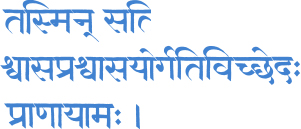

yoga sutra 2.49

tasmin-sati śvāsa-praśvāsayo -gati-viccheda

-gati-viccheda prā

prā āyāma

āyāma

Established in this (āsana), prā āyāma is regulating the flow of the inhalation and the exhalation

āyāma is regulating the flow of the inhalation and the exhalation

As with the sūtras on āsana, Patañjali takes the topic of prā āyāma and breaks it down into a definition (YS 2.49), a methodology (YS 2.50), and its fruit (YS 2.51, 2.52 and 2.53). However, there are at least three ways of understanding this sūtra in which Patañjali defines the basic parameters of prā

āyāma and breaks it down into a definition (YS 2.49), a methodology (YS 2.50), and its fruit (YS 2.51, 2.52 and 2.53). However, there are at least three ways of understanding this sūtra in which Patañjali defines the basic parameters of prā āyāma practice. The first words, tasmin and sati, mean that “something has been established.” Because this sūtra follows on immediately from those discussing āsana, it is clear that Patañjali is referring to a posture that has the qualities of sthira and sukha. To practice prā

āyāma practice. The first words, tasmin and sati, mean that “something has been established.” Because this sūtra follows on immediately from those discussing āsana, it is clear that Patañjali is referring to a posture that has the qualities of sthira and sukha. To practice prā āyāma properly, we need to feel comfortable in our seated posture so that we can remain undistracted. Prā

āyāma properly, we need to feel comfortable in our seated posture so that we can remain undistracted. Prā āyāma cannot be effective if we are concerned with the pain in our knee, or with a slouching spine and a collapsing chest. Nor can it arise if our minds are too distracted—there needs to be stability and freedom in both the body and the mind.

āyāma cannot be effective if we are concerned with the pain in our knee, or with a slouching spine and a collapsing chest. Nor can it arise if our minds are too distracted—there needs to be stability and freedom in both the body and the mind.

The next words, śvāsa and praśvāsa, can be understood in two different ways. At the most basic level, śvāsa simply means “breathing in” and praśvāsa means “breathing out.” However, the terms are only used on one other occasion in the whole text (YS 1.31), and this is in the context of Patañjali's description of the symptoms of experiencing obstacles. In YS 1.31, śvāsa and praśvāsa are not simply inhalation and exhalation, but the type of unconscious breathing which arises when we are experiencing suffering; in other words, Patañjali is describing an uneven, ragged and disturbed breath.

Finally, the last term, gativiccheda, is made up of two words. Viccheda means “cutting” or “stopping”; while gati implies a movement or a flow. When we combine this with the previous term (śvāsapraśvāsa, with its two meanings), a number of possible interpretations arise. First of all, if we understand the term śvāsapraśvāsa to refer not simply to the inhalation and the exhalation, but to a habituated, ragged, and disturbed breath (YS 1.31), then prā āyāma can be seen as stopping the flow (gativiccheda) of unconscious, poor breathing patterns (śvāsapraśvāsa) and instead cultivating a conscious and regulated way of breathing.

āyāma can be seen as stopping the flow (gativiccheda) of unconscious, poor breathing patterns (śvāsapraśvāsa) and instead cultivating a conscious and regulated way of breathing.

However, if we consider śvāsa and praśvāsa simply to mean “inhale” and “exhale,” we can also say that prā āyāma is “regulating the flow of the breath”—it is how we “cut” (gativiccheda) the different parts of the breath, how we divide the inhalation and the exhalation. This leads us to an understanding of prā

āyāma is “regulating the flow of the breath”—it is how we “cut” (gativiccheda) the different parts of the breath, how we divide the inhalation and the exhalation. This leads us to an understanding of prā āyāma as an exploration of breathing ratios—the length of time an inhalation takes compared to that of the exhalation. This is, of course, a fruitful area of study and practice, about which more later.

āyāma as an exploration of breathing ratios—the length of time an inhalation takes compared to that of the exhalation. This is, of course, a fruitful area of study and practice, about which more later.

Finally, we may consider gativiccheda to literally mean “stopping” or “arresting” the inhale and the exhale. This implies the cultivation of the pauses between inhaling and exhaling, or between exhaling and inhaling. Prā āyāma is thus the retention of the in-breath (called anta

āyāma is thus the retention of the in-breath (called anta kumbhaka, or “AK”) and the holding of the breath out (called bāhya kumbhaka, or “BK”). This is a quite different (although related) understanding of this sūtra's meaning.

kumbhaka, or “AK”) and the holding of the breath out (called bāhya kumbhaka, or “BK”). This is a quite different (although related) understanding of this sūtra's meaning.

Each of these three interpretations has value and can provide a useful springboard for us to examine the question of seated breathing practices, but it is the first understanding that is the most favored by Desikachar and his students.

āyāma

āyāmaWhat do we mean by prā āyāma? Practicing movements or āsana with synchronized breathing is not prā

āyāma? Practicing movements or āsana with synchronized breathing is not prā āyāma: prā

āyāma: prā āyāma is the conscious use of the breath in a static seated position. Desikachar described the relationship between body and breath in āsana and prā

āyāma is the conscious use of the breath in a static seated position. Desikachar described the relationship between body and breath in āsana and prā āyāma thus: “In āsana, we use the breath to support the body; in prā

āyāma thus: “In āsana, we use the breath to support the body; in prā āyāma, we use the body to support the breath”.1 In āsana our focus is on the body—the feelings that arise, the quality of the movement or the stretch, and the primary tool in refining the body's movements and stretching is the breath. Here, breath supports body. This is reversed in prā

āyāma, we use the body to support the breath”.1 In āsana our focus is on the body—the feelings that arise, the quality of the movement or the stretch, and the primary tool in refining the body's movements and stretching is the breath. Here, breath supports body. This is reversed in prā āyāma: now the body must simply remain still and comfortable, supporting the movements of the breath. This requires both stability and freedom in the vertical axis (the spine) and also in the horizontal axis (the hips, knees and ankles). Only then can the two great chambers of the torso, the chest and the abdomen, be free to move, expand and contract in a way that allows for the free passage of breath and thus the circulation of energy.

āyāma: now the body must simply remain still and comfortable, supporting the movements of the breath. This requires both stability and freedom in the vertical axis (the spine) and also in the horizontal axis (the hips, knees and ankles). Only then can the two great chambers of the torso, the chest and the abdomen, be free to move, expand and contract in a way that allows for the free passage of breath and thus the circulation of energy.

Prā āyāma is the final word of YS 2.49 and, as it is the key topic of this chapter, it's worth also exploring its component parts. It is made up of two words, prā

āyāma is the final word of YS 2.49 and, as it is the key topic of this chapter, it's worth also exploring its component parts. It is made up of two words, prā a and āyāma. We have already seen how prā

a and āyāma. We have already seen how prā a can be understood as energy (akin to the Chinese concept of chi or qi). Desikachar often described prā

a can be understood as energy (akin to the Chinese concept of chi or qi). Desikachar often described prā a as “a friend of puru

a as “a friend of puru a”: we can think of prā

a”: we can think of prā a as a sort of “go-between” linking puru

a as a sort of “go-between” linking puru a and prak

a and prak ti and allowing them to function together.

ti and allowing them to function together.

