yoga sutra 3.4

trayam ekatra sa yama

yama

When the three stages of meditation are practiced together as a single process, this is sa yama

yama

The process of meditation is described by the three inner limbs, dhāra ā, dhyāna and samādhi. These three steps describe a process and should be considered as a continuum rather than as discrete or separate practices. When they come together as one, this process of meditative absorption is known as sa

ā, dhyāna and samādhi. These three steps describe a process and should be considered as a continuum rather than as discrete or separate practices. When they come together as one, this process of meditative absorption is known as sa yama, literally “complete restraint” of the mind. This is consistent with the understanding of nirodha as “directing the mind in a chosen direction and restraining (nirodha) all activities of the mind (citta v

yama, literally “complete restraint” of the mind. This is consistent with the understanding of nirodha as “directing the mind in a chosen direction and restraining (nirodha) all activities of the mind (citta v tti) that are contrary to that direction.” Although this may appear to be a very rigid, controlled process, it is actually a delicate play between abhyāsa and vairāgya, requiring a high level of vairāgya.

tti) that are contrary to that direction.” Although this may appear to be a very rigid, controlled process, it is actually a delicate play between abhyāsa and vairāgya, requiring a high level of vairāgya.

Dhāra ā is the first step in the process and is defined in YS 3.1 as “binding the mind to a single place (deśa).” The essential quality of dhāra

ā is the first step in the process and is defined in YS 3.1 as “binding the mind to a single place (deśa).” The essential quality of dhāra ā is the intention to link the mind to a chosen object or a field of enquiry. In dhāra

ā is the intention to link the mind to a chosen object or a field of enquiry. In dhāra ā the link with the deśa is stable, and the attention is focused.

ā the link with the deśa is stable, and the attention is focused.

The second of the inner limbs, dhyāna, is characterized by a deepening connection to the field of enquiry so that we start to gain new insight. In dhyāna our perceptions and mental responses link up with a new level of coherence and freshness. Dhyāna is characterized both by the citta v tti flowing towards the deśa (indicating the stability of the link), and also by their return to the mind (facilitating new insight or perception).

tti flowing towards the deśa (indicating the stability of the link), and also by their return to the mind (facilitating new insight or perception).

The pinnacle of the meditative process, and the last of the eight limbs, is samādhi (literally “putting together completely”). There are two basic levels of “yogic” samādhi and it is the first, sabīja samādhi, that is being referred to here (the other is nirbīja samādhi). Sabīja samādhi is directed meditation (i.e., a meditation in which there is an object or field of enquiry), while nirbīja samādhi does not require an object.1

Patañjali defines sabīja samādhi as having two key characteristics. The first is that the essential nature of the object of meditation shines forth, implying that this is an extraordinary level of perception and that the object fills the mind. The second follows from this: that for the duration of the samādhi, it is as if any sense of separation between meditator and object of meditation disappears, and there is a feeling of “oneness.” The sūtra emphasizes that this is an “as if” experience, so it only lasts for the duration of the samādhi.

Sa yama is when dhāra

yama is when dhāra ā, dhyāna and samādhi become one deep, seamless process. The traditional commentators explain that sa

ā, dhyāna and samādhi become one deep, seamless process. The traditional commentators explain that sa yama is the process of meditation practiced with the same object in mind for a long period of time. This creates a habitual pattern for the mind (sa

yama is the process of meditation practiced with the same object in mind for a long period of time. This creates a habitual pattern for the mind (sa skāra) that allows the meditator to achieve an extraordinary level of insight with respect to the object of enquiry. This is said to be the realm of true wisdom (YS 3.5). It is from such a deep level of meditative enquiry that the “special powers” (siddhi) arise. These powers form a large part of Chapter 3 of the Yoga Sūtra and are the most extensive topic within the text.2

skāra) that allows the meditator to achieve an extraordinary level of insight with respect to the object of enquiry. This is said to be the realm of true wisdom (YS 3.5). It is from such a deep level of meditative enquiry that the “special powers” (siddhi) arise. These powers form a large part of Chapter 3 of the Yoga Sūtra and are the most extensive topic within the text.2

Yoga is samādhi, according to Vyāsa in his commentary to the very first sūtra (YS 1.1). In YS 3.4 we are introduced to a new term, sa yama—the culmination of the meditative process described by the three final limbs of the eight limbs of yoga: dhāra

yama—the culmination of the meditative process described by the three final limbs of the eight limbs of yoga: dhāra ā, dhyāna and samādhi. Breaking this down into three separate terms is for the convenience of explanation only: in truth, the meditative process is continuous and may not even involve all three “limbs”—indeed samādhi may be something that we never or rarely experience. But Patañjali defines sa

