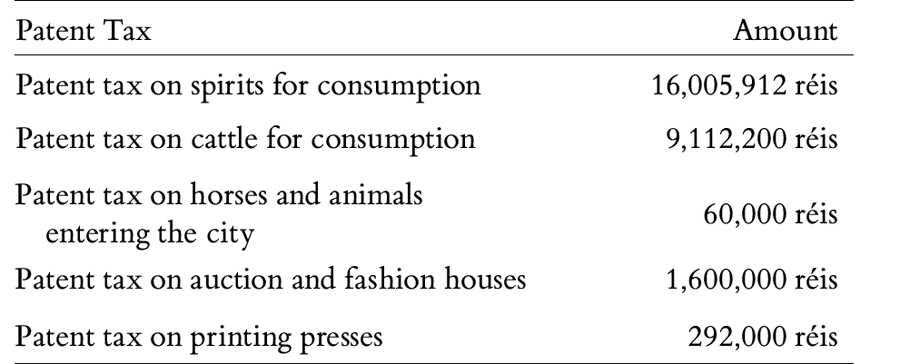

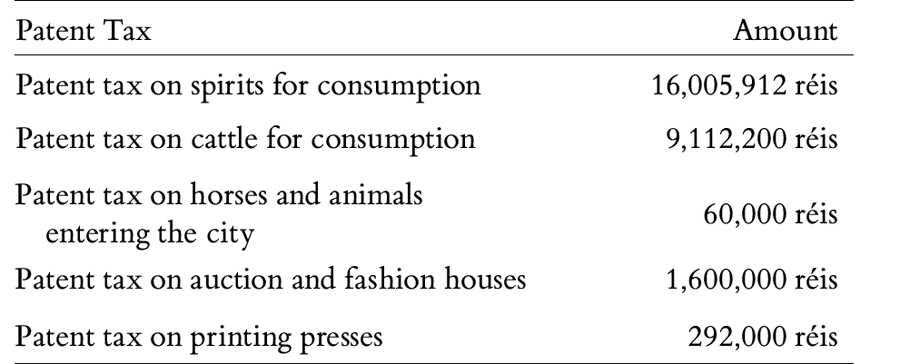

TABLE 7 Patent tax collected by the tax office of the city of Rio de Janeiro in February 1845

Source: “Recebedoria do Município da Corte, fev. de 1845,” Diário do Rio de Janeiro, 4 Mar. 1845, p. 2.

Workers, Slaves, and Free Africans

THE FACT THAT many authors consider Paula Brito to be Machado de Assis’s first “boss” has made a major contribution to the publisher’s inclusion in literary studies in general and specific research into the works of the author generally regarded as Brazil’s greatest writer.1 Nevertheless, the young Machado was not his only employee. Many other workers found jobs at Paula Brito’s bookshop and presses. Thus, going beyond the time period covered by this part of the book, particularly due to a lack of data, in this chapter we will look at the three decades in which the publisher was active in Rio de Janeiro, from November 1831, when he began selling books and sundry items, until his death in December 1861. In fact, Paula Brito’s posthumous inventory would be a good place to start, as it contains references to some of his staff.2

In addition to the cost of renting the building that housed the printing press, gas, medicine, the deceased publisher’s funeral, and mourning for the family, the inventory also included debts incurred from “the wages of clerks, from the wages of newspaper deliverers and collectors, from workers’ salaries.” Noting individually listed cases, we find that Francisco Germano da Silva had been Paula Brito’s clerk, and the publisher’s widow and executrix owed him 550,000 réis for his wages for March 1860. The deliverers, who may have walked the streets of Rio de Janeiro distributing the newspapers and magazines printed by Paula Brito to their subscribers, were Antonio Francisco de Araújo, who was owed 104,580 réis, Manuel José Rodrigues, 34,000 réis, and Moisés Antonio Sabino, 20,000 réis. Compared with the clerk’s salary, the wages of the deliverers were not high, possibly reflecting the unskilled labor involved, and perhaps because they were teenagers and children. Unfortunately, the inventory does not provide more detailed information about these workers. The “List of creditors of the late Francisco de Paula Brito” merely states “Miscellaneous Workers at the Press for the period of two weeks. 257,800 réis.” The inventory also fails to mention any enslaved individuals among the late publisher’s chattels, which does not mean that Paula Brito did not own slaves during his lifetime—on the contrary.