The second word, āyāma, is often translated as “extended” or “stretched”—and many translate this sūtra along the lines of “prā āyāma is the lengthening (āyāma) of the breath (prā

āyāma is the lengthening (āyāma) of the breath (prā a).” But the prefix ā here also reverses the direction with regard to the subject, thus āyāma means “to extend inwards”—to return, to come back. In the practice of prā

a).” But the prefix ā here also reverses the direction with regard to the subject, thus āyāma means “to extend inwards”—to return, to come back. In the practice of prā āyāma, we are concentrating our dissipated energy (prā

āyāma, we are concentrating our dissipated energy (prā a) by extending it inwards and making it flow powerfully and deeply within us, and thereby centering ourselves.

a) by extending it inwards and making it flow powerfully and deeply within us, and thereby centering ourselves.

āyāma

āyāmaFrom a traditional Ha ha Yoga perspective, prā

ha Yoga perspective, prā āyāma is the essential practice.2 While āsana is important, it is through the practice of prā

āyāma is the essential practice.2 While āsana is important, it is through the practice of prā āyāma that the yogi starts to manipulate the energies of the body and really turns inwards. It has its dangers, however. The Ha

āyāma that the yogi starts to manipulate the energies of the body and really turns inwards. It has its dangers, however. The Ha ha Yoga Pradīpikā has some serious warnings: “As the lion, elephant or tiger is tamed gradually, even so should prā

ha Yoga Pradīpikā has some serious warnings: “As the lion, elephant or tiger is tamed gradually, even so should prā a be brought under control, else it will kill the practitioner” (HYP 2.15). Perhaps it is for these reasons that prā

a be brought under control, else it will kill the practitioner” (HYP 2.15). Perhaps it is for these reasons that prā āyāma is rarely taught in group yoga classes, and also less commonly practiced. It can be viewed as an esoteric practice whereby one has to have mastered all the āsana before one is competent to practice prā

āyāma is rarely taught in group yoga classes, and also less commonly practiced. It can be viewed as an esoteric practice whereby one has to have mastered all the āsana before one is competent to practice prā āyāma.3 But what does it mean to have mastered all the postures? For us, the prerequisite for prā

āyāma.3 But what does it mean to have mastered all the postures? For us, the prerequisite for prā āyāma practice is simply an ability to remain in a comfortable seated posture with the qualities of both sthira and sukha.

āyāma practice is simply an ability to remain in a comfortable seated posture with the qualities of both sthira and sukha.

There are also other reasons why prā āyāma practice is often cursory, forgotten, or omitted. Prā

āyāma practice is often cursory, forgotten, or omitted. Prā āyāma is a subtler practice than āsana. A beginner can feel their hamstrings stretching, their hips opening or their back working. From the first class of āsana, a novice practitioner can notice a considerable difference in their mental outlook, a feeling of calm and focus. But prā

āyāma is a subtler practice than āsana. A beginner can feel their hamstrings stretching, their hips opening or their back working. From the first class of āsana, a novice practitioner can notice a considerable difference in their mental outlook, a feeling of calm and focus. But prā āyāma is more challenging, and many people wonder what exactly they are doing with their breath (and why)—especially when it involves fiddling with the nostrils and counting! Paul Harvey used to say that āsana works “from the outside in” and is therefore more immediately noticeable, while prā

āyāma is more challenging, and many people wonder what exactly they are doing with their breath (and why)—especially when it involves fiddling with the nostrils and counting! Paul Harvey used to say that āsana works “from the outside in” and is therefore more immediately noticeable, while prā āyāma works “from the inside out.”4 It takes time to feel its potency and its effects. Āsana also has many potential variations; there are endless ways that we can turn and move our bodies to make new shapes or sequences. In this sense, āsana can be fun, entertaining and engaging. But prā

āyāma works “from the inside out.”4 It takes time to feel its potency and its effects. Āsana also has many potential variations; there are endless ways that we can turn and move our bodies to make new shapes or sequences. In this sense, āsana can be fun, entertaining and engaging. But prā āyāma is a more “naked practice”; although there are many different possibilities of practice, the parameters are much reduced, and they all basically require us to remain seated and still, and focus on the subtle variations we can make in the techniques of breathing.

āyāma is a more “naked practice”; although there are many different possibilities of practice, the parameters are much reduced, and they all basically require us to remain seated and still, and focus on the subtle variations we can make in the techniques of breathing.

āyāma

āyāma

yoga sutra 2.50

bāhya-abhyantara-stambha-v tti deśa-kāla-sa

tti deśa-kāla-sa khyābhi

khyābhi parid

parid

o dīrgha-sūk

o dīrgha-sūk ma

ma

By observing the exhalation, the inhalation and the pauses between them from three perspectives (placing our attention, varying their relative lengths and considering the number of repetitions), we can refine both the length and subtlety of the whole breath5

Patañjali starts by identifying the three parts of the breath: bāhya (exhale), abhyantara (inhale) and stambha-v tti

tti (kumbhaka). There is an important order to this: the exhalation comes first and it is our primary concern because it is the foundation for the rest of the breath. As long as the exhalation is smooth, we can be assured that we are working within our limits. As Desikachar says:

(kumbhaka). There is an important order to this: the exhalation comes first and it is our primary concern because it is the foundation for the rest of the breath. As long as the exhalation is smooth, we can be assured that we are working within our limits. As Desikachar says:

Whichever technique we choose, the most important part of prā āyāma is the exhalation. If the quality of the exhalation is not good, the quality of the whole prā

āyāma is the exhalation. If the quality of the exhalation is not good, the quality of the whole prā āyāma practice is adversely affected. When someone is not able to breathe out slowly and quietly it means that he or she is not ready for prā

āyāma practice is adversely affected. When someone is not able to breathe out slowly and quietly it means that he or she is not ready for prā āyāma, either mentally or otherwise. Indeed, some texts give this warning: if the inhalation is rough we do not have to worry, but if the exhalation is uneven it is a sign of illness, either present or impending.6

āyāma, either mentally or otherwise. Indeed, some texts give this warning: if the inhalation is rough we do not have to worry, but if the exhalation is uneven it is a sign of illness, either present or impending.6

Having identified the three different parts of the breath (the exhalation, bāhya; the inhalation, abhyantara; and the pauses between, stambha v tti), Patañjali gives us three “viewing towers,” from which we can gain a perspective on, and also some control over, our breath. These three are the essential variables of the breath and they define what we can do within prā

tti), Patañjali gives us three “viewing towers,” from which we can gain a perspective on, and also some control over, our breath. These three are the essential variables of the breath and they define what we can do within prā āyāma practice:

āyāma practice:

deśa—means “place” and so this refers to where we focus our attention. Generally, this is seen as the primary site of breath control, the place where we create a valve to lengthen and refine the quality of the breath. Thus, in nostril control breathing, it would be in the nostril through which we are inhaling or exhaling; in ujjāyī, it is the throat; and in śītalī or sītkārī, it is the tongue. However, deśa can also refer to other places in the body where we might place our focus, for example, the chest as we inhale and the abdomen as we exhale.

kāla—means “time.” Here Patañjali is referring to the duration of the breath. This implies investigating how to make the breath long and the effects of its different components. An important technique for this is to formally explore the relative timings of the different parts of the breath—in other words, ratio. Although we never make the inhalation longer than the exhalation (this would be too stimulating), by making them equal, there is a mild b

ha

ha a quality which can be enhanced by adding a hold (AK) after the inhalation. Similarly, the longer we make the exhalation in relationship to the inhalation, the more we make the breath la

a quality which can be enhanced by adding a hold (AK) after the inhalation. Similarly, the longer we make the exhalation in relationship to the inhalation, the more we make the breath la ghana. This can also be enhanced by the addition of a pause (BK) after the exhalation.

ghana. This can also be enhanced by the addition of a pause (BK) after the exhalation.

sa khyā—the last parameter is that of numbers. Sam links to the English word “sum” and khyā, in this context, is “count.” Sa

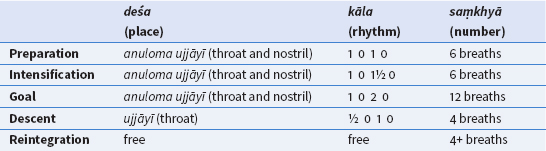

khyā—the last parameter is that of numbers. Sam links to the English word “sum” and khyā, in this context, is “count.” Sa khyā thus refers to the total number of breaths we take. We may take six breaths with one ratio (as preparation), a further twelve breaths with a more intense ratio (as the main body of the practice) and finally six breaths of a lighter ratio as a “cool down.” Therefore, sa

khyā thus refers to the total number of breaths we take. We may take six breaths with one ratio (as preparation), a further twelve breaths with a more intense ratio (as the main body of the practice) and finally six breaths of a lighter ratio as a “cool down.” Therefore, sa khyā implies both the overall length of the practice, which in some measure at least determines its intensity, and its structure in terms of the vinyāsa krama, the number of breaths at each stage and their progression.

khyā implies both the overall length of the practice, which in some measure at least determines its intensity, and its structure in terms of the vinyāsa krama, the number of breaths at each stage and their progression.

Patañjali uses the term parid

a (“to view from all around”) to refer to how we observe these three conditions. These are the watchtowers—three different perspectives on the breath from which we can lengthen and refine. This is a very important principle that Swami Hariharānanda7 reminds us about in relation to sa

a (“to view from all around”) to refer to how we observe these three conditions. These are the watchtowers—three different perspectives on the breath from which we can lengthen and refine. This is a very important principle that Swami Hariharānanda7 reminds us about in relation to sa yama (meditative enquiry). He emphasizes that to really understand something we must investigate it from different perspectives so that our comprehension is complete and “well rounded.” Thus, parid

yama (meditative enquiry). He emphasizes that to really understand something we must investigate it from different perspectives so that our comprehension is complete and “well rounded.” Thus, parid

a is a general and important principle in practice: to approach and investigate from all sides, with different supports and perspectives. Only when these three parameters have been sensitively observed and refined do we move towards a breath with the ideal twin qualities of dīrgha (long) and sūk

a is a general and important principle in practice: to approach and investigate from all sides, with different supports and perspectives. Only when these three parameters have been sensitively observed and refined do we move towards a breath with the ideal twin qualities of dīrgha (long) and sūk ma (subtle).

ma (subtle).

At an initial level, dīrgha can simply imply a lengthening of the breath, and sūk ma a refining of it, such that it becomes quiet, smooth and even. This is certainly an essential prerequisite, but as we develop our practice more deeply, we might reflect on more nuanced meanings. Simply lengthening the breath may be limited—like a stretched-out piece of chewing gum, as Peter Hersnack often used to say. Dīrgha is not necessarily simply “more of the same”; instead, it is (to use Peter's words again) “where the breath opens up on itself to create timeless holes or pockets of infinity.”8 The very quality of the breath becomes more spacious. In the same way, we can think of sūk

ma a refining of it, such that it becomes quiet, smooth and even. This is certainly an essential prerequisite, but as we develop our practice more deeply, we might reflect on more nuanced meanings. Simply lengthening the breath may be limited—like a stretched-out piece of chewing gum, as Peter Hersnack often used to say. Dīrgha is not necessarily simply “more of the same”; instead, it is (to use Peter's words again) “where the breath opens up on itself to create timeless holes or pockets of infinity.”8 The very quality of the breath becomes more spacious. In the same way, we can think of sūk ma not just as making the breath quieter—a change in volume—but rather a “change in the frequency,” in the actual quality as well.

ma not just as making the breath quieter—a change in volume—but rather a “change in the frequency,” in the actual quality as well.

Dīrgha and sūk ma are the fruit of deśa, kāla and sa

ma are the fruit of deśa, kāla and sa khyā. Because they are essential qualities of the breath in this practice, they are to prā

khyā. Because they are essential qualities of the breath in this practice, they are to prā āyāma what sthira and sukha are to āsana.

āyāma what sthira and sukha are to āsana.

āyāma

āyāma

yoga sutra 2.51

bāhya-abhyantara-vi aya-āk

aya-āk epī caturtha

epī caturtha

In the fourth state (of breathing), the normal processes of “inhalation” and “exhalation” are transcended

This is a mysterious sūtra. Wendy Doniger9 discusses how there are many groups of three in the Indian philosophical tradition, and they are joined—and then transcended—by a mysterious fourth principle. The first three are worldly; the fourth is of another dimension. Thus, for example, in the four aims of life (puru ārtha), the first three—duty, the pursuit of wealth and sensual fulfilment (dharma, artha and kāma respectively)—belong to the world and apply to everyone all the time. The fourth one, liberation (mok

ārtha), the first three—duty, the pursuit of wealth and sensual fulfilment (dharma, artha and kāma respectively)—belong to the world and apply to everyone all the time. The fourth one, liberation (mok a), is of a different order and will only be pursued by a limited number of people. Similarly, there are three stages to life (āśrama) for all normal people: student, householder and retired (brahmacarya, g

a), is of a different order and will only be pursued by a limited number of people. Similarly, there are three stages to life (āśrama) for all normal people: student, householder and retired (brahmacarya, g hastha and vanaprastha respectively). But a fourth category, sa

hastha and vanaprastha respectively). But a fourth category, sa nyāsa, suggests the possibility of a complete renunciation. There are even three strands which create the fabric of prak

nyāsa, suggests the possibility of a complete renunciation. There are even three strands which create the fabric of prak ti—tamas, rajas and sattva. Thus, prak

ti—tamas, rajas and sattva. Thus, prak ti is called sagu

ti is called sagu a—with qualities. But beyond these is puru

a—with qualities. But beyond these is puru a, which is without qualities and therefore nirgu

a, which is without qualities and therefore nirgu a.

a.

