yoga sutra 2.46

sthira-sukham āsanam

With the correct stability in a posture, spaciousness arises

This succinct statement contains three words: sthira, sukha and āsana. The first word, sthira, relates to English words like “stay,” “stability” and “still.” It implies a certain effort required to remain. The second word, sukha, is a beautiful word which can be further divided into its two component syllables: su and kha. When su is used as a prefix in Sanskrit, it indicates something pleasant and comfortable. The word kha refers to space (often specifically the space in the heart—and therefore an emotional experience of space). So sukha literally means a pleasing space, a space in which we are easy and comfortable. (We have already discussed its opposite, du kha, sometimes translated as suffering or pain, in Chapter 4.)

kha, sometimes translated as suffering or pain, in Chapter 4.)

There are many ways to translate this sūtra into English. Here are a few:

The posture (should be) steady and comfortable

—Georg Feuerstein1

Āsana must have the dual qualities of alertness and relaxation

—T.K.V. Desikachar2

The postures of meditation should embody steadiness and ease

—Chip Hartranft3

The posture is firm and comfortable—Frans Moors4

It is important that sthira comes first; after all, sthira is the effort we put into cultivating stability in the posture. If the effort is correct, and appropriate, the fruit will be sukha. Too much effort or wrong kind of effort (for example, gritting your teeth or clenching your jaw) will simply lead to du kha. Likewise, without a certain amount of sthira a posture is not really fully formed: flopping into a posture in a casual and mindless way—even if it looks good from the outside—is not āsana.

kha. Likewise, without a certain amount of sthira a posture is not really fully formed: flopping into a posture in a casual and mindless way—even if it looks good from the outside—is not āsana.

Of all the practices offered by Patañjali, it is undoubtedly āsana that has captured the modern imagination. Indeed, many now equate āsana with yoga; the American yoga teacher Gary Kraftsow reflected that “yoga has been reduced to āsana and āsana has been reduced to stretching.”5 While purists may despair, there is something to be said for āsana as a primary vehicle or methodology of yoga, especially in an increasingly sedentary world where we can easily become displaced from the physical realities of our bodies. At its best, āsana can help us reintegrate and to become more fully embodied.

The dancer Martha Graham once said that “dance is the song of the body.”6 If that is the case, then āsana can be its poetry. We can see this in the very names of postures. Sometimes they take the form of mythological people or animals (vīrabhadra, the mythical warrior; ananta, the mythical serpent; na arāja, the Lord of the Dance; cakravāka, a mythical bird). At other times the name refers to an animal (adho mukhaśvānāsana, downward-facing dog posture; bhuja

arāja, the Lord of the Dance; cakravāka, a mythical bird). At other times the name refers to an animal (adho mukhaśvānāsana, downward-facing dog posture; bhuja gāsana, cobra posture; śalabhāsana, locust posture; si

gāsana, cobra posture; śalabhāsana, locust posture; si hāsana, lion posture; kūrmāsana, turtle posture). Sometimes a natural form is invoked (tā

hāsana, lion posture; kūrmāsana, turtle posture). Sometimes a natural form is invoked (tā āsana, the mountain, or padmāsana, lotus posture). Each of these invites us to express something of the name of the posture in the ways we exercise its form; we give the shape of our body an extra dimension by embodying metaphor.

āsana, the mountain, or padmāsana, lotus posture). Each of these invites us to express something of the name of the posture in the ways we exercise its form; we give the shape of our body an extra dimension by embodying metaphor.

Peter Hersnack took this idea even further. He taught that when we have become fully embodied, the āsana functions “as a sign”—that is, something which points to something beyond itself, which we can't necessarily perceive directly. Peter described how āsana “is work that enables something deep within us to express itself.”7 This beautiful idea evokes something of puru a; the form of the posture is an indication of the truth and reality (sat) of the awareness (cit), and the peaceful joy (ānanda) that is its essence. It is very difficult to capture this in a photograph; but each individual person has the possibility of expressing something of this living essence every time they practice āsana.

a; the form of the posture is an indication of the truth and reality (sat) of the awareness (cit), and the peaceful joy (ānanda) that is its essence. It is very difficult to capture this in a photograph; but each individual person has the possibility of expressing something of this living essence every time they practice āsana.

