Elements of Homological Algebra with Applications

Homological algebra has become an extensive area of algebra since its introduction in the mid-1940’s. Its first aspect, the cohomology and homology groups of a group, was an outgrowth of a problem in topology that arose from an observation by Witold Hurewicz that the homology groups of a path-connected space whose higher homotopy groups are trivial are determined by the fundamental group π1. This presented the problem of providing a mechanism for this dependence. Solutions of this problem were given independently and more or less simultaneously by a number of topologists: Hopf, Eilenberg and MacLane, Freudenthal, and Eckmann [see Cartan and Eilenberg (1956), p. 137, and MacLane (1963), p. 185, listed in References]. All of these solutions involved homology or cohomology groups of π1. The next step was to define the homology and cohomology groups of an arbitrary group and to study them for their own sake. Definitions of the cohomology groups with coefficients in an arbitrary module were given by Eilenberg and MacLane in 1947. At the same time, G. Hochschild introduced cohomology groups for associative algebras. The cohomology theory of Lie algebras, which is a purely algebraic theory corresponding to the cohomology theory of Lie groups, was developed by J. L. Koszul and by Chevalley and Eilenberg. These disparate theories were pulled together by Cartan and Eilenberg (1956) in a cohesive synthesis based on a concept of derived functors from the category of modules over a ring to the category of abelian groups. The derived functors that are needed for the cohomology and homology theories are the functors Ext and Tor, which are the derived functors of the hom and tensor functors respectively.

Whereas the development of homological algebra proper dates from the period of the Second World War. several important precursors of the theory appeared earlier. The earliest was perhaps Hilbert’s syzygy theorem (1890) in invariant theory, which concerned free resolutions of modules for the ring of polynomials in m indeterminates with coefficients in a field. The second cohomology group H2(G. ![]() *) with coefficients in the multiplicative group

*) with coefficients in the multiplicative group ![]() * of non-zero complex numbers appeared in Schur’s work on projective representations of groups (1904). More general second cohomology groups occurred as factor sets in Schreier’s extension theory of groups (1926) and in Emmy Noether’s construction of crossed product algebras (1929). The third cohomology group appeared first in a paper by O. Teichmüller (1940).

* of non-zero complex numbers appeared in Schur’s work on projective representations of groups (1904). More general second cohomology groups occurred as factor sets in Schreier’s extension theory of groups (1926) and in Emmy Noether’s construction of crossed product algebras (1929). The third cohomology group appeared first in a paper by O. Teichmüller (1940).

In this chapter we shall proceed first as quickly as possible to the basic definition and results on derived functors. These will be specialized to the most important instances: Ext and Tor. In the second half of the chapter we shall consider some classical instances of homology theory: cohomology of groups, cohomology of algebras with applications to a radical splitting theorem for finite dimensional algebras due to Wedderburn, homological dimension of modules and rings, and the Hilbert syzygy theorem. Later (sections 8.4 and 8.5), we shall present another application of homology theory to the Brauer group and crossed products.

6.1 ADDITIVE AND ABELIAN CATEGORIES

A substantial part of the theory of modules can be extended to a class of categories called abelian. In particular, homological algebra can be developed for abelian categories. Although we shall stick to modules in our treatment, we will find it convenient to have at hand the definitions and simplest properties of abelian categories. We shall therefore consider these in this section.

We recall that an object 0 of a category C is a zero object if for any object A of C, homc(A, 0) and homc(0, A) are singletons. If 0 and 0′ are zero objects, then there exists a unique isomorphism 0 → 0′ (exercise 3, p. 36). If A, B ∈ obC, we define 0A.B as the morphism 00B0A0 where 0A0 is the unique element of homc(A,0) and 00B is the unique element of homc(0, B). It is easily seen that this morphism is independent of the choice of the zero object. We call 0A,B the zero morphism from A to B. We shall usually drop the subscripts in indicating this element.

We can now give the following

DEFINITION 6.1. A category C is called additive if it satisfies the following conditions:

AC1. C has a zero object.

AC2. For every pair of objects (A,B) in C, a binary composition + is defined on the set homC(A,B) such that (homC(A, B), + ,0A, B) is an abelian group.

AC3. If A,B,C ∈ obC,f,f1,f2 ∈ homC(A,B), and g, g1, g2 ∈ homC(B,C), then

AC4. For any finite set of objects {A1,…, An} there exists an object A and morphisms Pj : A → Aj, ij : Aj → A, 1 ≤ j ≤ n, such that

We remark that AC2 means that we are given, as part of the definition, an abelian group structure on every homC(A , B) whose zero element is the categorically defined 0A, B. AC3 states that the product fg, when defined in the category, is bi-additive. A consequence of this is that for any A, (homC(A, A), + , ·, 0, 1 = 1A) is a ring. We note also that AC4 implies that (A, {pj}) is a product in C of the Aj, 1 ≤ j ≤ n. For, suppose B ∈ obC and we are given ![]() .Then pkf = fk by (1) and if pkf′ = fk for 1 ≤ k ≤ n, then (1) implies that

.Then pkf = fk by (1) and if pkf′ = fk for 1 ≤ k ≤ n, then (1) implies that ![]() Hence f is the only morphism from B to A such that pkf = fk, 1 ≤ k ≤ n, and (A,{pj}) is a product of the Aj. In a similar manner we see that (A, {ij}) is a coproduct of the Aj.

Hence f is the only morphism from B to A such that pkf = fk, 1 ≤ k ≤ n, and (A,{pj}) is a product of the Aj. In a similar manner we see that (A, {ij}) is a coproduct of the Aj.

It is not difficult to show that we can replace AC4 by either

AC4′. C is a category with a product (that is, products exist for arbitrary finite sets of objects of C), or

AC4″. C is a category with a coproduct.

We have seen that AC4 ![]() AC4′ and AC4″ and we shall indicate in the exercises that AC1–3 and AC4′ or AC4″ imply ACR. The advantage of AC4 is that it is self-dual. It follows that the set of conditions defining an additive category is self-dual and hence if C is an additive category, then Cop is an additive category. This is one of the important advantages in dealing with additive categories.

AC4′ and AC4″ and we shall indicate in the exercises that AC1–3 and AC4′ or AC4″ imply ACR. The advantage of AC4 is that it is self-dual. It follows that the set of conditions defining an additive category is self-dual and hence if C is an additive category, then Cop is an additive category. This is one of the important advantages in dealing with additive categories.

If R is a ring, the categories R-mod and mod-R are additive. As in these special cases, in considering functors between additive categories, it is natural to assume that these are additive in the sense that for every pair of objects A,B, the map F of hom(A,B) into hom(FA,FB) is a group homomorphism. In this case, the proof given for modules (p. 98) shows that F preserves finite products (coproducts).

We define next some concepts that are needed to define abelian categories. Let C be a category with a zero (object), f : A →B in C. Then we call k : K → A a kernel of f if (1) k is monic, (2) fk = 0, and (3) for any g : G → A such that fg = 0 there exists a g′ such that g = kg′. Since k is monic, it is clear that g′ is unique. Condition (2) is that

is commutative and (3) is that if the triangle in

is commutative, then this can be completed by g′ : G → K to obtain a commutative diagram. It is clear that if k and k′ are kernels of f, then there exists a unique isomorphism u such that k′ = ku.

In a dual manner we define a cokernel of f as a morphism c : B → C such that (1) c is epic, (2) cf = 0, and (3) for any h :B → H such that hf = 0 there exists h′such that h = h′c.

If f : A → B in R-mod, let K = ker f in the usual sense and let k be the injection of K in A. Then k is monic, fk = 0, and if g is a homomorphism of G into A such that fg = 0, then gG ⊂ K. Hence if we let g′ be the map obtained from g by restricting the codomain to K, then g = kg′. Hence k is a kernel of f. Next let C = B/fA and let c be the canonical homomorphism of B onto C. Then c is epic, cf = 0, and if h : B → H satisfies hf = 0, then fA ⊂ ker h. Hence we have a unique homomorphism h′ : C = B/fA → H such that

is commutative. Thus C is a cokernel of f in the category R-mod.

We can now give the definition of an abelian category

DEFINITION 6.2. A category C is abelian if it is an additive category having the following additional properties:

AC5. Every morphism in C has a kernel and a cokernel.

AC6. Every monic is a kernel of its cokernel and every epic is a cokernel of its kernel.

AC7. Every morphism can be factored as f = me where e is epic and m is monic.

We have seen that if R is a ring, then the categories R-mod and mod-R are additive categories satisfying AC5. We leave it to the reader to show that AC6 and AC7 also hold for R-mod and mod-R. Thus these are abelian categories.

EXERCISES

1. Let C be a category with a zero. Show that for any object A in C, (A, 1A,0) is a product and coproduct of A and 0.

2. Let C be a category, (A, p1, p2) be a product of A1 and A2 in C, (B, q1, q2) a product of B1 and B2 in C, and let hi : Bi → Ai. Show that there exists a unique f : B → A such that hiqi = pif. In particular, if C has a zero and we take (B, q1, q2) = (A1, 1A1, 0) then this gives a unique i1 : A1 → A such that p1i1 = 1A1, p2i1 = 0. Similarly, show that we have a unique i2 : A2 → A such that p1i2 = 0, p2i2 = 1A2. Show that (i1p1 + i2p2)i1 = i1 and (i1p1 + i2p2)i2 = i2. Hence concluded that i1p1 + i2p2 = 1A. Use this to prove that the conditions AC1 – AC3 and AC4′ ![]() AC4. Dualize to prove that AC1 – AC3 and AC4″

AC4. Dualize to prove that AC1 – AC3 and AC4″ ![]() AC4.

AC4.

3. Show that if A and B are objects of an additive category, then 0A, B = 00, B0A, 0, where 0A, 0 is the zero element of hom(A,0), 00, B is the zero element of hom(0, B), and 0A, B is the zero element of the abelian group hom(A, B).

