6

Contested Formations

Our “Godfather” Problem

If Christianity is . . . an alternative form of cultural joining and interaction, then Christian communities and their theologians will have to reckon with their legacy of ecclesial failure.

Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination

Picturing Competing Formations

in The Godfather

“I believe in America.” These are the first words of Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather. A supplicant Amerigo Bonasera has come to the office of Vito Corleone as part of a Sicilian ritual. On the day of his daughter’s wedding, the Godfather is doling out favors in a spirit of largesse, a benevolent patriarch showering blessings on the community. Bonasera has come looking for nothing less than “justice” for his daughter, who has been beaten and disfigured. “I believe in America,” Bonasera confesses. “America has made my fortune.” But American justice has let him down. The perpetrators receive a suspended sentence and walk free. And so he comes to the Godfather: “For justice,” Bonasera tells his wife, “we must go to Don Corleone.” After expressing disappointment that Bonasera sees this as merely an economic rather than a familial exchange, the Godfather grants his wish. Bonasera can count on justice, which, as becomes clear, is reduced to the lex talionis.

Already foreshadowed in this first scene is the complex overlap and intertwining of religion and violence, capital and capitulation, ritual and retaliation. On the one hand, the entire world of the film is framed by the rituals of the church—from the opening wedding rite to the baptismal rite at its climax. Indeed, the very title and dynamics of The Godfather hearken back to the baptismal liturgy. The world of “business” in the film is conducted by “families,” and no one is more of a “family man” than Don Corleone. (“Do you spend time with your family?” he asks his godson, Johnny Fontaine. “Because no one can be a man who doesn’t spend time with his family.”) Because the families are bathed and constituted by the rituals of the church, the blending of bloodlines by liturgical practices forges bonds that are charged with ultimacy. “Corleone is Johnny’s grandfather,” Tom Hagen, the adopted son, observes. “To the Italian people that is a very religious, sacred, close relationship.” In a way, you’d almost be tempted to say this is a world held together by the bonds of love.

On the other hand, the business conducted by these families is the very antithesis of peace and makes a mockery of the very rites they participate in. The bonds of love turn out to be merely a kind of in-group consolidation against enemies. The business bleeds into all-out war, and their work becomes synonymous with illicit trade, intimidation, exploitation, and violence. No one would mistake their “business” for the kind of economic life described in Catholic social teaching.

It is this aspect of the Godfather’s world that the youngest son, Michael (played by Al Pacino), is determined to escape. When his girlfriend Kay first meets the family, Michael insists: “That’s my family, Kay. It’s not me.” To resist the family business, he also has to resist the family’s bonds and rites. And so he’s an aloof presence at the opening wedding festival, hovering on the margins. But that changes when his father, the Godfather, is attacked and almost killed. This triggers something in Michael, an angry loyalty that snaps tight the bonds of family and pulls him in. “I’m with you now,” he whispers to his father in a hospital bed, kissing his hand. “I’m with you now.” He joins the family business and so spirals into the world of violence and retaliation, power and domination.

This trajectory culminates when Connie, Michael’s sister, asks Michael to be her child’s godfather at the same time that he assumes responsibility for the family business.1 The narrative arc comes full circle. Once again we are at the intersection of the church and the family as Michael assumes the role of godfather in the baptismal liturgy. But here too, at the climax of the film, the dissonance between their ritual participation and the nature of the “family business” is starkly portrayed through one of the master sequences of film editing. In a dizzying array, we cut back and forth from the hushed rites inside the church to a series of brutal assassinations ordered by Michael Corleone. Coppola is ruthless in this sequence, bringing us face-to-face with violence while also immersing us in the theological thickness and specificity of the baptismal rite. As we witness the horrible violence of the family business, we witness a solemn confession of the gospel.

The priest breathes on the child, symbolizing the renewal of the Holy Spirit, and then salts the baby’s mouth, ears, hands in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Ghost while the camera transports us to a scene of grisly execution.

The priest poses the Credo to Michael, who is standing as the child’s godfather.

“Michael, do you believe in God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth?”

“I do,” Michael replies.

“Do you believe in Jesus Christ his only Son, our Lord?”

“I do,” Michael insists.

“Do you believe in the Holy Ghost, the holy catholic church?”

“I do,” he responds.

But the hits keep coming: enemy after enemy falls prey to his assassination commands while we are taken back inside the church to see Michael participate in the exorcism.

“Michael Francis, do you renounce Satan?” the priest asks.

“I do renounce him,” Michael affirms, while his henchmen carry out his diabolical commands.

“And all his works?”

“I do renounce him.”

“And all his pomps?”

“I do renounce him,” is the continued reply.

The entire sequence ends with a benediction: “Go in peace, and may the Lord be with you. Amen.” But all the while the pomps and works and wiles of the evil one are carried out in the name of the family’s “business,” capital sins committed in the name of capital and “justice.”

The Godfather amounts to a visual parable of a challenge and critique that dogs the Cultural Liturgies project: while I extol the formative power of historic Christian worship practices, it would seem that there can be—and are—people who have spent entire lifetimes immersed in the rites of historic Christian worship who nonetheless emerge from them not only unformed but perhaps even malformed.2 Or, to put it otherwise: clearly, regular participation in the church’s “orthodox” liturgy is not enough to prevent such “worshipers” from leaving the sanctuary to become (sometimes enthusiastic) participants in all sorts of unjust systems, structures, and behaviors. Like the people of Judah critiqued by the prophet Jeremiah, we can “come through these gates to worship the Lord,” announce our allegiance, and superstitiously claim protection (“This is the temple of the LORD!”), but spend the rest of the week burning incense to the gods of mammon, prostrating ourselves to the idols of power and domination, baking cakes for the queen of heaven (Jer. 7:1–26).

Let’s call this “the Godfather problem”: you can liturgically renounce the works of the devil and carry them out at the same time. Liturgical participation is no guarantee of formation in the virtues or the acquisition of the fruits of the Spirit. Liturgy is not a silver bullet that guarantees holiness; nor is there any guarantee that mere worship attendance is a sufficient condition to make the people of God a “contrast” society. To say that there is would be to lapse into a kind of liturgical determinism that assumes a simplistic view of formation and a kind of “purity” about the church that is misplaced.3

Does the Godfather problem undercut the core argument of the Cultural Liturgies project? I don’t think so. But it is a fundamental challenge that needs to be accounted for—a challenge I’ve noted from the beginning of the project.4 If liturgy forms us by conforming us to the image of Christ (Rom. 8:29), then why are Christians so often conformed to the world (per Rom. 12:2)? Answering that question is the focus of this chapter.

Concurrent Formation and the Dynamics of Deformation: Case Studies

In many ways, though the Cultural Liturgies project is focused on the primacy of liturgical formation in Christian discipleship, this was largely prompted by the reality of our cultural assimilation. How are we to make sense of the fact that Christians can have a wealth of knowledge about Christianity and yet live as practical naturalists, giving themselves over to ways of life that are, in some respects, the very antithesis of shalom? If the core goal of my project has been to argue that our loves are rightly ordered through the “habitation of the Spirit” that is Christian worship, this is in no small part a response to the way we are co-opted by rival stories and visions of the good life. In short, the emphasis on counter-formation in worship is a fire-meets-fire response to the deformation of our loves that manifests itself as conformity to “the world.” That conformity, I’ve argued, is not usually the result of having been convinced by ideas but rather the result of our hearts and longings (and hence action) being conscripted by rival liturgies.5 So if we have emphasized the significance of liturgical formation, that is not because Christian worship is sui generis or some deus ex machina intervention into our lives. Rather, it is because we are liturgical creatures who are always already being shaped by some liturgies. In other words, “liturgy” is as much an account of the problem (of assimilation) as it is a solution.