How do we know what is and what isn't a yoga posture? Is it enough to adopt a particular pose, to place our limbs and trunk in a certain way? When we look at ancient texts on yoga, it comes as quite a surprise to find that āsana, far from being what yoga is all about, has a relatively minor role in traditional practice. Instead, āsana is seen as a means to an end. There are two important functions of various āsana discussed in ancient texts such as the Ha ha Yoga Pradīpikā: firstly, as postures for meditation, and secondly, for manipulating the energies (rather than the anatomy) of the body. The purpose of this purification and energetic manipulation is primarily to promote spiritual experiences, but certain health benefits also arise.

ha Yoga Pradīpikā: firstly, as postures for meditation, and secondly, for manipulating the energies (rather than the anatomy) of the body. The purpose of this purification and energetic manipulation is primarily to promote spiritual experiences, but certain health benefits also arise.

In most ancient Sanskrit texts on Ha ha Yoga (which were composed in the last six hundred years or so) we find that the first function—that of adopting a suitable position for meditative practices—is by far the most common. In the fifteenth-century text, Ha

ha Yoga (which were composed in the last six hundred years or so) we find that the first function—that of adopting a suitable position for meditative practices—is by far the most common. In the fifteenth-century text, Ha ha Yoga Pradīpikā, fifteen postures are described in detail, nine of which relate to cross-legged seated postures in some form. However, many of these are also seen as optimum postures for manipulating energies of the body—particularly along the vertical axis—and thus could be seen as promoting spiritual experiences as well as health.

ha Yoga Pradīpikā, fifteen postures are described in detail, nine of which relate to cross-legged seated postures in some form. However, many of these are also seen as optimum postures for manipulating energies of the body—particularly along the vertical axis—and thus could be seen as promoting spiritual experiences as well as health.

There are some rather extravagant claims made about the health benefits of some of the poses, and these claims should be taken with a pinch of salt. Thus, for example, paścimatānāsana (the seated forward bend) is said to “stimulate the gastric fire, make the loins lean and destroy all the diseases of men” (HYP 1.29).8 The author of the Ha ha Yoga Pradīpikā, Svātmārāma, even went as far as to say that mastery of certain techniques will confer immortality on the diligent practitioner after a certain amount of regular practice: “The knower of yoga, who being steady, has the tongue turned upwards and drinks the soma juice doubtless conquers death in fifteen days” (HYP 3.44). However, as Krishnamacharya is said to have wryly commented, where is Svātmārāma now? You may not achieve immortality, but what is for sure is that an intelligent approach to the practice of āsana will have numerous health benefits. Āsana practice can lead to extraordinary levels of physical prowess and may also function as a wonderful therapeutic tool.

ha Yoga Pradīpikā, Svātmārāma, even went as far as to say that mastery of certain techniques will confer immortality on the diligent practitioner after a certain amount of regular practice: “The knower of yoga, who being steady, has the tongue turned upwards and drinks the soma juice doubtless conquers death in fifteen days” (HYP 3.44). However, as Krishnamacharya is said to have wryly commented, where is Svātmārāma now? You may not achieve immortality, but what is for sure is that an intelligent approach to the practice of āsana will have numerous health benefits. Āsana practice can lead to extraordinary levels of physical prowess and may also function as a wonderful therapeutic tool.

