11 Labor demand under strategic competition and the cyclical profit squeeze

Michele I. Naples1

The late-expansion profit squeeze analyzed by Boddy and Crotty (1974, 1975, 1976) derives in part from wage increases (Crotty and Rapping (1975)). As unemployment falls cyclically, wages rise due to workers’ improved bargaining power, eroding profits. At some point a sufficient profit squeeze induces companies to contract, and a downturn ensues. The subsequent recession restores workers’ economic insecurity, real wages slide, and renewed profitability leads to repeated expansion.

In the course of the expansion, labor demand is treated as relatively autonomous from the wage. Wages rise as the economy grows, yet output and employment continue to expand. This is inconsistent with models of perfect or imperfect competition which assume an inverse relationship between wages and employment due to diminishing returns.

This chapter suggests that the Boddy—Crotty theory of labor demand rests on a different approach, Strategic Competition (Naples (1998), Fazzari (Chapter 7)), which has Institutionalist and Post-Keynesian as well as Marxian roots. Strategic Competition is based on several non-Neoclassical assumptions. Firms face constant short-run returns to labor. Companies make strategic choices and satisfice in a world of uncertainty rather than following short-run profit-maximizing algorithms. They hire people for their potential; actual services elicited in the workplace are not specified in labor contracts.2

This chapter identifies flaws in existing theories of labor demand. It develops the Strategic Competition theory of wage determination in the absence of diminishing returns and short-run profit maximization. The conditions likely to generate no, positive, or negative feedbacks of higher wages on profitability are explored, then cyclically situated.

Constructing the demand for labor

Many heterodox analyses of labor demand incorporate Neoclassical assumptions. Efficiency-wage models of labor-effort extraction often assume both diminishing returns to labor and short-run profit maximization (Ash (2005)). Proposals for living wages defend against critics’ claims that higher wages will reduce labor demand, implicitly responding to Neoclassical labor-market analyses (Pollin and Luce (1998)). Yet, the dependence of jobs on wages stands on shaky ground.

Short-run returns to labor

In the Neoclassical view, diminishing returns to labor derive from the equipment and space becoming crowded with additional employees.3 Consequently marginal productive efficiency, i.e. output relative to labor-services rendered, declines as hiring expands.

This claim belies the empirical evidence since the 1930s that companies operate under short-run constant or increasing returns to labor (Blinder et al. (1998); Crotty (2001); citations in Johnston (1960); citations in Miller (2001)). This section elaborates on the empirical and analytical source of short-run constant or increasing returns.

Even if capital is fixed in the macroeconomic short run, there are several ways utilization can increase without crowding the workplace. Capital is often divisible in use: a store has many cash registers, a fast-food restaurant has several grills, and a large office has hundreds of desktop computers. And empty work-stations do not enhance workers’ productivity. Companies typically have on hand more plant and equipment than are fully utilized (Steindl (1976); Dean (1951)), precisely because planned excess capacity promotes responsiveness to a sudden burst of demand without causing unit-cost increases. Companies often consciously choose to set up several smallercapacity pieces of equipment rather than one large one to facilitate such flexibility (Andrews (1949)).

Let f represent the percent of an hour a piece of equipment is actually in use. Some machines are designed to be shared by several users in turn (e.g. photocopiers), and the extent of their utilization will be picked up by f. Some machines are used to provide direct services to customers, and will have a higher f when business is brisk, for any given employment level (e.g. cash registers); others have specialized uses and their f will depend on company demand patterns (e.g. sorting machines for large orders).

Capital can also be used by different employees at different times of day. By adding overtime, shifts and weekend work, the workplace’s hours of operation can vary daily, weekly or monthly. Define h as the share of potential hours (24/day, 168/week, 61,320/year) the company is operating; changes in h change the extent of capital utilization without necessarily changing the capital-labor ratio for each worker (Andrews (1949)).