4. Let ![]() be a product of the objects and A1 and A2 in the category C. If fj : B → Aj, denote the unique f : B → A1 Π A2 such that pjf = fj by f1 Π f2. Similarly, if (A1

be a product of the objects and A1 and A2 in the category C. If fj : B → Aj, denote the unique f : B → A1 Π A2 such that pjf = fj by f1 Π f2. Similarly, if (A1 ![]() A2, i1, i2) is a coproduct and gj : Aj → C, write g1

A2, i1, i2) is a coproduct and gj : Aj → C, write g1 ![]() g2 for the unique g : A1

g2 for the unique g : A1 ![]() A2 → C such that gij = gj. Note that if C is additive with the ij and pj as in AC4, then f1 Π f2 = i1f1 + i2f2 and g1

A2 → C such that gij = gj. Note that if C is additive with the ij and pj as in AC4, then f1 Π f2 = i1f1 + i2f2 and g1 ![]() g2 = g1p1 + g2p2. Hence show that if i1, i2, p1, p2 are as in AC4, so A = A1 Π A2 = A1

g2 = g1p1 + g2p2. Hence show that if i1, i2, p1, p2 are as in AC4, so A = A1 Π A2 = A1 ![]() A2, then

A2, then

![]()

(from B →C). Specialize A1 = A2 = 0, g1 = g2 = 1c to obtain the formula

![]()

for the addition in homC(B, C).

5. Use the result of exercise 4 to show that if F is a functor between additive categories that preserves products and coproducts, then F is additive.

6.2 COMPLEXES AND HOMOLOGY

The basic concepts of homological algebra are those of a complex and homomorphisms of complexes that we shall now define.

DEFINITION 6.3. If R is a ring, a complex (C, d) for R is an indexed set C = {Ci} of R-modules indexed by ![]() together with an indexed set d = {di|i ∈

together with an indexed set d = {di|i ∈ ![]() } of R-homomorphisms di : Ci → Ci – 1 such that di – 1di = 0 for all i. If (C, d) and (C′, d′) are R-complexes, a (chain) homomorphism of C into C′ is an indexed set

} of R-homomorphisms di : Ci → Ci – 1 such that di – 1di = 0 for all i. If (C, d) and (C′, d′) are R-complexes, a (chain) homomorphism of C into C′ is an indexed set ![]() of homomorphisms αi :Cj → Ci′ such that we have the commutativity of

of homomorphisms αi :Cj → Ci′ such that we have the commutativity of

for every i. More briefly we write αd = d′.α

These definitions lead to the introduction of a category R-comp of complexes for the ring R. Its objects are the R-complexes (C, d), and for every pair of R-complexes (C, d), (C′, d′), the set hom(C, C′) is the set of chain homomorphisms of (C,d) into (C′, d′). It is clear that these constitute a category, and as we proceed to show, the main features of R-mod carry over to R-comp. We note first that hom(C, C′) has a natural structure of abelian group. This is obtained by defining α + β for α, β ∈ hom(C, C′) by (α + β)i = αi + βi. The commutativity αi – 1di = d′iαi, βi–1di = d′iβi gives (αi – 1 + βi – 1)di = d′i(αi + βi), so α + β ∈ hom(C, C′). Since homR(Ci, C′i) is an abelian group, it follows that hom(C, C′) is an abelian group. It is clear also by referring to the module situation that we have the distributive laws γ(α + β) = γα + γβ, (α + β)δ = αδ + βδ when these products of chain homomorphisms are defined. If (C, d) and (C′, dr) are complexes, we can define their direct sum (C ![]() C′, d

C′, d ![]() d′) by (C + C′)i = Ci

d′) by (C + C′)i = Ci![]() Ci′, di

Ci′, di![]() di′ defined component-wise from

di′ defined component-wise from ![]() . It is clear that

. It is clear that ![]() , so

, so ![]() is indeed a complex. This has an immediate extension to direct sums of more than two complexes. Since everything can be reduced to the module situation, it is quite clear that if we endow the hom sets with the abelian group structure we defined, then the category R-comp becomes an abelian category.

is indeed a complex. This has an immediate extension to direct sums of more than two complexes. Since everything can be reduced to the module situation, it is quite clear that if we endow the hom sets with the abelian group structure we defined, then the category R-comp becomes an abelian category.

The interesting examples of complexes will be encountered in section 4. However, it may be helpful to list some at this point, although most of these will appear to be rather special.

EXAMPLES

1. Any module M becomes a complex in which Cl, = M, i ∈ ![]() , and di = 0 : Ci → Ci – 1.

, and di = 0 : Ci → Ci – 1.

2. A module with differentiation is an R-module equipped with a module endomorphism δ such that δ2 = 0. If (M,δ) is a module with differentiation, we obtain a complex (C, d) in which Cι = 0 for i ≤ 0, Cl = C2 = C2 = C3 = M, Cj = 0 for j > 3, d2 = d3 = δ, and d = 0 if i ≠ 2, 3.

3. Let (M, δ) be a module with a differentiation that is ![]() -graded in the following sense:

-graded in the following sense: ![]() where the Mi are submodules and δ(Mι)

where the Mi are submodules and δ(Mι) ![]() Mi – 1 for every i. Put Ci = Mι and di = δ|Mι. Then C = {Cι}, d = {di} constitute an R-complex.

Mi – 1 for every i. Put Ci = Mι and di = δ|Mι. Then C = {Cι}, d = {di} constitute an R-complex.

4. Any short exact sequence ![]() defines a complex in which

defines a complex in which ![]() if j ≠ 2.3.

if j ≠ 2.3.

We shall now define for each i ∈ ![]() a functor, the ith homology functor, from the category of R-complexes to the category of R-modules. Let (C, d) be a complex and let Zi(C) = ker di so Zi(C) is a submodule of Ci. The elements of zi are called i-cycles. Since didi + l = 0, it is clear that the image di + 1Ci + 1 is a submodule of Zi. We denote this as Bi = Bi(C) and call its elements i-boundaries. The module Hi = Hi(C) = Zi/Bi is called the ith homology module of the complex (C, d). Evidently,

a functor, the ith homology functor, from the category of R-complexes to the category of R-modules. Let (C, d) be a complex and let Zi(C) = ker di so Zi(C) is a submodule of Ci. The elements of zi are called i-cycles. Since didi + l = 0, it is clear that the image di + 1Ci + 1 is a submodule of Zi. We denote this as Bi = Bi(C) and call its elements i-boundaries. The module Hi = Hi(C) = Zi/Bi is called the ith homology module of the complex (C, d). Evidently, ![]() is exact if and only if Hi(C) = 0 and hence the infinite sequence of homomorphisms

is exact if and only if Hi(C) = 0 and hence the infinite sequence of homomorphisms

![]()

is exact if and only if Hi(C) = 0 for all i.

Now let α be a chain homomorphism of (C, d) into the complex (C′,d′). The commutativity condition on (2) implies that ![]() and

and ![]() . Hence the map

. Hence the map ![]() , is a homomorphism of Zi into H′i = Hi(C′) = Z′i/B′i sending Bi into 0. This gives the homomorphism

, is a homomorphism of Zi into H′i = Hi(C′) = Z′i/B′i sending Bi into 0. This gives the homomorphism ![]() of Hi(C) into Hi(C′) such that

of Hi(C) into Hi(C′) such that

![]()

It is trivial to check that the maps (C, d) ![]() Hi(C), hom(C, C′) → hom(Hi(C), Hi(C′)), where the latter is α

Hi(C), hom(C, C′) → hom(Hi(C), Hi(C′)), where the latter is α ![]()

![]() , define a functor from R-comp to R-mod. We call this the ith homology functor from R-comp to R-mod. It is clear that the map α

, define a functor from R-comp to R-mod. We call this the ith homology functor from R-comp to R-mod. It is clear that the map α ![]()

![]() is a homomorphism of abelian groups. Thus the ith homology functor is additive.

is a homomorphism of abelian groups. Thus the ith homology functor is additive.

In the situations we shall encounter in the sequel, the complexes that occur will have either Ci = 0 for i < 0 or Ci = 0 for i > 0. In the first case, the complexes are called positive or chain complexes and in the second, negative or cochain complexes. In the latter case, it is usual to denote C– i by Ci and d – i by di. With this notation, a cochain complex has the appearance

![]()

if we drop the C–i, i > 1. It is usual in this situation to denote ker di by Ziand di – 1Ci – 1 by Bi. The elements of these groups are respectively i-cocycles and i-coboundaries and Hi = Zi/Bi is the ith cohomology group. In the case of if H0, we have H0 = Z0. A chain complex has the form ![]() . In this case H0 = C0/d1C1 = coker d1

. In this case H0 = C0/d1C1 = coker d1

EXERCISES

1. Let α be a homomorphism of the complex (C, d) into the complex (C′, d′). Define ![]() and if

and if ![]() , define

, define ![]() Verify that (C″, d″) is a complex.

Verify that (C″, d″) is a complex.

2. Let (C, d) be a positive complex over a field F such that Σdim Ci < ∞ (equivalently every Ci is finite dimensional and Cn = 0 for n sufficiently large). Let ri = dim Ci, ρi = dim Hi(C). Show that Σ(–1)iρi = Σ(–1)iri.

3. (Amitsur’s complex.) Let S be a commutative algebra over a commutative ring K. Put ![]() , n factors, where

, n factors, where ![]() means

means ![]() K. Note that for any n we have n + 1 algebra isomorphisms

K. Note that for any n we have n + 1 algebra isomorphisms ![]() , of Sn into Sn+1 such that

, of Sn into Sn+1 such that

![]()

For any ring R let U(R) denote the multiplicative group of units of R. Then ![]() . Define

. Define ![]() , by

, by

(e.g., d2u = (δ1u)–1(δ2u)(δ-3u)–1). Note that if i ≥ j, then δi+1δj = δjδi and use this to show that dn + 1dn = 0, the map u ![]() 1. Hence conclude that {U(Sn), dn|n ≥ 0} is a cochain complex.

1. Hence conclude that {U(Sn), dn|n ≥ 0} is a cochain complex.

6.3 LONG EXACT HOMOLOGY SEQUENCE

In this section we shall develop one of the most important tools of homological algebra: the long exact homology sequence arising from a short exact sequence of complexes. By a short exact sequence of complexes we mean a sequence of complexes and chain homomorphisms ![]() such that

such that ![]() is exact for every i ∈

is exact for every i ∈ ![]() , that is, αi is injective, βi is surjective, and ker βi = im αi. We shall indicate this by saying that 0 → C′ → C → C′ → 0 is exact. We have the commutative diagram

, that is, αi is injective, βi is surjective, and ker βi = im αi. We shall indicate this by saying that 0 → C′ → C → C′ → 0 is exact. We have the commutative diagram

in which the rows are exact. The result we wish to prove is

THEOREM 6.1. Let ![]() be an exact sequence of complexes. Then for each i ∈

be an exact sequence of complexes. Then for each i ∈ ![]() we can define a module homomorphism

we can define a module homomorphism ![]() so that the infinite sequence of homology modules

so that the infinite sequence of homology modules

![]()

is exact.

