9 Did financialization increase macroeconomic fragility?

An analysis of the US nonfinancial corporate sector

Özgür Orhangazi

Introduction

The post-1980 era has been characterized by weak global aggregate demand growth and intensified competition in key product markets, which led to low profits and chronic excess capacity. At the same time, financial markets greatly expanded and put increased pressure on nonfinancial corporations (NFCs) to generate higher earnings and distribute them to the financial markets.1 Unable to increase their profits due to adverse conditions in the product markets, NFCs were forced to pay an increasing share of their internal funds to financial markets. They responded to this paradox with a change in their corporate strategies and long-term growth orientation left its place to short-term survivalist strategies that prioritized increasing returns to shareholders. The establishment of a market for corporate control with its hostile takeover waves, the rise of the “shareholder value movement,” and changes in managerial incentive structures shortened the NFC planning horizons and led the NFC management to change their priorities and increase dividend payments and/or buyback firm’s own stocks in an attempt to meet financial market demands. This was accompanied by an increase in NFCs’ investments in financial assets and subsidiaries. In a process now commonly referred to as financialization, the relationship between financial markets and the NFCs was fundamentally transformed.2

In this chapter, I argue that financialization increases the potential instability and the degree of financial fragility in the nonfinancial corporate sector. First, the dominance of financial markets’ short-termist perspective adds to the inherent instability of the investment demand. Second, NFCs’ high indebtedness leads to a higher degree of financial fragility. This is further complicated with the earnings pressure of the stock market and with increased involvement of NFCs in financial investments. Third, the “neoliberal paradox” together with the proliferation of new financial instruments heightens the uncertainty in the economy by creating increasingly less transparent financial dealings. Before moving onto the discussion, I should make it clear that my purpose in this chapter is not to develop a formal model of financial fragility and instability in a financialized economy, but rather to outline the potential sources of fragility and instability for the NFCs. Also, while many have pointed out that the financial sector participants now engage in increasingly risky ventures and hence heighten the potential fragility of the system, this chapter will only focus on the NFCs and present a partial analysis in that sense.3

Instability of “coupon pool” capitalism

A main feature of twentieth-century US capitalism has been the separation of ownership and management. This ensured that the day-to-day requirements of business were carried out by a professional managerial class, who over time gained autonomy from the financial capitalists that owned the firms. During the “Golden Age,” NFC management followed a strategy of retaining their earnings and reinvesting them in projects with long-term growth prospects and long-run profitability. However, starting in 1980s the relationship between the NFCs and the financial markets in the US economy was fundamentally transformed. The corporate strategy has been reconfigured around distributing a higher share of earnings to shareholders; a shift from “retain and reinvest” to “downsize and distribute” (Lazonick and O’Sullivan 2000). With the rise of institutional investors such as mutual funds, pension funds and insurance companies, the takeovers advocated by agency theorists became possible and the shareholders gained collective power to directly influence both the management of NFCs and the returns and prices of corporate shares they held. Financial firms shifted their focus from supporting long-term investment activities of NFCs through long-term financing to trading securities and generating fees and capital gains (Lazonick and O’Sullivan 2000).

This transformation created a “coupon pool capitalism” where corporations first return their earnings to financial markets and then compete to re-acquire these funds. In this configuration the coupons are

all the different kinds of financial paper (bonds and shares) traded in the capital markets and coupon pool capitalism exists where the financial markets are no longer simple intermediaries between household savers and investing firms but act dynamically to shape the behaviour of both firms and households.

(Froud et al. 2002:120)

“Coupon pool” capitalism increases the potential instability of the system in two ways. First, it exacerbates the fundamental contradiction between the necessity of long lasting investment in production and the demand of absolute free movement of finance capital (Dumenil and Levy 2005:40). Impatient financial markets of the financialization era demand that NFCs discharge an ever-growing part of their earnings to the financial markets and keep the stock prices rising. This is a reflection of the shift in the beliefs and understanding of finance capital

from an implicit acceptance of the Chandlerian view of the large NFC as an integrated, coherent combination of relatively illiquid real assets assembled to pursue long-term growth and innovation, to a “financial” conception in which the NFC is seen as a “portfolio” of liquid sub-units that home-office management must continually restructure to maximize the stock price at every point in time.