Finally, the speed of the machine can sometimes be varied, independent of f or h (Dean (1951)).4 A stove’s temperature is raised to cook chickens faster during dinner hours at a fast-food or superstore take-out, or a hydroelectric dam is adjusted to generate more electricity when demand increases. Speed (s) is measured in proportion to the machine’s maximum potential speed.

Then capital utilization is a (row) vector μ, whose elements depend on these determinants:

μi = fi * hi * si(1)

which is a pure number. Productive efficiency (PE), i.e. output per labor-services rendered (LS), will be

PE = q/LS = f(μ K/LS)(2)

where capital stock K is a column vector of various kinds of equipment, plant, and inventories, and its product with μ determines the flow of physical capital services (Naples (1988)). Note that if μi and LS change proportionately, their ratio will be unchanged, and employment increases will not cause diminishing productivity.

While limited capital may be used more intensively if more workers are hired, it may also be used more intensively by the same workers if s increases. If one piece of capital equipment lies idle while another is in use, hourly f averages 50 percent. Doubling a company’s workforce and doubling f will keep PE constant. Even if frequency and speed were at workable maxima, it would be irrational for a company to crowd this worksite rather than expanding h by adding overtime, shift-work and weekend work,5 or by reopening a site idled by recession.

When companies choose to expand employment, neither PE nor APL6 should fall. Instead the business maintains the staffing ratio designed for its equipment (e.g. one person per desktop computer), and expands by varying capital utilization. Average and marginal productive efficiency, and ceteris paribus, productivity, are equal

APL = MPL(3)

and constant as the firm expands (Eichner (1987)).

The absence of diminishing returns makes sense of the profit-squeeze analysis of the expansion. If productivity is uniform, the marginal worker’s unit labor cost is the same as the inframarginal worker’s, so there is no productivity or cost constraint on increased hiring in economic booms without wage reductions.

Short-run profit maximization vs. satisficing and long-run goals

However, constant labor productivity raises questions about profit maximization, often used to close analytical economic models. In short-run labor-market models, imposing profit maximization means de facto assuming that companies maximize their profits in the short run, since these are the only profits under consideration.

Equation 3 implies that short-run profit maximization is not a viable business option.7 If marginal and average productivities are equal, then so are marginal and average variable unit costs. Short-run profit maximization would imply that price would be set equal to marginal cost, or in this case, that the wage would be set equal to the value of the marginal product of labor. But since the 1930s (Aslanbeigui and Naples (1997)), economists have concluded that when price is no greater than average variable cost, the business could not cover any of its fixed costs and would therefore shut down. By extension, wage setting in accordance with short-run profit maximization under constant labor productivity implies that workers would take home their entire average product (including what would otherwise cover overhead costs and profits), so all businesses would be at their shutdown points.

It is more reasonable that corporations with long time horizons, as well as small businesses that hope to survive the next downturn, will make strategic decisions instead of maximizing (Eichner (1987:360); Shapiro and Sawyer (2003:364)). They may choose to sacrifice short-run profits if doing so advances their long-run strategic goal, such as maintaining market share, introducing a new product, infiltrating a new market, etc. Many business Institutionalists suggest that companies choose to “satisfice” (Simon (1979)) or obtain “a reasonable profit” (Dean (1951:460)) rather than maximizing in a dynamic and changing environment. There is no perfect foresight, and information is costly. It would be irrational to maximize on the basis of what turn out to be faulty premises.

The offer wage

Forgoing the assumptions of short-run profit-maximization and diminishing returns in the theory of the demand for labor means that productivity offers inadequate guidance for company wage decisions, even at the micro level. Institutionalists argue that a company’s wage offer for each job is determined by administrative criteria, such as managerial or fiduciary responsibilities, and that potential productivity is embodied in the job rather than the person (Thurow (1998)). Certain key wages serve as reference for other wages relying on similar skills and technology in or across industries. Occupational wages vary by firm in accordance with its particular market niche and management culture, including with respect to women, minorities and immigrants.