Regarding free workers, Marmota fluminense provides more precise data about the 1850s. During the expansion of the Empresa Dous de Dezembro, which will be discussed in the next part of this book, Paula Brito published an announcement in that newspaper stating that he had hired “monsieur Therier, a skilled portrait artist and lithographer, engaged in Paris.”3 Clemant Bernard Louis Therier had arrived in the imperial capital on February 25, 1853, with a view to working for the Brazilian publisher.4 Therier was not the only Frenchman Paula Brito hired, as there are references to the fact that Dous de Dezembro employed between thirty and forty workers, including Brazilians and Frenchmen.5 However, as early as 1856, the numerous financial problems that pushed that company into bankruptcy were already severe. In fact, Louis Therier left Dous de Dezembro in May 1856, partnering up with another Frenchman, Martinet, to start a new lithographic business in Rio de Janeiro.6 This case is very similar to that of the typographer Luiz de Sousa Teixeira who started his own company after leaving Paula Brito’s press in February 1853.7 There is no evidence that Luiz de Sousa was apprenticed at Paula Brito’s press. However, back in the 1840s, this case may bear some resemblance to that of Teixeira e Sousa, who, as we know, learned the printing trade from Paula Brito and started his own business with the help of his former employer.

Given the lack of records, I had to look for data on the organization of work in the publisher Paula Brito’s world from a variety of sources dating from a range of time periods. However, this search was more promising thanks to the implementation of Decree no. 384 of October 16, 1844, issued by Manuel Alves Branco, then finance minister and secretary of state. Except for the National Press, the purpose of this law was to regulate the collection of an annual tax, called a patent, on printers throughout the Empire. This tax, which was different in each region, varied in towns, coastal cities, cities in the interior, and the capital, as it was calculated on the basis of the number of free and enslaved workers those establishments employed:

Art. 1. All presses in the Empire, with the sole exception of the National Press, shall be subject to an annual Patent Tax, pursuant to Article 10 of the Law of October 21, 1843, according to their size, which shall be regulated as follows:

§ 1 The Presses that employ up to fifteen free workers shall pay:

In towns 20,000 réis

In cities in the interior 40,000 réis

In coastal cities 60,000 réis

In the Imperial Capital 80,000 réis

§ 2 Those which employ from sixteen to thirty free workers will pay double the taxes above, according to their category, and four times as much if they exceed that number [of workers].

§ 3 The employment of enslaved workers, alone or together with free workers, no matter how many [are enslaved], will subject the press to payment of an additional one-tenth of the tax, according to their category.8

Article 2 of the law stated that these workers included typesetters, printers, beaters, and apprentices. The third and fourth articles stated that, at the end of each fiscal year, the owners of the presses had to provide the tax office with a full list of all workers, free and enslaved, employed in their establishments.9

Justiniano José da Rocha launched a direct attack on the “Machiavellian minister” Alves Branco’s Decree no. 384 in the columns of his newspaper. Lest we forget, O Brasil was a Conservative paper in a Liberal administration, which explains da Rocha’s effort to discredit all of the ministry’s tax and tariff policies.10 Attempting demonstrate the unfeasibility of the law, the journalist focused on three very important points for our discussion. Here is the first:

Of all the means of calculating the worth of a press, the minister has chosen the worst: the number of workers is not always a gauge of the work of a press; furthermore, each press is a school where a multitude of boys will learn that trade, perform some light and unskilled tasks there, but be of no use to the business. Counting these boys in order to use them to increase the imposition of the tax means punishing the owner of the press for the very charity with which he helps these youths, giving them a useful future occupation. What printer will take in an apprentice, knowing that he will be taxed for it? Thus, we will soon see the art of printing, which has developed so greatly among us, which provides sustenance for hundreds of families, wither away due to the lack or scarcity of new workers. Thus we will find that this extraordinary number of Brazilian boys, found in abundance in our printing presses, preparing for a means of making a living that does not make them a burden on their parents, instead making them useful, will dwindle bit by bit until they disappear entirely!11

