We love us our gadgets. They keep us entertained, keep us in touch, keep us informed.

They also keep us paying through the nose. Cable TV, Internet, and cell phone service—and the electronics we use to access them—have come to represent an enormous chunk of our expenditures these days.

They are, therefore, ripe for inspection by the ardent money-saver.

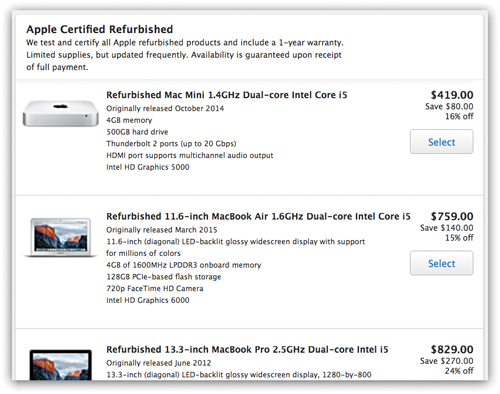

Where to buy new tech for cheap

Every computer manufacturer’s website offers a listing of refurbished machines at huge discounts. You’ll find special pages listing this equipment on the websites of Apple, Dell, HP, and so on. (To find these special pages, use Google to search, for example, for refurbished Macs or refurbished Dell.)

Now, your first instinct might be to exclaim: “Eww! I don’t want some used computer, full of cat hair and baby drool!”

Ah, but in this case, the “refurbished” computers aren’t what you’d expect. They’re brand-new. They haven’t been used. They’ve been inspected even more thoroughly than new machines. And they have the same warranty.

Usually, they were bought and then returned for some reason, sometimes without even being opened.

For your willingness to buy something that’s been shipped and returned, you’re treated to substantial price cuts. Keep this trick in mind the next time you’re in the market for a new laptop, tablet, or whatever.

Savings ballpark: $250

$250 = Savings on a 13-inch MacBook Air, $1,200 new, offered at $950 refurbished

Cheaper cable TV through creative cord-cutting calls

Cord-cutting. It’s happening all over the country, and it’s freaking out the cable companies.

Cord-cutting means canceling your TV service. To paraphrase millions of people everywhere: “Why should I pay $180 a month for a bunch of channels I never watch? I can get the good shows directly from the Internet—Netflix, Hulu, iTunes, and so on.” (See here for more on cord-cutting.)

The thing is, the cable/satellite companies spent a lot of money on marketing to get you to sign up in the first place—at least $1,000 per customer. And in this day of Internet TV, it’s getting harder and harder to sign up new customers. So they’ll bend over backward, financially speaking, to stop you from canceling.

So here’s what you do:

• Call your cable or satellite company. Tell the customer service rep that you’d like to cancel your service.

(Note: If you don’t have the nerve to bluff like this, simply say that you want to cut your service down to the most basic plan. That way, you’re not bluffing. If it actually comes to that, and they change your plan, no harm done. Just call up the next day and restore your higher-priced plan.)

(Another note: If you don’t even have enough nerve to do that, you can often have good luck just calling and asking for a better deal—without threatening to quit or downgrade. Especially if you’ve been a customer for a long time, you might be surprised at how willing the cable company might be to help you out. —James Dietsch)

• They’ll ask you why you want to cancel. Tell them you’ve decided to cut the cord: You’re happy getting your TV from Netflix and Hulu.

• The rep will probably transfer you to the Customer Retention Group or a customer loyalty agent. This is a special department that exists solely to stop people from canceling.

• The retention specialist will offer to lower your bill if you’re willing to change your mind about canceling.

• The more you insist on canceling anyway, the better the offer.

If you’ve read about a better deal from a rival cable or satellite company, by all means mention what it is. Insist that you’ll remain a customer only if the rep can match that deal.

What kind of deal will you get? It depends on your persistence and what kind of plan you’re already on. Maybe you’ll get $40 a month knocked off your bill. Or, if you already pay for TV and Internet (or TV, Internet, and phone service) from a single company, the deal might be so good that you get the TV service for almost nothing.