In the heterodox tradition, the chronic presence of unemployed or under-employed competitors gives all employers significant labor-market power vis-à-vis workers in setting wages (Boddy and Crotty (1975)). Management consultants like Dean (1951) see all companies as having some degree of market power in their local output market, if only by virtue of location; by extension, they would in their local labor market as well.

If different companies have different degrees of labor-market power, they may offer different wages. Case studies of occupations and locales have observed that despite competitive pressures, wages tended to fall in a “range of indeterminacy” rather than conforming to a uniform market wage (Lester (1952); Dunlop (1998)).

Wage determination has intricacies not captured by simple models, as the compensation-management literature attests (Henderson (2005)). Nevertheless, this discussion of labor-market power suggests an expanded interpretation of the Post-Keynesian mark-up and an avenue for constructing the Strategic Competition theory of the wage offer.

In the standard formulation, prices are interpreted as marked up on unit labor costs (ULC) and unit materials and energy costs (UMEC) (Shapiro and Sawyer (2003)):

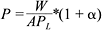

P = (ULC + UMEC)*(1 + m)(4)

where the mark-up, m, covers overhead and profits. We can replace ULC with W/APL, and rewrite this equation as

(5)

(5)for an expanded mark-up, α, that covers non-labor variable costs as well, following Goldstein (1999). Traditionally the mark-up is understood to reflect the extent of overhead, the company’s profit-rate target, and its degree of output-market power (Eichner (1987:375–81)).

It is illustrative to reframe this equation with wages as the dependent variable:

(6)

(6)For strategically competitive concerns, the wage depends on labor productivity and output price as mediated by the mark-up on unit labor costs, α. The above Institutionalist labor discussion suggests that a host of industry and companyspecific factors, including racial and gender criteria, may also be captured by α. Then α is a measure of our ignorance, a crucial factor in setting wages that cannot be known without applied industry-based research, namely, a historical, Institutionalist approach.

The effect of wages on labor demand under strategic competition: three cases

It is nevertheless possible to explore possible relationships between the wage and employment demanded analytically. Three cases will be considered: independence, positive relationship and negative relationship. It will later be argued that each holds sway under particular cyclical conditions.

Case 1 Wage-neutral labor demand: Keynesian—Cross

Constant returns to labor imply constant average variable costs; therefore average total costs decline steadily as employment increases. Under Strategic Competition, there is no rising-cost constraint on expanding employment in response to higher demand as there would be in Neoclassical theory.

Then labor-hours hired depends not on the wage, but on the demand for the firm’s product (qD), given worker productivity,

(7)

(7)Changes in company sales will shift labor demand without the mediation of price (namely, the wage rate), and company demand for labor is vertical.

In this view, output demand affects labor demand through a quantity-quantity mechanism: a higher quantity of sales leads to a higher level of employment. This microfoundation arguably underpins the Keynesian—Cross Aggregate Expenditure model. Aggregating labor demand across companies and industries, any shift in aggregate expenditure (AE) calls forth an equal change in GDP and a proportionate change in employment without reference to the price level. So aggregate employment demanded (ND) is

(8)

(8)In Boddy and Crotty’s (1975) and Goldstein’s (1996) story of economic recovery businesses expand in response to increases in aggregate expenditure. There is no appeal to wage changes in these characterizations of economic recovery, employment expands in direct response to greater effective demand for output, which is exogenous to the wage—employment relationship.

Case 2 Positive wage—employment relationship: wage-induced consumption

Some Radicals argue for a positive feedback of increased wages on consumption and therefore employment demand (Sherman (1997)). Followers of Kalecki (1971:28), such as Lavoie (1998), expect wage increases to affect aggregate expenditure directly, causing employment increases. Keynes (1964) too foresaw a negative impact on consumer spending from lowering wages. Early advocates of union rights and minimum-wage laws shared this perspective (Kaufman (1993)), expecting wage-stabilization/wage increases to stabilize/expand employment.

