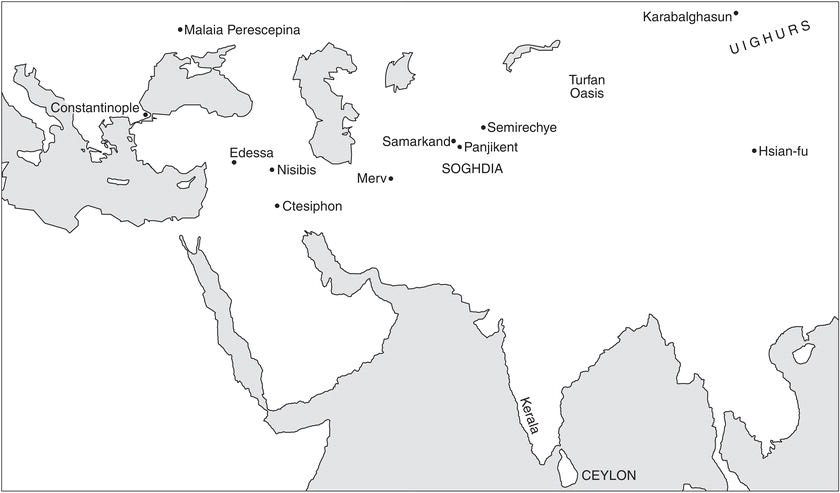

Map 5 The Middle East, from Constantinople to Iran

In 591, a party of Turks from eastern Central Asia arrived at Constantinople. They bore the sign of the Cross on their foreheads.

They declared that they had been assigned this by their mothers; for when a fierce plague was endemic among them, some Christians advised them that the foreheads of their young be tattooed with that sign.1

These Turks had come from what is now Kirgizstan, some 2,300 miles east of Constantinople, close to the borders of modern China. They had learned about the sign of the Cross from the Christian communities which were established along the entire length of the Silk Route, which led from Antioch, through Persia, to China.

Christians of the East Roman empire of the sixth century knew that they lived in a wide world. Thirteen days of travel to the east of Antioch took them to the frontier of the Persian empire, to Nisibis (Nusaybin, eastern Turkey), the first city in Persian territory. Then the distances seemed to stretch endlessly, into furthest Asia. Eighty days of travel east of Nisibis took the traveller beyond Persia into Central Asia, to the great oasis cities of Merv and Samarkand. A further 150 days were required to reach Hsian-fu, the western capital of China.

Map 5 The Middle East, from Constantinople to Iran

Map 6 Christianity in Asia

| THE MIDDLE EAST ca. 450–ca. 800 | |

| Yazdkart II, King of Kings 439–457 | |

| Battle of Avarayr 451 | |

| P’awstos Buzanderan | |

| writes Epic Histories 470 | |

| Barsauma, bishop of Nisibis 470–496 | |

| Khusro I Anoshirwan, King of Kings 530–579 | |

| Cosmas Indicopleustes | |

| writes Christian Topography ca.550 | |

| Khusro II, King of Kings 590–628 | |

| Heraclius, emperor 610–641 | |

| defeats Khusro II 627 | |

| Muhammad 570–632 | |

| begins to receive Qur’ân 610 | |

| flight from Mecca to Medina 622 | |

| Battle of Yarmuk 636 | |

| Battle of Qâdisiyya 637 | |

| Eastern Christians at Hsian-fu 638 | |

| Calif Mu’awiya 661–680 | |

| Ummayad Califate 661–750 | |

| Calif ʿAbd al-Malik 685–705 | |

| builds Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem 691/2 | |

| Conquest of Spain 711 | |

| Defeat of Muslims at Constantinople 717 | |

| Battle of Poitiers 733 | |

| Calif Hisham 724–743 | |

| Abbasids replace Ummayad califate 750 | |

| Foundation of Baghdad 762 | |

| Calif Harûn al-Rashid 786–809 | |

We know these distances from the writings of a pious merchant from Antioch (known to us by the colorful but misleading name of Cosmas “Indicopleustes” – Cosmas the India-Sailor).2 Cosmas had traded down the Red Sea to Axum and Socotra. He knew, through the accounts of fellow-merchants, of communities of Christians from Persia settled along the Coromandel Coast and in Ceylon. These colonies of Christian merchants from the Persian Gulf were the originators of the modern “Saint Thomas’ Christians” of Kerala.

Cosmas’ Christian Topography (written in around 550) was an optimistic tract. For him, the earth was reassuringly flat. Heaven stretched above it like a vast dome. There were no Antipodes, as pagan philosophers vainly imagined. No unknown races lurked at the other side of a round earth. Cosmas felt that he could survey the entire world. And in the immense territories of Asia, Christianity appeared to be the dominant religion. It was already the religion of one world empire, the empire of the Romans, and it was widespread in the Persian empire also.

Cosmas was fortified in these views by a sense of divine providence. Because it was the empire in which Christ had been born, the Roman empire was destined to last forever. He applied to it the prophecy of the Book of Daniel: The God of Heaven shall set up a kingdom which shall never be destroyed (Daniel 7:14).

The empire of the Romans thus participates in the dignity of the kingdom of Christ, seeing that it transcends as far as can be … any other power and will remain unconquered until the end of time.3

Cosmas found room for the Persian empire, also, in the divine scheme of things. This was a frankly pagan empire, associated in Christian minds with the Persian Magi, the grave pagan priests from whom our word “magic” is derived. Zoroastrianism was the religion of the “Magi.” It was the state religion of the Persian empire. The second greatest power in the world, and the neighbor of the Christian empire, had remained as staunchly pagan as the Roman empire had been in the days of the emperor Diocletian. But this did not worry Cosmas. For the Magi had come to Bethlehem to pay homage to Christ when he was born. The Three Wise Men of the Gospel account were regarded, by eastern Christians of this time, as Persian ambassadors. By coming all the way to Bethlehem, they had come to recognize the supreme lordship of Christ, as the King of Kings. In Christian mosaics of the time – such as that in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna – the Wise Men are shown approaching Christ, as he is carried on the lap of the Virgin Mary, who is seated on an imperial throne. They wear the exotic trousers and Phrygian caps with which Persian ambassadors were shown, on imperial monuments, when they brought tribute to the Roman emperor.

