Introduction

This introduction was specially written for the English edition of Montaillou, which is a shorter version of the French.

Though there are extensive historical studies concerning peasant communities there is very little material available that can be considered the direct testimony of peasants themselves. It is for this reason that the Inquisition Register of Jacques Fournier, Bishop of Pamiers in Ariège in the Comté de Foix (now southern France) from 1318 to 1325, is of such exceptional interest.1 As a zealous churchman – he was later to become Pope at Avignon under the name Benedict XII – he supervised a rigorous Inquisition in his diocese and, what is more important, saw to it that the depositions made to the Inquisition courts were meticulously recorded. In the process of revealing their position on official Catholicism, the peasants examined by Fournier’s Inquisition, many from the village of Montaillou, have given an extraordinarily detailed and vivid picture of their everyday life.

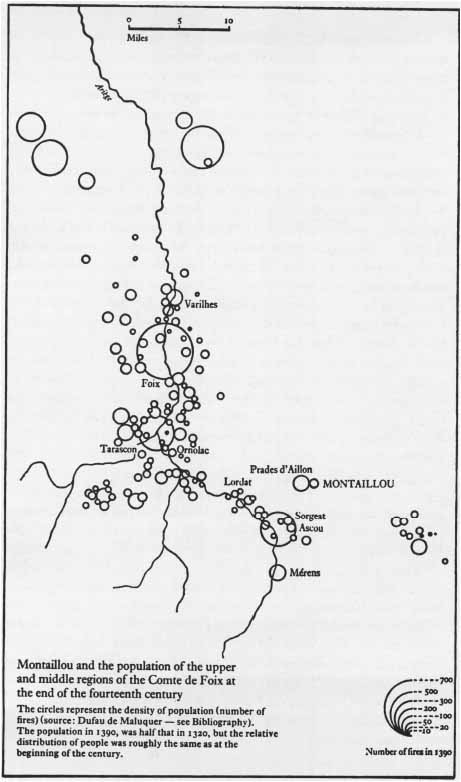

Montaillou is a little village, now French, situated in the Pyrenees in the south of the present-day department of Ariège, close to the frontier between France and Spain. The department of Ariège itself corresponds to the territory of the diocese of Pamiers, and to the old medieval Comté de Foix, once an independent principality. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries the principality, ruled over by the important family of the Comtes de Foix, became a satellite of the powerful kingdom of France. The large province of Languedoc, adjacent to Ariège, was already a French possession.

Montaillou was the last village which actively supported the Cathar heresy, also known as Albigensianism, after the town of Albi, in which some of the heretics lived. It had been one of the chief heresies of the Middle Ages, but after it had finally been wiped out in Montaillou between 1318 and 1324 it disappeared completely from French territory. It appeared in the twelfth or thirteenth centuries in Languedoc in northern Italy, and, in slightly different forms, in the Balkans. Catharism is not to be confused with Waldensianism, another heretical sect which originated in Lyons but which hardly affected Ariège. Catharism may have been based on distant Oriental or Manichaean influences, but this is only hypothesis. However, we do know a great deal about the doctrine and rites of Catharism in Languedoc and northern Italy.

Catharism or Albigensianism was a Christian heresy: there is no doubt on this point at least. Its supporters considered and proclaimed themselves ‘true Christians’, ‘good Christians’, as distinct from the official Catholic Church which according to them had betrayed the genuine doctrine of the Apostles. At the same time, Catharism stood at some distance from traditional Christian doctrine, which was monotheist. Catharism accepted the (Manichaean) existence of two opposite principles, if not of two deities, one of good and the other of evil. One was God, the other Satan. On the one hand was light, on the other dark. On one side was the spiritual world, which was good, and on the other the terrestrial world, which was carnal, physical, corrupt. It was this essentially spiritual insistence on purity, in relation to a world totally evil and diabolical, which gave rise retrospectively to a probably false etymology of the word Cathar, which has been said to derive from a Greek work meaning ‘pure’. In fact ‘Cathar’ comes from a German word the meaning of which has nothing to do with purity. The dualism good/evil or God/Satan subdivided into two tendencies, according to region. On the one hand there was absolute dualism, typical of Catharism in Languedoc in the twelfth century: this proclaimed the eternal opposition between the two principles, good and evil. On the other hand was the modified dualism characteristic of Italian Catharism: here God occupies a place which was more eminent and more ‘eternal’ than that of the Devil.

