yoga sutra 2.16

heya du

du kham anāgata

kham anāgata

Avoid future suffering

Here Patañjali asserts our agency: we do have some element of control and volition, and we are not simply passive victims of fate. While it is impossible to control all future events and experiences, we are at least able to consider how our current actions and thoughts impact on our future. Heya means “that which is to be avoided” while anāgata means “yet to come.” This sūtra is about living in a way that minimizes future suffering (du

means “yet to come.” This sūtra is about living in a way that minimizes future suffering (du kha). The Bhagavad Gītā defines yoga as “skill in action”—we practice yoga by most elegantly engaging with our experiences as they arise. By reducing our tendencies to compound our problems, this sort of skillful living helps us to reduce the suffering yet to come.

kha). The Bhagavad Gītā defines yoga as “skill in action”—we practice yoga by most elegantly engaging with our experiences as they arise. By reducing our tendencies to compound our problems, this sort of skillful living helps us to reduce the suffering yet to come.

Unfortunately, many situations are made considerably worse by inappropriate coping mechanisms, unthinking reactions or redundant habits. Like a polluting, un-tuned engine whose carbon emissions are high, unskillful actions leave unwanted residue which continues to reverberate, causing more confusion, delusion and suffering both for ourselves and for others. Can we reduce our “karmic emissions” to a level whereby we tread lightly on this Earth and leave it—and our relationships—in a better place?

kha and its causes

kha and its causes

yoga sutra 2.15

pari āma-tāpa-sa

āma-tāpa-sa skāra-du

skāra-du khair gu

khair gu av

av tti-virodhāc ca du

tti-virodhāc ca du kham eva sarva

kham eva sarva vivekina

vivekina

For those with discrimination, suffering is to be found everywhere due to change (pari āma), pain (tāpa) and habits (sa

āma), pain (tāpa) and habits (sa skāra) and also because the mind is in constant flux due to the gu

skāra) and also because the mind is in constant flux due to the gu a

a

The starting point for all classical Indian philosophy is du kha, which is often translated as “suffering.” But the way our suffering is described and resolved in Indian philosophy is highly nuanced; indeed “suffering” is too broad a term to do justice to the Sanskrit, and its resolution is not simply anesthetizing ourselves to all pain. The word itself is made up of two syllables: dus1 and kha. When used as a prefix, dus means “unfavorable,” “unpleasant” or “bad.” And the syllable kha represents the element of space; here, specifically, the space in our heart, or emotional body. It is said that when energy does not circulate well and we feel “stuck” we experience du

kha, which is often translated as “suffering.” But the way our suffering is described and resolved in Indian philosophy is highly nuanced; indeed “suffering” is too broad a term to do justice to the Sanskrit, and its resolution is not simply anesthetizing ourselves to all pain. The word itself is made up of two syllables: dus1 and kha. When used as a prefix, dus means “unfavorable,” “unpleasant” or “bad.” And the syllable kha represents the element of space; here, specifically, the space in our heart, or emotional body. It is said that when energy does not circulate well and we feel “stuck” we experience du kha because there is a blockage. Such blockages arise due to past actions, residue that has accumulated and now impedes free flow. One way of resolving this du

kha because there is a blockage. Such blockages arise due to past actions, residue that has accumulated and now impedes free flow. One way of resolving this du kha is to cultivate a feeling of spaciousness (in Sanskrit this is called sukha) by removing such blockages whether they are physical, emotional or psychological.

kha is to cultivate a feeling of spaciousness (in Sanskrit this is called sukha) by removing such blockages whether they are physical, emotional or psychological.