This macro argument would not change Equation 7. Individual companies would hire in response to their sales, which are not likely to change appreciably by paying their workers more. But it suggests a fallacy of composition in extrapolating directly to Equation 8, if in the aggregate workers do purchase more when wages rise, pulling employment up.

If higher wages raise consumption and therefore employment offered, the macroeconomic demand for labor would be upward sloping, despite the vertical microeconomic demand. This is not a trajectory of possible equilibrium points, but a causal model whereby employment offered depends on the wage as mediated by the consumption function and aggregate expenditure. Unlike the Keyne-sian—Cross model, where consumption depends on GDP, in this Kaleckian formulation, wages drive consumption and therefore employment.

Case 3 Negative wage—employment relationship: cost-induced profit squeeze

Boddy and Crotty (1975) attribute the late-expansion profit squeeze in part to rising wages. Goldstein (1996) has emphasized that this cyclical argument holds even when real wages are trending downward, as in recent years. The increased unit labor costs are not fully passed on in higher prices, and profitability declines. Rising costs eventually push workers out of jobs via their deleterious effect on profits, even if productivity is constant.

Equation 7, the company’s demand for labor, is replaced with a more complex causal model:

(9)

(9)for some measure of company financial health, F. This measure is itself a composite of profit performance in the recent past, debt and interest rates, as well as current profitability. Beyond some threshold level of F, LD responds directly to lower F even if the first term is rising. Equation 7 becomes a special case of Equation 7', which begs the question of when g2 ≠ 0.

Some have suggested that companies can pass on cost increases, bypassing any cyclical profit squeeze (Epstein (1991)). Nevertheless extensive empirical research confirms procyclical real wages (see citations in Goldstein (1996:88); Lavoie (1998:109)). This suggests that administered pricing prevails rather than Neoclassical marginal-cost pricing. Under the former, it is industry’s practice “to change prices infrequently and to attempt to … refrain from major price increases in periods of rising demand” (Dean (1951:457)). This avoids losing customers to substitute goods, preserves client loyalty and prevents a longer-run loss in sales (Shapiro and Sawyer (2003); Lee (1998:212–14)). The press of competition, e.g. from imports (Goldstein (1996:84, 88)), or simply the uneven experience or knowledge of others’ wage increases constrains company markups and permits real wages to rise.

The late-expansion vulnerability of profits rests on the particular form competition takes in expansions. Competitive pressures on companies to cut costs are mitigated by the benefit of the growing economy for profits (Goldstein (2006)). Dean (1951) argues that the focus of competition in the boom is to expand markets and market share; it is in the contraction as the pie shrinks that cost-cutting becomes crucial. Those companies that do not engage in product innovation and create new markets for themselves in expansions will not survive recessions any more than successful expanders who do not cut costs in downturns (Crotty (2000)). This suggests that rather than conceiving of competition as attenuating in the late-expansion, the unique shape competition takes is what creates the potential for the late-expansion profit squeeze.

In Case 3, wage increases impair profitability. Some level of F serves as the tipping point beyond which further wage increases lead to layoffs (Equation 7).8

The context for each macroeconomic wage—employment case

The macroeconomic demand for labor depends on factors that vary cyclically. The cyclical sensitivity of consumer spending and of profits to wage changes will be taken up in turn.

The sensitivity of consumer spending to wage changes

For several reasons, current wage changes may have little impact on aggregate expenditure. Until consumers know that their income change is permanent, they are not likely to spend any extra money earned (Goldstein (1999:79)). Workers in cyclically sensitive industries, such as construction and manufacturing, are familiar with the pattern of tight labor markets and rising wages in the boom, and scarce jobs in the recession, and are unlikely to treat cyclical wage increases as if they were somehow on a new higher-income trajectory.

Workers are also uncertain about inflation. A nominal wage increase may or may not translate into higher real purchasing power. In recent decades inflation has tended to erode real household income. Even union cost-of-living clauses are only partial adjustments. Uncertainty about inflation will reduce any tendency to spend wage gains.

