The more alignment you have, the more autonomy you can grant. The one enables the other.

—Stephen Bungay, author and strategy consultant

The Agile Release Train (ART) is a long-lived team of Agile teams, which, along with other stakeholders, develops and delivers solutions incrementally, using a series of fixed-length Iterations within a Program Increment (PI) timebox. The ART aligns teams to a common business and technology mission.

Each ART is a virtual organization (50–125 people, sometimes more or less) whose members plan, commit, and execute together. ARTs are organized around the enterprise’s significant Value Streams and exist solely to realize the promise of that value by building Solutions that deliver benefit to the end user.

ARTs are cross-functional and have all the capabilities—software, hardware, firmware, and other—needed to define, implement, test, and deploy new system functionality. An ART operates with a goal of achieving a continuous flow of value, as shown in Figure 1.

The ART aligns teams to a common mission and helps manage the inherent risk and variability of solution development. ARTs operate on a set of common principles:

A fixed schedule – The train departs the station on a known, reliable schedule, as determined by the chosen PI cadence. If a Feature misses a train, it can catch the next one.

A new system increment every two weeks – Each train delivers a new system increment every two weeks. The System Demo provides a mechanism for evaluating the working system, which is an integrated increment from all the teams.

A fixed PI timebox – All teams on the train are synchronized to the same PI length (typically 8–12 weeks) and have common iteration start/end dates and duration.

A known velocity – Each train can reliably estimate how much cargo (new features) can be delivered in a PI.

Agile Teams – Agile Teams embrace the Agile Manifesto and the SAFe values and principles. They apply Scrum, Extreme Programming (XP), Kanban, and other Built-In Quality practices.

Dedicated people – Most people needed by the ART are dedicated full time to the train, regardless of their functional reporting structure.

Face-to-face PI Planning – The ART plans its own work during periodic, largely face-to-face PI Planning events.

Innovation and Planning (IP) – IP iterations provide a guard band (buffer) for estimating and a dedicated time for PI planning, innovation, continuing education, and infrastructure work.

Inspect and Adapt (I&A) – An I&A event is held at the end of every PI. The current state of the solution is demonstrated and evaluated. Teams and management then identify improvement backlog items via a structured, problem-solving workshop.

Develop on Cadence; Release on Demand – ARTs apply cadence and synchronization to help manage the inherent variability of research and development. However, releases are typically decoupled from the development cadence. ARTs can release a solution, or elements of a solution, at any time, subject to governance and release criteria.

Additionally, in larger value streams, multiple ARTs collaborate to build larger solution capabilities via a Solution Train. Some ART stakeholders participate in Solution Train events, including the Solution Demo and Pre- and Post-PI Planning.

ARTs are typically virtual organizations that have all the people needed to define and deliver value. This arrangement breaks down any traditional functional silos (Figure 2) that may exist.

In the traditional functional organization, developers work with developers, testers work with other testers, and architects and systems engineers work with each other. While there are reasons why organizations have evolved in this way, value doesn’t flow easily within this type of structure, as it must cross all the silos. The daily involvement of managers and project managers is necessary to move the work across. As a result, progress is slow, and handoffs and delays rule.

In contrast, the ART applies systems thinking and builds a cross-functional organization that is optimized to facilitate the flow of value from ideation to deployment, as shown in Figure 3. Collectively, this fully cross-functional organization—whether physical (direct organizational reporting) or virtual (line of reporting is unchanged)—has everyone and everything it needs to define and deliver value. It is self-organizing and self-managing. This approach creates a far leaner organization, one where traditional daily task and project management is no longer required. Value flows more quickly, with a minimum of overhead.

ARTs include the teams that define, build, and test features and components. SAFe teams have a choice of Agile practices, based primarily on Scrum, XP, and Kanban. Software quality practices include continuous integration, test-first, refactoring, pair work, and collective ownership. Hardware quality is supported by exploratory early iterations, frequent system-level integration, design verification, modeling, and Set-Based Design. Agile architecture supports software and hardware quality.

Each Agile team includes five to nine dedicated individual contributors, covering all the roles necessary to build a quality increment of value for an iteration. Teams can deliver software, hardware, and any combination thereof. Of course, Agile teams within the ART are themselves cross-functional, as shown in Figure 4.

Each Agile team has dedicated individual contributors, covering all the roles necessary to build a quality increment of value for an iteration. Most SAFe teams apply a ScrumXP and Kanban hybrid, with the three primary Scrum roles:

Scrum Master – The Scrum Master is the servant leader for the team, facilitating meetings, fostering Agile behavior, removing impediments, and maintaining the team’s focus.

Product Owner – The Product Owner owns the team backlog, acts as the Customer for developer questions, prioritizes the work, and collaborates with Product Management to plan and deliver solutions.

Development Team – The Development Team consists of three to nine dedicated individual contributors, covering all the roles necessary to build a quality increment of value for an iteration.

The following program-level roles, in addition to the Agile teams, help ensure successful execution of the ART:

Release Train Engineer (RTE) – The servant leader who facilitates program-level execution, impediment removal, risk and dependency management, and continuous improvement.

Product Management – Responsible for ‘what gets built,’ as defined by the Vision, Roadmap, and new features in the Program Backlog. Product Management works with customers and Product Owners to understand and communicate their needs and also participates in solution validation.

System Architect/Engineer – An individual or team that defines the overall architecture of the system. This role works at a level of abstraction above the teams and components and defines Nonfunctional Requirements (NFRs), major system elements, subsystems, and interfaces.

