Agile software development and traditional cost accounting don’t match.

—Rami Sirkia and Maarit Laanti

Lean Budgets is a set of practices that minimize overhead by funding and empowering Value Streams rather than projects while maintaining financial and fitness-for-use governance. This is achieved through objective evaluation of working systems, active management of Epic investments, and dynamic budget adjustments.

Each SAFe Portfolio exists for a purpose: to realize some set of Solutions that enable the business strategy. Each portfolio must work within an approved budget, as the operating costs for solution development are a primary factor in economic success.

Many traditional organizations quickly realize, however, that the drive for business agility through Lean-Agile development conflicts with current methods of budgeting and project cost management and accounting. The result may be that the move to Lean-Agile development—and realizing the potential business benefits—is compromised. Even worse, it may simply be unachievable.

SAFe provides strategies for Lean budgeting that eliminates the overhead of traditional project-based funding and cost accounting. In this model, Lean Portfolio Management (LPM) fiduciaries have control of spending, yet programs are empowered for rapid decision-making and flexible value delivery. This way, enterprises can have the best of both worlds: a development process that is far more responsive to market needs, along with professional and accountable management of technology spending.

Every SAFe portfolio operates within an approved budget, which is a fundamental principle of financial governance for the development and deployment of products, services, and IT business solutions (software, hardware, firmware) within a SAFe portfolio. As described in the Enterprise chapter, the budget for each portfolio results from a strategic planning process (see Figure 1).

SAFe recommends a dramatically different approach to budgeting—one that reduces the overhead and costs associated with traditional cost accounting, while empowering Principle #9: Decentralize decision-making. With this new way of working, portfolio-level personnel no longer plan the work for others, nor do they track the cost of the work at the project level. Instead, the Lean enterprise moves to a new paradigm: Lean budgeting, beyond project cost accounting. This approach provides effective financial control over all investments with far less overhead and friction and supports a much higher throughput of development work (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 illustrates the five major steps to this future state:

Fund value streams, not projects.

Empower value stream content authority (e.g., Solution Management).

Provide continuous objective evidence of fitness for purpose.

Approve epic-level initiatives.

Exercise fiscal governance with dynamic budgeting.

Each of these steps is discussed in the next sections.

First, however, it’s important to understand the problems caused by the traditional project approach to technology funding:

Figure 3 represents the budgeting process of most enterprises before they move to Lean-Agile development. As shown in this figure, the enterprise is organized into cost centers. Each cost center must contribute to project spending or people (the primary cost element) to the new effort. This model creates some problems:

The project budget process is slow and complicated. It requires many individual cost-center budgets to fund the project.

It drives teams to make fine-grained decisions far too early in the ‘cone of uncertainty.’ If they can’t identify all the tasks, how can they reasonably estimate how many people are needed, and for how long? Their hand is forced.

People are assigned on a temporary basis. After the project is complete, people return to their organizational silo for future assignment within their cost center. And if they don’t, other planned projects will suffer.

The traditional model drives cost center managers to make sure everyone is fully allocated to one or more projects. However, running product development at 100 percent utilization creates an economic disaster [2], resulting in high variability between forecasted and actual time and costs.

The model prevents individuals and teams from working together for longer than the duration of a single project. This hinders learning, team performance, and employee engagement. Moreover, collocation is out of the question. If the project takes longer than planned—which it often does—many people will have moved on to other projects, and further delays will occur.

Once the project is initiated, the challenges continue. The needs of the business and the project change quickly. However, because the budgets and personnel are fixed for the project term, the projects can’t flex to the changing priorities (Figure 4).

The result is an organization that is unable to adapt to changing business needs without incurring the overhead associated with re-budgeting and reallocating personnel. The Cost of Delay (CoD)—the cost of not doing the thing that you should be doing—increases.

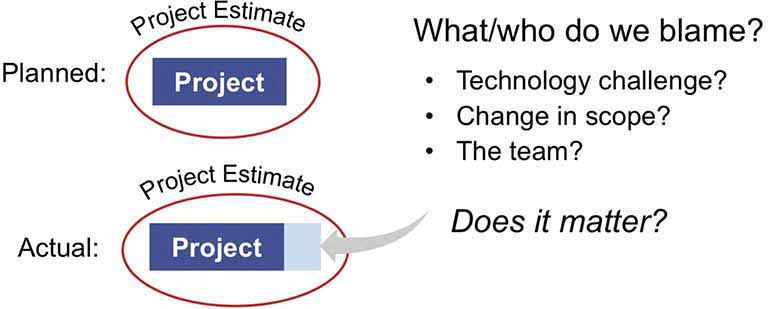

But we are not done. The product development personnel cannot innovate without taking risks [2]. Because this effort contains a high degree of technical uncertainty, it’s challenging to estimate product development. And everyone knows that most things take longer than planned. Moreover, even when things go well, stakeholders may want more of a specific feature. That requires approval from a change control board, which adds further delay. Again, project-based funding hinders progress, culture change, and transparency (Figure 5).