Proof. First, we must define Δi. Let z″i ∈ Zi(C″), so d″iz″i = 0. Since βi is surjective, there exists a ci ∈ Ci such that βici = z″i. Then βi – ldici = d″iβici = d″iz″i = 0. Since ker βi – 1 = im αi – 1 and αi – 1 is injective, there exists a unique z′i – 1 ∈ C′i – 1 such that αi – 1z′i – 1 = dici. Then αi – 2d′i – 1z′i – 1 = di – 1 αi – 1 z′i – 1 = di– 1dici = 0. Since αi – 2 is injective, d′i – 1z′i – 1 = 0 so z′i – 1 ∈ Zi – 1(C′). Our determination of z′i – 1 can be displayed in the formula

![]()

where β– 1i( ) and α– 1i– 1( )denote inverse images. We had to make a choice of ci ∈ βi– 1(z″i) at the first stage. Suppose we make a different one, say, ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() implies that c

implies that c![]() . Then

. Then ![]() . Thus the replacement of ci by

. Thus the replacement of ci by ![]() replaces z′i – 1 by z′i– 1 + d′ic′i. Hence the coset z′i– 1 + Bi– 1(C′) in Hi– 1(C′) is independent of the choice of ci and so we have a map

replaces z′i – 1 by z′i– 1 + d′ic′i. Hence the coset z′i– 1 + Bi– 1(C′) in Hi– 1(C′) is independent of the choice of ci and so we have a map

![]()

of Zi(C″) into Hi – 1(C′). It is clear from (5) that this is a module homomorphism. Now suppose z″i ∈ Bi(C″), say, ![]() . Then we can choose ci+1 ∈ Ci+1 so that βi + 1ci + 1 = c″i+1 and then

. Then we can choose ci+1 ∈ Ci+1 so that βi + 1ci + 1 = c″i+1 and then ![]() . Hence

. Hence ![]() and since

and since ![]() , we have z′i – 1 = 0 in (5). Thus Bi(C″) is in the kernel of the homomorphism (6) and

, we have z′i – 1 = 0 in (5). Thus Bi(C″) is in the kernel of the homomorphism (6) and

![]()

is a homomorphism of Hi(C″)into Hi– 1(C′).

We claim that this definition of Δi makes (4) exact, which means that we have ![]() .

.

I. It is clear that ![]() , so

, so ![]() Suppose zi ∈ Zi(C) and

Suppose zi ∈ Zi(C) and ![]() . There exists a ci + 1 ∈ Ci + 1 such that βi + 1ci + 1 = C″i + 1 and so

. There exists a ci + 1 ∈ Ci + 1 such that βi + 1ci + 1 = C″i + 1 and so ![]() = 0. Then there exists z′i ∈ C′i such that αiz′i = zi-di + 1ci + 1. Then αi– 1d′iz′i. =

= 0. Then there exists z′i ∈ C′i such that αiz′i = zi-di + 1ci + 1. Then αi– 1d′iz′i. = ![]() = 0. Hence d′iz′i = 0 and z′i ∈ Zi(C′). Now

= 0. Hence d′iz′i = 0 and z′i ∈ Zi(C′). Now ![]() . Thus zi + Bi(C) ∈ im

. Thus zi + Bi(C) ∈ im ![]() and hence ker

and hence ker ![]() ⊂ im

⊂ im ![]() and hence ker

and hence ker ![]() = im

= im ![]() .

.

II. Let zi ∈ Zi(C) and let z″ = βizi. Then Δi(z″i+Bi(C″)) = 0 since zi ∈ βi –1(z″i) and dizi = 0, so αi– 10 = diZi. Thus Δi![]() (zi + Bi(C)) = 0 and im

(zi + Bi(C)) = 0 and im ![]() ⊂ ker Δi. Now suppose z″i ∈Zi(C″) satisfies Δi(z″i + Bi(C″)) = 0. This means that if we choose ci ∈ Ci so that βici = z″i and z′i – 1 ∈C′i – 1 so that αi– 1z′i – 1 = dici, then z′i – 1 = d′ic′i for some c′ ∈ C′ii. Then

⊂ ker Δi. Now suppose z″i ∈Zi(C″) satisfies Δi(z″i + Bi(C″)) = 0. This means that if we choose ci ∈ Ci so that βici = z″i and z′i – 1 ∈C′i – 1 so that αi– 1z′i – 1 = dici, then z′i – 1 = d′ic′i for some c′ ∈ C′ii. Then ![]() and di(ci – αic′i) = 0. Also

and di(ci – αic′i) = 0. Also ![]() . Hence, if we put zi = ci – αic′i, then we shall have zi ∈Zi(C) and

. Hence, if we put zi = ci – αic′i, then we shall have zi ∈Zi(C) and ![]() . Thus ker Δi ⊂ im

. Thus ker Δi ⊂ im![]() and hence ker Δi = im

and hence ker Δi = im ![]() .

.

III. If z′i – 1 ∈Zi – 1 and z′i – 1 + Bi – 1(C′) ∈ im Δi, then we have a z″i ∈ Zi(C″) and a ci ∈ Ci such that βici = z″i and αi–1z′i–1 = dici. Then ![]() . Hence im Δi⊂ker

. Hence im Δi⊂ker ![]() –1. Conversely, let z′i–1 +

–1. Conversely, let z′i–1 + ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() . Put z″ = βici. Then d″iz″i =

. Put z″ = βici. Then d″iz″i = ![]() = 0, so z″i ∈ Zi(C″). The definition of Δi shows that

= 0, so z″i ∈ Zi(C″). The definition of Δi shows that ![]() . Thus ker

. Thus ker ![]() –1 ⊂ im Δi and hence ker

–1 ⊂ im Δi and hence ker ![]() – 1 = im Δi.

– 1 = im Δi. ![]()

The homomorphism Δi that we constructed is called the connecting homomorphism of Hi(C″) into Hi – 1(C′) and (4) is the long exact homology sequence determined by the short exact sequence of complexes ![]() . An important feature of the connecting homomorphism is its naturality, which we state as

. An important feature of the connecting homomorphism is its naturality, which we state as

THEOREM 6.2. Suppose we have a diagram of homomorphisms of complexes

which is commutative and has exact rows. Then

is commutative.

By the commutativity of (8) we mean of course the commutativity of

for every i. The proof of the commutativity of (9) is straightforward and is left to the reader.

EXERCISE

1. (The snake lemma.) Let

be a commutative diagram of module homomorphisms with exact columns and middle two rows exact. Let x″ ∈ K″ and let y ∈ M satisfy µy=f″x″. Then ![]() and there exists a unique z′ ∈ N′ such that v′z′ = gy. Define Δx″ = h′z′. Show that Δx″ is independent of the choice of y and that Δ : K″ → C′ is a module homomorphism. Verify that

and there exists a unique z′ ∈ N′ such that v′z′ = gy. Define Δx″ = h′z′. Show that Δx″ is independent of the choice of y and that Δ : K″ → C′ is a module homomorphism. Verify that

![]()

is exact. Show that if µ′ is a monomorphism, then so is K′ and if v is an epimorphism, then so is γ.

6.4 HOMOTOPY

We have seen that a chain homomorphism α of a complex (C,d) into a complex (C′,d′) determines a homomorphism ![]() of the ith homology module Hi(C) into Hi(C′) for every i ∈

of the ith homology module Hi(C) into Hi(C′) for every i ∈ ![]() . There is an important relation between chain homomorphisms of (C,d) to (C′,d′) that automatically guarantees that the corresponding homomorphisms of the homology modules are identical. This is defined in

. There is an important relation between chain homomorphisms of (C,d) to (C′,d′) that automatically guarantees that the corresponding homomorphisms of the homology modules are identical. This is defined in

DEFINITION 6.4. Let α and β be chain homomorphisms of a complex (C, d) into a complex (C′, d′). Then α is said to be homotopic to β if there exists an indexed set s = {si} of module homomorphisms si : Ci → C′i + 1, i ∈ ![]() , such that

, such that

![]()

We indicate homotopy by α ~ β.

If α ~ β, then ![]() =

= ![]() for the corresponding homomorphisms of the homology modules Hi(C) → Hi(C′). For, if zi ∈ Zi(C), then

for the corresponding homomorphisms of the homology modules Hi(C) → Hi(C′). For, if zi ∈ Zi(C), then ![]() and

and ![]() . Hence

. Hence

.

.

It is clear that homotopy is a symmetric and reflexive relation for chain homomorphisms. It is also transitive, since if α ~ β is given by s and β ~ γ is given by t, then

Hence

![]()

Thus s + t = {si + ti} is a homotopy between α and γ.

Homotopies can also be multiplied. Suppose that α ~ β for the chain homomorphisms of (C, d) → (C′, d′) and γ ~ δ for the chain homomorphisms (C′, d′) → (C″, d″). Then γα ~ δβ. We have, say,

Multiplication of the first of these by γi on the left and the second by βi on the right gives

(by (2)). Hence

![]()

Thus γ α ~ δ β via u = {ui} where ui = γi + 1si + tiβi,

6.5 RESOLUTIONS

In the next section we shall achieve the first main objective of this chapter : the definition of the derived functor of an additive functor from the category of modules of a ring to the category of abelian groups. The definition is based on the concept of resolution of a module that we now consider.

DEFINITION 6.5. Let M be an R-module. We define a complex over M as a positive complex C = (C, d) together with a homomorphism ε : C0 → M, called an augmentation, such that εd1 = 0. Thus we have the sequence of homomorphisms

![]()

where the product of any two successive homomorphisms is 0. The complex C, ε over M is called a resolution of M if (10) is exact. This is equivalent to Hi(C) =0 for i > 0 and H0(C) = C0/d1C1 = C0/ker ε ![]() M. A complex C,ε over M is called projective if every Ci is projective.

M. A complex C,ε over M is called projective if every Ci is projective.

We have the following important

THEOREM 6.3. Let C, ε be a projective complex over the module M and let C, ε′ be a resolution of the module M′, μ a homomorphism of M into M′. Then there exists a chain homomorphism α of the complex C into C′ such that µε = ε′α0. Moreover, any two such homomorphisms α and β are homotopic.