Although the services the youths provided are described as “light and unskilled” and Justiniano da Rocha’s argument was based on the importance of apprenticeships for young boys, his words suggest these workers were an important part of daily life at printing presses. Many of them must have become printers, which may have been the case with Luiz de Sousa Teixeira at Paula Brito’s press. Thanks to the enactment of Decree no. 384, we should know how many apprentices were actually employed in Brazilian presses, if it were not for a second problem that da Rocha mentioned. Printers could easily evade the tax. All they had to do was reduce their workforce during the taxable month by dismissing workers and apprentices. Nevertheless, since “not all [presses] do regular bookkeeping,” there was a third obstacle to the application of the law. Based on his vast experience in the business, da Rocha pointed out that usually printers’ tax bookkeeping was fairly unorthodox, which would greatly hinder the application of a law based on “books that do not exist.”12 From that perspective, Decree no. 384 would first require presses to take a different approach, obliging them to keep more accurate tax records. In any event, the law was implemented, and in February of the following year, printing presses appeared among the other categories of tax collected in Rio de Janeiro.

In 1845, there were sixteen presses in Rio de Janeiro. Dividing this number by the amount collected, a mere 292,000 réis, we find that each establishment paid the City Revenue just 18,250 réis, well below the 80,000 réis required for printers in Rio that employed up to fifteen free workers. According to the figures published in the Diário, Justiniano José da Rocha was quite right in warning that the law would certainly be flouted. It may be that few establishments in Rio voluntarily submitted accurate lists of their workers to the city’s tax collectors.

TABLE 7 Patent tax collected by the tax office of the city of Rio de Janeiro in February 1845

Source: “Recebedoria do Município da Corte, fev. de 1845,” Diário do Rio de Janeiro, 4 Mar. 1845, p. 2.

Other sources indicate that slave labor was widely employed in Rio’s printing presses. In this regard, there are records showing that Paula Brito hired at least one slave to work in his press, a Creole named Francisco who had escaped from his master, João José de Mattos, in August 1858.13 The slave was shrewd, known throughout the city to the point that he had received a benefit performance at the São Januário Theater, and told everyone that he was a freedman by the name of Francisco José de Mattos. The fugitive slave advertisement describes him as “very well dressed and barefoot, and he has a scar under his chin and lacks the tip of a finger right on his right hand.” When he fled, Francisco was selling fish in Praça do Mercado (Market Square), but he had previously worked at the Customs Office and “at Mr. Paula Brito’s business as a beater”—that is, he was responsible for inking the press.14

Antônio, a black slave “aged twenty to twenty-one, of very good appearance” was another fugitive who fled his master wearing “striped trousers and a blue shirt” in November 1831. The ad announcing his escape merely states that Antônio was a “printer” without specifying the type of work he did or where he had been employed.15 If he was a compositor, Antonio must have been able to read and write, like the Creole slave of Colonel Antônio da Costa Barros, a resident of Valongo, who also decided to flee in August 1830. A repeat fugitive, the captive who claimed to be a freedman called himself Mascarenhas, and was described in the advertisement that Colonel Barros published in the Correio mercantil as “short, thin, with small features, well spoken, able to read, write, and count well.”16 However, literate slaves like Mascarenhas could be considered an “island in a sea of illiterates,” to borrow an expression coined by José Murilo de Carvalho.17 Thus, it is not surprising that most slaves employed in presses were printers and beaters. Unlike the roles of compositors and proofreaders, the work of printers was considered hard unskilled manual labor.18 This was the case with Teodoro, who was born a slave of the Jornal do commercio in March 1844. He learned the printing trade but was never taught to read and write. In 1862, Teodoro, who was not only a printer but a practitioner of the Afro-Brazilian martial art/dance, capoeira, was involved in the death of another slave, for which he was tried and convicted. During one of the interrogations to which he was subjected, “he responded that his name was Teodoro, the slave of Júnio Villeneuve & Co., a Creole, born in Rio de Janeiro, who does not know his age, printer, cannot read or write, residing on Rua do Ouvidor, no. 55.”19 Max Fleiuss reported that the first Alauzet press used at the Jornal do commercio was operated by six slaves, two of whom were compositors, a specialized skill for which literacy was a basic requirement.20 In fact, the founders of the Fluminense Printers’ Association, a mutualist, activist society of Rio de Janeiro Printers, included an enslaved compositor.21