Since the nineteenth century, the number of āsana has dramatically increased, and this is undoubtedly linked to the growth of yoga's popularity in the West. Teachers and schools invented and “discovered” new forms, new ways of coming into postures and new sequences combining postures. If a posture only has an English name and doesn't have a Sanskrit one (e.g., dolphin posture), it is likely to be a relatively recent invention.9

There is undoubtedly a certain one-upmanship that can be seen in the contemporary yoga world when people talk of practicing “classical āsana.” It gives us the impression that a particular form has preordained qualities, and the execution of that form confers a certain level of spirituality and authenticity to the practitioner. In Yoga Body, Mark Singleton assesses the impact of the photograph on the understanding and practice of āsana.10 Singleton argues that the still photograph moves us away from the private sphere and into the public: “Yoga—or a rather particular, modern variant of ha ha yoga—began to be charted and documented through photography with something like the ‘objective stance of the pathologist’ (Budd, 1997:59).” Postures became objectified and the photograph could be used to illustrate their “ideal form” (according to whichever authority one adhered to). This represents a movement from the embodied to the iconic.

ha yoga—began to be charted and documented through photography with something like the ‘objective stance of the pathologist’ (Budd, 1997:59).” Postures became objectified and the photograph could be used to illustrate their “ideal form” (according to whichever authority one adhered to). This represents a movement from the embodied to the iconic.

In B.K.S. Iyengar's hugely influential Light on Yoga,11 the forms of the āsana become reified into the “classical” or iconic postures to which we must aspire. Photos can be useful up to a point, but with them comes the danger that we struggle to emulate an external form rather than understand the essential function of a posture and then intelligently adapt it to suit our own capacities—physical, psychological and emotional. In other words, we must be clear to distinguish function from form such that the form can be appropriately and intelligently modified to respect function.

So, it is difficult to say what is or what is not a yoga posture: looking at photos in a book or magazine is not the answer. However, we will endeavor to first describe certain conditions that need to be met for a bodily posture to be a yoga āsana, and then the various ways in which they can be met. In YS 2.47, Patañjali gives us perhaps the most open, broad, and yet incisive, definition of āsana: sthira-sukham āsanam.

Although we have already begun to explore how sthira is the starting point and sukha is the fruit, we can develop our understanding considerably by seeing how these two qualities differ depending on the āsana, and also how they interact with each other during the different phases of the breath.

Certain postures are intrinsically sukha in their quality. Where is the effort to remain in a posture like śavāsana (the corpse pose, fig 9.1)?

Because the body is completely relaxed, there is no sthira required in the musculature. However, importantly, there must be sthira of the attention, and movement should be contained. For śavāsana to fulfil the conditions of āsana, we must remain present and alert and not just drift off to sleep. Thus, the qualities of sthira and sukha can apply as much to attitude as to physical effort. Let us contrast śavāsana to a much more physically demanding posture like dhanurāsana (the bow, fig 9.2).

Here, tremendous muscular effort is required—the challenge is to approach the posture (both physically and psychologically) sufficiently lightly to let the quality of sukha manifest. Only then does the posture open gently like a flower, so that although it is physically strong, it is also pleasing and comfortable. Just as the strings of a musical instrument require the right amount of tension, so too, each posture requires the right amount of sthira. Too tight is wrong, too loose is wrong; just right produces the perfect note: sukha.

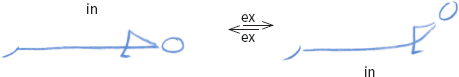

However, it is also important not to think of sthira and sukha as static ingredients in the composition of āsana (Peter Hersnack joked that āsana is not about “30 grams of sthira and 30 grams of sukha”!)12. They do not simply “balance each other,” leading to a sort of mutual cancelling out. This is a way of “domesticating” the postures; instead they should dance together, give birth to one another, be in constant dynamic play with each moment. This interaction between sthira and sukha is mediated by the breath. As we inhale, part of the body remains firm and stable (support), another part moves (direction), opening out into space. Usually on the inhalation the firm part (sthira) is the abdomen, the pelvis and perhaps the legs. This stability allows the spine to lengthen and the space between the head and the pelvis to open (sukha). This reverses as we exhale: often there is an effort to remain open as we exhale lest there is a collapse of space in the trunk. This effort to keep the form open during the exhalation is sthira. Usually this sthira of the exhalation is in the upper part of the body (head and chest and particularly in the sternum), and it allows the abdomen and hips the freedom and space to move.

yoga sutra 2.47

prayatna-śaithilya ananta-samāpattibhyām

Through skillful effort we can loosen the knots of being and let ourselves be supported by breath

This is a fascinating sūtra with layers of meaning and interpretation, but essentially it gives us the methodology for achieving sthirasukham āsanam. It is divided into two parts, prayatna-śaithilya and ananta-samāpatti. Both are essential. The grammatical case-ending (bhyām) implies instrumentality and duality; in other words, both prayatna-śaithilya and ananta-samāpatti are the means by which we achieve sthira and sukha.