Savings ballpark: $480 a year

$480 = $40 negotiated discount from your monthly bill

Buy your own cable box, save hundreds

As though the cable companies weren’t already milking you dry with the cost of the TV service, they’re also charging you about $235 a year to rent the cable box (the one that changes channels and connects to your TV). It’s about $7.50 a month per box. Most people have more than one TV, so they rent more than one cable box.

If your cable box also includes a video recorder (DVR), you’re paying even more. Now you’re talking $300 or $400 a year.

As it turns out, it’s 100 percent OK to supply your own cable box or DVR and eliminate those expenses!

The best of the best is the TiVo, which is both a cable box and a DVR. (Some TiVo models require you to pay a monthly fee [$15] or a one-time, lifetime service payment [$250].)

But at sites like CableBoxandModem.com, you can buy your own replacement cable box for $120 (pays for itself in 16 months) or a combination cable box/DVR for $200 (pays for itself in eight months—no service fees).

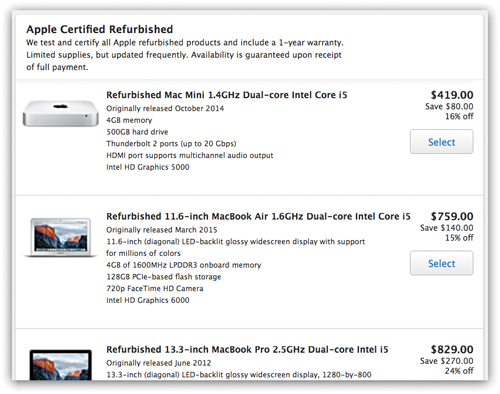

Now, part of the purpose of a cable box is security; the cable company wants to make sure you’re actually paying for all the channels you’re receiving. If you supply your own cable box, how will your cable company know it’s you?

Because you’ll slip a CableCard into it. You can buy a CableCard for under $5 from the cable company, preprogrammed with your account information, and slip it into the back of the box you’ve bought.

(By the way: When you call the cable company to request that they send you a CableCard, don’t let them play dumb. They are legally obligated to sell you one and even help you install it.)

Savings ballpark: $192 a year

$192 = Savings of $10 a month for each of two cable boxes, minus rental of two CableCards for $2 per month

Don’t pay for cable while you’re away

If you go away for vacation—or if you spend your time in two different homes during the year—why should you have to pay for cable TV or satellite service while you’re away? You shouldn’t!

Unbeknownst to almost everybody, the cable and satellite companies offer vacation-suspension plans. All you have to do is call to let them know when you’re leaving and when you’re returning—and then stop paying while you’re away!

The plans may change over time, but here are some examples:

• Comcast Xfinity (800-934-6489). How long can you suspend? Three to nine months. How often? Once a year. How much does it cost? $7 a month each for TV and Internet. Notes: The program, called Vacation Hold, is available only in Indiana, Michigan, Chicago, and Florida.

• Time Warner (800-892-4357). How long can you suspend? Two to 10 months. How often? Once a year. How much does it cost? $5 a month.

• Dish (844-394-6568). How long can you suspend? Two to nine months. How often? Once a year. How much does it cost? $5 a month.

• DirecTV (800-507-2716). How long can you suspend? One to six months. How often? Twice a year. How much does it cost? No charge.

• AT&T U-verse TV (800-288-2020). How long can you suspend? One to two months. How often? Once a year. How much does it cost? $17 a month.

• Verizon Fios (800-300-4184). How long can you suspend? One to nine months. How often? As often as you like. How much does it cost? $40 per suspension.

• Cox Communications (866-961-0027). How long can you suspend? One month to forever. How often? Twice a year. How much does it cost? $20 a month.

• Charter Spectrum (800-398-6192). How long can you suspend? Up to six months. How often? Once a year. How much does it cost? $12 to $15 a month per service (TV, Internet, phone).

