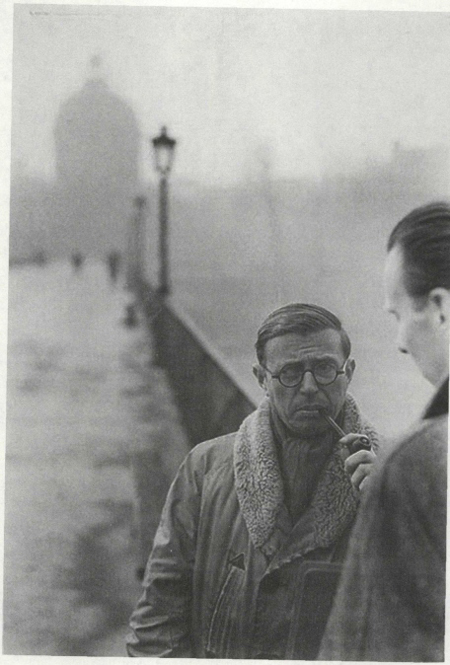

IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, belief became the central issue. "Every minute of the day I ask myself what I could be in the eyes of God," Jean-Paul Sartre puts in the mouth of a character in his play Le Diable et le bon dieu {The Devil and the Good Lord). "Now I know the answer: nothing. God does not see me, God does not hear me, God does not know me." Sartre did not take his atheism lightly. He devoted a large part of his most important philosophical work, L'Etre et le ne'ant (Being and Nothingness), to the problem of God and at one point, like Bourdelle, compared belief in God to a belief in the centaur: "To say that the centaur does not exist," he wrote, "is by no means to say that it is not possible." In a famous lecture on "Existentialism" which he gave at the end of the second war he began with the God problem, stating that his aim was not to demonstrate that God did not exist, but rather to show that "even if God existed that would change nothing." Man, with a consciousness which gave him total freedom of choice, projected himself as God: that was the principal argument of the sage of Saint-Germain-des-Pres.

Sartre is not popular today. "Unhappy 100!" chimed the Times Literary Supplement at the centenary of his birth in 2005. "Sartre's philosophy was never very coherent and means nothing now; his novels are unreadable" crowed Paul Johnson in the Literary Review. Comments in the French press were not much better. Memories are bitter because of Sartre's slide into Communism and the extreme left which began—one can give it a date—in 1952, around six months after the premiere of Le Diable etle bon dieu. The image many have of Sartre is that of an old man haranguing a few workers from the top of a barrel outside the Renault factory at Boulogne-Billancourt, or of him distributing a Maoist rag in Rue Daguerre, near Place Denfert-Rochereau, or of his mad defence on television of the Baader-Meinhof terrorist band.

Before 1952 Sartre was an individualist. The closest he came to recognizing collective action in Being and Nothingness, published in 1943, was—appropriately for us—in his example of commuters in the metro. Down in the métro in 1943 the traveller would look into the wan faces of other commuters and wonder silently what was their story—their broken families, their deported loved ones, their lost soldier. The last métro before the midnight curfew became a morbid ritual in occupied Paris, yet another kind of danse macabre. Only here there were no partners. All was performed in solitude. Sartre evoked the rhythm produced by striding commuters in the passageways, comparing it to the "cadenced march of soldiers," the "rhythmic work of a crew" (he had served on the front and had been a prisoner of war) or "dancers on the stage:" "the rhythm to which I give birth is born in connection with me and laterally as collective rhythm . . . It is finally our rhythm." But that is as far as he was willing to go; before 1952 Sartre's interest was focused on the free individual, necessarily finding himself in conflict with the freedom of others. In his métro example the signposts are all projected at me; "I am aimed at": "I avail myself of the opening marked 'Exit' and go through it." Sartre climbs the steps, with his mind still free; he turns home, alone. It is the hour of silent curfew throughout most of Sartre's hefty philosophical tome. How then could he subsequently align himself with the collectivist Communists? How was it possible?

Saint-Germain-des-Pres is the closest-knit, cosiest quartier and also one of the oldest in Paris. True, the boulevard itself has, like all of Haussmann's thoroughfares, cut a blind swathe right through the heart of the historic quartier: ancient buildings have literally had their northern half sliced off in order to make way for the boulevard. But people cross the boulevard as if the boulevard did not exist—it is the one spot in Paris where pedestrians have priority over the cars, and so it was in Sartre's day. On the north side of the boulevard are the cafés Deux Magots and the Flore, on the south side, opposite, is the Brasserie Lipp. The marketplace on the south side—it is one of the few examples of Napoleonic architecture in Paris, square and uninteresting—is on the site of a fair that had been held here since at least the early Middle Ages. The twelfth-century abbey tower ascends to the north, defying the clouds, and establishing a powerful point of stability for the community that surrounds it. In the abbey's interior you will find the original display of Gothic coloured sacred stone: pillars of red and gold, and a high starry ceiling that are enough to challenge the thoughts of any doubter of God. On the south wall are inscribed the names of near five hundred parishioners mortspour la France in the war of 1914-18, and well over a hundred mortspour la France—soldats, re'sistants, deportes, fusilles, victimes civiles in the war of 1939-45.