As regards the empire of the Magi … it ranks next to that of the Romans, because the Magi, in virtue of their having come to offer homage and adoration to the Lord Christ, obtained a certain distinction.4

In the generations which followed the death of Justinian, it did, indeed, seem as if Asia had become a smaller place. The terrible incursion of the plague, in 542–3, had been a reminder that the East Roman empire lay at the western end of a commercial system which included all of Asia and the Indian Ocean. The Silk Route also became more active, as the Chinese empire expanded westward, making its presence felt deep into Inner Asia, as far as the Tarim Depression and the great oasis of Turfan. After 550, embassies from Po-tzu, from Persia, were a regular occurrence at the court of the Chinese emperor at Hsian-fu. Even Antioch and Syria were described, for the first time, in Chinese gazetteers of the “Western Lands.”5 Small Christian communities, adapting differently to different environments along the way, were part of a steady trickle of information, merchandise, and displaced persons which took place along the entire length of the Silk Route, from Antioch to China. We should not underestimate the “conductivity” of such a route. News travelled quickly along it. A monk writing in the monastery of Qenneshre, on the banks of the Euphrates, mentioned a total eclipse (in the year 627), which could have been observed only in western China!6

The “shrinking” of Asia at this time was in part the result of renewed conflict in the Near East. In Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine, the Christian populations were divided between two world empires. Those in the west (in what is now modern eastern Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, and Israel) were subjects of the Christian empire of East Rome and those to the east (in an area which coincides roughly with modern Iraq) belonged to the pagan, Zoroastrian empire of Sasanian Persia. These two empires were spoken of as “the two eyes of the world.”7 For almost 70 out of the 90 years between 540 to 630, they were at war. From the Caucasus to Yemen in the south of Arabia, and from the steppelands of the Euphrates to eastern Central Asia the two superpowers maneuvered incessantly to outflank each other. As a result, the inhabitants of the Near East found themselves caught between “two powerful kingdoms who roared like lions, and the sound of their roaring filled the whole world with thunder.”8

The warfare between East Rome and Persia was highly professional and murderous in its impact. Nothing like it occurred in western Europe. At a time when Justinian’s armies in Italy were seldom larger than 5,000, armies of up to 50,000 men clashed in the plains and foothills of northern Mesopotamia. Brigades of heavily armored Persian cavalry rode in tens of thousands across the plains and steppelands of Syria. Ancient cities endured sieges, capture, and the deportation of their entire populations: this happened to Antioch in 540 and to Apamea in 573. In terms of cost, bloodshed, and human suffering, the “barbarian invasions” of western Europe were no more than minor dislocations compared with such campaigns. This was the real face of war.9

Yet, just because it was highly professional warfare, waged by strong states, its impact, although atrocious, was limited. The 70 years of warfare between East Rome and Persia eventually led to the exhaustion of the two states which conducted it. But it did not lead to a total destabilization of society and to a breakdown of law and order. Paradoxically, indeed, the societies over which the armies of Rome and Persia fought remained wealthy and self-confident in a manner which contrasted, in an increasingly ominous manner, with the bankruptcy of the states who were supposed to defend them.

From Antioch eastward to Edessa and south to Gaza, the cities of the Christian empire remained the centers of government. But they no longer bore an entirely classical face. Their temples were closed. The traditional agora which marked the center of public space was replaced by the courtyards of great Christian cathedrals. In many cities, the ancient, grid-like streets of the Hellenistic age were cluttered with artisan shops and bazaars. Open spaces gave way to more enclosed and inward-looking forms of housing. The cities of the age of Justinian and his successors were alive; but they were alive now with a different spirit. They were less dedicated to self-consciously “classical” ideals of public space and of the comfort and entertainment of their citizens. Theaters and public baths gave way to markets and to untidy agglomerations of inward-looking, deeply private houses.10

And, in any case (as we saw in chapter 7) the countryside had levelled up with the cities. The sixth century was the heyday of the Christian village. In modern Syria, Jordan, Palestine, and Israel, the boom of village life continued past the years of the plague. If anything, after the plague, districts in the hinterland throve at the expense of the Mediterranean cities. In Jordan, for instance, village life reached ever further into the hinterland, up to the very edge of the Arabian desert. The Beduin of the steppes, and not the Mediterranean, provided the villagers with a new market.

Many of these were large villages, as populous as any city. In the village of Rihab (modern Jordan) nine churches were built between 533 and 635. Made up of houses consisting of closely linked, enclosed courtyards, these villages presented a closed face to the outside world. The only public buildings in them were the churches. Villages such as these often supported monasteries, many of which were centers of teaching and learning in their own right, as creative as any urban school. It was in this distinctive environment of great villages and their adjacent monasteries that the Monophysite “dissidence” throve and defied the efforts of Justinian and his successors to bring them back to the state Church.11

Most paradoxical of all, the generals and the troops who fought across these Near Eastern landscapes were usually foreigners to the region. The armies of the “Romans” were largely recruited in Asia Minor and the Balkans; those of the Persians came from the closed world of the Iranian plateau and from the steppes of Central Asia. To enter Syria from Constantinople was to descend from the Anatolian plateau into a different world. To descend from Iran into Mesopotamia was also to find oneself among foreigners. Both empires fought to control a Syriac-speaking “heartland” whose language they did not understand. As for the inhabitants of the region – the political and military frontier between the two empires meant little to them. Syriac-speaking Christian villages stretched on both sides of the frontier, without a break, from the Mediterranean to the foothills of the Zagros. It was possible to travel from Ctesiphon, the Persian capital in southern Mesopotamia, to Antioch, speaking Syriac all the way.

Despite the ravages of war, the sixth-century Near East was crisscrossed by travelling clergymen and intellectuals for whom the political frontier between Rome and Persia was irrelevant. Culturally and religiously, Syria and northern Mesopotamia were a vortex. It was a region where ideas and forms of piety and culture met, were transformed, and spread westward to the entire Mediterranean and eastward as far as western China. In Italy, Cassiodorus (whom we met in chapter 8) modelled his cultural program, in part, on what he had heard of the great Christian Academy founded by Syriac-speakers at Nisibis, on the Persian side of the frontier. He was amazed to hear of such a large school, in which Christian biblical exegesis was taught in public, much as the classics had been taught in Rome. On the Roman side of the frontier, at Reshʾaina (near Tel Halaf in modern Syria), Sergius, a priest and physician, made a Syriac commentary on the Organon of Aristotle in the 530s. Sergius had no doubts as to the importance of his enterprise:

Without these [Aristotle’s logical works] neither can the meaning of medical writings be attained, nor can the opinions of philosophers be understood, nor, indeed, can the true sense of the divine Scriptures be uncovered … For education and advancement in the direction of the sciences … cannot take place without the exercise of logic.12

He had made the work of Aristotle available for his fellow-Syrians in Syriac. Working in Rome, as we saw in chapter 8, Boethius had done the same, by translating Greek texts into Latin. But the work of Sergius was soon carried across distances of which Boethius, in Rome, could not have dreamed. Within a few years, the Syriac guide to Aristotle was in the hands of Sergius’ colleague, a Syriac-speaking bishop of Merv, a great oasis city on the northeastern frontier of Persia, some 1,200 miles to the east of Syria, in what is now Uzbekistan.