Savings ballpark: $285 a year

$285 = Average U.S. $100 cable bill suspended for three months, minus $5 monthly fee

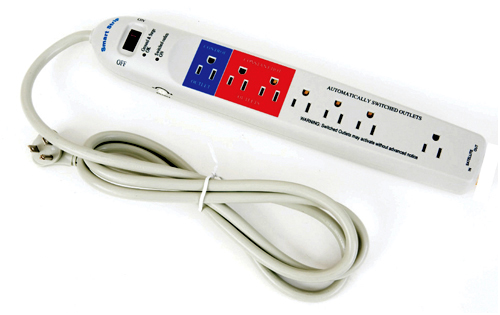

Supply your own cable modem

It’s bad enough that your cable company makes you rent the cable box that plugs into your TV. At this moment, you’re also paying to rent your cable modem, the gadget that brings high-speed Internet into your house. This time, the damage is about $10 a month, forever.

Once again, there’s no reason for you to keep paying! Buy your own cable modem for $100, return the one you’ve been renting, and boom: a $120-a-year savings.

Before you shop for your own modem, make sure you’ve found one that works with your cable company. Do a Google search for, for example, comcast compatible modems.

Once you’ve ordered the modem, call up the cable company and let them know you’ve bought your own (which is perfectly OK and increasingly common). They’ll walk you through setting it up. They’ll give you the address of a return center for shipping back the one you’ve been renting.

And then they’ll take that $10 fee off your monthly bill!

Savings ballpark: $120 a year

$120 = Savings of $10-per-month cable-modem rental every year

Driving a stake through vampire power

We leave all kinds of things plugged in when we’re not using them: microwaves, game consoles, TVs, cell phone chargers, computers, cable modems, cable boxes, garage-door openers. Unfortunately, all those things keep using electricity, even when they’re in idle, standby, or sleep mode. They stay on so that their clocks or status gauges remain up to date, so that they turn on quickly when we want them, or so that they can remain “listening” for signals from a remote control.

The trickle of juice they keep using is called vampire power. (Why? Because vampires are invisible and they suck the life out of us. Get it?)

American households spend about $19 billion a year on vampire power. Your share: $165 a year on average, $400 a year if you have a high-tech kind of house.

A big part of the problem is that many household appliances that were once purely mechanical now have screens, Internet connections, and other digital elements: washers, driers, toasters, microwaves, refrigerators, and so on. So they consume a trickle of power all the time.

In any case, vampire power costs you, and it costs the earth. America’s vampire power alone consumes the output equivalent of 50 large power plants.

According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, here are the steps you can take to fight back:

• Unplug things that don’t need to be on, like the TV, cable box, and DVR in the guest room, the furnace in the summertime, or a second refrigerator. (If you can get rid of the second fridge altogether, that’s even better; older fridges, like the ones people keep in their garages or basements, use old, juice-guzzling technology.)

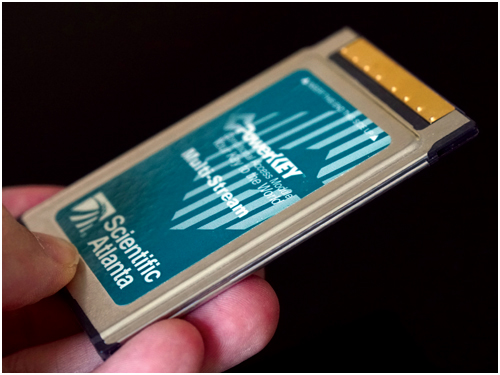

• Use smart power strips. You can plug all your TV stuff (set, speakers, Blu-ray player) into a single strip, and turn them on or off all at once when you need them. Same thing with your computer system: PC, monitor, printer, speakers.

In fact, because so many people are trying to clamp down on vampire power, you can now buy smart power strips. Some use a master-slave arrangement: If you turn off the main appliance (like the computer), then the associated outlets (like the monitor and printer) also cut power.

To find these strips, do a Google search for smart power strip.

• Automatically limit the charging time. For about $6.50, you can get a Belkin Conserve Socket (or one of its rivals). It cuts off power automatically after 30 minutes, three hours, or six hours—perfect for phones, tablets, laptops, and other things that you plug in to recharge. There’s really no point in letting them suck up juice after they’re fully charged; in fact, most manufacturers suggest not leaving them plugged in all the time.

