yoga sutra 1.12

abhyāsa vairāgyābhyā tan nirodha

tan nirodha

Containing the mind requires the cultivation of both stability and openness

We have already looked at the concept of nirodha in Chapter 2 and discussed how it is part of both the process and the goal of yoga. In YS 1.12 Patañjali provides a concrete statement of how to reach the state of nirodha, offering us an essential methodology in the form of abhyāsa and vairāgya. Abhyāsa suggests practice and discipline. It means “to travel forwards towards a goal” and, in this case, indicates the necessity for stability and continuity of practice in pursuit of the state of yoga. However, abhyāsa needs a partner lest it becomes overzealous and rigid; this partner is vairāgya.

Although often translated as “detachment” (which seems rather aloof and indifferent), vairāgya is a kind of radical “non-stick openness.” Its literal meaning is “moving away from (vi-) desire (rāga).” But only viewing it as “turning away” can trap us in an unhealthy polarity, constantly oscillating between on/off, yes/no, will I/won't I. This all too often ends in disappointment and failure. Instead, vairāgya can be thought of as cultivating an open space in which new possibilities can arise. We move away from the push/pull duality and towards a place where we have the freedom to use the supports of abhyāsa to disengage from that which blocks us. Vairāgya can be seen as “turning towards” rather than “turning away” from something: from defensiveness to openness, from rejecting to embracing. This understanding of vairāgya allows us to be really touched by life, to experience it fully without clutching at it, holding on, or becoming addicted, defensive or reactive. These two fundamental elements, abhyāsa and vairāgya, lie at the heart of the yoga method; we could even say that they are the yoga method and everything else is elaboration. Just as a bird needs two wings to fly, abhyāsa and vairāgya complement each other and both are essential in helping us to move towards a state of yoga.

tatra sthitau yatno'bhyāsa

Abhyāsa is the effort to be stable there (in a state of nirodha)

yoga sutra 1.13

In YS 1.13, Patañjali defines what he means by abhyāsa: “the effort (yatna) to be stable (sthiti) there (in a state of nirodha).” There are two key concepts here: effort and stability. The effort itself needs to be stable, and also to produce stability. Of course, practice requires effort, but Herculean effort performed intermittently is not abhyāsa. Abhyāsa necessitates consistent, committed and steadfast practice; the most important word in this sūtra is sthiti—stability. Furthermore, stability is both the support and the direction: the measure of this effort (abhyāsa) is the stability it brings. Stability therefore is both in the quality of the effort and is also its fruit.

We could say that abhyāsa is “the effort to put our supports in place.” The supports will help us fly. This effort is not to be done half-heartedly; it requires a steady application of will, and a persistence that is neither rigid and dogmatic on the one hand, nor lacking in vigor and purpose on the other. It is relatively easy to reach a state of clarity—but it will be ephemeral and unstable if it is not well grounded. Abhyāsa is about not slipping and this often requires us to swim upstream a little, to challenge ourselves—always from a place of stability. Too often, yoga is associated with a kind of New Age airiness that can create great experiences that do not last. Abhyāsa is about cultivating traits, and not simply states. Although it is sometimes not a popular message, stability and discipline lie at the very heart of the yoga tradition.

yoga sutra 1.14

sa tu dīrgha-kāla-nairantarya-satkāra-ādarā-āsevito d

ha-bhūmi

ha-bhūmi

Abhyāsa takes a long time, needs to be consistent and performed with integrity and enthusiasm before it is firmly established

Here, Patañjali develops his definition of abhyāsa by describing the qualities of this effort. In order to cultivate (āsevito) stability (d

habhūmi

habhūmi ) we must practice for a long time (dīrgha-kāla), without interruption (nairantarya), with care and sensitivity (satkāra), and with enthusiasm and respect (ādara).1 Let us explore each of these in turn.

) we must practice for a long time (dīrgha-kāla), without interruption (nairantarya), with care and sensitivity (satkāra), and with enthusiasm and respect (ādara).1 Let us explore each of these in turn.