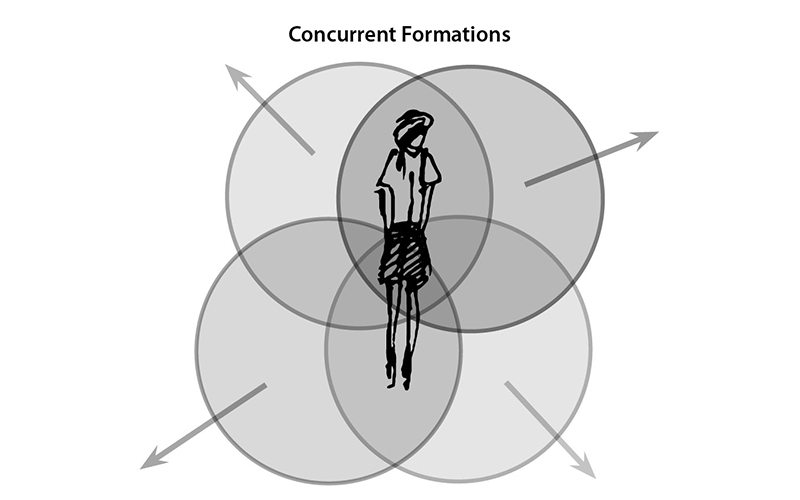

And, in fact, it’s important to appreciate the complexity of being-in-the-world and recognize that we are always already subject to multiple communities of practice, caught up in multiple (and rival) liturgies that enact competing visions of the good life. There is no “purity” for liturgical creatures in the saeculum; I am never caught up in just one tradition or liturgical community. Even if we prioritize the church’s worship as the primary site of the Spirit’s sanctifying transformation, we are never only subject to the church’s worship, nor is the church’s worship a “pure” instantiation of the kingdom. I am subject to competing apprenticeships of the heart. I am concurrently enrolled in competing pedagogies of desire. And the church—both as a sacramental institution and as a people—is caught up in a web of liturgies that constitute “the world.” So the emphasis on liturgical (re)formation is rooted in a creational anthropology that recognizes humans are liturgical animals, creatures of habit whose loves are (de)formed by some liturgy. “Everybody worships,” as David Foster Wallace reminded us.6

But this emphasis on liturgical formation of rightly ordered love is often met with a pointed question: Aren’t there all kinds of Michael Corleones in the world, people who have spent a lifetime “practicing” a ritualized Christian faith with what seems to be little evidence of any sanctification? Don’t we see all kinds of examples in which Christian liturgical participation has not been reformative and seems to have done nothing to stave off cultural assimilation? Indeed, isn’t it disturbing how much and how often such ritual performances of faith can become caught up in the most egregious expressions of injustice? While we’ve claimed that it is participation in the thick strangeness of historic Christian worship that makes the church a “peculiar people,” aren’t there all kinds of people who have been immersed in such liturgies who seem exactly like their neighbors—happy consumers pursuing their self-interests, caught up in the same injustices that come with privilege, content to shore up the status quo? So it would seem that liturgy is not the answer to our cultural assimilation.

I want to tackle these questions head-on by first considering a couple of case studies that are, I believe, some of the starkest examples of “the Godfather problem.” If there is going to be any “answer” to this challenge, it needs to be articulated on the other side of actually going through the problem. So after laying out the force of this challenge in these case studies, I’ll then sketch the facets of a complex, nuanced response that, I will argue, requires us to take seriously an emerging conversation between ecclesiology and ethnography.

Case Study 1: Whiteness and the Inadequacy of Liturgy

Akin (and indebted) to the work of Stanley Hauerwas, my argument regarding liturgical formation is broadly “MacIntyrean,” inheriting Alasdair MacIntyre’s retrieval and renewal of an Aristotelian and Thomistic emphasis on habit, character, and virtue—and hence narrative, tradition, and community. While in chapter 2 I addressed Jeffrey Stout’s critique of this framework, perhaps the most stinging critique of this theological project was penned by Willie James Jennings in his magisterial work The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race.7 Jennings is also diagnosing Christianity’s fundamental and blameworthy assimilation to a dominant culture—in this case the church’s long capitulation and contribution to a racialized world fraught with harrowing injustice and inscrutable evil that was, time and again, baptized with “Christian” justification and even blessing. While Christian theology over the past generation has fixated on the effect of the Germanic Enlightenment and the theoretical legacies of modernity,8 Jennings brings us face-to-face with the material, embodied realities of modernity that find expression in the Iberian conquest and subsequent European colonization. While we have worried whether theology bought into the rationalism of Descartes or the liberalism of Locke, Jennings documents the heinous capitulation of the church to a very different aspect of modernity: the slave trade. The flipside of modernity’s rationalization was a capacity to diminish and devalue black bodies, engendering a default racialization that characterizes modern life (particularly in the United States). “Europeans,” Jennings argues—and he means European Christians—“enacted racial agency as a theologically articulated way of understanding their bodies in relation to new spaces and new people and to their new power over those spaces” (CI, 58). Paralleling my earlier discussions of “social imaginaries” in Desiring the Kingdom and Imagining the Kingdom, Jennings documents the emergence of “whiteness” as an imaginary: “Whiteness from the moment of discovery and consumption was a social and theological way of imagining, an imaginary that evolved into a method of understanding the world” (CI, 58).9

What good, Jennings asks, did “the tradition” do to prevent such capitulation to injustice? The church-as-polis did nothing to prevent the construal of Africans as chattel, commodifying human beings made in the image of God. The seeming magic of “the liturgy” did nothing to prevent or even temper this descent into inhumanity. To the contrary, the rituals of church simply enfolded such injustices into the narrative. In the opening of his book, Jennings recounts a heart-rending scene captured for posterity by Gomes Eanes de Azurara (or Zurara). Chronicler for Prince Henry of Portugal in the fifteenth century, Zurara recounts a turning point in the fate and power of the Portuguese Empire: On August 8, 1444, a ship has arrived from Africa bearing “black gold,” 235 enslaved Africans who represented the new global power of Portugal. Rather than unloading them under the cover of night, perhaps hiding the shame of this “necessary evil,” Infante Henrique choreographed a public spectacle at dawn, one bathed in ritual. “This ritual was deeply Christian,” Jennings comments,

Christian in ways that were obvious to those who looked on that day and in ways that are probably even more obvious to people today. Once the slaves arrived at the field, Prince Henry, following his deepest Christian instincts, ordered a tithe be given to God through the church. Two black boys were given, one to the principal church in Lagos and another to the Franciscan convent on Cape Saint Vincent. This act of praise and thanksgiving to God for allowing Portugal’s successful entrance into maritime power also served to justify the royal rhetoric by which Prince Henry claimed his motivation was the salvation of the soul of the heathen. (CI, 16)10

Indeed, this ritual signals the insidious way the tradition’s narrative can enfold injustice and sanctify it by re-narration. So “the Christian story,” rather than “sanctifying them in truth,” remakes the world to conform to the truth of colonial enslavement.11 In his chronicle, “Zurara deploys a rhetorical strategy of containment, holding slave suffering inside a Christian story that will be recycled by countless theologians and intellectuals of every colonialist nation. The telos and the denouement of the event will be enacted as an order of salvation, an ordo salutis—African captivity leads to African salvation and to black bodies that show the disciplining power of the faith” (CI, 20). And the church, rather than being the counter-polis of resistance, happily accepts the tithe of black flesh. “This act is carried out inside Christian society, as part of the communitas fidelium. This [slave] auction will draw ritual power from Christianity itself while mangling the narratives it evokes, establishing a distorted pattern of displacement” (CI, 22).

Thus Jennings directly challenges the sort of “virtue project” articulated by Hauerwas and others (like myself), which places so much confidence in the power of tradition and ecclesial formation to create a counterculture. The idealism of this claim, Jennings argues, conveniently ignores the church’s capitulation to the horrors of modernity.12 “One could fault MacIntyre but more importantly those theologians who have followed his thinking on tradition for not seeing the effects on the Christian tradition triggered by the modernist elements at the beginning of the age of Iberian conquest.” We need to “watch how traditioned Christian existence, first that of the Iberians and then that of all Europeans, fundamentally changed as they ascended to hegemony in the New Worlds” (CI, 71). Why didn’t their tradition, their narrative, and their liturgy prevent this stark failure of holiness and sanctification?13 Indeed, this is less an assimilation or capitulation to some “external” unjust society and more an internal projection from the church itself: “It would be a mistake to see the church and its ecclesiastics as entering the secular workings of the state in the New World,” Jennings cautions, “or to posit ecclesial presence as a second stage in the temporal ordering of the New World. No, the church entered with the conquistadors, establishing camp in and with the conquering camps of the Spanish. The reordering of Indian worlds was born of Christian formation itself” (CI, 81).