• Use timed outlets. Some power strips (and power-outlet adapters) are programmable. You can set them up to cut power based on time of day (do a Google search for timed power strip), which is perfect for gadgets like water recirculation pumps, coffeemakers, towel heaters, and heated bathroom floors.

• Turn off the instant-on feature. Most TVs are on even when they’re off. They remain in “instant on” mode so that they’ll pop right to life when you hit the On button on the remote. Same thing for game consoles.

The thing is, you can turn that feature off on many models (burrow into the settings). If you don’t use your TV or console every day, it might be worth the trade-off: You’ll have to wait a minute for the thing to warm up when you turn it on, but you won’t be guzzling juice all day and night.

Savings ballpark: $165 a year

$165 = The per-household amount of the $19 billion a year Americans spend on vampire power, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council

The Great Digital-Cable Scam

For decades, audio nuts have debated the value of buying absurdly expensive cables to connect their stereo components. Surely gold-tipped cables must conduct sound more purely and authentically than cables made of more ordinary stuff.

Well, no book author would be wise to step onto that battleground. Judging sound is a black art, highly subjective—a world where there’s no clear right or wrong.

Digital cables, however, are a different story.

These days, the cable that carries audio and video between TV components is called HDMI. It’s the one that connects TVs to Blu-ray players, cable boxes, Apple TVs, TiVos, and other gear.

The makers of cables have eagerly jumped into the market with the same marketing message they’ve always used for audio. They want you to believe that fancy gold- or even platinum-tipped HDMI cables will give you better picture and sound. They hope to exploit the same sort of uncertainty that’s allowed them to profit from audio cables for years.

Unfortunately for them, there is no uncertainty this time. An HDMI cable carries nothing but digital signals—1’s and 0’s, the language of computers. There’s no such thing as an HDMI cable whose signal looks a little better than another; an HDMI cable either works completely or doesn’t work at all.

Therefore, a $7 HDMI cable you buy online is just as good as an $80 HDMI cable from your local TV store.

Savings ballpark: $146

$146 = Savings of $73 off each of two gold-tipped HDMI cables

Cell phone service for $8 a month—or even free

What you’re currently paying for cell phone service is probably around $75 a month; that’s the average American cell phone bill. Actually, nearly half of us pay over $100 a month.

Well, how’d you like to pay less than one-twelfth that much? Or even get your service for nothing?

You can—by using a prepaid plan. Instead of paying the carrier at the end of the month, you buy minutes and data before you use them. (It’s really not such a strange setup; your car is on a prepaid plan, too. You pay for the gas before you use it.)

In the beginning, prepaid phones came from little companies that, behind the scenes, bought and resold cellular bandwidth from the Big Four (Verizon, AT&T, Sprint, and T-Mobile). You might have been paying a company called Red Pocket, but behind the scenes, it was AT&T carrying your calls and getting you online.

These days, the Big Four have bought up a lot of those little companies, to capitalize on the growing popularity of prepaid plans. You may have heard of Cricket Wireless (owned by AT&T), Boost Mobile and Virgin Mobile USA (Sprint), GoSmart Mobile and MetroPCS (T-Mobile), or Page Plus Cellular (Verizon). Each Big Four company also offers prepaid plans under its own name.

In addition to saving you all kinds of money, prepaid phones have a bunch of other advantages. There’s no contract; you can stop and start service whenever you like. There’s no monthly bill. There’s no “activation fee,” that stupid $35 that the Big Four charge every time you start service. There’s no credit check or age limit, either, which is what makes prepaid phones useful to con men and con children.

So how much can you save by paying in advance? A ton. The exact prices and offerings will have changed by the time you reach the end of this sentence, but the following examples are typical.

Remember: The point of comparison is what the average American spends on cell phone service a month—$75—on the traditional (postpaid) plan.