The relationship between the experience of du kha and our past actions is very important to understand. These actions include our thoughts and emotions as well as our physical actions, because the way we think and feel now is dependent on the way we thought and felt yesterday, and this colors our experience of current events. Actions that we have taken in the past will naturally have consequences, favorable or otherwise, in the present and future. But equally, the psychology behind those actions, the motives and thought processes, will impact on how we relate to our lives as they unfold. Are we bitter, resigned, carefree, indifferent, happy or lazy? The residue of thoughts and actions (karma-āśaya) are the seeds for future experiences. This is why karma (which means both an action and also that action's consequences) is such a central theme of classical Indian philosophy; we cannot understand du

kha and our past actions is very important to understand. These actions include our thoughts and emotions as well as our physical actions, because the way we think and feel now is dependent on the way we thought and felt yesterday, and this colors our experience of current events. Actions that we have taken in the past will naturally have consequences, favorable or otherwise, in the present and future. But equally, the psychology behind those actions, the motives and thought processes, will impact on how we relate to our lives as they unfold. Are we bitter, resigned, carefree, indifferent, happy or lazy? The residue of thoughts and actions (karma-āśaya) are the seeds for future experiences. This is why karma (which means both an action and also that action's consequences) is such a central theme of classical Indian philosophy; we cannot understand du kha without some appreciation of karma.

kha without some appreciation of karma.

The philosophy of Sā khya, sometimes seen as the sister to Patañjali's Yoga Sūtra, was codified roughly 1,600 years ago by Īśvara K

khya, sometimes seen as the sister to Patañjali's Yoga Sūtra, was codified roughly 1,600 years ago by Īśvara K

a in his classic work, Sā

a in his classic work, Sā khya Kārikā (“Verses on Sā

khya Kārikā (“Verses on Sā khya”). The text starts by stating that the purpose of Sā

khya”). The text starts by stating that the purpose of Sā khya is the resolution of three types of du

khya is the resolution of three types of du kha. The three types are understood to be:

kha. The three types are understood to be:

His solution to the problem of du kha is discriminative knowledge (which is called viveka in the Yoga Sūtra): the cultivation of insight that cuts through illusions and sets us free. Only this discriminative knowledge is a certain cure for du

kha is discriminative knowledge (which is called viveka in the Yoga Sūtra): the cultivation of insight that cuts through illusions and sets us free. Only this discriminative knowledge is a certain cure for du kha, he says; all other remedies are subject to uncertainty or decay.2 Careful investigation into both the nature of ourselves and the nature of all that surrounds us is the way out of the maze of du

kha, he says; all other remedies are subject to uncertainty or decay.2 Careful investigation into both the nature of ourselves and the nature of all that surrounds us is the way out of the maze of du kha. Thus for Īśvara K

kha. Thus for Īśvara K

a, the only surefire resolution is philosophical enquiry and the gradual reshaping of our habitual understanding of the world. This necessitates a new way of thinking and being.

a, the only surefire resolution is philosophical enquiry and the gradual reshaping of our habitual understanding of the world. This necessitates a new way of thinking and being.

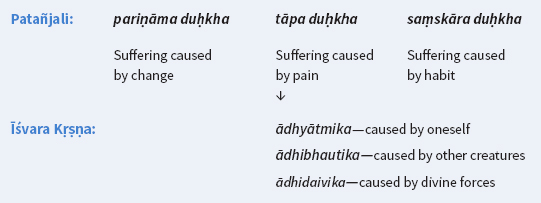

In YS 2.15, Patañjali also divides du kha into three types, but they are presented in a slightly different way than in the Sā

kha into three types, but they are presented in a slightly different way than in the Sā khya Kārikā. Patañjali says that du

khya Kārikā. Patañjali says that du kha is inevitable because of the fluctuating nature of the gu

kha is inevitable because of the fluctuating nature of the gu a.3 As we have seen, the gu

a.3 As we have seen, the gu a are the essence of not just the entire phenomenal world, but most importantly, the very nature of our minds. When our actions are strongly colored by excess rajas or tamas, and are thereby characterized by inappropriate desire and agitation (rajas) or by dullness, delusion and rigidity (tamas), then their consequences will have some of these qualities too.

a are the essence of not just the entire phenomenal world, but most importantly, the very nature of our minds. When our actions are strongly colored by excess rajas or tamas, and are thereby characterized by inappropriate desire and agitation (rajas) or by dullness, delusion and rigidity (tamas), then their consequences will have some of these qualities too.