ā, dhyāna and samādhi. Breaking this down into three separate terms is for the convenience of explanation only: in truth, the meditative process is continuous and may not even involve all three “limbs”—indeed samādhi may be something that we never or rarely experience. But Patañjali defines sa yama as the process of meditation where all the three steps are present together “as one.” He presents this as the route to gaining insight and wisdom, and thereby gaining certain mastery or control. The yoga tradition is full of stories of yogis who have extraordinary powers (siddhi), such as the ability to become invisible, to float in the air or travel great distances almost instantly.

yama as the process of meditation where all the three steps are present together “as one.” He presents this as the route to gaining insight and wisdom, and thereby gaining certain mastery or control. The yoga tradition is full of stories of yogis who have extraordinary powers (siddhi), such as the ability to become invisible, to float in the air or travel great distances almost instantly.

Whether or not we believe such claims, meditation is clearly seen as the route to developing insight into the nature of things and, ultimately, into the nature of ourselves. When the mind is honed to focus with total clarity and lack of projection, our potential for insight is extraordinary. This is something we can all readily experience: in quiet moments when the mind is uncluttered and clear, new and profound insights arise.

A typical yoga class consists largely of āsana, perhaps with ten minutes of prā āyāma, and little, if any, seated meditation. And yet, according to Vyāsa, yoga is meditation and Patañjali himself defines yoga as “citta v

āyāma, and little, if any, seated meditation. And yet, according to Vyāsa, yoga is meditation and Patañjali himself defines yoga as “citta v tti nirodha” in YS 1.2. If we are serious about pursuing yoga in the spirit of the Yoga Sūtra, we should therefore consider the significance of seated meditation practice.

tti nirodha” in YS 1.2. If we are serious about pursuing yoga in the spirit of the Yoga Sūtra, we should therefore consider the significance of seated meditation practice.

Our training in this tradition has undoubtedly focused on the practice of āsana and prā āyāma, with much less emphasis on seated meditation. But does the meditative process apply only to formal seated meditation, or can it apply to the other practices such as āsana and prā

āyāma, with much less emphasis on seated meditation. But does the meditative process apply only to formal seated meditation, or can it apply to the other practices such as āsana and prā āyāma as well? In both āsana and prā

āyāma as well? In both āsana and prā āyāma the principle intention is to engage the mind and our approach has been to make the meditative engagement of the mind the most important aspect. We are not suggesting that āsana and prā

āyāma the principle intention is to engage the mind and our approach has been to make the meditative engagement of the mind the most important aspect. We are not suggesting that āsana and prā āyāma replace seated meditation practices, but that they can also be meditative practices in which the basic principles, and those of the “inner limbs,” can apply.

āyāma replace seated meditation practices, but that they can also be meditative practices in which the basic principles, and those of the “inner limbs,” can apply.

“In both āsana and prā āyāma, the principle intention is to engage the mind.”

āyāma, the principle intention is to engage the mind.”

Sa yama is explained by Vyāsa as the process of deep meditation (dhāra

yama is explained by Vyāsa as the process of deep meditation (dhāra ā, dhyāna and samādhi) towards the same object of enquiry over a long period—weeks, months or even years. The siddhi imply complete knowledge of something which leads to its mastery. This requires that it is explored fully “from all sides.”3 Time and repeated practice are necessary. The Yoga Sūtra states that the mind works through habitual patterns (sa

ā, dhyāna and samādhi) towards the same object of enquiry over a long period—weeks, months or even years. The siddhi imply complete knowledge of something which leads to its mastery. This requires that it is explored fully “from all sides.”3 Time and repeated practice are necessary. The Yoga Sūtra states that the mind works through habitual patterns (sa skāra), well-worn grooves that we can slot into with ease. Many of these are unconscious and indeed unhelpful in our lives. But sa

skāra), well-worn grooves that we can slot into with ease. Many of these are unconscious and indeed unhelpful in our lives. But sa skāra can also be helpful. Krishnamacharya stated that yoga practice itself is a sa

skāra can also be helpful. Krishnamacharya stated that yoga practice itself is a sa skāra. We should understand that meditation is also a sa

skāra. We should understand that meditation is also a sa skāra; in short, it gets easier with practice.

skāra; in short, it gets easier with practice.