Religion, fair and festival were what kept Germanopratins (as the happy residents are known) together for so many centuries. Trade was vigorous in the Middle Ages and Renaissance because outside the city walls of King Philip Augustus (which followed the current Rue de Seine) one escaped the city's taxes. The abbey's farmlands provided fruit and vegetables, while the clerics encouraged the spread of books, paintings and engravings; there was plenty of music performed in the streets. Most of the abbey properties were destroyed during the French Révolution, but the market remained, as did the books, the paintings, and even the music.

War left its imprint. Because Saint-Germain was outside the city walls, Viking marauders were allowed to run amok in the abbey and its surroundings; in the fourteenth century it was the turn of the English. The near total destruction of the abbey during the Révolution was in response to a war with the rest of Europe that didn't seem to be going too well. But it was the last two world wars that most affected what one finds today in Saint-Germain.

Speak of Saint-Germain-des-Pres to a Parisian and his eyes will go misty and his hands rotate as he conjures up images of intellectuals regaling themselves in cafés, of jazz bands pounding out all night in the cellars, of painters, actors and actresses joining hands with famous writers in the late 1940s and early 50s—one long, gigantic party after the Second World War. Yet there had been an earlier celebration. "The great epoch of Saint-Germain-des-Pres was before the war," says the painter and actor Roger Edgar Gillet, who turned twenty at the Liberation. Before the war you could find great writers like Roger Martin du Gard, André Gide and Francois Mauriac having coffee in the Deux Magots. The Flore next door was considered a bit of a pit; many of its clients were Poles, who are still today an important minority in the quarter. The main bookstore then was across the street at the Divan, run by Monsieur Martineau, who suffered from a chronic ulcer. Others preferred the pretty young owner of Champion, down the road by the Seine. Yes, those were serious days born out of the poetry and disillusionment of the First World War. Then, with the Occupation, writers and artists closed in on themselves. 'And they liberated themselves," Gillet goes on. "Yes," he ruminates, "after the war, came the explosion."

Sartre himself thought the critical change occurred during the war itself. This was when the move was made by the intellectuals from Montparnasse to Saint-Germain-des-Pres; and it was during the Occupation that the Flore triumphed over the Deux Magots. Sartre said, "Montmartre became a forbidden place because: (i) it was cold at the Dome; (2) the grey mice of Boulevard Raspail arrived lugging sachets of tea, pots of butter and jam, and white bread: it was intolerable; (3) the métro Vavin was closed." Paul Boubal, the new owner of the Flore, installed a pot-bellied coal stove and, just as important, a telephone. German soldiers and collaborators frequented the Deux Magots; they rarely made an appearance at the Flore. During the last winter of the Occupation people passed mornings, afternoons and evenings in Boubal's Flore; one lady spent two to three hours in the toilets every day Sartre thought, "Either she's got enteritis, or she's reading compromising papers." Boubal became King of the Quarter, ran several dubious financial affairs, threw prostitutes out of his café and, with the Liberation, convinced trumpeter Boris Vian that he was going to run for Prime Minister.

In 1942 Boubal noticed a little man arrive every day at opening, leave at midday and return in the afternoons to stay until closing time. He would always be accompanied by an attractive but very serious-looking young lady and they would spend their time scribbling at different tables. This went on for months. One day the telephone rang to ask for Monsieur Sartre. Boubal knew a man called Sartre and he was not there. The caller insisted that he was, so Boubal announced the name. Up got the little man: "I am Monsieur Sartre." The telephone calls became so numerous that Boubal put a special line through to Sartre's coffee table.

Boubal was witness to the making of Being and Northingness and Sartre's roman-fleuve, Les Chemins de la liberte (The Roads to Freedom). By the time Sartre had got to his first plays— Huis clos (No Exit) was put on at the Theatre du Vieux-Colombier at the time of the Normandy landings—he was so well known that he took to hiding in the café Pont-Royal in the distant Septième Arrondissement. Within weeks the term "existentialist" was being applied to the cafés, the restaurants, the jazz cellars and all the mad youth, the zazous, crowding into an ecstatic, liberated Saint-Germain-des-Pres.

