yoga sutra 2.18

prakāśa-kriyā-sthiti-śīla bhūta-indriya-ātmaka

bhūta-indriya-ātmaka bhoga-apavargārtha

bhoga-apavargārtha d

d śya

śya

Luminosity (prakāśa), activity (kriyā) and stability (sthiti) are the essential qualities (śīla) that make up the entire observable world (d śya). They are also the nature (ātmaka) of our own senses (indriya), and indeed of all of our bodies and the external world. Everything that exists is there to be experienced (bhoga)—and has the potential either to further enmesh us, or to set us free (apavarga)

śya). They are also the nature (ātmaka) of our own senses (indriya), and indeed of all of our bodies and the external world. Everything that exists is there to be experienced (bhoga)—and has the potential either to further enmesh us, or to set us free (apavarga)

This extremely important sūtra synthesises the heart of the philosophy of Sā khya and indeed of yoga. It explains the nature of the material world and describes how its characteristics run right through our subjective senses and the objective world that we perceive. It also explains that the phenomenal world has two primary purposes, and that for most of us, there is an order to them.

khya and indeed of yoga. It explains the nature of the material world and describes how its characteristics run right through our subjective senses and the objective world that we perceive. It also explains that the phenomenal world has two primary purposes, and that for most of us, there is an order to them.

The material world is simply prak ti—everything of which we can be aware. It is made up of three strands: prakāśa (light), kriyā (movement) and sthiti (stability). These are clever synonyms for sattva, rajas and tamas. One of sattva's qualities is prakāśa, it is luminous. The very nature of rajas is kriyā, activity. And tamas can be understood as inertia, resistance and thus stability, sthiti. These three gu

ti—everything of which we can be aware. It is made up of three strands: prakāśa (light), kriyā (movement) and sthiti (stability). These are clever synonyms for sattva, rajas and tamas. One of sattva's qualities is prakāśa, it is luminous. The very nature of rajas is kriyā, activity. And tamas can be understood as inertia, resistance and thus stability, sthiti. These three gu a permeate our senses (called indriya in the Yoga Sūtra), and our minds, and also the very elements (bhūta) which we perceive in the external world (including our physical bodies). Interestingly, and crucially, our senses, our minds and the world which we perceive are described as d

a permeate our senses (called indriya in the Yoga Sūtra), and our minds, and also the very elements (bhūta) which we perceive in the external world (including our physical bodies). Interestingly, and crucially, our senses, our minds and the world which we perceive are described as d śya—“seen.” Our senses and minds can be “seen” because we can step back and be aware of their operation. Perhaps they are dull, perhaps acute—but we can observe how they change and thus they are included as part of prak

śya—“seen.” Our senses and minds can be “seen” because we can step back and be aware of their operation. Perhaps they are dull, perhaps acute—but we can observe how they change and thus they are included as part of prak ti, the objective world of phenomena.

ti, the objective world of phenomena.

Finally, this sūtra ends with an extremely arresting statement: that the purpose (artha) of this world of phenomena is twofold. It is there for us to experience (bhoga), and then to transcend (apavarga). In other words, experiences are the very means to liberation and freedom. This liberation is called apavarga. It's worth noting that not all bhoga leads us to apavarga—indeed much bhoga will take us in exactly the wrong direction! What is important here is that only through skillfully lived experience does emancipation arise.1

It is utterly extraordinary that we are alive. According to one Buddhist parable, the chances of being born a human are similar to a turtle who swims up from the depths of the ocean once in a thousand years, putting its head through a single ring floating on the surface of the water. A man produces billions of sperm during his lifetime; just think how incredible it is that of all those, only one yoked with one of your mother's (many thousands of) eggs and . . . became you. It's worth reminding ourselves just how unlikely—and how precious—our existence truly is.

The ancient Indian philosophers also emphasized that being born into the human realm is a particular blessing because we are born with just the right amount of insight. Being born into the realms of animals means existing “as animals”: living primarily by instinct and without spiritual insight. In this realm, the primary drives are food, pleasure, avoidance of danger and so on, and this level is dominated by rajas and tamas. (It could easily be argued that some people live only in this realm). At the other end of the spectrum is living in the realms of the Gods, the so-called devaloka. According to mythology, this is dominated by sattva; it is a place of beauty and enjoyment and clarity. But—and it's an important “but”—there is too little suffering to make us want to explore the true nature of things; we are too cozy. Only in the human realm is there sufficient clarity and suffering: we are in the “Goldilocks orbit”—neither so far away that we have no insight nor so comfortable that there is no need to resolve our confusions and difficulties.

a

aIntuitively, we distinguish between inside and outside with our skin—everything internal to the skin is “us” and everything external is “other.” But as we have seen, yoga demarcates this boundary in another way: what is “internal” is the witness (puru a) and everything else is “external”—it is the “witnessed.” What we normally think of as internal to our bodies (our lungs expanding, our heartbeat, our muscles working) can be observed and, from the point of view of yoga, is actually external. It forms part of d

a) and everything else is “external”—it is the “witnessed.” What we normally think of as internal to our bodies (our lungs expanding, our heartbeat, our muscles working) can be observed and, from the point of view of yoga, is actually external. It forms part of d śya, the Seen.