Proof. The first assertion amounts to saying that there exist module homomorphisms αi, i > 0, such that

is commutative. Since C0 is projective and ![]() is exact, the homomorphism µε of C0 into M′ can be “lifted” to a homomorphism α0 : C0 → C′0 so that µε = ε′α0. Now suppose we have already determined α0, …, αn–1 so that the commutativity of (11) holds from C0 to Cn – 1. We have

is exact, the homomorphism µε of C0 into M′ can be “lifted” to a homomorphism α0 : C0 → C′0 so that µε = ε′α0. Now suppose we have already determined α0, …, αn–1 so that the commutativity of (11) holds from C0 to Cn – 1. We have ![]() . Hence αn – 1dnCn ⊂ ker d′n – 1 = im d′n = d′nC′n. We can replace C′n– 1 by d′nC′n for which we have the exactness of C′n → d′nC′n → 0. By the projectivity of Cn we have a hommomorphism αn : Cn → C′n such that d′n αn = αn–1dn. This inductive step proves the existence of α. Now let α and β satisfy the conditions. Let γ = α – β. Then we have

. Hence αn – 1dnCn ⊂ ker d′n – 1 = im d′n = d′nC′n. We can replace C′n– 1 by d′nC′n for which we have the exactness of C′n → d′nC′n → 0. By the projectivity of Cn we have a hommomorphism αn : Cn → C′n such that d′n αn = αn–1dn. This inductive step proves the existence of α. Now let α and β satisfy the conditions. Let γ = α – β. Then we have

We have the diagram

Since ε′ γ0 = 0, γ0C0 ⊂ d′1C′1 We have the diagram

with exact row. As before, there exists a homomorphism s0 : C0 → C′1 such that γ0 = d′1s0. Suppose we have determined s0, …, sn–1 such that si : Ci → C′i + 1 and

![]()

Consider γn–sn–1dn. We have ![]() . It follows as before that there exists a homomorphism sn : Cn → Cn + 1 such that d′n + 1sn = γn – sn – 1dn. The sequence of homomorphisms s0, s1, … defines a homotopy of α to β. This completes the proof.

. It follows as before that there exists a homomorphism sn : Cn → Cn + 1 such that d′n + 1sn = γn – sn – 1dn. The sequence of homomorphisms s0, s1, … defines a homotopy of α to β. This completes the proof. ![]()

The existence of a projective resolution of a module is easily established. In fact, as we shall now show, there exists a resolution (10) of M that is free in the sense that the modules Ci are free. First, we represent M as a homomorphic image of a free module C0, which means that we have an exact sequence ker ε ![]() C0

C0 ![]() M → 0 where C0 is free and i is the injection of ker ε. Next we obtain a free module C1 and an epimorphism π of C1 onto ker ε. If we put d1 = iπ : C1 → C0, we have the exact sequence C1

M → 0 where C0 is free and i is the injection of ker ε. Next we obtain a free module C1 and an epimorphism π of C1 onto ker ε. If we put d1 = iπ : C1 → C0, we have the exact sequence C1 ![]() C0

C0 ![]() M → 0. Iteration of this procedure leads to the existence of an exact sequence

M → 0. Iteration of this procedure leads to the existence of an exact sequence

![]()

where the Ci are free. Then (C, d) and ε constitute a free resolution for M.

All of this can be dualized. We define a complex under M to be a pair D, η where D is a cochain complex and η is a homomorphism M → D0 such that d0η = 0. Such a complex under M is called a coresolution of M if

![]()

is exact. We have shown in section 3.11 (p. 159) that any module M can be embedded in an injective module, that is, there exists an exact sequence 0 → M ![]() D0 where D0 is injective. This extends to 0 → M → D0

D0 where D0 is injective. This extends to 0 → M → D0 ![]() coker η where coker η = D0/ηM and π is the canonical homomorphism onto the quotient module. Next we have a monomorphism η1 of coker η into an injective module D1 and hence we have the exact sequence 0 → M

coker η where coker η = D0/ηM and π is the canonical homomorphism onto the quotient module. Next we have a monomorphism η1 of coker η into an injective module D1 and hence we have the exact sequence 0 → M ![]() D0

D0 ![]() D1 where d0 = η1π. Continuing in this way, we obtain a coresolution (12) that is injective in the sense that every Di is injective. The main theorem on resolutions can be dualized as follows.

D1 where d0 = η1π. Continuing in this way, we obtain a coresolution (12) that is injective in the sense that every Di is injective. The main theorem on resolutions can be dualized as follows.

THEOREM 6.4. Let (D, η) be an injective complex under M, (D′, η′) a coresolution of M′, λ a homomorphism of M′ into M. Then there exists a homomorphism g of the complex D′ into the complex D such that ηλ = g0η′. Moreover, any two such homomorphisms are homotopic.

The diagram for the first statement is

The proof of this theorem can be obtained by dualizing the argument used to prove Theorem 6.3. We leave the details to the reader.

We are now ready to define the derived functors of an additive functor F from a category R-mod to the category Ab. Let M be an R-module and let

![]()

be a projective resolution of M. Applying the functor F we obtain a sequence of homomorphisms of abelian groups

![]()

Since F(0) = 0 for a zero homomorphism of a module into a second one and since F is multiplicative, the product of successive homomorphisms in (13) is 0 and so FC = {FCi}, F(d) = {F(di)} with the augmentation Fε is a (positive) complex over FM. If F is exact, that is, preserves exactness, then (13) is exact and the homology groups Hi(FC) = 0 for i ≥ 1. This need not be the case if F is not exact, and these homology groups in a sense measure the departure of F from exactness. At any rate, we now put

![]()

This definition gives

![]()

since we are taking the terms FCi = 0 if i < 0.

Let M′ be a second R-module and suppose we have chosen a projective resolution 0 ← M′ ![]() C0

C0 ![]() C′1 … of M′. from which we obtain the abelian groups Hn(FC′), n ≥ 0. Let μ be a module homomorphism of M into M′. Then we have seen that we can determine a homomorphism a of the complex (C, d) into (C′, d′) such that με = ε′α0. We call α a chain homomorphism over the given homomorphism μ. Since F is an additive functor, we have the homomorphism F(α) of the complex FC into the complex FC′ such that F(μ)F(ε) = F(ε′)F(α0). Thus we have the commutative diagram

C′1 … of M′. from which we obtain the abelian groups Hn(FC′), n ≥ 0. Let μ be a module homomorphism of M into M′. Then we have seen that we can determine a homomorphism a of the complex (C, d) into (C′, d′) such that με = ε′α0. We call α a chain homomorphism over the given homomorphism μ. Since F is an additive functor, we have the homomorphism F(α) of the complex FC into the complex FC′ such that F(μ)F(ε) = F(ε′)F(α0). Thus we have the commutative diagram

Then we have the homomorphism ![]() of Hn(FC) into Hn(FC′). This is independent of the choice of α. For, if β is a second homomorphism of C into C′ over μ, β is homotopic to α, so there exist homomorphisms sn : Cn → C′n + 1, n ≥ 0, such that αn – βn = d′n + 1sn + sn − 1 dn. Since F is additive, application of F to these relations gives

of Hn(FC) into Hn(FC′). This is independent of the choice of α. For, if β is a second homomorphism of C into C′ over μ, β is homotopic to α, so there exist homomorphisms sn : Cn → C′n + 1, n ≥ 0, such that αn – βn = d′n + 1sn + sn − 1 dn. Since F is additive, application of F to these relations gives

![]()

Thus F(α) ~ F(β) and hence ![]() =

= ![]() . We now define LnF(μ) =

. We now define LnF(μ) = ![]() . Thus a homomorphism μ : M → M′ determines a homomorphism LnF(μ) : Hn(FC) → Hn(FC′). We leave it to the reader to carry out the verification that LnF defined by

. Thus a homomorphism μ : M → M′ determines a homomorphism LnF(μ) : Hn(FC) → Hn(FC′). We leave it to the reader to carry out the verification that LnF defined by

is an additive functor from R-mod to Ab. This is called the nth left derived functor of the given functor F.

We now observe that our definitions are essentially independent of the choice of the resolutions. Let ![]() be a second projective resolution of M. Then taking μ = 1 in the foregoing argument, we obtain a unique isomorphism ηn of Hn(FC) onto Hn(F

be a second projective resolution of M. Then taking μ = 1 in the foregoing argument, we obtain a unique isomorphism ηn of Hn(FC) onto Hn(F![]() ). Similarly, another choice

). Similarly, another choice ![]() ′ of projective resolution of M′ yields a unique isomorphism η′n of Hn(FC′) onto Hn(F

′ of projective resolution of M′ yields a unique isomorphism η′n of Hn(FC′) onto Hn(F![]() ′) and LnF is replaced by η′n(LnF)ηn – 1.

′) and LnF is replaced by η′n(LnF)ηn – 1.

From now on we shall assume that for every R-module M we have chosen a particular projective resolution and that this is used to determine the functors LnF. However, we reserve the right to switch from one such resolution to another when it is convenient to do so.

We consider next a short exact sequence 0 → M′ ![]() M

M ![]() M″ → 0 and we shall show that corresponding to such a sequence we have connecting homomorphisms

M″ → 0 and we shall show that corresponding to such a sequence we have connecting homomorphisms

![]()

such that

![]()

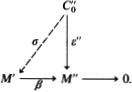

is exact. For this purpose we require the existence of projective resolutions of short exact sequences of homomorphisms of modules. By a projective resolution of such a sequence 0 → M′ → M → M″ → 0 we mean projective resolutions C′, ε′, C, ε, C″, ε″ of M′, M, and M″ respectively together with chain is homomorphisms i: C′ → C, p : C → C″ such that for each n, 0 → C′n → Cn → C″n → 0 is exact and

is commmutative.