The first type of du kha Patañjali refers to is called pari

kha Patañjali refers to is called pari āma du

āma du kha. The dance of the gu

kha. The dance of the gu a ensures that nothing is permanent; change (pari

a ensures that nothing is permanent; change (pari āma) means we suffer from pari

āma) means we suffer from pari āma du

āma du kha—the emotional constriction that arises when what we would like to remain, changes. A beautiful ripe fruit will decay and become rotten; an enjoyable meal of excess can result in tummy problems or a headache the next day. Everything moves, sometimes slowly and sometimes very quickly, and even moments of great beauty and happiness are tinged with the poignancy of knowing that they will end. And of course, our minds also change—sometimes we are clear and at others, consumed by anxiety, worry or remorse and regret.

kha—the emotional constriction that arises when what we would like to remain, changes. A beautiful ripe fruit will decay and become rotten; an enjoyable meal of excess can result in tummy problems or a headache the next day. Everything moves, sometimes slowly and sometimes very quickly, and even moments of great beauty and happiness are tinged with the poignancy of knowing that they will end. And of course, our minds also change—sometimes we are clear and at others, consumed by anxiety, worry or remorse and regret.

While pari āma du

āma du kha is the result of change, its flipside, sa

kha is the result of change, its flipside, sa skāra du

skāra du kha, is the result of our tendency to create and maintain habitual ways of thinking, feeling and acting. Our minds love to create habits, to move down well-worn tracks of thinking and being. These patterns of habit are called sa

kha, is the result of our tendency to create and maintain habitual ways of thinking, feeling and acting. Our minds love to create habits, to move down well-worn tracks of thinking and being. These patterns of habit are called sa skāra, and our sa

skāra, and our sa skāra will naturally create certain consequences, as thoughts solidify into actions and actions solidify into our ways of living. The repetition of small sa

skāra will naturally create certain consequences, as thoughts solidify into actions and actions solidify into our ways of living. The repetition of small sa skāra can have big consequences as their effects accumulate.

skāra can have big consequences as their effects accumulate.

Of course not all sa skāra are small. We can say that any type of suffering which results from our patterning and our habits, however large or trivial, is sa

skāra are small. We can say that any type of suffering which results from our patterning and our habits, however large or trivial, is sa skāra du

skāra du kha. It is also worth remembering that sa

kha. It is also worth remembering that sa skāra du

skāra du kha can arise out of simply being stuck in a habit that is no longer appropriate. Where once a strategy worked, now it has become redundant and is causing unhappiness—either to us or to others.

kha can arise out of simply being stuck in a habit that is no longer appropriate. Where once a strategy worked, now it has become redundant and is causing unhappiness—either to us or to others.

The third type of du kha to which Patañjali refers is tāpa du

kha to which Patañjali refers is tāpa du kha. Tāpa comes from the root tap, meaning “to heat.” It is the suffering which arises from pain, from the myriad forms of discomfort, be they physical (standing on a nail, being bitten by an animal, being too hot or too cold) or emotional/psychological (being thwarted, unfulfilled, rejected, bored, angry). Thus tāpa du

kha. Tāpa comes from the root tap, meaning “to heat.” It is the suffering which arises from pain, from the myriad forms of discomfort, be they physical (standing on a nail, being bitten by an animal, being too hot or too cold) or emotional/psychological (being thwarted, unfulfilled, rejected, bored, angry). Thus tāpa du kha comes from the pain arising from our senses and their connection to our minds, particularly related to our desires and expectations. We can subdivide tāpa du

kha comes from the pain arising from our senses and their connection to our minds, particularly related to our desires and expectations. We can subdivide tāpa du kha into the three types that are spoken about in the Sā

kha into the three types that are spoken about in the Sā khya Kārikā: ādhyātmika (caused by myself), ādhibhautika (caused by other creatures), and ādhidaivika (caused by divine forces).4 Patañjali elaborates the model of du

khya Kārikā: ādhyātmika (caused by myself), ādhibhautika (caused by other creatures), and ādhidaivika (caused by divine forces).4 Patañjali elaborates the model of du kha to include suffering arising from natural change and suffering arising from habitual patterns:

kha to include suffering arising from natural change and suffering arising from habitual patterns:

Can we avoid all du kha? It is impossible (and undesirable) to feel no pain as long as we are alive. Pain acts as a warning and is therefore often very useful. However, the du

kha? It is impossible (and undesirable) to feel no pain as long as we are alive. Pain acts as a warning and is therefore often very useful. However, the du kha we are considering is neither helpful nor desirable: it is the consequence of misunderstanding and unskillful action. Some du

kha we are considering is neither helpful nor desirable: it is the consequence of misunderstanding and unskillful action. Some du kha is conscious—we know that we are suffering—but at other times, it is unconscious. Often, we are unaware of what we are carrying, of how we think, and how this may color our perceptions. Many people anesthetize themselves with food, alcohol, drugs, sex or the internet as a way of remaining unconscious to their own suffering. Someone in a coma may well not experience the suffering of a conscious person, but Patañjali does not advocate shutting down to resolve pain. Instead he acknowledges there are certain types of du

kha is conscious—we know that we are suffering—but at other times, it is unconscious. Often, we are unaware of what we are carrying, of how we think, and how this may color our perceptions. Many people anesthetize themselves with food, alcohol, drugs, sex or the internet as a way of remaining unconscious to their own suffering. Someone in a coma may well not experience the suffering of a conscious person, but Patañjali does not advocate shutting down to resolve pain. Instead he acknowledges there are certain types of du kha that we can avoid and that it's very possible to not contribute to future frustrations and suffering by how we think and act right now. In essence: when you are in a hole, stop digging.

kha that we can avoid and that it's very possible to not contribute to future frustrations and suffering by how we think and act right now. In essence: when you are in a hole, stop digging.

Of course, there may be du kha coming to us which we can do nothing about; it would be naive to suggest that we can still retain feelings like pleasure and joy and yet totally eradicate all experience of pain. The loss of a loved one will naturally affect us; however, the host of thoughts that may go alongside any such event (“I wish it were otherwise,” “I should have done this or that,” “What is to become of me?” and so on) will be significantly reduced as we refine our relationship to and experience of du

kha coming to us which we can do nothing about; it would be naive to suggest that we can still retain feelings like pleasure and joy and yet totally eradicate all experience of pain. The loss of a loved one will naturally affect us; however, the host of thoughts that may go alongside any such event (“I wish it were otherwise,” “I should have done this or that,” “What is to become of me?” and so on) will be significantly reduced as we refine our relationship to and experience of du kha. How we experience that pain, how we understand it, and how we most elegantly deal with it are the subjects at the heart of the yoga project. And in this quest, we must first ask: what is it that keeps producing du

kha. How we experience that pain, how we understand it, and how we most elegantly deal with it are the subjects at the heart of the yoga project. And in this quest, we must first ask: what is it that keeps producing du kha? What creates and maintains our suffering? We must turn our attention to hetu, the cause.

kha? What creates and maintains our suffering? We must turn our attention to hetu, the cause.

yoga sutra 2.17

dra

-d

-d śyayo

śyayo sa

sa yoga heya-hetu

yoga heya-hetu

Confusing the source of perception with the objects of perception is the root of suffering

In any experience, there is always the event itself and then our understanding of and reaction to the event. Some events are difficult, some are pleasant; however, the inability to distinguish an event from our reactions to it is the source of much unnecessary anguish.

Avidyā5 is this state of confusion. The term comprises “vidyā,” meaning “to know” (and is related to English words like “vision” and “video”), and the prefix “a,” which implies the opposite. However, although avidyā literally means “not knowing” or “not seeing,” it is more than simply willful blindness. We can be aware that we can't see something but when we are in a state of avidyā, we cannot see because we see something else. Our misunderstanding of a situation obscures a deeper reality. Avidyā is, therefore, by its very nature, unconscious: if we know we can't see something we are not in a state of avidyā, but one of conscious ignorance.

