You already know the common wisdom about saving money on your house. Make sure it’s insulated. Use double- or triple-paned windows. Plant shade trees. Save 1 percent on your utility bill for every degree you turn down the thermostat.

But what about some of the lesser known, newer, sneakier ways to keep and save money? That’s where this chapter comes in.

How to become a cord-cutter (cable and satellite TV)

The average American cable-TV bill is $100 a month; yours may be much higher. And that’s only the beginning; cable and satellite TV service goes up about 8 percent a year, much faster than inflation. Clearly this is an area ripe for finding some savings.

No wonder millions of people every year decide to “cut the cord”—to cancel their cable or satellite service completely.

These days, there are two less expensive ways to get your TV shows and movies. Each involves compromises, and neither is as convenient or complete as a cable subscription. But saving $1,200 a year might help to ease your pain.

Method 1: Get your TV from the Internet. Millions of people are perfectly happy to watch the TV shows and movies available from the Internet: Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Video, HBO GO, and so on.

You can watch them on a computer, tablet, or smartphone.

You can also watch them on your actual TV; if you have a fairly recent model, it probably has apps for these services built right in. (So do Blu-ray players and game consoles.) If your TV doesn’t offer Netflix, Hulu, and so on, you can always plug into it a “set-top box” like a Roku Streaming Stick ($50), Apple TV ($150), or Chromecast stick ($35; requires a smartphone as a remote control).

These services cost money, but much less than a cable-company package. For example:

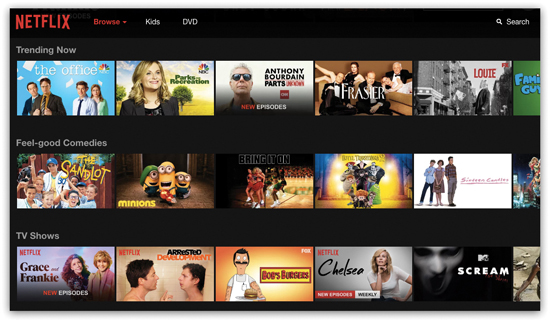

• Netflix ($8 a month) brings you thousands of old movies and some recent ones, but it also has a gigantic vault of TV shows—complete seasons that finished their run on the big networks: The Office, Saturday Night Live, Mad Men, The Walking Dead, and so on. (Netflix’s licensing deals are constantly changing, so a TV series or movie that’s here now may be gone tomorrow.)

Netflix also produces its own shows, some of which are outstanding: House of Cards, Orange Is the New Black, and so on.

• Hulu ($8 a month) offers various network shows online the day after they’re broadcast on TV, from ABC, NBC, Bravo, Fox, Comedy Central, Discovery, Nickelodeon, and a few others. Usually, only the most recent handful of episodes are available—not entire seasons, as on Netflix.

Notably absent: CBS, which offers its own subscription (read on).

• CBS All Access ($6 a month) gives you Internet access to most of the stuff broadcast on CBS.

• Sling TV ($20 a month) brings you CNN, ESPN, TNT, TBS, Disney, Food Network, ABC Family, Cartoon Network, HGTV, Lifetime, and others.

• Amazon Prime ($100 a year) offers thousands of movies, plus the TV shows produced by Amazon itself (Transparent, Mozart in the Jungle, and others).

• HBO NOW ($15 a month) gets you access to HBO’s movies, documentaries, and original series (like Game of Thrones).

• Showtime Anytime ($11 a month) is your Internet resource for Showtime’s movies, boxing matches, and original series.

• PlayStation Vue ($50 a month) is an extra-cost feature for Sony’s PlayStation game console. It’s almost like a little cable box offering CBS, NBC, CNN, Fox, TNT, BET, Comedy Central, Food, HGTV, Syfy, Travel, Animal Planet, and more.

Clearly, no one service offers everything you’d get with a cable package. In fact, once you add up all the services required for the channels you want, you may discover that sticking with cable or satellite winds up being less expensive.

Internet TV services, therefore, save money only if you don’t want all the channels of a cable or satellite package.

Method 2: Get your TV from an antenna. In the olden days, everybody got TV channels from an antenna bolted to the roof. Think of all those TV and movie scenes where the hapless suburban dad is on the roof, adjusting the antenna little by little to produce the best picture on the TV in the living room! Now that’s comedy.