What was an existentialist? The popular weekly Samedi Soir ran an article in May 1947 on the troglodytes of Saint-Germain that defined an existentialist as one who stayed in a Hôtel for a month and didn't pay the bill. When the manager says he will seize his bags the existentialist clambers up the steps on all fours and puts on as many shirts and trousers as he can and slinks off to another hotel. After several months he has only one pair of trousers left, he can't sleep, so he spends his nights in the Bar Vert on Rue Jacob, writing on the lavatory and telephone cabin walls existentialist graffiti. . . And so the article goes on. Parisians remained poor for a long time after the war; conditions were worse in 1947—when there were a series of Communist-led strikes — than they had been at the war's end. People stayed in the cafés because they were warm, they ate in the little restaurants because there was nowhere else one could find food, and photographs of zazous dancing to the jazz bands with trousers held up by string show that the description in Samedi Soir contained a grain of truth. People often looked ragged and dirty (though the women maintained an aura of Parisian chic that had astonished American GIs when they arrived in 1944). Sartre himself was seen, the four seasons round, wearing the same dirty woollen sweater. The historian Alistair Home recalls meeting him shortly after the war: "Smelling like a goat, he rather set the tone. If ever there was a philosopher guilty of the sin Socrates was accused of, being a false corrupter of youth, Sartre seemed to be it." Part of this may have been just appearance (I myself met Sartre, years later, in the Rotonde—he was dressed in a dark blue suit and did not smell like a goat): at the École Normale Superieure right-wing students were known as "the Clean" while the left-wingers were called "the Dirty"; Sartre was one of the Dirty, putting on plays that shocked the Director and hammering out, to the delight even of the Clean, American jazz on the piano. Even when Sartre started earning big money he stayed in a hotel; it was considered "bourgeois" to live in anything as comfortable as a three-room flat. In the last years of the war Sartre kept lodgings in the Louisiane, on Rue de Seine, one of the "pimp-and-prostitute hotels" where Henry Miller lived in the 1930s.*

In the cafés, the existentialist "family" sat at separate tables from the "bande a Pre'vert" and would rarely even be seen in the same locale as members of the Communist "cell." Part of the Germanopratin legend is that spirits were so jubilant around those little tables that all social and political barriers vanished. 'An extreme leftist would talk with an unconditional Gaullist, a Catholic with an anticlerical or ajew," recalled Daniel Gelin. "The only thing de rigueur was tolerance." Claude Mauriac, a Catholic, remembered a truly surrealist scene on the terrace of the Deux Magots one warm evening in June 1946. André Breton, former surrealist and arch-Communist, was surrounded by his old disciples when Antonin Artaud, who had been thrown out of the Party, walked by: "he gave a very low bow and Breton bowed even lower; it was from below the coffee tables that they eventually started talking: a most amiable chat."

All those imbibers at Saint-Germain would have told you they were "anti-Fascists," but the term was getting a little worn around the edges— even in 1945. Sartre described the atmosphere in the Flore during the Occupation: "The permanent clientele was composed of absolutely closed groups . . . It was like an English club. People would come in, recognizing everybody; each one knew down to the slightest detail the private life of his neighbour; but between groups one never said 'bonjour.'" There was always the fear of mouches (flies) and corbeaux (crows)—spies. Most of those present would have been party to what Jean Cassou, critic and veteran anti-Fascist, called the refus absurde, an absurd refusal to accept the fact of occupation, though often counter to self-interest. But that was hardly enough to create a community of interest; each one stood on his guard. Here were the essential ingredients of the existential mind.

Étienne Antonetti, a teenager who danced in the cellars of the Liberation, who loved Juliette Greco in her slinky black dresses, and enjoyed being in the company of Camus, Sartre and Picasso, thought there was something about being an "existentialist," even if he did not read Being and Nothingness at the time: "Our two maitres dpenser, Sartre and Camus, brought, each in their manner, a kind of direction, a moral sense to life, and that really marked me, yes. That 'liberty of choice which determines the individual,' that was a part of me, I practised it."

One should not underestimate the huge impact of Sartre's thought on his age. Sartre's initial understanding of freedom was drawn on two forms of being, the chaos of the universe of objects (the en-soi) and the structured consciousness of man (thepour-sot) which perceives this universe and constantly yearns to colmprehend it. In contrast to the German phenomenology of G. W F. Hegel, Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, thepour-soi in Sartre's schema never arrives at its end, which ideally would be a "higher" synthesis in the form of an en-soi-pour-soi: God. Instead the pour-soi is destined to fail in its goal through an unavoidable process of self-negation; as Sartre explained, "man is doomed to be free," though that freedom can never be complete. In a critical chapter on "The Situation" Sartre outlined the limitations which consciousness was constantly running up against: the place I inhabit, my past, my environment (even when changing place), my neighbour and my death—Sartre quotes André Malraux's terrifying comment that "death transforms life {determined by my choices] into destiny [my past as perceived only by others]."

Being and Nothingness is at times baffling. But persistence is rewarded by a privileged look into the mind of a genius. There are not many writers who have demonstrated such an array of talents as Sartre; he wrote a great philosophical work, a first-rate play (Huts clos), a splendid novel (La Nause'e) and a wonderful work of autobiography (Les Mots)—and he produced a lot else besides. His experience as a novelist and a playwright allowed him to provide graphic examples as demonstrations of his formidable philosophical theories. Being and Nothingness is filled with inkpots, cups, coffee tables, waiters in a rush, suspicious strangers, spies, anonymous crowds, oppressive police forces, anti-Semites, sadists, resisters and an anticipated liberation. It is above all a philosophical work born out of the German occupation of Paris: the reader finds Sartre working at the café de Flore or in the confines of his Hôtel room; there are shortages and absences; one discovers the impotence of an isolated civilian; one shares with him his despair, his hopes, his search for meaningful acts; his disappointment in the face of the constant annihilation of his will.