This suggests that a feedback from wage increases to higher aggregate expenditures is not automatic but contingent, and more likely if perceived as permanent and real. We cannot draw a positively sloped macroeconomic demand for labor; it is more accurate to treat the aggregate demand for labor as vertical and AE as exogenous.

The effect on profits of wage gains

Assume that, despite these caveats, sustained wage increases do at some point promote higher consumer spending as Kaleckians and some Post-Keynesians believe. Such an expansion of sales will tend to raise profits, ceteris paribus. Unlike Neoclassical models, where companies only produce until marginal cost equals marginal benefit and then stop expanding, Post-Keynesians argue it is in companies’ interest to produce as much as they can sell (Eichner (1987)). Abstracting from changes in unit labor costs, as demand expands companies gain higher profits from two sources: high unit profits as overhead costs are spread over more items so average total costs decline, and higher total profits from increased sales.

To clarify, the profit rate (∏) may be expressed in terms of the profit margin, Πm:

(10)

(10)where OLC represents overhead labor costs and PK is a row vector of historic capital-good prices. If current labor and material costs are small relative to fixedcapital and overhead-labor costs, then from Equation 5 and a scalar measure of aggregate capacity utilization, υ = q/qp (potential output),

(11)

(11)The denominator represents the capital intensity of production, the extent of employee surveillance, and of overhead labor. The numerator on the right differentiates the positive impact of increased sales on the profit rate via υ from the negative impact of a lower profit margin from rising labor costs.

It is tempting to conclude that the issue is whether increased demand (through rising υ) outweighs rising costs (through falling Πm). However, high demand does not directly translate to higher capacity utilization, which also depends on its denominator, the extent of capacity. Given the procyclical behavior of investment, allowing for some time between initial investment spending in the early expansion and final plant opening, capital grows in the latter portion of the economic expansion.9 But this implies that the same proportionate increase in AE during the late expansion will have less impact on υ than it would have had earlier, because simultaneously the denominator of υ is expanding due to the expanded capital stock. Since investment lags the cycle, this expanded-capacity effect will likely extend into the onset of recession, reducing υ even faster than AE falls, and exacerbating the crisis phase. It means that the likelihood that a profit squeeze from rising unit labor costs would dominate any inducedconsumption effects is greatest in the very phase of the cycle when induced consumption is most likely due to sustained wage increases—the late expansion. Case 2 is not very probable.

Summary: the cyclical pattern for the wage—employment relationship

The effect of wage changes on the macroeconomic demand for labor depends on the phase of the business cycle. In the early expansion, Case 1 dominates, as companies hire more workers in response to higher sales without attending to wages. Unemployment is still high and fear of job loss prevents workers from pressing for higher wages. At the same time, constant returns and administered prices means companies respond to higher aggregate expenditure by increased labor demand, without any prior wage change.

As the expansion proceeds, economic insecurity is mitigated by employment growth. Workers as individuals and as groups have an improved bargaining position to negotiate higher wages. This pattern is consistent with either Case 1 or Case 2, since these wage increases do not hurt employment demand—employment responds directly to AE. Whether wage increases have also promoted higher consumption, capital utilization and therefore profitability is an empirical question. It depends on both the consumption—wage link, and the timing of the opening and operation of new facilities and equipment. In this phase, the expansion of effective demand plus any increased consumption spillovers from higher wages dominate profit-squeeze effects.

The late expansion (from peak profitability to the cycle peak—Boddy and Crotty (1975)) is by definition the period where the profit-squeeze overwhelms any benefits from expanding demand. The analysis presented here shows that part of the reason for this change is the very acceleration of spending in the earlier period: new capital has been brought into production, and as capacity expands, utilization drops. While the economy continues to expand, labor demand fits into Case 1 or 2). Once companies reach their tipping point, the demand for labor shifts back, not because of declining AE, but worsening financial circumstances. This is initially Case 3, but as F worsens and AE falls, we return to Case 1 in the downward direction.

