5 Does heterodox economics need a unified crisis theory?

From profit-squeeze to the global liquidity meltdown

Gary A. Dymski

Introduction

This chapter makes two abstract theoretical arguments and one empirical one. The first theoretical claim advanced here concerns the nature of heterodoxy in economics. All economic theories define both the primary actors and forces that constitute any society’s economic relations, and propose some vision of the successful reproduction of these relations. Usually successful reproduction is equated with stable growth. Some theories embed the assumption that if a given set of economic relations can achieve stability or balance, it can, if left undisturbed, sustain stable growth. Other theories embed the assumption that the possible breakdown of stable growth is endogenous: a crisis in reproduction is immanent in the very nature of economic relations. This distinction—the exogeneity or endogeneity of the possibility of crisis—defines the difference between heterodox and orthodox approaches to economic theory.

The second theoretical claim advanced here is that heterodox theories are more robust when they encompass the possibility that stable growth can be undermined, and crisis can emerge, for different reasons. A multidimensional approach, which encompasses several possible avenues in which economic relations can break down, is contrasted here with unicausal approaches in general and, in particular, Minsky’s single factor crisis mechanism.

An empirical argument is then made, using a stylized rendering of aggregate US empirical evidence. Specifically, it is shown that Minsky’s ideas about what causes crisis, and about what policy measures can overcome crises, are largely consistent with these data through 1980; but after 1980, his specific theoretical/ policy approach are inconsistent with the data. Minsky remains a protean figure in heterodox theory because he insists so strongly that instability will invariably emerge from stability—a lesson that non-heterodox thinkers never seem to learn. But a multifaceted approach provides a surer framework for understanding the trajectory of lived crises, from the profit-squeeze episodes of the 1960s and 1970s to the global liquidity meltdown of the present day.

What is heterodox economic theory?

Many economists have dissented from the strictures on theorizing implicit in orthodox economic theory since the latter theory took shape in the writings of Walras, Jevons and Marshall. What these economists have shared is dissatisfaction with the critical assertion of the orthodox approach: the insistence that autonomous market forces tend to lead the economy to an equilibrium that cannot be improved by government policy interventions.

A question that has persisted throughout the century or more that heterodox thinking has gathered force is this: what defines or binds those who dissent from the orthodox—the “mainstream”? Heterodoxy and orthodoxy in any theoretical field exist in dialog. Orthodoxy authorizes certain methods and ideas and then polices their boundaries. A heterodoxy develops alternative methods and ideas to reach conclusions that are ruled out under orthodox constraints.

In the field of economics, orthodox macroeconomic theory crafted its vision of smooth, undisturbed economic growth precisely by discarding central ideas of some of its principal historical forebears—Marx, Keynes and Schumpeter. These theorists all build on the idea that emphasize endogenous forces would eventually undermine any period of economic growth. But this is precisely what was abandoned in neoclassical theory. A satisfactory demonstration that a decentralized “general” equilibrium could be achieved by agents interacting in markets—the avatar of the orthodox approach, achieved by Debreu (1959)–was possible only if time and ignorance, as well as power, were eliminated from consideration in advance. Introducing time means allowing both for the fact that some economic processes require the passage of time, and for the fact that everything doesn’t happen at once. Ignorance refers to the inability of agents in any economic setting to comprehend what is happening, or what might happen; of special importance is uncertainty—that is, agents’ inability to predict future events with complete confidence, no matter how much historical data they possess. Power, in turn, is exerted in an economic setting when one agent can use some advantage—larger size, threat of force or superior liquidity—to extract additional rent or effort from another.

Removing power permits economists to abstract from the social processes that underlie and construct market relations, and from the social consequences of economic processes. Removing time and ignorance eliminates examination of agents whose economic roles require them to make decisions in real time, based on conventional beliefs about their future prospects, which they hold with greater or less degrees of confidence. That is, this step removes any consideration that expectations about future events are fragile, and based on understandings that can change violently when circumstances change.1

So once time, ignorance and power are eliminated, one can then build economic models in which well-behaved, fully informed agents make choices based on their own net individual gain from any sequence of transactions. The terrain of orthodox theory has broadened considerably from the timeless, once-and-for-forever market framework that was used to demonstrate the existence of decentralized equilibrium itself. Orthodox theory now incorporates many varieties of game-theoretic and dynamical models, which respectively envision sequences of moves among interacting agents and sequences of choices across time. The equilibria that can be achieved in these more open frameworks are weaker, and often non-unique. However, a distinctive orthodox approach persists, in that the emphasis remains on how sustainable equilibria can be sustained in these thicker interactional or longer-term settings. And while the tools of utility maximization and equilibrium market exchange are being applied to ever more diverse social settings—leading to the creation of a contemporary field of “political economy” that has usurped a term formerly associated exclusively with the classical tradition of Smith, Ricardo and Marx. This new “political economy” remains orthodox in that it explains why the social or political phenomena analyzed—ranging from government policy choices, to election outcomes, to laws about abortion or adoption—can be explained as the result of a well-formed calculation of self-interest by the agents involved, given their information sets, endowments and preferences. That is, emphasis remains on how a given event could arise and persist as a result of a consensual process.2

A different type of unifying thread runs through heterodox theory: an insistence that economic systems contain within themselves the possibility of disruptures—of crises of reproduction and growth. The theories embodying this approach have different substantive foci—some center on the impact and consequences of power relations, some on uncertainty, and some on firm strategies. But in every case, these investigations identify structural elements within the economy that create ruptures. These ruptures—that is, serious disruptions in the overall capacity of capitalist economies to increase aggregate income levels and generate profit and interest for owners of firms and of assets—can be described as crises.