In this sūtra on prā āyāma, we are introduced to a mysterious fourth type of breath which is of a different order from anything to do with conscious inhalation, exhalation or the stopping of the breath. Desikachar rather cryptically comments, “An entirely different state of breathing appears in the state of yoga. . . . It is not possible to be more specific.”10 It is easy to view this sūtra as something of an oddball—and so esoteric that it really has little relevance to us mere mortals. But if we view it as something reachable, real and fundamental to prā

āyāma, we are introduced to a mysterious fourth type of breath which is of a different order from anything to do with conscious inhalation, exhalation or the stopping of the breath. Desikachar rather cryptically comments, “An entirely different state of breathing appears in the state of yoga. . . . It is not possible to be more specific.”10 It is easy to view this sūtra as something of an oddball—and so esoteric that it really has little relevance to us mere mortals. But if we view it as something reachable, real and fundamental to prā āyāma then it can have more relevance. We can see it as a type of breathing where volition and intention have been transcended, and the breath has become so subtle that concepts of “inside” and “outside” seem no longer to apply. The difference between inhalation, exhalation and pauses is barely perceptible: the breath (and by implication, the thoughts) becomes like “ripples on the surface of Being.”11 This new quality of the breath (and the mind), where there is hardly any movement, opens up a spaciousness within the breath itself. This space is a space for perception, for presence and for freedom. We can view all the techniques of prā

āyāma then it can have more relevance. We can see it as a type of breathing where volition and intention have been transcended, and the breath has become so subtle that concepts of “inside” and “outside” seem no longer to apply. The difference between inhalation, exhalation and pauses is barely perceptible: the breath (and by implication, the thoughts) becomes like “ripples on the surface of Being.”11 This new quality of the breath (and the mind), where there is hardly any movement, opens up a spaciousness within the breath itself. This space is a space for perception, for presence and for freedom. We can view all the techniques of prā āyāma (which are described in more detail below) as steps to move us towards this fourth type of breathing; they are platforms that we build and work with in order to leap off and fly freely. This fourth type of breathing is a sign that something has opened to the very source of the breath.

āyāma (which are described in more detail below) as steps to move us towards this fourth type of breathing; they are platforms that we build and work with in order to leap off and fly freely. This fourth type of breathing is a sign that something has opened to the very source of the breath.

yoga sutra 2.52

tata k

k iyate prakāśa-āvara

iyate prakāśa-āvara am

am

From this, blockages are destroyed and our inner light is revealed

Although it is not usual, we can consider this clear statement to be referring directly to YS 2.51, the previous sūtra (as opposed to YS 2.50). Thus: a state of clarity arises when our breath has become so subtle that a new quality of spaciousness has opened it up from inside. This state of clarity marks the fruition of a new type of breathing. The word āvara a (covering) is a synonym for tamas;12 and it is this tamas which is said to obscure our vision and perception. Prā

a (covering) is a synonym for tamas;12 and it is this tamas which is said to obscure our vision and perception. Prā āyāma dissolves (k

āyāma dissolves (k iyate) that which obscures (tamas). As the tamas is reduced, so our natural clarity is enhanced. Here Patañjali uses the word prakāśa, which, as we have seen, refers to sattva gu

iyate) that which obscures (tamas). As the tamas is reduced, so our natural clarity is enhanced. Here Patañjali uses the word prakāśa, which, as we have seen, refers to sattva gu a. So, we have a direct statement about how the correct practice of prā

a. So, we have a direct statement about how the correct practice of prā āyāma reduces tamas and enhances both sattva and perception. Certainly, we are often more sensitive, clearer, and our eyes appear to sparkle after prolonged and dedicated prā

āyāma reduces tamas and enhances both sattva and perception. Certainly, we are often more sensitive, clearer, and our eyes appear to sparkle after prolonged and dedicated prā āyāma practice.

āyāma practice.

yoga sutra 2.53

dhāra āsu ca yogyatā manasa

āsu ca yogyatā manasa

And the mind is made fit for dhāra ā

ā

Dhāra ā is the doorway into meditation, and it requires us to stay with one thought, or object, for a length of time. In other words, dhāra

ā is the doorway into meditation, and it requires us to stay with one thought, or object, for a length of time. In other words, dhāra ā requires a certain stability of mind: we can't focus on a single principle if we are distracted. In this final fruit of prā

ā requires a certain stability of mind: we can't focus on a single principle if we are distracted. In this final fruit of prā āyāma, Patañjali gives us another compelling reason to practice: it reduces movement (rajas) and thus agitation in the mind and senses.13 Anyone who has developed their prā

āyāma, Patañjali gives us another compelling reason to practice: it reduces movement (rajas) and thus agitation in the mind and senses.13 Anyone who has developed their prā āyāma practice will know that the ability to sit still for meditative practices is hugely enhanced by some seated breathing; it is as if prā

āyāma practice will know that the ability to sit still for meditative practices is hugely enhanced by some seated breathing; it is as if prā āyāma has prepared the ground and now dhāra

āyāma has prepared the ground and now dhāra ā can begin to arise with much less effort. Interestingly, Patañjali uses the suffix su at the end of dhāra

ā can begin to arise with much less effort. Interestingly, Patañjali uses the suffix su at the end of dhāra ā. Su implies a plural—many forms of dhāra

ā. Su implies a plural—many forms of dhāra ā can arise. In Chapter 3 of the Yoga Sūtra (Vibhūti Pāda), Patañjali describes the possibilities of directing the mind towards many different objects and explores the various sorts of powers (siddhi) which arise from such practices.

ā can arise. In Chapter 3 of the Yoga Sūtra (Vibhūti Pāda), Patañjali describes the possibilities of directing the mind towards many different objects and explores the various sorts of powers (siddhi) which arise from such practices.

Sādhana: Techniques of prā āyāma

āyāma

As with āsana, Patañjali has very little to say in the Yoga Sūtra about the actual mechanics of practicing prā āyāma. Later Ha

āyāma. Later Ha ha Yoga texts have much more information on the different techniques—their application, their value and their potential dangers. The Ha

ha Yoga texts have much more information on the different techniques—their application, their value and their potential dangers. The Ha ha Yoga Pradīpikā presents nā

ha Yoga Pradīpikā presents nā ī śodhana as the definitive prā

ī śodhana as the definitive prā āyāma technique.14 It lists a further eight techniques which are collectively called kumbhaka.15 These are sūrya bhedana, ujjāyī, sītkārī, śītalī, bhastrikā, bhrāmarī, mūrcchā and plāvinī. Another common technique practiced in yoga classes is kapālabhāti, but this is described as a kriyā16 (cleansing action) in the HYP. While we regularly use ujjāyī, sītkārī, śītalī and sometimes sūrya bhedana, bhastrikā and bhrāmarī, it is unusual to practice mūrcchā and plāvinī. Krishnamacharya, and then subsequently his students, added some additional techniques to this list: anuloma ujjāyī, viloma ujjāyī and pratiloma ujjāyī. These additions are basically modifications of nā