We can apply the principles of sa yama to many areas of life. Observation in teaching yoga can have something of the spirit of sa

yama to many areas of life. Observation in teaching yoga can have something of the spirit of sa yama. A teacher who brings this meditative quality to the observation of their students can achieve extraordinary levels of perception—as we have experienced ourselves with our teachers. A highly skilled and experienced surgeon could also be an example of someone who has a siddhi resulting from dedicated sa

yama. A teacher who brings this meditative quality to the observation of their students can achieve extraordinary levels of perception—as we have experienced ourselves with our teachers. A highly skilled and experienced surgeon could also be an example of someone who has a siddhi resulting from dedicated sa yama, focused practice and study in a specific area over a long period of time resulting in extraordinary knowledge and mastery.

yama, focused practice and study in a specific area over a long period of time resulting in extraordinary knowledge and mastery.

In Chapter 3 of the Yoga Sūtra, Patañjali lists many possibilities for sa yama and its fruits. Although this part of the Yoga Sūtra can seem somewhat opaque, even bizarre, and the list of different sa

yama and its fruits. Although this part of the Yoga Sūtra can seem somewhat opaque, even bizarre, and the list of different sa yama and their fruits rather random, there is an internal logic. The list mirrors the evolutionary structure of the world as proposed by the Sā

yama and their fruits rather random, there is an internal logic. The list mirrors the evolutionary structure of the world as proposed by the Sā khya system.4 Sā

khya system.4 Sā khya, as we discussed in Chapter 7, is the sister philosophy to yoga and provides a foundation for understanding the world.5 Sā

khya, as we discussed in Chapter 7, is the sister philosophy to yoga and provides a foundation for understanding the world.5 Sā khya proposes a system that classifies the world into twenty-five essential principles (tattva) and many of the siddhi can be understood as the result of mastering these principles.

khya proposes a system that classifies the world into twenty-five essential principles (tattva) and many of the siddhi can be understood as the result of mastering these principles.

ā: Stabilizing the link

ā: Stabilizing the link

yoga sutra 3.1

deśa bandha cittasya dhāra

cittasya dhāra a

a

Dhāra ā involves binding the mind to a place or location

ā involves binding the mind to a place or location

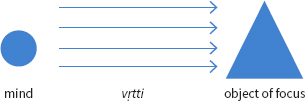

In dhāra ā, we focus the mind on a chosen object or field of enquiry (deśa) and maintain that link for some time. This requires intention and effort. The word dhāra

ā, we focus the mind on a chosen object or field of enquiry (deśa) and maintain that link for some time. This requires intention and effort. The word dhāra ā comes from the Sanskrit root dh

ā comes from the Sanskrit root dh meaning “to hold” or “support”; the very word itself implies an intention to hold the object of focus. It is often translated as “concentration,” although this carries with it unhelpful associations of hard work and a furrowed brow. For dhāra

meaning “to hold” or “support”; the very word itself implies an intention to hold the object of focus. It is often translated as “concentration,” although this carries with it unhelpful associations of hard work and a furrowed brow. For dhāra ā to evolve to the next level, dhyāna, such tightness is counterproductive and actually blocks the process it is trying to facilitate.

ā to evolve to the next level, dhyāna, such tightness is counterproductive and actually blocks the process it is trying to facilitate.

Dhāra ā: V

ā: V tti are focused and the mind is stable

tti are focused and the mind is stable

Many people are put off meditation because they feel that they cannot do it and fail when they try. They cannot maintain focus for any length of time, let alone “empty” their minds (perhaps one of the least helpful instructions for anyone trying to meditate). Meditation involves vinyāsa krama: it is a gradual process. We should approach it with compassion towards ourselves and our unsteady minds, accepting that movement in the mind is natural and not something intrinsically bad. Training the mind is a little like training a puppy: it requires great patience and a firm, kind guiding hand. Repetition is key, coming back to the practice without anger and frustration, but with an even-handed persistence.

In most classes and workshops, insufficient attention is given to seriously maintaining focus. Although students know that it is part of the practice, it easily becomes secondary to the physicality and feel-good factor that the practice can bring. But dhāra ā requires diligence and persistence, and is applicable to all aspects of the practice, not just formal meditation. Dhāra

ā requires diligence and persistence, and is applicable to all aspects of the practice, not just formal meditation. Dhāra ā requires us to switch on, not switch off, and this is an active process necessitating intention, effort and vigilance towards all the subtle attitudes and judgments that we bring to the process. It is almost inevitable that at some point our attitude will become too tight: it is a fine line between too much effort and too little.