So whereas orthodox theory seeks to characterize the movement of the capitalist economy through time as a harmonious dynamic of equilibrium market exchanges, heterodox theory centers on the fragility and unsustainability of growth trajectories. Thus, heterodox economics cannot be accurately labeled an anti-doctrine, nor can it be reduced to a curiosum of special-case parameters in equilibrium models.3 Rather, heterodox macroeconomic theory has arisen and persisted as a terrain of inquiry precisely because of its preoccupation with the problem of crisis. So heterodox economic theory doesn’t just need a crisis theory: it is crisis theory.

One critical flaw or many?

For many years, heterodox economists have divided into schools of thought based on the flaws they have identified in capitalist dynamics and, in turn, in orthodox theory. Some have turned to Keynes and his vision of how uncertainty undermines belief and convention in unstable market settings; some turn to Kalecki and his vision of how conflict over distribution undermines capitalist dynamics; some turn to Marx and his focus on conflict at the point of production, or on secular long-term forces that gradually constrict the rate of profit.

This is where divisions emerge in heterodox economic theory. Capitalist economic growth can rupture in several different ways; and the theoretical basis for these different breakdown mechanisms is associated with different foundational figures—Marx, Keynes, Kalecki, Schumpeter and so on. So heterodox theorists differ over whether there is one primary flaw in economic reproduction mechanisms, or many. Some build on one foundational figure, others on several. This means that there are as many substantive controversies between heterodox theorists as between heterodox and orthodox theorists.

Heterodox economics is best served when it allows for different forms of crisis and is open to the insights of multiple foundational figures. If the point is to understand how crises can arise, then frameworks that encompass more critical dimensions of capitalist dynamics are more likely to capture the various forms of crisis that may occur.

James Crotty’s extensive writings (see references) on capitalism take precisely this expansive approach to crisis, and thus provide arguably the best basis for surveying the terrain of heterodox macroeconomic theory.4 Further, Crotty is without parallel in emphasizing that contemporary heterodox theory is both forward- and backward-looking: forward-looking in that it is based on a critique of orthodox theory, and backward-looking in being built largely on the living ideas of ancestral progenitors. And in addition, as discussed below, Crotty’s close reading of Marx led him to introduce the crucial distinction between the possibility and the occurrence of crisis into contemporary discourse. This distinction gave precedence to financial aspects of capitalism just as financial instability became a defining feature of the emerging neoliberal age.

Crotty’s critique of orthodoxy centers on four points:

- it presumes pre-coordination in market exchanges, thus denying the possibility that market outcomes can frustrate participants’ intentions;

- it ignores power;

- it ignores the role of firm strategy; and

- it pays no attention to the institutional features of real-world economies.

The first three of these critiques aim squarely at the orthodoxy’s approach to theory qua theory. In Crotty’s view, an opposition to orthodoxy must be based first and foremost on an analytically coherent counter-approach. To deny any model’s conclusions requires clarity about alternative assumptions that can generate other conclusions.

Following in the footsteps of both Marx (Crotty 1985) and Keynes (Crotty 1986), Crotty showed that embracing real time and ignorance means not only acknowledging the importance of fundamental uncertainty, but also discarding the possibility of pre-coordination.5 Even small failures in agents’ abilities to signal their intentions lead to aggregate demand/supply mismatches. That is, a real-time framework is invariably one in which unemployed labor and unsold goods are possible in equilibrium states. This in turn implies that aggregate demand has different determinants than aggregate supply, and may take on different magnitudes.

That is, Crotty’s orthodox framework is one in which Say’s Law–“supply creates its own demand”–does not hold. Crotty’s analysis was based in large part on—and helped to revive interest in—Marx’s ideas about the possibilities of crisis in his Theories of Surplus Value (especially Chapter 17). Marx, in these passages, not only anticipated Keynes’ reflections on the monetary implications of real time and uncertainty; they anticipated Minsky’s ideas about financial fragility.6 Crotty himself, as shown below, extensively studied and debated Minsky.

Drawing on his theoretical reflections on Marx, Keynes and Minsky, Crotty has emphasized that monetary and financial relations become uniquely important, and uniquely fragile when Say’s Law is violated. Important, because when everything does not happen at once, and when future outcomes are unknowable, those seeking goods must exchange either money or the promise of monetary payments to obtain them. To speed up the pace of production and exchange—and hence profit-making—capitalist firms will tend to use trade credit and other debt obligations (that is, obligations to provide monetary payment after goods or services are received) more. Fragile, because such latticeworks of credit become more likely to break down, the further they are extended in periods of tranquility or sustained growth. In effect, the very structure of economic transactions—the interpenetration of credit commitments and payments—creates the possibility of crises. Financial and credit relations are consequently a uniquely vulnerable element in capitalist reproduction. In short, any framework that embodies a critique of Say’s Law effectively recognizes the possibility for economic crisis. Given that all heterodox economists reject Say’s Law, a consideration of crises is central to heterodox analysis.