• $100 a month (Boost Mobile) is all it costs for unlimited calling, texting, and data on four family phones. Each gets 1.5 gigabytes of high-speed data; after that, the speed slows down unless you pay for more of the high-speed stuff. (It winds up being too slow for video streaming, but fine for email and web surfing.) Handy bonus: Even if you stop paying, you can still receive incoming calls and texts for two months, free.

• $42.50 a month (Straight Talk Wireless/Walmart) gives you unlimited calling, texting, and Internet use (data) on a smartphone. The first 5 gigabytes each month are high speed; after you’ve used that, the service slows down.

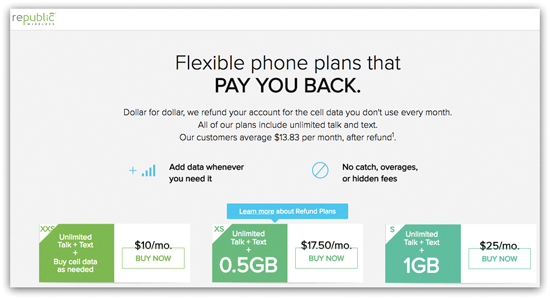

• $25 a month (Republic Wireless) gets you unlimited calling and texting on a smartphone and 1 gigabyte of data. But it gets better: If you don’t use that whole gigabyte, you actually get refunded for the amount you didn’t use. Republic’s average customer winds up paying $13.82 a month. (Republic’s phones make phone calls over Wi-Fi, when it’s available, instead of the cellular network, which is how they keep the plan prices so low.)

• $19 a month (CellNuvo) gets you 5,000 “credits” a month to use on a smartphone. You can spend these credits as any proportion of text messages (one credit each), calling minutes (10 each), or megabytes of data (10 each). If you do that stuff in a Wi-Fi hotspot, you don’t use up any credits.

You can get more credits for free by watching an ad or filling out a survey.

Also: If, at the end of a month, you haven’t used any credits (by sticking to Wi-Fi, for example), you’re not billed the $19 for the following month.

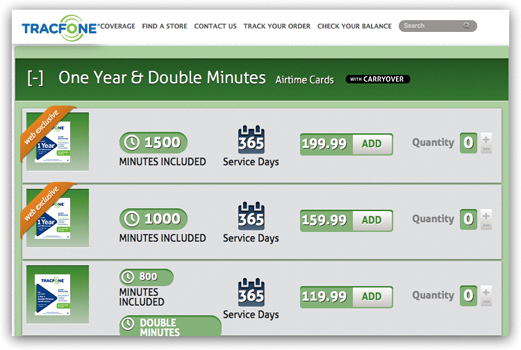

• $16.60 a month (TracFone), paid as $200 a year in advance, gets you 1,500 calling minutes or text messages to use all year long—about two hours of yakking a month. (A text message costs the same as one minute of talking.)

• $9 a month (TracFone) gets you 30 minutes of calls (non-smartphone). As long as you keep the service, unused minutes roll over month to month. If you don’t sign up for auto-renewal every month, the service is $1 more.

• $8.33 a month (TracFone) is the price if you pay for a whole year in advance ($100). It gets you 400 calling minutes or text messages to use during the year—a good safety net for the infrequent caller.

• Free (CellNuvo). This setup, called the Infinite plan, will take some explaining. But, yes, it’s possible to have a smartphone with free service.

This company starts you out with 2,500 free “credits,” which you can spend on calls, texts, or data as described already (see “$19 a month”). You can refill your credits infinitely by watching ads, taking surveys, or accepting a “thank-you” text from the company. Or, if you’re impatient, you can buy 2,500 more credits for $10. Either way, you have to scrape up 2,500 new credits each month to keep your service alive.

There are also some taxes and a $25 activation fee. But overall, if you’re a person with more time than money, CellNuvo is the closest thing you’ll ever see to a free cell phone.

Note that these prices don’t include the phone itself. Phones might cost $0 for a very simple phone, $20 for a basic Android smartphone, or $600 for a new iPhone or Samsung Galaxy. Usually, you can supply your own phone—maybe one you’ve snapped up used from someone on eBay or Craigslist.