So the church’s liturgy, tradition, and narrative can’t be simplistically construed as an antidote to modernity or injustice. To the contrary, the Jesuit José de Acosta Porres “thus fashioned a theological vision for the New World that drew its life from Christian orthodoxy and its power from conquest.” His work “reveals in a very stark way the future of theology in the New World, that is, a strongly traditioned Christian intellectual posture made to function wholly within a colonialist logic. . . . The inner coherence of traditioned Christian inquiry was grafted onto the inner coherence of colonialism” (CI, 83). Drawing on Pierre Bourdieu’s account of habitus, Jennings points out that Acosta’s inculcation into an ecclesial habitus did nothing to temper his complicity with colonialism: “When Acosta looked out onto the New World, the Christian habitus in which he had been shaped became the expression of a colonialist logic” (CI, 104).14

The result was not merely an epiphenomenal sin on top of an intact foundation of holiness—an appendage of injustice tacked onto an otherwise healthy body of Christ.15 Rather, the result was “the emergence of [a] Christian-colonial way of imagining the world,” a racialized worldview that was inseparable from the “Christianity” that journeyed across the Atlantic on ships. Jennings voices the jarring question this chapter aims to answer: “How is it possible for Christians and Christian communities to naturalize cultural fragmentation and operationalize racial vision from within the social logic and theological imagination of Christianity itself?” (CI, 208). He answers the question by documenting how, and to what extent, Christianity became inextricably bound up with the twin logics of nationalism and capitalism: creation is reduced to property, and property is there for plundering. In a careful analysis I can’t replicate here, Jennings shows how this was connected to the “vernacularization” of Christianity—projects of translation (of the Bible, of liturgy, of hymnody)16 that “facilitated the dissemination of the idea of a nation and the expression of cultural nationalisms”—which then transformed space where whiteness governs (CI, 208–9), “a geographic expansion of identity around the body of the master, the body of whiteness” (CI, 241).17 As Jennings shows, the architecture of the slave owner’s home became a wider social architecture, creating a distorted social space that was synonymous with the productive, consumptive nation (CI, 241–47). “What connected these spaces was the racial imagination that permeated both the creating and shaping of perception and helped to vivify both spaces” (CI, 241). The result is what Charles Taylor would call a “misprision”18 of Christianity, or what Jennings seems to suggest is a misperformance of biblical Christianity that both caused and is the fruit of a malformed body of Christ. Christianity was effectively trumped by these rival logics even when it claimed to be engaged in a “missional” endeavor.

How to account for this profound “ecclesial failure”? What happened? How could the community that heralds the gospel of grace so easily morph into the community that trades in black flesh? Jennings locates this misprision and failed performance in the heart of our project: a distorted habitus that reflects a failed pedagogy. “Christianity is a teaching faith,” he emphasizes. “It carries in its heart the making of disciples through teaching.” However, that doesn’t mean that all the “teaching” the church carries out is Christian teaching. A formative Christian pedagogy must be carried out “inside its christological horizon and embodiment, inside its participatio Christi and its imitatio Christi” (CI, 106). But this is precisely where the colonialist pedagogies of “New World” Christianity failed so miserably: “The colonialist moment indicates the loss of that horizon,” Jennings shows, and its replacement by a “racial optic.” The result is an inversion whereby Christian confession and theology are subordinated to a different imaginary, a different logic—that of capital.19 There is a collusion and elision here that continues to haunt us: “The operation of forming productive workers for the mines, encomiendas, haciendas, the obrajes, and the reducciones merged with the operation of forming theological subjects” (CI, 107). “Teaching” here is not merely didactic information transfer. Indeed, what is taught is precisely a habitus that is caught through a kind of “pastoral power” (per Foucault) that suffuses this formative dynamic in a wide web of relationships, systems, and institutions. “This is the ground upon which the ideologies of white supremacy will grow: a theologically inverted pedagogical habitus that engenders a colonialist evaluative form that is disseminated through a network of relationships, which together reveal the deep sinews of knowledge and power” (CI, 109).

And what was “caught” in this web? Specifically, and fundamentally, a parody of the Christian doctrine of creation, a rival story of where we are and who we are that was all the more seductive because it came with a distorted Christian accent. The anthropology yielded by this rival creation story collapses humanness with whiteness and reduces black bodies to property, all under the guise of a perverted doctrine of creation captive to the logics of colonialism and capitalism.20 “The profound commodification of bodies that was New World slavery signifies an effect humankind has yet to reckon with fully—a distorted vision of creation” (CI, 43). But again, this “doctrine” of creation was disseminated less as a propositional dogma to be affirmed and more as a subconscious—but nonetheless powerful—social imaginary that was absorbed in the policies and practices of colonial configurations of the world. And as Jennings concludes: “If Christianity is going to untangle itself from these mangled spaces, it must first see them for what they are: a revolt against creation” (CI, 248).21 This will require “a different social imagination,” not just refinement of our theological syllogisms. It requires a healing of the Christian imagination that addresses “an abiding mutilation of a Christian vision of creation and our own creatureliness” performed by colonialist innovation. Christians, says Jennings, must “recognize the grotesque nature of a social performance of Christianity that imagines Christian identity floating above land, landscape, animals, place, and space, leaving such realities to the machinations of private property. Such Christian identity can only inevitably lodge itself in the materiality of racial existence” (CI, 292).

This distorted theology of creation arrived with the slave ships. Indeed, as Equiano’s subversive narrative suggests, the slave ship is “creation” in colonialist theology. The slave ship (re)makes the world. “The slave ship positions itself next to creation, next to the creating act of creation’s recapitulation. It is a moment of metaphysical theft, an ambush of the divine creatio continua, the continuing creative act” (CI, 186).

Equiano’s Interesting Narrative (1789) steals creation back by deconstructing the heretical version of the slave ship’s doctrine of creation. Since the slave ship remakes the world, in a sense when Equiano boards the ship, he is stepping into a new world. “Equiano must make sense of his life no longer in a village configured in ancient space, but on ships configured by global commerce and the calculus of exchange” (CI, 188). Left in the hold to despair, Equiano sees the reality before him: “I now saw myself deprived of all chance of returning to my native country, or even the least glimpse of hope of gaining the shore” (CI, 188). This “new world” of the ship—the “creation” into which he has been loaded—is governed by market logic. “Unbridled European consumption and production transubstantiated African bodies. Black bodies juxtaposed to such things as East Indian textiles, Swedish bar iron, Italian beads, German linens, Brazilian tobacco flavored with molasses, Irish beef, butter, pork, Jamaican rum, and North American lumber announce ownership. In godlike fashion, merchants and traders transformed African bodies into perishable goods and fragile services” (CI, 188).

Equiano directly challenges this perverted “creation” with a scriptural imagination that calls out the heretical rendition, calling it back to orthodox Christianity. Thus his Narrative “carries the demand for humanizing relationships as central to the performance of Christian identity, the very identity claimed by his white readers” (CI, 189). Lamenting his separation from his sister—so common in the slave auctions governed only by the logic of the market—and despairing at her fate, Equiano utters a lament, a prophetic prayer: “O ye nominal Christians! Might not an African ask you, learned you this from your God? who says unto you, Do unto all men as you would men should do unto you? Is it not enough that we are torn from our country and friends to toil for your luxury and lust of gain? Must every tender feeling be likewise sacrificed to your avarice?” (CI, 192).