Another implication of a real-time framework is that the financial sector plays an “active” role in determining the level of employment and output. Insofar as the financial sector transfers funds from net savers to net borrowers, its assessments of real-sector risks and opportunities—not to mention the terms and conditions on which it makes loans—determine how much growth occurs, and how. So financial firms and wealth-owners, in contending with the unknowable, develop conventions in the face of uncertainty, and the confidence to believe their own conventions.

This leads immediately to the idea that financial instability is an inherent tendency in the capitalist economy: competitive pressures among firms and wealth-holders lead them to take on increasing degrees of leverage in search of higher rates of return; so when conditions change, they invariably are overcommitted. These pressures can lead to rapid asset-price shifts; and these shifts in turn undercut confidence further, leading to more instability, and so on.

The second element in Crotty’s critique involves orthodoxy’s inattention to power. Power in Crotty’s conception has both micro and macro dimensions. At the micro level, power is exerted in work-settings over those who must sell their labor to reproduce themselves, and whose labor is exploited by those who hire them. This exploitation is organized by the firms that manage the production processes creating the goods and services needed for human reproduction and consumption. At the macro level, power is asserted at the national or even super-national level. This last point—which places the insights of Boddy and Crotty into the international setting—leads to globalization of labor processes; and this brings the problematic of national power/hegemony into the discussion of economic fluctuations.

Crotty also insists on the importance of firms’ strategies, especially those of the large firms that shape market forces. The real-business cycle (and other mainstream) model(s) conceptualizes only the self-consistent behavior of one representative agent. But it is the possibly contradictory interactions of key sectors and key actors that demands our attention.7 In the financial sector, as noted, instability rests in lenders’ dual goals of minimizing their exposure to risks, on one hand, and their desire to maximize returns. Firms in the real sector also undertake self-undermining actions: for example, they expand production to widen their market reach in periods of economic expansion, while seeking to sustain profits by repressing wages. Again, outsourcing and global-factory solutions can mitigate the resulting tension between product-market demand and labor cost, but there is no avoiding a day of reckoning.8 As Crotty has put it, “in order to be able to explain adequately the dynamics of the capitalist economy, a macrotheory must root instability in both the real and financial sectors” (Crotty 1990:540)

Finally, Crotty insists on the importance of the institutional context within which cyclical and other economic forces play out. The lynchpin of Crotty’s work on Korea and its crisis, for example, is his appreciation of the unique set of institutions that had permitted Korea to grow rapidly for so long prior to the Asian financial crisis (Crotty and Dymski 1998).

From profit-squeeze in the USA to Korea in the grip of neoliberalism

In the realm of macroeconomic dynamics, a crisis occurs when the overall reproduction of social relations and asset values in the economic realm is jeopardized and/or breaks down. What are the links between the theoretical first principles discussed above and real-world crises? Crotty has applied his ideas about crisis principally to two episodes in recent history.9

Crotty’s celebrated essay with Raymond Boddy (1975) identified a “political business cycle” in the US economy of the 1960s and 1970s, triggered by recurrent profit squeeze. This model drew primarily on Kalecki and Marx to argue that US macro policy protected the interests of capitalists by slowing the economy—and thus deepening the reserve army of labor—when workers’ excessive wage demands threatened profit rates. This paper was prescient in pointing out tensions that had arisen amidst the “Golden Age”:

There are contradictions in the application of macroeconomic policy … First, as evidenced by the Indochina War, domestic cycle relaxation needs can conflict with the requirements of imperialist war. The latter obviously takes precedence, but only at the cost of severe future economic dislocations. Second, the internal need to discipline labor through the cycle conflicts with the long-term planning which is crucial if the U.S. is to regain undisputed international capitalist hegemony.

(Boddy and Crotty 1975:16)

Crotty’s work with Boddy emphasized the problem of power in capitalist relations. In the early 1980s, Crotty began to develop his ideas about the centrality of financial fragility and business strategy in capitalist crisis. This new approach to crisis came at a crucial time in the trajectory of heterodox macroeconomic theory. It was common, until the mid-1980s, to differentiate between shorter-term or cyclical models, such as the Boddy—Crotty framework, and longer-term of secular models, such as the Cambridge heterodox approach.10 Mimicking a distinction in neoclassical economics between demand-management and long-term growth models, the former class focused on fluctuations, the latter on longer-run equilibrium states. But by the 1980s, this conventional division collapsed, as the cyclical dynamics of the US economy were undergoing a fundamental shift, as the next two sections show. The US macroeconomy’s new empirical patterns challenged this distinction: the US macroeconomy’s formerly dependable cyclical patterns dissolved from 1980 onward; the long-run trajectory of the US economy slowed; and ferocious and unrestrained financial crises became a defining feature of the post-1980 world economy.

The age of globalization had arrived. And Crotty’s reconceptualization of crises as manifestations of theoretical possibilities of rupture—that unfold in institutionally-specific (and hence ever-changing) ways, and that heterodox theory can consider because of its pre-commitment to the importance of power, inequality, and instability—itself proved prescient.

Minsky on stabilizing instability in the US economy

Crotty’s multi-source, multi-influence approach to crisis, set out above (pp. 000–000), can be contrasted with that of Hyman Minsky—a celebrated heterodox macroeconomist who emphasized one progenitor (Keynes) and one root cause of crisis (financial instability). Crotty, while among Minsky’s deepest admirers, criticized his inattention to the determinants of investment, and by extension to capital—labor conflict. Crotty’s insights into capital—labor conflict can explain why Minsky’s policy prescription for capitalist instability falls short in the neoliberal era, and moreover help us to understand the ever-new faces and phases of crisis in the contemporary global economy.