Well, guess what? The TV networks still broadcast through the air, and you can still tune in to them with an antenna—for free. They come in as great-looking, full high-definition signals; they’re not compressed, degraded HD signals like the ones you get from cable and satellite. And they bring you live and local broadcasts like sports and news; none of the Internet services listed above carries live shows.

You don’t have to mount an antenna on the roof anymore, either. The best ones—the ones that tune in the greatest number of channels, from the greatest distance—are still outdoor, roof-mounted models. But plenty of HD antennas are slightly weaker indoor models, designed to sit next to the TV or, preferably, in a window.

You can also install one in your attic, which is a happy medium for many people: The antenna’s hidden, it’s easy to install, and it’s protected from the weather, but it’s higher and less wall-blocked than indoor models.

Which stations you’ll be able to get depends on where you live. Fortunately, a couple of handy websites let you know which channels you’ll get: AntennaWeb.org and TVfool.com. For best results, look this information up before you spring for a $60 antenna. (The good news: 89 percent of all U.S. households can tune in to at least five channels over the air like this.)

If you want to record shows you get over the air, you’ll need a special DVR, like one from Channel Master or TiVo.

Getting going with an HD antenna does require reading some how-to articles online and maybe dedicating an afternoon to installation. But considering the boost in video quality you’ll get and the thousands of dollars you’ll save every year (by canceling or downgrading your cable subscription), it might be worth a shot.

Savings ballpark: $1,140 a year

$1,140 = The average annual cable bill, minus $60 for an HD antenna

Free solar panels

We all know that solar power is neato. It’s free, it’s unlimited, and it’s great for the environment. Who could object to a source of power that’s as clean and natural as sunshine?

If you live in a sunny climate, you should definitely explore solar, especially since you can get the panels and the power they generate at no cost.

There are two ways to go about getting going with solar. You can buy the solar panels or rent them.

• Buy the panels. Solar panels aren’t cheap. Depending on the size of your house, you may pay $15,000 to $35,000 to buy and install them. (Loans are available to help you buy the panels.)

The good news is, though, that you can get nearly half of that back in rebates and tax incentives.

For example, the IRS will cheerfully refund 30 percent of your solar costs at tax time, thanks to the government’s Residential Renewable Energy Tax Credit. You may get further credits and refunds from your state government, local government, and utility company.

Once the panels are in place, all the power they generate is free. Your house’s value goes up.

And this is cool: You can sell electricity back to your local power companies. (They love paying you for it, because they’re required by law to generate some of their power from renewable sources, like the ones on your roof.) Every time your sunshine generates 1,000 kilowatt-hours of power, you can sell what’s called a Solar Renewable Energy Certificate (SREC) to the power company for around $200. You may be able to sell, say, 10 of those annually—a handy $2,000 a year, all thanks to Mother Nature.

Bottom line: In most cases, you’ll recoup your expenditure long before the 25-year warranty expires. Free electricity, folks!

You, however, are responsible for any maintenance or repairs that your magic free-energy panels might require. (It’s usually not much.)

• Rent the panels. Here’s where things get exciting: Companies like Sunrun and Sun City would very much like to install solar panels on your roof for free. They take care of all the permits, design, repairs, upgrades, and maintenance. They’ll even give you a phone app that lets you track how much power your panels are generating and how much money they’re saving you.

Why would those companies do something so wonderful for nothing? Are they completely nuts?

Nope. They make money from this. They collect all those rebates and incentives for installation, and they get to collect all those Solar Renewable Energy Certificates.

They also charge you for electricity. You pay the solar company instead of the electric company, in an arrangement known as a PPA (power purchase agreement).

Fortunately, you pay less than you did to the power company, and it’s a fixed rate—no surprises each month. (It’s usually allowed to creep up annually by a few percent.)

But, meanwhile, you know that you’re doing a great thing for the planet, you’re saving money, and you’ve spent $0 to get the system.

If you’re tempted by the financial and environmental juiciness of solar but can’t decide whether to buy or rent, there’s a calculator here that will tell you which approach will save you the most money: energysage.com/market/estimate. (Hint: Owning is usually the better deal, but it requires more work on your part.)

20-year savings ballpark: $65,000 (own); $27,000 (lease/PPA)

$65,000 = Electricity savings over 20 years in a sunny state + value of energy certificates sold + 3 percent home resale value increase, minus $35,000 cost of installation after rebates $27,000 = Electricity savings over 20 years for leased solar panels

Peak and off-peak power: When to run the drier

You know about the laws of supply and demand, right? Things always cost more when they’re in demand. The cost of a dozen roses doubles around Valentine’s Day. Ticket prices at Disney theme parks shoot up on Saturdays and during school holidays. The cost of a ride in an Uber car doubles or triples at rush hour.

