yoga sutra 2.32

śauca-sa to

to a-tapa

a-tapa -svādhyāya-īśvara-pra

-svādhyāya-īśvara-pra idhānāni niyamā

idhānāni niyamā

The niyama are self-care, contentment, purifying discipline, self-enquiry and a trust in the process of Life

The niyama are the second of the eight limbs of a

ā

ā ga yoga. They are five attitudes, or restraints, presented by Patañjali to free us from unhelpful habits and thereby guide us to greater independence and peace of mind. Like the yama, they can be structured as an initial pair (setting the basic conditions), a subsequent pair (providing the means to go deeper), and a final niyama that takes us beyond ourselves to far greater horizons.

ga yoga. They are five attitudes, or restraints, presented by Patañjali to free us from unhelpful habits and thereby guide us to greater independence and peace of mind. Like the yama, they can be structured as an initial pair (setting the basic conditions), a subsequent pair (providing the means to go deeper), and a final niyama that takes us beyond ourselves to far greater horizons.

They are given as a list in YS 2.32 and then an additional sūtra is offered for each niyama that describes the results when it is mastered and applied. This structure mirrors the sūtras on yama.

The first of the niyama, śauca, is self-care, often translated as “cleanliness.” Heading the list, it has a special place—the others are the means to refine and condition it. Although “cleanliness” may appear to be relatively superficial, it assumes a new significance when understood as the profound cultivation of lightness and clarity (sattva gu a) in body and mind. It is both a starting point and an important goal: sattva is the support within our minds for the most profound realization. Patañjali distinguishes inner śauca (psychological) from outer śauca (bodily), and two sūtras, YS 2.40 and 2.41, give the fruits of each. Śauca, often quickly glossed over, is fundamental and central to the yoga path.

a) in body and mind. It is both a starting point and an important goal: sattva is the support within our minds for the most profound realization. Patañjali distinguishes inner śauca (psychological) from outer śauca (bodily), and two sūtras, YS 2.40 and 2.41, give the fruits of each. Śauca, often quickly glossed over, is fundamental and central to the yoga path.

The second niyama, sa to

to a, is “contentment” and shifts the emphasis from the material (i.e., our body and mind) towards the spiritual. Here, freedom from desire and transcending the duality of “normal” happiness and unhappiness is the path to a deeper contentment. Sa

a, is “contentment” and shifts the emphasis from the material (i.e., our body and mind) towards the spiritual. Here, freedom from desire and transcending the duality of “normal” happiness and unhappiness is the path to a deeper contentment. Sa to

to a is the means to be profoundly at ease within ourselves.

a is the means to be profoundly at ease within ourselves.

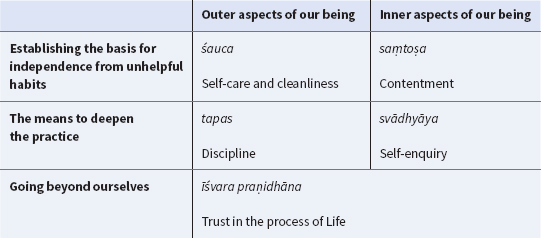

The three remaining niyama are the components of kriyā yoga and we shall discuss these further in Chapter 13. Through tapas (discipline) and svādhyāya (study, listening), we refine our relationship with ourselves to actively deepen our śauca and sa to

to a. Tapas is more concerned with working on the material (including the mind), while svādhyāya takes us more inward towards the spiritual Self. Īśvara pra

a. Tapas is more concerned with working on the material (including the mind), while svādhyāya takes us more inward towards the spiritual Self. Īśvara pra idhāna, the last niyama, has a similar position to aparigraha in the framework of the yama. Īśvara pra

idhāna, the last niyama, has a similar position to aparigraha in the framework of the yama. Īśvara pra idhāna, a trust in the process of Life, requires that we consider our relationship to forces beyond our control and our place within the greater world order. We explore this in Chapter 16.

idhāna, a trust in the process of Life, requires that we consider our relationship to forces beyond our control and our place within the greater world order. We explore this in Chapter 16.

We can explore niyama using a similar framework to the yama: as two pairs plus one. Whereas two yama focus on the other person in a relationship, and two focus on oneself, with the niyama, two concern the outer aspects of our being and two the inner.