(Crotty 2005:88)

When firms discharge their earnings to the financial markets and then compete to re-acquire them, the planning horizon for investment funding is shortened and the degree of uncertainty is heightened. Unlike the earlier period of “retain and reinvest,” managers now cannot be sure of the amount and cost of the funds they will be able to re-acquire. This could especially hamper investments that have longer periods of gestation by creating uncertainty about the ability of the firm to finance the projects in the coming years. The pressure to provide high short-term returns to shareholders can shorten planning horizons for NFCs too, as the attempt to meet the short-term expectations of the financial markets, rather than investment in long-term growth of the firm, becomes the primary objective.4 This creates a situation in which the vulnerability of NFCs to adverse economic developments is increased as impatient financial markets can withdraw credit at the first sign of weakness. A slowdown in economic growth could quickly be translated into a withdrawal of funds and further deepen the recession. As I discuss below, the situation is complicated by the increased degree of financial fragility the NFCs face today.

The second impact of the “coupon pool” is similar, but in the opposite direction: financial markets can cause rapid overheating of an expansion. Both Keynesian and Marxian approaches to instability stress that finance capital is an important and dominating accelerator of the growth process and a destabilizer at the same time (Crotty 1986). The credit system allows the accumulation process to take place at a faster pace and an expanded scale that otherwise would not be attainable. When the conditions are favorable and investment expands rapidly, the resulting increase in confidence levels leads firms to make use of greater amounts of credit while the creditors make more loans, some of which are increasingly riskier. The pace and the scale of the expansion then depend on the amount of the finance capital thrown into the expansion. However, these expansions prepare their own ends as they endogenously produce either financial or real problems within the economy (Crotty 1986). Financialization makes the allocation of funds across industries and firms largely subject to the volatile expectations of large financial institutions, including institutional investors. These institutions are mostly focused on acquiring high returns on their investment in the short-run. The high-tech boom of the second half of the 1990s provides a good example. In the height of the boom “pension funds and capital market institutions were prepared to throw capital at new economy companies that had no earnings and uncertain prospects of profiting from digital economies” (Feng et al. 2001). The result was a rapid expansion in the industry with significant levels of over-investment until the boom came to an end in early 2000s.5 The new configuration, hence, is likely to exacerbate the role of finance capital in generating speculative expansions or overheating expansions in growing industries.

Debt and fragility

Financial fragility refers to the vulnerability of economic units to adverse economic developments that put their ability to meet payment obligations at risk.6 In general, an economy is thought to be more financially fragile as financial payment commitments as a ratio of earnings increase and a smaller disturbance in earnings can potentially disrupt the ability of economic units to fulfill their payment commitments. Adverse economic developments in the product markets, such as a decline in profitability, or disturbances in the financial markets, such as rising interest rates or a spectacular failure that leads to the erosion of confidence can then create a larger impact on the system. A fragile “financial system can turn what might have been a mild downturn into a financial panic and depression” (Crotty 1986:306) and have a significant impact on the participants of the financial system as well as the whole economy.