Conclusion

This chapter has illustrated the Strategic Competition theory of employment demand under the cyclical profit squeeze. Constant returns to labor prevail, given companies’ practice of varying utilization by changing hours of operation, machine speed and frequency of use of machines in lieu of crowding the workplace. Short-run profit-maximization is not a viable assumption under constant returns, and strategic companies will satisfice and pursue long-run profit strategies rather than maximizing short-run profits. Together these motivated the relative autonomy of wage-setting from company employment decisions, driven by expected sales. Wages are not determinate a priori but are historically contingent, requiring empirical research to close the labor-market model.

The dependence of the wage—employment relationship on cyclical factors provides the microeconomic foundation for the late-expansion profit-squeeze. Even allowing for the Kaleckian case that a higher wage may lead to higher consumption (an empirical question), profits will nevertheless be squeezed once new capacity begins operation later in the expansion. The three cases outlined above expose the labor-market underpinnings implicit in Boddy and Crotty’s (1975) macro story.

Notes

1 Thanks especially to Nahid Aslanbeigui, Jim Crotty, Jon Goldstein, Teresa Ghilarducci, Margaret Andrews, Fred Lee, Al Campbell, Gil Skillman, my students, and Rebellious Macroeconomics conference participants for helpful feedback.

2 This assumption underpins the late-expansion productivity slowdown (Naples (1998)).

3 Joan Robinson (1953) observed that adjusting output by adding more workers to equipment requires redesigning the production process with every hire.

4 Dean’s Managerial Economics rewrote graduate MBA economics from an Institutionalist perspective; it dominated the postwar textbook market through the 1950s and 1960s.

5 Whether night-time or weekend work pays a premium depends on the industry and locale. Some sectors require weekend work without premium pay in alternating shifts (e.g. nursing homes, public libraries). In others, night work is less desirable entry-level work while daytime slots are prized and pay more.

6 APL = PE*LP*LI, where LP is labor performance per effort exerted, and LI is labor intensity, or hourly effort (Naples (1998)).

7 Crotty (2001) makes a similar argument for core industries with excess capacity. In companies with significant scale economies, marginal costs lie far below average total costs and rise slowly if at all, which also obviates marginal-cost pricing.

8 Goldstein (1996:68) observed the seeming delay of the profit-squeeze in recent expansions. Alternatively, the profit peak may have more rapidly led to a downturn due to greater financial fragility with high debt overhangs, or proactive Fed intervention.

9 Crotty and Rapping (1975:796) suggested that late-expansion investment in labor-saving techniques will not come online until early in the next expansion. In conversation at the conference, Ray Boddy reported that metal-working supervisors often let new equipment sit idle rather than miss production goals, given a likely learning curve and needed adjustments. Keynes (1964), however, saw the advent of additional capital assets of a particular type in the boom as explaining downward sloping marginal efficiency of capital. Arguably new office buildings or equipment (desktop computers, forklifts) will take less time to be put into operation than new manufacturing processes; an office complex can be built, furnished and opened in one year. Sherman’s (1997) view that late-expansion stagnant growth of capacity utilization reflected limited demand did not perceive this likely supply-side impact.

References

Andrews, P. W. S. (1949) Manufacturing Business. London: Macmillan.

Ash, M. (2005) “Disciplinary Unemployment as a Public Good, or the Importance of the Committee to Manage the Common Affairs of the Whole Bourgeoisie,” Review of Radical Political Economics, 37(4): 471–5.

Aslanbeigui, N. and Naples, M. I. (1997) “Scissors or Horizon: Neoclassical Debates about Returns to Scale, Costs, and Long-Run Supply 1926–1942,” Southern Economic Journal, 64(2): 517–30.