Some prices that rise and fall with demand aren’t so obvious, however—like electricity.

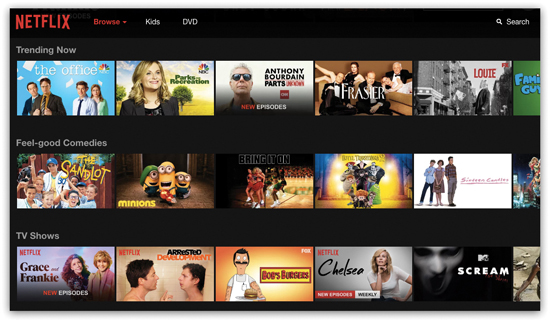

Most electric companies can sell you power at tiered prices—that is, they’re willing to charge less during periods of low demand. With these plans, electricity gets cheaper in the evening, and sometimes cheaper yet late at night, like after 9 p.m. (They charge you the most during periods of high demand, like during the workday.)

If you’re not even home during the day, you may as well take advantage of these plans and start saving money. That involves three steps:

• Find out what your utility’s time-of-day plan is. Call them, or visit their website. In most states, the plans are similar to that of PG&E (California’s utility, the country’s largest electric company): If you’re on their standard time-of-day plan, you’ll discover that the price of power jumps up by about 25 percent between 3 and 9 p.m., when most people are home.

• Switch to the time-of-day plan. For most electric companies, the time-of-day plan is one of several options; you have to request it.

• Save power and money. Some of your home’s biggest electricity gulpers run all the time (like refrigerators and water heaters), so there’s not much you can do about when they run. But other power hounds are within your control.

After heating and cooling, the biggest consumer of electricity in your home is your clothes drier. Every load of clothes you wash and dry costs you about $1 in power. Well, guess what? It’s easy enough to run your washer and drier after 9 p.m.

Same goes for your dishwasher, vacuum cleaner, dehumidifier, and electric car. If you can run or charge them after 9 p.m. (or in the morning), you save 25 percent.

Savings ballpark: $125 a year

$125 = $70 savings on running the drier (6.7 kW per load, two loads a week, 10 cents off-peak) + $29 savings on washing machine (2.75 kW per load, two loads a week, 10 cents offpeak) + 5 kW for miscellaneous other devices off-peak

The LED lightbulb revolution

What is wrong with people? If they had any idea how great LED lightbulbs are, they’d never buy any other kind of bulb again.

LED bulbs turn on to full brightness instantly. They remain cool to the touch. They’re hard to break and safety-coated if they do. They work in the cold and in high humidity. They put out negligible heat.

Above all—since you’ve gone to the trouble of picking up a book about money—LED bulbs save you money, hand over fist. In two ways:

• 70 percent lower lighting bill. Incandescent bulbs are incredibly inefficient; they burn up 90 percent of their energy as heat, not light. No wonder an LED bulb needs only 30 percent as much juice. In other words, LED bulbs mean lower utility bills and a much smaller carbon footprint for your home.

• 20 times longer life. LED bulbs last 20 years or more. Yes, they cost more than traditional bulbs: maybe $5 for a 100-watt equivalent, vs. $1 for an incandescent bulb. But practically speaking, you’ll buy a new house before you have to buy a new LED bulb.

LED bulbs also contain electronics, a fact that has sent clever inventors into overdrive. You can buy bulbs that change color, that contain wireless speakers, that turn themselves on and off on a schedule automatically. And you can control it all with a smartphone app.

The old concerns about LED bulbs’ color and dimmability have long since been addressed. You can now buy them at whatever “color temperature” (color tone) you want, and the package lets you know which ones are dimmable.

The sooner you replace your house’s bulbs with LED, the sooner you’ll start saving money—and seeing better.

10-year savings ballpark: $900 in electricity, $60 in bulb replacements

$900 = 10-year electricity savings for 12 bulbs ($11 per year per incandescent bulb running four hours daily, with electricity at 11 cents per kWh, minus $3.50 for an LED bulb) $60 = 10-year bulb savings (a dozen incandescents every year at $1 each, minus one set of 12 $5 LED bulbs)

Reusable gift wrap: Like money in your bank

Must be nice to be in the gift-wrap business. You’re selling rolls of very cheap paper at a satisfying markup. It’s made to be used only once and then ripped up and thrown away. At that point, people have only one choice: to buy more.