Equiano—who “read the world scripturally”22 (CI, 194)—is diagnosing the extent to which the white theological imaginary has replaced scriptural lenses with colonialist, capitalist spectacles. The functional worldview of that imaginary is one to which Christianity is subject, not one in which a gospel imagination governs. And so Equiano’s conversion is also an inversion. Converted on a slave ship named Hope, his narrative challenges and overturns the slave-ship creation narrative. “He brought the remade world into the world created by God who saved him” (CI, 197). The creation called into existence by Christ, sustained by the ascended Lord, is the creation in which the Word became flesh and endured death on a cross. And that same Jesus meets the broken Equiano on the Hope. That encounter and conversion unleash the forces that will upend the perverse bastardization of creation carried on board that same ship. Equiano “assumed a prophetic position as one who spoke from within the Christian tradition, arguing through its internal logics and utilizing its scriptural wisdom. However, what he was not fully aware of was how far down the absurdity reached into Christianity’s performance in the new worlds” (CI, 183).

This is seen in Equiano’s appeal to his baptism. His protest was not just an abstract, dogmatic claim. It was also rooted in liturgy, in the rites of worship. Hastily sold by the captain of one ship, without a chance to say farewell to friends or crew that had befriended him, Equiano tried to argue for freedom with his old and new masters: “I told him my master could not sell me to him nor to any one else . . . I have served him . . . many years, and he has taken all my wages and prize-money, for I only got one sixpence during the war; besides this I have been baptized; and by the laws of the land no man has a right to sell me” (CI, 182). Equiano (rightly!) sees the rite of baptism as an ontological change, the basis for equality and an indication of everything that’s wrong with commodification of human beings. But then Jennings points out the limits of this appeal: “We also see the symbol of Christianity’s fundamental limitation, the inefficacy of baptism in the presence of a racial calculus. As performed in the slaveholding Christian West, baptism enacted no fundamental change in the material conditions of Christian existence” (CI, 182). Our liturgies are liable to co-option by trumping imaginaries. And so we feel the force of the question that occupies us in this chapter: Why should we think liturgy is the counter-formative discipline we’ve suggested?

But also constructively: “What does it mean to form faithful people, given the complex social situations for our theological pedagogies?” (CI, 285). While we need to grapple with the ubiquity and ingression of perverted creation heresies carried on slave ships and in marketized distortions of human nature, we must also refuse the temptation to concede these are “natural,” just “the way things are.” The hope of the gospel is a reimagining of the world as the creation that holds together in Christ (Col. 1:15–20), which comes with the hope of imagining our own re-formation in ways that can resist the pedagogies of white supremacies and other injustices woven into the liturgies of Western market societies. With Equiano, we are called to “attempt to imagine belonging and relationship beneath the guiding hand of God through relations that are fundamentally diseased and reflective of the remade world” (CI, 186). How to remake the remade world? How to reconfigure the disconfiguration of creation we have inherited? And how to be faithful to the word of a resurrected Jew in the midst of modernity’s markets? How to sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?

Picturing Liturgical Capture

in The Mission

In discussions of economics, regulation, and public policy, you are bound to run into the concept of regulatory capture. First articulated by the Nobel laureate George Stigler, regulatory capture describes a situation in which a government agency that is supposed to regulate an industry becomes dominated by the very industry and companies it is supposed to police. So instead of acting in the public interest to protect consumers, the environment, and the common good, the “captured” agency acts in ways that benefit the industry. In a common analogy, it is said that in such cases the gamekeeper turns poacher.

This happens because companies have vested interests in controlling whatever would like to control them. Since regulation could put a cramp on profits, industries are more motivated than a broader consumer public to lobby, persuade, and influence regulatory agencies. And since regulators need the sort of expertise that only people in the industry have, it is often industry experts who become the regulators. In the most thorough form of “deep capture,” as Jon Hansen and David Yosifson describe it, the regulator begins to think like the regulated industry.23 At that point, the capture is complete: it has been internalized.

Perhaps we could analogically describe a situation of “liturgical capture”—one in which the liturgies of the church are captured and dominated by the disordered, rival liturgies they are meant to counter. Given that the rival polis has a vested interest in minimizing challenges and resisting the control of other liturgies, the rites of the market and empire can seek to absorb the rites of the church as merely a subservient, qualified expression that can be disciplined by market forces—either by compartmentalizing the religious to the merely “spiritual” or by privatizing the religious to interior, domestic life (both of which amount to the same thing).24

This is pictured in maddening, heartbreaking ways in Roland Joffe’s award-winning film The Mission, starring Jeremy Irons as Father Gabriel and Robert De Niro as Rodrigo Mendoza, the mercenary/slave trader turned Jesuit. Set in 1758 in the blurry borderlands hidden deep in the jungle of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, it opens with the retrospective voice of the cardinal who has been dispatched from Europe to resolve a tension in the colonies. As a result of a treaty between Spain and Portugal, a vast swath of the jungle and its inhabitants—the indigenous Guaraní—have been transferred from Spanish to Portuguese rule. But this isn’t merely an administrative transfer between distant colonial powers. There is a very tangible and dire consequence: the Guaraní would now be at the mercy of Portugal’s slave trade. Officially, Spain has repudiated slavery, but in fact the Spanish governor, Don Cabeza, is deeply invested in the slave trade. And one of his most important “providers” is the mercenary hunter Rodrigo Mendoza.

Complicating this “industry opportunity” is the presence of Father Gabriel and a community of Jesuits who have risked their lives, and suffered martyrdom, to bring the gospel to the Guaraní. The peaceful placidity of their witness is embodied by the plaintive notes of Father Gabriel’s oboe as he first invites, and encounters, the Indians. With stuttering breaths that betray his fear, Father Gabriel nonetheless comes to them with a new song that the Guaraní will make their own.25 As the cardinal remarks in his report to the pope, “With an orchestra the Jesuits could have subdued the whole continent.” Gabriel’s evangelism is aesthetic.

“So it was,” the cardinal narrates, “that the Indians of the Guaraní were brought to the everlasting mercy of God . . . and the short-lived mercy of man.” For European politics is playing itself out in these distant colonies, and the missions and their inhabitants are pawns that will have to be sacrificed. If the Jesuits refuse to evacuate the missions in South America—thereby exposing the Guaraní to become chattel in Portugal’s slave trade—then the Jesuit order will be expelled from Europe. Furthermore, the missions have become industry rivals, generating self-sustaining economies that are the envy of the Portuguese governor, Senhor Hontar. The missions have become too prosperous, he remarks to the cardinal. “You should have achieved a noble failure if you wanted the approval of the state. There’s nothing we like better than a noble failure.”

But the Indians refuse to leave, and neither will the Jesuits at the mission of San Carlos, facing excommunication as a result. Father Gabriel refuses to abandon his Guaraní sisters and brothers and so remains in solidarity, though taking up a pacifist stance. Rodrigo, who has by this point undergone a radical conversion and become a Jesuit, also refuses to abandon them. But his response is that of the proto-liberation theologian: he is staying to fight, along with other priests.

What is nothing short of disgusting is how the politics of the papacy allows itself to be cowed by the politics of the nation-state. This has happened in no small part because the papacy has configured the church as it if were a state, another rival alongside Spain and Portugal—which is why the Portuguese see themselves in a power struggle with the church and are asserting their power in return. Similarly, the allegedly “Catholic” governor, Don Cabeza, exhibits a racialized ideology that shows no signs of discipline by a Christian imagination. And so the inevitable happens: the cardinal, ambassador for the papacy, effectively sanctions a military operation that will end with the slaughter of the Guaraní and the Jesuits who remained in solidarity with them. Rodrigo dies with his sword in his hand; Father Gabriel is shot while carrying the Host.26

What we witness is an example of liturgical capture: for the powers-that-be, whether from Spain, Portugal, or the papacy, the rites of the church have been co-opted by a rival story. Their performance is bastardized, their enactment compromised because they have been repositioned within a story and mythology that guts their kingdom orientation. When the Spanish and Portuguese authorities assemble their armies for the oncoming slaughter, we hear a prayer that has become an utter parody: Dominus vobiscum, “The Lord be with you.” So, too, they have become hoodwinked by a market logic. When the cardinal receives the report of the slaughter and asks whether it was really necessary, Don Cabeza’s stunted commercial imagination answers in the affirmative: “I did what I had to do given the legitimate purpose which you sanctioned.” Don Hontar distills the lie of this “tragic” logic: “You had no alternative, your eminence. We must work in the world. The world is thus.”