So where do you buy the “gas” for your prepaid phone? You can buy a phone card for your brand in gas stations, drugstores, and so on—or you can just pay on their website. Either way, you get a code that you type or scan into the phone.

The bottom line: Prepaid phones are one of the biggest money-saving secrets left on earth.

Savings ballpark: $1,120 a year per person

$1,120 = Savings off the average American cell phone bill of $110 a month by switching to TracFone’s 1,500-minutes-a-month plan

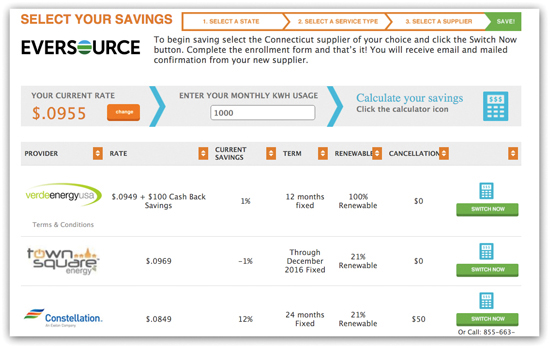

Choose a different energy supplier

Here’s a handy difference between your parents’ era and yours: If you live in one of the enlightened states, you aren’t stuck with one energy company. You can shop and compare utility companies as though they were cell phone carriers.

These states have deregulated electricity, gas, or both: Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas. (To find out what kind of deregulation your state has, click its name at saveonenergy.com/state-information.)

In these states, energy companies compete for your attention and your dollars. With a little research, you can usually find one that charges less than your current supplier. Or maybe you’ll decide to switch suppliers not for price reasons, but because you prefer an energy company that gets its power from renewable sources like sunshine and wind. Either way, you can wind up with something better than what you have now.

What’s amazing about all this is that nothing changes on your end. Nobody comes to the house to fiddle with the wiring. You don’t start getting bills from a new company. Your current electric company still handles the wiring and the billing; the only difference is where it gets the power from.

As you undertake this very special shopping trip, you’ll want answers to three questions:

• Is the lower price just a promotional introductory rate? If so, you risk a higher bill after that teaser period.

• Does this supplier contract renew automatically every year? It’s better if they have to ask your permission each time.

• Am I getting a fixed or floating rate? A fixed price (per kilowatt-hour) never changes during your contract. You win if market prices go up; you lose if they go down.

If you like the sound of all this, the next step is to look over the offers of suppliers in your state. There are websites that compare them, but few are complete, and some are paid to promote certain suppliers.

The better road is to look over the list of suppliers on your state’s website. Use Google to search for ohio energy suppliers list (or whatever your state is)—and click the web result whose address ends in “.gov” or “.us” or “.org.” That’s the official state list.

Savings ballpark: $290 a year

$290 = 27 percent savings from a typical 9.55-cents-per-kilowatt-hour electric utility rate, based on the average U.S. household electricity consumption of 11,000 kWh per year

How to get money for your old gadgets

When you buy an electronic device these days, it’s not like you’re buying a house or a grandfather clock. This isn’t exactly a once-in-a-lifetime purchase.

You know you’ll be ditching it within a couple of years, to make room for a newer, better model.

If you just toss your now-obsolete device in the trash, you’re not only doing a disservice to the environment (there are toxic components in there!)—but you’re also shortchanging yourself. Those old gadgets are worth money.

Your first stop should be one of the online gadget recycling sites, like Gazelle.com. Here even a three-year-old used phone might get you, say, $35. And the process couldn’t be easier. Gazelle sends you a box with the return postage already on it. Put in the phone, send it away, and cash the check. (Gazelle accepts even broken phones.)

You should also check out ecoATM.com to see if there’s an ecoATM near you. There are several thousand in the U.S.

These remarkable machines accept old phones, tablets, and music players, using clever automation to inspect the innards and outards of your device to assess its condition.

If it has any value, the machine spits out cash into your hand and slurps in your device for refurbishing or recycling. (To prevent bad guys from using ecoATMs to make money by selling stolen gadgets, it asks for your driver’s license and thumbprint.)