āyāma technique.14 It lists a further eight techniques which are collectively called kumbhaka.15 These are sūrya bhedana, ujjāyī, sītkārī, śītalī, bhastrikā, bhrāmarī, mūrcchā and plāvinī. Another common technique practiced in yoga classes is kapālabhāti, but this is described as a kriyā16 (cleansing action) in the HYP. While we regularly use ujjāyī, sītkārī, śītalī and sometimes sūrya bhedana, bhastrikā and bhrāmarī, it is unusual to practice mūrcchā and plāvinī. Krishnamacharya, and then subsequently his students, added some additional techniques to this list: anuloma ujjāyī, viloma ujjāyī and pratiloma ujjāyī. These additions are basically modifications of nā ī śodhana using ujjāyī to punctuate the rhythm of the nostril control. Each has a role in helping us to access nā

ī śodhana using ujjāyī to punctuate the rhythm of the nostril control. Each has a role in helping us to access nā ī śodhana; however, to view them as only training techniques is to undervalue their unique flavors. Particularly when combined with creative bhāvana, they can each lead to unique experiences and contribute to the parid

ī śodhana; however, to view them as only training techniques is to undervalue their unique flavors. Particularly when combined with creative bhāvana, they can each lead to unique experiences and contribute to the parid

a of the breath, or support therapeutic goals.

a of the breath, or support therapeutic goals.

The “placing of the attention” is a way that we can understand two aspects of prā āyāma: bhāvana and also the actual technique. The use of bhāvana can be particularly powerful when working with prā

āyāma: bhāvana and also the actual technique. The use of bhāvana can be particularly powerful when working with prā āyāma; it transforms a simple breathing practice into one which profoundly engages the mind. Each inhalation can invite a sense of opening from the inside, while each exhalation can invite a feeling of the breath withdrawing. We can also visualize something of the difference between left and right—the left linking to the lunar channel and qualities of coolness and the feminine, while the right side links to the solar channel, heat and the masculine. By “placing our attention” in this way, we deepen our involvement and put something of ourselves into the practice.

āyāma; it transforms a simple breathing practice into one which profoundly engages the mind. Each inhalation can invite a sense of opening from the inside, while each exhalation can invite a feeling of the breath withdrawing. We can also visualize something of the difference between left and right—the left linking to the lunar channel and qualities of coolness and the feminine, while the right side links to the solar channel, heat and the masculine. By “placing our attention” in this way, we deepen our involvement and put something of ourselves into the practice.

The second aspect, the “placing of the attention with regard to technique,” also transforms a simple practice. Just as we can divide āsana into various groups depending on the action of the spine,17 so can we divide prā āyāma techniques into groups according to their primary place of regulation—nostril control, throat control or mouth control.

āyāma techniques into groups according to their primary place of regulation—nostril control, throat control or mouth control.

We have already discussed ujjāyī in Chapter 9, but there is a subtle difference between how we use ujjāyī in āsana and in prā āyāma. In the former, it is usually a little louder (generally speaking, the more demanding the physical work, the louder the breath). In the latter, ujjāyī can be refined so that it is much more of a “caress” of the throat—a gentle feeling, like silk on marble, and barely audible at all. Ujjāyī is a technique intimately linked to the body—it “gives body to the breath.” However, we can over-control it and it becomes labored and regimented. As we inhale, we may experience a profound opening from within. If, as we exhale, we can maintain this feeling, there is a feeling of the body remaining open as the breath “withdraws” back to its source at our center.

āyāma. In the former, it is usually a little louder (generally speaking, the more demanding the physical work, the louder the breath). In the latter, ujjāyī can be refined so that it is much more of a “caress” of the throat—a gentle feeling, like silk on marble, and barely audible at all. Ujjāyī is a technique intimately linked to the body—it “gives body to the breath.” However, we can over-control it and it becomes labored and regimented. As we inhale, we may experience a profound opening from within. If, as we exhale, we can maintain this feeling, there is a feeling of the body remaining open as the breath “withdraws” back to its source at our center.

The breath, the spine, the chest and the abdomen are all brought in to play. When they are working harmoniously, the quality of ujjāyī becomes an expression of what is happening in the body, rather than as something manipulated, manufactured and controlled. Ujjāyī is thus a “whole body” practice, not just something which happens in the throat. Nevertheless, it is still necessary to apply the restriction in the throat to create the friction required for ujjāyī.

Implicit in the technique of ujjāyī is a vertical polarity—that of head and pelvis, of chest and abdomen, and prā a and apāna. But it's also worth remembering that ujjāyī is fundamentally a symmetrical technique; it does not address the relationship between the two sides of the body. It is only when we introduce nostril control breathing that the breath becomes asymmetrical. While ujjāyī is unifying, we could say the introduction of nostril control breathing is separating. It allows us to view one side from the other side, to make distinctions—and thereby to forge new relationships between left and right. The hand position that enables nostril control breathing is m

a and apāna. But it's also worth remembering that ujjāyī is fundamentally a symmetrical technique; it does not address the relationship between the two sides of the body. It is only when we introduce nostril control breathing that the breath becomes asymmetrical. While ujjāyī is unifying, we could say the introduction of nostril control breathing is separating. It allows us to view one side from the other side, to make distinctions—and thereby to forge new relationships between left and right. The hand position that enables nostril control breathing is m gi mudrā (fig 10.1).

gi mudrā (fig 10.1).

M gi mudrā allows us to create a very fine valve in the nostril to regulate the breath. Whether one is inhaling or exhaling, during alternate nostril breathing, one nostril is completely closed and the other is partially restricted.18 The amount of pressure that we apply to the nostril through which we breathe will vary: if our nostril is completely clear, we may nearly completely close the nostril; if our nostril is less clear, it may be necessary to hardly close it at all. It is very important that no trace of ujjāyī remains as we breathe through one nostril—the throat should be completely relaxed and any noise or friction is experienced only in the nostril. The nostril, therefore, is the deśa.

gi mudrā allows us to create a very fine valve in the nostril to regulate the breath. Whether one is inhaling or exhaling, during alternate nostril breathing, one nostril is completely closed and the other is partially restricted.18 The amount of pressure that we apply to the nostril through which we breathe will vary: if our nostril is completely clear, we may nearly completely close the nostril; if our nostril is less clear, it may be necessary to hardly close it at all. It is very important that no trace of ujjāyī remains as we breathe through one nostril—the throat should be completely relaxed and any noise or friction is experienced only in the nostril. The nostril, therefore, is the deśa.

Ujjāyī is a great technique for use in āsana, but undoubtedly it is less subtle than nostril control breathing. By closing one nostril completely, and then partially closing the other, we are in effect significantly reducing the area through which we breathe with the aim of refining the breath. Because of this significant reduction, if there is any blockage, people can easily feel claustrophobic with these techniques. Refining the breath is important, but another key difference between ujjāyī and nostril control is that ujjāyī is more linked to the body, whereas nostril control is more linked to the mind. The experience of the breath is more downwards (and into the body) with ujjāyī, and more upwards (and into the head) with nostril control techniques.