In YS 2.17, Patañjali goes even deeper into the notion of avidyā. He uses the term sa yoga almost synonymously with avidyā, saying that it is this sa

yoga almost synonymously with avidyā, saying that it is this sa yoga that is the cause (hetu) of our suffering. Whereas avidyā is more abstract and theoretical, sa

yoga that is the cause (hetu) of our suffering. Whereas avidyā is more abstract and theoretical, sa yoga is its embodied state; it is how we actually experience avidyā. Sa

yoga is its embodied state; it is how we actually experience avidyā. Sa yoga is “complete joining,” the bodily experience of mixed-up confusion, where we cannot make subtle distinctions because different elements are so enmeshed with each other that they look like a single event. In YS 2.17, Patañjali proposes that the inability to distinguish our thoughts and perceptions (d

yoga is “complete joining,” the bodily experience of mixed-up confusion, where we cannot make subtle distinctions because different elements are so enmeshed with each other that they look like a single event. In YS 2.17, Patañjali proposes that the inability to distinguish our thoughts and perceptions (d śya6) from a pure awareness utterly devoid of characteristics (dra

śya6) from a pure awareness utterly devoid of characteristics (dra

7) is at the very heart of the human predicament; this is the experience of avidyā at its most profound. By utterly identifying with the ephemeral contents of our consciousness, we mistake ourselves for the movie that we are in: the actor completely identifies with the role. As we have discussed in Chapter 2, this is our normal state and it dooms us to the endless cycle of mistakes and confusion that cause and maintain du

7) is at the very heart of the human predicament; this is the experience of avidyā at its most profound. By utterly identifying with the ephemeral contents of our consciousness, we mistake ourselves for the movie that we are in: the actor completely identifies with the role. As we have discussed in Chapter 2, this is our normal state and it dooms us to the endless cycle of mistakes and confusion that cause and maintain du kha.

kha.

Although sa yoga and avidyā are defined by Patañjali in profound philosophical terms, we find sa

yoga and avidyā are defined by Patañjali in profound philosophical terms, we find sa yoga and avidyā present in many everyday situations—for example, a beginner to yoga will often be unable to distinguish subtle movements in their own body and feel the whole body moving like a single block. In relationships too, we may confuse our thoughts and projections for another's—who we think we are is blurred with our fantasies about another person. Once we start noticing, we find sa

yoga and avidyā present in many everyday situations—for example, a beginner to yoga will often be unable to distinguish subtle movements in their own body and feel the whole body moving like a single block. In relationships too, we may confuse our thoughts and projections for another's—who we think we are is blurred with our fantasies about another person. Once we start noticing, we find sa yoga everywhere, and its resolution (clarifying and making appropriate distinctions) can bring about a feeling of freedom and space in many difficult situations. Once again, the most profound philosophical understandings of the Yoga Sūtra are also reflected in our everyday lived experience.

yoga everywhere, and its resolution (clarifying and making appropriate distinctions) can bring about a feeling of freedom and space in many difficult situations. Once again, the most profound philosophical understandings of the Yoga Sūtra are also reflected in our everyday lived experience.

tad-abhāvāt sa yoga-abhāvo hāna

yoga-abhāvo hāna tad-d

tad-d śe

śe kaivalya

kaivalya

As this tendency diminishes, the path to freedom develops

yoga sutra 2.25

The Roman philosopher Seneca famously said: “If one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favorable.” Having already analyzed how and why we suffer, and also what maintains this suffering, in YS 2.25 Patañjali presents his solution. As we have seen in Chapter 1, it is a popular notion that the goal of all yoga is union with the Divine, or a merging with a greater reality. Though this may be the case in some traditions, Patañjali's goal is rather different. His goal—indeed, he claims, the goal of all experience—is to disentangle oneself from the enmeshment and identification with the contents of our minds. He describes this in YS 2.25 as abhāva (removal) of sa yoga (enmeshment). Only through this practice of disentangling can one achieve true freedom or kaivalya.

yoga (enmeshment). Only through this practice of disentangling can one achieve true freedom or kaivalya.