Dīrgha-kāla means “a long time,” and nairantarya means “without interruption.” Yoga practice requires “flying hours”—starting yoga twenty years ago, but only practicing occasionally, is not abhyāsa! Yoga is a gradual path that requires many years to mature and grow. We can liken it to wearing out the sole of a shoe—you have to travel many miles and the process is gradual, but, as the old saying goes, a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. However, this does not mean that the practice has to remain the same throughout the journey. In fact, repeating the same practice can be both limiting and harmful to the body, particularly as we age over the years.

Although much is made in āsana teaching about safety, if one listens to the responses of the body, starts simply and then gradually adds intensity and depth in careful steps, then the matter is largely common sense. This long-term approach to yoga practice therefore needs to be cultivated with care and sensitivity, listening to the body and its responses. We need authenticity (satkāra) in our practice and awareness of our own responses. There also need to be some zeal and challenge (ādara)—we must sometimes approach our edge (physical, mental, emotional); otherwise the practice never deepens and matures. At its most dubious, modern yoga practice can tend to swing between two extremes—either a slavish adherence to a fixed form or a rather random approach where is there is little structure or intelligent methodology (and so progress is rather haphazard).

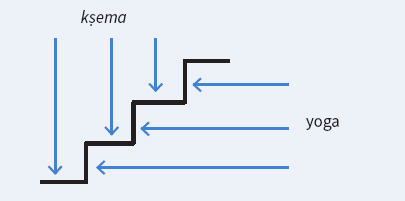

Another meaning of the term yoga is “to reach a point we have not reached before,”2 and in this context, the practice should develop in steps. This is known as yoga-k ema. Yoga here refers to the introduction of new elements into the practice. K

ema. Yoga here refers to the introduction of new elements into the practice. K ema refers to the sthiti elements—that is to say, the maintenance of the practice and integration of these new steps, with sensitivity towards the body's responses. If something can be integrated without any problems for some time, then there is the possibility of taking another step. If not, the practice needs to be revised. Clearly this implies regular practice.

ema refers to the sthiti elements—that is to say, the maintenance of the practice and integration of these new steps, with sensitivity towards the body's responses. If something can be integrated without any problems for some time, then there is the possibility of taking another step. If not, the practice needs to be revised. Clearly this implies regular practice.

This is where the occasional group class can be problematic. If practices are introduced without checking and integrating the preliminary steps, difficulties may arise. For example, sometimes students are taught to retain their breath in prā āyāma before they have developed sufficient ability to simply inhale and exhale. Without creating the foundations by establishing a long and subtle breath, retention of the breath may be experienced as stressful and unsustainable.

āyāma before they have developed sufficient ability to simply inhale and exhale. Without creating the foundations by establishing a long and subtle breath, retention of the breath may be experienced as stressful and unsustainable.

Which is more difficult: yoga or k ema? Do we become attached to the familiarity and security of our regular practice and find it hard to introduce new elements, or do we like new aspects of practice, but find it hard to maintain the form of a practice consistently? For most of us, it is relatively easy to start something new; the challenge is to maintain the practice regularly and consistently.

ema? Do we become attached to the familiarity and security of our regular practice and find it hard to introduce new elements, or do we like new aspects of practice, but find it hard to maintain the form of a practice consistently? For most of us, it is relatively easy to start something new; the challenge is to maintain the practice regularly and consistently.

“For most of us, it is relatively easy to start something new; the challenge is to maintain the practice regularly and consistently.”

This leads us to the issue of regular practice without interruption, of maintaining continuity (nairantarya). Yoga was traditionally a daily practice and the regular practice provided a mirror for our state of being from day to day. Daily practice is certainly ideal, but we have to be realistic and may have to revise our expectations. However, it is important to maintain some sense of continuity: yoga is a training and the body and the mind need time and regularity to respond. Although attending a weekly class can be of considerable benefit, ultimately the practice needs to be much more regular to have optimum impact on the body and mind. It is far better to practice for a shorter time each day than for one two-hour session once a week, just as it is better to clean your teeth for five minutes each day rather than for an hour on a Sunday!