Prayatna is a special, committed (pra) type of effort (yatna): it is an effort in which we invest something of ourselves; we are intensely engaged. Śaithilya is the state of being loosened and relaxed. The first part of the sūtra suggests that we make a special effort to come into a state of relaxation, to loosen the knots of our Being (physical, mental, emotional).13 This is effort that transforms itself into ease.

The second part, ananta-samāpatti, is also divided into two parts. Ananta means “without end,” infinite. It can also be used as another metaphor for the breath:14 rather than seeing us as breathing, we see the whole universe as breathing and us as “being breathed.” Breath goes far beyond our individual confines: it is infinite. In this way, we can see ananta as another name for prā a, the vital energy of the universe, the breath of all living creatures. Pat means “to fall”; adding the prefix ā implies that we fall towards something (āpatti). Peter Hersnack suggested that we fall “inwards.” Finally, sam means “together” or “completely.” Thus, samāpatti implies we fall completely, we release into, we move closer towards . . . what? We fall inwards towards the essence of the breath: ananta, prā

a, the vital energy of the universe, the breath of all living creatures. Pat means “to fall”; adding the prefix ā implies that we fall towards something (āpatti). Peter Hersnack suggested that we fall “inwards.” Finally, sam means “together” or “completely.” Thus, samāpatti implies we fall completely, we release into, we move closer towards . . . what? We fall inwards towards the essence of the breath: ananta, prā a.

a.

In one of the most famous and popular stories of Indian mythology, the gods (devas) and the demons (asuras) needed a rope to churn the Milky Oceans to extract the Elixir of Immortality (am ta). As a churning rod, they used Mount Meru, the great mountain which stands at the middle of the world (and is sometimes likened to our spine, forming the central axis). They lifted and inverted it, so that its tip was deep in the ocean. But what could be used as a churning rope that was strong enough, flexible enough and long enough to coil around Mount Meru and be held by those opposite forces, the devas and the asuras? They used Vāsuki, the great Serpent, who is also sometimes equated with the King of the Serpent deities, Ananta. Vāsuki/Ananta is that which enables opposites to work together towards a common goal. Likewise, in the practice of both āsana and prā

ta). As a churning rod, they used Mount Meru, the great mountain which stands at the middle of the world (and is sometimes likened to our spine, forming the central axis). They lifted and inverted it, so that its tip was deep in the ocean. But what could be used as a churning rope that was strong enough, flexible enough and long enough to coil around Mount Meru and be held by those opposite forces, the devas and the asuras? They used Vāsuki, the great Serpent, who is also sometimes equated with the King of the Serpent deities, Ananta. Vāsuki/Ananta is that which enables opposites to work together towards a common goal. Likewise, in the practice of both āsana and prā āyāma, the breath is a mediator which can help to bring opposites to work together towards a common purpose (yoga).15 The breath can bring into relationship the left and the right, the top and the bottom, the front and the back, the axis and the form. Ananta enables a joint project.16

āyāma, the breath is a mediator which can help to bring opposites to work together towards a common purpose (yoga).15 The breath can bring into relationship the left and the right, the top and the bottom, the front and the back, the axis and the form. Ananta enables a joint project.16