Beginning in the 1970s, Hyman Minsky wrote a series of papers and books arguing that advanced capitalist economies are subject to cyclical variability because of their financial instability.11 The availability of financing boosts demand, but carries a cost: the economy becomes more financially fragile as financial commitments rise relative to income flows. Minsky argued that expectations, debt-financed expenditures and balance-sheet relationships—and hence financial fragility—evolve systematically during the business cycle, from “robust” to “fragile” to “Ponzi.” Eventually, a significant number of borrowers cannot meet repayment demands and cash-flow disruptions spread throughout the economy’s balance sheets. As financial instability worsens, asset values fall and a debt-deflation cycle may be unleashed.

Minsky argues that there was a fundamental transformation in the dynamics of capitalism because of Depression-era government policy reforms. In the pre-Depression era of what Minsky called “small-government capitalism,” financial instability operated via cataclysmic downward debt-deflation cycles, which wreaked havoc on wealth-owning and asset-owning units. As the 1929 stock market crash and 1933 banking holiday dramatically demonstrated, this was a very socially wasteful method of ridding the economy of unsustainable debt commitments. With the New Deal, in Minsky’s account, two crucial new roles for government were embraced: the Federal Reserve accepted its role as “lender of last resort” for the financial system; and the federal government committed to using public spending to stabilize aggregate demand.

These changes defined the initiation of “big-government capitalism.” Cyclical dynamics changed fundamentally, in Minsky’s characterization. Price deflation was checked by the interventions of the Federal Reserve and by counter-cyclical government expenditures. Consequently, the threat of debt-deflation was replaced by an inflationary bias. The huge increases in business failures, bank failures, and unemployment that had accompanied cyclical downturns were eliminated. Balance sheets are not thoroughly “cleaned” through widespread business failures in the downturn, as in the small-government period; so debt/income ratios build up over time. Investment too is stabilized at a low but positive level. Debt/income levels rise both cyclically and secularly. In effect, a tendency toward price inflation was the price of an interventionist state that “stabilized the unstable economy” (Minsky 1986). Minsky asserted that robust economic growth could resume once stable financial conditions were reestablished.12

Empirical evidence about Minsky’s big-government/small-government claim

Dymski and Pollin (1994) investigated Minsky’s claim that capitalism could be divided into “small” and “big” government eras, and that adequate policy tools for stabilizing the economy and assuring prosperity had been found. These authors collected annual US data for the period 1887–1988 for key variables in Minsky’s model. Observations in each data series were then grouped, using NBER business-cycle turning-point data. The observation for a given variable in a “peak” year preceding a downturn was denoted that for “year 0;” its value in the following year was termed “year 1,” and so on. Typical cyclical trajectories were then computed for these variables by averaging (without permitting any double-counting). The two periods of World War (1913–1918 and 1937–1951) were discarded.

Was Minsky right? Yes—to a point. Several variance-based tests determined that these cyclical patterns did indeed fall naturally into “small government” and “big government” groupings—but only until the arrival of the 1980s. The contrast between these two regimes is clearly seen in the contrasts in their average post-peak cyclical behavior.

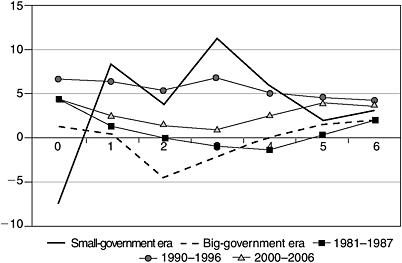

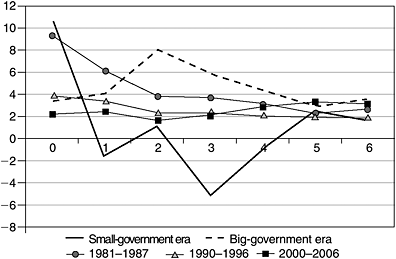

As Figure 5.1 shows, average GDP decline in the downturn is substantially larger in the small-government than in the big-government era. Big government puts a higher “floor” under real GDP growth. And while the unemployment rate (Figure 5.2) grew and remained high for a sustained period in the small-government era, in the big-government era its explosive growth was blocked, and it remained at a much lower level than in the previous era.

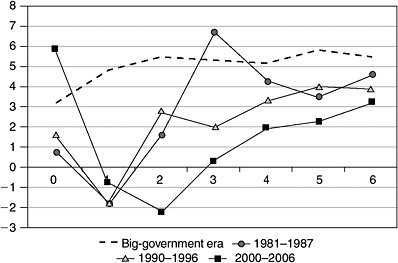

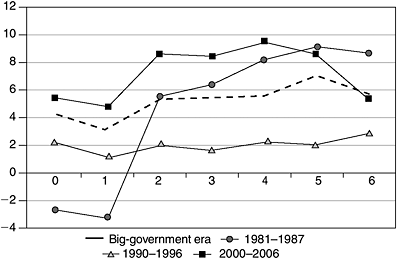

The contrast in the behavior of price movements is even sharper. Figure 5.3 shows the contrast between the two eras most dramatically. The cyclical data for the small-government era reveal the sustained deflationary momentum that follows the downturn. The big-government era is characterized instead by mounting inflationary pressure in the downturn, as the monetary authority intervenes and counter-cyclical spending is triggered. Here is evidence that government macro-managers are exploiting the inflation/stability tradeoff in favor of stability. The data for real interest rates in Figure 5.4, not surprisingly, show very similar patterns (since nominal interest rates usually move much less than prices over the cycle). In the small-government era, the real interest rate rises substantially and for a prolonged period after the peak—a pattern related to that era’s deflationary bias. By contrast, real interest rates fall after the peak in the big-government era due to Federal Reserve intervention.