There are three annoying aspects to this cycle. First, you have to keep buying this stuff. Second, it’s a fussy, time-consuming job to use it—to wrap up the presents with it. Third, it’s not always a joyride for the recipient to open the package (“Can you hand me the scissors?”).

Why do we wrap gifts, anyway? To conceal what’s inside until the big day of opening, of course. To preserve the surprise, preferably with an eye-catching and festive look.

So here’s the idea: Instead of buying rolls of gift-wrap paper every year, buy a set of gift-wrap bags. They look just like wrapping paper (they’re printed with the same cheerful decorative patterns), but they’re drawstring bags. Draw-ribbon bags, actually. You can get about 60 of them, in sizes from tiny to enormous, for $12.

Suddenly, your wrapping job is nearly instantaneous—you just drop the present into the bag and draw it tight with the ribbon handles. The result looks just like a regular wrapped gift, but it’s much easier to open.

And here’s the beautiful part: You don’t throw it away. You reuse the same 60 bags, year after year. You’re doing a good deed for your time, your recipients’ time, the environment—and your wallet.

Savings ballpark: $15 a year

$15 = Three rolls of wrapping paper at $5 each, enough to cover eight gifts for four people annually

Dry your hands the 1890s way

According to legend, the Scott Paper Co. of Philadelphia invented paper towels by accident.

At the time, Scott was in the business of making toilet paper. But then, one fateful day in 1907, a railroad car arrived at the plant, full of paper that was too thick to serve as T.P.

Co-founder Arthur Scott didn’t want to throw away all that raw material. So he cut it into squares and sold it to hotels and restaurants as a hygienic, disposable alternative to cloth towels in public restrooms.

To this day, paper towels are great for mopping up spills that are too gross for wiping up with a sponge—pet messes, for example.

They are not, however, any better than cloth hand towels for drying your hands.

The old argument against hand towels—the one that Arthur Scott had in mind—is that they spread germs from one hand-wiper to another. But these days, who needs to dry their hands? People who have just washed them! Their hands are already clean!

The bottom line: If you learn to dry your hands on a hand towel after washing them, rather than ripping off a square of paper towel every time, you’ll help both your bank account and the environment.

Savings ballpark: $85 a year

$85 = One roll of paper towels saved each week at $1.75 per roll, minus $6 Walmart hand-towel set

Free fine art for your fine walls

Fine art is usually considered a wealthy person’s game. A handsome original piece of art might cost hundreds or thousands of dollars, plus $300 to get it custom-framed.

There is, however, an ingenious way to get stunning artwork for nothing—and to custom-frame it for one-tenth as much as you’d expect.

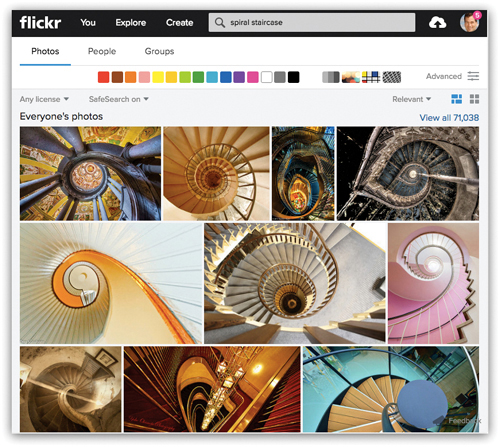

• Step 1: Get the free art. Visit Flickr.com, one of the Internet’s largest repositories for spectacular photography. Search for the kind of imagery you’re looking for: landscape, cityscape, trees, sunset, abstract, whatever. (Bonus tip: Search spiral staircases. Those make really cool art, especially in black and white.)

The search will unearth thousands of images that match your description. Now you want to find the free ones—the ones whose creators have already given permission for anyone to use their work in any way.

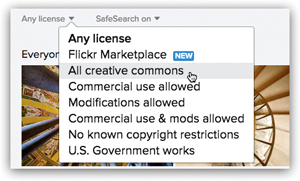

To do that, click the “Any license” pop-up menu and choose “All creative commons.” Now you’re looking at pictures that you’re free to download and print.