śya, the Seen.

How do we understand that which is “internal”? Yoga suggests that by contrast to prak ti,2 there is an essence which does not change: this is called puru

ti,2 there is an essence which does not change: this is called puru a. Puru

a. Puru a is very difficult to talk about, however, because by naming it, we describe it, and thereby turn it into “a thing.” We give it qualities, form and substance: we treat it as prak

a is very difficult to talk about, however, because by naming it, we describe it, and thereby turn it into “a thing.” We give it qualities, form and substance: we treat it as prak ti. Yet puru

ti. Yet puru a has no form, no place, no time. It is the subject, rather than the object, of investigation. Rather poetically, Peter Hersnack once described puru

a has no form, no place, no time. It is the subject, rather than the object, of investigation. Rather poetically, Peter Hersnack once described puru a as “always the same, but always fresh.”3

a as “always the same, but always fresh.”3

The boundary between “inside” and “outside” is thus not the skin, but the distinction between puru a and prak

a and prak ti—terms for which Patañjali uses many synonyms throughout the Yoga Sūtra. This is as much a problem of language as one of perception: without clothing “it”4 in words, we would have no way of talking about puru

ti—terms for which Patañjali uses many synonyms throughout the Yoga Sūtra. This is as much a problem of language as one of perception: without clothing “it”4 in words, we would have no way of talking about puru a. Patañjali's numerous terms help to give us various perspectives on puru

a. Patañjali's numerous terms help to give us various perspectives on puru a:

a:

—the Seer (YS 1.3, 2.17, 2.20 and 4.23)

—the Seer (YS 1.3, 2.17, 2.20 and 4.23) a—person, the dweller in the city (YS 1.16, 1.24, 3.35, 3.49, 3.55, 4.18 and 4.34)

a—person, the dweller in the city (YS 1.16, 1.24, 3.35, 3.49, 3.55, 4.18 and 4.34)Each of these terms gives us a slightly different angle on the concept of puru a. It is awareness (cit) that receives information and content from our minds in the form of memories, the imagination or information from our senses. However, this awareness is separate from, and fundamentally untouched by, that content. Similarly, it is the Seer (dra

a. It is awareness (cit) that receives information and content from our minds in the form of memories, the imagination or information from our senses. However, this awareness is separate from, and fundamentally untouched by, that content. Similarly, it is the Seer (dra

) who receives all sensory information—and not just visual, but all the smells, tastes, feelings and sounds from the external world. If we lose a limb, of course we will feel differently about who we are to an extent, but we may lose limbs, have organs transplanted, hips replaced and still feel, in some ways, like “ourselves.” The ātman—sometimes translated as the “soul”—refers to that which remains when all the changing forms that constitute our identity have been taken away. In the Yoga Sūtra, this essence is construed as having no qualities. Finally, we could conceive of the body/mind complex rather like a city or a palace (pura) whose “inhabitant” is puru

) who receives all sensory information—and not just visual, but all the smells, tastes, feelings and sounds from the external world. If we lose a limb, of course we will feel differently about who we are to an extent, but we may lose limbs, have organs transplanted, hips replaced and still feel, in some ways, like “ourselves.” The ātman—sometimes translated as the “soul”—refers to that which remains when all the changing forms that constitute our identity have been taken away. In the Yoga Sūtra, this essence is construed as having no qualities. Finally, we could conceive of the body/mind complex rather like a city or a palace (pura) whose “inhabitant” is puru a—the dweller in the city.

a—the dweller in the city.

One simple and practical way to get something of the flavor of puru a's presence is to borrow a concept from Vedānta5 philosophy: that of sat (being), cit (awareness) and ānanda (bliss). In Vedānta, the very ground of being, the basis of all, is called Brahman and its qualities are described as sat-cit-ānanda. With this as our touchstone, we can intuit the presence of puru

a's presence is to borrow a concept from Vedānta5 philosophy: that of sat (being), cit (awareness) and ānanda (bliss). In Vedānta, the very ground of being, the basis of all, is called Brahman and its qualities are described as sat-cit-ānanda. With this as our touchstone, we can intuit the presence of puru a. At the end of a practice, sitting or standing quietly, ask yourself: Is there presence (sat)? Is there awareness and sensitivity (cit)? Is there joy, bliss (ānanda)? These can be taken as the signs, the markings, of the presence of puru

a. At the end of a practice, sitting or standing quietly, ask yourself: Is there presence (sat)? Is there awareness and sensitivity (cit)? Is there joy, bliss (ānanda)? These can be taken as the signs, the markings, of the presence of puru a.

a.