In 1846, African slaves were also employed as printers at Heaton & Rensburg, “the largest lithographic establishment in Brazil” according to the American traveler Thomas Ewbank, who also described Mr. Heaton’s astonishment at hearing that in the United States a lithographic printer earned ten to fifteen dollars per week. Ewbank soon learned from the owner of the press that “here, one thousand réis [50 US cents] is a good wage and slaves do not cost us even a quarter of that.”22

It was not unusual for free and enslaved individuals to work side by side in a range of businesses in Imperial Brazil, from printing presses to major establishments like the Baron of Mauá’s shipyard in Ponta da Areia.23 As Mr. Heaton told Mr. Ewbank, the use of slave labor was good business for the printing sector. However, except for the hired-out Creole slave Francisco, studies show that Paula Brito employed very few of his male and female slaves at the press. Thus, although contemporary authors warned that “it was hard to conceive of a system whose impacts are more dire and extensive than those resulting from the existence of domestic slavery,”24 this was precisely the case with our publisher.

Although references to Paula Brito’s “poverty” should be seen in context and were written after the death of a bankrupt man who left numerous debts, it was all too familiar to those who knew and wrote about him.25 However, the fact that the publisher’s human chattel in the mid-1830s consisted of just one enslaved woman does not contradict that image. It is difficult to determine exactly when the publisher purchased the African slave named Maria, from the Congo nation. If she arrived in Rio de Janeiro after the enactment of the law of November 7, 1831, that abolished the African slave trade by making it illegal to enslave captives who disembarked in Brazil, Maria would have been one of the 750,000 Africans unlawfully enslaved in that country between 1831 and 1850 and Paula Brito would have been yet another of many slave owners who benefited from the contraband of Africans to his country.26

What we do know, however, is that in September 1837, Maria Conga was described as “thin and very sallow, [with] full breasts, round, [a] well-shaped face, small eyes, thick eyelids, short hair.”27 Depending on the length of time she was enslaved in Brazil, she may have spoken Portuguese with some difficulty, retaining the vocabulary and accent of her original African language, possibly spoken in the area of the River Zaire in central western Africa.28 We can also deduce the type of work Maria did—domestic service being the most plausible. However, like other urban owners of the limited slave workforce, individuals and families who were generally poor and owned one or two slaves, Paula Brito may have hired out Maria’s services as an additional source of income.29 According to an advertisement for hired-out slaves published in the Diário do Rio de Janeiro in May 1837, Paula Brito did make use of this arrangement. It stated that “the Brito Press” was hiring out “a serious and skilled girl” for 12,000 réis. That was a high price compared with the 320 réis estimated for the same year by Frederico Burlamaqui as the “average (daily) wage of a common slave.”30 But this was not the case with the “serious and skilled girl” who was far from being a “common slave”—she was described as being perfect for “private domestic service,” ideal “for working in a decent house, because her good qualities demand it. She can do anything, and takes care of everything in a loyal, cleanly, and ready manner.”31 The timing suggests that the slave woman may have been Maria Conga. However, we cannot rule out that it may have been another slave woman owned by Paula Brito.