The need for enthusiasm and respect (ādara) points to important attitudes that help to keep the practice potent. Approaching our practice as a chore significantly limits our involvement, so it is important to find a way to look forward to practice. Reflect on the good fortune that we have to live in a place and time where we have the freedom and space to engage with the practice: this is a luxury that many people in the world do not have. Another idea is to dedicate the energy of the practice towards something greater than ourselves, or towards the welfare of others. This embraces the idea of having respect for the practice: it is something special that can touch us deeply if we let it, so we respect it as something precious. When someone first discovers yoga, they may not have the sensitivity or insight to recognize the potential of what they are doing, but as their practice develops it can be like a love affair where the practice offers untold promise, magic and mystery. It is easy to maintain the enthusiasm and respect here—it is as if one becomes enchanted and the practice enlivens all aspects of our lives. But this magic invariably wears off a little at times and we can become stale or uninspired. This is when there is the real challenge of abhyāsa: how to maintain the qualities once the honeymoon period is over.

yoga sutra 1.15

d

a-ānuśravika-vi

a-ānuśravika-vi aya-vit

aya-vit

asya vaśīkāra-sa

asya vaśīkāra-sa jñā vairāgyam

jñā vairāgyam

Vairāgya requires equanimity to both secular and spiritual pursuits

Although abhyāsa is at the heart of the yoga method, on its own it is fundamentally limited. Abhyāsa needs vairāgya, lest it leads to unbending zeal and becomes a prison. We have seen how vairāgya is frequently translated as “detachment” or “lack of desire,” and indeed, the literal meaning is “away from desire.” Although vi aya-vit

aya-vit

asya means “an absence of thirst (vit

asya means “an absence of thirst (vit

asya) towards objects (vi

asya) towards objects (vi aya),” the really important word in the sūtra is vaśīkāra—“mastery.” This term implies an ability to remain centerd, without being knocked off balance and impelled to behave in ways we might later regret. Vairāgya is the ability to reside in a space without the compulsion to act; it gives us the freedom to choose how to respond.

aya),” the really important word in the sūtra is vaśīkāra—“mastery.” This term implies an ability to remain centerd, without being knocked off balance and impelled to behave in ways we might later regret. Vairāgya is the ability to reside in a space without the compulsion to act; it gives us the freedom to choose how to respond.

Interestingly, Patañjali defines vairāgya as applying to both material things and spiritual aspirations. The term d

a-ānuśravika literally means “the seen (d

a-ānuśravika literally means “the seen (d

a) and the heard (ānuśravika).” The first term, d

a) and the heard (ānuśravika).” The first term, d

a, is generally understood to refer to worldly, material objects—things that are tangible and can be seen. The second term, ānuśravika, implies less obvious desires, but includes treasures we may hear about from sacred texts—in other words, spiritual treasures, the promise of heaven. It is common to simply impose desires and aspirations from worldly life onto the spiritual domain; we become enamored not with our car or house but with our abilities in practice or the promise of yogic powers (even if that's just mastering a posture). Nothing really changes; our vanities simply become subtler. Instead, something about our attitude towards our practice, and indeed towards life generally, needs to change. Vairāgya invites us to cultivate less expectation about the results.

a, is generally understood to refer to worldly, material objects—things that are tangible and can be seen. The second term, ānuśravika, implies less obvious desires, but includes treasures we may hear about from sacred texts—in other words, spiritual treasures, the promise of heaven. It is common to simply impose desires and aspirations from worldly life onto the spiritual domain; we become enamored not with our car or house but with our abilities in practice or the promise of yogic powers (even if that's just mastering a posture). Nothing really changes; our vanities simply become subtler. Instead, something about our attitude towards our practice, and indeed towards life generally, needs to change. Vairāgya invites us to cultivate less expectation about the results.