Applying this understanding to the sūtra, we can see how ananta-samāpatti can be construed as taking support on the breath/prā a, which in turn supports us. This leads to a profound question regarding the complete sūtra when applied to āsana: what effort can I make (prayatna) to enable the conditions (śaithilya) for me to take support (samāpatti) on that which carries me (ananta/prā

a, which in turn supports us. This leads to a profound question regarding the complete sūtra when applied to āsana: what effort can I make (prayatna) to enable the conditions (śaithilya) for me to take support (samāpatti) on that which carries me (ananta/prā a)? And for those interested in this tradition, when considering this question in relationship to āsana, the answer is clear and simple: to work skillfully with the breath. The work of āsana thereby becomes an exploration and a meditation on prā

a)? And for those interested in this tradition, when considering this question in relationship to āsana, the answer is clear and simple: to work skillfully with the breath. The work of āsana thereby becomes an exploration and a meditation on prā a and its movement within the body.

a and its movement within the body.

yoga sutra 2.48

tato dvandva-anabhighātā

Then we are not overwhelmed by the pairs of opposites

We have seen how, in keeping with Indian tradition, Patañjali divides the world of phenomena into three strands: tamas, rajas and sattva. In āyurveda, the three gu a are fleshed out into twenty qualities called the gurvā

a are fleshed out into twenty qualities called the gurvā i gu

i gu a.17 These twenty qualities are actually ten pairs of opposites: heavy/light; hot/cold; unctuous/dry; gross/subtle; static/dynamic; dense/flowing; slow/fast; soft/hard; smooth/rough; and finally, gelatinous/clear. With these ten pairs, āyurveda is able to describe many of the qualities of prak

a.17 These twenty qualities are actually ten pairs of opposites: heavy/light; hot/cold; unctuous/dry; gross/subtle; static/dynamic; dense/flowing; slow/fast; soft/hard; smooth/rough; and finally, gelatinous/clear. With these ten pairs, āyurveda is able to describe many of the qualities of prak ti—from the cold, hard, sharp qualities of icicles to the soft warmth of feelings of love. Thus, even thoughts, feelings and memories can be described by the gurvādi gu

ti—from the cold, hard, sharp qualities of icicles to the soft warmth of feelings of love. Thus, even thoughts, feelings and memories can be described by the gurvādi gu a in the same way as physical objects.18

a in the same way as physical objects.18

Patañjali goes on to describe the fruit of mastering āsana as the ability not to be overwhelmed by the pairs of opposites. At a physical level, āsana gives us a certain resilience, an ability to withstand the wider fluctuations in external conditions. We are able to remain more tolerant towards extremes of both cold and heat. In certain ascetic traditions, yogis of old would sit unmoving in icy streams, or surrounded by fire in the midday sun. This is an intense form of tapas: the ability to withstand external demands and remain focused on our goals, to stand firm. Even now there are extraordinary stories of yogis who meditate in the freezing cold of the mountains, or remain motionless for days on end.19

Without going to these extremes, we can see how the practice of āsana can help build resilience and stability and thereby render us less susceptible to the vagaries of external conditions. Āsana can also help us with moods, emotions and thoughts. They can help to center us, so that we are less unsettled by success or failure, by happiness or grief. By reducing our tendency to fall out of balance, āsana can optimize our stability and enhance not only our physical, but also our mental health.

One of the hallmarks of this approach to yoga is the focus on the breath. It is precise, logical, considered and refined. For Desikachar, it was of primary importance, and without its sensitive application, something profound is missing from āsana practice. As we have said, breath brings potentially disparate elements into relationship; it yokes mind (attention) and body (form). In this sense, breath is yoga. Desikachar was very insistent that when practicing āsana, body and breath should be synchronized. Certain movements are to be performed as we inhale, others as we exhale. To synchronize the breath is to make the breath at least as long as the movement; ideally we practice in a way that makes the breath “frame” the movement so it starts slightly before the movement begins and finishes just after the body has come to stillness. Furthermore, the breath should remain long, slow and smooth with an even quality throughout. An uneven, ragged breath is a sign that we are overexerting ourselves; the breath thus functions as a mirror.