To demonstrate how freedom is born not out of its end goal but from its initial negation—"that the practical conception of freedom is wholly negative"—Sartre takes the example of the curfew: "Remove the prohibition to circulate in the streets after the curfew, and what meaning can there be for me to have the freedom . . . to take a walk at night?" It is the negation of freedom which makes one conscious of freedom. That "surging forth," that birth within the pour-soi, the "original choice," the doomed effort to transcend the pour-soi of human consciousness into the en-sot of the objects about us always begins with a negation, with a threatened annihilation of the subject. The mountain outside the window is a colourful part of the landscape during a summer holiday in the Alps until the idea is born in one's consciousness to climb it: then the mountain becomes a challenge, a nightmare, a life-threatening object. This inkpot in front of me is not a coffee cup—it is through that "not" that human consciousness distinguishes one object from the other and imposes order on the chaotic universe.

But in young Sartre, during the Occupation, that order is never complete, it is frustrated. The fact of frustration creates an existential anguish, a fear of the void and a desire to escape the choices before us. Man escapes the terrifying choices laid before him by putting on a mask of conformity, by living in "bad faith" with his pour-soi, his consciousness. Sartre is very cruel here, and utterly uncompromising. A man suffers from an inferiority complex because he wants to be inferior. A woman behaves as if being exploited because that is the easy way out of her physical condition. AJew in occupied Paris behaves as a Jew; a worker takes himself to be a worker. But it can be otherwise. In a toughly worded passage—remember this was published in 1943 — Sartre laid out the kind of choice facing the individual endowed with freedom, whatever his environment. "The most atrocious situations of war, the worst tortures do not create an inhuman state of affairs," he wrote: "there are no inhuman situations; it is only through fear, through flight and through recourse to superstitious forms of conduct that I decide that conditions are inhuman; but this decision is itself human and in thus acting I bear the total responsibility for my deeds." Acts performed out of fear, evasion or the resort to religion were for young Sartre made in bad faith. One had to take the bitter pill and embrace the situation, alone. Sartre appealed in print, in 1943, for "engagement" to an "authentic" freedom, a commitment to resistance. He contrasted the "partisans of liberty" to the determinists who believed that man's consciousness and his choices were conditioned by something beyond his control—for the Marxists by the economic regime, for the Freudians by the unconscious, for the Christians by God. Sartre's idea of "engagement," as he expressed it in the 1940s, was not simply political; it lay at the base of the individual's whole project of life. The freedom for which man strived, in a universe without God, was the only absolute capable of generating a system of values and of providing his being with meaning. But, though promised in the concluding paragraphs of Being and Nothingness, the work on an existentialist value system never got written; events instead would push Sartre, disastrously, down a more collectivist, political path of engagement.

THE CAFÉ—JUST like the metro—provided an excellent example of how limited a collective consciousness, the nous-sujet, was. The sense of togetherness in these cafés was a Germanopratin legend that did not have much foundation in fact. Being and Nothingness gives a striking example of what café life was actually like. Sartre is sitting on the terrace of his café observing other clients while they observe him "in the most banal kind of conflict with the Other." Then suddenly on the street opposite a velo-taxi collides with a delivery tricycle: "we watch the event, we take part in it;" temporarily—like the commuters in the metro— one is engaged in the "we." The Sartrean "family," Christians and Communists alike, all participate, but once the event is over they return to their coffee and silence.

The abbey was right next to the principal cafés; it marked the central point of the Germanopratin community. Parallel to the boulevard ran the narrow street of Rue Jacob, with its clubs, its restaurants and publishing houses. Virtually opposite the Echelle de Jacob was a small provincial house with a tree in front of it: the house is still there, looking as provincial as ever, and the tree now reaches beyond the roof. In 1946 the editors Paul Flamand and Jean Bardet set up the new publishing firm of Le Seuil here; the top floor became the headquarters of the widely read Catholic journal Esprit. Just down the road was the Eitions Gallimard; its top floor was occupied by Sartre's new journal, Les Temps Modernes, founded in autumn 1945. Christians and existentialists formed a mirror image of each other, and not just in stone.

A series of events going back to the Dreyfus Affair in the 1890s had isolated practising Christians in France from the political and social mainstream. The republican separation of Church and state in 1905 had meant they could expect no support from the state, and the papal ban in 1926 on Action Française — mouthpiece of the extreme right with which the French Church had been identified—suggested that Christianity could not risk political affiliation. Many of the Catholic elite avoided the bitter choice Pope Pius XI presented them: they formally submitted themselves to the ban while secretly flouting it, the kind of hesitancy that made them easy targets for the atheist charge of "bad faith." The novelist Georges Bernanos maintained his political allegiance to Action Française and thus deprived himself of the holy communion for years.