Simply understanding vairāgya as “detachment” could lead us to become cold, unfeeling and somewhat cut off from life. Instead we could consider vairāgya as a state of play that eventually enables a certain mastery (vaśīkāra). When we are confident in our ability to “let be,” to not get caught up in desire or aversion, we have achieved a certain level of vairāgya. This is neither easy nor instant. First we may need to deliberately turn away from and shun certain experiences in order to protect ourselves from habitual desires, aversions or ways of being. However, as we cultivate a new orientation, we can begin to be more open to experiences without feeling overwhelmed or destabilized. We can therefore see the cultivation of vairāgya as a vinyāsa: mastery arises only after careful steps which ensure the protection and stability of our fledgling vairāgya.3 Ultimately, the test of vairāgya is the ability to let ourselves be touched by life and yet still remain open and innocent.

yoga sutra 1.16

tat para puru

puru a-khyāter gu

a-khyāter gu a-vait

a-vait

yam

yam

The highest vairāgya arises when we remain unreactive to all of prak ti, and we intuit the pure awareness of puru

ti, and we intuit the pure awareness of puru a

a

Which is more important: abhyāsa or vairāgya? As is often the case, their order in the Yoga Sūtra is significant: abhyāsa comes before vairāgya. We have to start with some abhyāsa. But the Yoga Sūtra suggests that ultimately it is the cultivation of vairāgya that will take us to the highest stages of yoga. In fact, Patañjali states that the highest vairāgya, where we have no thirst for the gu a themselves (gu

a themselves (gu a-vait

a-vait

yam), will only come from a profound vision of our deepest nature (puru

yam), will only come from a profound vision of our deepest nature (puru a-khyāti). This is not surprising: the more we have confidence in our own profound nature, something that transcends mundane experience, the more we can be open and responsive to the world around us without the need for defensiveness and fear. This seems to be a radical path of freedom: not freedom from the world, but freedom within the world.

a-khyāti). This is not surprising: the more we have confidence in our own profound nature, something that transcends mundane experience, the more we can be open and responsive to the world around us without the need for defensiveness and fear. This seems to be a radical path of freedom: not freedom from the world, but freedom within the world.

Sādhana: Abhyāsa and vairāgya in āsana and prā āyāma

āyāma

Let us take some practical examples to see how we can apply the idea of “putting support in place”—our interpretation of Patañjali's definition of abhyāsa. In any āsana, we could ask: what do we need to do, to ensure that the posture is stable and supported? There needs to be some effort and commitment, skillfully applied, and the ability to know when, and how, to release the body. Yoga postures and their myriad variations can often deliberately put the body into unusual configurations where stability is compromised and challenged.

In this variation of dvi pāda pī ham (fig 5.1), we start in supta baddha konāsana, with the soles of the feet together and the hips open.

ham (fig 5.1), we start in supta baddha konāsana, with the soles of the feet together and the hips open.

When we enter the posture, by raising the hips off the floor, the pelvis can feel quite unstable as it is not obviously “held.” Consequently we need to find and establish stability; this may work the body in unfamiliar ways and require considerable effort. Push the feet together!

There is also the question of what we need to release in order for this support to be cleanly transmitted. Sometimes people suggest that you simply have to “let go” in an āsana—but this is an oversimplification: letting go of unnecessary effort allows you to find your real supports. This requires a commitment to the support that represents true abhyāsa. Simply “letting go” can result in a posture becoming weak, insubstantial or impotent. Only when true support in a posture is found can a radical letting go—vairāgya—arise. Now the posture can really touch us.

This is as much a mental attitude as a physical practice: can I let the posture really work on me while I remain open to its effect? We are inviting new feelings into the body, which can be challenging. Without such a step, āsana can simply reinforce preexisting patterns, and this becomes a more subtle and enduring problem the more that we practice. We simply become more of who we already are! Vairāgya in āsana therefore allows us to be carried by a posture, opened up and profoundly touched by the experience. This is a letting go in order to turn towards the experience and its potential effects. In a sense, we “get out of the way of ourselves.” In this way, even simple postures can restructure us—not in a negative sense, but by disrupting old physical patterns and opening up new possibilities. Instead of “doing postures,” we let them “do us.”

