the teachers’ perspective’, Oxford Review of Education, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 369–94

Gillett-Swan, J.K. & Graham, L.J., 2017, ‘Wellbeing matters: A collaborative approach to harnessing student voice to develop a Wellbeing Framework for Action in the middle years’, Department of Education (Queensland) Education Horizon Competitive Grant Scheme Project, ref: 2017000734

Gillett-Swan, J.K. & Sargeant, J., 2018, ‘Assuring children’s human right to freedom of opinion and expression in education’, International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 120–7

—— 2019, ‘Perils of perspective: Identifying adult confidence in the child’s capacity, autonomy, power and agency (CAPA) in readiness for voice-inclusive practice’, Journal of Educational Change, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 399–421

Gonski, D., Arcus, T., Boston, K., Gould, V., Johnson, W., O’Brien, L., Perry, L. & Roberts, M., 2018, Through Growth to Achievement: Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, <https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/662684_tgta_accessible_final_0.pdf>

Graham, L.J., Sweller, N. & Van Bergen, P., 2018, ‘Do older children with disruptive behaviour exhibit positive illusory bias and should oral language competence be considered in research?’, Educational Review, pp. 1–18

Graham, L.J., Tancredi, H., Willis, J. & McGraw, K., 2018, ‘Designing out barriers to student access and participation in secondary school assessment’, The Australian Educational Researcher, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 103–24

Graham, L.J., Van Bergen, P. & Sweller, N., 2016, ‘Caught between a rock and a hard place: Disruptive boys’ views on mainstream and special schools in New South Wales, Australia’, Critical Studies in Education, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 35–54

Harris, J., Spina, N., Ehrich, L.C. & Smeed, J., 2013, Literature Review: Student-centred schools make the difference, Melbourne: Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership

Kucks, A. & Hughes, H., 2019, ‘Creating a sensory garden for early years learners: Participatory designing for student wellbeing’, in H. Hughes, J. Franz & J. Willis (eds), School Spaces for Student Wellbeing and Learning, Singapore: Springer, pp. 221–38

Lundy, L., 2007, ‘“Voice” is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child’, British Educational Research Journal, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 927–42

—— 2018, ‘In defence of tokenism? Implementing children’s right to participate in collective decision-making’, Childhood, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 340–54

Lyons, R. & Roulstone, S., 2018, ‘Listening to the voice of children with developmental speech and language disorders using narrative inquiry: Methodological considerations’, Journal of Communication Disorders, vol. 72, pp. 16–25

McLeod, S., 2011, ‘Listening to children and young people with speech, language and communication needs: Who, why and how?’, in S. Roulstone & S. McLeod (eds), Listening to Children and Young People with Speech, Language and Communication Needs, Albury: J&R Press, pp. 23–40

McLeod, S. & McKinnon, D.H., 2007, ‘Prevalence of communication disorders compared with other learning needs in 14,500 primary and secondary school students’, International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, vol. 42, s. 1, pp. 37–59

Merrick, R. & Roulstone, S., 2011, ‘Children’s views of communication and speech-language pathology’, International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 281–90

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA), 2008, Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians, <www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf>

Owen, R., Hayett, L. & Roulstone, S., 2004, ‘Children’s views of speech and language therapy in school: Consulting children with communication difficulties’, Child Language Teaching and Therapy, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 55–73

Quinn, S. & Owen, S., 2016, ‘Digging deeper: Understanding the power of “student voice”’, Australian Journal of Education, vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 60–72

Roulstone, S., Harding, S. & Morgan, L., 2016, Exploring the Involvement of Children and Young People with Speech, Language and Communication Needs and their Families in Decision Making: A research project, London: The Communication Trust, <www.thecommunicationtrust.org.uk/media/443274/tct_involvingcyp_research_report_final.pdf>

Rudduck, J. & Fielding, M., 2006, ‘Student voice and the perils of popularity’, Educational Review, vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 219–31

Saggers, B., Klug, D., Harper-Hill, K., Ashburner, J., Costley, D., Clark, T., Bruck, S., Trembath, D., Webster, A.A. & Carrington, S., 2016, Australian Autism Educational Needs Analysis—What are the needs of schools, parents and students on the autism spectrum? Brisbane: Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism

Sargeant, J. & Gillett-Swan, J.K., 2019, ‘Voice inclusive practice (VIP): A charter for authentic student engagement’, International Journal of Children’s Rights, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 122–39

Tancredi, H., 2018, ‘Adjusting language barriers in secondary classrooms through professional collaboration based on student consultation’, MA thesis, Brisbane, Queensland University of Technology, <https://eprints.qut.edu.au/122876/>

United Nations, 1948, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, <www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/>

—— 1989, Convention on the Rights of the Child, Geneva: United Nations <https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-11&chapter=4&lang=en>

—— 2008, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), <www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html>

—— 2009, General Comment No. 12: The Right of the Child to be Heard, <www.refworld.org/docid/4ae562c52.html>

—— 2016, General Comment No. 4, Article 24: Right to Inclusive Education, <www.refworld.org/docid/57c977e34.html>

—— 2018, General Comment No. 7, Article 4.3 and 33.3: Participation of Persons with Disabilities, including Children with Disabilities, through their Representative Organizations, in the Implementation and Monitoring of the Convention, <https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRPD/C/GC/7&Lang=en>