Although we have taken the liberty of discussing the various ways Patañjali has given form to puru a, we must always remember that, ultimately, puru

a, we must always remember that, ultimately, puru a is nirgu

a is nirgu a (without qualities), while prak

a (without qualities), while prak ti is sagu

ti is sagu a (with qualities).

a (with qualities).

ti and Gu

ti and Gu a

aThe classical Indian tradition understands prak ti (or d

ti (or d śya, the observable world) to be comprised of three fundamental forces: the three gu

śya, the observable world) to be comprised of three fundamental forces: the three gu a—sattva, rajas and tamas.

a—sattva, rajas and tamas.

It includes our bodies, and even our minds, thoughts, memories, feelings and emotions. Our thoughts and feelings are simply “stuff”—they are more subtle (less stable and tangible) than our legs and arms, but all “stuff” is subject to change—it grows, moves and decays. Stuff is subject to gu a. It has qualities and is therefore describable. It gets recycled and remolded into other stuff; thoughts evolve into other thoughts and even into physical realities (a thought can mold an expression or a posture); likewise, the material of our bodies is recycled into other bodies. Yoga makes no distinction between mind and body—both are simply aspects of prak

a. It has qualities and is therefore describable. It gets recycled and remolded into other stuff; thoughts evolve into other thoughts and even into physical realities (a thought can mold an expression or a posture); likewise, the material of our bodies is recycled into other bodies. Yoga makes no distinction between mind and body—both are simply aspects of prak ti. There is nothing stable or eternal about our identities or our thoughts; these will change just as the cells of our bodies will be replaced. As we have seen, all of this can, in some sense, be thought of as “external,” because it can be observed.

ti. There is nothing stable or eternal about our identities or our thoughts; these will change just as the cells of our bodies will be replaced. As we have seen, all of this can, in some sense, be thought of as “external,” because it can be observed.

It is worth taking time to really understand the three gu a because they lie at the heart of traditional Indian philosophy. There are a number of common misunderstandings in the contemporary yoga world about the gu

a because they lie at the heart of traditional Indian philosophy. There are a number of common misunderstandings in the contemporary yoga world about the gu a and their relationships with each other. Many people talk of trying to “balance” the gu

a and their relationships with each other. Many people talk of trying to “balance” the gu a, as if they could all come into a sort of equilibrium and stay there. Often people see tamas and rajas as undesirable, not understanding that their presence is essential and that they both have positive roles to play in the dance of life. Exploring how the gu

a, as if they could all come into a sort of equilibrium and stay there. Often people see tamas and rajas as undesirable, not understanding that their presence is essential and that they both have positive roles to play in the dance of life. Exploring how the gu a are presented in the Sā

a are presented in the Sā khya Kārikā (SK) gives us great insight into their meaning and use in the Yoga Sūtra. In SK 12 and 13, their purpose, their interactions with one another, and their essential characteristics are explained with masterly brevity and precision.

khya Kārikā (SK) gives us great insight into their meaning and use in the Yoga Sūtra. In SK 12 and 13, their purpose, their interactions with one another, and their essential characteristics are explained with masterly brevity and precision.

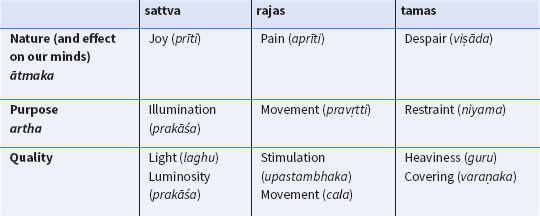

In SK 12, the effect of the three gu a on our minds is presented. The text states that the effect of sattva is joy (prīti), that of rajas is pain (aprīti), and finally tamas brings a feeling of despair (vi

a on our minds is presented. The text states that the effect of sattva is joy (prīti), that of rajas is pain (aprīti), and finally tamas brings a feeling of despair (vi āda). The joy of sattva does not necessarily mean an ecstatic, loud or external joy; it is more a peaceful beatitude, a feeling of being blessed. The experience of rajas is pain—wherever there is pain there is rajas. Rajas provokes movement, and there is nothing to make us move as quickly as the experience of pain. It stimulates. The effect of tamas is despair: a giving up and an impotent resignation. Tamas is there to block—it may block movement, feeling, understanding or initiative.