Figure 5.3 Post-peak US price inflation (changes in GDP deflator): small and big government and neoliberal eras.

There are also strong contrasts between the post-peak behavior of stock market prices and of the bank failure rate.13 In the small-government era, stock-market prices decline and the bank failure rate climbs post-peak; in the big-government era, by contrast, stock-market prices actually rise in the post-peak period, while the rate of bank failures is low and shows no cyclical momentum.

Financial instability and crisis in the neoliberal era

If US cyclical patterns remained as they were prior to the 1980s, Minsky might have been right that “big government” could tame capitalist instability and assure managed prosperity. But they have not. To the contrary, post-1980 business cycles have followed a new behavioral pattern. Consequently, the idea of aggressive countercyclical government spending has evaporated: the US economy has left the “big government” era and entered the neoliberal age.

Neoliberal-era cyclical patterns

Cyclical dynamics have been transformed in the neoliberal era.14 As Figure 5.1 demonstrates, GDP growth rates in the neoliberal era show substantial variation. The 1981–1987 cycle is remarkably volatile; however, in the next two cycles, GDP growth rates have shown relatively little variability. In Figure 5.2, which depicts the cyclical dynamics of the unemployment rate, the neoliberal era marks a sharp break with the big-government pattern: in both the 1981–1987 and 1990–1996 periods, the unemployment rate climbs quickly to higher levels than in previous eras, and then drifts steadily downward.

Another sharp difference in the neoliberal era is seen in the price-movement data in Figure 5.3. The patterns for all three post-1970s business cycles are very similar, and utterly different than the big-government pattern. In the 1981–1987 and 1990–1996 data, inflationary pressure is highest at the initial business-cycle peak. This pressure then moderates steadily through the downturn and renewal of expansion. In the 2000–2006 data, there is literally no cyclical inflationary pressure. Similarly, as Figure 5.4 shows, the real interest rate—by contrast with the big-government era—are virtually constant through this period.

Cyclical movements in stock-market prices in the neoliberal era follow no single pattern; but the bank failure rate has varied in a revealing way. As the 1980s unfolded, the first significant wave of bank failures since the Great Depression era gradually gathered force. During the 1990s, this wave dampened; by the turn of the new century, the bank failure rate was again almost nil.

In short, the US economy has entered a new period of cyclical behavior from the 1980s onward. Real interest rates and price inflation no longer vary systematically over the cycle; these variables appear to be responding to forces other than the cyclical momentum of the US economy. Whatever measures are taken by government in the wake of recessions, they do not dampen the upward drift of the unemployment rate in the downturn.

In the USA, the neoliberal era has been defined by fundamental economic transformations: systematic financial deregulation; increasingly globalized financial and consumption markets; steadily declining real wages and unionization rates for workers in many industries; and outsourcing and the use of extended cross-border supply chains in production. The Reagan administration signalled a sea-change in social-welfare government spending, especially for the unemployed and the poor. Counter-cyclical and safety-net policies were rejected in favor of “supply-side” tax cuts. Percentage changes in post-peak per-capita federal outlays on individuals were substantially lower in the neoliberal era than in the big-government era.

Crotty’s sympathetic critique of Minsky

So what went wrong? Why all these changes, if the solution was already at hand? An explanation can be found in Crotty’s extended argument with Minsky over the nature of economic crisis.

These two thinkers had several face-to-face dialogs over the years. Crotty also reflected on Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis in several articles and chapters.15 On numerous occasions, Crotty praised Minsky’s analytical insight and his willness in policy debate to unabashedly advocate “big government” spending to combat stagnation (Crotty 1986: Introduction). But Crotty raised deep objections to Minsky’s conceptual apparatus. Crotty had a “thick” approach to crisis, encompassing numerous real- and financial-sector factors; Minsky had a “thin” approach, encompassing only financial factors.

Crotty observed that “Minsky can find no impediment to perpetual balanced growth in the real sector of the economy” (Crotty 1992:536). Minsky assumed that productive investment would follow passively from stable financial conditions; and while this may have reflected his sympathy for Schumpeter’s model of enterpreneurship (see footnote 12), in Minsky’s work, “the real sector of the economy has no active, essential role to play in the fundamental behavioral processes of his theory” (Crotty 1986:10). A further problem was Minsky’s inattention to labor-market or capital-labor relations. Crotty observed:

the constant-mark-up Kalecki model of profit determination used by Minsky … [is] quite unsatisfactory. This model assumes cyclical and secular constancy in the mark-up and the marginal efficiency of investment, the absence of any tendency for the rate of profit on capital to fall until after the expansion ends, and secular constancy in the rate of profit on capital.

(1986:6–7)

Not only were these assumptions contradicted by available empirical evidence; building them into the model blinded it to any potential instability in the capital—labor relationship due to wage-related conflicts or struggles over de-industrialization. But this was precisely a problematic aspect of cyclical dynamics in the big-government era. Figure 5.5 shows the problem clearly. Real wage/ salary payments rose systematically through the entire post-peak period, in the big-government era. This was the price for maintaining stability by reflating the economy just when it was perched to plunge into what would otherwise be a debt-deflation collapse. This figure also demonstrates that the cyclical behavior of real wage/salary payments was remarkably consistent and very different in the neoliberal era. Real wage/salary levels plunged after cyclical peaks in the neoliberal era.