Syrians felt that they stood at the crossroads of Asia. They knew that they saw more widely than did the proud Greeks who formed the core of the eastern “Roman” empire. To take one example: a later translator, Severus of Sebokht (d.666/7), refers to the system of “Indian” numbers. This system was quickly adopted by the Arabs. Hence, the numerals we use today are called “Arabic numerals.” They are considerably easier to use than are the clumsy numbering systems of the Romans and the Greeks. Severus instantly appreciated the importance of this Indian invention:

Had they been aware of these, the Greeks, who imagine that they alone have reached the summit of wisdom just because they speak Greek, would perhaps have been persuaded … that there are other people who have some knowledge!13

Culturally and socially, the political frontier between East Rome and Persia meant little. The true frontiers of the sixth- and seventh-century Near East were ecological. The plains of Palestine, Syria, and Mesopotamia formed a “heartland” of Syriac-speaking populations, most of whom were Christians. But these plains were surrounded, as in a mighty arena, by foothills leading up to high mountains. To the west lay the Taurus mountains and the high plateau of Anatolia; to the north, the Hakkari mountains and, behind them, the Caucasus; to the east, the Zagros mountains stretched southward from the Caucasus to the Persian Gulf, cutting off the high, dry plateau of modern Iran from the rich, alluvial plains of Mesopotamia.14

Everything in this world depended on the presence of rain. In northern Mesopotamia, the foothills of the high mountain systems received ample snow and rain. They were rich in fruit trees, grain, olives, and wine. They were dotted with great monasteries. A mountain range between Edessa and Nisibis, still known as the Tur ‘Abdin, “the Mountain of the Servants of God,” had over 80 monasteries. Many of these have survived as Christian monasteries up to this day. They are masterpieces of stonework, and notable for their immense water-cisterns.15

Only in northern Mesopotamia, at the foot of the mountains, was rain-based, “dry” agriculture possible. Southern Mesopotamia, in Persian territory, depended entirely on a carefully maintained system of irrigation, leading from the Tigris, the Diyala, and the Euphrates. What is known as the Fertile Crescent linked Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean. This belt of settled land was largely made up of Christian villages. To its north lay mountains and rain; but to the south lay a gigantic wedge of arid steppeland, which was the northernmost reach of the great Arabian desert. Here, under 200 millimeters of rain fell every year. One had to travel south over 1,500 miles of wasteland, among tribesmen who spoke only Arabic, before reaching green again on the edge of the Indian Ocean. In the southwest corner of the Arabian peninsula, the mountain settlements of the Yemen (watered by the same rains from Africa as caused the yearly flooding of the Nile) were covered with miraculous green. Here a sophisticated, Arabian society throve, supported by systems of water catchment and by irrigation from great dams.16 Five hundred miles to the west, across the southern end of the Red Sea, the well-watered mountains of the Christian kingdom of Axum (the future empire of Ethiopia) completed the great oval of watered and unwatered lands which made up the sixth-century Near East.

Each of these regions was affected, and each differently, by the confrontation between Persia and East Rome. Let us begin in the mountains of the north. The ambivalence of a frontier area was made particularly plain in the case of Armenia. The high mountain valleys which stretched between Mesopotamia and the Caucasus were a reservoir of military manpower. Like the Swiss Landesknechten or the Scottish Highlanders of later times, Armenians were prominent in the armies of both empires. They came from a culture which relished heroes. A seventh-century arithmetic exercise for Armenian schoolboys went as follows:

I heard from my father that, in the times when Armenians were fighting the Persians, Zarwen Kamsarakan performed memorable feats of prowess. Attacking the Persian army, he killed half on the first attack … a quarter on the second … and an eleventh on the third. Only 280 Persians survived. How large was the Persian force before he laid them low?17

Armenia looked both east and west. In its social structure and lay culture it was a westward extension of the feudal society of Persia. Yet it was not a Zoroastrian country. Christianity had entered the mountains of Armenia from the Syriac-speaking plains around Edessa and from the river valleys which led up from Greek-speaking Caesarea in Cappadocia to Karin/Theodosiopolis, which is now Erzerum in eastern Turkey. Under king Trdat III (298–330) and his adviser Grigor, “Gregory the Illuminator,” Armenia became a nominally Christian kingdom. This happened in around 314, at the same time, that is, as the fateful conversion of Constantine in the Roman empire. Armenia did not survive for long as an independent kingdom. In 387, it was divided between Rome and Persia.18

But what did survive, across the new political frontier, was a common Christianity. Armenians on both sides of the frontier belonged to the same Armenian Church, under a single Armenian Katholikos. The unity was sealed by the flowering of a newly created Christian culture. The Armenian alphabet was created around 400 by Mesrop Mashtots (who died in 439). While Coptic and Syriac had been the final adaptation, to Christian purposes, of millennial literate cultures, the clerical elites of Armenia moved, within 50 years, from an oral culture into literacy. As a result, Armenian historiography echoed directly the preliterate world of the epic minstrels. Accounts of Christian saints and kings were structured around notions of power and heroism which belonged to the feudal world of the Iranian plateau. This was a literature with a strong substratum of Iranian oral epic. Nothing like it existed in the Christian Near East, or, indeed, anywhere in Europe, until the flowering of Old Irish, at the other end of the Christian world, in the seventh and eighth centuries.19

Not all Armenian clergymen approved of the social milieu which produced such heroic tales. Despite triumphal narratives which looked back to the formation, in Armenia, of the first non-Roman Christian kingdom, in the heroic age of Trdat and Saint Grigor, the conversion of the warrior aristocracy of Armenia had been a slow process. In the disabused words of P’awstos Buzand (Faustus the Bard, who wrote around 470):

[The Armenians] did not receive Christianity with understanding … but as some purely human fashion, and under duress … Only those who were to some degree acquainted with [book] learning were able to obtain some partial inkling of it. As for the rest … they cherished their songs, their legends and epics, believed deeply in them and persevered in their old ways, in their blood-feuds and enmities.20

If these proud warriors related to the Church at all, it was in the manner of the warrior elites of the barbarian west. They approached the Church much as the aristocrats of northern Francia approached the monasteries of Columbanus. They came as princely donors. They were careful to make offerings “for the forgiveness of their sins.” But they had little intention of amending their own pre-Christian ways. One Katholikos (described disapprovingly by P’awstos) saw this only too clearly:

[The Katholikos Yohan would] go down on all fours, braying with the voice of a camel … “I am a camel, I am a camel, I bear the sins of the king; put the sins of the king upon me” … And the kings wrote and sealed deeds for villages and estates and put them on Yohan’s back in exchange for their sins.21

P’awstos’ realistic estimate of his fellow-countrymen was not popular with his ecclesiastical colleagues. Armenian Christianity required heroic foundation myths if it was to survive at all. This was provided by an epic encounter between the Christian aristocracy of eastern Armenia and their overlord, the Persian King of Kings. At the famous battle of Avarayr, in 451, a faction of the nobility, led by Vardan Mamikonian, died fighting against the Persian army of the King of Kings, Yazdkart II (439–457).