āda). The joy of sattva does not necessarily mean an ecstatic, loud or external joy; it is more a peaceful beatitude, a feeling of being blessed. The experience of rajas is pain—wherever there is pain there is rajas. Rajas provokes movement, and there is nothing to make us move as quickly as the experience of pain. It stimulates. The effect of tamas is despair: a giving up and an impotent resignation. Tamas is there to block—it may block movement, feeling, understanding or initiative.

Although, put like this, the effects of rajas and tamas seem undesirable, they serve an important purpose. SK 12 goes on to explain that while sattva is there to bring illumination (prakāśa), rajas brings movement (prav tti) and tamas restraint (niyama). None of these are inherently good or bad: they simply are. Without the movement of rajas or the restraint of tamas there would be no time, no growth and no boundaries. Once the dance of the gu

tti) and tamas restraint (niyama). None of these are inherently good or bad: they simply are. Without the movement of rajas or the restraint of tamas there would be no time, no growth and no boundaries. Once the dance of the gu a has started, it is really impossible to bring them into balance, because they are in constant dynamic relationship with one another, and their presence and interactions bring forth the world of form.

a has started, it is really impossible to bring them into balance, because they are in constant dynamic relationship with one another, and their presence and interactions bring forth the world of form.

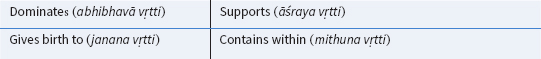

SK 12 describes their interactions with one another in four ways; we can further subdivide this into two pairs. In the first, one gu a dominates (abhibhava v

a dominates (abhibhava v tti), and another supports (āśraya v

tti), and another supports (āśraya v tti). There will always be a dominant gu

tti). There will always be a dominant gu a in any situation, but how that dominant gu

a in any situation, but how that dominant gu a manifests will be dependent on how it is supported. For example, when rajas is dominant there is movement. If it is supported by sattva that movement will be clear, precise and in an intelligent direction; if it is supported by tamas, the movement will be unclear, misdirected or lacking conviction or purpose.

a manifests will be dependent on how it is supported. For example, when rajas is dominant there is movement. If it is supported by sattva that movement will be clear, precise and in an intelligent direction; if it is supported by tamas, the movement will be unclear, misdirected or lacking conviction or purpose.

The second pair of interactions describe how the gu a give birth to one another (janana v

a give birth to one another (janana v tti) and also contain the seed of the others within them (mithuna v

tti) and also contain the seed of the others within them (mithuna v tti). There is always a cycle of change. When a fruit is growing towards ripeness, we could say the predominant gu

tti). There is always a cycle of change. When a fruit is growing towards ripeness, we could say the predominant gu a is rajas: it is moving towards wholeness. It has a sour taste and is sharp—both primary qualities of rajas. But within the predominant rajas are the seeds of the other two gu

a is rajas: it is moving towards wholeness. It has a sour taste and is sharp—both primary qualities of rajas. But within the predominant rajas are the seeds of the other two gu a and as the fruit ripens, rajas gives birth to sattva. However, the dance of the gu

a and as the fruit ripens, rajas gives birth to sattva. However, the dance of the gu a does not stop here and before long, sattva itself gives birth to tamas as the ripe fruit begins to decay. Although this pattern of growth (rajas) leading to maturity (sattva) and then to decay (tamas) is common (and this applies to civilizations and yoga lineages as well as fruit!), it is not the only way the dance can play itself out. Sometimes rajas can lead directly to tamas with no intermediate step of sattva. Janana implies there is a constant change from one gu

a does not stop here and before long, sattva itself gives birth to tamas as the ripe fruit begins to decay. Although this pattern of growth (rajas) leading to maturity (sattva) and then to decay (tamas) is common (and this applies to civilizations and yoga lineages as well as fruit!), it is not the only way the dance can play itself out. Sometimes rajas can lead directly to tamas with no intermediate step of sattva. Janana implies there is a constant change from one gu a to another; mithuna implies that all three gu

a to another; mithuna implies that all three gu a are always present at some level.

a are always present at some level.