Śauca is about how we care for ourselves and our environment, and is thus more outer. Sa to

to a is more inner, concerned with a contentment arising from our very being. Thus, the focus of śauca is the material (prak

a is more inner, concerned with a contentment arising from our very being. Thus, the focus of śauca is the material (prak ti), while sa

ti), while sa to

to a's focus is linked more to the spiritual (puru

a's focus is linked more to the spiritual (puru a). Śauca and sa

a). Śauca and sa to

to a are the basis of a healthy relationship with ourselves: we are content and at ease, we care for ourselves and we live in a way that supports lightness and clarity.

a are the basis of a healthy relationship with ourselves: we are content and at ease, we care for ourselves and we live in a way that supports lightness and clarity.

Śauca and sa to

to a are a profound and important part of the practice and, as with so many of the principles of the Yoga Sūtra, they have multiple levels. While these first two establish the foundations of the niyama, it is also important to consider our motivations in practicing yoga. There are likely to be many factors that draw us to the teachings and the practice. The Ha

a are a profound and important part of the practice and, as with so many of the principles of the Yoga Sūtra, they have multiple levels. While these first two establish the foundations of the niyama, it is also important to consider our motivations in practicing yoga. There are likely to be many factors that draw us to the teachings and the practice. The Ha ha Yoga Pradīpikā warns of graha niyama,1 which Krishnamacharya understood as a self-discipline that is maintained too tightly, or for the wrong reasons. For many yoga practitioners, aspects of the practice can reinforce or indulge unhealthy motivations. Is our preoccupation with āsana largely driven by a desire to cultivate the body or stay slim? Does puru

ha Yoga Pradīpikā warns of graha niyama,1 which Krishnamacharya understood as a self-discipline that is maintained too tightly, or for the wrong reasons. For many yoga practitioners, aspects of the practice can reinforce or indulge unhealthy motivations. Is our preoccupation with āsana largely driven by a desire to cultivate the body or stay slim? Does puru a offer a promise of life beyond death and salve our basic existential fears? Are we adopting a philosophy that allows us to reject a society and culture that we simply cannot cope with? Perhaps this is inevitable to a degree, but we should be clear about why we are drawn to some things and not others. Often what really drives us is not immediately apparent, and it is important to be vigilant. The principle of ahi

a offer a promise of life beyond death and salve our basic existential fears? Are we adopting a philosophy that allows us to reject a society and culture that we simply cannot cope with? Perhaps this is inevitable to a degree, but we should be clear about why we are drawn to some things and not others. Often what really drives us is not immediately apparent, and it is important to be vigilant. The principle of ahi sā applies to ourselves as well as to others, and we must be careful that we do not simply reinforce our own subtle psychological pathologies, or engage in a pursuit that verges on self-abuse. Niyama held “too tightly” could be just that. Niyama—and śauca/sa

sā applies to ourselves as well as to others, and we must be careful that we do not simply reinforce our own subtle psychological pathologies, or engage in a pursuit that verges on self-abuse. Niyama held “too tightly” could be just that. Niyama—and śauca/sa to

to a in particular—should help to establish a healthy relationship with ourselves.

a in particular—should help to establish a healthy relationship with ourselves.

yoga sutra 2.40

śaucāt svā ga-jugupsā parair asa

ga-jugupsā parair asa sarga

sarga

From self-care arise a lack of obsession with our own bodies and a reduction of infatuation with those of others

Peter Hersnack interpreted śauca as “caring for oneself as if for another.”2 It is often translated as “purity,” but this can feel too austere—such as wearing a hair shirt in order to purify our sins. Alternatively, as stated above, it may be translated as “cleanliness”—but this feels too superficial. Śauca as “self-care,” however, has a more nurturing feel to it: it invites us to look after ourselves in a way which is tender and protective. Often it is easier to take care of someone else—a loved one, a relative or even a pet. We may trivialize our own needs in a way that we would not if we were caring for another. Mistaken ideas about yoga, detachment from the world and the rejection of material things can reinforce such tendencies. For some, neglecting cleanliness, appearance and other elements of self-care can indicate (misplaced) spiritual superiority. But “caring for oneself as if for another” asks us to value ourselves and consider how our bodies and minds can be a fit support for an experience of yoga.