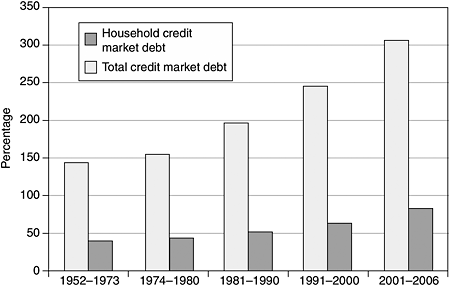

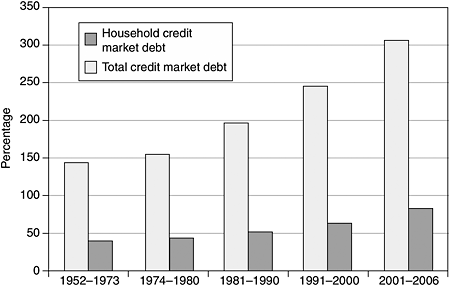

Compared with the Golden Age, it is clear that financialization brought a spectacular increase in the debt levels in the recent decades. Total credit market debt as a percentage of GDP, which stood below 150 percent in the period of 1952–1973, showed a secular increase and exceeded 300 percent in the 2001–2006 period. Household borrowing in the same period more than doubled and averaged above 80 percent after 2001 (see Figure 9.1). Average NFC credit market debt as a percentage of NFC net worth was around 30 percent during the Golden Age, but exceeded 50 percent in the 1990s, before declining to an average of 46 percent in the 2000s (see Figure 9.2).

Figure 9.1 Total and household credit market debt as a percentage of GDP (source: Flow of Funds Accounts, Tables L.1 and F.6).

Figure 9.2 NFC credit market debt as a percentage of NFC net worth (market value) (source: Flow of Funds Accounts, Table B.102).

Starting in the late 1960s into the early 1980s, NFCs in the US faced increasing international competition while at the same time facing declining profitability. As a response to increased competition, NFCs undertook coercive (or defensive) investment and shrinking internal funds led firms to finance this investment through increased borrowing. The transformations in financial markets created three additional factors that raised NFC indebtedness. First, faced with a hostile takeover movement in the 1980s during which nearly half of the major corporations in the US received a takeover offer (Mitchell and Mulherin 1996), managers of targeted firms defended their turfs by loading the firm with debt to deter potential raiders (Crotty 2005:90). At the time, increased indebtedness of firms was also perceived as a good solution to the potential agency problems. Second, especially in the 1990s, managers started using debt-financed stock buybacks and special cash dividends to deter a potential takeover attempt, maximize the value of their stock options, meet shareholder value targets and keep the earnings per share and dividend growth increasing. For example, during the 1990s boom, when the profits peaked in 1997

companies have compensated for a declining return on total capital employed by leveraging their balance sheets in order to maintain the return on equity. They repurchased shares so that earnings per share and dividend growth increased at the cost of balance sheet deterioration. The resulting shrinkage in stock market equity helped support stock prices, and returns on directors’ stock option plans.

(Plender 2001)

Furthermore, as I discuss below, the increased stock buybacks and dividend payments leave NFCs with limited internal funds and hence create an additional force to borrow in order to finance their normal operations. Finally, while NFCs engaged in coercive investment in an attempt to keep their turf in the face of increasing international competition they also found another venue in financial investments and started using part of their borrowing in financing their holding of financial assets.