We have seen that Paula Brito married his wife, Rufina, in Itaboraí in May 1833, and the family grew after the birth of their daughters. Their eldest child, Rufina, who was named after her mother, was born on December 28, 1834, and Alexandrina arrived on April 17, 1837.32 Therefore, even if she was hired out to other households, Maria Conga’s labor must also have been essential at Paula Brito’s home between the births of the two girls. After all, Rufina was pregnant with Alexandrina when the couple’s elder daughter was less than three years old. Among other tasks, Maria Conga must have supplied the house with water from the popular Carioca fountain, located near Paula Brito’s house, carrying a jar on her head. Maria may have also have washed the family’s clothes at the same public fountain while chatting with other laundresses and water carriers.33 However, there are no indications that Maria was not hired out during this period, serving other masters and handing over an agreed share of her wages to Paula Brito at the end of each week or work period. We may never know if this happened, nor will we find out why Maria decided to flee at the end of August 1837, four months after her mistress gave birth to her second daughter.

On August 24, Maria “disappeared” from Paula Brito’s home, wearing “a red striped dress, a crimson shawl and a cloth wrapper, fine and new.” The fact that she was well dressed suggests that Maria had enjoyed some privileges in the Paula Brito household. However, this does not exclude the possibility that Rufina and her husband were very harsh, to the point of making the African woman’s enslavement unbearable. In this regard, the Liberal newspaper O grito nacional did not hesitate to accuse the Conservative Paula Brito of “treating his slaves very harshly, having lost the friendship of his groomsman for that reason.”34 Although it was written in the context of the political clashes between Liberals and Conservatives, the newspaper editor’s concerns help provide a plausible explanation for Maria’s escape. It also suggests that Paula Brito owned other slaves, whose names and details are unfortunately unknown to us. Two weeks after the enslaved woman escaped, the publisher printed an advertisement in the Diário asking “anyone who catches her or hears news of her, to deliver her or report her to the house on no. 66, Praça da Constituição, and receive a reward from Mr. Francisco de Paula Brito.”35 However, we do not know what happened to Maria, who decided to decamp from this story in her “cloth wrapper, fine and new.”

Maria Conga’s services must have been sorely missed, particularly by Rufina, who had to do all the housework and take care of the children—Alexandrina was still a baby. Even so, Paula Brito would only try to ease the situation the following year by hiring “a good black woman who can wash and starch clothes [and] cook,” most likely to serve his family.36 Nevertheless, if the problem was finding domestic help, it would soon be resolved. Paula Brito had just been granted the services of two free African women from the Cassange nation called Graça and Querubina who had been rescued from the patache César, a ship impounded for the illegal human trafficking of Africans in May 1838.37

When it was captured, the Cesar was smuggling 202 Africans into Rio de Janeiro. After they were rescued, 191 of them, including Graça and Querubina, were sent to the House of Correction, where they remained until July 11. Then, following their official registration, they were distributed to private dealers by the Third Civil Court Judge and interim Orphans’ Court Judge of Rio de Janeiro.38 In early August, in keeping with the judge’s decision, Registrar José Leite Pereira published a statement in the Diário do Rio de Janeiro urging all those who had been granted free Africans from the César to pick up their letters and receipts of payment for the Africans at his office in Rua do Sabão.39 Paula Brito was one of the dealers who responded to the notice. After enduring the Middle Passage across the Atlantic, Graça and Querubina were embarking on their new lives in the publisher’s household.

About eleven thousand Africans were rescued, freed, and placed under the custody of the Brazilian government between 1821 and 1856. These measures resulted from bilateral agreements between Brazil and Great Britain that formed mixed commissions to judge ships allegedly involved in human trafficking. As of 1817, these agreements established that the men, women, and children found aboard those ships would be freed. However, before being granted full manumission, they were obliged to perform fourteen years’ compulsory service. Thus, Africans rescued from the Atlantic slave trade were either distributed to public institutions in Brazil or offered to private dealers, also known as arrematantes (bidders).40 Graça and Querubina Cassange would only be fully manumitted in August 1854, after sixteen years’ service to the publisher and his family. Cassange was the name of a large slave market located West of the River Kwango in Angola, so their “nation” may not have identified the African women’s birthplace and merely be the place where both women were sold before being put aboard the César.41 Once they were handed over to Paula Brito, we can surmise that Graça and Querubina worked as domestic servants, doing work similar to that possibly performed by the enslaved Maria Conga. Paula Brito may even have made some money by hiring out the African women’s services—a common practice among arrematantes that the jurist Perdigão Malheiro harshly censured.42 We can also surmise that one of them worked as a nanny to help raise Rufina and Alexandrina, the publisher’s daughters. Even so, Graça and Querubina were not the only African women Paula Brito was “given.”