ā requires us to switch on, not switch off, and this is an active process necessitating intention, effort and vigilance towards all the subtle attitudes and judgments that we bring to the process. It is almost inevitable that at some point our attitude will become too tight: it is a fine line between too much effort and too little.

It is easy to feel frustrated when we find it difficult to stop the mind from flitting from here to there. But it's worth remembering that because the mind is nothing but gu a, and their nature is dynamic, it is only natural for the mind to move. In YS 3.9, Patañjali states that the mind has two possibilities: that of “emergence” (vyutthāna) and that of “stillness” (nirodha). Emergence is defined as any state of mind in which there are v

a, and their nature is dynamic, it is only natural for the mind to move. In YS 3.9, Patañjali states that the mind has two possibilities: that of “emergence” (vyutthāna) and that of “stillness” (nirodha). Emergence is defined as any state of mind in which there are v tti (ideas, thoughts, feelings and memories) that rise up and become visible. What is less obvious, however, is that even in a state of nirodha there is actually movement, albeit more subtle and therefore less perceptible. The mind appears static in nirodha because there is the appearance of only one v

tti (ideas, thoughts, feelings and memories) that rise up and become visible. What is less obvious, however, is that even in a state of nirodha there is actually movement, albeit more subtle and therefore less perceptible. The mind appears static in nirodha because there is the appearance of only one v tti (or image) but in fact, it is a continuous repetition of a single image—like a number of still frames of the same shot in a film. Both of these states, vyutthāna and nirodha, are largely habitual (they are sa

tti (or image) but in fact, it is a continuous repetition of a single image—like a number of still frames of the same shot in a film. Both of these states, vyutthāna and nirodha, are largely habitual (they are sa skāra), and so the more we practice, the more easily we can train our minds to focus peacefully—and thereby move from vyutthāna to nirodha. It is a matter of gradual and gentle training.

skāra), and so the more we practice, the more easily we can train our minds to focus peacefully—and thereby move from vyutthāna to nirodha. It is a matter of gradual and gentle training.

Although dhāra ā requires us to have an intention to “bind” or “hold” the mind and to keep our attention stable, this is only the starting point. Dharma (which comes from same root dh

ā requires us to have an intention to “bind” or “hold” the mind and to keep our attention stable, this is only the starting point. Dharma (which comes from same root dh as dhāra

as dhāra ā) is a complex word simply summed up as “our purpose and responsibilities in life.” In the Bhagavad Gītā, following and fulfilling our dharma is considered a route to the highest yoga. There is a reciprocal relationship between a person and their dharma: if someone can “hold” their dharma—follow their path diligently and fulfil their obligations—then their dharma will “hold” them. Initially we actively carry our dharma, but then it begins to carry us: to take support on something, we must give support to it. This is a very helpful way to think about our relationship towards a deśa, which is effectively a support for our mind.

ā) is a complex word simply summed up as “our purpose and responsibilities in life.” In the Bhagavad Gītā, following and fulfilling our dharma is considered a route to the highest yoga. There is a reciprocal relationship between a person and their dharma: if someone can “hold” their dharma—follow their path diligently and fulfil their obligations—then their dharma will “hold” them. Initially we actively carry our dharma, but then it begins to carry us: to take support on something, we must give support to it. This is a very helpful way to think about our relationship towards a deśa, which is effectively a support for our mind.

During dhāra ā we begin by actively holding our attention towards the deśa, “binding the mind.” But in order to allow the deśa to fully act as a support, we must relax and open our mind to become receptive. This takes us into the realm of dhyāna, but it comes from the attitude which we bring to dhāra

ā we begin by actively holding our attention towards the deśa, “binding the mind.” But in order to allow the deśa to fully act as a support, we must relax and open our mind to become receptive. This takes us into the realm of dhyāna, but it comes from the attitude which we bring to dhāra ā. The single-direction arrows in the diagram, representing the stable focus of all mental activity towards the deśa, are really only the starting point for dhāra

ā. The single-direction arrows in the diagram, representing the stable focus of all mental activity towards the deśa, are really only the starting point for dhāra ā. Peter Hersnack described how as the object of meditation deepens, the object can become “guru.” Here the word has an interesting double meaning: both “heavy” and also “teacher.” On the one hand, the gravitational pull of the object increases (it becomes heavy) so that it both begins to hold us and increasingly fills our consciousness with its nature and qualities. But also, we learn something new and we are changed; the object functions like a teacher or guru.