How about the effect of the neoliberal era on profit rates? Figure 5.6 illustrates the post-peak behavior of profits by depicting year-over-year percentage changes in the manufacturing profit rate (calculated on an after-tax basis relative to owners’ equity). In the big-government era, profit rates rise mildly in the first year after the peak, and then fall; in general, their behavior is sluggish. In the neoliberal era, two distinct patterns are found. In the 1981–1987 period, the profit rate falls after the peak year, but then recovers. In the next two cyclical episodes, the profit rate falls after the peak, but then climbs spectacularly for an extended period.

Clearly, Minsky’s “hedgehog” model (in Pollin and Dymski’s 1993 characterization), which focused only on the need to check financial instability, provided a lens for seeing only a portion of the entire landscape of macroeconomic forces. The very factor that Boddy and Crotty emphasized—the constraints on the profit rate under the institutional conditions of the big-government era—was apparently among those that inclined owners of the US corporate sector to embrace the dismantling of the social-welfare state that had been built up since the 1930s (and dubbed big-government capitalism by Minsky).

Figure 5.5 Post-peak US real non-government wage and salary payments: big government and neoliberal eras (% change).

Figure 5.6 Post-peak changes in the manufacturing profit rate: big government and neoliberal eras (% change).

Global instability and stability in the neoliberal era

How did Minsky and Crotty adjust as the neoliberal era deepened? Minsky found that the major dangers in the neoliberal era would arise from the global spread of unchecked, highly-leveraged financial market relations. Even in his last essay, Minsky (1996) wrestled with the implications of what he called “money manager capitalism” and its implications for uncertainty and the problem of coordinating expectations in globalizing financial markets.

Crotty, by contrast, approached neoliberalism as a complex global phenomenon. His thick framework was far better suited to comprehend. His writing examined the global capital—labor struggle as well as the implications of the explosively growing financial markets. With the coming of the Asian financial crisis, Crotty made South Korea the focus of his study of neoliberalism. Korea was an apt choice. Not only had it so quickly changed places from “model of development” to a global site of rent-seeking elites, but Korea’s long-term success had proven fragile, masking a cauldron of state violence, class conflict and institutional power plays.

This contrast is not made to show that Minskyian financial crises are obsolete. To the contrary, financial instability is an ever-more-common feature of global dynamics, as the East Asian, Brazilian, Russian, Turkish and subprime-mortgage-based crises attest.16

Further, the search for stability—another of Minsky’s themes—has remained a key part of the global economy. Indeed, the most recent global crisis is rooted in that search.17 The roots of the subprime lending crisis are to be found in one of the global economy’s distinctive structural features since the mid-1980s—a growing US current-account deficit. This deficit has been balanced by steady financial inflows, many of which have bought mortgage-backed securities (MBSs). The volume of MBSs has grown dramatically, fed by the rapid growth of US mortgage loans—and in turn by some rapid advances in financial intermediaries’ capacity to bundle, securitize and sell mortgage debt into the market.

Figure 5.7 shows that except for two years of market disorganization in the early 1980s, real per-adult US mortgage debt has grown steadily. This growth is related, of course, to the US economy’s systematically low interest rates in the neoliberal era (Figure 5.4)–and the stagnant Japanese economy’s even lower interest rates (Slater, 2006). Further, mortgage debt has been relatively impervious to the business cycle. The willingness of many global funds to hold—and the low apparent risks associated with—MBSs led many lenders to devise fee-based strategies, paying little attention to recourse or default risk. Investors’ apparently insatiable demand for MBSs induced lenders to create instruments that teased new buyers into the market. Those previously excluded because of racial discrimination or because of inadequate savings or incomes could now have their housing purchases financed. The higher fees, rates and penalty clauses associated with these subprime mortgages meant both more income up-front for lenders and a steady set of steroid boosts to housing demand.

Ironically, the very fact that US-originated MBSs seemed to offer an island of tranquility in a world of chronic financial crises created incentives for perverse competitive forces. These ultimately have undermined entire portions of the US mortgage market—and threatened financial market stability the world over. The bank run of the 1930s has been transformed into the non-bank bank run—the liquidity black hole—of the new century (Persaud 2007).

Figure 5.7 Post-peak changes in mortgage debt: big government and neoliberal eras (% change in real per-adult debt).

Certainly, this situation is symptomatic of the transplanting of Minsky’s model of the US economy onto the global stage. The current crisis arose when US households’ burden of being simultaneously the world’s consumers of last resort and its borrowers of first resort, in a world of risk-evading financial intermediaries and shifting currency values, became too great to bear. Localized defaults spread, fed by intermediaries that have forgotten how to bear risk, and that now have the world’s economies into a global liquidity meltdown.

Minskyian policy measures have attempted to stabilize this latest instantiation of instability. Several times, the Federal Reserve’s “big bank” interventions have attempted to calm the markets and restore order (and liquidity).18 But these measures have not worked as intended. The Federal Reserve cannot get the cooperation it needs to ease cash-flows in ever more distant corners of the money markets. It is clear that as the neoliberal era goes on and unchained markets and bank strategies have gotten ever bolder, those who are assigned lender-of-last-resort duties are ever farther from knowing how to restore order. They simply do not control enough of the markets in which the players that have taken incalculable risks have made their plays.