Finally, in SK 13, each gu a is given two adjectives to describe its essential characteristic: sattva is said to be light (laghu) and luminous (prakāśa); rajas is stimulating (upastambhaka) and moving (cala); and tamas is heavy (guru) and obscuring, concealing or covering (vara

a is given two adjectives to describe its essential characteristic: sattva is said to be light (laghu) and luminous (prakāśa); rajas is stimulating (upastambhaka) and moving (cala); and tamas is heavy (guru) and obscuring, concealing or covering (vara aka). This is shown in the chart on page 129.

aka). This is shown in the chart on page 129.

a

a

ti

tiAs we have seen, at the highest level, Patañjali and Sā khya propose a duality: the twin poles of puru

khya propose a duality: the twin poles of puru a and prak

a and prak ti. One has form (prak

ti. One has form (prak ti) and one does not (puru

ti) and one does not (puru a); one is conscious (puru

a); one is conscious (puru a) and one is not (prak

a) and one is not (prak ti); one changes (prak

ti); one changes (prak ti), the other does not (puru

ti), the other does not (puru a). Some of these polarities are described in YS 2.5.6

a). Some of these polarities are described in YS 2.5.6

If we focus solely on prak ti, we will see how this is further divided into three. Three is very important—it is the minimum number to allow for a complex dance to arise. Each gu

ti, we will see how this is further divided into three. Three is very important—it is the minimum number to allow for a complex dance to arise. Each gu a has a unique aspect which stands in contrast to the other two, and yet each is also similar to the others in different ways.

a has a unique aspect which stands in contrast to the other two, and yet each is also similar to the others in different ways.

Rajas and tamas are sometimes described as do a7 of the mind—they “color” our perceptions (rajas with passion, symbolized by red, and tamas with delusion, symbolized by black). Too much rajas and tamas is therefore undesirable because our minds are adversely affected. When rajas is excessive there is no stability, and when tamas is excessive there is no clarity. By way of contrast, sattva cannot be excessive, because it is pure and illuminating, and therefore cannot color or stain.

a7 of the mind—they “color” our perceptions (rajas with passion, symbolized by red, and tamas with delusion, symbolized by black). Too much rajas and tamas is therefore undesirable because our minds are adversely affected. When rajas is excessive there is no stability, and when tamas is excessive there is no clarity. By way of contrast, sattva cannot be excessive, because it is pure and illuminating, and therefore cannot color or stain.

Rajas and sattva are by their very nature light and easily moved, whereas tamas is heavy. Tamas is able to provide boundaries and restraints; it gives structure, shape and form. Of course, this is essential and often helpful, but matter in the wrong place becomes “dirt” that obscures or weighs us down, blocking our perception or our movement.

Sattva and tamas are essentially inert; they do not move. It is only through the energy of rajas that sattva can grow or tamas can be moved and redirected. Rajas is the driving force which keeps the dance of prak ti in motion. It can move us towards our goal, or it can move us away from it.

ti in motion. It can move us towards our goal, or it can move us away from it.

It is very important to understand that gu a are not adjectives which describe aspects of prak

a are not adjectives which describe aspects of prak ti, or attributes of prak

ti, or attributes of prak ti: they are prak

ti: they are prak ti. Very pleasingly, the word prak

ti. Very pleasingly, the word prak ti is comprised of parts of the synonyms for the gu

ti is comprised of parts of the synonyms for the gu a: pra (from prakāśa), k

a: pra (from prakāśa), k (from kriyā) and ti (from sthiti) and the word itself thereby functions as a mnemonic to remind us that the gu

(from kriyā) and ti (from sthiti) and the word itself thereby functions as a mnemonic to remind us that the gu a are the fundamental ingredients of prak

a are the fundamental ingredients of prak ti.

ti.

Yoga has no concept of “spiritual transformation” or “spiritual growth”—because spirit (puru a) needs neither to transform nor to grow. In fact, it cannot—because it is unchanging. It is only prak

a) needs neither to transform nor to grow. In fact, it cannot—because it is unchanging. It is only prak ti that we need to restructure and the project of yoga can therefore be seen simply as gu

ti that we need to restructure and the project of yoga can therefore be seen simply as gu a recalibration. The cultivation of sattva in the mind is a recurrent theme that runs throughout the Yoga Sūtra; indeed, the very highest stages of yoga are expressed by Patañjali in terms of the prevalence of sattva in the mind.

a recalibration. The cultivation of sattva in the mind is a recurrent theme that runs throughout the Yoga Sūtra; indeed, the very highest stages of yoga are expressed by Patañjali in terms of the prevalence of sattva in the mind.

For any project to be successful, there need to be solid foundations. Stability and “givens”—things (people, ideas, structures) that can be relied upon—are vital. These are our supports, whose function is to provide stability and structure. A support is something that we can rely upon to be unmoving when we lean on it; in order to “take support” we must give something of ourselves to the support and trust that it will not collapse. A chair gives us support, the earth gives us support, a trusted friend can give us support. Here, we are using the concept of support as a synonym for the positive aspect of tamas: it is stable. Cultivating stability—finding and taking support—is the prerequisite to all growth. This works at all levels, from simple movements in āsana to the great journeys towards enlightenment. The first step is to “prepare the ground”—and only then can we use the inertia and stability of tamas as a springboard.