Kaivalya literally translates as “alone-ness,” which on the surface may sound undesirable. However, what Patañjali means here is something positive: a freedom that arises from clarification between the essence of our Being and the projections of our minds. Instead of a merging, there is a differentiation; and although it may seem counterintuitive, it is this very differentiation which brings wholeness and a spaciousness. This is the “path to freedom,” the escape route (hāna). Enmeshment, sa yoga, is the opposite condition—where we are compromised and restricted, adding to our own suffering unconsciously.

yoga, is the opposite condition—where we are compromised and restricted, adding to our own suffering unconsciously.

yoga sutra 2.26

viveka-khyātir aviplavā hānopāya

Consistent discernment is the means to overcoming (sa yoga/avidyā)

yoga/avidyā)

There are many arenas in which we become entangled; each of our many facets and layers has the potential to become mired in avidyā. As sa yoga diminishes, the escape route (hāna

yoga diminishes, the escape route (hāna ) becomes clearer—through cultivation of viveka khyātir, discriminative awareness. In his famous a

) becomes clearer—through cultivation of viveka khyātir, discriminative awareness. In his famous a

ā

ā ga yoga, Patañjali describes eight arenas, and therefore eight types of practice, for the cultivation of this discriminative awareness. These practices are called upāya—the means. By addressing these many layers, from the interpersonal through to the subtlest aspects of mind, Patañjali ensures that the yoga project is systemic and multidimensional.

ga yoga, Patañjali describes eight arenas, and therefore eight types of practice, for the cultivation of this discriminative awareness. These practices are called upāya—the means. By addressing these many layers, from the interpersonal through to the subtlest aspects of mind, Patañjali ensures that the yoga project is systemic and multidimensional.

The eight limbs of yoga each address a different sort of sa yoga by cultivating spaciousness and clarity (sattva), at that level. Although some practices help to prepare for others by providing a stable support, they are not to be thought of as purely sequential but rather as developing simultaneously. The eight limbs of yoga provide support and give direction to each other so that the whole of our Being is increasingly experienced as light, free and spacious. Five of the eight limbs can be thought of as more external; these are discussed at the end of Chapter 2 of the Yoga Sūtra. The three which are seen as more internal are discussed at the beginning of Chapter 3 of the Yoga Sūtra.

yoga by cultivating spaciousness and clarity (sattva), at that level. Although some practices help to prepare for others by providing a stable support, they are not to be thought of as purely sequential but rather as developing simultaneously. The eight limbs of yoga provide support and give direction to each other so that the whole of our Being is increasingly experienced as light, free and spacious. Five of the eight limbs can be thought of as more external; these are discussed at the end of Chapter 2 of the Yoga Sūtra. The three which are seen as more internal are discussed at the beginning of Chapter 3 of the Yoga Sūtra.

ga

ga

āyāma refines our patterns of breathing and brings an extraordinary sensitivity to the flow of the breath and therefore our vital energy (prā

āyāma refines our patterns of breathing and brings an extraordinary sensitivity to the flow of the breath and therefore our vital energy (prā a). We explore this further in Chapter 10.

a). We explore this further in Chapter 10. ga

ga

ā focuses our attention on a single object, thereby cultivating mental stability and freedom from distraction.

ā focuses our attention on a single object, thereby cultivating mental stability and freedom from distraction.These last three limbs are collectively known as sa yama, the process of deepening a meditative practice. In their purest form, they are aimed at clarifying the distinction between the subtlest aspects of our consciousness and the pure empty awareness of puru

yama, the process of deepening a meditative practice. In their purest form, they are aimed at clarifying the distinction between the subtlest aspects of our consciousness and the pure empty awareness of puru a, and are therefore seen as advanced practices which require considerable stability and preparation. However, it is important not to dismiss sa

a, and are therefore seen as advanced practices which require considerable stability and preparation. However, it is important not to dismiss sa yama as too esoteric and therefore irrelevant. We explore some practical means of applying the principles of sa

yama as too esoteric and therefore irrelevant. We explore some practical means of applying the principles of sa yama in a simple and accessible way in Chapter 15.

yama in a simple and accessible way in Chapter 15.