We shall now prove the existence of a projective resolution for any short exact sequence of modules 0 → M′ ![]() M

M ![]() M″ → 0. We begin with projective resolutions C′, ε′, and C″, ε″ of M′ and M″ respectively:

M″ → 0. We begin with projective resolutions C′, ε′, and C″, ε″ of M′ and M″ respectively:

We let Cn = C′n ![]() C″n, n = 1, 2, 3, …, inx′n = (x′n, 0) for x′n ∈ C′n, pnxn = x″n for xn = (x′n, x″n). Then 0 → C′n → C′n

C″n, n = 1, 2, 3, …, inx′n = (x′n, 0) for x′n ∈ C′n, pnxn = x″n for xn = (x′n, x″n). Then 0 → C′n → C′n ![]() C″n → C″n → 0 is exact and Cn is projective. We now define εx0 = αε′x′0 + σx″0, dnxn = (d′nx′n + θnx″n, dn″xn″) where σ : C″0 → M′, θn : C′n → C′n–1 are to be determined so that C, ε is a projective resolution of M which together with C′, ε′ and C″, ε″ constitutes a projective resolution for the exact sequence 0 → M′

C″n → C″n → 0 is exact and Cn is projective. We now define εx0 = αε′x′0 + σx″0, dnxn = (d′nx′n + θnx″n, dn″xn″) where σ : C″0 → M′, θn : C′n → C′n–1 are to be determined so that C, ε is a projective resolution of M which together with C′, ε′ and C″, ε″ constitutes a projective resolution for the exact sequence 0 → M′ ![]() M

M ![]() M″ → 0.

M″ → 0.

We have εi0x′0 = ε(x′0, 0) = αε′x′0. Hence commutativity of the left-hand rectangle in (16) is automatic. Also ε″p0x0 = ε″x″0 and βεx0 = β(αε′x′0 + σx″0) = βσx″0. Hence commutativity of the right-hand rectangle in (16) holds if and only if

![]()

We have εd1x1 = ε(d′1x′1 + θx″1, d1″x1″) = αε′θ1x″ + σd″1x1″. Hence εd1 = 0 if and only if

![]()

Similarly, the condition dn– 1dn = 0 is equivalent to

![]()

Now consider the diagram

Since C′0 is projective there exists a σ: C″0 → M′ such that (18) holds. Next we consider

Since ε′C0′ = M′ the row is exact, and since C1″ is projective and βσd′1 = ε″d″1 = 0, there exists a θ1: C1″ → C′0 such that (19) holds (see exercise 4, p. 100). Next we consider

Here again the row is exact, C2″ is projective and ε′θ1d″2 = 0 since αε′θ1d2″ = – σd″1d″2 = 0 and ker α = 0. Hence there exists θ2: C2″ → C′1 such that (19) holds for n = 2. Finally, the same argument establishes (20) for n > 2 using induction and the diagram

It remains to show that … C2 ![]() C1

C1 ![]() C0

C0 ![]() M → 0 is a resolution. For this purpose we regard this sequence of modules and homomorphisms as a complex

M → 0 is a resolution. For this purpose we regard this sequence of modules and homomorphisms as a complex ![]() and similarly we regard the modules and homomorphisms in (17) as complexes

and similarly we regard the modules and homomorphisms in (17) as complexes ![]() and

and ![]() ″. Then we have an exact sequence of complexes 0 →

″. Then we have an exact sequence of complexes 0 → ![]() ′ →

′ → ![]() →

→ ![]() ″ → 0. Since Hi(

″ → 0. Since Hi(![]() ′) = 0 = Hi(

′) = 0 = Hi(![]() ′) it follows from (4) that Hi(

′) it follows from (4) that Hi(![]() ) = 0. Then

) = 0. Then ![]() provides a resolution for M which together with the resolutions for M′ and M″ gives a projective resolution for 0 → M′ → M → M″ → 0.

provides a resolution for M which together with the resolutions for M′ and M″ gives a projective resolution for 0 → M′ → M → M″ → 0.

We can now prove

THEOREM 6.5. Let F be an additive functor from R-mod to Ab. Then for any short exact sequence of R-modules 0 → M′ ![]() M

M ![]() M″ → 0 and any n = 1, 2, 3,… there exists a connecting homomorphism Δn:LnFM″ Ln– 1FM′ such that

M″ → 0 and any n = 1, 2, 3,… there exists a connecting homomorphism Δn:LnFM″ Ln– 1FM′ such that

![]()

is exact

Proof. We construct a projective resolution C′, ε′, C, ε, C″, ε″, i, p for the given short exact sequence of modules. For each n ≥ 0, we have the short exact sequence of projective modules 0 → C′n ![]() Cn

Cn ![]() C″n → 0. Since C″n is projective, this splits and consequently, 0 → FC′n

C″n → 0. Since C″n is projective, this splits and consequently, 0 → FC′n ![]() FC′n

FC′n ![]() FC″n → 0 is split exact. Thus we have a short exact sequence of complexes 0 → F(C′)

FC″n → 0 is split exact. Thus we have a short exact sequence of complexes 0 → F(C′) ![]() F(C)

F(C) ![]() F(C″) → 0. The theorem follows by applying the long exact homology sequence to this short exact sequence of complexes.

F(C″) → 0. The theorem follows by applying the long exact homology sequence to this short exact sequence of complexes. ![]()

Everything we have done can be carried over to coresolutions, and this gives the definition and analogous results for right derived functors. We shall now sketch this, leaving the details to the reader.

Again let F be a functor from R-mod to Ab. For a given R-module M, we choose an injective coresolution 0 → M ![]() D0

D0 ![]() D1

D1 ![]() D2 → …, Applying F, we obtain 0 → FM

D2 → …, Applying F, we obtain 0 → FM ![]() FD0

FD0 ![]() FD1

FD1 ![]() FD2 → … and we obtain the complex FD = {FDi}, F(d) = {F(di)}. Then we put (RnF)M = Hn(FD), n ≥ 0. If M′ is a second R-module, (D′, η′) a coresolution of M′, then for any homomorphism λ:M′ → M we obtain a homomorphism RnF(λ): (RnF)M′ → (RnF)M. This defines the right derived functor of the given functor F. The results we obtained for left derived functors carry over. In particular, we have an analogue of the long exact sequence given in Theorem 6.5. We omit the details.

FD2 → … and we obtain the complex FD = {FDi}, F(d) = {F(di)}. Then we put (RnF)M = Hn(FD), n ≥ 0. If M′ is a second R-module, (D′, η′) a coresolution of M′, then for any homomorphism λ:M′ → M we obtain a homomorphism RnF(λ): (RnF)M′ → (RnF)M. This defines the right derived functor of the given functor F. The results we obtained for left derived functors carry over. In particular, we have an analogue of the long exact sequence given in Theorem 6.5. We omit the details.

EXERCISES

1. Show that if M is projective, then L0FM = FM and LnFM = 0 for n > 0.

2. Show that if F is right exact, then F and L0F are naturally equivalent.

6.7 EXT

In this section and the next we shall consider the most important instances of derived functors. We begin with the contravariant hom functor hom( –, N) defined by a fixed module N, but first we need to indicate the modifications in the foregoing procedure that are required in passing to additive contravariant functors from R-mod to Ab. Such a functor is a (covariant) functor from the opposite category R-modop to Ab, and since arrows are reversed in passing to the opposite category, the roles of injective and projective modules must be interchanged. Accordingly, to define the right derived functor of a contravariant functor G from R-mod to Ab, we begin with a projective resolution 0 ← M ![]() C0

C0 ![]() C1 ← … of the given module M. This gives rise to the sequence 0 → GM

C1 ← … of the given module M. This gives rise to the sequence 0 → GM ![]() GC0

GC0 ![]() GC1 →… and the cochain complex (GC,G(d)) where GC = {GCi} and G(d) = (G(di)}. We define (RnG)M = Hn(GC). In particular, we have (R0G)M = ker (GC0 → GC1). For any μ ∈ homR(M′, M) we obtain a homomorphism (RnG) (μ): (RnG)M → (RnG)M′ and so we obtain the nth rigrto derived functor RnG of G, which is additive and contravariant. Corresponding to a short exact sequence 0 → M′ → M → M″ → 0 we have the long exact cohomology sequence

GC1 →… and the cochain complex (GC,G(d)) where GC = {GCi} and G(d) = (G(di)}. We define (RnG)M = Hn(GC). In particular, we have (R0G)M = ker (GC0 → GC1). For any μ ∈ homR(M′, M) we obtain a homomorphism (RnG) (μ): (RnG)M → (RnG)M′ and so we obtain the nth rigrto derived functor RnG of G, which is additive and contravariant. Corresponding to a short exact sequence 0 → M′ → M → M″ → 0 we have the long exact cohomology sequence

![]()

where RnGM′ → Rn + 1GM″ is given by a connecting homomorphism. The proof is almost identical with that of Theorem 6.5 and is therefore omitted.

We now let G = hom(–, N) the contravariant hom functor determined by a fixed R-module N. We recall the definition: If M ∈ ob R-mod, then hom(–, N)M = homR(M, N) and if α ∈ homR(M, M′), hom(–, N)(α) is the map α* of homR(Mf, N) into homR(M, N) sending any β in the former into βα ∈ homR(M, N). hom(– ,N)M is an abelian group and α* is a group homomorphism. Hence hom(– ,N) is additive. Since (α1α2)* = α*2α1*, the functor hom(– ,N) is contravariant. We recall also that this functor is left exact, that is, if M′ ![]() M

M ![]() M″ → 0 is exact, then 0 → hom(M″, N)

M″ → 0 is exact, then 0 → hom(M″, N) ![]() hom(M, N)

hom(M, N) ![]() hom(M′, N) is exact (p. 105).

hom(M′, N) is exact (p. 105).

The nth right derived functor of hom(–, N) is denoted as Extn(– ,N); its value for the module M is Extn(M, N) (or ExtRn(M, N) if it is desirable to indicate R). If C, ε is a projective resolution for M, then the exactness of C1 → C0 ![]() M → 0 implies that of 0 → hom(M, N)

M → 0 implies that of 0 → hom(M, N) ![]() hom(C0, N) → hom(C1, N). Since Ext0(M, N) is the kernel of the homomorphism of hom(C0, N) into hom(C1, N) it is clear that

hom(C0, N) → hom(C1, N). Since Ext0(M, N) is the kernel of the homomorphism of hom(C0, N) into hom(C1, N) it is clear that

![]()

under the map ε*

Now let 0 → M′ → M → M″ → 0 be a short exact sequence. Then we obtain the long exact sequence

If we use the isomorphism (23), we obtain an imbedding of the exact sequence 0 → hom(M″, N) → hom(M, N) → hom(M′, N) in a long exact sequence

THEOREM 6.6. The following conditions on a module M are equivalent:

(1) M is projective.