(By the way: If you see an image you love that instead says “All rights reserved,” feel free to email the photographer and explain what you have in mind. Offer something—maybe $20. As long as you’re not using that picture for commercial use, like in an advertisement, you’ll usually get an OK.)

Click the photo and inspect it; make sure that its resolution will be high enough for the print size you want. If its dimensions are in the mid-thousands (for example, 5472 × 2648 pixels), you’ll be in good shape.

Download the file.

• Step 2: Order the framed print. A number of websites offer professional printing and framing of any picture you send them. At mpix.com, for example, you can upload your photo, choose a frame type, specify a final size, and order the whole thing. They’ll print the photo on gorgeous paper and frame it for you in a couple of days. An 8-by-10-inch photo becomes an 11½-by-13½-inch framed print—and costs about $26.

The final results look exactly like the most professional, high-end photography and framing you could possibly buy. Nobody will ever know that your grand total expenditure was 26 bucks.

Savings ballpark: $474 per framed print

$474 = $200 commercial artwork, custom-framed for $300, minus the cost of a Flickr print, printed and framed for $26

Cool breeze on, air conditioner off

The air conditioner is a marvel, isn’t it? Our sweltering ancestors, toiling indoors in the steamy summer heat, would have fallen down and worshipped it as a god.

The air conditioner is also, however, a massive power hog. During periods of great summer hotness, its appetite can account for half your electric bill. No other appliance comes even close. (Air conditioners alone consume 5 percent of all the electricity in America.)

Exactly how much it costs to run the AC depends on the size of your house, the power of the unit, the temperature and humidity outside, the setting you’ve dialed up, the current price of electricity, and so on. But just for kicks, here’s a typical example: A central air conditioner using 900 kilowatt-hours a month will cost you $120 a month. A window air conditioner running six hours a day (270 kilowatt-hours) will cost $35 a month.

If you’re not the only one at home—if you’re sharing the space with other hot people—then running the AC makes sense.

But if it’s just you sitting at a desk, or you and another person sleeping in a bed, then a fan is an enormous money saver. It can keep you comfortable, but it costs you next to nothing. Maybe a penny an hour.

(A fan cools you in two ways: By pushing your own body heat away from your skin and by evaporating the sweat off your skin, which has a cooling effect.)

A ceiling fan set on high, running for 12 hours a day, will cost you maybe $3.50 a month—that’s one-tenth as much as a window air conditioner, or 3 percent as much as central air. A desk fan, of course, saves even more.

And when it’s too hot for a fan to do the job—when the room air is above 85 degrees, for example—use the fan and the air conditioner. You’ll be able to set the AC to a higher temp, running it less, and rely on the fan to make up the difference.

Savings ballpark: $226 a year

$226 = Central air at $120 per month, minus ceiling fan at $3.50 per month, running four months a year and reducing central air use by half

The embarrassing truth about programmable thermostats

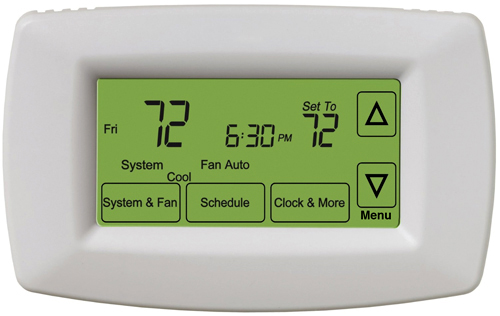

You don’t need an engineering degree to see how a programmable thermostat saves money.

A manual, dumb thermostat wastes an insane amount of energy by heating or cooling your house when there’s nobody in it. That makes about as much sense as running an empty oven. Or mowing a parking lot.

A programmable thermostat, of course, is one that you set to run during specific times of day. It warms or cools the house only when you’re there and saves money the rest of the time.

But here’s an astonishing statistic: Only 30 percent of U.S. thermostats are programmable. And of those, fewer than half are actually programmed! According to a Berkeley National Laboratory study, 53 percent of us just set the thing to one temperature and then hit Hold!

We turn our smart thermostats into dumb ones and pointlessly burn hundreds of dollars a year.

Yes, that’s appalling, but you can’t blame the homeowners. First of all, most of us don’t choose our thermostats; they are already on the wall when we move in.

Worse, the thermostats themselves are about as easy to operate as a Boeing 747. Quick: What’s the difference between Temporary Override, Timed Hold, Permanent Hold, Permanent Override, and Away modes?