The breath is the fundamental tool to find, clarify and commit to our supports, and then to allow ourselves to be opened up and touched by the posture. Using the breath effectively is both an essential part of our method (abhyāsa) and, through its qualities, reflects the experience we hope to cultivate (vairāgya).4

When we breathe naturally in our everyday lives, the inhalation is the more active part of the breath, whereas the exhalation is a sort of “rebound”; we relax as we breathe out and there is a “letting go.” However, this can lead to a collapse on the exhalation. For example, when we stand in samasthiti with natural breathing, it is easy to experience a slight slumping with each exhalation, so that the space between the head and pelvis gradually reduces. Eventually, if unchecked, the cumulative effect of this exhaling will result in a rounded upper back and a slouched posture.

However, when we work with āsana and the breath in a more conscious and focused way, we can invert this relationship, so that the exhalation now becomes the more active aspect of the breath. Because the effort is applied more on the exhalation, we could say that this is the place of abhyāsa. One way of ensuring that this happens is to keep the head still as we breathe out, as if it is directly supported by the pelvis. This is done by tucking the chin in slightly as we exhale, and keeping the back of the neck lengthened, while lifting the sternum up towards the chin. This technique, called jālandhara bandha (“containing the nectar”5) is extremely effective for keeping the head steady as we exhale, and thereby avoiding a collapse of space between the head and the pelvis.

As well as maintaining the space between head and pelvis, jālandhara bandha also encourages a feeling of drawing the exhalation up from the lower abdomen. We apply effort to hold the head steady (but not so tightly that it creates neck tension) as we exhale. The effort of holding the head still as we exhale actually pulls the abdomen up and in, making it a firm platform from which to launch the subsequent inhalation. By maintaining and utilizing this firmness of the abdomen as we breathe in, the inhalation becomes more relaxed and the body lengthens. We allow ourselves to be touched and opened by the inhalation. There is a feeling of letting be—vairāgya—as the breath opens a space deep within our axis and we grow taller.

To sum up: applying effort to the exhalation creates a stable base. We could say that the exhalation has something of the qualities of abhyāsa. The inhalation then enters and opens a clear space deep within us and we are touched. In this sense, the inhalation has something of vairāgya.6

These principles also apply to prā āyāma. Many elements in the practice of prā

āyāma. Many elements in the practice of prā āyāma have a role in creating support and require us to engage with them carefully and diligently—this is abhyāsa. Examples of such elements include: the form of the posture for prā

āyāma have a role in creating support and require us to engage with them carefully and diligently—this is abhyāsa. Examples of such elements include: the form of the posture for prā āyāma, the technique of prā

āyāma, the technique of prā āyāma, the length of the breath and structure of the practice. And once these are well established, vairāgya is very much related to how we give ourselves to the practice and how we allow it to restructure our experience. The practice opens a new space, allowing us to be more stable and more empowered, freer to make choices without compulsion.

āyāma, the length of the breath and structure of the practice. And once these are well established, vairāgya is very much related to how we give ourselves to the practice and how we allow it to restructure our experience. The practice opens a new space, allowing us to be more stable and more empowered, freer to make choices without compulsion.

In the same way, other aspects of our life can be informed by abhyāsa and vairāgya. Can we bring the qualities of abhyāsa to the disciplines and activities of our life so that we relate to them as useful supports? Our diet? Our lifestyle? Our relationships? And can we work with our attitudes so that we remain open to the experiences that they offer without becoming rigid, defensive or stuck? Abhyāsa gives us the support, direction and energy to keep moving forwards, and vairāgya gives us an openness to the richness of life without becoming stuck in the past or rigid about the future. This is freedom indeed, and a worthy aspiration for the practice of yoga.