However, “caring for ourselves” can also easily become confused with self-indulgence or neurotic concerns about our health.

The Sanskrit root of śauca is “to shine” or “gleam,” which are both associated with sattva gu a. Sattva gu

a. Sattva gu a has the qualities of lightness and clarity, and as we have seen, the Sanskrit for clarity is prakāśa—“that which shines.” Thus, śauca is fundamentally linked to the cultivation of sattva. In popular culture, caring for oneself and treating oneself kindly can easily be equated with sensual indulgence. In deciding what really qualifies as śauca the acid test should be: does it cultivate sattva in our bodies and minds? Does it encourage a feeling of physical, emotional and mental lightness and clarity? We are not against chocolate brownies (in moderation!), but honestly: do they encourage sattva? Śauca requires a degree of discrimination and often, self-discipline.

a has the qualities of lightness and clarity, and as we have seen, the Sanskrit for clarity is prakāśa—“that which shines.” Thus, śauca is fundamentally linked to the cultivation of sattva. In popular culture, caring for oneself and treating oneself kindly can easily be equated with sensual indulgence. In deciding what really qualifies as śauca the acid test should be: does it cultivate sattva in our bodies and minds? Does it encourage a feeling of physical, emotional and mental lightness and clarity? We are not against chocolate brownies (in moderation!), but honestly: do they encourage sattva? Śauca requires a degree of discrimination and often, self-discipline.

Peter Hersnack told a memorable story concerning śauca.3 There were two children in a family, one of whom was seriously ill. The family rallied around the sick child, who became the focus of the parents' attention and the center of family life. As this situation continued, the child who was well became more withdrawn and alienated, almost invisible. In the last hundred years or so, yoga has become increasingly associated with maintaining one's health and youthfulness, and yoga therapy has become popular for addressing many physical or mental conditions. It is certainly true that yoga and āyurveda share many common principles, and yoga may be a very effective therapeutic tool, but it is important to not lose sight of the goal. For yoga to truly address the fundamental causes of human suffering we must explore the deeper nature of ourselves and that potential. Śauca needs to care for our “sick child” but also, and perhaps most importantly, care and nurture our “well child.” We must be careful we do not become so fixated on our niggles and problems that we lose sight of our possibilities and potentials. “Caring for ourselves as if for another” importantly includes caring for the part of us that is not problematic. As we age and physical challenges arise, it is easy to become preoccupied with, and increasingly defined by, one's problems. Śauca takes us beyond this.

Śauca is unusual among the yama and niyama in that it has two sūtras discussing its fruits. The first (YS 2.40) discusses outer śauca, concerned principally with the body. This difficult sūtra can easily be misinterpreted. Two results are given, svā ga jugupsā and parair asa

ga jugupsā and parair asa sarga

sarga . The first is usually translated as a “distaste” or “disgust” for the body (svā

. The first is usually translated as a “distaste” or “disgust” for the body (svā ga means “one's own limbs”). There was certainly a current in Indian thought at the time of the Yoga Sūtra that viewed the body in a negative light, as something to be defeated, an obstacle to spiritual pursuits. However, we consider this to be unhelpful. It is true that attending to the needs of the body takes considerable time and energy, and ultimately, the body is subject to decay. In this sense, we could say that we become aware of the limitations of the body and while attending to it, we should not become overly preoccupied with or attached to it.

ga means “one's own limbs”). There was certainly a current in Indian thought at the time of the Yoga Sūtra that viewed the body in a negative light, as something to be defeated, an obstacle to spiritual pursuits. However, we consider this to be unhelpful. It is true that attending to the needs of the body takes considerable time and energy, and ultimately, the body is subject to decay. In this sense, we could say that we become aware of the limitations of the body and while attending to it, we should not become overly preoccupied with or attached to it.

The root of the word jugupsā is gup, meaning “to protect” or “keep secret.” We can understand śauca of the body as a means to protect the body, to look after it and, on a deeper level, to protect us from the body by minimizing the distraction that it causes (because it is functioning as well as possible). A deeper understanding still suggests that by realizing the limitations and frailties of the body, we do not get caught up in it. Krishnamacharya was quoted as saying, “What use is the sword of knowledge if the bearer is too weak to wield it?”4 Although the mind can transcend the body's pain, it is not easy to maintain our clarity when there is a lot of physical discomfort. As we have seen in Chapter 4, the sūtra heya du

du kham anāgata

kham anāgata (YS 2.16) encourages us to avoid the pain and distress that can be avoided and outer śauca has an important role in this.