Most thermostats are just too hard to figure out. And the manuals probably disappeared sometime around the Reagan administration.

Still, fixing the thermostat situation in your home is hugely important. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, programming your thermostat correctly can save 15 percent on your heating bill. In an average home, that’s a savings of $100 (natural gas) to $315 (oil) every winter. In the summer, you’ll save another $75 or so on air conditioning.

All right. So let’s suppose you have a manual thermostat, or a programmable one that’s too hard to figure out. Take a deep breath, set aside a Saturday, and proceed like this:

• If you have a programmable thermostat but lost the manual: Somewhere on that thing, you’ll find a sticker or a panel that tells you the brand and model. Go to Google and search for its user guide. Type, for example, Honeywell RTH6450D1009 manual.

Sure enough: You’ll find that the instruction manual is available to read online, or to download and print. Invite a neighborhood teenager to stand by your side, if necessary, and force yourself to program that thermostat.

Set it to allow the house to cool down (in winter) or heat up (in summer) during the hours when nobody’s home—and when you’re asleep on a different floor.

• If you don’t have a programmable thermostat: Get one. They cost as little as $25. (If you’re handy with a screwdriver and can follow instructions online, you can install it yourself. Otherwise, factor in an electrician visit.)

Anything you buy today will be easier to use than the user-hostile designs of 10 years ago. But if you have a smartphone (like an iPhone or an Android phone), you’ll get particular joy out of a Nest thermostat or Honeywell Lyric thermostat. The Nest programs itself by learning the patterns of your daily comings and goings; the Lyric detects when you’re approaching or leaving home (from the GPS of your phone) and heats or cools the house accordingly. You can operate either one by remote control, using an app on your phone.

These amazing thermostats cost $200 or $240—which you’ll recoup in just over a year.

Savings ballpark: $280 a year

$280 = Annual savings in heat and cooling by programming the thermostat—a nice, even number between $175 (savings if you have gas heat) and $390 (oil heat)

Instructions for boiling water

Time for tea! Or soup! Or pasta! Or lobster!

But what’s the best way to boil the water?

You could put the kettle on the stove. You could use an electric kettle that doesn’t require a stove. You could microwave a cup of water. You could start with hot water from your faucet and heat it up from there.

Here’s the answer, as determined by the number crunchers at TreeHugger.com:

• Worst way: the stove. A lot of heat gets wasted as it travels from the flames (or electric coil) to the metal of the kettle or pot, and from there to the water. You’re also heating a lot of air around the pot. Time: 5 minutes. Efficiency: 30 percent.

• Better: the microwave. The nice part here is that you’re heating only the water and the mug. (You waste some power by heating the mug, but of course the mug will then keep your water hot longer.) Time: 3 minutes. Efficiency: 47 percent.

• Best: an electric kettle. The heating element is in direct contact with the water, so you’re not heating anything that you don’t need to heat. And the thing shuts off when your water is boiling. Time: 2 minutes. Efficiency: 81 percent.

Starting with hot water from your faucet doesn’t really count for much either way; you’ve already used power to heat it up.

Savings ballpark: $2.50 a year + deep satisfaction

$2.50 = 0.07 kWh of electricity saved per boiling (0.11 kWh for the stove, 0.04 kWh for the kettle) × 12 cents per kWh average electricity price × two boilings a day × 365

The “It takes more energy to reheat a room” myth: Demolished

When it comes time to program your thermostat, you may be haunted by the memory of some friend or parent saying: “It’s cheaper to keep the heat on all night! Because if you let the downstairs get cold, it takes more energy to reheat it in the morning.”

As it turns out, that’s false. It takes less energy to bring a cold room back up to 68 degrees than it does to keep it there all night.

The “heat the house faster” myth: Demolished

Surely you’ve seen them: people who think they can get the house warmed up faster if they set the temp beyond the comfort point. In other words, you like 68 degrees in winter, but you come downstairs to a 64-degree room—so you set the thermostat to 85 to make it heat up faster.

In fact, you’ll only waste power and money that way. Heating is either on or off, like a light switch. The room warms up at the same rate, whether you set the thermostat to 68, 100, or 5,000 degrees.

So set it to 68 and be patient.

(All of this applies equally to air conditioning. And the same principle also applies in your car.)