Figure 5. When overruns happen, project accounting and re-budgeting increase CoD and negatively impact culture

When schedule overruns occur for any reason, it’s necessary to analyze the variances, re-plan the schedule, and adjust budgets. Resources are scrambled. Personnel are reassigned. As a result, other projects are negatively impacted. Now, the ‘blame game’ sets in, pitting project managers against each other and financial analysts against the teams. Any project overrun has a budget impact, but the real casualties are transparency, productivity, and morale.

Traditional cost accounting undermines the goal of faster delivery and better economic outcomes. SAFe, however, provides five major steps to a better future state.

The first step is to increase empowerment and decrease overhead by moving the day-to-day spending and resource decisions to the people closest to the solution domain. Each value stream is assigned a budget (Figure 6).

This is a significant step, and it delivers several benefits to the Lean enterprise:

Value stream stakeholders, including the Solution Train Engineer (STE) and Lean Portfolio Management (LPM), are empowered to allocate the budget to the personnel and resources that make sense based on the current backlog and Roadmap.

Since value streams and Agile Release Trains (ARTs) are long-lived, people work together for an extended time, increasing their engagement, knowledge, competency, and productivity.

Self-organizing ARTs and value streams enable people to move from one ART and Agile Team to another, without requiring permission from management above the Program or Large Solution levels.

The budget is still controlled. In most cases, the expenses across a Program Increment (PI) are fixed or easy to forecast. As a consequence, all stakeholders know the anticipated spending for the upcoming period, regardless of which features are implemented. If development of a feature takes longer than planned, there’s no impact on the budget, and personnel decisions are a local concern (Figure 7).

Step 1 is a giant leap forward. Budgeting concerns aside, however, the enterprise still needs assurance that the value streams are building the right things. That’s one of the reasons the project model was created. SAFe provides for this possibility not through increased overhead of projects, but rather through the empowerment and responsibilities of Product and Solution Management. To give visibility to everyone, all upcoming work is conducted, contained, and prioritized in the Program and Solution Backlogs (Figure 8).

Work is pulled from the backlogs based on Weighted Shortest Job First (WSJF) economic prioritization. This model assures that sound and logical economic reasoning support these critical decisions and that the right stakeholders are involved.

Principle #5: Base milestones on objective evaluation of working systems provides the next piece of the puzzle. While the budget might be allocated in value stream–sized chunks, it’s reasonable for all involved to want fast feedback on how the investment is tracking. Fortunately, SAFe provides regular, cadence-based opportunities to assess progress every PI via the Solution Demo and, if necessary, every two weeks via the System Demo. Participants include such key stakeholders as the Customer, Lean Portfolio Management, Business Owners, and the teams themselves. Any fiduciary party can participate and receive assurance that the right thing is being built in the right way and that it’s meeting the customer’s business needs, one PI at a time.

While the rule is that each value stream is funded, there is an exception to that rule. By their very definition, epics are large enough and impactful enough to require additional approval. Often these initiatives affect multiple value streams and ARTs, and their costs may run into many millions of dollars. That is why all epics need review and LPM approval through the Kanban system and a Lean business case, whether they arise at the portfolio, Program, or Large Solution level (Figure 9).

Epics may be funded by tapping a portfolio budget reserve, by reallocating people or money from one value stream to another, or by simply accepting that an epic will consume a significant portion of an existing value stream budget. In any case, epics are large enough to require analysis, as well as strategic and financial review and decision-making. That scale, along with the Lean business case, is what makes an epic, an epic.

Although value streams are largely self-organizing and self-managing, they do not launch or fund themselves. As a result, LPM has the authority to set and adjust the value stream budgets within the portfolio. To respond to change, funding will vary based on business needs (Figure 10).

Nominally, these budgets can be adjusted twice annually. Less frequently, and spending is fixed for too long, limiting agility. More frequently, and the enterprise may seem to be very Agile, but people are standing on shifting sand. That creates too much uncertainty and an inability to commit to any near-term course of action.

LEARN MORE

[1] Special thanks to Rami Sirkia and Maarit Laanti for an original white paper on this topic, which you can find at http://pearson.scaledagileframework.com/original-whitepaper-lean-agile-financial-planning-with-safe/.

[2] Reinertsen, Don. Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation Lean Product Development. Celeritas Publishing, 2009.