(YS 2.16) encourages us to avoid the pain and distress that can be avoided and outer śauca has an important role in this.

The other fruit of outer śauca, parair asa sarga, means “lack of contact with others” and it addresses the effect of others and our environment upon us. Śauca here encourages us to favor satsa

sarga, means “lack of contact with others” and it addresses the effect of others and our environment upon us. Śauca here encourages us to favor satsa ga—association that is supportive and consistent with our goals. Although there have been yogis who have lived and practiced anonymously in the most challenging conditions, often yogis have favored solitude or living within communities of like-minded souls. We are prone to be influenced by others and absorb their qualities. While life often requires us to engage in difficult situations (much compassionate activity involves working with difficult people or challenging situations and environments), it is not easy to maintain one's balance in such situations and we should be mindful of the toll it takes. Part of the practice of śauca is to cleanse oneself of the negative effects of such circumstances, and also to explore choices that reduce or eliminate situations or relationships that are unnecessarily toxic.

ga—association that is supportive and consistent with our goals. Although there have been yogis who have lived and practiced anonymously in the most challenging conditions, often yogis have favored solitude or living within communities of like-minded souls. We are prone to be influenced by others and absorb their qualities. While life often requires us to engage in difficult situations (much compassionate activity involves working with difficult people or challenging situations and environments), it is not easy to maintain one's balance in such situations and we should be mindful of the toll it takes. Part of the practice of śauca is to cleanse oneself of the negative effects of such circumstances, and also to explore choices that reduce or eliminate situations or relationships that are unnecessarily toxic.

In his commentary concerning outer śauca, Vyāsa gives some examples, such as discipline about food and the performance of rituals of purification. For Krishnamacharya and Desikachar too, diet was very important because it influences both our body and our state of mind. The inclusion of ritual is also interesting here. Because ritual purity is such an important concern of traditional Brahmanical society, it would be easy to dismiss this aspect of śauca as culturally specific. But in the modern therapy world, the need for supervision to help unburden the therapist from the negative influences of clients and their stories is well acknowledged. Perhaps many of us have the need for some kind of purification from difficult situations in our lives.

yoga sutra 2.41

sattva-śuddhi saumanasya ekāgrya indriyajaya ātma-darśana-yogyatvāni ca

And (the development) of a clear mind, positive attitude, focus, control of the senses and a fitness for a deep experience of the Self

This sūtra presents five fruits of inner śauca:

1 sattva-śuddhi—a clear mind

2 saumanasya—positive attitude

3 ekāgrya—focus

4 indriya-jaya—control of the senses

5 ātma-darśana-yogyatva—fitness for a deep experience of the Self

As with many of the other lists in the Yoga Sūtra, the first can be seen as the foundation and most important, and the last also has a special significance. The first, sattva-śuddhi, suggests that through śauca we can promote sattva in our minds. This emphasizes the essential qualification for śauca: that it cultivates and inclines us towards sattva. And in a similar way to ahi sā in relation to the other yama, we can see the other fruits of inner śauca as arising from, and in some sense qualifying and enhancing, sattva-śuddhi.

sā in relation to the other yama, we can see the other fruits of inner śauca as arising from, and in some sense qualifying and enhancing, sattva-śuddhi.

The second fruit is saumanasya, a cheerful or positive attitude. The opposite, daurmanasya (literally “bad mind”), is negative or pessimistic thinking. Daurmanasya always involves excessive tamas, which contributes to a distorted view, and then further tamas which contributes to a heavy or depressed state. Rajas, leading to anxiety or neurotic or obsessive thinking, may also be out of balance. Saumanasya requires the light, clear and spacious qualities of sattva which give rise to clarity of thinking.