So it is not enough to find out (and respond to), as Minsky liked to say, financial market-makers’ “model of the model.”19 The challenge is to find the crisis within the crisis. And here all the elements that Jim Crotty has identified for heterodox economics—instability, the active and sometimes destabilizing role of the financial sector, the use and abuse of power, firm strategies and the peculiar institutional framework of the neoliberal order—are there to be unwound.

Conclusion

Heterodox economists have long been united in agreeing that the neoclassical model constitutes a fundamentally flawed approach to understanding real-world economic dynamics. At the same time, they have otherwise constituted a group whose diversity of approach sometimes seems Babel-like: it is not just that followers of Keynes diverge from followers of Marx, but that followers of Keynes and of Marx disagree among themselves about how to construct more representative models of capitalist relations. This creative, if cacophonous, outpouring of insight leads to two central problems: what does define heterodox theory in economics? And how can one choose which approaches in heterodox theory show more promise?

This chapter has argued that the term “heterodox” should apply to all theoretical approaches that build in the assumption that capitalist economic relations are prone to immanent breakdown for endogenous reasons. Heterodox theory is coterminous with approaches that view crises of reproduction as a defining characteristic of capitalist economies. How then to choose which are the more promising approaches to heterodox theory? We have argued here that heterodox economic theory should be thick—sensitive to the possibility that reproduction crises can arise in several different ways—and not thin (focused on one source of breakdown).

The ideas of James Crotty provide an exemplar of the approach to heterodox theory set out here.

Crotty places the problem of crisis—sustained breakdowns in economic reproduction—not evolution, at the center of the heterodox agenda. He is careful to acknowledge and build on ideas handed down from intellectual progenitors. Further, in Crotty’s vision, no contributor can or should settle on one source of crisis, or on one solution to crisis. Crises can arise due to asymmetric economic power, the vicissitudes of uncertainty, or inconsistent firm strategies—or due to contradictory interactions among these elements. There is no magic bullet. The analyst should not simplify too quickly, but should continually examine her logic from the multiple points of view that co-exist, however uneasily, within the firelit sanctuary of heterodox theory.

To illustrate these two approaches within heterodox theory, Crotty’s approach has been contrasted here with Minsky’s “hedgehog”-like financial-fragility framework. This chapter has shown that Minsky’s model does not hold up as a characterization of economic dynamics in the neoliberal era. This doesn’t mean Minsky is wrong; to the contrary, his ideas—as the subprime crisis shows—are more relevant than ever. But his approach should be extended so that it fully integrates real-sector influences on financial crises, and so it accounts for the new macro realities, including shifting financial markets and processes, that have unfolded in the neoliberal era.

What will bring economics out of this neoliberal midnight? None can say. But might not this renewal start with a flickering insight, born in the uneasy reflections of a heterodox imagination? It would not mark the first time that devalued but carefully kept traditions have rekindled our understanding of what has happened, and what must be done next in the world in which we live:

As I see it, Marx, Keynes, and Minsky might all be embarrassed to be found in bed together, but they are not such strange bedfellows after all. Each has his role to play in constructing a theory of political economy adequate to our needs.

(Crotty 1986:29)

Notes

1 There is not space here to work through the specific implications of the removal of time, ignorance and power from market-exchange frameworks. For detailed examinations of these relationships, see Crotty (1985), among others.

2 This is not to belittle the usefulness of equilibrium reproduction frameworks as indicative tools and as points of reference within heterodox theory. Understanding how something works is fundamental in understanding how it can break down: the analysis of balanced growth is a useful means to the end of examining impediments to growth. This way of understanding equilibrium growth frameworks, of course, implies that crises are not simply short-run phenomena experienced on the way to long-term steady states; to the contrary, these steady states are reference points for understanding crisis.

3 And it is often misunderstood in the latter way. For example, a New York Times reporter (Hayes 2007) wrote that “heterodox” “categorizes people by what they don’t believe … in the case of heterodox economists, what they don’t believe is the neoclassical model that anchors the economics profession.”

4 We have not emphasized the micro/macro distinction, as it is not important for the larger argument being made in this chapter. Crotty’s writings have examined both macroeconomics and paid little attention to explicitly microeconomic frameworks.

5 Also see Dymski (1990).

6 See Crotty (1985, 1986).

7 The inescapability of contradictory relationships among economic agents and structures is one reason why, in Crotty’s conception, macroeconomic dynamics lead to recurrent crises, and also why crises involve interactions at a macro-scale; see Crotty (1993b).

8 There is recent evidence that China is beginning to confront labor shortages; see Barboza (2006).

9 Crotty’s writings about real-world capitalist crises represent contributions to the broader landscape of heterodox crisis theories. Kotz (2006) sets out a useful typology of heterodox crisis theories.

10 This latter bias is especially evident in Marglin (1984).

11 See especially Minsky (1975). Pollin and Dymski (1993) succinctly summarize his framework.

12 Minsky believed that sustained financial stability would permit Schumpeterian entrepreneurs to obtain financing and create new sources of employment and investment (Minsky 1986; Ferri and Minsky 1992).

13 These data are not shown here, but are available from the author.

14 This argument is developed in Dymski (2002), which extends the Dymski—Pollin method for the first two post-1970s cycles and presents some pertinent comparative data for the three eras.