Then there were the converts. Since the late nineteenth century a number of intellectuals, in the face of rapid de-Christianization, had converted to the Catholic faith. Some of these conversions were dramatic, such as that of the poet Paul Claudel in Notre Dame Cathedral on Christmas Day, 1886, or of Charles Peguy on the eve of the First World War. "What am I?" the philosopher Jacques Maritain, co-founder of E$-prit, wrote to his friend Jean Cocteau. 'A convert. A man God has turned inside out like a glove." Sartre himself was fascinated by the process of conversion—there are so many references to it in Being and Nothingness that one wonders if he was not tempted to take the step himself (Albert Schweitzer was, after all, his uncle). Many of the converts were the children of mixed family backgrounds: Catholics married to Jews, or Protestants living with Catholics (such as in Sartre's family). All these people had taken, in the face of adverse opinion, a definite choice that would influence what Sartre called their "life project." And all of them, as a result of the historical dilemma of Christianity at that moment, were men stranded alone with their conscience—a very existential situation.

All this demonstrates a complicity between Sartrean and Christian thought, and it did not stop there: the very origin of existential philosophy in France was Christian.

Gabriel Marcel was one of the converts, though his acceptance into the Church was hardly dramatic. The Catholic novelist, Francois Mauriac, wrote to him one day, pointing out what a lot they had in common. "Why aren't you one of us?" asked Mauriac, so "one of us" he became. The two dramatic events in his life were the death of his Jewish mother when he was four, which put his whole life in a "desert universe," and the First World War when, too weak to fight, he served with the Red Cross's information bureau: every day he would see relatives of men missing in action so that "every index card became a heart-rending personal appeal." Born in 1886, Gabriel Marcel was sixteen years older than Sartre. His life was marked by the empty and the absurd. This influenced the philosophy he developed, in fragments, during the years that followed the First World War.

His biographer M. M. Davy called him the "itinerant philosopher"; he travelled a lot and, although he passed his agregation in philosophy at the tender age of twenty, he never held a teaching post. He lived in a flat in that significant frontier-land between the Luxembourg Gardens and the Sorbonne, an area which, though beyond the formal limits of the Sixieme Arrondissement, was considered one of the "protectorates" of Saint-Germain-des-Pres in the heyday of the Germanopratin empire. What interested Marcel in his empty universe was the human relationship. He used his talents in music to express the unexpressible features of that relationship; and, like Sartre, he wrote for the theatre as a means of demonstrating the central role played by the "mot" and the "toi." His first major philosophical work, Etre et avoir (Being and Having), which he began at the end of the Great War and completed in 1933 (to be finally published in 1935), anticipated Sartre's ontology by a whole generation. The themes of Marcel's thought are recognizably Sartre's.

Marcel by the 1930s had, after the experience of the Great War, the rise of new brutal dictatorships, the disorientation of the Church and the weak response of Europe's democracies, become convinced that his world—the "broken world" he called it in one of his plays—had been emptied of humanity; it was like a watch which ceased to tell the time, or a body whose heart had stopped beating: things seemed to go on as before, but there was nothing inside; the world had lost its soul. During the Occupation he wrote a series of essays that were published in 1945 as Homo Viator, or "Man the Traveller"—unlike Sartre, Marcel did not manage to get his works past the Vichy censors. His message was a clear call to "engagement." "The true patriot cannot believe in the death of his country," he wrote, "he does not even consider he has the right to believe it."

But for Marcel the Liberation of 1944-45 was no cause for celebration. In Les Hommes contre I'humain (Men against Humanity) he described the world that emerged from the war as even more "dehumanized" than it had been in the 1930s. He had no sympathy for the ideology of Resistance that conducted purges on suspected collaborators, he did not join the ranks of anti-imperialists and de-colonizers, he disliked the ruling post-war penchant for "the spirit of abstraction" and warned against becoming the "vassals" of organized political allegiance. As the leading proponent of what by now was known as "Christian Existentialism," Marcel took Sartre's Being and Nothingness to task for taking—with its pour-soi and en-soi—a step backwards into dualism; Sartre, he thought, was artificially separating thought into idealistic and materialistic domains and risked falling into the trap of pure materialism. These comments were published in 1951, shortly before Sartre slid, irredeemably, into the extreme left.

THE MATERIALIST T EM PTAT I ON for Sartre—as Marcel perceived it—lay just around the corner from the café de Flore, on the Rue Saint-Benoit. Communist journalists used to meet in the Montana and neighbouring cafés; formal meetings of the Germanopratin "cell," no. 722, took place in the nearby Salle de Geographie on Boulevard Saint-Germain, after which the elite of the Party would withdraw for an encounter at No. 5, Rue Saint-Benoit (it was the district of saints), in the flat of Marguerite Duras, then a slim brunette author with a bark. It was the relations Sartre had with the Communists, along with divisions in his own "existentialist" camp, that drove him over the brink in 1952.