Yazdkart had attempted to impose Zoroastrianism on their country. But the Christian nobles did not fight the representatives of Yazdkart so as to become independent of the Persian empire. They fought so as to remain faithful vassals of the King of Kings, even though they were Christians. They regarded it as unjust that they should be expected to become Zoroastrians. They wanted to retain their honor and their standard of living as the marcher-lords of the Persian empire, whose secular mores (religion apart) were so like their own.22

The brilliant narratives of Lazar of Pharp, in around 500, and of Elishe Vardapet, Elishe the Teacher, ensured that the 1,036 Armenian warriors who fell at Avarayr would be remembered forever after as Christian martyrs. Vardan and his companions were presented as the heirs of the Jewish Maccabees. Like the Maccabees, they were faced by a formidable empire. Their ranks were thinned by the apostasy of many of their fellow-noblemen to Zoroastrianism. Yet Vardan and his army died to preserve the “traditions of their fathers.” Their loyalty to Christianity took the form of a solemn “Covenant,” sworn upon a copy of the Gospels. It was a Covenant which embraced nobleman and peasant alike. On both sides of the frontier between Roman lands and Persia, all Armenians were henceforth expected to be loyal to a single “patrimonial faith.”23

Furthermore, the “patrimonial faith” of Armenia took on a form of Christianity which made Armenians different from the despised Syrians of the lowlands of Persian Mesopotamia. The Armenians opted for Monophysitism. By so doing, they made the Armenian Church independent of the staunchly anti-Monophysite “Church of the East,” the Church of the Syrian Christians of Mesopotamia, which was the principal representative of Christianity in the Persian empire.24

In all of this, Armenian writers presented their heroes as avatars of a militant Israel. In Armenia, the Old Testament and the warlike history of the People of Israel were put to use in the present in a manner which was similar to the appeal to Old Testament models made by clerical writers in the warrior kingdoms of the west.25

To the south of the warlike highlands of Armenia, in the Syriac-speaking lowlands, it was not a heroic battle but an ecclesiastical event which determined the future identity of the various Christian communities of the region. The Council of Chalcedon also happened in 451. We have already followed (in chapters 4 and 7) the repercussions in the Eastern empire of the failure of the greatest imperial council of all times. By the middle of the sixth century, a Monophysite “dissident” Church had become established throughout the eastern provinces of the Roman empire. A tentacular network of counter-bishoprics, monasteries, and village priests and holy men of anti-Chalcedonian views stretched from Egypt, Nubia, and Axum across the Fertile Crescent, entering the territories of the Persian empire as if no frontier stood in its way. Based on an unusual combination of theological sophistication and intense, Christ-centered piety, Monophysitism, in its various forms, was the dominant, and certainly the most vocal, faith of the western Syriac world.

The “Church of the East,” however, rose to the challenge. This was the Church of the Christian communities in Persia, the “Empire of the East.” This Church is often called “the Nestorian Church,” and the Christians of Persia, “Nestorian Christians.” Like many ecclesiastical labels forged in a time of controversy, it is a “lamentable misnomer.”26 The leaders of the Church in Persia were conservatives. They deeply disapproved of the radical Christology of the Monophysites. They believed that God had graciously revealed himself fully to the human race through a chosen human being, Jesus Christ. But God had not blurred his identity with that of Christ. He had not suffered with Christ on the Cross, as the Monophysites appeared to say. In the opinion of the Church of the East, this was a terrible doctrine. It ascribed suffering and loss to God himself. They thought that the Council of Chalcedon had not gone nearly far enough in opposing the blasphemous absurdity – that God could suffer like a human being – which seemed to be sweeping the Syrian world of the west. The bishops assembled at Chalcedon had failed to do their job:

Owing to their feeble phraseology, wrapped in an obscure meaning … they found themselves standing at a cross-roads and they wavered.27

In taking such a view, the “Church of the East” was loyal to its roots. Until the very end of the fifth century, the Christian communities in the Persian empire had been an eastward extension of the religious culture of the church of Antioch. The great Antiochene exegete, Theodore of Mopsuestia (350–428), had created the intellectual climate which produced Nestorius. He was revered by his admirers throughout Syria and Persia as “the Universal (that is, the World-class) Exegete.” No Persian Christian wished to disown the seemingly bottomless wisdom of Theodore, a past master of scriptural exegesis.

We saw in chapter 4 how the extreme views of Nestorius had led to the crisis which provoked the Council of Ephesus of 431 and the Council of Chalcedon in 451. But, compared with Theodore, Nestorius was little known in the “Church of the East” before Syriac translations of his works appeared in the middle of the sixth century. Rather, it was the hard-line Monophysites, bitter enemies of Nestorius, who used the term “Nestorian” as a slogan of abuse.

After Chalcedon, Monophysites came to predominate in Edessa. Edessa was the sister city of Nisibis. It was the first major city on the route from Nisibis, on the Persian side of the frontier, toward the west. As a result of the “takeover” by Monophysite radicals at Edessa, boundaries hardened. For the first time in the history of Syriac-speaking Christianity, it became increasingly difficult to come to study at Edessa from Nisibis, only a few days’ travel across what up to then had been a largely dormant frontier. In 489, the school for students from Persia in Edessa was closed. At the same time, the churches in Persia rallied, explicitly, to anti-Monophysite doctrines, thereby founding what has been known, ever since, to Western scholars (largely on the strength of Monophysite polemics), as the “Nestorian” Church.28

From 470 to 496, Barsauma was the bishop of Nisibis. A high-handed man, Barsauma was accused by later Monophysite writers of having deliberately pushed the “Church of the East” into accepting the heresy of Nestorius in order to seal the frontier between Rome and Persia. The two empires would now have different, and mutually hostile, forms of Christianity within their frontiers. But the split between the “Church of the East” and its western neighbors was the result of a far longer development. The Christians within the Persian empire had begun to feel at home. They no longer looked westward, toward the Roman empire.29

In the fourth century, most Christians in Persia had been “Roman” foreigners. They were descended from the thousands of Syrians who had been brought back from Syria to Mesopotamia as captives by Shapur I in the 260s. But times had changed. Christians now came from the Iranian population itself, either through intermarriage or, occasionally, through conversion. Pehlevi (middle Persian) joined Syriac as the other language of the Church of the East. It was Persian Christians, and not only Syriac-speakers from northern Mesopotamia, who penetrated the markets of Asia. A sixth-century eastern Christian cross – a distinctive, quasi-cosmic symbol, half a Cross and half an ancient Mesopotamian Tree of Life – has been discovered as far east as Travancore, with a Pehlevi inscription.30 Pehlevi, also, would have been the language of the successful Christian entrepreneurs who controlled the pearl fisheries of the Persian Gulf. Their bishops needed to warn them to allow their divers to rest on Sundays. Christian Rogation ceremonies took place, along the shore, to clear the waters of giant sharks. Such persons did not think of themselves as “Romans” manqués, but as Persians who happened to be Christians.31

The emergence of a silent majority of Persian Christians in the hinterland coincided with a dramatic transfer of Syriac high culture to the Persian side of the frontier in Mesopotamia itself. Nisibis became one of the great university centers of the Near East.32 Students from all over Mesopotamia flocked to Nisibis, the new “Mother of Wisdom.” In its methods of teaching, the school of Nisibis may have resembled the schools established in the large Jewish villages of southern Mesopotamia. Unmarried young men, distinguished by a semi-monastic style of life and dress, settled in the cell-like rooms of a former caravansary. They would memorize the Psalms, the New Testament, and passages from the Old Testament, along with the works of Theodore of Mopsuestia. The intensive work of memorization formed the basis, also, of the intricate chants and specially composed hymns which were the glory of the eastern Christian, as of every other Syriac, liturgy. Headed by a teacher such as Narsai (around 480–90), who wrote over 300 religious Odes, the school of Nisibis was to be a training-ground for religious poets as well as for exegetes.