15 See especially Crotty (1986, 1990, 1993a).

16 See Kregel (1998) and Crotty and Dymski (1998), among others.

17 Two useful discussions of this unfolding crisis are Slater et al. (2007) and Ip and Hilsenrath (2007).

18 As Kregel notes, this “big bank” role far outweighs the “big government” role in global financial crises.

19 The phrase was Peter Albin’s; it is quoted in Minsky (1996).

References

Barboza, D. (2006) “Labor Shortage in China may lead to Trade Shift,” New York Times, April 3.

Boddy, R. and Crotty, J. (1975) “Class Conflict and Macro-Policy: The Political Business Cycle,” Review of Radical Political Economics, 7: 1–19.

Crotty, J. R. (1985) “The Centrality of Money, Credit, and Financial Intermediation in Marx’s Crisis Theory: An Interpretation of Marx’s Methodology,” in S. Resnick and R. Wolff (eds.) Marxian Political Economy: Essays In Honor of Harry Magdoff and Paul Sweezy, 45–82, New York: Autonomedia.

——(1986) “Marx, Keynes, and Minsky on the Instability of the Capitalist Growth Process and the Nature of Government Economic Policy,” in David F. Bramhall and Suzanne W. Helburn (eds.) Marx, Schumpeter, and Keynes: A Centenary Celebration of Dissent, 297–326, Armonk: M. E. Sharpe.

——(1990) “Owner-Manager Conflict and Financial Theories of Investment Instability: A Critical Assessment of Keynes, Tobin, and Minsky,” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 12(4): 519–42.

——(1992) “Neoclassical and Keynesian Approaches to the Theory of Investment,” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 14(4): 483–96.

——(1993a) “Rethinking Marxian Investment Theory: Keynes—Minsky Instability, Competitive Regime Shifts and Coerced Investment,” Review of Radical Political Economics, 25(1): 1–26.

——(1993b) “Structural Contradictions of the Global Neoliberal Regime,” Review of Radical Political Economics, 32(2): 361–8.

Crotty J. R. and Dymski, G. A. (1998) “Can the Global Neoliberal Regime Survive Victory in Asia? The Political Economy of the Asian Crisis,” International Papers in Political Economy, 5(2): 1–47.

Debreu, G. (1959) Theory of Value. New York: Wiley.

Dymski, G. A. (1990) “Money and Credit in Radical Political Economy: A Survey of Contemporary Perspectives,” Review of Radical Political Economics, 22(2/3): 38-65.

——(2002) “Post-Hegemonic U.S. Economic Hegemony: Minskian and Kaleckian Dynamics in the Neoliberal Era,” Keizai Riron Gakkai Nempo (Journal of the Japanese Society for Political Economy), 39(April): 247–64.

Dymski, G. A. and Pollin, R. (1994) “The Costs and Benefits of Financial Instability: Big-Government Capitalism and the Minsky Paradox,” in G. Dymski and R. Pollin (eds.) New Perspectives in Monetary Macroeconomics: Essays in the Tradition of Hyman P. Minsky, 369–401, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Ferri, P. and Minsky, H. P. (1992) “Market Processes and Thwarting Systems,” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 3(1): 79–91.

Hayes, C. (2007) “Hip Heterodoxy,” New York Times, June 11.

Ingrao, Bruna and Giorgio, I. (1990) The Invisible Hand: Economic Equilibrium in the Hostory of Science. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ip, G. and Hilsenrath, J. E. (2007) “How Credit Got So Easy And Why It’s Tightening,” Wall Street Journal, August 7, A1.

Kotz, D. M. (2006) “Crisis Tendencies in Two Regimes: A Comparison of Regulated and Neoliberal Capitalism in the U.S.,” mimeo, Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, December.

Kregel, J. (1998) “Yes, ‘It’ Did Happen Again—A Minsky Crisis Happened in Asia,” Working Paper No. 234, Jerome Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, April.

Marglin, S. A. (1984) Growth, Distribution, and Prices. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Minsky, H. P. (1975) John Maynard Keynes. New York: Columbia University Press.

——(1986) “Money and Crisis in Schumpeter and Keynes,” in David F. Bramhall and Suzanne W. Helburn (eds.) Marx, Schumpeter, and Keynes: A Centenary Celebration of Dissent. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe.

——(1996) “Uncertainty and the Institutional Structure of Capitalist Economies,” Working Paper No. 155, Jerome Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, April.

Persaud, A. (2002) “Liquidity Black Holes,” WIDER Discussion Paper No. 2002/31, United Nations University, March.

——(2007) “The Politics and Micro-economics of Global Imbalances,” in A. F. P. Bakker and I. R. Y. van Herpt (eds.) Central Bank Reserve Management: New Trends from Liquidity to Return, 37–45, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Pollin, R. and Dymski, G. A. (1993) “Hyman Minsky as Hedgehog: The Power of the Wall Street Paradigm,” in Steven Fazzari (ed.) Financial Conditions and Macroeconomic Performance, 27–62, Armonk: M. E. Sharpe.

Slater, J. (2006) “Dollar’s Tumble May Hurt Players In Carry Trade,” Wall Street Journal, December 13, C1.

Slater, J., Lyons, J., Barta, P. and Davis, A. (2007) “Markets Fear U.S. Woes Will Hit Global Growth,” Wall Street Journal, August 17, A1.