Direction is a challenge. Sometimes it is clear, sometimes we are confused and paralyzed by indecision: which path should we take? We have already seen (in Chapter 6) how in the Bhagavad Gītā, Arjuna was initially unable to act, caught between wanting to do the right thing and not wanting to engage at all. A direction requires a starting point and a goal. This may be a short-term goal or a long-term aspiration, but in order to get there, we must take intelligent steps in the right direction. In this sense, direction is part of vinyāsa krama. Because direction implies movement, we can also see it as an aspect of rajas. When direction is scattered, rajas is a do a (in the sense of being a fault); when our direction is clear and takes us towards our goal, we are using rajas appropriately because it is supported by sattva.

a (in the sense of being a fault); when our direction is clear and takes us towards our goal, we are using rajas appropriately because it is supported by sattva.

In Chapter 4, we discussed the concept of du kha. Du

kha. Du kha is the starting point; it is the discomfort, irritation, restriction that causes us to seek change. Whether it is intense or just a background niggle, the presence of du

kha is the starting point; it is the discomfort, irritation, restriction that causes us to seek change. Whether it is intense or just a background niggle, the presence of du kha is a reminder that our lives can change for the better. This does not necessarily mean a change in our external circumstances; sometimes (indeed often) it is a change of heart and mind. While du

kha is a reminder that our lives can change for the better. This does not necessarily mean a change in our external circumstances; sometimes (indeed often) it is a change of heart and mind. While du kha is largely associated with restriction, its opposite, sukha, is experienced as openness. A clear space opens up. Although sattva is generally equated with light, we can also link it with a feeling of spaciousness. A lit candle dispels the darkness and thus gives us space to see.

kha is largely associated with restriction, its opposite, sukha, is experienced as openness. A clear space opens up. Although sattva is generally equated with light, we can also link it with a feeling of spaciousness. A lit candle dispels the darkness and thus gives us space to see.

Desikachar once described the process of meditation as “when sattva uses the stability of tamas to give direction to rajas to create more sattva.”8 We can see how this formulation can be directly superimposed onto Patañjali's very definition of the yoga project: citta v tti nirodha. The true nature of citta is sattva, but when rajas and tamas dominate, citta is out of balance. When citta is in its natural state, it is permeated with sattva, and it can use the stability of tamas (nirodha) to direct the movement of rajas (v

tti nirodha. The true nature of citta is sattva, but when rajas and tamas dominate, citta is out of balance. When citta is in its natural state, it is permeated with sattva, and it can use the stability of tamas (nirodha) to direct the movement of rajas (v tti). One could almost see it as a mathematical equation:

tti). One could almost see it as a mathematical equation:

citta v tti nirodha (CVN) = sattva rajas tamas (SRT).

tti nirodha (CVN) = sattva rajas tamas (SRT).

This formula can be expanded out to embrace the whole yoga project. Yoga's starting point is the feeling of du kha. Through yoga, we aim to open something within us to move towards sukha, a more spacious experience of the world. However, that movement needs to be carefully and skillfully crafted—experiencing “states” is relatively easy, but turning states into traits takes time, commitment and practice. It requires a reorientation of our habitual tendencies. The path from du

kha. Through yoga, we aim to open something within us to move towards sukha, a more spacious experience of the world. However, that movement needs to be carefully and skillfully crafted—experiencing “states” is relatively easy, but turning states into traits takes time, commitment and practice. It requires a reorientation of our habitual tendencies. The path from du kha to sukha needs support: it needs to be held, cherished, preserved and protected. This requires boundaries. Once the boundaries are established there can be movement in a suitable direction; the boundaries are there to protect the practice and to lessen the tendencies towards dissipation (too much rajas) or inertia (too much tamas). When we see clearly, we see what we need to restrain and how we can move. The more space (sattva) there is, the more beneficial the workings of support (tamas) and direction (rajas), resulting in yet more space.

kha to sukha needs support: it needs to be held, cherished, preserved and protected. This requires boundaries. Once the boundaries are established there can be movement in a suitable direction; the boundaries are there to protect the practice and to lessen the tendencies towards dissipation (too much rajas) or inertia (too much tamas). When we see clearly, we see what we need to restrain and how we can move. The more space (sattva) there is, the more beneficial the workings of support (tamas) and direction (rajas), resulting in yet more space.

We use the support (nirodha) of tamas to give direction (v tti) to rajas, to open more space for sattva (citta).

tti) to rajas, to open more space for sattva (citta).