Catharism was based on a distinction between a ‘pure’ élite on the one hand (perfecti, parfaits, bonshommes or hérétiques), and on the other hand, the mass of simple believers (credentes). The parfaits came into their illustrious title after they had been initiated by receiving the Albigensian sacrament of baptism by book and words (not by water). In Cathar language, this sacrament was called the consolamentum (‘consolation’). Ordinary people referred to it as ‘heretication’. Once he had been hereticated a parfait had to remain pure, abstaining from meat and women. (Catharism, though not entirely anti-feminine, showed no great tolerance of women.) A parfait had the power to bless bread and to receive from ordinary believers the melioramentum or ritual salutation or adoration. He gave them his blessing and kiss of peace (caretas). Ordinary believers did not receive the consolamentum until just before death, when it was plain that the end was near. This arrangement allowed ordinary believers to lead a fairly agreeable life, not too strict from the moral point of view, until their end approached. But once they were hereticated, all was changed. Then they had to embark (at least in the late Catharism of the 1300s) on a state of endura or total and suicidal fasting. From that moment on there was no escape, physically, though they were sure to save their souls. They could touch neither women nor meat in the period until death supervened, either through natural causes or as a result of the endura.

Around 1200, Catharism had partly infected quite large areas of Languedoc, which at that period did not yet belong to the kingdom of France. Such a state of affairs could not be allowed to continue. In 1209 the barons of the north of France organized a crusade against the Albigensians. The armies marched southwards in answer to an appeal from the Pope. Despite the death in 1218 of Simon de Montfort, the brutal leader of the northern crusaders, the King of France gradually extended his power over the south and took advantage of the pretext offered by the heretics to annex Languedoc de facto in 1229, by the Treaty of Meaux. This annexation left lasting traces of resentment in what later became the south of France. These were revived in the twentieth century by the renaissance of Occitan regionalism. In 1244 Montségur, in Ariège, the last heretic fortress, was taken. The Albigensians who had long held out there were sent together to the stake in Montségur itself or in Bram.

But even after 1250 Catharism still showed signs of life. In the mountains of upper Ariège the Albigensian heresy even had a modest revival between 1300 and 1318. One of the centres of this revival was the village of Montaillou. Partly responsible for the recrudescence of heresy was the militant and energetic action of the Authié brothers, formerly notaries in Ariège who had become heroic missionaries of Albigensianism. But the Inquisition of Fournier and his colleagues, based in Carcassonne (Languedoc) and chiefly in Pamiers (Ariège), finally succeeded in flushing out this last pocket of resistance, by means of a detailed inquiry followed by some burnings at the stake, many sentences of imprisonment and still more penalties in the form of yellow crosses. (Just as medieval Jews wore the yellow star, so condemned heretics were forced to wear on their backs big crosses made of yellow material sewn to their outer garments.) Catharism never recovered from this final blow in 1320. The prisoners of Montaillou were the last of the last Cathars. But it was not an absolute end. For the brave fight put up by the peasants of Ariège to preserve the remains of their heterodox beliefs after 1300 foreshadowed the great Protestant revolt two centuries later.

Jacques Fournier, the person responsible for our documentary sources, seems to have been born some time during the decade which began in 1280, at Saverdun in the north of the Comté de Foix, a region which is now part of Ariège. The precise status of his family is not known, but Fournier himself was of fairly humble origin. So conscious was he of his undistinguished lineage that when he became Pope he is said to have refused to give his niece in marriage to a brilliant aristocrat who sought her hand, saying, ‘This saddle is not worthy of this horse’. But even before Jacques Fournier, there were several instances of social advancement in the family. One of his uncles, Arnaud Novel, was Abbot of the Cistercian monastery at Fontfroide. Encouraged by this model, the young Fournier also became a Cistercian monk. He went north for a while, first as a student, then as a doctor of the University of Paris. In 1311 he succeeded his uncle as Abbot of Fontfroide. In 1317, already known for his learning and severity, he was made Bishop of Pamiers, and in this new role he distinguished himself by his inquisitorial pursuit of heretics and other deviants. In his diocesan seat he kept up correct relations with the agents of the Comte de Foix and of the King of France. (Up to this point in his life, though living in Languedoc, he was pro-French.) In 1326 Pope John XXII congratulated him on his successful heretic hunt in the region of Pamiers, the congratulations being accompanied by a sheaf of indulgences. But Fournier’s activities were not confined to ideological persecution. He also managed to make agricultural tithes more onerous, imposing them on cheese, beets and turnips, which hitherto had been exempt.