(2) Extn(M, N) = 0 for all n ≥ 1 and all modules N.

(3) Ext1 (M, N) = 0 for all N.

Proof. (1) ![]() (2). If M is projective, then 0 ← M

(2). If M is projective, then 0 ← M ![]() C0 = M ← 0 ← … is a projective resolution. The corresponding complex to calculate Extn(M, N) is 0 → hom(M, N) → hom(M, N) → 0 → …. Hence Extn(M, N) = 0 for all n ≥ 1. (2)

C0 = M ← 0 ← … is a projective resolution. The corresponding complex to calculate Extn(M, N) is 0 → hom(M, N) → hom(M, N) → 0 → …. Hence Extn(M, N) = 0 for all n ≥ 1. (2) ![]() (3) is clear. (3)

(3) is clear. (3) ![]() (1). Let M be any module and let 0 → K

(1). Let M be any module and let 0 → K ![]() P

P ![]() M → 0 be a short exact sequence with P projective. Then (25) and the fact that Ext1 (P, N) = 0 yield the exactness of

M → 0 be a short exact sequence with P projective. Then (25) and the fact that Ext1 (P, N) = 0 yield the exactness of

![]()

Now assume Ext1 (M, N) = 0. Then we have the exactness of 0 → hom(M, N) → hom(P, N) → hom(K, N) → 0, which implies that the map η* of hom(P, N) into hom(K, N) is surjective. Now take N = K. Then the surjectivity of η* on hom(K,K) implies that there exists a ζ ∈ hom(P,K) such that 1K = ζη. This implies that the short exact sequence 0 → K ![]() → P

→ P ![]() M → 0 splits. Then M is a direct summand of a projective module and so M is projective.

M → 0 splits. Then M is a direct summand of a projective module and so M is projective. ![]()

The exact sequence (24) in which 0 → K ![]() P

P ![]() M → 0 is exact, M is arbitrary and P is projective gives the following formula for Ext1 (M, N):

M → 0 is exact, M is arbitrary and P is projective gives the following formula for Ext1 (M, N):

![]()

We shall use this formula to relate Ext1 (M, N) with extensions of the module M by the module N. It is this connection that accounts for the name Ext for the functor.

If M and N are modules, we define an extension of M by N to be a short exact sequence

![]()

For brevity we refer to this as “the extension Two extensions E1 and E2 are said to be equivalent if there exists an isomorphism γ: E1 → E2 such that

is commutative. It is easily seen that if γ is a homomorphism from the extension E1 to E2 making (29) commutative, then γ is necessarily an isomorphism. Equivalence of extensions is indeed an equivalence relation. It is clear also that extensions of M by N exist; for, we can construct the split extension

![]()

with the usual i and p.

We shall now define a bijective map of the class E(M, N) of equivalence classes of extensions of M by N with the set Ext1(M, N) More precisely, we shall define a bijective map of E(M, N) onto coker η* where 0 → K ![]() P

P ![]() M → 0 is a projective presentation of M and η* is the corresponding map hom(P, N) → hom(K, N) (η*(λ) = λη). In view of the isomorphism given in (27), this will give the bijection of E(M, N) with Ext1 (M, N).

M → 0 is a projective presentation of M and η* is the corresponding map hom(P, N) → hom(K, N) (η*(λ) = λη). In view of the isomorphism given in (27), this will give the bijection of E(M, N) with Ext1 (M, N).

Let 0 → N ![]() E

E ![]() M → 0 be an extension of M by N. Then we have the diagram

M → 0 be an extension of M by N. Then we have the diagram

without the dotted lines. Since P is projective, there is a homomorphism λ: P → E making the triangle commutative. With this choice of λ there is a unique homomorphism μ :K → N making the rectangle commutative. For, if x ∈ K, then βληx = εηx = 0. Hence ληx ∈ ker β and so there exists a unique y ∈ N such that αy = ληx. We define μ by x ![]() y. Then it is clear that μ is a homomorphism of K into N making the rectangle commutative and μ is unique. Next, let λ′ be a second homomorphism of P into E such that βλ′ = ε. Then β(λ′ – λ) = 0, which implies that there exists a homomorphism τ:P → N such that λ′ – λ = ατ. Then λ′η = (λ + ατ)η = α(λ + τη). Hence μ′ = μ + τη makes

y. Then it is clear that μ is a homomorphism of K into N making the rectangle commutative and μ is unique. Next, let λ′ be a second homomorphism of P into E such that βλ′ = ε. Then β(λ′ – λ) = 0, which implies that there exists a homomorphism τ:P → N such that λ′ – λ = ατ. Then λ′η = (λ + ατ)η = α(λ + τη). Hence μ′ = μ + τη makes

commutative. Since τ ∈ hom (P,N), τη ∈ imη*. Thus μ and μ′ determine the same element of coker η* and we have the map sending the extension E into the element η + imη* of coker η*. It is readily seen, by drawing a diagram, that the replacement of E by an equivalent extension E′ yields the same element μ+im η*. Hence we have a map of E(M, N) into coker η*.

Conversely, let μ ∈ hom(K, N). We form the pushout of η and η (exercise 8, p. 37). Explicitly, we form N ![]() P and let I be the submodule of elements (– μ(x), η(x)), x ∈ K. Put E = (N

P and let I be the submodule of elements (– μ(x), η(x)), x ∈ K. Put E = (N ![]() P)/I and let α be the homomorphism of N into E such that α(y) = (y, 0) + I. Also we have the homomorphism of N

P)/I and let α be the homomorphism of N into E such that α(y) = (y, 0) + I. Also we have the homomorphism of N ![]() P into M such that (y, z)

P into M such that (y, z) ![]() ∈(z),y ∈ N, z ∈ P. This maps I into 0 and so defines a homomorphism β of E = (N

∈(z),y ∈ N, z ∈ P. This maps I into 0 and so defines a homomorphism β of E = (N ![]() P)/I into M such that (y, z) + I

P)/I into M such that (y, z) + I ![]() ε(z). We claim that 0 → N

ε(z). We claim that 0 → N ![]() E

E ![]() M → 0 is exact. First, if α(y) = (y, 0) + I = 0, then (y, 0) = (– μ(x), η(x)), x ∈ K, so η(x) = 0 and x = 0 and y = 0. Thus α is injective. Next, βαy = β((y, 0) + I) = ε(0) = 0, so (βα = 0. Moreover, if β((y, z) + I) = 0, then ∈(z) = 0 so z = η(x), x ∈ K. Then (y, z) + I = (y + μ(x), 0) + I = α(y + μ(x). Hence ker β = im α. Finally, β is surjective since if u ∈ M, then u = ε(z), z ∈ P, and β((0, z) + I) = ε(z) = u. If we put λ(z) = (0, z) + I, then we have the commutativity of the diagram (31). Hence the element of coker η* associated with the equivalence class of the extension E is μ + imη*. This shows that our map is surjective. It is also injective. For, let E be any extension such that the class of E is mapped into the coset μ + imη*. Then we may assume that E

M → 0 is exact. First, if α(y) = (y, 0) + I = 0, then (y, 0) = (– μ(x), η(x)), x ∈ K, so η(x) = 0 and x = 0 and y = 0. Thus α is injective. Next, βαy = β((y, 0) + I) = ε(0) = 0, so (βα = 0. Moreover, if β((y, z) + I) = 0, then ∈(z) = 0 so z = η(x), x ∈ K. Then (y, z) + I = (y + μ(x), 0) + I = α(y + μ(x). Hence ker β = im α. Finally, β is surjective since if u ∈ M, then u = ε(z), z ∈ P, and β((0, z) + I) = ε(z) = u. If we put λ(z) = (0, z) + I, then we have the commutativity of the diagram (31). Hence the element of coker η* associated with the equivalence class of the extension E is μ + imη*. This shows that our map is surjective. It is also injective. For, let E be any extension such that the class of E is mapped into the coset μ + imη*. Then we may assume that E ![]() μ under the original map we defined, and if we form the pushout E′ of μ and η, then E′ is an extension such that E′

μ under the original map we defined, and if we form the pushout E′ of μ and η, then E′ is an extension such that E′ ![]() μ. Now since E′ is a pushout, we have a commutative diagram (29) with E1 = E′ and E2 = E. Then E and E′ are isomorphic. Evidently, this implies injectivity.

μ. Now since E′ is a pushout, we have a commutative diagram (29) with E1 = E′ and E2 = E. Then E and E′ are isomorphic. Evidently, this implies injectivity.

We state this result as

THEOREM 6.7. We have a bijective map of Ext1 (M, N) with the set E(M, N) of equivalence classes of extensions of M by N.

We shall study next the dependence of Extn(M, N) on the argument N. This will lead to the definition of a functor Extn(M, –) and a bifunctor Extn. Let M, N, N′ be R-modules and β a homomorphism of N into N′. As before, let C = {Ci}, ε be a projective resolution of M. Then we have the diagram

where the horizontal maps are as before and the vertical ones are the left multiplications βL by β. It is clear that (32) is commutative and hence we have homomorphisms of the complex hom(C, N) into the complex hom(C, N′); consequently, for each n ≥ 0 we have a homomorphism ![]() of the corresponding cohomology groups. Thus we have the homomorphism

of the corresponding cohomology groups. Thus we have the homomorphism ![]() : Extn(M, N) → Extn(M, N′). It is clear that this defines a functor Extn(M, –) from R-mod to Ab that is additive and covariant.

: Extn(M, N) → Extn(M, N′). It is clear that this defines a functor Extn(M, –) from R-mod to Ab that is additive and covariant.

If α ∈ hom(M′, M), we have the commutative diagram

which gives the commutative diagram

This implies as in the case of the hom functor that we can define a bifunctor Extn from R-mod to Ab (p. 38).

Now suppose that we have a short exact sequence 0 → N′ → N → N″ → 0. As in (32), we have the sequence of homomorphisms of these complexes: hom(C, N′) → hom(C, N) - hom(C, N″). Since Ci, is projective and 0 → N′ → N → N″ → 0 is exact, 0 → hom(Ci, N′) → hom(Ci, N) → hom(Ci, N″) → 0 is exact for every i. Thus 0 → hom(C, N′) → hom(C, N) → hom(C, N″) → 0 is exact. Hence we can apply Theorem 6.1 and the isomorphism of hom(M, N) with Ext0(M, N) to obtain a second long exact sequence of Ext functors:

We shall call the two sequences (24) and (33) the long exact sequences in the first and second variables respectively for Ext.