But the cardinal, complicit as he is, also refuses to buy this logic: “No, Senhor Hontar. Thus have we made the world. Thus have I made it.”

Case Study 2: Liturgies of Violence in Rwanda

We are trying to face head-on one of the most trenchant critiques of the Cultural Liturgies project, what we’re calling “the Godfather problem”: How can we claim that worship uniquely forms a “peculiar people” when there seems to be so much evidence of people who have been immersed in the church’s liturgies yet exhibit “worldly” ways? Or why should we imagine the church’s worship forms us as a distinct polis when Christians immersed in such rituals so often exhibit the same “earthly city” politics as the world? We are submitting ourselves to the reality check of case studies as an antidote to ecclesiological idealism. That includes facing up to cases where the church has not only failed to resist but actually fomented injustice—what Jennings names “ecclesial failure.”

In his dense study A Brutal Unity, Ephraim Radner puts the church’s own ugliness before us and proposes a counterintuitive thesis: if you care about justice and the common good, you should care about the church. Exhibit A in his argument is a very stark one: Rwanda. This case study emerges in the context of Radner’s critique of William Cavanaugh’s argument in The Myth of Religious Violence.27 Responding to Hitchens-like claims that religion causes violence, Cavanaugh argued that, in fact, it was the politics of statecraft that really generated the so-called Wars of Religion in Europe, for example. In that sense, contrary to liberal and secularist “myths” that blamed such violence on religious belief, Cavanaugh argued that the liberal state generated such violence. And it was just to the extent that Christianity assimilated itself to the liberal nation-state that it became embroiled in such violence. If the church retained its identity as “the church,” Christianity wouldn’t have been implicated in such violence. You can see a working hypothesis about the relationship between church and state at work behind this argument—a model that we might describe as loosely “Hauerwasian.”28

Whatever explanatory power Cavanaugh’s account might have for a European context, Radner says, the fact is there is just no way to excuse the church from violence in a context like Rwanda.29 While not a “sole” cause (contra the New Atheist thesis), the fact is that the church—and specifically “intra-Christian competition”—contributed to violence in the Rwandan genocide.30 As Radner asks, “Given that Christians did the killing and did so surrounded by their lived Christian symbols and spatial forms and led often by their Christian pastors, in some cases taking Mass quite self-consciously before going out to kill, how are we to understand the nature of their faith?”31

Rwanda, in other words, is the countervailing exemplar to the oft-celebrated French village of Le Chambon.32 The church in Rwanda is not the hero; it is a creator of villains. “We must seek to identify the Church first of all as a killer,” Radner argues, “if we are to understand the nature of ecclesial existence properly” (BU, 19–20).33 If some have invoked the formative power of Christian practices to make sense of how a Protestant village in France was moved to undertake the risk of sheltering Jewish neighbors and strangers from the Nazis, what do we make of those same practices functioning as the prelude to genocide? It won’t do to simply attribute the violence to nonreligious factors of ethnic identity fomented by postcolonial policy.

Christianity simply stares one in the face in Rwanda’s modern history: the historian must account for its presence, character, and action as a matter of objective understanding. The pervasiveness of Christian forms within Rwandan society—churches everywhere, priests and pastors and the religious integrated into the quotidian as well as elite structures of society at every point—made possible, at least on some basic ordering of public space, the fact that more people were killed during the genocide in church buildings than perhaps anywhere else.34 How and why did the bodies end up there and murder happen there, such that today the most numerous and chilling memorials to the genocide are churches filled with the bones and skulls of victims slaughtered among the pews and before the altars? (BU, 30–31)

How can we make claims about the formative power of liturgy—the way a visual and sonic environment sanctifies perception and restor(i)es the imagination—when these rites not only did nothing to prevent this genocide but in fact were caught up as contributors to it? At stake here is not just a particular theological agenda but the integrity of the gospel and sacramental nature of the church. Facing up to this question does not preclude appreciation of the complexity and nuance of factors involved. Following Longman, Radner points out the contingent history of interweavings not unlike those diagnosed by Willie Jennings. A long missionary history (that focused on emerging leaders among the Batutsi) is intertwined with the reality of Protestant versus Catholic “religious competition,” creating divisions that were exploited by Rwandan ruling forces. Furthermore, the necessary work of translation and contextualization also enshrined and sacralized some existing political realities and divisions, often unwittingly. So “when push came to shove, the Church herself had constituted sacred power along constructed and deeply divisive ethnic lines, ones that she bequeathed to the emerging sphere of civil-political governance” (BU, 34).35 In ways parallel to the case of New World slavery, in Rwanda the church was not so much trumped by racial politics as responsible for it. “In the case of Rwanda,” Radner concludes, “it is not possible to overestimate the formative and enabling power of these religiously grounded conceptualities and their origins” (BU, 37).

If Christians are responsible for violence, if the conceptions of their motives are given in Christian terms, if these conceptions have been shaped and gathered together in their hostile force through particular decisions made on behalf of Christianity’s ecclesial vocation, so understood, and if, finally, these decisions and their forms can be shown as bearing the power of violence, it is appropriate . . . to speak of a specifically Christian responsibility for violence, one . . . that must fill every onlooking Christian with “anguish” because of its religious import. (BU, 37–38)

The faithful response here is not to rush to a defense, to an explanation, to deflect the force of this anguish. This anguish is something to be entered, a kind of interrogation room in which we need to dwell, feeling the hot light of the question.

Radner’s disturbing question demands an account, if not quite a defense. And Radner provides some resources for diagnosis—not to excuse the church but rather, Nathan-like, to confront it with the depth of the question. In some significant sense, he argues, the propensity for the church to contribute to such unjust social and political realities stems from the lamentable reality of denominational division and “ecclesial competition” (very much against Jesus’s prayer in John 17): “A divided Church simply magnifies political contests, that is, the violent contestability of human life in general. It is also incapable of forming resisting—redemptive—communities of a particular character; that is, of forgiveness, reconciliation, and sacrifice” (BU, 73–74).36 In the case of Rwanda, this ecclesial competition tracked back to missionary competition: “The competitive missionary spheres, making use of longstanding antagonistic rhetoric now inflated by local political and social wrestling, ended up by teaching church members distinctions and antipathies that were informed by specifically salvific claims” (BU, 70). In terms we’ve used above, penultimate differences were invested with ultimacy; the language of ultimacy was marshaled as a motivator for penultimate political realities. The line, in short, was blurred. “Divide and conquer” as a missionary strategy became the horrific Tutsi-Hutu divide of the genocide. And it’s not just that liturgy didn’t prevent this; it seems to have contributed to the horror.

Examples of such tragic “ecclesial failure” could, of course, be multiplied—“German Christianity” under National Socialism; apartheid in the Dutch Reformed Church of South Africa; the treatment of First Nations peoples in Anglican residential schools; and, sadly, many more. How can we account for the inadequacy, even exacerbation, of liturgy in these cases, given the sorts of claims we’ve been making about liturgical formation? Do these cases disprove such claims?

What if liturgical formation is both the problem and the solution? What if these tragic cases both challenge and confirm our thesis?

Analyzing Ecclesial Failure

Brian Bantum’s consideration of race suggests the complexity of the challenge. Like Jennings, Bantum rightly points out all the ways the church’s worship licensed racialization and racism. Particularly harrowing is the antebellum baptismal rite of confession for slaves recorded by Francis La Jau, an Anglican bishop from colonial South Carolina: “You declare in the Presence of God and before this Congregation that you do not ask for the holy baptism out of any design to free yourself from the Duty and Obedience you owe to your Master while you live, but merely for the good of Your Soul and to Partake of the Graces and Blessings promised to the Members of the Church of Jesus Christ.”37 Bantum points out the heinous domestication of the baptismal rite at work here: “The presence of God was invoked, not as an entrance into a new kind of community, but in order to concretize one’s participation in a racialized community.” Rather than signaling the radical reorientation of an upside-down kingdom and initiation into the politics of the city of God, the baptismal moment only reinforces the status quo. Indeed, it becomes “a moment of profound cultural encounter where the meaning of blackness and whiteness are arbitrated through the language of baptism. . . . Here the church, as well as the presence of God, are but tools that fortify a reality far deeper and more profound than God and the church—race.”38 The religious liturgy has been marshaled for the reinforcement of another social imaginary. “Even the explicitly religious has been co-opted by a reality that is understood to be prior and primary,” Bantum comments. And that trumping reality is “the telos of white life.”39

The disturbing insight of Bantum’s work highlights how racialized formation is its own kind of perverted discipleship, a social imaginary we absorb not only from “secular” liturgies but from misdirected, co-opted Christian worship as well. Thus he presses us to see race “as a religious modality” and our assimilation to racist imaginaries as a kind of liturgical deformation.