The Communists were themselves divided by the developing Cold War, which by 1948 was getting very hot. "If the Red Army Occupied France What Would You Do?" asked the political weekly Carrefour. In interviews, members of the French Communist Party turned the question round, "Why not the American army?" Anti-Americanism reached fever pitch amongst Communists and fellow-travellers. One Communist paper, Action, began a serious campaign against Coca-Cola, warning that it was "a drug liable to provoke violence." Communist frenzy could be turned on its own people, sometimes in quite ludicrous circumstances. Marguerite Duras and six of her friends were expelled from the Party in 1949 because of a conversation in the café Bonaparte during which Laurent Mannoni, journalist at Ce Soir, described Laurent Casanova, editor of La Nouvelle Critique and patron of Communist intellectuals, as a "Grand Mac," a pimp. Jorge Semprun, active in another journal, reported this to the Central Committee and, as a result, earned a reputation as a mouchard. The affair was still being heatedly discussed on French television fifty years later.

Expulsion from the Party was, for a Communist militant, like the break-up of a marriage or the loss of a close relative. The sociologist Edgar Morin, who had joined the Party at the end of the war, has spoken of the "great warmth of comrades, the wonderful feeling that radiates from the words 'c'est un copain,'lje suis un copain.'" Communist camaraderie was an adolescent game that married well with the jazz culture of Saint-Germain; but its somewhat murderous "anti-Fascist" rhetoric makes hard reading today. Many of the participants—two of Marguerite Duras' husbands, for example—had spent time in Nazi concentration camps. Communists tended to survive. A Communist network inside the camps placed comrades in relatively safe administrative positions— both Jorge Semprun and the Italian author Primo Levi have described the cruel logic behind this. As a result Communist resisters in France tended to survive. Well might the French Communist Party of the postwar years boast of the "75,000 fusilles": most of the 40,000 resisters executed by the Nazis were in fact not Communist—they had been denounced to the Nazis by the Communists.

The subject of concentration camps was a particularly sensitive one after 1945 and a major cause of division among comrades and fellow-travellers— not the Nazi camps, but the Soviet ones. Sartre was dragged into the debate.

The whole quarrel began when a Soviet defector to the United States, Victor Kravchenko, published in 1947 a French translation of his I Chose Freedom. The Communist-run Les Lettres Francaises accused the book of being written by anti-Soviet specialists in US intelligence. Parts of the original English version, it was true, had been subject to intrusive editing in order to make it "fit for the American reader," but that Kravchenko was its author could never be doubted. Kravchenko filed a double suit for criminal libel against Les Lettres Francaises and came over to Paris to push his case through. When he appeared, in January 1949, in the Salle de Geographie at the opening of the trial the world press was present. The intellectuals of Saint-Germain-des-Pres had never had such coverage before. The Soviet Union flew in a fleet of witnesses, including Kravchenko's former wife; but they did the Communist cause no good. "What I did, I did for the whole world, for all free people," said Kravchenko and, supported by devastating testimony on the barbarity of Soviet camps, he won his case.

For the Communists of Saint-Germain, worse was to follow. In November 1949 a left-wing Socialist who had himself done time in the Nazi camps, David Rousset, published in the conservative Figaro Lit-teraire an 'Appeal for the constitution of a committee of enquiry into the Soviet camps." The camps, reported Rousset, "are placed under the direction of sections of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs which carry the name Gulag." Rousset had not fully grasped the complexity of Soviet camp administration, but this was the first time the term "Gulag" was used in the West.

It caused an uproar within the Germanopratin community of deportees, represented by a Communist front organization called the "National Federation of Deportees, Internees, Resisters and Patriots" (FNDIRP) under Pierre Daix, a pure Stalinist who was in large measure responsible for the expulsions of Marguerite Duras and friends. Emergency meetings of Cell 722 were held, insults were exchanged; Duras' ex-husband, Robert Antelme, claimed that the alienation of workers under "capitalism" was just as inhuman as the Soviet Union's concentration camps. He deplored the anti-Communist tone of Rous-set's article. Antelme's position was endorsed by Sartre in his Temps Modernes. Rousset filed a suit for libel; Daix and his director at Les Lettres Francaises were fined as a result of graphic court testimony on the horrors in Soviet camps. The Communists of Saint-Germain were quite evidently living in "bad faith."

WITH IN TWO YEARS, Sartre was behind them. Every Sunday afternoon in the late 1940s there would be an editorial meeting, in the Gal-limard building, of Les Temps Modernes. Most of the young present were either Party members or fellow-travellers, despite a vicious Communist campaign against Sartre—"the hyena," the impenitent individualist, the "disciple of the Nazi Heidegger" and the inventor of a philosophical system that was both "nauseating and putrid." Sartre had a soft spot for the young, especially young women—and it may have been this that was the cause of his slide leftwards.

When asked how he managed to handle so many "contingent loves" at the same time, Sartre admitted that he had to resort to lying. In the more important political domain he lied, too. The ridiculous positions he took as a "public man" after 1952 naturally caused people to wonder about his responsibility as a writer and his philosophy of engagement, liberty, authenticity and freedom of choice. Was man really as radically free as Sartre had initially insisted? Or was his behaviour determined by deep, hidden forces beyond his control? If the latter were true, Sartre's whole philosophical system crumbled.