In the culture of the Syriac-speaking world, holy books were supposed to saturate the heart. They did so by being translated into melodious sound, carried by the magical sweetness of the human voice. Unlike the Vivarium of Cassiodorus, this was no hushed world, in which the written text alone spoke to the reader, as a solitary, silent instructor. By contrast, the Syriac world, in east and west alike, was filled with sound. Hence the importance of the qeryana, the “reading aloud” of the Scriptures. Through the qeryana, the Syriac language was raised to a new pitch. It became a tongue rendered sacred through the repeated, exquisite recitation of the Word of God. Exegesis itself was not a purely intellectual probing of the text of the Scriptures. It was a reliving of the Scriptures through recitation combined with a reverential “robing” of the Word of God, in the form of explanations and amplifications of the biblical text, in a manner which closely resembled the Midrashic techniques of the rabbis. In a Syrian church, the “reading” held the center of attention:

Now there was present … a great learned priest who had gone out to the porch of the church to meditate upon the outline of his sermon, which he wished to deliver in a learned manner … But when the deacon, Mar Jacob, had begun to recite the Psalm, the sweetness of his voice so greatly attracted the attention and mind of everyone … that the learned priest cried out with a loud voice: “Fie on you, young man, for the sweetness of your voice has … driven out of my mind the thoughts which I had wished to gather together!”33

Carried in this way, on the voices of young men, a culture based upon reading aloud the message of God in the church was particularly well suited to the task of “internal mission” which maintained a remarkable degree of cultural and religious unity among the Christians of the East, whose churches stretched from Mesopotamia to China. A large Christian cemetery discovered at Semirechye, in eastern Kazakhstan, shows that Christian communities survived up to the time of the Mongol empire in the thirteenth century. The gravestones show how this could be so. Eight hundred years after the founding of the school of Nisibis, and over three months of travel from Mesopotamia, the “Church of the East” had maintained a quite distinctive style of transmission for their religious culture. The tombs were inscribed in a bold Syriac script which had changed little over the centuries:

The year 1627 [that is, from the foundation of Antioch by king Seleucus! – A.D. 1316] … in the Year of the Dragon, according to the Turks. This is the grave of Sliha, the famous Exegete and Preacher … son of the Exegete Petros. Praised for his wisdom, his voice was raised like a trumpet.34

The expansion of the “Church of the East” was due to the sheer size and strategic position of the Persian empire. The Persian territories of Mesopotamia were no more than the western fringe of a political system which reached as far as the middle of Asia. The rulers of this empire were aggressively Zoroastrian. Yet their strong rule indirectly fostered the spread of Christianity throughout an officially pagan empire. The Sasanians (to call the rulers of the Persian empire by their local name, from the dynasty to which they belonged) tamed the fragile flood-plains of the Tigris and the Euphrates. In some regions, they almost doubled the area of settlement and maintained levels of irrigation unequalled before modern times. As a result, their empire was hungry for manpower. Khusro I Anoshirwan, “of the Immortal Soul” (530–579), and Khusro II Aparwez, “the Victorious” (591–628), renewed the policy of Shapur I. Their wars against East Rome were slave-raids on a colossal scale. Thousands of Christian captives were settled in new towns and villages both in Mesopotamia and along the fertile but precarious oases which edged Central Asia. From Mesopotamia, Christians gained a foothold on the plateau of Iran, the traditional heartland of Persia, and from Central Asia the roads lay open as far as China.35

For the Christian communities within his empire, the King of Kings was a formidable but studiously distant presence. The pressures toward religious conformity which were so strong in East Rome and in the Christian kingdoms of the West did not weigh as heavily upon the subjects of the Sasanian empire. The occasional aristocrat who converted to Christianity was subjected to gruesome public execution, as a renegade from Zoroastrianism. Zoroastrianism was known as the beh den, “the Good Religion.” It was considered to be too good a religion to be wasted on non-Persians. It was, indeed, a compliment to the Armenians on the part of Yazdkart II that he thought them capable of sharing the “Good Religion” of true Iranians. Syrians were not expected to join this very exclusive club. Usually, as long as subject religious groups were loyal and paid their tribute, they were not greatly troubled. Unlike the Christians of East Rome, who shared in the euphoric myth of an eternal Roman empire, blessed by Christ and inhabited (apart from the Jews) by Christians only, the Christians of the East learned to live among non-Christians, under a non-Christian state. It was a lesson which would prove invaluable to them in succeeding centuries.36

Christians emerged at the court of Khusro II as privileged royal servants, somewhat like the “King’s Jews” of medieval Europe. Shirin, his principal wife, was a devout Christian. Yazdin of Kerkuk (in northern Iraq) was Khusro’s all-powerful financial minister. Yazdin was acclaimed as “the Constantine and the Theodosius” of the Church of the East.

When the armies of Khusro II broke the defenses of Syria, after 610, these high-ranking Christians joined with gusto in the spoliation of their “heretical” East Roman neighbors. When Jerusalem fell to the Persians, in 618, the relic of the True Cross made its way to Mesopotamia. It was intended for the royal palace at Dastkart. Dastkart was set, appropriately enough, within sight of the ruins of ancient Nineveh, from which the Assyrians had struck at Jerusalem 12 centuries previously. But the True Cross ended up as the treasured property, not of the pagan King of Kings, but of the eastern Christian community of Yazdin’s Kerkuk.37

Moving with little difficulty in a pluralistic society, groups of eastern Christians fitted with ease into the vast horizons which opened up from Persian Central Asia. They joined other groups in the cosmopolitan oasis city of Merv, and soon settled, also, among the Turkish nomadic tribes who acted as the overlords of the trading cities of eastern Central Asia.

From there they established themselves east of the Oxus, along the foothills of the Hindu Kush and the Tien Shan mountains, in the autonomous cities of Soghdia. The Syriac copy of a Psalm, made by a Christian schoolboy, with which we opened our account of the spread of Christianity in the first chapter, was made at Panjikent, a major commercial center in Soghdia, near Samarkand in modern Uzbekistan.

The Soghdians were wide-ranging merchants. Known to the Chinese as men “with mouths full of honey, and gum [to catch every penny] on their fingers,” their journeys knit Asia together. Many became Christian. An eastern Christian cross with a Soghdian inscription has been found as far away as Ladakh, on the route to Tibet. Through the Soghdians, Christianity became a religion of the nomads who gravitated around the western frontiers of the Chinese empire.38 Syriac formed the basis of the script of the Uighur kingdom of southern Mongolia. Most surprising of all, the Mongolian word for “religious law,” used of Buddhism – nom – may be a distant echo, through Soghdian, of the Greek nomos, “law.” A central Greek concept was carried as a loan word in Syriac – namûsa – to the heart of Asia.39 In the course of four centuries, Bardaisan’s “Law of the Messiah,” with which we began our first chapter, had travelled a long way!