ā. Peter Hersnack described how as the object of meditation deepens, the object can become “guru.” Here the word has an interesting double meaning: both “heavy” and also “teacher.” On the one hand, the gravitational pull of the object increases (it becomes heavy) so that it both begins to hold us and increasingly fills our consciousness with its nature and qualities. But also, we learn something new and we are changed; the object functions like a teacher or guru.

The interplay between actively holding the mind's focus and allowing it to be receptive is like the abhyāsa and vairāgya of meditation. If we hold on to the object too tightly and intently, there is a danger that we simply project our existing associations and concepts onto it. There is no space for the reality of the object to touch us. However, if the link with the object is stable, and we allow ourselves to let go of expectations and preconceptions, the mind may open up to what is actually there.

Deśa is also a concept that requires some careful explanation. Deśa is literally “a place” and in Vyāsa's commentary examples are given that are locations, in the body, such as the navel or the tip of the nose. The word is also used in the sūtra on prā āyāma (YS 2.50) and similarly refers to a physical location: the location where the breath is experienced in the body. However, the examples of sa

āyāma (YS 2.50) and similarly refers to a physical location: the location where the breath is experienced in the body. However, the examples of sa yama given in Chapter 3 of the Yoga Sūtra are much more diverse and not limited to physical locations. Deśa may be any focal point for the mind, including objects of meditation such as the breath itself, a mantra, a visualization of the sun or even a deity, a question for contemplation, or a physical or imagined symbol. There are endless possibilities.

yama given in Chapter 3 of the Yoga Sūtra are much more diverse and not limited to physical locations. Deśa may be any focal point for the mind, including objects of meditation such as the breath itself, a mantra, a visualization of the sun or even a deity, a question for contemplation, or a physical or imagined symbol. There are endless possibilities.

The word is etymologically linked to the Sanskrit root diś, meaning “to point.” From this perspective, deśa is that which points to something beyond itself, like a road sign to a nearby town. Many traditional objects of meditation, such as sacred symbols, mantras, and even deity visualizations are deśa in this sense: they invite the meditator towards a reality or truth that is greater than the symbol itself.

yoga sutra 3.2

tatra pratyayaikatānatā dhyānam

From that (dhāra a), our perceptions become continuous and integrate: this is dhyāna

a), our perceptions become continuous and integrate: this is dhyāna

If we were to choose a single Sanskrit equivalent to the English word “meditation” it would be dhyāna. Dhyāna comes from the Sanskrit root dhyā, meaning “to think about” or “contemplate.” In Sanskrit literature, dhyāna is used to refer to both meditation and also the culmination of the meditative process particularly in texts predating the Yoga Sūtra. Samādhi is a newer term used in the Yoga Sūtra, texts of a similar age, and subsequent texts.

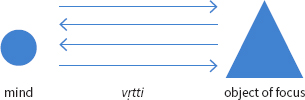

In Patañjali's sequence of “inner limbs,” dhyāna refers to the deepening of the meditative process. It is a two-way process whereby the attention is maintained towards the object of meditation and something is received from it. In dhyāna, it is as if the object communicates something of itself to us and we begin to gain insight into its true nature.

Dhyāna: As involvement deepens, new insights arise

The word tatra in YS 3.2 means “there,” and it refers us back to the previous sūtra and the state of dhāra ā. Dhyāna follows from the foundation of dhāra

ā. Dhyāna follows from the foundation of dhāra ā. The defining feature of dhyāna is indicated by the phrase pratyaya eka tānatā, which describes a particular state of the pratyaya, the ideas that arise in the mind in response to the meditation.

ā. The defining feature of dhyāna is indicated by the phrase pratyaya eka tānatā, which describes a particular state of the pratyaya, the ideas that arise in the mind in response to the meditation.