Sādhana: Preparation and counterposture

In Chapter 3 we considered how the careful construction of a practice is fundamental to this approach. Any activity that requires a number of steps—cooking, painting or building—requires vinyāsa krama, the intelligent ordering of those steps. Two essential aspects of vinyāsa krama in āsana and prā āyāma are preparation and counterposture. In Sanskrit, pūrvā

āyāma are preparation and counterposture. In Sanskrit, pūrvā ga means “prior, preparatory parts”; it is the way we skillfully move towards a goal—it is the preparation. The word pratikriyāsana tells us something of the qualities of counterposture. Prati means “against,” or “opposite”; kriyā means “action” and so pratikriyāsana literally means “opposite action; posture.” Both pūrvā

ga means “prior, preparatory parts”; it is the way we skillfully move towards a goal—it is the preparation. The word pratikriyāsana tells us something of the qualities of counterposture. Prati means “against,” or “opposite”; kriyā means “action” and so pratikriyāsana literally means “opposite action; posture.” Both pūrvā ga and pratikriyā will help us “anticipate and avoid future suffering.”

ga and pratikriyā will help us “anticipate and avoid future suffering.”

ga: Preparation

ga: PreparationAs any painter and decorator will tell you, the quality of the preparation will define the quality of the end product. If you skimp on the preparation, even though a job may look good initially, it will deteriorate and show itself as second-rate soon enough. Similarly, the quality of the preparation in āsana and prā āyāma, in both the short and the long term, will define the quality and experience of a posture or technique. Without adequate preparation, a posture might not be well executed or integrated into the practice, and there will also be considerably greater chances of injury.

āyāma, in both the short and the long term, will define the quality and experience of a posture or technique. Without adequate preparation, a posture might not be well executed or integrated into the practice, and there will also be considerably greater chances of injury.

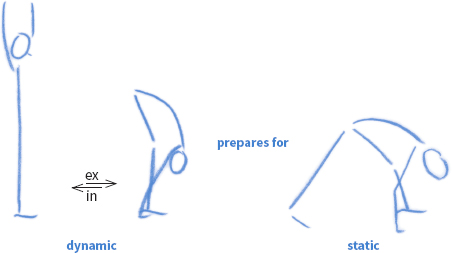

In some classes, students are taught to warm up prior to the yoga class. Desikachar always stated that the preparation should be part of the actual practice—there is no need for “pre-yoga warm-ups.” A useful principle is that we move from symmetrical, simple and dynamic postures to postures which are more complex. We slowly build up the intensity so that the body, breath and attention are all brought into an alignment and can thereby work together with maximum integrity.

For example, before we work with a static asymmetrical standing posture, we would prepare with some dynamic, symmetrical work which warms and mobilizes the body, engages our attention and prepares the breath for deep and slow breathing (fig 4.1).

As we have already seen in Chapter 3, the art of vinyāsa krama uses groups of postures to help prepare us for other groups. So standing postures will help to prepare us for more complex postures deeper in the practice; lying postures can help for seated postures (because they can safely stretch the backs of the legs). And in general, work with the body (āsana) will prepare us for static work with the breath (prā āyāma), which in turn prepares us for still seated meditation practices (dhyāna).

āyāma), which in turn prepares us for still seated meditation practices (dhyāna).

When our goal is a complex backbend, we should prepare with some gentler backbends; similarly, complex twists require simple twists as preparation. Generally speaking, standing backward bends (for example, the warrior, vīrabhadrāsana 1, fig 4.2), prepare us for more challenging prone backward bends (for example, the bow, dhanurāsana, fig 4.3).

prepares for

Similarly, standing forward bends (standing forward bend, uttānāsana; flank forward bend, pārśva uttānāsana, fig 4.4; and even the full squat, utka āsana) can prepare for seated forward bends (jānu śīr

āsana) can prepare for seated forward bends (jānu śīr āsana, fig 4.5 or paścimatānāsana) later in the practice.