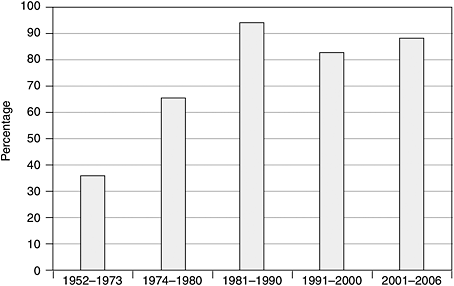

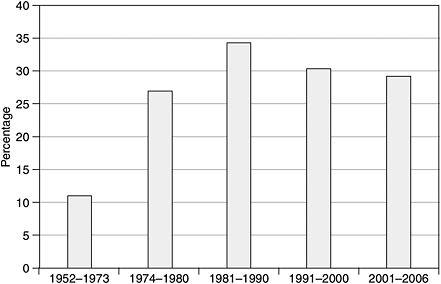

When NFCs are heavily indebted, even minor increases in the interest rates or minor declines in the profit flows can lead to financial problems for them. This is because high indebtedness implies that an increasing portion of future earnings is now committed to interest payments and debt repayments. The ratio of NFC financial liabilities to internal funds cycled between four and six in the period of 1952–1973, then increased rapidly (see Figure 9.3). Despite a decline in recent years due to a strong recovery in profits, the average ratio still stood above eight in the 2000s. When debt is used to finance profitable investments, as these investments pay off in time the firms can meet their payment obligations. However, an adverse economic development that hurts the earnings of the firm, a decline in the confidence level, or a rise in the interest rates could result in firms with high levels of debt facing problems in meeting their contractual payment obligations. The degree of fragility then depends on the share of firms that constitute, in Minsky’s terms, hedge, speculative or Ponzi financing units.7 At the aggregate level NFCs gross interest payments as a percentage of their internal funds have more than doubled in the era of financialization. In the Golden Age era, less than 20 percent of NFC total internal funds was used to meet gross interest payments. This ratio exceeded 50 percent between 1981 and 1990 and then fell down thanks to lower interest rates in the 1990s and a strong recovery of the profits in the 2000s (Figure 9.4). However, a downturn in profitability or an increase in interest rates could easily reverse this trend. These contractual payment obligations make NFCs less flexible in their use of internal funds. NFCs either have to find ways to keep increasing their profitability or risk not being able to meet their payment obligations in the face of an economic downturn.

Figure 9.3 NFC financial liabilities as a percentage of internal funds (source: Flow of Funds Accounts, Tables B.102 and F.102).

Note

Internal funds equal to total internal funds with inventory valuation adjustment plus net dividends.

Figure 9.4 NFC gross interest payments as a percentage of internal funds (source: Flow of Funds Accounts, Tables F.102 and National Income and Product Accounts Table 7.11).

Note

Internal funds equal to total internal funds with inventory valuation adjustment plus net dividends.

Non-contractual financial payments

Rising debt and interest payment ratios constitute only one side of the financialization story. On the other side, a significant chunk of firm earnings is taken by non-contractual financial payments: dividend payments and stock buybacks. Even though, in theory, equity financing does not create any contractual payment obligations, firms now have to meet the financial markets’ demands for these payments and provide satisfactory returns. Otherwise, management risks losing its position/autonomy and the firm may face a takeover threat, a withdrawal of financing or difficulty in raising funds for new projects.

Total financial payments including gross interest payments, dividend payments, and stock buybacks now consume, on average, more than 80 percent of the NFC internal funds (Figure 9.5). It is important to note that despite a decline in interest payments, total financial payments ratio has stayed high in the 2000s. In effect, this forces firms to finance their operations externally, and use debt, not equity, since firms are buying back their stocks, and hence contribute to increased indebtedness. In the event of an earnings crisis, firms would not be able to meet, at the very least, some of these payments. Non-contractual financial payments may be the first to be cut, however this may have larger implications through their effect on the price of shares and shareholder earnings and further complicate the situation for the firm. Hence, financialization, through NFC financial payments, ties the credit market and stock market in a new way. This is likely to increase the fragility of the NFCs in particular and the financial system in general. In this new configuration, the interactions between downturns in asset markets, credit market contraction, investment and financial payments become all the more important. At a time of earnings crisis, the NFCs now face the danger of not being able to meet either contractual (interest) or non-contractual (dividends and stock buybacks) financial payments, each of which implies further instability.

Figure 9.5 NFC total financial payments as a percentage of internal funds (source: Flow of Funds Accounts, Tables F.102 and National Income and Product Accounts Table 7.10–11).

Note

Internal funds equal to total internal funds with inventory valuation adjustment plus net dividends.

Financial incomes and fragility

Another complication introduced by financialization is that a sizeable portion of the NFC earnings now comes from financial sources. Interest and dividend incomes make up on average more than 25 percent of the NFC internal funds during the 1981–2006 period (Figure 9.6).8 This change in the NFC earnings structure has three interesting implications for financial fragility. First, increasing financial investments can support the real incomes when they are in the form of credit extended to the firm’s customers. In this case, firms can use the financial resources available to them to fend off earning problems from their real operations and hence prevent or postpone a profitability crisis that could otherwise set off financial fragility events.