Racial identity constitutes a form of discipleship that must be theologically accounted for and resisted. That racial performance exists as a social phenomenon is certainly a challenge to Christian discipleship. But to suggest it is a religiously grounded form of being in the world is to infer a theological response that must be more precise in its description of the problem and the way forward. Racial performance is not simply a sinful behavior that must be avoided, but a way of being in the world that is more than difficult to resist, for it is the air we breathe.40

This is why the way forward begins with a forthright stock-taking of our deformation, which is itself a prelude to repentance. “To imagine a life in Christ,” Bantum counsels, “we must begin to reimagine the shape of our unfaithfulness, our complicity in the economy of race, in order to faithfully imagine what it might mean to participate in the renunciation of an old life marked by the tragedy and violence of race.”41

And yet, while Bantum doesn’t flinch from diagnosing the depth of our complicity, the answer to such perverted racial discipleship is the counter-formative power of discipleship in Christ. “The possibility of imagining discipleship in a racial world must begin with Jesus. To imagine a life of discipleship, a way of being in the world that disrupts racial logic and formation, the church must begin to look anew at the center of our faith”—Jesus, the mulatto, hybrid God-man.42 “The possibility of our renunciation of a discipleship inflected by race only becomes possible by entering into the body and life of another.”43 And so, while Bantum points out how the rites of baptism could be co-opted, he also points to baptism as the way we are reborn: “Baptism is entrance into the work of Christ’s person. It is the initiation into his body and his people. As such, this entrance marks the renunciation of the world’s claims upon the baptized as well as the renewal, or rebirth, of the person. It is an entrance that requires a departure from the racial economy of the West and its children. To be baptized is to enter into Christ’s mulattic personhood and an economy of negotiation that such a presence is necessarily bound to.”44

Baptism is not a magical solution. It is the beginning of this “negotiation”; it “draws us into a drama of God’s presence in the world,” calling us to a “mulatto/a Christian existence” that comprises “the negotiation of identity inherent in our claim to be ‘in Christ.’”45 Liberation from myths of “purity” might be the beginning of wisdom for grappling with questions of deformation and sanctification.

Ecclesiology and Ethnography

Locating the Church

What characterizes the work of Jennings, Radner, and Bantum is a theologically motivated accountability to empirical realities, disciplining the claims of liturgical formation and ecclesial identity with the realities of our compromise and complicity. Thus their work can be seen as part of a wider conversation at the intersection of ecclesiology and ethnography.46 Unlike other paradigms of encounter between theology and social science—in which social science is taken to be the neutral arbiter and “objective” assessor of theological claims47—the emerging conversation between ecclesiology and ethnography appropriates the methods and practices of social description from a confessedly theological center, and with a primarily theological interest. As John Swinton has remarked, “If the church’s task is to bear witness in the ways Hauerwas suggests, then the need to explore the empirical church is of great importance, not for sociological purposes but for theological reasons.”48 There is no witness that isn’t empirical; otherwise we’re on the road to gnosticism. Insofar as witness is embodied, and the church is Christ’s body, all of our ecclesiological claims are de jure “exposed,” in a sense, to empirical assessment. Any claim about the formative power of the church’s worship is, by nature, falsifiable even if the operations of the Spirit are not subject to merely natural assessment. Nonetheless, “by their fruits you shall know them.”

Christian Scharen penned something of a manifesto for theology’s need of ethnography just over a decade ago. The catalyst was John Milbank’s rather grandiose claims about “the Church” in his landmark work Theology and Social Theory.49 Responding to critiques that his account of the church was too idealized, Milbank conceded that there remained an important role for “judicious narratives of ecclesial happenings which would alone indicate the shape of the Church that we desire.”50 Here Scharen sees an argument for ethnography as ecclesiology—not evacuating theology into social science but appreciating the theological import of attending to the embodied shape of actual congregations and parishes.51 Theologians, he says, need to “be better students of the real.”52

And herein lies the accountability and challenge. Despite claims about the church as a “contrast society,” an “alternative polis,” an outpost of the city of God, it turns out that when you simply attend to the exhibited lives of congregations and congregants, “actual church people look rather a lot like everybody else.”53 For Scharen, what’s needed is “a means to account directly for cultural pluralism and the complicated, bifurcated social-structural worlds shaped by and shaping Christian people and their communities.”54 Without a sufficiently complex analysis and account, “one may miss the ways real communities of faith are Christian in ways that tightly interrelate with . . . their congregational ‘communal identity.’ Without this more complex understanding of culture and community, it is difficult to account for the identity ‘given’ through eucharistic participation, never ‘generic’ but always particularly incarnate within the life of this or that Christian community.”55 In other words, an idealistic ecclesiology that fails to attend ethnographically to the nitty-gritty sociological realities of competing formation will, ironically, be unable to properly recognize and diagnose the dynamics of the church’s assimilation. Simplistic, grand claims about the church as “anti-world” will miss the ways churchgoers are shaped by “the world.”56 As Scharen puts it, “Sociologically uninformed dichotomies between the church and the world, because of the simplistic and holistic understanding of culture implied, really harm their own efforts better to lead the church in being the church exactly because their crude cultural lens cannot see exactly the ways in which they are bound up with the world in their very ways of being the church.”57

Ethnographic attention to the dynamics of cultural formation is not only a strategy to diagnose deformation; it also becomes a way to (1) affirm positive interplay between “public” and “ecclesial” liturgies, attuned to listen and look for the work of the Spirit beyond the church,58 and (2) help distill and highlight those effects of formation that can be more specifically attributed to congregational life and immersion in worship. If we are going to be able to see the effects of virtue formation, we need to consider a multiplicity of formative factors in the lives of congregations and Christians. “If the church is a community ‘shaped by Jesus’ as Stanley Hauerwas claims, or constituted as ‘the other city’ as Milbank claims, then what constitutes such an identity? Since the members not only worship God together in particular churches but also are involved in many other spheres of social life, such claims beg for a context in order to make sense. And it will not do simply to roll out church-world distinctions; in so many ways the church is ‘worldly’ even in so far as it serves as a counter society.”59

What I find refreshing and promising about this conversation is its refusal of reductionism without floating off into aspirational idealism. As Luke Bretherton summarizes it, “The broader point to draw for the relationship between ethnography, ecclesiology, and political theory is that the church cannot be read as simply a microcosm of broader political processes and structural forces: it has its own integrity. Yet neither can an analysis of the church be separated from how it is in a relationship of codetermination (and at times co-construction) with its political environment.”60 That seems just right to me: an antireductionism vis-à-vis sociology, an antignosticism vis-à-vis theology.

Ultimately, ecclesiology as ethnography is a set of disciplines for paying attention to the lived reality of our congregations, diagnosing our betweenness, our hybridity, but also our complicity and compromise. This is crucial in addressing “the Godfather problem” because it is the only way we will be able to identify the functional theologies that trump the official theologies of our churches and congregations.61 In other words, sociologists might be able to detect (performative) heresies that theologians would miss.