āsana, fig 4.5 or paścimatānāsana) later in the practice.

prepares for

A seated twist (usually static, fig 4.7) will be helped by a standing twist (fig 4.6, often dynamic) and a lying twist (perhaps dynamic and static). Of course, not everyone will need the same amount of preparation: the body temperature, time of the day and many other variables will mean that sometimes more and sometimes less preparation is required.

prepares for

Desikachar was fond of telling a story—perhaps apocryphal—about when he was a young boy and was encouraged by his brothers to climb a palm tree for coconuts. He got up fine, but once up wasn't sure how to get down! This principle of understanding the route down, a sort of “opposite action,” is the basis of counterposture. In fact, Desikachar emphasized the importance of being able to perform a counterposture before attempting the main posture. An example of this is the shoulder stand (fig 4.8). Desikachar insisted that if you are unable to comfortably perform the counterposture—in this case dynamic cobra while sweeping the arms (fig 4.9)—then you should not attempt the posture. The counterposture thereby becomes a useful check: if you cannot do it properly, then do not attempt the posture.

requires

As we have seen, the theory of karma says that every action we take, including thoughts, has consequences. Some of these consequences may be positive, some less so. When we perform an āsana, the body and breath are challenged in particular ways and this affects the whole system. Not all of the effects will necessarily be positive; however, with adequate and sensitive counterposture, the negative effects of the posture can be minimised without “neutralizing” all of the positive effects. For example, after performing a number of seated forward bends, although the back has been lengthened and the back of the legs stretched, the hips have been closed for a long time and the lumbar lordosis flattened and reversed. Although we want to keep the feeling of having stretched the back of the body, we might also like to open and move the hips and also slightly arch the back to feel some sense of realignment. So counterpostures might include two-foot support, or kneeling forward bend.

Although there are some general principles, not everyone will need the same counterpostures. One person may need to address a hip stiffness; for someone else their neck may be the issue, or a problem in a shoulder or tightness in the back. As with so much in yoga, what is appropriate depends on the individual—and this, too, may change from day to day.

Not every posture requires a counterposture; we do not want to be continuously bending one way and then the other. Sometimes, we can perform a series of postures together—for example, a series of prone backward bends. It could be that only after the entire series do we need to take some counterposture. Another important principle here is that generally the counterposture is less intense than the main posture; it is not simply a movement in the opposite direction, but rather a gentler (usually dynamic) movement to address specific areas. Where there was compression, a counterposture can gently stretch; where there was holding, a counterposture can move; where there was asymmetry, a counterposture can realign.

Because the counterposture is less intense than the main posture, we also tend to perform it for fewer breaths. A good rule of thumb is that a counterposture should last somewhere between one third and one half of the length of the main posture(s). So, for example, 12 breaths in a lying twist (6 breaths to each side), would entail 4–6 breaths in counterposture. If we worked with a series of forward bends for 30 breaths, we would need 10–15 breaths in counterpostures—and there may be more than one counterposture here (to address different parts of the body).

Of all the possible movements of the spine, forward bends are the most useful when it comes to counterposture. Gary Kraftsow8 likens the forward bend to neutral when we change gears in a car—we have to travel through neutral to move from one gear to another. In the same way, when we move from twists to backward bends, or backward bends to flank stretches, symmetrical forward bends are required. The original shape of the spine in an embryo is flexion, so you could say that forward bends return the spine to its “default setting”—they “return us to ourselves.”

Forward bends require an exhalation, and exhalation is linked to letting go of the past. Often when we have just succeeded in doing something very difficult, or we want to move on from a situation, we breathe a sigh of relief; an exhalation helps us to move forward. Exhales have a psychologically soothing effect and help us “wipe the blackboard clean.” They clear what has accumulated and make a space to receive something new. Thus, in terms of both form and breath, forward bends are very useful as counterpostures.

We use a convenient acronym to remember the attributes of good counterposture—DOES:

Of course there may be exceptions to this, but these are useful guiding principles for us to consider when thinking about pratikriyāsana.