In 1326 Fournier was made Bishop of Mirepoix, east of Pamiers, a move that might be interpreted as a fall from favour. He had in fact made himself unpopular in his previous diocese through his obsessional, fanatical and competent pursuit of all kinds of suspects. But the see of Mirepoix contained more parishes than Pamiers, so his new appointment seems to have been a promotion rather than a disgrace. It was followed by even more dazzling advancement. In 1327 Fournier became a Cardinal. In 1334 he was elected Pope of Avignon under the name of Benedict XII. ‘You have elected an ass’, he is supposed to have said, with his usual self-effacement, to the College which voted him into office. But, modest or not, once he had begun to wear the tiara Fournier soon showed his not inconsiderable abilities. He reacted against nepotism. Himself a monk and an ascetic, he tried to improve the morals of the monasteries. Like many intellectuals he was unskilled in practical matters, and met with little success in foreign policy. But he was at home in the field of dogma. He corrected the theological fantasies of his predecessor, John XXII, about the Beatific Vision after death. On the subject of the Virgin, he was a maculist, opposing the theory (which later triumphed) of the immaculate conception of Mary. His various pronouncements on dogma were the crown of a long intellectual career: throughout his life he engaged in vigorous, though somewhat conformist, controversy against all kinds of thinkers whom he considered to have strayed from Roman orthodoxy; his opponents included Giacomo dei Fiori, Master Eckhart and Occam. It was Fournier who initiated the building of the Palace of the Popes in Avignon, and he who invited Simone Martini there to paint the frescoes.

But it is the Pamiers period which interests us in the life of the future Benedict XII, and particularly his activity there as organizer of a formidable Inquisition court. Outbreaks of heresy even after the fall of Montségur led Pope Boniface VIII to create, in 1295, the diocese of Pamiers, including both the north and the south of the Comté de Foix, with the object of making it easier to check religious deviance. After a comparative lull there were two new inquisitorial offensives, one in 1298–1300 and another in 1308–09. In 1308, Geoffroy d’Ablis, the Inquisitor of Carcassonne, arrested the whole population of the village of Montaillou with the exception of young children.

These drives against the heretics were the work of the Dominican court at Carcassonne, which as such had nothing to do with the new see of Pamiers or the traditional Comté de Foix. The Bishops of Pamiers, although in principle they were supposed to seek out religious un-orthodoxy, for a long while preferred to lie low and not utter a word against heresy among their flock. Bishop Pelfort de Rabastens (1312–17) was so busy squabbling with his canons that he did not have time to watch over the orthodoxy of his diocese. But with Jacques Fournier, who succeeded him in 1317, things changed: the new Bishop took advantage of a decision of the Council of Vienna (1312) which stipulated that henceforward, in the courts of the Inquisition, the powers of the local Bishop were to be used in support of the Dominican official who had up till then been in sole charge of repression. So in 1318 Fournier was able to set up his own inquisitorial ‘office’. He ran it in close association with Brother Gaillard de Pomiès, delegate of Jean de Beaune, who was the representative of the Inquisition of Carcassonne. Pomiès and Beaune were both Dominicans.

The new court at Pamiers was very active all the time its founder was in power locally. Even when Jacques Fournier was made Bishop of Mirepoix in 1326 the ‘office’ at Pamiers did not disappear. But his successors did not believe in overdoing things, and repression on the local level slumbered, leaving the people of the Comté de Foix in peace. So it is only during Fournier’s episcopate that the tribunal at Pamiers gives us detailed information on peasant life in Occitania.

At the head of the ‘office’ was of course Jacques Fournier himself, a sort of compulsive Maigret, immune to both supplication and bribe, skilful at worming out the truth (at bringing the lambs forth, as his victims said), able in a few minutes to tell a heretic from a ‘proper’ Catholic – a very devil of an Inquisitor, according to the accused. He proceeded, and succeeded, essentially through the diabolical and tenacious skill of his interrogations; only rarely did he have recourse to torture. He was fanatical about detail, and present in person at almost all the sittings of his own court. He wanted to do, or at least direct, everything himself. He refused to delegate responsibility to his subordinates, scribes or notaries, as other more negligent Inquisitors often did. So the whole Pamiers Inquisition Register bears the brand of his constant intervention. This is one of the reasons why it is such an extraordinary document.

Brother Gaillard de Pomiès was his assistant (vicaire), relegated to second place by the strong personality and local prestige of the Bishop. Occasionally high-ranking Inquisitors from outside the diocese, like Bernard Gui, Jean de Beaune and the Norman Jean Duprat, would honour the weightier sessions of the ‘office’ at Pamiers with their presence. Also among the assessors was an assortment of local and regional worthies: canons, monks of all kinds, judges and jurists. At a lower level came fifteen or so notaries and scribes, there to record the proceedings but never to take part in the making of decisions. At their head was the priest-cum-scrivener Guillaume Barthe, followed by Jean Strabaud, Bataille de la Penne and a group of quill-pushers from the Comté de Foix. Sworn in last of all were the minor staff-sergeants described as ‘servitors’, messengers, jailers with their inevitable wives and, also among these lower depths, informers, some of them as distinguished as Arnaud Sicre.