Picturing Conflictedness:

Identity in the Colonies

While the church is—and is called to be—distinct, peculiar, called-out (ek-klēsia), it is not called to retreat, withdraw, or huddle into an enclave. The New Testament epistles are addressed to a “peculiar people” who are in the midst of the world, embedded in the contested territory of creation that in the meantime we call the saeculum. The call to follow Christ, the call to desire his kingdom, does not simplify our lives by segregating us in some “pure” space; to the contrary, the call to bear Christ’s image complicates our lives because it comes to us in the midst of our environments without releasing us from them. The call to discipleship complicates our lives precisely because it introduces a tension that will only be resolved eschatologically.

Daniel Mendelsohn’s memoir, The Elusive Embrace, provides insight into what this sort of tension feels like.62 Actually, to describe the book as a memoir is already too simplifying. The essay is part memoir, part intellectual history, and part literary criticism in which Mendelsohn draws on his classical scholarship to illuminate his experience as a Jewish gay man with a passion for the Greeks and classical culture, emerging into a self-understanding of this identity and then figuring out how to navigate what that means. It can be read as an analogy, even an allegory, of what it means to embrace one’s Christian identity.

Most germane in this context is his reflection on two tiny particles in Greek: men and de. Grammatically these particles function in a couplet to signal “on the one hand” and “on the other hand.” “What is interesting about this peculiarity of Greek, though, is that the men . . . de sequence is not always necessarily oppositional. Sometimes—often—it can merely link two notions or quantities or names, connecting rather than separating, multiplying rather than dividing. . . . Inherent in this language, then, is an acknowledgement of the rich conflictedness of things.”63 It is this conflictedness that should interest us here as we think about the realities of (de)formation and the church’s embeddedness in the world.

Mendelsohn sees this kind of men . . . de conflictedness in his own experience but also where he lives. Chelsea is often described as a gay “ghetto” in New York City, but Mendelsohn resists that description. Unlike, say, the Castro in San Francisco, which, like the shtetls of Poland, was a ghetto made necessary by oppression and exclusion, Chelsea, he points out, has a very different history. “Chelsea came into being in the mid-1980s not as a safe haven in which gay men might take shelter” but instead as a neighborhood renewed and gentrified by an influx of citizens with the freedom to live according to their identity. And so, Mendelsohn emphasizes, the analogy for Chelsea isn’t medieval Jewish ghettos but rather the colonies of the Greek city-states. “‘Colony’ is a word that was to acquire its own evil history, of course; but it began fairly innocuously. The restless body-loving Greeks solved their own perennial overpopulation problems by sending out their more vigorous citizens to settle hitherto unknown outposts of the map. They called these places apoikiai, ‘away-from-homes.’ The colony is a place to be associated with expansion and, hence, success—as opposed to the ghetto, which we associate with oppression and compression and, eventually, death.”64

But, of course, Chelsea is not a colony across the Mediterranean/Hudson in some distant land—it is a “colony” in the thick of Manhattan (and now prone to be gobbled up by innumerable bobos). And yet it is on the edge; its center is on the edge of the dominant city’s makeup and habits and expectations. It is a men . . . de sort of place. And so this topos is also a paradox: “para, against, doxa, expectation.” “What else do you call a place,” Mendelsohn asks, “that must somehow be both an edge and a center, somewhere you could simultaneously feel utterly different, as you knew you were, yet wholly normal, as you wanted to be?”65 But it also means such a place is unstable, conflicted, a place where one lives but perhaps without ever feeling settled (“the place hovers between identities”). “To me,” he admits, “wandering as I do between the two geographies of my own life, the most interesting and yet always suspect topos in the ongoing debate about gay culture and identity is that there is such a thing as ‘gay identity’ at all.”66 If there is an “identity” here—and Mendelsohn is skeptical—it is bound up with a men . . . de conflictedness, a hybridity and betweenness that doesn’t mean one lacks identity but, in fact, has assumed it. (“All Americans,” Mendelsohn remarks, “are, in the end, inauthentic, something else, something multiple and hybrid.”)67

And yet: “This is the place where I decided to live,” Mendelsohn concludes, “the place of paradox and hybrids. The place that, in the moment of choosing it, taught me that wherever I am is the wrong place for half of me.”68

The engagement between ecclesiology and ethnography is nothing if not a call for the church to be honest about its conflictedness, its hybridity, its contested formation and identities. The church is not unlike Chelsea, both an edge and a center, and to be “in Christ” in the saeculum is to inhabit a paradoxical place.

The Pastor as Ethnographer: Cultural Exegesis of the Rites of Empire

When we appreciate the significance of ethnography for critical, even prophetic service to the body of Christ, perhaps in the context of a congregation’s worship we might imagine the pastor as a political theologian.69 And the first task of the pastor as political theologian is to serve a congregation by being an ethnographer of the rites of the empire that surround it, teaching it to read the rituals of late modern democracy through a biblical, theological lens.

As we discussed in chapter 1, the “political” is not just the administration of law—as if political life boiled down to trash-removal service, keeping the traffic lights operational, and policing legal obligations. The “political” is not merely procedural; it is formative. The polis is a koinōnia that is animated by a vision of the good. And while Aristotle couldn’t imagine competing visions of the good within the walled city’s territory, this reality of competing poleis and rival goods was something early Christians appreciated from the beginning. There are rival poleis within the confines of the nation-state. The formative power of the polis is not embodied in its sword but in its rituals. In this respect, the polis’s vision of the good life is carried in all kinds of nonstate rhythms and routines that reinforce, say, the libido dominandi of the earthly city, or the ultimate mythology of independence and autonomy that is not only articulated in a constitution but enshrined in a million microliturgies that reinforce our egoism.

So part of the role of the pastor as political theologian is apocalyptic: to unveil and unmask the idolatrous pretensions of the polis that can be all too easily missed since they constitute the status quo wallpaper of our everyday environment.70 It requires thoughtful, rigorous, theological work to pierce through the everyday rituals we go through on autopilot and see them for what they are: ways we are lulled into paying homage to rival kings. This requires what Richard Bauckham calls a “purging of the Christian imagination.”71 At stake here is nothing less than true versus false worship.72

So part of the pastor-theologian’s political work is to enable the people of God to “read” the practices of the regnant polis, to exegete the liturgies of the earthly city in which we are immersed. This is an essentially local, contextualized task, both in time and in space: the political idolatries that tempt us and threaten to deform us are localized. The political hubris of today is not the same as the political hubris of even eighty years ago, let alone of fifth-century Africa or sixteenth-century New England. Such cultural exegesis has to be local and contextual, but it also has to be theological (and, as I’ve argued, theologically sociological). If you want to deepen the theological capacity of the church, try offering a theological ethnography of Independence Day (which, admittedly, might also be a good way to shrink a church).

We can see ancient exemplars of this. A standout is a sermon Augustine preached on New Year’s Day in 404 (likely in Carthage), in which he offers a theological and cultural exegesis of the pagan festivals that would dominate the city that day.73 (This might also explain why his sermon was three hours long, a kind of filibuster to keep his parishioners away from the temptations as long as he could.)74 He takes as his text a line they’ve just sung from Psalm 106: “Save us, Lord our God, and gather us from among the nations, that we may confess your holy name” (v. 47). How do you know if you’re “gathered from among the nations”? Augustine asks. “If the festival of the nations which is taking place today in the joys of the world and the flesh, with the din of silly and disgraceful songs, with the celebration of this false feast day—if the things the Gentiles are doing today do not meet with your approval” (198.1) . . . well, then you’re gathered from the nations.

But this isn’t just pietistic moralizing. Augustine launches into a theological and philosophical analysis of the rites of pagan feasts. At stake, he argues, are faith, hope, and love:

If you believe, hope, and love, it doesn’t mean that you are immediately declared safe and sound and saved. It makes a difference, you see, what you believe, what you hope for, what you love. Nobody in fact can live any style of life without those three sentiments of the soul, of believing, hoping, loving. If you don’t believe what the nations believe, and don’t hope for what the nations hope for, and don’t love what the nations love, then you are gathered from among the nations. And don’t let your being physically mixed up with them alarm you, when there is such a wide separation of minds. What after all could be so widely separated as that they believe demons are gods, you on the other hand believe in the God who is the true God? . . . So if you believe something different from them, hope for something different, love something different, you should prove it by your life, demonstrate it by your actions. (198.2)

The remainder of Augustine’s sermon is a sustained cultural exegesis that aims to make explicit the (pagan) faith, hope, and love that is “carried” in the city’s feasts and rituals, which too many of his parishioners merely considered “things to do” rather than rites that do something to them. The burden of Augustine’s theological analysis is to highlight the incoherence of both singing the psalm and participating in the festivals.