Figure 9.6 NFC financial income as a percentage of internal funds (source: Flow of Funds Accounts, Tables F.102 and National Income and Product Accounts Table 7.10–7.11).

Note

Internal funds equal to total internal funds with inventory valuation adjustment plus net dividends.

Second, although financial incomes can potentially support earnings, they are inherently more volatile than regular expected gross earnings. For example, even small changes in the interest rates could potentially have large impacts on the financial earnings of the NFCs. Therefore, an extra risk is introduced to the expected earning streams of the NFCs and the prospects of future earnings now depend not only on the product markets but also financial markets. For example, the Wall Street Journal reports that, in a version of “carry trade” NFCs add to their profits through borrowing at short-term rates and lending directly or through the purchase of securities at higher long-term rates (Eisinger 2004). As long as the difference between these two rates is high, this is a very profitable trade for NFCs. However, if the short-term rates increase faster than long-term rates a good portion of these earnings would quickly disappear.

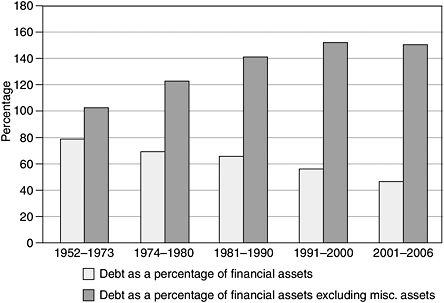

Third, the larger share of financial assets on NFC balance sheets makes them more solvent at least at the micro level. NFC debt as a percentage of total financial assets is now at its lowest level (Figure 9.7). As opposed to irreversible real investment, in liquid markets firms can easily convert back to cash to meet their payment obligations. Of course, when all firms attempt to do this in the face of a downturn then a deflation in the financial asset markets would be inevitable.

Figure 9.7 NFC debt as a percentage of NFC financial assets (source: Flow of Funds Accounts, Tables B.102).

Moreover, using debt to finance financial investments also creates the risk of maturity mismatch—a situation where assets are long term and liabilities are short term. This creates two potential points of fragility: rollover risk (that maturing debts will not be refinanced and the debtor will have to pay the obligation) and interest rate risk (that the structure of interest rates change against the NFCs’ financial investments).

The changes in the rate of returns on assets and liabilities, the different maturity structures and different liquidities in financial markets could introduce further risks for the NFCs—risks mostly associated with banks and other financial institutions. However, it is not possible to analyze these risks properly as we do not have detailed data on financial asset holdings of the NFCs where almost half of the NFC assets are classified as miscellaneous (Figure 9.7). One might argue, on the contrary, that the NFCs can use their financial investments in hedging. It is certainly true that leverage makes it cheaper for NFCs to hedge, however it also makes it cheaper to speculate. Although at the macro level we do not have enough data to analyze the degree of hedging and speculation by NFCs, anecdotal evidence suggests that they are certainly involved in the business of financial speculation. For example, in 2006 Sears earned more than half of its third-quarter net income from investments in financial derivatives: “These derivatives known as ‘total-return swaps’ are agreements that take on the big risks of highly leveraged investments in equities or other assets without actually buying them or assuming debt to purchase them” (Covert and McWilliams 2006).

In short, the involvement of NFCs in financial investments might help them in hedging and increasing their solvency but at the same time introduces new risks to their balance sheets and earning streams. This also brings up another feature of financialization, the inherent non-transparency of these financial involvements.