Business Owners – Key stakeholders of the ART who have the ultimate responsibility for the business outcomes of the train.

Customers – The ultimate buyers of the solution.

In addition to these critical program roles, the following functions play an important part in ART success:

The System Team – Typically provides assistance in building and maintaining the development, continuous integration, and test environments.

Shared Services – Are specialists—for example, data security experts, information architects, and database administrators (DBAs)—who are necessary for the success of an ART but cannot be dedicated to a specific train.

Release Management – Has the authority, knowledge, and capacity to foster and approve releases. In many cases, Release Management includes Solution Train and ART representatives, as well as representatives from marketing, quality, Lean Portfolio Management, IT Service Management, operations, deployment, and distribution. This team typically meets regularly to evaluate content, progress, and quality. Its members are also actively involved in scope management.

ARTs also address one of the most common problems with traditional Agile development: Teams working on the same solution operate independently and asynchronously. That kind of operation makes it extremely difficult to routinely integrate the full system. In other words, “The teams are sprinting, but the system isn’t.” This increases the risk of late discovery of issues and problems, as shown in Figure 5.

Instead, the ART applies cadence and synchronization to assure that the system is sprinting as a whole, as shown in Figure 6.

Cadence and synchronization assure that the focus is constantly on the evolution and objective assessment of the full system, rather than its individual elements. The system demo, which occurs at the end of the iteration, provides the objective evidence that the system is moving forward.

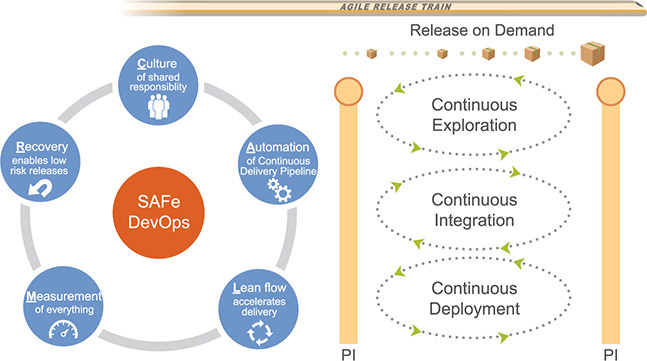

Every two weeks (and in aggregate, with every PI), the ART delivers a new system increment of value. This delivery cycle is supported by a Continuous Delivery Pipeline, which contains the workflows, activities, and automation needed to provide the availability of new features release. Figure 7 illustrates how these processes run concurrently and continuously, supported by the ART’s DevOps capabilities.

Figure 7. Continuous exploration, continuous integration, and continuous deployment are continuous, concurrent, and supported by DevOps capabilities

Each ART builds and maintains (or shares) a pipeline with the assets and technologies needed to deliver solution value as independently as possible. The first three elements of the pipeline work together to support delivery of small batches of new functionality, which are then released to meet market demand.

Continuous Exploration – The process of constantly exploring market and user needs and defining a vision, roadmap, and set of features that address those needs.

Continuous Integration – The process of taking features from the program backlog and developing, testing, integrating, and validating them in a staging environment so that they are ready for deployment and release.

Continuous Deployment – The process that takes validated features from continuous integration and deploys them into the production environment, where they are tested and readied for release.

Development and management of the continuous delivery pipeline are supported by DevOps, a capability of every ART. SAFe’s approach to DevOps uses the acronym ‘CALMR’ to reflect the aspects of Culture, Automation, Lean flow, Measurement, and Recovery.

Flow through the system is visualized, managed, and measured by the Program Kanban.

Releasing is a separate concern from the development cadence. While many ARTs choose to release on the PI boundary, more typically, releases occur independently of this cadence. Moreover, for larger systems, a release is not an all-or-nothing event; that is, different parts of the solution (e.g., subsystems, services) can be released at different times, as described in Release on Demand.

The organization of an ART determines who will plan and work together, as well as which products, services, features, or components the train will deliver. Organizing ARTs is part of the ‘art’ of SAFe. This topic is covered extensively in the Implementation Roadmap chapters, particularly in Identifying Value Streams and ARTs and Creating the Implementation Plan.

A primary consideration with ART organization is size. Effective ARTs typically consist of 50–125 people. The upper limit is based on Dunbar’s number, which suggests a limit on the number of people with whom one can form effective, stable social relationships. The lower limit is based mostly on empirical observation. However, trains with fewer than 50 people can still be very effective and provide many advantages over legacy Agile practices for coordinating Agile teams.

Given the size constraints, two primary patterns tend to occur (Figure 8):

Smaller value streams can be implemented by a single ART.

A larger value stream must be supported by multiple ARTs.

In the latter case, enterprises apply the elements and practices of the Large Solution Level and create a Solution Train to help coordinate the contributions of ARTs and Suppliers to deliver some of the world’s largest systems.

LEARN MORE

[1] Knaster, Richard, and Dean Leffingwell. SAFe Distilled: Applying the Scaled Agile Framework for Lean Software and Systems Engineering. Addison-Wesley, 2017.

[2] Leffingwell, Dean. Agile Software Requirements: Lean Requirements Practices for Teams, Programs, and the Enterprise. Addison-Wesley, 2011.

[3] Leffingwell, Dean. Scaling Software Agility: Best Practices for Large Enterprises. Addison-Wesley, 2007.