This simple formula can apply to āsana, prā āyāma, meditation, chanting, devotional practices, food—even our relationships with our teachers or indeed the Tradition itself. It is at the very heart of our understanding of the journey of yoga.

āyāma, meditation, chanting, devotional practices, food—even our relationships with our teachers or indeed the Tradition itself. It is at the very heart of our understanding of the journey of yoga.

Is the cultivation of sattva and the consequent feeling of spaciousness enough? It is certainly the prerequisite; flooding our being with sattva is the aim of the practices described by Patañjali in his famous eight limbs of yoga (a

ā

ā ga). But the danger of stopping here, according to both yoga and Sa

ga). But the danger of stopping here, according to both yoga and Sa khya, is, as we have seen, that we get stuck in the realms of the Gods and forget our journey. We become too comfortable. Moreover, the gu

khya, is, as we have seen, that we get stuck in the realms of the Gods and forget our journey. We become too comfortable. Moreover, the gu a dance will continue; just because we are in a space of sattva today doesn't mean that tamas and rajas won't dominate tomorrow as we are caught up again in the whirligig of gu

a dance will continue; just because we are in a space of sattva today doesn't mean that tamas and rajas won't dominate tomorrow as we are caught up again in the whirligig of gu a fluctuation.

a fluctuation.

YS 2.18 finishes with two possible directions which our experiences can take us towards: bhoga or apavarga. Bhoga means “enjoyment”—not necessarily in the sense of pleasure, but meaning that we enjoy the fruits of our karma: we get what we get. Bhoga is experience to be experienced; it is food to be digested. It is only through ingesting that we grow. We need experiences in order to realize our place in the world and to help us be our best possible selves. But equally, experience has the potential to corrupt: too much, too soon, or inappropriate experiences which remain unprocessed can act like poison, leaving us with “mental indigestion” that results in bitterness, fear or resentment. It is a fine line to walk, but the practice of yoga and the cultivation of sattva can be a huge help in maintaining our stability and navigating the potentially difficult experiences that we have to face throughout our lives. So, the first step is to deal most elegantly with our experiences, to creatively and skillfully engage with bhoga.

But Patañjali offers another step, which is not just about dealing with bhoga but about transcending it altogether: apavarga, meaning “liberation” or “emancipation.” Any experience, any aspect of nature, can be used as a means of transcendence. When we have experienced something sufficiently to know that we don't need to repeat it, we have understood that particular lesson, digested and outgrown it, then we have achieved (to some degree) liberation. This step necessitates vairāgya, the ability to remain free within certain situations; to minimise unhelpful and automatic reactions (usually involving desire or aversion). Even sattva has a pull, a gravitational weight to it, and for Patañjali the ultimate goal is to be completely free within the dance of prak ti, irrespective of whether sattva, rajas or tamas dominates. Our center has moved sufficiently from the fortress of our constructed self to allow a far more transparent mode of Being where we are no longer impelled to act out our habits and compulsions.

ti, irrespective of whether sattva, rajas or tamas dominates. Our center has moved sufficiently from the fortress of our constructed self to allow a far more transparent mode of Being where we are no longer impelled to act out our habits and compulsions.

The word order here is very important; bhoga comes before apavarga.9 We need experience to digest; only then can we transcend. We cannot say that we are “above something” if we have never tried it or experienced it. Experience requires us to engage, process and then to move on, and it is our responses that determine whether we are further embroiled or moving towards liberation. Desikachar puts it simply: “The World exists to set us free.”10 Responding with vairāgya is the movement from bhoga to apavarga.

Sādhana: Dynamic and static āsana

One of the most important supports that we have when we come to practice āsana is the depth of the tradition. We can refer back to our teachers, and also to the wealth of literature that has enriched our understandings and our practice. We know that Patañjali has defined yoga as citta v tti nirodha (YS 1.2, see Chapter 1), but Desikachar has given us a very simple and structured vinyāsa which takes us towards this goal. “Without āsana practice, prā

tti nirodha (YS 1.2, see Chapter 1), but Desikachar has given us a very simple and structured vinyāsa which takes us towards this goal. “Without āsana practice, prā āyāma cannot be mastered. Without prā

āyāma cannot be mastered. Without prā a nirodha, mind will not become stable.”11 Thus, we need āsana to contain the body (kāya nirodha), then prā

a nirodha, mind will not become stable.”11 Thus, we need āsana to contain the body (kāya nirodha), then prā āyāma to contain the breath (prā

āyāma to contain the breath (prā a nirodha), and finally we contain the mind (citta v

a nirodha), and finally we contain the mind (citta v tti nirodha). He ordered the progression in this way because we start with the grossest, most tangible and therefore the easiest to manipulate (the body), and finish with the most subtle (the mind).

tti nirodha). He ordered the progression in this way because we start with the grossest, most tangible and therefore the easiest to manipulate (the body), and finish with the most subtle (the mind).