One-pointedness (ekāgrya) is the third fruit. This is a natural consequence of the reduction of rajas and tamas and the cultivation of sattva. Ekāgrya is the level of citta v tti nirodha that we can actively practice and cultivate. The necessity for sattva in order to direct the mind with clarity and stability is emphasized throughout the text and equated with the highest states of yoga. In this sense, all effective yoga practice is śauca: the cultivation of sattva.

tti nirodha that we can actively practice and cultivate. The necessity for sattva in order to direct the mind with clarity and stability is emphasized throughout the text and equated with the highest states of yoga. In this sense, all effective yoga practice is śauca: the cultivation of sattva.

The Sanskrit term for the senses is indriya.5 A recurrent theme in the Indian spiritual tradition is how the senses can easily become the masters, keeping us enslaved to the sensations they provide. This is the opposite of their ideal role as servants of the Self. For the senses to bind us, rajas and tamas must be dominant in the mind. Rajas stimulates the desire for sensual pleasure and tamas deludes us into believing that the indriya are masters, not servants. Sattva is the antidote to this situation, providing the clarity to understand the true nature of the indriya and to use them wisely. Thus, the fourth of the fruits of śauca is indriya jaya: mastery of the senses. Here, we use the senses with clarity and skill—to nurture, rather than imprison us.

The last of the fruits of śauca, like the last of the yama, takes us beyond the immediate concerns of the others. It is ātma darśana yogyatva: making us fit for a vision of the true self. The domain of śauca is prak ti, that which is subject to the gu

ti, that which is subject to the gu a and therefore can be purified. The Self, ātma, cannot be purified because it is beyond the gu

a and therefore can be purified. The Self, ātma, cannot be purified because it is beyond the gu a. Here what is suggested is a vision or realization of the Self—and this experience can only happen in the mind. Ironically, the mind itself is the means to realize the truth beyond the mind. We work with the mind to transcend it (or at least to realize its true nature and role: as a servant of its lord). What are the conditions in the mind that make such a realization possible? The answer, of course, is a prevalence of sattva gu

a. Here what is suggested is a vision or realization of the Self—and this experience can only happen in the mind. Ironically, the mind itself is the means to realize the truth beyond the mind. We work with the mind to transcend it (or at least to realize its true nature and role: as a servant of its lord). What are the conditions in the mind that make such a realization possible? The answer, of course, is a prevalence of sattva gu a; we might say that sattva is the support for the experience of puru

a; we might say that sattva is the support for the experience of puru a or ātma. This final aspect of śauca elevates it to a principle of the highest importance as it is an essential support for the deepest of experiences. Although this might sound rather abstract, in fact it has great practical relevance. Even the relative cultivation of sattva (moving from a position of less sattva to more sattva) creates the conditions for deeper experiences and realizations. The principal is quite universal.

a or ātma. This final aspect of śauca elevates it to a principle of the highest importance as it is an essential support for the deepest of experiences. Although this might sound rather abstract, in fact it has great practical relevance. Even the relative cultivation of sattva (moving from a position of less sattva to more sattva) creates the conditions for deeper experiences and realizations. The principal is quite universal.

yoga sutra 2.42

sa to

to ād anuttama

ād anuttama sukha-lābha

sukha-lābha

From contentment arises a happiness which is unexcelled

Sa to

to a means “contentment,” and in particular a contentment that comes from within. It is linked inwards to the spiritual aspect of ourselves (as distinct from śauca, which is more concerned with prak

a means “contentment,” and in particular a contentment that comes from within. It is linked inwards to the spiritual aspect of ourselves (as distinct from śauca, which is more concerned with prak ti). Developing sa

ti). Developing sa to

to a gives rise to sukha anuttama

a gives rise to sukha anuttama , a happiness that is unexcelled. This is beyond normal sukha, which has an opposite, du

, a happiness that is unexcelled. This is beyond normal sukha, which has an opposite, du kha. It is beyond all qualities such as pleasure and suffering, or happiness that arises from external conditions. When discussing the kleśa we met rāga (desire) and dve

kha. It is beyond all qualities such as pleasure and suffering, or happiness that arises from external conditions. When discussing the kleśa we met rāga (desire) and dve a (aversion). These result in a temporary, ordinary level of happiness when a desire is fulfilled or something successfully avoided, or an experience of du

a (aversion). These result in a temporary, ordinary level of happiness when a desire is fulfilled or something successfully avoided, or an experience of du kha when they are not. But kleśa, by definition, ultimately give rise to suffering. Thus any satisfaction arising from kleśa is short-lived and unsatisfactory. The sukha arising from sa

kha when they are not. But kleśa, by definition, ultimately give rise to suffering. Thus any satisfaction arising from kleśa is short-lived and unsatisfactory. The sukha arising from sa to

to a is of a completely different order and hence the qualification that it is unsurpassed: anuttama

a is of a completely different order and hence the qualification that it is unsurpassed: anuttama .