In the Turfan oasis of western Chinese Sinkiang, invaluable manuscripts of Manichaean scriptures were found. As we saw in chapter 3, Manichaeism was the perpetual Doppelgänger of Syrian Christianity. It also reached Inner Asia at this time, and would survive in China until the fourteenth century.40 In the nearby village of Bulayiq, a Christian church was found. Its library included a Soghdian translation of the Antirrheticus of Evagrius of Pontos (346–399). This was a work on the spiritual struggle of the monk, written in Egypt by a man who had been the friend and adviser of none other than Melania the Elder, the heroine of Paulinus of Nola, whose dramatic return to Italy from the Holy Land we described in chapter 3. Translated into Syriac, Evagrius had become the master of the art of contemplation in the Syrian world. Now an ascetic text of Evagrius was being read in Soghdian, in an unimaginably distant setting, close to Buddhist monasteries which housed its exact equivalent, a guide to ascetic living entitled The Sutra of the Causes and Effects of Actions, also in Soghdian translation.41

In 635, eastern Christians submitted a “Defense of Monotheism” to the Chinese emperor at Hsian-fu. Three years later (in the same year, indeed, as Jerusalem was lost to Muslim invaders), a Christian monastery was established in Hsian-fu and works of Syriac theology, derived ultimately from the fourth-century Antiochene culture of Theodore, the “Universal Exegete,” were formally placed, in Chinese translation, in the imperial library, among the many exotica of the distant western lands.42

As we have seen, the development of Christianity in both the Persian and the Roman regions of the Near East took place against the background of an escalating conflict between East Rome and Persia. Each of the two superpowers of western Asia had reached out, far into Inner Asia, to seek allies and commercial advantages in an effort to tip the balance in a struggle for total control of the Middle East. After 603, it was as if the keystone of an ancient arch had collapsed. The days of Xerxes or, alternately, the days of Alexander the Great had come again. First, the Roman empire seemed to collapse. Between 610 and 620, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria fell to Persian armies. Then, in 627, the emperor Heraclius (610–641) struck back into the heart of the overextended empire of Khusro II. In a brilliantly unconventional strategic move, he fell on Mesopotamia from the north, straight from the Caucasus. He led an army reinforced by nomadic cavalry drawn from the steppes around the Caspian Sea. He burned the palace of Khusro at Dastkart. He celebrated Christmas Day 627 in the great church at Kerkuk. Khusro II was murdered. The True Cross was returned in triumph to Jerusalem, accompanied by Heraclius himself – the first and last East Roman Christian emperor ever to set foot in the Holy Places.

Heraclius’ triumph took place against the background of a war-weary Middle East. The cities of the Fertile Crescent had been emptied by massive deportations. The olive groves around Antioch had been hacked to the ground in vindictive raids. Large areas of Mesopotamia were awash again, through neglect of the royal dams. More dangerous still, for the continued existence of the two existing empires, local leaders throughout Syria and Mesopotamia had learned, again and again, for over a generation, the necessary art of surrendering, with good grace, to foreign conquerors.43

In this long war, one area of the Near East had attracted little attention. It was taken for granted that the Arabs of the steppelands and the deep desert of Arabia were insignificant. Local Christians wrote of them with contempt:

There were many people between the Tigris and the Euphrates who lived in tents and were barbarous and murderous. They had many superstitions and were the most ignorant people on earth.44

It was assumed that such ignorant starvelings were easy to control. One wily Arab sheik advised another to play the part of the “desert Arab” when he visited the Persians.

Put on your travelling clothes, gird yourself with your sword, and when you sit down to eat, take big mouthfuls … eat much and appear hungry … for this pleases the king of Persia … For he thinks that there is no good in an Arab unless he is a hungry eater, especially when he sees something which is not his accustomed food. If he then asks, “Will you master your Arabs for me?”, say, “Yes.”45

And yet, in the course of the sixth century, the Arabian peninsula had been drawn into the religious and political confrontations which had swept the settled land. The Arabian peninsula became a gigantic echo-chamber, in which the conflicting political and religious options of the Near East were closely observed, and the weaknesses of the competing empires were sharply assessed. By ignoring the Arabs, the inhabitants of the settled land had been lulled by immemorial stereotypes into a false sense of security.

The total separation of the desert from the sown had been a myth purveyed for millennia by the governing classes of the empires of the Near East. Though frequently repeated up to this day, there was little truth in this myth. All along the steppelands which ringed the villages of Roman Syria and Persian Mesopotamia, Arabic-speaking tribesmen were partners in the economic life of the region. Food could not move without their camels. Marginal land would not remain fertile without the dung of their herds. The goods produced by the large villages would find no market if they did not pass, southward, into the lands of the Arabs. Like the Roman limes in Europe, the ecological frontier between the settled land, blessed with the gift of moisture, and the arid desert was not an absolute boundary. It was a middle ground. Along the western hinterland of Mesopotamia and the eastern edges of Syria and Palestine, in a wide belt which stretched from the outskirts of Antioch to the Gulf of Aqaba, settled populations and nomads found themselves drawn together, despite the differences in their languages and social structures, despite much mutual suspicion, and despite the veritable “cascade of contempt” which poured from high places upon the heads of the Arabs.46

In the first place, the increasing demands of war between the two empires rendered the Arabs indispensable. Arab sheiks controlled the vital routes across the steppelands which joined Roman Syria to Persian Mesopotamia. It was an Arab ally who led the army of Khusro I Anoshirwan straight to Antioch, across the steppe, in 540. The Arab tribes found themselves drawn into the confrontation between the two great powers. A wide defensive zone, in which the Arabs played a crucial role, developed along the borders of Syria and Persian Mesopotamia. It was if they were “trapped on a rock between two lions, Persia and East Rome.”47

Faced by this situation, the Arab leaders could always merge back into the desert. The arid steppeland was a place of refuge and a reservoir of tribal fighting men, feared for their swift raiding. But (like any other barbarian leaders along the Roman frontiers) they preferred to exploit their position so as to control the entire middle ground on both sides of the ecological divide between the desert and the sown. Sheiks of the Jafnid family of the Banu Ghassân were major landowners in Syria and patrons of the local Monophysite church. They left their mark on the landscape (much as the Frankish aristocracy left their mark on the fields of northern Gaul) by founding monasteries at permanent watering places where settled land and desert met. There they would set up their encampments and would set their herds of war-horses to graze on the rich grass. These monasteries were long remembered by Arab writers.

They built monasteries in pleasant places, abounding in trees, gardens and water-cisterns. Their [liturgical] plate was in gold and silver, the curtains in the churches of brocaded silk. They placed mosaics on the walls, and gold and images upon the ceilings.48

At Resafa (Rusâfa in modern Syria, west of the Euphrates, some 20 miles south of Raqqa) the Banu Ghassân controlled the greatest religious shrine in the Arab world.49 Resafa was also called Sergiopolis. It was the “city of Saint Sergius.” Sergius had been a Roman soldier who was executed as a Christian in the Great Persecution. At that time, Resafa was no more than a frontier fort, perched in an apparent wilderness. East Romans called it “the Barbarian Plain.” But the “Barbarian Plain” was no longer empty. Or, rather, those who lived in it were visible, for the first time, because they were Christians and they were useful. As Christians, the Arab tribes of the steppes met Syrian, Greek, and Persian Christians of the settled world in a common devotion to Saint Sergius. They would seek baptism there. Sergius, Sarjûn, or Sargis in Arabic, became a favored “Christian name” among the Arabs. Arab leaders availed themselves of the sacrality of the site. The leading sheik of the Banu-Ghassân, al-Mundhîr, may even have held the meetings where he presided as a tribal judge in a domed building where the relics of Sergius himself were kept, a short distance outside the walls of the sanctuary city.50 Christianity and leadership among the tribes went hand in hand along the Syrian frontier.