In April 1839, the British warship HMS Grecian captured the brig Leal about fifteen miles off the Brazilian coast, Northwest of Cabo Frio. The Leal was carrying 361 Africans, and the mixed commission based in Rio de Janeiro considered it a “good prize.” Therefore, the Portuguese owner of the Leal, Antonio José de Abreu, its captain, Luiz da Costa Ferreira, and its pilot, Manuel dos Santos Lara, were put on trial. Guimarães denied that he was the owner of the vessel, while the captain and pilot declared that “the Africans seized aboard the Leal were traveling as settlers to an African port.” Despite their feeble excuses, all three were acquitted.43

Paula Brito was granted the services of at least one African man rescued from the Leal, a youth named Fausto of the Sunde nation. Sunde or Mossunde was on the South bank of the River Zaire, also in central western Africa,44 which suggests that Fausto, Graça, and Querubina may have spoken similar languages, which would have been important—particularly from the standpoint of the recent arrival. Records of the other Africans rescued from the Leal, such as the malungos Isaac and Jovita, both from the Muteca nation, enable us to calculate that Fausto was between eleven and thirteen years old when he disembarked in Brazil. However, he died of unknown causes about a year after entering Paula Brito’s house.45

In March 1845, records produced by the clerk for free Africans show that the publisher was using the services of six individuals.46 Fausto had passed away by then; therefore, in addition to Graça and Querubina, there were four more Africans in his employ. Another list, produced in 1861, states that Paula Brito was granted the services of Claro and Agostinho, two African men from the Quelimane nation.47 We have very little information about Claro. Nevertheless, thanks to the records resulting from a misunderstanding involving the manumission of another individual named Agostinho, we do know that the African granted to Paula Brito was sent to the House of Correction in May 1855 and remained there until October of that year. After that, Agostinho was transferred to the Santa Casa de Misericórdia charity hospital, “where he should still be found,” according to a letter to the chief of police of Rio de Janeiro dated August 1862.48

Another free African woman whose services were granted to Paula Brito was called Maria Benguela. There are no records of when, much less from which ship, Maria was rescued. However, in June 1857, Paula Brito decided to transfer her services to Fernando Rodrigues Silva, a notary and clerk in the town of Valença. However, the Orphans’ Court Judge ruled against the move when he found that the publisher owed Maria Benguela two years’ wages.49 The annual salary of a free African placed in the care of the Curator of Free Africans was 12,000 réis. No matter how deep Paula Brito’s financial troubles may have been during the bankruptcy proceedings of the Dous de Dezembro company, precisely between 1856 and 1857, failing to deposit Maria Benguela’s wages sounds like negligence. In fact, willingly or not, the African woman would only be able to go on to Valença after the 24,000 réis had been paid.

Beatriz Mamigonian demonstrates that the working arrangements established between dealers and their Africans were no different from those between masters and slaves. The historian shows that most of the free Africans studied in her vast research were employed in domestic service. In her assessment, this type of unskilled labor drastically reduced those individuals’ prospects of autonomy after manumission. The few free Africans with specialized skills were carpenters and bricklayers, and no Africans rescued from slave ships were found to be working in commerce or mechanical professions.50 In addition to these services, the bookbinding workshop set up at the House of Correction, Rio de Janeiro’s first working prison, may have become a place where some free Africans could receive vocational education as of 1850, when Queirós Law definitively banned the transatlantic slave trade. According to Carlos Eduardo Moreira de Araújo, although they were far from being criminals, many of these workers spent long periods in the House of Correction, mainly employed in building the prison that held them.51 However, some of them must have learned the bookbinding trade and, once freed, they might have found employment in the city’s workshops. Therefore, Agostinho, Claro, and even Fausto may have worked for a time at Paula Brito’s press.