Non-fundamental uncertainty

Keynes famously declared that the future is fundamentally unknowable. In the age of financialization, however, not only the future but also the past and the present are becoming increasingly unknowable. At the general level, financial dealings have become more and more complicated. For example, Partnoy (2003) shows that financial engineering reached to a point where they are now inherently non-transparent. Not only the general public but even the top executives of the financial institutions do not have a clear understanding of these complex financial dealings. Although evidence suggests that NFCs are involved in many complicated financial ventures, the extent of these investments is unknown. The hazards of this new type of uncertainty is likely to manifest itself during times of financial distress when markets in complex financial assets become illiquid and firms cannot even value the assets on their balance sheets. As a Wall Street Journal article written in the aftermath of the mortgage crisis of 2007 puts it “large parts of American financial markets have become a hall of mirrors” (Pulliam et al. 2007).

Added to this is the conscious deception introduced by fraudulent earnings reports, which unraveled at the end of the 1990s’ boom with famous examples of Enron and WorldCom. In the case of Enron, the extent of debt was hidden by creating off balance sheet instruments, while WorldCom executives manipulated earnings information. Forced by financial markets to provide high returns to shareholders, many NFCs constrained by product markets, chose to use financial engineering where major restructurings and changes of ownership were used to present favorable earning statements (Froud et al. 2000:109). Obfuscation of earning information delivered by companies became a standard practice (Parenteau 2005:128–31). As Crotty (2005:100) points out “destructive competition in product markets in the past quarter of a century has severely constrained the ability of NFCs to earn high profits and cash flow, yet financial markets demand ever-rising earnings to support ever-rising stock prices” and “given conditions in product markets, nothing but massive fraud and deception could possibly have kept stock prices from falling after 1997” (p. 101). Therefore, the very forces of financialization with its incentive and reward structure, opportunities it presents, and complicated financial instruments make NFCs’ financial dealings unknowable, which unavoidably introduces further risks into the system. This also shows that the financial markets do not necessarily act as an external disciplinary force since most of these dealings are to satisfy the financial markets’ inflated stock price demands.

Concluding remarks

Financialization has increased the potential fragility of the NFCs in various ways. High indebtedness and the changes in the institutional framework cause NFCs to devote an increasing share of earnings to financial payments. This could have significant implications if firms were to face an earnings crisis. Furthermore, a larger share of these earnings now comes from financial sources, which are inherently more volatile and make the firm earnings dependent not only on product markets but also financial markets. Financial investments of the NFCs might decrease fragility by enabling hedging and by supporting their real income. However, financial investments also bring in new risks, such as a potential asset—liability mismatch and increased risks due to easy speculation. Furthermore, the transformation of the institutional framework makes NFCs more susceptible to wild inflows and outflows of financial capital. On the one hand, impatient financial markets can now withdraw credit at the sign of first weakness, and on the other hand they can finance an overexpansion, as seen in the NASDAQ boom of the 1990s. Added to all these is the non-transparency of most financial dealings that potentially increases the uncertainty for investors and managers alike.

Two caveats are in order. First, one needs to be careful with the argument that financialization increases potential instability and fragility, as it runs the danger of concluding a certain crisis ahead. While an increase in financial fragility certainly makes a widespread crisis more likely, adjustments and structural changes by the NFCs as well as policy interventions to avert a crisis can also be expected. In the face of increased fragility and crisis-proneness of the system, significant changes can occur in the coming years. However, we can only wait and see if these adjustments will be abrupt and devastating or slow and extended. Second, the data analyzed in this chapter are at the aggregate level. Although aggregate analysis is quite valuable in depicting macroeconomic tendencies, it implicitly assumes either that the whole sector is one giant firm or it is composed of representative firms all responding in the same way to any change. Further studies at firm and/or industry levels would contribute to a more detailed and precise understanding of how financialization affects the fragility of NFCs.

Notes

1 This created what Crotty (2005) called a “neoliberal paradox.”

2 See Crotty (2005) for a detailed exposition of the “neoliberal paradox” and financialization.

3 For example, Crotty (2007) points out that US banks increased their exposure to risk, while Dodd (2005) discusses the role of derivatives markets as the sources of vulnerability in financial markets.