Most influential on Sartre's political position was his assistant editor at Les Temps Modernes, the Sorbonne professor of philosophy, Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Merleau-Ponty lived on Rue Jacob and, though the author of the most cerebral, abstract works, had an enormous sense of fun; he was the only philosopher in Saint-Germain to dance with the girls in the jazz clubs —the others used to cogitate in a dark corner with their friends, half-hidden by a pall of cigarette smoke. In stark contrast to his behaviour, Merleau-Ponty's philosophy was sombre, ambiguous and empty of any hope of discovering the secret of the chaotic universe in which he lived—a reflection of his unhappy, if privileged, childhood. Merleau-Ponty's sentences ran on forever; one could never be sure whether priority should go to the well-camouflaged main phrase or the multiple qualifications that enveloped it. He rejected Sartre's division of being into the pour-soi and the en-soi, which he thought too close to Descartes' duality of mind and body to be comfortable, and instead he offered the reader the idea of a "body subject" that combined the spiritual and the material—in this sense he was closer to the Christian thought of Gabriel Marcel than Sartre. But there was no religious faith in Merleau-Ponty to act as guide; just the self-organization of the thinking subject, an "en-etre," which the American intellectual historian H. Stuart Hughes translated as "being with it." It was a philosophy full of doubt, the forerunner of that of today's cultural relativists. Indeed, Merleau-Ponty spoke in his last major work, before he was struck down by a heart attack at the age of fifty-three in 1961, of writing a "relativism beyond relativism." By that time he had withdrawn from political activity entirely and had retreated into a study of the problem of perception.

But in the late 1940s he, and not Sartre (or Albert Camus), was the driving force in the politics of Saint-Germain's existentialists. The book that gave him political leadership was Humanisme et terreur, an apology for Soviet terrorism published in 1947. Juliette Greco described an enjoyable evening spent with him, drinking punch and dancing: "He accompanied Jujube [as Greco described herself] to her door and then returned home to his Humanisme et terreur." Sartre affirmed the importance of Merleau-Ponty's political influence in the obituary he wrote for Les Temps Modernes in 1961: "He was my guide; it was Humanisme et terreur which made me take my step. This little book, so dense, opened up both method and object: it was the snap of the fingers that pulled me out of inactivity."

The book advocated a "Marxism of expectant waiting," one that would give the Soviet Union the benefit of the doubt, an "understanding without adherence and of free examination without belittling"—in other words, a blank cheque, a refusal to accept the anti-Communism of the American camp while taking advantage of the margin of safety in European events that would allow one to remain neutral and thus save the peace. Typical of his relativistic stance, Merleau-Ponty compared French and British "terror" in their colonies with Stalin's crimes, which needed to be "understood." Merleau-Ponty argued that Soviet leaders were more honest than those of the West in admitting to their own terrorist practices. By the mid-1950s he deeply regretted having written this perverse little book.

On 25 June 1950 North Korean troops, with the encouragement of the governments in Moscow and Peking, invaded South Korea. Merleau-Ponty recognized that the Soviet Union was the principal aggressor, as did Sartre's other wayward collaborator Albert Camus, whose last illusions about the nature of Soviet Communism had been destroyed by the evidence of the Soviet concentration camps. Sartre, on the other hand, joined the majority of left-wing intellectuals in accusing the United States of warmongering.

Merleau-Ponty's subsequent drift into relativism and metaphysics had been anticipated in his earlier writings, which were not exactly a ringing endorsement of commitment. As for Camus, he had never been a philosopher; he is remembered today for his novels—L'Étranger (The Outsider), La Peste (The Plague), La Chute (The Fall)—not his essays. L'Homme révoké (The Rebel), published in a critical year for Sartre, 1951, which contained some marvellous portraits of Marx and Lenin, and with comments even more incisive on the Marquis de Sade, Nietzsche and the French Surrealists, was analytically weak: all it argued was that, faced with the savage, formless movement of history, man should endeavour to respect human life and remain moderate. Sartre, in his stinging criticism of the book the following summer, rightly pointed out that Camus was attempting to have the best of both worlds, the ethics of the violent rebel and personal happiness; this kind of ambiguity could not be endorsed by the philosopher of "engagement," existential Sartre. "Friendship can become totalitarian," wrote Sartre, and he accused Camus of pursuing "only literature"; Sartre broke with Camus for good. For a couple of years Camus withdrew from writing altogether, concentrating instead on the production of his plays. He then seemed to be moving in the direction of intensive literary creation when his career was tragically cut short by a motor accident near Sens in January i960.

From a strictly philosophical point of view, Camus' story is marginal. As for Merleau-Ponty, he had marginalized himself by pursuing a purely relativistic strain of thought that committed him to nothing. In contrast to both Camus and Merleau-Ponty, Sartre had set himself a clear choice: the wrong choice. He plunged into it with gusto.