In YS 2.50, Patañjali introduces us to the components of the breath.20 The order in which he introduces them is significant: first, the exhalation, bāhya v tti (moving outwards); then the inhalation, abhyantara v

tti (moving outwards); then the inhalation, abhyantara v tti (moving inwards) and finally stambha v

tti (moving inwards) and finally stambha v tti (holding the breath, either in or out). We start with the exhalation because it “clears out”; it “wipes the board clean.” The correct exhalation facilitates the subsequent inhalation by providing stability, particularly in the abdomen. The inhalation has then got something to “work against”; the firmness of the abdomen created at the end of the exhalation is like a springboard from which the inhalation can find direction. In this way, the exhalation provides support for the inhalation, and thereby allows a space to open up.

tti (holding the breath, either in or out). We start with the exhalation because it “clears out”; it “wipes the board clean.” The correct exhalation facilitates the subsequent inhalation by providing stability, particularly in the abdomen. The inhalation has then got something to “work against”; the firmness of the abdomen created at the end of the exhalation is like a springboard from which the inhalation can find direction. In this way, the exhalation provides support for the inhalation, and thereby allows a space to open up.

The breath is developed by bodily movements. Forward bends in particular help to lengthen and refine the exhalation. In a forward bend, the hips close, the abdomen compresses and the diaphragm is pushed upwards into the chest cavity. Like the plunger of a syringe, this forces the air up and out, helping us to exhale. Not only does the body help the breath, but the breath helps the body. As we exhale, the body becomes less rigid—think of inflating and then deflating a balloon. Because of this, we are able to soften and relax into forward bends as we exhale. If we take a forward bend on an inhalation, the result is horrible—like driving with the foot on the accelerator and the brake at the same time! Because forward bends support the exhalation so well, they are often the first group of postures we work with. They help us to develop both the stability and the flexibility to deepen our āsana practice and broaden our range of postures.

As with forward bends, the exhalation also facilitates spinal rotation, so we move into twists as we breathe out. In full twists, the abdomen (often) becomes compressed and a degree of flexibility is required. The body is “wrung out” like a dishcloth and this requires us to exhale. Inhaling into a twist is like inhaling into a forward bend: uncomfortable and counterproductive.

Backward bends, where the front of the body opens and lifts, are usually performed as we inhale. The inhalation lifts the sternum, broadens and lifts the ribs and helps us to open into the posture. When the movement of the spine is against gravity (as in bhuja gāsana or śalabhāsana), the inhalation can give the body support: the body can “fly on the thermals” (this also works as we come out of a standing forward bend). Sometimes however, inhaling into a backward bend can cause compression and a feeling of tightness in the back (we are, after all, becoming more rigid as we inhale). In such cases, and particularly when there is back discomfort, weakness or pathology, it can work very well to exhale into backward bends (fig 9.3), and then stay there for the subsequent inhalation, helping to further open and lengthen the posture.

gāsana or śalabhāsana), the inhalation can give the body support: the body can “fly on the thermals” (this also works as we come out of a standing forward bend). Sometimes however, inhaling into a backward bend can cause compression and a feeling of tightness in the back (we are, after all, becoming more rigid as we inhale). In such cases, and particularly when there is back discomfort, weakness or pathology, it can work very well to exhale into backward bends (fig 9.3), and then stay there for the subsequent inhalation, helping to further open and lengthen the posture.

a and apāna vāyu

a and apāna vāyuThe ancients subdivided the energy prā a into five subcategories called the pañca prā

a into five subcategories called the pañca prā a vāyu (“the five wind energies”). These subcategories of energy perform different functions within our system. They are responsible for the healthy functioning of our bodies and indeed it is said that the difference between a live person and a corpse is the presence of prā

a vāyu (“the five wind energies”). These subcategories of energy perform different functions within our system. They are responsible for the healthy functioning of our bodies and indeed it is said that the difference between a live person and a corpse is the presence of prā a. Of these five, two are particularly linked to our breath: prā

a. Of these five, two are particularly linked to our breath: prā a vāyu (rather confusingly this has the same name as the more generic prā

a vāyu (rather confusingly this has the same name as the more generic prā a) and apāna vāyu. They are not exactly the same as the inhalation and the exhalation, but the inhale particularly influences prā

a) and apāna vāyu. They are not exactly the same as the inhalation and the exhalation, but the inhale particularly influences prā a vāyu, and similarly the exhale particularly influences apāna vāyu.

a vāyu, and similarly the exhale particularly influences apāna vāyu.