In any event, having been granted the services of seven individuals, one of whom is not identified, Paula Brito found himself in a respectable position in the ranking of private arrematantes in Rio de Janeiro. Although the Decree of November 19, 1835, clearly stipulated that “the same person will not be granted more than eight Africans, unless a larger number of them is needed for the service of a National Establishment,” some private dealers in Rio enjoyed the services of eight to twenty-two individuals.52 Such concessions primarily reflected the social prestige of the men and women who received them, as they were supposedly chosen by virtue of their “recognized probity and character,” according to a Notice from the Department of Justice to the Orphans’ Court Judge dated December 1834.53 However, the selection the individuals who received the services of free Africans was determined by bureaucrats and members of the imperial government, becoming synonymous with political favor, granted in exchange for political support.54

This is made patently clear by an episode that took place in the Chamber of Deputies on May 11, 1839. On that day, the provincial representatives were engaged in a heated debate about the appointment of budget committees. In his speech, Deputy Navarro rejected charges of corruption in the previous cabinet, where the Conservative Bernardo Pereira de Vasconcelos had been Home Secretary and Justice Minister.55 At one point in his impassioned speech, which received a rebuke from the president of the House, Navarro declared:

I cannot speak without agitation; I am not a statue.

And let us not say, gentlemen, that the minister [Bernardo Pereira de Vasconcelos] corrupted this deputy. When an African was wanted, the minister granted him: is there any corruption in that? It is most vile for anyone to be corrupted with two or four Africans; it is most vile for anyone to assume that such corruption is possible. Now what was the ministry doing in this case? It was calculated that for the sake of those Africans, he should not sour a deputy, lose that vote, and send him swiftly over to the opposition, which occurred when [the minister] was not willing to do as they wished.56

Navarro was cobbling a shoe intended to fit Deputy Antônio Carlos Ribeiro de Andrada Machado e Silva, José Bonifácio de Andrada’s brother, who immediately retorted by giving this explanation about the Africans he had received:

MR. ANTÒNIO MACHADO—It is to explain wrong facts, which this young man set forth, that I have asked for the floor. . . .

The young deputy has erred once again, perhaps because he misunderstood the lessons that Mephistopheles of Brazil taught him. A wretched person here [Antônia de Moraes] and my correspondent asked me, as I had some relations with the ministry, to speak in her favor about acquiring the services of some Africans; I requested [them] on behalf of Antônia de Moraes and they gave her two boys; I requested [them] on behalf of Jerônimo Francisco de Freitas Caldas, and they gave him two. I believe that they are not means of corruption . . .

MR. NAVARRO—I have not requested any.

MR. ANDRADA MACHADO—I do not know; nor did I ask for myself, because I do not need any government [for that]; I have provided services to Brazil that the honorable deputy will never render.57

This discussion confirms the importance of free Africans in the political bargaining during the Imperial period. Clientelist networks were formed around the concession of these workers, binding “wretched” people like Antônia de Moraes to deputies and ministers with the shackles of grace and favor.58 In this sense, the cabinet formed on September 19, 1837, headed by Bernardo Pereira de Vasconcelos, seems to have distributed the free Africans’ services lavishly. Published in O Brasil in October 1840, an article by Justiniano José da Rocha, who was also an arrematante, stated that “there was an immense clamor and fuss made by the messrs. who are in power today regarding the September 19 cabinet’s distribution of Africans.”59 Defending the cabinet’s policies in the press, just as Navarro had done in the Chamber of Deputies, da Rocha tried to explain to his readers that “[if] the number of these Africans were known, it would be seen that the enemies of the ministry were just as well apportioned, or more, as its friends.”60

In 1837, all indications are that Paula Brito, then a staunch Liberal-Andradist, was leaning more toward Antônio Carlos Ribeiro de Andrada Machado e Silva. Consequently, according to Justiniano José da Rocha, the publisher would be among the enemies of the September 19 cabinet who were “well apportioned” with the services of free Africans. Nevertheless, Paula Brito would not remain a Liberal and Andradist for long. After the definitive reorganization of the parties and the “Age of Majority Coup,” the publisher joined the ranks of the Conservatives.