Pratyaya is a word that comes from the root i meaning “to go,” with a prefix prati that indicates a reversal or return. Thus, pratyaya are ideas that arise in the mind in response to “a going and a coming back” (hence the arrows in both directions in our diagram). In the yogic view of perception there is a movement of prā a outwards towards an object of perception and a return movement of prā

a outwards towards an object of perception and a return movement of prā a carrying an impression or perception. In dhyāna, the pratyaya are said to be eka tānatā; they create a single continuity or interconnection.

a carrying an impression or perception. In dhyāna, the pratyaya are said to be eka tānatā; they create a single continuity or interconnection.

Vyāsa understands the eka tānatā to be the continuity of the connection with the object. Whereas in dhāra ā there is stability, but also the possibility of interruption, in dhyāna the link is continuous and not subject to distraction or interruption. Dhāra

ā there is stability, but also the possibility of interruption, in dhyāna the link is continuous and not subject to distraction or interruption. Dhāra ā is analogous to a stream of water droplets with small spaces between each droplet, whereas in dhyāna the flow of attention is continuous like pouring oil or honey.

ā is analogous to a stream of water droplets with small spaces between each droplet, whereas in dhyāna the flow of attention is continuous like pouring oil or honey.

There is another dimension to eka tānatā which is more related to the connection between the ideas that arise in the mind. Usually our perception of things is distorted and overlaid by assumptions, memories and expectations. Peter Hersnack referred to this as “the imperialism of meaning.” Rather than impose our beliefs on the world—as an imperial or colonial power might—in dhyāna, our pratyaya begin to connect up in new ways that reflect the reality of what we are encountering. Our insights and perceptions become more consistent with the singular reality of the object in the here and now: eka tānatā.

The practice of meditation is not like traveling towards a destination through a tunnel. It evolves organically, with moments of focus, moments of receptivity, maybe something akin to a new insight and lots of drifting around with obscure peripheral thoughts. Lots of distraction, lots of reconnecting. Don't be concerned if you don't appear to be “getting anywhere.” Even at this level, the concepts of dhāra ā and dhyāna have a crucial role to play.

ā and dhyāna have a crucial role to play.

When meditating, Desikachar said he always made sure to have a pencil and notepad in his shirt pocket. As the mind settles, it is as if the threshold between conscious and unconscious thought becomes more permeable and all kinds of small insights, ideas or useful thoughts can arise. This peripheral bubbling of the mind can be both a distraction and a source of inspiration and insight, so we should acknowledge it as a common feature of the conversation that is dhyāna.

yoga sutra 3.3

tadeva artha mātra nirbhāsam svarūpa śūnyamiva samādhi

When the true nature of the object reveals itself, and fills the mind as if we are no longer present, that is samādhi

The culmination of the meditative process is called samādhi. The first word, tadeva, means “there/that indeed” and links to the previous sūtra concerning dhyāna. Samādhi arises out of dhyāna and can be understood as a particular state of dhyāna, rather than something completely different. As we have said, prior to the Yoga Sūtra, the term dhyāna was used to describe the highest states of meditation and it is only after the Yoga Sūtra that the term samādhi became more widely used.

Samādhi: Total identification with object leads to complete understanding

Samādhi means “to go into,” “go together,” “put together” or be “deeply rooted.” In samādhi we go into the object of meditation fully, become totally absorbed in it, and everything in our understanding and experience of the object becomes complete. The mind is deeply rooted and stable. Patanjali defines samādhi more specifically in YS 3.3 by describing two fundamental conditions that apply.

The first concerns the phrase artha mātra nirbhāsam, “the essential nature of the object alone shines forth.” In samādhi our comprehension and insight become complete and this illuminates the mind so that nothing else is present.

The second, svarūpa śūnyam iva, means “as if empty of our own form.” This follows as a consequence of the first and refers to the experience of losing our sense of separateness from the object of meditation. This state lasts only as long as samādhi—from a few fleeting moments to longer, sustained periods for more advanced yogis.

Keeping in mind these two conditions—deep absorption and the loss of any sense of separateness—is the key to understanding the meaning of samādhi in the Yoga Sūtra.

As we explored in Chapter 2, Vyāsa presents five states of mind. The first three are:

ipta)—characterized by an excess of rajas

ipta)—characterized by an excess of rajas ha)—characterized by an excess of tamas

ha)—characterized by an excess of tamas ipta)—characterized by instability

ipta)—characterized by instabilityThese states all have the potential for a “sort of” samādhi—that is, a type of absorption. We can be truly absorbed in our obsessive activity (excess rajas), or stuck in dullness (excess tamas). And we may have moments of insight (sattva) when we are in the third state (vik ipta), but the state is fickle. Because sattva does not dominate, and there is no stability, none of these is a yoga samādhi; they are like false samādhi.

ipta), but the state is fickle. Because sattva does not dominate, and there is no stability, none of these is a yoga samādhi; they are like false samādhi.