.

So, what could be the source of such sukha? The answer is realization of puru a. In the Upani

a. In the Upani ads,6 the nature of the Self is said to be satcitānanda—real, conscious and blissful. Elsewhere, including in the Yoga Sūtra, we understand that the Self is beyond qualities (nirgu

ads,6 the nature of the Self is said to be satcitānanda—real, conscious and blissful. Elsewhere, including in the Yoga Sūtra, we understand that the Self is beyond qualities (nirgu a). This gives us an apparent contradiction until we realize that although the Self is beyond qualities, an experience of it must arise within the mind, which is subject to the gu

a). This gives us an apparent contradiction until we realize that although the Self is beyond qualities, an experience of it must arise within the mind, which is subject to the gu a. Thus sa

a. Thus sa to

to a becomes possible as our link to what is inside becomes stronger. The support for such a realization is sattva, the result of śauca. Hence śauca here also functions as a foundation for sa

a becomes possible as our link to what is inside becomes stronger. The support for such a realization is sattva, the result of śauca. Hence śauca here also functions as a foundation for sa to

to a.

a.

As embodied beings, our minds and the world we live in are subject to all three gu a. Diligently cultivating sattva will not necessarily stop the domination of the other gu

a. Diligently cultivating sattva will not necessarily stop the domination of the other gu a at times. But if we trust our connection to our deepest Being, beyond the gu

a at times. But if we trust our connection to our deepest Being, beyond the gu a, a special type of contentment arises. According to yoga, prā

a, a special type of contentment arises. According to yoga, prā a is the manifestation of puru

a is the manifestation of puru a, or Life within us; prā

a, or Life within us; prā a is to Life what sunlight is to the sun. We experience prā

a is to Life what sunlight is to the sun. We experience prā a as a feeling of being alive, even when we are in pain, despair or depression. Prā

a as a feeling of being alive, even when we are in pain, despair or depression. Prā a is thus the sign that puru

a is thus the sign that puru a is present. As a practical definition, we could understand sa

a is present. As a practical definition, we could understand sa to

to a as a contentment that arises from feeling that one is carried by Life from inside, irrespective of what is happening, or how we are feeling from moment to moment. Cultivating sattva is certainly a means to developing our understanding and strengthening our connection to the deeper parts of ourselves. But real sa

a as a contentment that arises from feeling that one is carried by Life from inside, irrespective of what is happening, or how we are feeling from moment to moment. Cultivating sattva is certainly a means to developing our understanding and strengthening our connection to the deeper parts of ourselves. But real sa to

to a is tested by our experience of life in all its forms. Sukha anuttama

a is tested by our experience of life in all its forms. Sukha anuttama gives us an ability to be with what is, whatever its form or qualities; it is not simply the bliss of deep meditation or idyllic circumstances.

gives us an ability to be with what is, whatever its form or qualities; it is not simply the bliss of deep meditation or idyllic circumstances.

It is natural to want to make the best of our lives. Too often, however, this becomes an obsession—an endless search for the perfect relationship, perfect clothes, perfect social life, perfect family, etc. Sa to

to a is accepting that we have a good enough life. This is not an invitation to be complacent or without aspiration, but to take the pressure off expectation. Life is a gift which arises from inside, whatever form it may take, and there is profound contentment that can come from truly allowing it to be our fundamental support and refuge, whether in tears or laughter, joy or despair. Life is our common denominator, for as long as we have the privilege of being alive.

a is accepting that we have a good enough life. This is not an invitation to be complacent or without aspiration, but to take the pressure off expectation. Life is a gift which arises from inside, whatever form it may take, and there is profound contentment that can come from truly allowing it to be our fundamental support and refuge, whether in tears or laughter, joy or despair. Life is our common denominator, for as long as we have the privilege of being alive.