By introducing nostril breathing at various points in the breathing cycle, the following three variations of ujjāyī allow us to move towards nā ī śodhana.19

ī śodhana.19

The first nostril control technique that we introduce is anuloma ujjāyī—literally “with the grain of the hair” (anu means “with,” loman is hair). Because the hairs in the nostrils point towards the opening, they act as a filter to inhaled air. Going with the grain, therefore, is moving outwards and it is linked to the exhalation. Anuloma ujjāyī uses ujjāyī (the throat) to modulate and support the breath on the inhalation, but transfers that support to one nostril as we exhale. The deśa thus shifts: throat as we inhale, one nostril as we exhale.

Anuloma ujjāyī is a tool for refining and lengthening the exhalation, and it helps to clear the nostrils. Because it favors lengthening the exhalation it is often thought of as a la ghana technique, and a relaxing prā

ghana technique, and a relaxing prā āyāma.

āyāma.

Because ujjāyī links more to the body, and nostril control more to mind, we can also understand anuloma ujjāyī as applying ujjāyī on the inhalation (body focus), and nostril control on the exhalation (mental focus). Thus anuloma ujjāyī “allows the mind (nostril control on exhale) to take support on the body (ujjāyī on inhale).”20 In this way, the practice of anuloma ujjāyī reveals something about our current bodily state; the body comes into presence. Students sometimes say that anuloma ujjāyī leaves them feeling tired and that it is too la ghana. But if we understand the technique as becoming present to the state of the body, then actually they are simply realizing how tired they are; their bodily state is revealed. The body is brought into presence.

ghana. But if we understand the technique as becoming present to the state of the body, then actually they are simply realizing how tired they are; their bodily state is revealed. The body is brought into presence.

Viloma ujjāyī is the opposite of anuloma ujjāyī.21 Vi used here as a prefix means “against”—so this technique is “against the grain of the hair.” In viloma ujjāyī, we inhale through a single nostril and exhale through both using ujjāyī. The deśa moves from the nostril (on the inhalation) to the throat (on the exhalation). Because the nostril is a conical shape, with the widest part at the entrance, when we inhale we are breathing into a narrowing space. By only inhaling into one nostril and then by adding a further restriction using m gi mudrā, this technique can feel quite suffocating to the novice. However, to a more experienced practitioner, the friction caused by the m

gi mudrā, this technique can feel quite suffocating to the novice. However, to a more experienced practitioner, the friction caused by the m gi mudrā on the inhalation can really support the refinement and lengthening of the inhalation. Moreover, viloma ujjāyī allows “the mind (nostril control on inhale) to become a support for the body (ujjāyī on exhale).”22 Thus, it helps us to actualize and to embody—by translating ideas and thoughts into bodily possibilities. In other words, it helps us to get things done.

gi mudrā on the inhalation can really support the refinement and lengthening of the inhalation. Moreover, viloma ujjāyī allows “the mind (nostril control on inhale) to become a support for the body (ujjāyī on exhale).”22 Thus, it helps us to actualize and to embody—by translating ideas and thoughts into bodily possibilities. In other words, it helps us to get things done.

The final technique lies somewhere between ujjāyī and nā ī śodhana, and is a combination of the anuloma and viloma ujjāyī described above. We breathe in using ujjāyī, we exhale through the left nostril (anuloma ujjāyī), and then we breathe in though the left and exhale using ujjāyī (viloma ujjāyī). This pattern is then repeated on the right side. In pratiloma ujjāyī, the deśa shifts after every inhale. We move from the throat to one nostril, back to the throat and then to the other nostril. The technique neither favors the inhalation nor the exhalation; it is “the Great Equalizer.” It requires us to remain present and focused; the continuous change of deśa demands our involvement. Peter Hersnack said of this technique that it “gives us a stable presence in the world.”23 Pratiloma ujjāyī is certainly a very engaging technique; it has something of everything and the throat breathing provides a sort of “release valve” for any tension accrued during nostril control. This is excellent preparation for meditative practices and also for developing inhalations, exhalations and kumbhaka evenly.

ī śodhana, and is a combination of the anuloma and viloma ujjāyī described above. We breathe in using ujjāyī, we exhale through the left nostril (anuloma ujjāyī), and then we breathe in though the left and exhale using ujjāyī (viloma ujjāyī). This pattern is then repeated on the right side. In pratiloma ujjāyī, the deśa shifts after every inhale. We move from the throat to one nostril, back to the throat and then to the other nostril. The technique neither favors the inhalation nor the exhalation; it is “the Great Equalizer.” It requires us to remain present and focused; the continuous change of deśa demands our involvement. Peter Hersnack said of this technique that it “gives us a stable presence in the world.”23 Pratiloma ujjāyī is certainly a very engaging technique; it has something of everything and the throat breathing provides a sort of “release valve” for any tension accrued during nostril control. This is excellent preparation for meditative practices and also for developing inhalations, exhalations and kumbhaka evenly.

ī śodhana: Giving us an active presence in the world

ī śodhana: Giving us an active presence in the worldThe prā āyāma technique par excellence is nā

āyāma technique par excellence is nā ī śodhana. Nā

ī śodhana. Nā ī means “channel” or “river,” while śodhana is a means of cleansing (śauca); so nā

ī means “channel” or “river,” while śodhana is a means of cleansing (śauca); so nā ī śodhana is the technique that purifies the channels through which our prā

ī śodhana is the technique that purifies the channels through which our prā a runs. This is nostril control with no compromise: we inhale through the left nostril and then exhale through the right; this is then reversed so we inhale through the right and exhale through the left. There is no trace of ujjāyī; the friction of the breath is felt entirely in the nostrils and so the deśa simply moves from one nostril to the other.

a runs. This is nostril control with no compromise: we inhale through the left nostril and then exhale through the right; this is then reversed so we inhale through the right and exhale through the left. There is no trace of ujjāyī; the friction of the breath is felt entirely in the nostrils and so the deśa simply moves from one nostril to the other.

In Ha ha Yoga's esoteric conception of the energetic body, the two nostrils symbolize an important polarity. The left nostril (i

ha Yoga's esoteric conception of the energetic body, the two nostrils symbolize an important polarity. The left nostril (i ā) is associated with the feminine, the moon and with cooling, while the right nostril (pi

ā) is associated with the feminine, the moon and with cooling, while the right nostril (pi galā) is associated with the masculine, the sun and heating. When we breathe through the left nostril, our prā

galā) is associated with the masculine, the sun and heating. When we breathe through the left nostril, our prā a is said to flow in i

a is said to flow in i ā nā

ā nā ī; likewise breathing though the right nostril means it flows in pi

ī; likewise breathing though the right nostril means it flows in pi galā nā

galā nā ī. These two great channels weave their way down the vertical axis, intersecting at highly charged points known as cakra (fig 10.2).

ī. These two great channels weave their way down the vertical axis, intersecting at highly charged points known as cakra (fig 10.2).

It is said that as long as we remain caught in the duality of male/female or sun/moon, then we remain, at some level, divided from the world and ourselves. We are cut off, and we experience isolation. The project of Ha ha Yoga is to bring these two aspects into a harmonious relationship that facilitates an experience of true presence, of Being There, undivided. Symbolically, this is described as the breath flowing in the (usually blocked) central channel—the su

ha Yoga is to bring these two aspects into a harmonious relationship that facilitates an experience of true presence, of Being There, undivided. Symbolically, this is described as the breath flowing in the (usually blocked) central channel—the su um

um ā—and nā

ā—and nā ī śodhana is the practice to facilitate this.