Vyāsa does go on to elaborate two further states, which are yoga samādhi: ekāgra and niruddha. In the first, we focus on an object of meditation; it is therefore sabīja (“with seed”). In the second, there is no external object of support and the state is thus called nirbīja, “without seed.” In Chapter 1 of the Yoga Sūtra, Patañjali directly refers to these two levels, which he calls sa prajñāta and anya (“the other one”) respectively.

prajñāta and anya (“the other one”) respectively.

yoga sutra 1.17

vitarka vicāra ānanda asmitārūpa anugamāt sa prajñāta

prajñāta

Sa prajñāta samādhi has four levels: discursive thought, subtle insight, bliss and identification

prajñāta samādhi has four levels: discursive thought, subtle insight, bliss and identification

Sa prajñāta, the first level of samādhi, is “with seed” and even here there is a hierarchy—one state of samādhi evolves into the next (anugamāt). Its four levels, vitarka, vicāra, ānanda and asmitārūpa are complex technical terms in this context, but we can understand them in a simple way as each being a more subtle form of samādhi than its precursor. In vitarka there is a comprehension of the gross form of the object of contemplation and this is accompanied by some discursive thought. It is looking at the object from various angles. This evolves into vicāra, where we see something of the hidden depths of an object, aspects which are not apparent initially. Vicāra thus takes us to a deeper comprehension of an object. With this evolves a feeling of joy (ānanda); our minds are profoundly contented as they are focused, engaged and working at their optimal level. As a result of this process, our sense of self shifts away from our constructed self (asmitā kleśa) towards the simplicity and truth of the feeling of simply being alive and aware (asmitā rūpa). We could see this deepening of the process of samādhi as a sort of “subtle form of sa

prajñāta, the first level of samādhi, is “with seed” and even here there is a hierarchy—one state of samādhi evolves into the next (anugamāt). Its four levels, vitarka, vicāra, ānanda and asmitārūpa are complex technical terms in this context, but we can understand them in a simple way as each being a more subtle form of samādhi than its precursor. In vitarka there is a comprehension of the gross form of the object of contemplation and this is accompanied by some discursive thought. It is looking at the object from various angles. This evolves into vicāra, where we see something of the hidden depths of an object, aspects which are not apparent initially. Vicāra thus takes us to a deeper comprehension of an object. With this evolves a feeling of joy (ānanda); our minds are profoundly contented as they are focused, engaged and working at their optimal level. As a result of this process, our sense of self shifts away from our constructed self (asmitā kleśa) towards the simplicity and truth of the feeling of simply being alive and aware (asmitā rūpa). We could see this deepening of the process of samādhi as a sort of “subtle form of sa yama”: just as dhāra

yama”: just as dhāra ā evolves into dhyāna and then samādhi, so vitarka evolves into vicāra and then to ānanda and finally asmitā rūpa.6

ā evolves into dhyāna and then samādhi, so vitarka evolves into vicāra and then to ānanda and finally asmitā rūpa.6

yoga sutra 1.18

virāmapratyaya abhyāsapūrva sa

sa skāraśe

skāraśe a

a anya

anya

The other (level of samādhi), arising from the practice of the previous level, is a state in which only subtle psychological patterns remain: thoughts and ideas have temporarily ceased

Although Patañjali rather cryptically refers to the second level of yoga samādhi as anya (other), Vyāsa more explicitly calls it asa prajñāta. This state follows from the practice of the other (abhyāsa-pūrva

prajñāta. This state follows from the practice of the other (abhyāsa-pūrva ) and is akin to the nirbīja state where there is no external object of contemplation. It is an extremely rarefied state; because there is no external object, the consciousness of puru

) and is akin to the nirbīja state where there is no external object of contemplation. It is an extremely rarefied state; because there is no external object, the consciousness of puru a is only aware of itself. All other v

a is only aware of itself. All other v tti or activities of the mind have ceased and the mind is like a flawless jewel. Vyāsa states that it arises from extensive practice of sa

tti or activities of the mind have ceased and the mind is like a flawless jewel. Vyāsa states that it arises from extensive practice of sa prajñāta samādhi with increasingly subtle supports for our meditation (i.e., objects), accompanied by the highest levels of vairāgya.7 It is a state of pure being and is considered the pinnacle of the Yogic path.

prajñāta samādhi with increasingly subtle supports for our meditation (i.e., objects), accompanied by the highest levels of vairāgya.7 It is a state of pure being and is considered the pinnacle of the Yogic path.