We can now prove the following analogue of the characterization of projective modules given in Theorem 6.6.

THEOREM 6.8. The following conditions on a module N are equivalent:

(1) N is injective.

(2) Extn(M, N) = 0 for all n ≥ 1 and all modules M.

(3) Ext1 (M, N) = 0 for all M.

Proof. (1) ![]() (2). If N is injective, the exactness of 0 ← M ← C0 ← C1 ← … implies that of 0 → hom(M, N) → hom(C0, N) → hom(C1, N) → …. This implies that Extn(M, N) = 0 for all n ≥ 1. The implications (2)

(2). If N is injective, the exactness of 0 ← M ← C0 ← C1 ← … implies that of 0 → hom(M, N) → hom(C0, N) → hom(C1, N) → …. This implies that Extn(M, N) = 0 for all n ≥ 1. The implications (2) ![]() (3) are trivial, and (3)

(3) are trivial, and (3) ![]() (1) can be obtained as in the proof of Theorem 6.6 by using a short exact sequence 0 → N → Q → L → 0 where Q is injective. We leave it to the reader to complete this argument.

(1) can be obtained as in the proof of Theorem 6.6 by using a short exact sequence 0 → N → Q → L → 0 where Q is injective. We leave it to the reader to complete this argument. ![]()

The functors Extn(M, –) that we have defined by starting with the functors Extn(– ,N) can also be defined directly as the right derived functors of hom(M, –). For the moment, we denote the value of this functor for the module M as ![]() n(M, N). To obtain a determination of this group, we choose an injective coresolution 0 → N

n(M, N). To obtain a determination of this group, we choose an injective coresolution 0 → N ![]() D0

D0 ![]() D1 → … and we obtain the cochain complex hom(M, D):0 → hom(M, D0) → hom(M, D1) → …. Then

D1 → … and we obtain the cochain complex hom(M, D):0 → hom(M, D0) → hom(M, D1) → …. Then ![]() n(M, N) is the nth cohomology group of hom(M, D). The results we had for Ext can easily be established for

n(M, N) is the nth cohomology group of hom(M, D). The results we had for Ext can easily be established for ![]() . In particular, we can show that

. In particular, we can show that ![]() 0(M, N) ≅ hom(M, N) and we have the two long exact sequences for

0(M, N) ≅ hom(M, N) and we have the two long exact sequences for ![]() analogous to (24) and (33). We omit the derivations of these results. Now it can be shown that the bifunctors Extn and

analogous to (24) and (33). We omit the derivations of these results. Now it can be shown that the bifunctors Extn and ![]() n are naturally equivalent. We shall not prove this, but shall be content to prove the following weaker result:

n are naturally equivalent. We shall not prove this, but shall be content to prove the following weaker result:

THEOREM 6.9. Extn(M, N) ≅ ![]() n (M, N)for all n, M, and N.

n (M, N)for all n, M, and N.

Proof. If n = 0, we have Ext0(M, N) ≅ hom(M, N) = ![]() 0(M, N). Now let 0 → K → P → M → 0 be a short exact sequence with P projective. Using the long exact sequence on the first variable for

0(M, N). Now let 0 → K → P → M → 0 be a short exact sequence with P projective. Using the long exact sequence on the first variable for ![]() and

and ![]() 1 (P, N) = 0 we obtain the exact sequence 0 → hom(M, N) → hom(P, N) → hom(K, N) →

1 (P, N) = 0 we obtain the exact sequence 0 → hom(M, N) → hom(P, N) → hom(K, N) → ![]() 1(M, N) → 0. This implies that

1(M, N) → 0. This implies that ![]() 1 (M, N) ≅ hom(K, N)/im hom(P, N). In (27) we showed that Ext1(M, N) ≅ hom(K, N)/im hom(P, N). Hence Ext1(M, N) ≅

1 (M, N) ≅ hom(K, N)/im hom(P, N). In (27) we showed that Ext1(M, N) ≅ hom(K, N)/im hom(P, N). Hence Ext1(M, N) ≅ ![]() 1(M, N). Now let n > 1 and assume the result for n – 1. We refer again to the long exact sequence on the first variable for Ext and obtain

1(M, N). Now let n > 1 and assume the result for n – 1. We refer again to the long exact sequence on the first variable for Ext and obtain

![]()

from which we infer that Extn(M, N) ≅ Extn– 1(K, N). Hence Extn(M, N) ≅ Extn– 1(K, N) ≅ ![]() n– 1(K, N). The same argument gives

n– 1(K, N). The same argument gives ![]() n(M, N) ≅

n(M, N) ≅ ![]() n– 1 (K, N). Hence Extn(M, N) ≅

n– 1 (K, N). Hence Extn(M, N) ≅ ![]() n(M, N).

n(M, N). ![]()

EXERCISES

1. Let R = D, a commutative principal ideal domain. Let M = D/(a), so we have the projective presentation 0 → D → D → M → 0 where the first map is the multiplication by a and the second is the canonical homomorphism onto the factor module. Use (27) and the isomorphism of homD(D, N) with N mapping η into η1 to show that Ext1(M, N) ≅ N/aN. Show that if N = D/(b), then Ext1 (M, N) ≅ D/(a, b) where (a, b) is a g.c.d. of a and b. Use these results and the fundamental structure theorem on finitely generated modules over a p.i.d. (BAI, p. 187) to obtain a formula for Ext1(M, N) for any two finitely generated modules over D.

2. Give a proof of the equivalence of Extn(M, –) and ![]() n(M, –).

n(M, –).

3. Show that in the correspondence between equivalence classes of extensions of M by N and the set Ext1 (M,N) given in Theorem 6.7, the equivalence class of the split extension corresponds to the 0 element of Ext1 (M, N).

4. Let N ![]() Ei

Ei ![]() M, i = 1, 2, be two extensions of M by N. Form E1

M, i = 1, 2, be two extensions of M by N. Form E1 ![]() E2 and let F be the submodule of E1

E2 and let F be the submodule of E1 ![]() E2 consisting of the pairs (z1, z2), zi ∈ Ei such that β1z1 = β2z2. Let K be the subset of E1

E2 consisting of the pairs (z1, z2), zi ∈ Ei such that β1z1 = β2z2. Let K be the subset of E1 ![]() E2 of elements of the form (α1y, – α2y), y ∈ N. Note that K is a submodule of F. Put E = F/K and define maps α: N → E, β: E → M by αy = (α1y, 0) + K = (0, –α2y) + K, β((z1, z2) + K) = α1z1 = β2z2. Show that α and β are module homomorphisms and N

E2 of elements of the form (α1y, – α2y), y ∈ N. Note that K is a submodule of F. Put E = F/K and define maps α: N → E, β: E → M by αy = (α1y, 0) + K = (0, –α2y) + K, β((z1, z2) + K) = α1z1 = β2z2. Show that α and β are module homomorphisms and N ![]() E

E ![]() M, so we have an extension of M by N. This is called the Baer sum of the extensions N

M, so we have an extension of M by N. This is called the Baer sum of the extensions N ![]() Ei

Ei ![]() M. Show that the element of Ext1 (M, N) corresponding to the Baer sum is the sum of the elements corresponding to the given extensions. Use this and exercise 3 to conclude that the set of equivalence classes of extensions of M by N form a group under the composition given by Baer sums with the zero element as the class of the split extension.

M. Show that the element of Ext1 (M, N) corresponding to the Baer sum is the sum of the elements corresponding to the given extensions. Use this and exercise 3 to conclude that the set of equivalence classes of extensions of M by N form a group under the composition given by Baer sums with the zero element as the class of the split extension.

6.8 TOR

If M ∈ mod-R, the category of right modules for the ring R, then M![]() R is the functor from R-mod to Ab that maps a left R-module N into the group M

R is the functor from R-mod to Ab that maps a left R-module N into the group M![]() rN and an element η of homR(N, N′) into 1

rN and an element η of homR(N, N′) into 1![]() η. M

η. M![]() R is additive and right exact. The second condition means that if N′ → N → N″ → 0 is exact, then M

R is additive and right exact. The second condition means that if N′ → N → N″ → 0 is exact, then M![]() N′ → M

N′ → M![]() N → M

N → M![]() N″ → 0 is exact. The nth left derived functor of M

N″ → 0 is exact. The nth left derived functor of M![]() (= M

(= M![]() R) is denoted as Torn(M, –) (or TorRn(M, –)). To obtain Torn(M, N) we choose a projective resolution of N: 0 ← N

R) is denoted as Torn(M, –) (or TorRn(M, –)). To obtain Torn(M, N) we choose a projective resolution of N: 0 ← N ![]() C0 ← … and form the chain complex M

C0 ← … and form the chain complex M![]() C = {M

C = {M![]() Ci}. Then Torn(M, N) is the nth homology group Hn(M

Ci}. Then Torn(M, N) is the nth homology group Hn(M![]() C) of M

C) of M![]() C. By definition, Tor0(M, N) = (M

C. By definition, Tor0(M, N) = (M![]() C0)/im(M

C0)/im(M![]() C1). Since M

C1). Since M![]() is right exact, M

is right exact, M![]() C1 → M

C1 → M![]() C0 → M

C0 → M![]() N → 0 is exact and hence M

N → 0 is exact and hence M ![]() N ≅ (M

N ≅ (M ![]() C0)/im(M

C0)/im(M ![]() C1) = Tor0(M, N).

C1) = Tor0(M, N).

The isomorphism Tor0(M, N) ≅ M![]() N and the long exact sequence of homology imply that if 0 → N′ → N → N″ 0 is exact, then

N and the long exact sequence of homology imply that if 0 → N′ → N → N″ 0 is exact, then

![]()

is exact.

We recall that a right module M is flat if and only if the tensor functor M![]() from the category of left modules to the category of abelian groups is exact (p. 154). We can now give a characterization of flatness in terms of the functor Tor. The result is the following analogue of Theorem 6.6 on the functor Ext.

from the category of left modules to the category of abelian groups is exact (p. 154). We can now give a characterization of flatness in terms of the functor Tor. The result is the following analogue of Theorem 6.6 on the functor Ext.

THEOREM 6.10. The following conditions on a right module M are equivalent:

(1) M is flat.

(2) Torn(M, N) = 0 for all n ≥ 1 and all (left) modules N.