This is an ongoing task. One of the responsibilities of the pastor as political theologian, then, is to help the people of God “read” the festivals of their own polis, whether the annual militarized Thanksgiving festivals that feature gladiators from Dallas or the rituals of mutual display and haughty purity that suffuse online regions of “social justice.” Our politics is never merely electoral. The polis doesn’t just rear to life on the first Tuesday of November. Elections are not liturgies; they are events. The politics of the earthly city is carried in a web of rituals strung between one occasional ballot box and the next. Good political theology pierces through this, unveils it—not to help the people of God withdraw but to equip them to be sent into the thick of it. When we are centered in the formative rites of the city of God, Augustine reminds his hearers, “even if you go out and mix with them in general social intercourse . . . you will remain gathered from among the Gentiles, wherever you may actually be” (198.7).

This points to the second, constructive function of the pastor as political theologian. It is not sufficient to unmask the rites of earthly city politics. We also need to help the people of God cultivate their heavenly citizenship. Citizenship is not just a status or a property that one holds; it is a calling and a vocation. I can hold a Canadian passport and a Canadian birth certificate and yet fail to be a good Canadian citizen. Citizenship is not only a right; it is also a virtue to be cultivated. The pastor as political theologian plays a role in shepherding civic virtue in citizens of the city of God (cf. Phil. 3:20).75

If Christian worship constitutes the civics of the city of God, then liturgical catechesis is the theological exercise by which we come to understand our heavenly citizenship. In other words, a key theological work that is charged with political significance is to help the people of God understand why we do what we do when we worship. Liturgical theology is political theology. Cultural exegesis of Christian worship makes explicit the political vision that is “carried” in our liturgy. The pastor-theologian has responsibility to unpack the telos, the substantive, biblical vision of the good, that is implicit in Christian worship.76

Picturing Political Discipleship:

Epistles to a Governor

The pastor as political theologian—actually, every pastor—is a pastor not only of the gathered church but also of the sent church. In Abraham Kuyper’s terms, the pastor is called to shepherd not only the church as institute but also the church as organism. The pastor-theologian shepherds the work of citizens of the city of God who answer the call to enter the messy permixtum of the saeculum.

We can see a case study of this role in Augustine’s ongoing relationship with Boniface. Boniface was a Roman general and African governor. In their ongoing correspondence we see a spiritual friendship in which Augustine the pastor-theologian is not afraid to challenge and exhort the imperial soldier. But we also see a political practitioner who is hungry for theological wisdom, and not merely blessing or permission. In fact, Boniface was the recipient of a long, intricate theological letter about the Donatists (letter 185) that Augustine later, in his Retractationes, described as a book (The Correction of the Donatists). After this lengthy letter, Augustine sent Boniface a short, simple note: “It is highly pleasing to me that amid your civic duties you do not neglect also to show concern for religion and desire that people found in separation and division be called back to the path of salvation and peace.”77

In Letter 189, Augustine dashes off an eloquent articulation of the faith fused with theological counsel in response to a pressing request from Boniface for help (189.1). Augustine begins where he always does: with love. “This, then, I can say briefly: Love the Lord your God with your whole heart and with your whole soul and with your whole strength, and Love your neighbor as yourself. For this is the word that the Lord has shortened upon the earth [alluding to Rom. 9:28].” He exhorts Boniface to “make progress” in this love by prayer and good works, bringing to fullness the love that has been shed abroad in our hearts (189.2). For it is “by this love,” Augustine reminds him, that “all our holy forefathers, the patriarchs, prophets, and apostles pleased God. By this love all true martyrs fought against the devil to the point of shedding their blood, and because this love neither grew cold nor gave out in them, they conquered.” And it is the same love that is at work in Boniface, Augustine points out: “By this love all good believers daily make progress, desiring not to come to a kingdom of mortal beings but to the kingdom of heaven” (189.3).

Augustine then speaks directly to some of Boniface’s doubts and questions: “Do not suppose that no one can please God who as a soldier carries the weapons of war” (189.4). Look at the examples: “Holy David,” the centurion who displayed great faith, the prayerful Cornelius who welcomed Peter, and others. These are exemplars for Boniface to emulate. But Augustine also offers vocational wisdom that is rooted in some fine points of eschatology. While some are called to lives of chastity and perfect continence and cloistered devotion, “each person, as the apostle says, has his own gift from God, one this gift, another that (1 Cor. 7:7). Hence others fight invisible enemies by praying for you; you struggle against visible barbarians by fighting for them.” While we might long for the day when neither sort of battle is necessary—neither prayer warriors nor weaponized soldiers—we need a more nuanced eschatology, Augustine counsels. “Because in this world it is necessary that the citizens of the kingdom of heaven suffer temptation among those who are in error and are wicked so that they may be exercised and put to the test like gold in a furnace,” Augustine says, “we ought not to want to live ahead of time with only the saints and the righteous” (189.5). Don’t think we can “live ahead of time” is Augustine’s way of saying: don’t fall for the temptation of a realized eschatology.

So answer your call, Boniface, but take up your vocation in ways that are faithful, in a way that longs for kingdom come without thinking you can make it arrive. “Be, therefore, a peacemaker even in war in order that by conquering you might bring to the benefit of peace those whom you fight” (189.6). As he begins to draw the letter to a close, Augustine seems attentive to the unique temptations the soldier faces, attuned to the cultural liturgies of military life: “Let marital chastity adorn your conduct; let sobriety and frugality adorn it as well. For it is very shameful that lust conquer a man who is not conquered by another man and that he who is not conquered by the sword is overcome by wine” (189.7). He closes with an exercise in liturgical catechesis. Appealing to the Preface of the Mass (“Lift up your hearts” / “We lift them up to the Lord”), Augustine encourages Boniface to find in that a posture for life, for his work and vocation: “And, of course, when we hear that we should lift up our heart, we ought to respond truthfully what you know that we respond” (189.7). In other words, don’t just say “we lift up our hearts”—lift up your heart in your work.

Augustine’s affection for Boniface did not preclude admonishment. Letter 220 is an intriguing case. After the death of his wife, Boniface seems to be lost. He seems to be wavering in his sense of calling as a soldier and imperial servant, but he also seems wayward in his grief, making bad decisions. When they had last seen each other in Hippo, Augustine was so depleted by exhaustion he could barely speak. And so he follows up with a letter, by which he intends, he says, “to do with you what I ought to do with a man I love greatly in Christ.”78

After the death of his wife, Boniface wanted to abandon his public life and retreat to a monastery to devote himself to “holy leisure.” But when he expressed this to Augustine and Alypius in private, they counseled otherwise. “What held you back from doing this,” Augustine reminds him, “except that you considered, when we pointed it out, how much what you were doing was benefitting the churches of Christ? You were acting with this intention alone, namely, that they might lead a quiet and tranquil life, as the apostle says, in all piety and chastity (1 Tim. 2:2), defended from the attacks of the barbarians” (220.3). These pastor-theologians exhorted him to remain steadfast in his public life; indeed, in some ways their pastoral/theological work depended on his public work as governor and defender.

Though Boniface continued to answer the call to public office, the weakness of grief seemed to compromise his moral judgment, and thus Augustine confronts him for abandoning continence, for being “conquered by concupiscence” (220.4), and for becoming embroiled in webs of intrigue. Augustine forthrightly reminds him of the need for repentance and penance. And then Augustine the pastor-theologian presses Boniface theologically to be more resolute in the execution of his public duties. “What am I to say about the plundering of Africa that the African barbarians carry out with no opposition, while you are tied up in your difficulties and make no arrangement by which this disaster might be averted?” (220.7). While Boniface is trying to secure his status in a contested imperial court, he is in fact shirking his duties to the common good (see: election season). “Who would have believed,” Augustine asks,