The principles of viniyoga and vinyāsa krama invite us to start where we are and progress in steps. Strategies to develop contentment at a practical level can be very useful. Cultivating gratitude in our lives and noticing the richness and delightfulness in many simple things, such as nature, can be a powerful antidote to everyday dissatisfaction. Taking more time over small things, and cultivating simplicity in life, can give us space to appreciate what we have. We may discover that we already have much more sukha available to us in our lives than we ever thought possible. However, we should not confuse this with sukha anuttama , which arises from inside and is independent of our success or failure, sickness or health, flexibility or stiffness.

, which arises from inside and is independent of our success or failure, sickness or health, flexibility or stiffness.

Sa to

to a is not simply the appearance of benevolent beatitude—a common mask in yoga circles. Sa

a is not simply the appearance of benevolent beatitude—a common mask in yoga circles. Sa to

to a is linked to satya (truth)—it requires authenticity and is based on both the reality of where life comes from, and the reality of the form that life is taking (i.e., what is happening), without illusions and free of any expectation that it should be different.

a is linked to satya (truth)—it requires authenticity and is based on both the reality of where life comes from, and the reality of the form that life is taking (i.e., what is happening), without illusions and free of any expectation that it should be different.

Like vairāgya, sa to

to a can be misunderstood as a kind of armor that protects us from the world. We might think that contentment is possible only if we withdraw and remain disengaged. Here we cannot be threatened, as if we are living in an ivory tower. But this may well be a fragile state, and also a tragic one if we value the process and richness of life. True sa

a can be misunderstood as a kind of armor that protects us from the world. We might think that contentment is possible only if we withdraw and remain disengaged. Here we cannot be threatened, as if we are living in an ivory tower. But this may well be a fragile state, and also a tragic one if we value the process and richness of life. True sa to

to a gives us the contentment to be in life while connected to something beyond it. It gives us the freedom and joy to be really touched by life and death without being destroyed by either. This does not mean that we should not make choices about how we live and what we expose ourselves to—life need not be an endurance test! But importantly, sa

a gives us the contentment to be in life while connected to something beyond it. It gives us the freedom and joy to be really touched by life and death without being destroyed by either. This does not mean that we should not make choices about how we live and what we expose ourselves to—life need not be an endurance test! But importantly, sa to

to a (indeed, yoga as a whole) should not become an excuse to hide from life.

a (indeed, yoga as a whole) should not become an excuse to hide from life.

Sādhana: Looking after ourselves

The scope of yoga, and yama and niyama in particular, is broad, covering every aspect of our lives. In very physically oriented approaches there can be a tendency to apply the eight limbs, including yama and niyama, exclusively to the physical sphere, presenting yoga as a purely mat-based practice system. This distorts and reduces yoga to a fraction of its intended scope. With this said, however, we can apply the principles of yama and niyama to our physical practice just as we can to all other aspects of our lives, and here we would like to discuss “taking care” in our practice.

Over its long and varied history, the yoga tradition has explored all manner of physical and meditative practices, which in some cases have pushed the physical limits of the body to the extreme. A common Ha ha Yoga practice, for example, involved cutting the frenum of the tongue allowing it to be unnaturally extended and turned back in the mouth in a practice known as khecarī. Krishnamacharya was strongly against such practices: in accordance with the fundamental principle of ahi

ha Yoga practice, for example, involved cutting the frenum of the tongue allowing it to be unnaturally extended and turned back in the mouth in a practice known as khecarī. Krishnamacharya was strongly against such practices: in accordance with the fundamental principle of ahi sā, he believed yoga practice should not harm the body and certainly should not include its deliberate mutilation. Indeed, he was against all practices that introduced foreign substances into the body, even with the purpose of purification, believing that air and fire (in the sense of breath and the “internal fire,” agni) were sufficient to cleanse the system.7

sā, he believed yoga practice should not harm the body and certainly should not include its deliberate mutilation. Indeed, he was against all practices that introduced foreign substances into the body, even with the purpose of purification, believing that air and fire (in the sense of breath and the “internal fire,” agni) were sufficient to cleanse the system.7

We have defined śauca as “taking care of ourselves as if of another” and linked śauca to the cultivation of sattva. So the question is how to ensure that our practice both does us no harm on the one hand, and on the other, supports us in taking care of ourselves. As ever, we must bear in mind the process of pari āma (change) that inevitably bears upon our bodies as we mature and age. The sat viniyoga (wholesome application) of yoga must ensure that the practice remains both supportive of us and certainly not injurious to our well-being.