(3) Tor 1(M, N) = 0 for all N.

Proof. (1) ![]() (2). If M is flat and 0 ← N ← C0 ← C1 ← … is a projective resolution of N, then 0 ← M

(2). If M is flat and 0 ← N ← C0 ← C1 ← … is a projective resolution of N, then 0 ← M![]() N ← M

N ← M![]() C0 ← M

C0 ← M![]() C1 ← … is exact. Hence Torn(M, N) = 0 for any n ≥ 1. (2)

C1 ← … is exact. Hence Torn(M, N) = 0 for any n ≥ 1. (2) ![]() (3) is clear. (3)

(3) is clear. (3) ![]() (1). Let 0 → N′ → N ′ N″ ′ 0 be exact. Then the hypothesis that Tor1(M, N′) = 0 implies that 0 → M

(1). Let 0 → N′ → N ′ N″ ′ 0 be exact. Then the hypothesis that Tor1(M, N′) = 0 implies that 0 → M![]() N → → M

N → → M![]() N → M

N → M![]() N″ → 0is exact. Hence M is flat.

N″ → 0is exact. Hence M is flat. ![]()

We consider next the dependence of Torn(M, N) on M. The argument is identical with that used in considering Extn. Let α be a homomorphism of the right module M into the right module M′ and as before let 0 ← N ← C0 ← C1 ← … be a projective resolution for the left module N. Then we have the commutative diagram

where the vertical maps are α![]() 1N, α

1N, α![]() 1C0, α

1C0, α![]() 1Ci, etc. Hence we have a homomorphism of the complex {M

1Ci, etc. Hence we have a homomorphism of the complex {M![]() Ci into the complex and a corresponding homomorphism of the homology groups Torn(M, N) into Torn(M′, N).In this way we obtain a functor Torn(–, N)> from mod-R, the category of right modules for the ring R, to the category Ab that is additive and covariant.

Ci into the complex and a corresponding homomorphism of the homology groups Torn(M, N) into Torn(M′, N).In this way we obtain a functor Torn(–, N)> from mod-R, the category of right modules for the ring R, to the category Ab that is additive and covariant.

We now suppose we have a short exact sequence of right modules 0 → M′ → M → M″ → 0 and as before, let C, ε be a projective resolution for the left module N. Since the Ci are projective, 0 → M′ ![]() Ci → M

Ci → M![]() Ci M″

Ci M″![]() Ci → 0 is exact for every i. Consequently, by Theorem 6.1 and the isomorphism of Tor0(M, N) with M

Ci → 0 is exact for every i. Consequently, by Theorem 6.1 and the isomorphism of Tor0(M, N) with M ![]() N we obtain the long exact sequence for Tor in the first variable:

N we obtain the long exact sequence for Tor in the first variable:

Finally, we note that as in the case of Ext, we can define functors ![]() n(M, N) using a projective resolution of the first argument M. Moreover, we can prove that Torn(M, N) ≅

n(M, N) using a projective resolution of the first argument M. Moreover, we can prove that Torn(M, N) ≅ ![]() n(M, N). The argument is similar to that we gave for Ext and

n(M, N). The argument is similar to that we gave for Ext and ![]() Ext and is left to the reader.

Ext and is left to the reader.

1. Determine Tor1![]() (M, N) if M and N are cyclic groups.

(M, N) if M and N are cyclic groups.

2. Show that Tor1![]() (M, N) is a torsion group for any abelian groups M and N.

(M, N) is a torsion group for any abelian groups M and N.

6.9 COHOMOLOGY OF GROUPS

In the remainder of this chapter we shall consider some of the most important special cases of homological algebra together with their applications to classical problems, some of which provided the impetus to the development of the abstract theory.

We begin with the cohomology of groups and we shall first give the original definition of the cohomology groups of a group, which, unlike the definition of the derived functors, is quite concrete. For our purpose we require the concept of a G-module, which is closely related to a basic notion of representation theory of groups. If G is a group, we define a G-module A to be an abelian group (written additively) on which G acts as endomorphisms. This means that we have a map

![]()

of G × A into A such that

for g, g1, g2 ∈ G, x,y ∈ A. As in representation theory, we can transform this to a more familiar concept by introducing the group ring ![]() [G], which is the free

[G], which is the free ![]() -module with G as base and in which multiplication is defined by

-module with G as base and in which multiplication is defined by

![]()

where αg, βh ∈ ![]() . Then if A is a G-module, A becomes a

. Then if A is a G-module, A becomes a ![]() [G]-module if we define

[G]-module if we define

![]()

The verification is immediate and is left to the reader. Conversely, if A is a ![]() [G]-module, then A becomes a G-module if we define gx as (1g)x.

[G]-module, then A becomes a G-module if we define gx as (1g)x.

A special case of a G-module is obtained by taking A to be any abelian group and defining gx = x for all g ∈ G, x ∈ A. This action of G is called the trivial action. Another example of a G-module is the regular G-module A = G[![]() ] in which the action is h(∑αqg) = ∑ αghg

] in which the action is h(∑αqg) = ∑ αghg

Now let A be a G-module. For any n = 0, 1,2, 3,…, let Cn(G, A) denote the set of functions of n variables in G into the module A. Thus if n > 0, then Cn(G, A) is the set of maps of ![]() into A and if n = 0, a map is just an element of A. Cn(G, A) is an abelian group with the usual definitions of addition and 0: If f, f′ ∈ Cn(G, A), then

into A and if n = 0, a map is just an element of A. Cn(G, A) is an abelian group with the usual definitions of addition and 0: If f, f′ ∈ Cn(G, A), then

In the case of C0(G, A) = A, the group structure is that given in A.

We now define a map δ( = δn) of Cn(G, A) into Cn + 1(G, A). If f ∈ Cn(G,A), then we define δf by

For n = 0, f is an element of A and

![]()

For n = 1 we have

![]()

and for n = 2 we have

![]()

It is clear that δ is a homomorphism of Cn(G, A) into Cn + 1(G, A). Let Zn(G, A) denote its kernel and Bn + 1(G, A) its image in Cn + 1(G, A). It can be verified that δ2f = 0 for every f ∈ Cn(G, A). We shall not carry out this calculation since the result can be derived more simply as a by-product of a result that we shall consider presently. From δ(δf) = 0 we can conclude that Zn(G, A) ⊃ Bn(G, A). Hence we can form the factor group Hn(G, A) = Zn(G, A)/Bn(G, A). This is called the ftth cohomology group of G with coefficients in A.

The foregoing definition is concrete but a bit artificial. The special cases of H1(G, A) and H2(G, A) arose in studying certain natural questions in group theory that we shall consider in the next section. The general definition was suggested by these special cases and by the definition of cohomology groups of a simplicial complex. We shall now give another definition of Hn(G, A) that is functorial in character. For this we consider ![]() as trivial G-module and we consider Extn(

as trivial G-module and we consider Extn(![]() , A) for a given G-module A. We obtain a particular determination of this group by choosing a projective resolution

, A) for a given G-module A. We obtain a particular determination of this group by choosing a projective resolution

![]()

of ![]() as trivial

as trivial ![]() [G]-module. Then we obtain the cochain complex

[G]-module. Then we obtain the cochain complex

![]()

whose nth homology group is a determination of Extn(![]() , A).

, A).

We shall now construct the particular projective resolution (45) that will permit us to identify Extn(![]() , A) with the nth cohomology group Hn(G, A) as we have defined it. We put

, A) with the nth cohomology group Hn(G, A) as we have defined it. We put

Since ![]() [G] is a free

[G] is a free ![]() -module with G as base, Cn is a free

-module with G as base, Cn is a free ![]() -module with base g 0

-module with base g 0![]() g1

g1![]() …

… ![]() gn, gi ∈ G. We have an action of G on Cn defined by

gn, gi ∈ G. We have an action of G on Cn defined by

![]()

which makes Cn a ![]() [G]-module. This is

[G]-module. This is ![]() [G]-free with base

[G]-free with base

![]()

We now define a ![]() [G]-homomorphism dn of Cn into Cn − 1 by its action on the base {(g1, …, gn)}:

[G]-homomorphism dn of Cn into Cn − 1 by its action on the base {(g1, …, gn)}:

where it is understood that for n = 1 we have d1(g1) = g1 − 1 ∈ C0 = ![]() [G]. Also we define a

[G]. Also we define a ![]() [G]-homomorphism ε of C0 into

[G]-homomorphism ε of C0 into ![]() by ε(1) = 1. Then ε(g) = ε(g1) = g1 = 1 and ε(∑αgg) = ∑αg. We proceed to show that 0 ←

by ε(1) = 1. Then ε(g) = ε(g1) = g1 = 1 and ε(∑αgg) = ∑αg. We proceed to show that 0 ← ![]()

![]() C0

C0 ![]() C1 ← … is a projective resolution of

C1 ← … is a projective resolution of ![]() . Since the Ci are free

. Since the Ci are free ![]() [G]-modules, projectivity is clear. It remains to prove the exactness of the indicated sequence of

[G]-modules, projectivity is clear. It remains to prove the exactness of the indicated sequence of ![]() [G]-homomorphisms. This will be done by defining a sequence of contracting homomorphisms:

[G]-homomorphisms. This will be done by defining a sequence of contracting homomorphisms:

![]()

By this we mean that the si are group homomorphisms such that

We observe that {1} is a ![]() -base for

-base for ![]() , G is a

, G is a ![]() -base for C0 =

-base for C0 = ![]() [G], and {g0(g1, …, gn) = g0

[G], and {g0(g1, …, gn) = g0 ![]() g1

g1 ![]() …

… ![]() gn|gi ∈ G} is a

gn|gi ∈ G} is a ![]() -base for Cn, n ≥ 1. Hence we have unique group homomorphisms s – 1 :

-base for Cn, n ≥ 1. Hence we have unique group homomorphisms s – 1 : ![]() → C0, sn : Cn– 1 → Cn such that

→ C0, sn : Cn– 1 → Cn such that

If n > 0, we have

Hence dn + 1sng0(g1, …, gn) + sn– 1dng0(g1, …, gn) = g0(g1, …, gn). This shows that the third equation in (51) holds. Similarly, one verifies the other two equations in (51).

We can now show that the ![]() [G]-homomorphisms ε, dn satisfy εd1 = 0, dndn + 1 = 0, n ≥ 1. By (49), C1 is free with base {(g) = 1