What does it mean to “contain the body”? To us, this means holding the body (relatively) still for a reasonable length of time in order to embody the qualities of sthira and sukha in a static posture.12 This requires strength, stability and flexibility. To obtain these qualities, it is very useful to work with the breath, and to work with dynamic postures first as a preparation for static āsana. Looking at ancient texts like the Ha ha Yoga Pradīpikā, there is scant information on vinyāsa krama. For example, this is how it describes the lotus posture (padmāsana, fig 7.1):

ha Yoga Pradīpikā, there is scant information on vinyāsa krama. For example, this is how it describes the lotus posture (padmāsana, fig 7.1):

“Place the right foot on the left thigh and the left (foot) on the right thigh, cross the hands behind the back and firmly take the toes (the right toe with the right hand and the left toe with the left). Place the chin on the breast and look at the tip of the nose. This is called padmāsana; it destroys all diseases . . .” HYP 1.46. 13

And this is how the symmetrical seated forward bend (paścimatānāsana, fig 7.2) is described:

“Stretch out both legs on the ground without bending them, and having thus taken hold of the toes of the feet with the hands, place the forehead upon the knees and rest thus. This is paścimatānāsana.” HYP 1.28.

Apart from the minimal detail on the route in and out, the texts are often very scant on how long one should stay in postures, or the order of postures and so on. In the ancient Sanskrit texts, there is little emphasis on dynamic āsana; postures are described as positions to stay in (often for a very long time) in order to cultivate meditative absorption. However, this emphasis on static āsana highlights the dangers of taking ancient texts too literally, especially if you don't have a teacher to help deconstruct them and make their teachings digestible and practical. For most people, straining to stay in something like the lotus posture in the hope of gaining immortality is simply delusional and will not engender sthira and sukha: it will simply damage the knees!

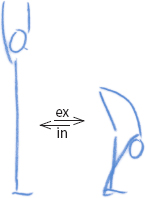

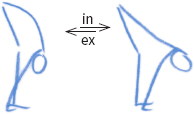

Krishnamacharya was very precise in his teaching about dynamic āsana. In the modern Western world, the term “dynamic” is sometimes equated with “strong” or “intense”; but this is not the meaning we intend here. We understand the term dynamic to simply mean “moving”—practicing a posture dynamically means moving in and out of the form. What is the function of dynamic āsana, and why did Krishnamacharya stress its importance?

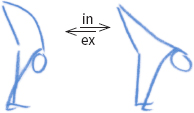

Dynamic postures involve large movements of the body. Moving completely in and out of the posture is a full-range movement (fig 7.3); we can also have mid-range movements (partial movements in and out of the posture, fig 7.4) and even micro-movements (subtle movements made while maintaining the posture, fig 7.5). These movements help to warm and train the body (and attention) to move slowly and carefully into and out of the pose. In other words, working dynamically prepares the body to stay in the pose. Mid-range and micro-movements can follow full-range movements of the body as we refine and intensify our practice:

There is another good reason to use dynamic posture work as preparation for static. If you are traveling at 50 mph in a car and then suddenly slam on the brakes, the contents of the car will continue to move although the car has stopped. Similarly, sitting still after you've been rushing around with a busy mind can sometimes actually amplify your perception of the busy mind. If instead you change down through the gears as you move from 50 mph to a standstill, the contents will slow at the same rate as the vehicle and by the time the vehicle comes to rest, so too does the driver. Dynamic work not only prepares the body physically, but also gives the attention a support; instead of the mind being dissipated it can focus on the movement. By giving the mind something tangible to hold on to, the mind is being harnessed and directed. So, at a psychological level too, dynamic work is also a good preparation for static work.

Finally, it is worth comparing our ability to breathe in a static āsana with our breath in a dynamic one. Most people will find their breath far more compromised when staying in a posture than when moving in and out. This is because if we work intelligently with the breath, synchronizing it with appropriate movements of our limbs and torso, the breath will actually support the movements of the body and the movements will support the breath.14 For example, a movement into a forward bend will compress the abdomen and push the diaphragm upwards into the thoracic cavity facilitating an exhalation. Similarly a movement into backward bend lifts the ribcage and expands the chest, facilitating an inhalation. It is the movement into and out of the postures that facilitates the breath; once you're in the posture, retaining the same slow deep breath is often more challenging. Once again, we have a compelling reason to start working dynamically prior to static āsana.