āma (change) that inevitably bears upon our bodies as we mature and age. The sat viniyoga (wholesome application) of yoga must ensure that the practice remains both supportive of us and certainly not injurious to our well-being.

As with most alternative health practitioners, yoga teachers will sometimes hear their students express surprise (and often disappointment) if they become ill. “You shouldn't have a cold—you're a yoga teacher!” they might say. These projections can take other forms too: “Do you ever get stressed?” or “Are you ever angry?” It's worth realizing that one of the reasons that many of us took up yoga is because there was something fundamental in our lives that we felt needed addressing—yoga is there to help us deal with our “issues”!

While it is true that yoga practice done well and appropriately optimizes good health, both physical and mental, we will all have our ups and downs. This is only natural. It is also true that sometimes illness can be unexpected and perplexing; it seemed unbelievable that Desikachar, a truly focused and inspiring teacher and practitioner of yoga, should start suffering from dementia at a comparatively early age.8 Similarly, Peter Hersnack died very quickly from an aggressive form of cancer in 2016 in his late sixties. Yoga is not a universal inoculation from illness or death; it can, however, help us to deal with them as they arise.

It is easy to become disillusioned or disappointed if we fall ill or find life a struggle, and we can make our conditions even worse if we feel guilty or unworthy as well. If śauca is “to treat ourselves as we would another,” it is important that we extend compassion to ourselves when we need to, and acknowledge our vulnerabilities, imperfections and weaknesses. This is not the same as indulging them—it is treating ourselves with care.

to

to a

aEvolutionary psychologists have frequently pointed out that we are hard-wired to look for danger and consequently we can be hypervigilant towards anything untoward. Dangers are a threat, and they need to be noticed. We also perceive faults far more acutely than we do successes—a single word of criticism can sting amongst a sea of praise. When things are going well we often take them for granted and do not notice them. As the old soul song says: “You don't miss your water till your well runs dry!” It is all too easy to develop amnesia for all the positives in our lives, while maintaining and harboring grudges for far too long. We forget what we should remember, and remember what we should forget. Because this is in some ways natural, we need to work at cultivating its opposite—to notice the good and to take in what will nourish us, rather than what will eventually poison us.

We have found a simple practice, done at the end of āsana or prā āyāma, to be extremely effective.9 We sit down and let the breath and thoughts relax. Then, as we slowly breathe in, we allow somebody—anybody—to enter into our minds. As we then exhale, we offer them thanks—for whatever. On the next breath, we wait to see who will appear, whom we can next offer thanks to. It may be the same person, and of course certain people in our lives may appear more regularly than others. But what is most interesting is that completely surprising people appear—friends or acquaintances we have not thought about for years: the boy who sat next to you in school when you were five, or a stranger you smiled at on a bus. It doesn't have to be profound, it is simply a gesture of connection and gratitude and it works. On many occasions Ranju has smiled as he practices this, remembering and being with certain people in his life—even for just a breath. It is a simple and accessible practice that helps us cultivate a profound sense of connection and contentment—and it need take as few as twelve breaths or so.

āyāma, to be extremely effective.9 We sit down and let the breath and thoughts relax. Then, as we slowly breathe in, we allow somebody—anybody—to enter into our minds. As we then exhale, we offer them thanks—for whatever. On the next breath, we wait to see who will appear, whom we can next offer thanks to. It may be the same person, and of course certain people in our lives may appear more regularly than others. But what is most interesting is that completely surprising people appear—friends or acquaintances we have not thought about for years: the boy who sat next to you in school when you were five, or a stranger you smiled at on a bus. It doesn't have to be profound, it is simply a gesture of connection and gratitude and it works. On many occasions Ranju has smiled as he practices this, remembering and being with certain people in his life—even for just a breath. It is a simple and accessible practice that helps us cultivate a profound sense of connection and contentment—and it need take as few as twelve breaths or so.