A few details will suggest how our dossier was built up.1 The Inquisition court at Pamiers worked for 370 days between 1318 and 1325. These 370 days included 578 interrogations. Of these, 418 were examinations of the accused and 160 examinations of witnesses. In all, these hundreds of sessions dealt with ninety-eight cases. The court set a record for hard work in 1320, with 106 days; it worked ninety-three days in 1321, fifty-five in 1323, forty-three in 1322, forty-two in 1324, and twenty-two in 1325. The court sat mostly at Pamiers, but sometimes it met elsewhere in the Comté de Foix, according to the movements of the Bishop.

The ninety-eight cases involved 114 people, most of them heretics of the Albigensian persuasion. Out of the 114, ninety-four actually appeared. Among the group ‘troubled’ by the court were a few nobles, a few priests and some notaries, but above all an overwhelming majority of humble folk: peasants, artisans and shopkeepers on a very small scale. Out of the 114 accused or otherwise involved, forty-eight were women. The great majority, both male and female, came from the highlands of Foix, or Sabarthès, a region worked on by the propaganda of the Authié brothers. This majority from Sabarthès was made up of ninety-two people, men and women. Our village of Montaillou alone, also in Sabarthès, supplied twenty-five of the accused and provided several of the witnesses. Three more of the accused came from the village of Prades, which adjoined Montaillou itself. In all twenty-eight people, of whom each one supplied substantial and sometimes very detailed evidence, came from the tiny region of the Pays d’Aillon (Prades and Montaillou), with which our study is concerned.

Canonical procedure against an accused person was generally set off by one or several denunciations. These were followed by a summons to appear before the court at Pamiers. The summons was conveyed to the suspect, at home or in church, by the priest of the place where he lived. If the accused did not present himself voluntarily at Pamiers, the local bayle (the officer of the count or of the lord of the manor) acted as the secular arm, arresting the accused and if necessary escorting him to the chief town of the diocese. The accused’s appearance before the Bishop’s tribunal began with an oath sworn on the Gospels. It continued in the form of an unequal dialogue. Jacques Fournier asked a series of questions, pursuing various points and details. The accused would answer at length – a deposition might easily cover ten, twenty or even more big folio pages in the Register. The accused was not necessarily kept under a state of arrest throughout the trial. Between interrogations he might be shut up in one of the Bishop’s prisons in town. But he might also be let out under house arrest, bound to keep within the limits of his parish or of the diocese. When the accused was imprisoned, various pressures were brought to bear to make him confess. Apparently these pressures usually consisted not so much of torture as of excommunication or confinement either ‘strict’ or ‘very strict’ (the latter consisting of a small cell, fetters and black bread and water). In only one instance did Jacques Fournier have his victims tortured: this was in the trumped-up case which French agents made him bring against the lepers, who brought forth wild and absurd confessions about poisoning wells with powdered toads, etc. In all the other cases which provide the material of this book, the Bishop confined himself to tracking down real deviants (often minor from our point of view). The confessions are rounded out by the accuseds’ descriptions of their own daily lives. They usually corroborated each other, but when they contradicted, Fournier tried to reduce the discrepancies, asking the various prisoners for more details. What drove him on was the desire (hateful though it was in this form) to know the truth. For him, it was a matter first of detecting sinful behaviour and then of saving souls. To attain these ends he showed himself ‘pedantic as a schoolman’ and did not hesitate to engage in lengthy discussion. He spent a fortnight of his precious time convincing the Jew Baruch of the mystery of the Trinity, a week making him accept the dual nature of Christ and no less than three weeks of commentary explaining the coming of the Messiah.

When the trials were over, various penalties were inflicted: imprisonment of varying degrees of strictness, the wearing of the yellow cross, pilgrimages and confiscation of goods. Of the five guilty who ended their lives at the stake, four were Waldensians from Pamiers and the other a relapsed Albigensian, Guillaume Fort, from Montaillou.

All these procedures and interrogations were written down in a Register, two volumes of which have been lost. One of the missing volumes contained the final sentences, but these are known to us, by chance, through the compilation of Limborch.1 The surviving document now in the Vatican consists of one big folio ledger, written on parchment. This document was originally written in three stages. First, at the actual hearing of the interrogation and deposition, a scribe quickly wrote down a protocol or draft. This scribe was Guillaume Barthe, the episcopal notary, replaced in cases of absence by one of his colleagues. Then from these hasty notes the same Guillaume Barthe would compile a minute, written ‘in a paper ledger’. This ‘was submitted to the accused, who could have alterations made in it’. Finally, and at leisure, several scribes copied these ‘minuted’ texts out again on to parchment.2

The surviving volume was not entirely completed in a fair copy until after Jacques Fournier had been made Bishop of Mirepoix in 1326. This shows how anxious he was to preserve the evidence of his work as Inquisitor in Pamiers. When he became Benedict XII, the ledger followed him to his residence in Avignon and from there it passed into the Vatican Library.