By the time the Korean War broke out he was living under a punishing regime of political activity, playwriting, journalism and a night-time reading of the works of Karl Marx—not to mention his complex love affairs. He was smoking two packets of unfiltered Boyards, drinking coffee and tea by the litre, and chewing up to twenty pills of corydrane—a popular 1950s mixture of aspirin and amphetamines—every day Simone de Beauvoir, his companion, recorded in her diary that he did not sleep for three nights out of the week, and when he did decide to go to bed he gulped down half a bottle of whisky and four or five sleeping pills. To arrive at this point of clear choice Sartre was, as he graphically put it himself, "breaking the bones in my head."

In Being and Nothingness Sartre described the futility of man's efforts fully to apprehend himself and his surroundings in terms of Henri Poincare's sphere, in which the temperature decreased as one moved from the centre towards the surface. Try as they might, individual beings could never reach the surface because the lowering of temperature produced in them a continually increasing contraction: "they tend," wrote Sartre, "to become infinitely flat proportionately to their approaching their goal, and because of this fact they are separated from the surface by an infinite distance." The surface was the etre-en-soi, the autrui, the Other— a living being always beyond reach.

Pushed to its logical limit this Other was, in the way Sartre described human consciousness, the omnipresence of God, an unrealizable ideal towards which man was constantly striving, though always falling short. If he did not push himself to his limits, man would fall by the wayside in "bad faith," and reduce himself to acting out the role that the Other's presence wanted him to be: a "waiter," a "worker," a "slave," a "Jew," even a "writer." Though he could never reach that unattainable surface, man had to strive to do so; in Sartre it was a process of continual birth within oneself, a surging forth, a transcendence from oneself to the Other, and ultimately an impossible "conversion"—an image which was repeated throughout his great philosophical work. In his wartime play, Huis clos, he showed the cost of not striving towards the unattainable—in the form of three people, a male coward, a female narcissist and a lesbian, who had to live eternity together: "Hell is other people," remarks one of the characters. "I did not mean to say that our relations with others are always poisonous," elaborated Sartre in an interview in 1965. "I wanted to say that if our relations with others are warped and tainted, then the Other can only be hell." Man had to make an open choice and swallow the bitter pill, otherwise he was damned.

So in 1952, Sartre swallowed the bitter pill. For years he had been groping from a position of aggressive neutrality—a "socialist" Europe which stood outside the influence of the two superpowers — to one of complete cooperation with the Communists. On the Soviet camps, Sartre clung to Merleau-Ponty's Soviet apology of 1947 that capitalism had committed as many evils as those of Stalin's regime. On social policy he argued that the Communist Party most clearly represented the interests of the "proletariat"—a term that he and other intellectuals used with careless abandon to mean any group that appeared poor and exploited. "It is impossible to take an anti-Communist position without being against the proletariat," he explained glibly in 1951. But it was the Soviet Union's Peace Movement, which had been gathering momentum since its first congress held in Wroclaw in Poland in 1948, that eventually brought Sartre with so many other Western intellectuals round to the Communist camp.

Peace was the old dream of Paris's Liberation; the call for peace was a sure magnet for a Germanopratin who had lived through those dramatic months of transition. In La Douleur, Marguerite Duras recorded her impressions of the end of April 1945, shortly after her ex-husband, Robert Antelme, returned from a German camp: "Paris lights up at night. The Place Saint-Germain-des-Pres is illuminated as if by headlights. The Deux Magots is jam-packed. It is too cold for people to sit on the terrace. But the little restaurants are also crammed. I walk outside. Peace seems imminent. I return home in a rush. Pursued by peace."

Ah, peace! Picasso drew his famous dove for the Communist-sponsored World Congress of Partisans of Peace, held in April 1949 in Paris's Salle Pleyel. Ah, peace! Sartre still hesitated at that time, not least because of the foul language the Communist press was deploying against him. It was the Korean War which decided him, not least the American bombing of North Korea. Ah, peace! Many in Paris were awaiting a nuclear war, instigated by the United States. Ah, peace! In a long essay, "The Communists and the Peace," which was published in Les Temps Modernes during the summer of 1952 (at the time of his break with Camus and Merleau-Ponty), Sartre argued that the Soviet Union was a purely defensive power faced with destruction by the men of the Pentagon. He began a series of trips to Russia and to brother Socialist states, such as popular democratic China and Cuba, once it had become Communist. He abandoned his work on ethics, which he had promised in Being and Nothingness; and turned his attentions instead to the impossible marriage of existentialist phenomenology to collectivist Marxism. The work nearly killed him, and it shows; The Critique of Dialectical Reason is a truly impossible read.

We can be even more precise about the moment of Sartre's slide. In May 1952 he was in Rome enjoying the company of his Italian

Communist friends when he heard that a Communist demonstration in Paris had been repressed and the Party's rotund, voluble

leader, Jacques Duc-los, had just been arrested. Sartre went on record later as saying that this was the instant of his conversion to Communism: "When I came back hurriedly to Paris, I had to write or I would suffocate." Unfortunately, a whole cohort of

the Western world's best brains followed Sartre in his conversion, down that route to the absurd.

* The Hôtel still stands at the sharp intersection of Rue de Buci and Rue de Seine, to the side and above a bountiful fruit and vegetable shop. It even houses a genuine writer, an Egyptian, who has been living there for over fifty years.