The replacement-window myth: Demolished

The ads aren’t shy. They make it explicitly clear that if you replace old, drafty windows with modern, energy-efficient ones, you’ll save a lot of energy and money.

Well, that’s true. But window replacements aren’t cheap; upgrading all your windows can cost thousands of dollars.

Replacing your windows makes sense if you’re aiming to solve environmental, cosmetic, or draftiness problems. If you’re planning to replace windows anyway, definitely get high-efficiency ones.

But if you’re considering making that move purely as a financial play, you may be making a mistake. According to energy experts, there are many less expensive moves you should make first.

For example, you’ll get a giant energy savings just by sealing gaps around doors, windows, pipe cutouts, and other transitions to the outdoors. (A home energy checkup, or energy audit, is often worthwhile; read on.)

Savings ballpark: $7,000

$7,000 = Cost of 15 vinyl-clad windows, installed, at $500 each, minus $500 for an energy audit

The light-switch myth: Demolished

Here’s something else some family member or co-worker might have mentioned to you: “Stop turning the light off all the time. It uses more energy to turn it off and on all the time than to just leave it on.”

Turns out that’s not true. No matter what kind of bulb, turning the light off whenever possible saves energy—and money.

In praise of the home energy audit

Your house is equipped with big machines that pump heated or cooled air into its rooms, but the house itself is a leaky vessel. Usually, anywhere from 5 to 30 percent of that heated or cooled air leaks out of the house.

In other words, unless your house was built recently, the odds are very good that you’re spending a huge amount to heat or cool the outdoors. You’re ensuring comfort for the birds and the bees, along with your family.

Identifying the cracks, holes, and leaky spots is one of the primary goals of an energy audit or energy checkup. If heating and cooling were minor expenses in your life, this kind of headache wouldn’t be worth it. But home energy is a huge expense—and an audit is worth it.

You can do the inspection yourself, if you’ve got more time than money. Your own government has posted a handy guide at energy.gov/energysaver/do-it-yourself-home-energy-audits.

That page tells you what to look for: gaps along the baseboards and wall joints, missing insulation, and so on.

If you’re willing to invest a few hundred bucks, though, it’s much better to hire a professional to do this job, someone who’s equipped with detection equipment like infrared scanners to spot the heat leaks. In theory, you’ll recoup the expense of the energy audit fairly quickly once your leaky house is patched up.

To find an energy auditor, you have a few options:

• Visit resnet.us/directory/search.

• Ask your electric or gas company. They can often recommend local firms—or even offer a discounted or free audit themselves.

• Ask the energy or sustainability office for your town or state. (Yes, you have one. Google cleveland energy office, for example.)

Savings ballpark: $1,000 a year

$1,000 = Typical annual heating, cooling, and electric savings to result from energy-audit findings

Never get ripped off on home services again

You need a painter, electrician, plumber, architect, or construction contractor. You want someone to mow your lawn, clean your gutters, or babysit your kid. You wonder which is the best electricity supplier, Internet provider, or cable TV company. Where do you start?

All these service industries are teeming with companies that might disappoint you. And those services are expensive, so you probably want to avoid hiring a deadbeat.

Where do you go for such local advice? Here are three ways to find it:

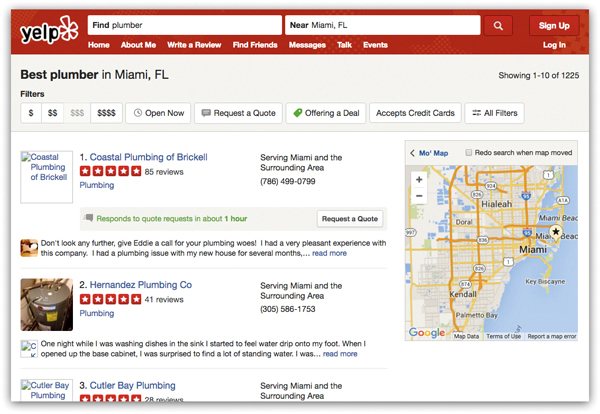

• Yelp.com is the Internet’s biggest database of reviews for local businesses—20 million of them. Almost every service, store, and restaurant gets reviewed by actual customers and gets a star rating for easy comparison. And Yelp is free to everyone.

The only downside of searching Yelp is that, because it’s so free and open, some of these businesses try to game the system. They post positive reviews about themselves under fake names, for example. Yelp has a huge fraud team (and clever software algorithms) dedicated to weeding out such phonies, but they can’t catch them all; you have to use your own judgment.