Prā a vayu's home (prā

a vayu's home (prā asthāna—the place of prā

asthāna—the place of prā a) is located in the chest. As we open and lift from the chest when we breathe in, it is as if the breath originates from the heart, expanding in all directions from its home. Similarly, apāna vayu's home is in the lower abdomen below the navel, where the body becomes firm at the end of an exhalation. Their functions are also different: prā

a) is located in the chest. As we open and lift from the chest when we breathe in, it is as if the breath originates from the heart, expanding in all directions from its home. Similarly, apāna vayu's home is in the lower abdomen below the navel, where the body becomes firm at the end of an exhalation. Their functions are also different: prā a vayu's role is to connect, to link, to open new spaces and directions. Prā

a vayu's role is to connect, to link, to open new spaces and directions. Prā a vāyu is linked to the future; it is an “adventurer.” Apāna vāyu, on the other hand, cleans up. Whereas prā

a vāyu is linked to the future; it is an “adventurer.” Apāna vāyu, on the other hand, cleans up. Whereas prā a vāyu links and is future-orientated, apāna separates and is more past-orientated in the sense that it removes rubbish; it “clears away dirt.” Apāna vāyu is intimately linked to our past because the more that “stuff” accumulates, the harder apāna vāyu has to work—and sometimes it just becomes overwhelmed. Because prā

a vāyu links and is future-orientated, apāna separates and is more past-orientated in the sense that it removes rubbish; it “clears away dirt.” Apāna vāyu is intimately linked to our past because the more that “stuff” accumulates, the harder apāna vāyu has to work—and sometimes it just becomes overwhelmed. Because prā a vāyu and apāna vāyu “have the same bank card,” as it were, they draw from the same energetic account.21 If apāna vāyu is overspending, prā

a vāyu and apāna vāyu “have the same bank card,” as it were, they draw from the same energetic account.21 If apāna vāyu is overspending, prā a vāyu has fewer resources. When we are overrun with accumulated waste from the past which we haven't got rid of, we have less energy for new ventures and experiences: we are just too tired. This is another reason why we work on the exhale—and thus apāna vāyu—first.

a vāyu has fewer resources. When we are overrun with accumulated waste from the past which we haven't got rid of, we have less energy for new ventures and experiences: we are just too tired. This is another reason why we work on the exhale—and thus apāna vāyu—first.

While postures that open the chest and favor the inhalation can be classified as “prā a” postures (also known as b

a” postures (also known as b

ha

ha a kriyā), and postures favoring the exhalation can be classified as “apāna” postures (also known as la

a kriyā), and postures favoring the exhalation can be classified as “apāna” postures (also known as la ghana kriyā), not all breathing works with the same energetic intensity and efficiency. It is useful to distinguish between two types of inhalation and two types of exhalation.

ghana kriyā), not all breathing works with the same energetic intensity and efficiency. It is useful to distinguish between two types of inhalation and two types of exhalation.

An inhalation that fills is very different from an inhalation that opens: it occupies space rather than opening it. The more we fill as we breathe in, the tighter we become and at the end of the breath we feel completely blocked: there is nowhere left to go. This is a crude inhalation that creates rigidity as it grasps and holds on. However, we can also inhale in a much more subtle way in which we “open from inside” rather than “filling from outside,” and this gives a completely different feel to the practice. It is as if we could go on breathing in forever: the movement feels like a continuous yielding and opening from within. Interestingly, when a baby is born, the lungs and trachea are “flat packs”—they are vacuum-sealed. Our first breath is thus not a “taking in” but an “opening up.” We open to the world to receive it rather than simply filling up from outside. This opening gives prā a vāyu the space to do its work.22