4 See Orhangazi (2008a) for an analysis of the effects of financialization on NFC investment demand.

5 See Parenteau (2005) for a discussion of the investor dynamics behind the boom.

6 See Minsky (1986, especially chapters 8 and 9) for a succinct description of financial fragility. Marx referred to the similar situation as “oversensitivity.” See Crotty (1986) for a discussion of parallels and differences of Minsky’s approach to Marxian crisis theories and the importance of integrating the strengths of both theories.

7 A hedge unit is able to meet its payments with cash receipts; a speculative unit has difficulty in meeting some payments; and a Ponzi unit must borrow to meet its current interest payments.

8 This ratio increases if one includes capital gains in the financial incomes as well (Krippner 2005). See Orhangazi (2008b) for causes and consequences of the increased involvement of NFCs in financial investments.

References

Covert, J. and McWilliams, G. (2006) “At Sears, Investing—Not Retail—Drive Profit,” Wall Street Journal, November 17, C1.

Crotty, J. (1986) “Marx, Keynes and Minsky on the Instability of the Capitalist Growth Process and the Nature of Government Economic Policy,” in S. Helburn and D. Bramhal (eds.) Marx, Schumpeter, Keynes: A Centenary Celebration of Dissent, 297–326, Brooklyn: Sharpe.

——(2005) “The Neoliberal Paradox: The Impact of Destructive Product Market Competition and ‘Modern’ Financial Markets on Non-financial Corporation Performance in the Neoliberal Era,” in G. Epstein (ed.) Financialization and the World Economy, 77–110, Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

——(2007) “If Financial Market Competition is so Intense, Why are Financial Firm Profits so High? Reflections on the Current ‘Golden Age’ of Finance,” Political Economy Research Institute Working Paper No. 134, University of Massachusetts.

Dodd, R. (2005) “Derivatives Markets: Sources of Vulnerability in US Financial Markets,” in G. Epstein (ed.) Financialization and the World Economy, 149–180, Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Dumenil, G. and Levy, D. (2005) “Costs and Benefits of Neoliberalism: A Class Analysis,” in G. Epstein (ed.) Financialization and the World Economy, 17–45, Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Eisinger, J. (2004) “Interest Rates, Corporate Profits,” Wall Street Journal, February 9, C1.

Feng, H., Froud, J., Johal, S., Haslam, C. and Williams, K. (2001) “A New Business Model? The Capital Market and the New Economy,” Economy and Society, 30(4): 467–503.

Froud, J., Johal, S. and William, K. (2002) “Financialization and the Coupon Pool,” Capital and Class, 78: 119–51.

Krippner, G. (2005) “The Financialization of the American Economy,” Socio-Economic Review, 3(2): 173–208.

Lazonick, W. and O’Sullivan, M. (2000) “Maximizing Shareholder Value: A New Ideology for Corporate Governance,” Economy and Society, 29(1): 13–35.

Minsky, H. (1986) Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mitchell, M. and Mulherin, H. (1996) “The Impact of Industry Shocks on Takeover and Restructuring Activity,” Journal of Financial Economics: 193–229.

Orhangazi, O. (2008a) “Financialization and Capital Accumulation in the Nonfinancial Corporate Sector: A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation on the US Economy, 1973–2003,” Cambridge Journal of Economics, 32(6): 863–86.

——(2008b) Financialization and the US Economy. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Parenteau, R. (2005) “The Late 1990s US Bubble: Financialization in the Extreme,” in G. Epstein (ed.) Financialization and the World Economy, 111–48, Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Partnoy, F. (2003) Infectious Greed: How Deceit and Risk Corrupted the Financial Markets. New York: Times Books.

Plender, J. (2001) “Falling from Grace,” Financial Times, March 27, 20.

Pulliam, S., Smith, R. and Siconolfi, M. (2007) “US Investors Face an Age of Murky Pricing,” Wall Street Journal, October 12, A1.