ī śodhana is the practice to facilitate this.

An effective bhāvana which Peter Hersnack sometimes taught involved a gentle lifting on one side of the abdomen as we exhale through one nostril (on the same side as the lift), and a “placing down” on the same side as we inhale. He called this “an inner walk.” This “inner walk” is also a sort of “inner dialogue” between our two sides and it creates both stability and openness. Nā ī śodhana thus gives us, in Peter's words, “an active presence in the world.”24

ī śodhana thus gives us, in Peter's words, “an active presence in the world.”24

In the following two prā āyāma techniques, the deśa is placed in the mouth—and specifically the tongue—as we inhale.

āyāma techniques, the deśa is placed in the mouth—and specifically the tongue—as we inhale.

This technique requires us to curl the tongue into a tube and stick it out as we breathe in, “drinking” the air in, as if through a straw. At the same time, we lift the chin as if drinking from a glass, making the inhalation as quiet and smooth as possible. At the end of the inhalation, we then retract the tongue and close the mouth, lift the tongue to the palate, and lower the chin back down to stabilize the head before finally exhaling slowly using ujjāyī. Implicit in the technique, therefore, is a short pause after the inhalation. Because the inhaled air travels through the tube of the tongue, it picks up moisture and the breath feels refreshing and cool as it enters the system, which is why śītalī is known as “the cooling breath.” It is very important to reconnect the tongue to the roof of the mouth after inhalation because this stimulates salivation and keeps the tongue moist; if we don't, then after a few breaths the tongue begins to feel like a dried-out piece of leather in the mouth. As an interesting variation to engage us, refine the exhalation and prepare for further techniques involving the nostrils, śītalī can also be combined with alternative nostril breathing exhalation.

It is best used sparingly—probably no more than about twelve breaths at a time. However, it can be an excellent therapeutic tool; it soothes any tendency towards nausea, heartburn or indigestion, as well as calming the mind. It is a very useful to combine śītalī with other techniques (for example, anuloma ujjāyī or nā ī śodhana) in a longer prā

ī śodhana) in a longer prā āyāma practice.

āyāma practice.

Finally, it is also a technique that can effectively be used in āsana—for example in mahā mudrā, in the cat (cakravākāsana) and even in the headstand (śir āsana)—although obviously here there would be no movement of the head.

āsana)—although obviously here there would be no movement of the head.

Of course, not everyone can actually roll their tongue in such a way that makes śītalī possible and in such cases, we use sītkārī. Although the Ha ha Yoga Pradīpikā describes it as a completely different technique, we use sītkārī as a modification for those who are unable to practice śītalī.

ha Yoga Pradīpikā describes it as a completely different technique, we use sītkārī as a modification for those who are unable to practice śītalī.

Rather charmingly, the Ha ha Yoga Pradīpikā claims that the diligent practitioner of sītkārī will become “a second God of Love” (HYP 2.54). As with śītalī the breath is inhaled through the mouth, the difference being that instead of drawing the breath through the curled tongue, here the tongue is pressed against the lower teeth (with the tip pointing downwards) and the breath drawn over the tongue. This creates a slight hissing sound (sītkārī literally means “creating a ‘ssss’ sound”). The tongue also needs to be re-moisturized using sītkārī for the same reasons as śītalī. In fact, most of what can be said of śītalī can also apply to sītkārī.

ha Yoga Pradīpikā claims that the diligent practitioner of sītkārī will become “a second God of Love” (HYP 2.54). As with śītalī the breath is inhaled through the mouth, the difference being that instead of drawing the breath through the curled tongue, here the tongue is pressed against the lower teeth (with the tip pointing downwards) and the breath drawn over the tongue. This creates a slight hissing sound (sītkārī literally means “creating a ‘ssss’ sound”). The tongue also needs to be re-moisturized using sītkārī for the same reasons as śītalī. In fact, most of what can be said of śītalī can also apply to sītkārī.

Although we have not addressed some of the prā āyāmas referred to in the Ha

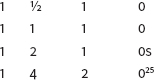

āyāmas referred to in the Ha ha Yoga Pradīpikā, the above comprise the most common techniques we practice. We can see how we have three major deśa for the attention (throat, nostrils and mouth) in five possible combinations:

ha Yoga Pradīpikā, the above comprise the most common techniques we practice. We can see how we have three major deśa for the attention (throat, nostrils and mouth) in five possible combinations:

ī śodhana

ī śodhanaThe second means to gain perspective on the breath is by regulating its rhythm. By dividing the breath into four parts and then consciously adjusting their various lengths in relationship to one another, we can alter both the feeling and the effect of the prā āyāma technique considerably. We can make the breath more stimulating by giving more proportional length to the inhalation and anta

āyāma technique considerably. We can make the breath more stimulating by giving more proportional length to the inhalation and anta kumbhaka (AK), or we could make the breath more relaxing by emphasizing the exhalation and bāhya kumbhaka (BK).

kumbhaka (AK), or we could make the breath more relaxing by emphasizing the exhalation and bāhya kumbhaka (BK).

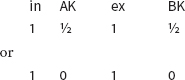

Traditionally, the rhythms were broadly divided into two categories: samav tti and vi

tti and vi amav

amav tti. In samav

tti. In samav tti, the separate parts of the breath are equal in length:

tti, the separate parts of the breath are equal in length:

If we make each unit 4 seconds, we would have one breath cycle lasting 16 seconds. This is very different from making each unit 12 seconds and having a 48-second complete breath. Both are samav tti, but the longer breath is obviously far more intense and demanding. Thus, the length (of the complete breath) as well as the rhythm are significant factors in defining intensity.

tti, but the longer breath is obviously far more intense and demanding. Thus, the length (of the complete breath) as well as the rhythm are significant factors in defining intensity.

Strictly speaking, all other rhythms are vi amav

amav tti, that is, having unequal parts. However, by dropping the lengths of the AK and the BK equally (or indeed, excluding them altogether), we can experience a “modified” samav

tti, that is, having unequal parts. However, by dropping the lengths of the AK and the BK equally (or indeed, excluding them altogether), we can experience a “modified” samav tti, a sort of “samav

tti, a sort of “samav tti light”:

tti light”:

Both of these are very effective rhythms to produce a feeling of containment and stability. In fact, because these are less intense than a full 1.1.1.1 rhythm, they have a more balanced feel to them; 1.1.1.1 can be very demanding!