Blinder, A. S., Canetti, E. R. D., Lebow, D. E. and Rudd, J. B. (1998) Asking About Prices; A New Approach to Understanding Price Stickiness. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Boddy, R. and Crotty, J. R. (1974) “Class Conflict, Keynesian Policies, and the Business Cycle,” Monthly Review, 26(5): 1–17.

——(1975) “Class Conflict and Macro-Policy: The Political Business Cycle,” Review of Radical Political Economics, 7(1): 1–19.

——(1976) “Wages, Prices and the Profit Squeeze,” Review of Radical Political Economics, 8(2): 63–7.

Crotty, J. R. (2000) “Structural Contradictions of the Global Neoliberal Regime,” Review of Radical Political Economics (Summer).

——(2001) “Core industries, Coercive Competition and the Structural Contradictions of Global Neo-liberalism,” Working Paper, University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Crotty, J. R and Rapping, L. A. (1975) “The 1975 Report of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors: A Radical Critique,” American Economic Review, 65(5): 791–811.

Dean, J. (1951) Managerial Economics. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Dunlop, J. T. (1998) “Industrial Relations Theory,” Advances in Industrial and Labor Relations, 8: 15–24.

Eichner, A. S. (1987) The Macrodynamics of Advanced Market Economies. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe.

Epstein, G. (1991) “Profit Squeeze, Rentier Squeeze and Macroeconomic Policy Under Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rates,” Economies et Sociétés, 25(111 & 12): 219–57.

Goldstein, Jonathan P. (1996) “The Empirical Relevance of the Cyclical Profit Squeeze: A Reassertion,” Review of Radical Political Economics, 28(4).

——(1999) “The Simple Analytics and Empirics of the Cyclical Profit Squeeze and Cyclical Underconsumption Theories: Clearing the Air,” Review of Radical Political Economics (Spring).

——(2006) “Marxian Microfoundations: Contribution or Detour?” Review of Radical Political Economics, 38(4): 569–94.

Henderson, R. I. (2005) Compensation Management in a Knowledge-Based World. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Johnston, J. (1960) Statistical Cost Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kalecki, M. (1971) Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kaufman, B. E. (1993) The Origins and Evolution of the Field of Industrial Relations in the United States. Ithaca: ILR Press.

Keynes, J. M. (1964) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World.

Lavoie, M. (1998) “Simple Comparative Statics of Class Conflict in Kaleckian and Marxist Short-run Models,” Review of Radical Political Economics, 39(4): 101–13.

Lee, F. S. (1998) Post Keynesian Price Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lester, R. A. (1952) “A Range Theory of Wage Differentials,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 5(4): 483–500.

Miller, R. A. (2001) “Firms’ Cost Functions: A Reconstruction,” Review of Industrial Organization, 18(2): 183–200.

Naples, M. I. (1988) “Industrial Conflict, the Quality of Worklife and the Productivity Slowdown in US Manufacturing,” Eastern Economic Journal, 14(2): 157–66.

——(1998) “Technical and Social Determinants of Productivity Growth in Bituminous Coal Mining, 1955–1980,” Eastern Economic Journal, 24(3): 325–42.

Pollin, R. and Luce, S. (1998) The Living Wage: Building a Fair Economy. New York: New Press.

Robinson, J. (1953–4) “The Production Function and the Theory of Capital,” The Review of Economic Studies, 21(2): 81–106.

Shapiro, N. and Sawyer, M. (2003) “Post-Keynesian Price Theory,” Journal of Post-Keynesian Economics, 25(3): 355–65.

Sherman, H. (1997) “Theories of Cyclical Profit Squeeze; A Comment on Jonathan Goldstein, ‘The Empirical Relevance of the Cyclical Profit Squeeze: A Reassertion’,” Review of Radical Political Economics, 29(1).

Simon, H. (1979) “Rational Decision Making in Business Organizations,” American Economic Review, 69(4): 493–513.

Steindl, J. (1976) Maturity and Stagnation in American Capitalism. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Thurow, L. C. (1998) “Wage Dispersion: Who Done It?” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 21(1): 25–37.