But this was the case also on the Persian side of the desert. The sheiks of the Banu Lakhm at Hira, on the Persian frontier, were also Christian. The court of the Banu Lakhm at Hira was a gathering place for some of the greatest Arab poets of the age. Hira was a “camp.” But, like Resafa, it was also a Christian holy city. It was the burial place of Katholikoi of the Church of the East and the scene of heated disputes between Nestorians and Monophysites.51

The message of these northern camps was quickly transmitted to the south. Religious confrontation was in the air. On the edge of the green mountains of Yemen, the oasis city of Najrân sheltered an oligarchy of Christian merchants who were as rich as any in Edessa or Alexandria. Najrân thought of itself as the Resafa of the south. In 523, the Arab clans of Najrân were brutally crushed by a Himyarite Arab king in Yemen, Dhû Nuwâs, who had opted for Judaism. By so doing, Dhû Nuwâs hoped to create, in the rich lands of southern Arabia, a “Davidic” kingship which was independent of the Christian powers.52 As we saw in chapter 5, Dhû Nuwâs was eventually defeated by the Axumite Christian, Ella Atsbeha, a warrior king as enterprising and as convinced that he had God on his side as was his contemporary in the distant northwest, Clovis, the king of the Franks.

But the Christian conquest of Yemen did not take place before the pros and cons of Christianity and Judaism had been hotly debated, in Arabic and in a manner which resounded throughout the Arab world. Far from the inhibitions imposed by dominant orthodoxies, the central issues of both faiths were open to fierce contention: was Christ divine or was he a mere human being? Was he greater than Moses or simply a crucified sorcerer? Altogether, had Christianity and the forms of Christian piety which had developed by the sixth century (monasticism and the cult of saints and relics in particular) been a great mistake? In the words of a former Christian bishop who had converted to Judaism:

In truth, if you were to meet the prophets of old, they would have spat in your face … for you have chosen corrupted ways which are false and aberrant.53

Such debates would have been unthinkable in the orthodox empire of Justinian. But they were perfectly normal in Arabia. For the historian, there is nothing remarkable about the fact that, around the year 600, Christianity and Judaism were well known throughout the Arabian peninsula. What is remarkable, rather, is that, in the person of Muhammad of Mecca (570–632), the Arabian peninsula produced a prophet who, in the opinion of his followers as of all later Muslims, had received from God authority to transmit, to his fellow-Arabs, God’s own, definitive judgment on both Christianity and Judaism.54

Muhammad grew up in Mecca, a city in the Hijâz, in the same years as Columbanus settled in Luxeuil and Gregory the Great lamented the ruins of Rome. Some 600 miles north of Najrân and a good 1,000 south of the frontier villages of the Roman empire, Mecca was an unprepossessing place. Untouched by rain, unlike Yemen, it was one of a number of settlements made possible by the existence of a spring of water. It maintained itself as best it could through trade with similar settlements, which were scattered all over the central and northern parts of the Arabian peninsula. Its inhabitants were “townsmen” only in the sense that they controlled a settled area.

The Arabian peninsula was not an empty space, crossed only by nomads. It had many settlements like Mecca. They were tiny ecological cracks in the austere, lava sheath of the Arabian desert. Their population outnumbered the true nomads. But they depended on these nomads for the circulation of goods on which each settlement depended. They shared with the “Arabs of the desert” a common deposit of social values. They were tribesmen. In the absence of a state, safety depended on membership of a clan which was prepared to defend its members, its livestock, and its wells against all comers. It made little difference whether one lived in a settlement or as an Arab of the desert: whichever way, the tribe was everything. The townsmen also shared in the constant shifting of a pan-Arabian pecking order. Some tribes were “strong” and “noble” and others were “weak” and easily pushed to one side. Above all, they shared the only form of stunning wealth which societies bereft of material goods tend to create with exuberant abandon: they spoke the richest language in the entire Near East. Arabic had already acquired a “classical” homogeneity, through the constant interchange of poets and storytellers. An Arabic script had been developed and was used for inscriptions in many parts of Arabia. This was a world where words carried. What was known and thought in distant Resafa, Hira, and Najrân was clearly heard in the oasis settlements of the Hijâz.55

It was once thought that the key to the emergence of Mecca at the time of Muhammad could be found in the fact that the Hijâz lay along great caravan routes, which carried the trade of Yemen and the Indian Ocean northward to the Mediterranean. There is little truth in this view.56 The “international trade” which mattered more, in the Arabia of Muhammad, was a trade in religious ideas, carried with remarkable “conductivity” from north to south. And this trade in ideas gained immensely in explosive content as it entered a tense world where tribe was always pitted against tribe and oasis against oasis. Some tribes of central Arabia had adopted Judaism. Others, such as the Banu Ghassân, were known for their Christianity. Religious differences were part of the ceaseless battle for prestige between the tribes. Faced by an open world, already polarized between Jews and Christians, Persians and East Romans, the dominant family of Mecca, the Quryash, were proud to remain frank idolaters. In a world where Jews and Christians, and even the great empires of the Near East, had come uncomfortably close, they thought it best to stand to one side and wait.

Not so Muhammad. In 610, when he was 40, the visions began to come. They came from the One God (in Arabic: Allah), “the Lord of the Worlds.” For the next 20 years, the messages came irregularly, in sudden, shattering moments, up to his death in 632. In them, so Muhammad believed, the same God who had spoken to Moses and to Jesus, and to many thousands of humbler prophets, now spoke again, once and for all, to himself. Vivid sequences of these words from God were carefully memorized by Muhammad’s followers. They were passed on by skilled reciters throughout the Arabic-speaking world. For these were nothing less than snatches of the voice of God himself speaking to the Arabs through Muhammad. They were not written down until after 660, in very different circumstances from the time of their first delivery. When written out, they came to form the single book known to us as the Qur’ân.57

Qur’ân and the Syriac qeryana come from the same root qr’, to read, to cry aloud. Both accorded the fullest measure of authority to a religious message when it was carried, directly, by the human voice. A once-skeptical Meccan was believed to have described his experience in listening to such a “reading.” Like the learned Syrian preacher who listened to the “reading” of Mar Jacob, he was shaken by what he heard:

I thought that it would be a good thing if I could listen to Muhammad … When I heard the Qur’ân [that he was reciting] my heart was softened and Islam entered into me. By God [said another], his speech is sweet.58

But for Muhammad’s followers, this was no Syriac religious ode, not even a Psalm of David, a human composition offered by man to God. What Muhammad recited was, rather, a direct rendering of the eloquence of God as he spoke to the human race. This God had never ceased, throughout the ages, to “call out” to all nations, through his many prophets. Now this voice repeated itself, in Arabic, in a final and majestically definitive summation.