If your gadget is so old or so broken that nobody would possibly want it, drop it off at a Best Buy or RadioShack store. Those companies offer free recycling. Just drop off your stuff and sleep well, knowing that any valuable parts of your junk will be reclaimed and reused—and that the rest will be safely disposed of.

Earnings ballpark: $40 per gadget

$40 = Gazelle offer for a good-condition Samsung Galaxy S4

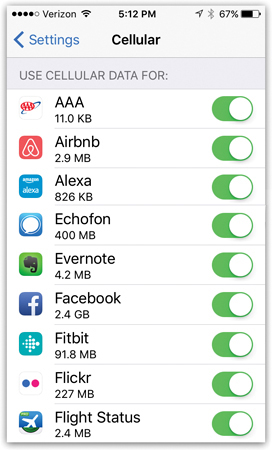

The sneaky way to avoid data-overrun penalties

The cell phone carriers really have it made. They charge you for your smartphone’s use of Internet data, which is measured in gigabytes consumed per month. Well, fine, except how can you possibly predict how much you’ll need this month?

That’s an impossibility. You can’t even see how much you’re using now! Quick: How many gigabytes is a web page? An email? A YouTube video?

It’s not like a car, where there’s a gas gauge staring you in the face. There’s no meter on your phone that shows how much you’re using at this moment, or how much you’ve used this month.

(Oh, you can look up your consumption so far on the carrier’s website—somewhere. And some smartphones keep track in Settings—somewhere. But it’s not prominent in either case, and very few people know about it.)

This setup is no accident. The cell phone carriers hope you’ll go over your monthly allotment. If you do, they slap absurd overage charges onto your bill: $15 per gigabyte, if you use Verizon or AT&T.

That’s not a rare occurrence, either. In a given three-month period, about 20 percent of all Verizon customers, and 28 percent of all AT&T customers, go over their limits and have to pay overage charges.

(If you have T-Mobile, you can ignore this entire tip. With T-Mo, if you exceed your monthly allotment, you don’t incur a penalty. Instead, your Internet just slows down—it will be good for email and web surfing but too slow for video streaming. You can buy more high-speed data if you wish, but you’re never cut off, and you never pay penalties.)

If you’ve ever been slapped with an overage charge, then do what you can never to repeat it again. Paying $15 for a gigabyte of data is like paying $250 for a glass of water.

Here are your options for tracking your data use:

• Install a free “fuel gauge” app. These apps, like DataMan and My Data Manager, watch your data use all day long. They warn you, with pop-up messages, as you reach certain thresholds in your monthly data—at 85 percent, 40 percent, or whatever levels you like. My Data Manager can actually do this for all the phones on a family plan, so that you, the wise adult, always have an eye on how things are going this month.

• Adjust your cap month by month. If, in a certain month, it looks like you or your family is going to exceed your monthly allotment of data, call the carrier and change plans—just for this month! The next more expensive plan usually costs about $15 or $20 more for the month but gets you twice or three times the data. In other words, instead of paying $15 for 1 gigabyte of overage penalty, you’ll pay $15 and get 3 or 6 more gigabytes.

There’s nothing to stop you from “riding” your cell phone plan like this, month after month, upgrading and downgrading as necessary. (Kids going to camp for the summer without their phones? Then knock down your plan to a lower, cheaper data bucket!)

• Identify the gas-guzzlers. Different apps use different amounts of data, and you might be astonished to see which ones are the guilty parties. Your phone shows exactly that breakdown. On an iPhone, open Settings→Cellular, and on an Android phone, open Settings→Data Usage.

In their settings, data-hungry apps like Twitter and Facebook even offer options not to auto-play videos. That’s a great idea, since videos eat up data fast.

Finally, of course, remember that whenever you’re in a Wi-Fi hotspot, you’re not using up any of your monthly data allowance. Go nuts—use all the data you want. Your data limit is for cellular data—when you’re not in Wi-Fi.

Savings ballpark: $60 a year

$60 = What you’d pay if you went over your data allotment four times in a year