There is a huge variety of potential vi amav

amav tti rhythms, and their spectrum can be from the very mild and therapeutic to the extremely intense. We should adhere to a few general principles for safety's sake (these apply to samav

tti rhythms, and their spectrum can be from the very mild and therapeutic to the extremely intense. We should adhere to a few general principles for safety's sake (these apply to samav tti rhythms too):

tti rhythms too):

What are we looking for when practicing vi amav

amav tti prā

tti prā āyāma? Do we want a more la

āyāma? Do we want a more la ghana or more b

ghana or more b

ha

ha a effect? The specific technique, the length of the breath and its rhythm will all have a bearing on this. A longer complete breath length will tend to exaggerate the rhythm's intrinsic effect.

a effect? The specific technique, the length of the breath and its rhythm will all have a bearing on this. A longer complete breath length will tend to exaggerate the rhythm's intrinsic effect.

Any rhythm that favors the inhalation and AK over the exhalation and BK is b

ha

ha a. Common b

a. Common b

ha

ha a rhythms might include:

a rhythms might include:

If we want to make the breath more la ghana, we work with cultivating the exhalation and then the BK. Common la

ghana, we work with cultivating the exhalation and then the BK. Common la ghana examples include:

ghana examples include:

Some people, it has to be said, loathe counting their breath. And when we use a metronome—as we often do—they feel “boxed in.” It is very important, therefore, to go into these sorts of practices with an open attitude, to embrace the counting as a support rather than as a prison. Counting can help us to keep focused, it can function as a mirror, and it can be a precision tool for refining and training our breath. It is easy to simply drift off into vague meanderings with the breath if one doesn't count; the rhythm gives the prā āyāma a crispness, a structure and an intensity which may otherwise be lost. For some, an alternative form of counting is to practice with a mantra—repeating the mantra perhaps once on the inhalation and twice on the exhalation (this would be a la

āyāma a crispness, a structure and an intensity which may otherwise be lost. For some, an alternative form of counting is to practice with a mantra—repeating the mantra perhaps once on the inhalation and twice on the exhalation (this would be a la ghana rhythm). This type of prā

ghana rhythm). This type of prā āyāma is called samantraka (literally “with mantra”) and it is very effective.

āyāma is called samantraka (literally “with mantra”) and it is very effective.

The major issue with regard to kāla in prā āyāma is that of over-control. The preordained rhythms can sometimes constrain the breath (and the mind) and the breath then becomes regimented and “audited.” The ideal is to count the breath without overly influencing it, to let it retain its innocence. We need to observe the breath without judgment, give it the freedom to play a little and to surprise us. It's a fine line to walk.

āyāma is that of over-control. The preordained rhythms can sometimes constrain the breath (and the mind) and the breath then becomes regimented and “audited.” The ideal is to count the breath without overly influencing it, to let it retain its innocence. We need to observe the breath without judgment, give it the freedom to play a little and to surprise us. It's a fine line to walk.

khyā—numbering the breath

khyā—numbering the breathThe final point of observation for the breath is sa khyā, number. It may seem trivial or overstated, but simply counting the number of breaths we take is one more important tool in refining and developing our practice. The minimum length for a prā

khyā, number. It may seem trivial or overstated, but simply counting the number of breaths we take is one more important tool in refining and developing our practice. The minimum length for a prā āyāma practice is twelve breaths; anything less is hardly sufficient. By using our thumb as a marker, we can conveniently count these twelve breaths on the inside of our fingers (fig 10.3).

āyāma practice is twelve breaths; anything less is hardly sufficient. By using our thumb as a marker, we can conveniently count these twelve breaths on the inside of our fingers (fig 10.3).

Building longer practices usually involves a vinyāsa krama, so that we increase the intensity of the breath until we reach the goal, and then we step back down to complete the practice. A moderate practice would be 18–30 breaths, whereas a more intense practice might be 40 breaths or longer.

The way we increase the intensity could involve developing either the technique or the rhythm, or indeed, both. However, unless we are experienced practitioners who know our breath well, it is generally advisable to change only one variable at a time (either the technique, the length or the rhythm) as we progress towards our goal. When we build up a practice in this way, we would suggest a minimum count of four breaths (although more commonly six breaths) at each step. It is common to maintain the peak of the practice for twelve breaths—this shows a level of mastery at a particular ratio. It is possible to “fake” six breaths or less, but twelve breaths will show if we have exceeded our capacity.

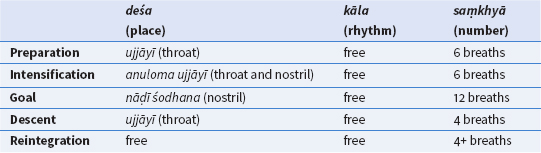

Below are three examples of vinyāsa krama in prā āyāma using sa

āyāma using sa khyā. In the first, there is a development of technique, in the second a development of rhythm, and finally, a development of both. It is important to understand that these are three examples out of many possible structures and they are not to be taken as iconic or definitive. In each, the sa

khyā. In the first, there is a development of technique, in the second a development of rhythm, and finally, a development of both. It is important to understand that these are three examples out of many possible structures and they are not to be taken as iconic or definitive. In each, the sa khyā, or number of breaths at each stage, provides a framing structure.

khyā, or number of breaths at each stage, provides a framing structure.

Here we start with six breaths of ujjāyī to establish a basic breath length. Then we add a further six breaths of nostril control on the exhalation (anuloma ujjāyī) to help clear the nostrils as a preparation for the goal of nā ī śodhana. We maintain our goal for twelve breaths at the peak of the practice. Then we descend in two steps, returning to ujjāyī before finally letting the breath be free for a few breaths. The complete practice is 30 breaths long, making it a moderately long practice.

ī śodhana. We maintain our goal for twelve breaths at the peak of the practice. Then we descend in two steps, returning to ujjāyī before finally letting the breath be free for a few breaths. The complete practice is 30 breaths long, making it a moderately long practice.

In this second example of a vinyāsa krama, we intensify the rhythm. We start with anuloma ujjāyī to establish a good breath length for six breaths, and here we make the exhalation and the inhalation equal. We then increase the exhalation first for another six breaths (remember, the quality of the exhalation is always the key aspect to establish, and is the most important part of the breath). We then reach the goal of an exhalation which is twice as long as the inhalation and we maintain this for twelve breaths, as the main body of the practice. Having completed twelve breaths here, we drop back to a gentle ujjāyī and finish with some free breathing again.

In the final, slightly more complex example, we start with śītalī before introducing a further six breaths with the same rhythm of anuloma ujjāyī, and then six breaths of nā ī śodhana. Staying with the same technique, we now intensify the rhythm by adding kumbhaka after both the inhale and the exhale and maintaining this for twelve breaths. Finally, we drop down again in two steps, first by coming to ujjāyī for four breaths with a lighter rhythm, and finally again letting the breath be free.

ī śodhana. Staying with the same technique, we now intensify the rhythm by adding kumbhaka after both the inhale and the exhale and maintaining this for twelve breaths. Finally, we drop down again in two steps, first by coming to ujjāyī for four breaths with a lighter rhythm, and finally again letting the breath be free.

In all three of these examples, you may notice a radical difference in the quality of the breath and also of the mind by the end of the practice. Having maintained a thorough, rigorous—and gentle—focus on the breath through the application of deśa, kāla and sa khyā, we can very easily move into more meditative practices where there is no control of the breath and the mind is settled.

khyā, we can very easily move into more meditative practices where there is no control of the breath and the mind is settled.