It was this aspect of the Qur’ân which instantly offended Jews and Christians. For the messages relayed by God through Muhammad claimed to undo the past. His messages declared that neglect and partisan strife had caused Jews and Christians to slip away from, even to distort, the messages which they had once received from their prophets, Moses and Jesus. Christians were told, in no uncertain terms, that they had erred. They were warned by God that the Christological controversies which had absorbed their energies for so many centuries were based on a gigantic misunderstanding. Jesus had not been God and had never claimed to be treated as if he was God:

And behold [at the Last Judgment] God will say: “O Jesus, son of Mary! Didst thou say unto men: worship me and my mother as gods in derogation of God?” He will say: “Glory to Thee. Never could I have said what I had no right to say.” (Qur’ân v:119)

Though they played an essential role in defining the position of Muhammad’s later followers in a world of Jews and Christians, the messages directed against Judaism and Christianity were less central than was the message which Muhammad brought to the Arabs themselves. He was acutely conscious of having been sent by God to his fellow-countrymen to warn them, in clear Arabic, to change their pagan ways. They were to return to the original purity of an uncorrupted past. They were to realize that they were the descendants of Abraham, the father of Ishmael. The Ka’ba of Mecca (a local shrine erected around a meteorite) had been the spot where Abraham himself had sacrificed to the one, true God. Now the Quraysh had filled it with idols. In reclaiming the Ka’ba for his worship alone, Muhammad and his followers would regain for Mecca the powerful blessing of God.59 All who heard this message should surrender themselves to the will of God. For this was what all religious persons had done since the beginning of time.

The name adopted by the new religion, “Islâm,” and the word used to describe its adherents, “Muslims,” came from the same Arabic root, slm – to surrender, to trust in one God. It summed up an entire view of history. It was a history where, in what truly mattered for human beings – that is, their relationship to God – nothing had ever changed. Islam and Muslims had always existed. In all past ages, trust in God and the rejection of all other worship had invariably distinguished true monotheists from ignorant polytheists. God had fostered this monotheism by sending his prophets to the Jews and to the Christians. Those who accepted sincerely the messages of Moses and Jesus were Muslims without knowing it.60

Now the Arabs were summoned to partake in the same, perennial faith. And if they did not, they would be lost. The gaunt ruins of so many dead cities, which lay along the caravan routes of the Arabian peninsula, spoke to Muhammad of the swift approach of the Last Judgment quite as clearly as the ruins of Rome spoke to his older contemporary, pope Gregory. Both men, the Arabian prophet and the Roman pope, thought of themselves as sent by God to warn a world in its last days:

Do they not reflect in their own minds? Have they not travelled the land and seen what was the end of those before them? They were superior to them in strength: they tilled the soil and populated it in greater number than these have done. (Qur’ân xxx:19)

But how many countless generations before them have We destroyed? Canst thou find a single one of them now, or hear so much as a whisper? (Qur’ân xix:98)

If the Arabs listened to God’s warning, however, they might face a very different prospect:

Before, We wrote in the Psalms: … My servants, the righteous, shall inherit the earth. (Qur’ân xxi:105, citing Psalm 37:22)

A remarkable group of young men, caravan merchants and warriors, had been the Companions of Muhammad throughout his career. They had defended his cause with arms, in the authentic Arab manner. They had “striven hard,” risking their wealth, even their lives, to maintain his honor and safety: the word jihâd, usually translated as “holy war,” originally meant little more than to “strive” to keep one’s end up in a world which took tests of martial courage for granted. For young tribesmen, raiding the camels of one’s rivals and showing one’s prowess by making members of “weak” tribes back down was fun, and not particularly lethal fun. To fight the new Companions of Muhammad, however, was not fun. It was lethal, for the Companions fought in earnest. They did so in order to defend their religion. Very soon they struck out, to “humble” stubborn opponents. They cited as warrant for their deadly seriousness as warriors the behavior of the frontier troops of the East Roman empire. Those soldiers had been stationed on the edge of the desert by Christian emperors so as to protect churches and monasteries. They also fought so as to humble unbelievers. For inhabitants of the settled empires, there was nothing strange in the idea that warfare was blessed by God. But, within Arabia itself, the sheer aggression of the followers of Muhammad changed the rules of the game.61

In 622, Muhammad and his Companions emigrated to the more northerly oasis of Medina. This was a hijra – an emigration of a leader and his armed band to find a new place to settle. By this move, they had re-created themselves as a new tribe, a small nation in arms, like any other Arab tribe, but more determined. In all later centuries, Muslims would count the years from the date of the hijra to Medina. In 630, Muhammad and his Companions returned in triumph to Mecca. They purged the Ka’ba of its idols. Unlike the destruction of temples in the Christian empire, this was not acclaimed by Muslims as a victory over the ever-present demons. The purging of the Ka’ba was more like the restoration of a painting. A veneer of ignorant practices, piled up over the centuries, was scraped away to reveal the original, simple temple, uncluttered by idolatry, where Abraham had once worshipped the true God in Mecca.62

The year 630, which marked the return of Muhammad to Mecca, was the same year as the emperor Heraclius had brought the Holy Cross in triumph back to Jerusalem. It was a moment of high emotion. Heraclius was believed to have dismounted and walked the last 200 miles to the Holy City on foot, like a rejoicing pilgrim.63 Only two years later, 1,200 miles to the south, Muhammad died, in 632. Muhammad’s Companions survived the death of their leader. Having gained respect throughout Arabia by forming a confederation of towns joined together by a common acceptance of Islam, they were able to offer their allies conquests of which they had not dared to dream.

This was not surprising. To seventh-century persons, it was not particularly shocking. The Companions of Muhammad were blunt men in a society inured to war. They were as convinced as the emperors Justinian and Heraclius had been that God blessed the armies of those who trusted in him. They intended to use their armies to inherit the earth. As an Armenian writer reported it:

They sent an embassy to [Heraclius] the emperor of the Greeks saying: “God has given this land as an inheritance to our father Abraham and to his posterity after him. We are the children of Abraham. You have held our country long enough. Give it up peacefully, and we will not invade your country. If not, we will retake with interest what you have withheld from us.”64

The imagined reaction of Heraclius, reported in an eastern Christian source, was equally revealing. A military challenge from the “tents” of the south, at a time when the frontiers of both empires had been fatally weakened by decades of warfare, was only to be expected. But this would be different:

This people [the emperor said] is like an evening, between daylight and nightfall, neither sunlit nor dark … so is this people neither illumined by the light of Christ nor is it plunged into the darkness of idolatry.65

Let us see, in our next chapter, how the Christian populations of the Near East adjusted to the gigantic Arab empire which seemed to be founded on a troubling anomaly. In their opinion, Islam was an “in-between religion”. It was not pagan. It closely resembled Christianity and Judaism. Yet it was like neither of them. It was something entirely new. It was another monotheistic faith, thrown up by the political and religious turmoil of the Near East. And like Christianity, Islam also was convinced that it alone represented the culmination of God’s purposes on earth.