Although it is of little practical relevance for the majority of us struggling with our practice in everyday life, it is nevertheless essential to be aware of asa prajñāta (or nirbīja) samādhi. Without an appreciation of the two levels of samādhi, it is easy to become confused about the teachings of the Yoga Sūtra and its commentaries, which discuss both levels. Nirbīja samādhi is something that may arise through advanced practice, but cannot be practiced in the ordinary sense of the word as it is not possible to simply “stop the activity of the mind” by an act of will. It's worth re-emphasizing—trying to “stop the mind” in meditation is one of the most unhelpful instructions that anyone can give! Our sādhana should be to direct, rather than to stop, the mind.

prajñāta (or nirbīja) samādhi. Without an appreciation of the two levels of samādhi, it is easy to become confused about the teachings of the Yoga Sūtra and its commentaries, which discuss both levels. Nirbīja samādhi is something that may arise through advanced practice, but cannot be practiced in the ordinary sense of the word as it is not possible to simply “stop the activity of the mind” by an act of will. It's worth re-emphasizing—trying to “stop the mind” in meditation is one of the most unhelpful instructions that anyone can give! Our sādhana should be to direct, rather than to stop, the mind.

Sādhana: Look, listen and feel—a bhāvana for sa yama

yama

Although it would be a mistake to think that we can progress neatly from dhāra ā to dhyāna and on to samādhi, it is possible to use bhāvana to deepen our involvement in a meditative practice at each of the different stages. Dhāra

ā to dhyāna and on to samādhi, it is possible to use bhāvana to deepen our involvement in a meditative practice at each of the different stages. Dhāra ā, dhyāna and samādhi can be equated with looking, listening and feeling, respectively. Like all bhāvana, this is a creative association where the bhāvana evoke something of the flavor of each step (somewhat poetically). In other words, don't take these ideas too literally . . .

ā, dhyāna and samādhi can be equated with looking, listening and feeling, respectively. Like all bhāvana, this is a creative association where the bhāvana evoke something of the flavor of each step (somewhat poetically). In other words, don't take these ideas too literally . . .

When we look at something specifically, such as a bird in a tree, we focus our eyes and watch it. We have an intention and we focus, but we are still separate. If we watch the bird intently for some time, there is a certain stability in our attention. “Looking” as a bhāvana here is not limited to our visual sense. It can be linked to all our senses and means of perception. It represents the intention “to look” in a particular direction, and to maintain the direction for some time (stability of link). It also suggests a sense of separateness (there is space between it and us). These evoke the characteristics of dhāra ā.

ā.

When we really listen, we are very attentive and receptive to what is being said. “Listening” emphasizes sensitivity and receptivity, once a direction of attention has been established. Whereas “looking” moves outwards from the subject to the object, the direction for “listening” seems just the reverse. As a bhāvana, “listening” is not restricted to our sense of hearing—an attitude beautifully summed up in the expression “listen to your heart.” This emphasizes a more sensitive and receptive state representative of dhyāna.

“Feeling” suggests a more immediate and sensitive contact with the object of enquiry such that it can be sensed directly. It emphasizes a direct perception with no separation, as if we have become the object of meditation. Whereas we may not see clearly, or we may mishear something being said, direct feeling suggests we know something as it really is. This more intimate relationship evokes one of the main qualities of samādhi.

Spend some time “looking” (with all your senses), then allow yourself to consciously “listen” and notice the difference in the quality of your involvement. Finally, let yourself “feel” the object of your focus as if you have become it and can sense it directly. Spending a few minutes with each of these steps in a meditation practice, or even for a number of breaths in an āsana or prā āyāma with a specific focus, can lead us progressively deeper into the experience. The process is a vinyāsa krama, and thus needs a completion stage, so it can be useful to add a fourth stage of “leaving” or “completing” where you consciously disconnect and return to a more usual sense of awareness.

āyāma with a specific focus, can lead us progressively deeper into the experience. The process is a vinyāsa krama, and thus needs a completion stage, so it can be useful to add a fourth stage of “leaving” or “completing” where you consciously disconnect and return to a more usual sense of awareness.