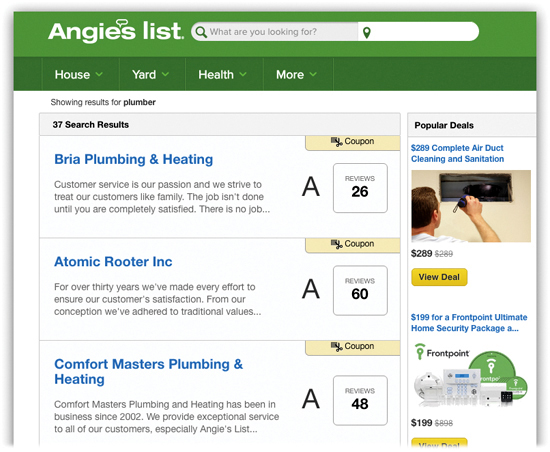

• Angie’s List. From its founding in 1995, this massive database of customer reviews and ratings (AngiesList.com) was a subscription-only service costing around $30 a year. Now, happily, it’s free to everyone.

This site is better controlled, organized, and cleaned up than Yelp; customers rate each service on its professionalism, price, quality, and responsiveness and then give it a grade, A to F.

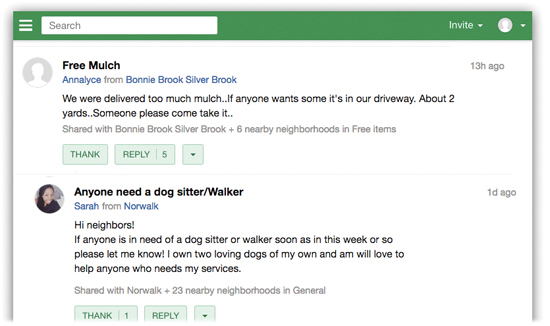

• Nextdoor.com. Here’s a fantastic free site that’s been hiding right under your nose. Nextdoor is a hyper-local bulletin board—that is, you’re hearing from people who live not just in your town, but on your own block.

The posts include plenty of “Has anyone seen my dog?” and “Anyone want an old couch?” messages, but there are also a lot of “Who knows of a good snow-plowing service?” and “Anyone know a reasonably priced mechanic?” posts. Almost always, you get prompt responses from people who’ve been down your road before.

Savings ballpark: Months of headache

How not to get ripped off on Valentine’s Day roses

Florists aren’t crazy. They know perfectly well when everyone in the world is going to want red roses: February 14. Valentine’s Day.

No wonder the price of red roses spikes dramatically during that week. It usually doubles.

But information is money—and here’s the information you need to fight back.

• Buy them before the spike. Roses usually last five days before they wilt. But they can last much longer if you’re smart.

Trim their stems when they arrive. Change the water every couple of days. Keep them away from heat and windows.

Finally, the big one: Put the stems in sugar water (6 teaspoons of sugar in 32 ounces of water). That simple act gives roses three more days of life, meaning that you can buy them as early as February 9 and avoid the red-rose rush hour.

But the real miracle drug is silver nitrate—a chemical related to what people used to use to develop film. You can buy a bottle for $20 online. Add a few drops to the roses’ water, and you can extend their life another four days. (Lawyers’ note: Don’t drink or touch silver nitrate.)

• Choose other colors. Red roses cost around $20 more per dozen than pink, yellow, or orange ones. Would your beloved be insulted if the roses weren’t red?

• Go for the bouquet. Order a bouquet that includes roses and other flowers. For the price of a dozen roses, you can get a truly spectacular spring bouquet that actually provides a much stronger, lovelier fragrance than commercial roses alone.

• Buy the roses online. Services like ProFlowers.com and TheBouqs.com sell roses at lower prices than local shops do, in part because they send the roses directly from the rose farms.

In fact, if you’re willing to accept delivery a few days before February 14, you can save as much as 25 percent.

Bonus tip: It’s easy to find coupon codes for online florists; do a quick search at RetailMeNot.com (here).

Finally, of course, there’s the nuclear option: Buy your roses on February 15, the day after Valentine’s Day. You lose some romance points, but you get gorgeous roses dirt cheap—and you save enough to take your beloved out to a really nice dinner.

Savings ballpark: $40 a year

$40 = Savings on 12 long-stemmed roses delivered on February 9 or 15, instead of February 14