a vāyu the space to do its work.22

We can also distinguish between an exhalation that “collapses” and one that “separates.” Peter Hersnack joked that exhalation isn't simply “a retention of the breath with a slow puncture.” This just leads to deflation, and apāna vāyu is unable to function efficiently, because there is no space for it to circulate. In order for apāna vāyu to be able to function there needs to be a differentiation between the exhalation and the form of the posture; it is as if we hold the form open as we breath out and, like a receding tide, the exhalation withdraws back to its home. If we vacuum clean a rug that is lying on a wooden floor, we have to hold the rug still in order for the cleaner to work (that is, to separate the dirt from the rug). If we don't, then the rug will simply move with the vacuum cleaner and there will be no separation. This is the equivalent of an exhalation that collapses: nothing happens on an energetic level. In both of these examples (an inhalation which opens and an exhalation which remains open), there is a palpable distinction between body and breath. They interact with each other in a profound way, but they also remain free. In the contrasting types of breath, where the inhalation fills and the exhalation collapses, body and breath are “glued” to each other, and are thereby imprisoned.

The basic methodology of breathing in āsana within this tradition is ujjāyī, sometimes called “throat control breathing.” Desikachar described ujjāyī as “that which clears the throat and masters the chest.”23 Its literal meaning is “giving mastery over the upward (movement)” and at a bodily level, ujjāyī acts as an expectorant, helping to dry excessive dampness from the trachea and thereby “master” the chest.

In ujjāyī, we create a restriction in the throat and there is a gentle hissing sound—it feels as if we are breathing directly in and out through the throat. This gentle friction, created by the turbulence as the flow of air passes through the restriction, can be used as a support for the movement, for the breath and for the attention. As a support for the movement, ujjāyī gives “body to the breath”: it makes the breath more substantial and helps the body float on its presence. As a support for the breath, ujjāyī helps to lengthen the breath, to make it more subtle and refined. Very importantly, we make a distinction between ujjāyī and the breath: ujjāyī is a tool which refines and controls the breath, but they are not the same. At its most subtle, we could even say that ujjāyī is a sign of the breath, an indication of the quality of the breath. Finally, as a support for the mind, ujjāyī gives the attention a tangible place to settle upon; it creates a gravitational pull that helps to keep the mind from scattering.

As ujjāyī is used throughout āsana practice, it becomes the default breath. But—and it's a big but—it has the potential to be abused. If ujjāyī becomes too habitual, we can easily switch off to it and it becomes an “alibi”: “Yes, I was present! I was doing ujjāyī!” While it can really help new practitioners to focus and refine their āsana practice, there is a potential danger for any experienced practitioner that it simply becomes a habit. For this reason, it may be helpful to use images and suggestions to keep our relationship with ujjāyī fresh. Ujjāyī can be seen as “a place of contact,” as “touching the whole body and not just the throat,” or indeed “a caress not a control.” It is easy to make the breath too rigid. Instead, we should let the breath play a little, to watch the interaction between breath and body and let that interaction be surprising sometimes, so that one moves in one way and the other in another. This helps maintain a freshness and joy with each breath we take in our āsana practice. Our ability to habituate, appropriate and abuse our relationship with what begins as being a genuine support is everywhere—yoga easily becomes sa yoga!

yoga!

Finally, although ujjāyī is the default breath in our practice (particularly in āsana and prā āyāma), it should not be practiced throughout the session nor as the default breath in our daily lives. When we are resting in between postures, or in śavāsana, for example, we should be able to let the breath be natural and unforced. We should also appreciate that in meditation, the breath is usually free and it is important, therefore, to be able to let it go as appropriate.

āyāma), it should not be practiced throughout the session nor as the default breath in our daily lives. When we are resting in between postures, or in śavāsana, for example, we should be able to let the breath be natural and unforced. We should also appreciate that in meditation, the breath is usually free and it is important, therefore, to be able to let it go as appropriate.